By Tim Miller

On October 28, ad 312, a Roman emperor was drowning. The sight must have amazed his soldiers. All summer Rome had been filled with rumors of the western emperor, Constantine, and the ease with which he and his army had crossed the Alps and, once on Italian soil, strung together a handful of victories in the north. The average soldier in Rome, whose allegiance was to his emperor, Maxentius, must have seen what was coming and wondered how the well-trained, veteran army would fare against them.

Their armies met about two hours northwest of Rome at the remains of the Milvian Bridge over the Tiber River, and in less than an hour the worst fears of Maxentius’s troops were realized. The superstitious among them may have thought Maxentius knew the outcome before going in. Having ordered the destruction of the Milvian Bridge to halt Constantine’s advance, Maxentius had built a temporary bridge of boats over the swift-flowing Tiber and lined his men with their backs to it, making anything but victory a choice between drowning and being butchered. Suddenly, the bridge of boats buckled under the weight of all those retreating to it. Fleeing men weighed down by armor and weapons, and those unable to release themselves from their frantic horses, drowned in the Tiber’s swirling waters.

Those lucky enough to have reached the other side before the bridge gave way would have seen Emperor Maxentius fall just as quickly. Indeed, he fell just like any other man. The survivors watched in horror as their leader, supposedly of some greater importance than the rest, drowned just the same as any man.

For all this, though, contemporary accounts try to maintain that distance between emperor and solider by saying that the Tiber, personified as the god Tibernius, actually swallowed and devoured Maxentius in his own personal whirlpool. Although the logistics of this seem less than probable and reek more than anything of the victor’s propaganda, there is no doubting that the image is born from the real terror and amazement of an all-powerful emperor succumbing to the waves.

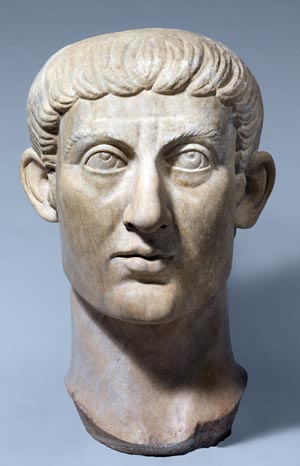

“Byzantine” has not become a byword over the centuries for scheming and intricacy by accident, as only the briefest summary of its early years can attest. The years ad 235 to ad 284, during which more than 20 men were proclaimed emperor, was a period of astonishing instability and near collapse in the Roman Empire. Things changed when Diocletian, a cavalry officer from Dalmatia, was proclaimed by the western and eastern armies in 284. A year later he appointed a co-emperor in Maximian, also plucked from the military, and together they adopted the titles of gods and heroes. Diocletian took the title of the distant and bureaucratic Jupiter, and Maximian chose the name of Hercules, who was the muscle of the empire. Perhaps unintentionally, they were taking a page from their greatest enemies, the Persians, who had long found centralized authority easier to maintain by equating religious and political power. This created an implicit demand for a form of religious uniformity unknown until then in the Roman Empire.

During his reign Diocletian also divided the empire up into provinces of smaller sizes, all to impose a visible imperial presence on as much of the subject population as he could. This required the creation of a massive bureaucracy he hoped would subdue the risks inherent in governing such a large empire. While Diocletian had obviously benefited from the influence of armies, the presence of high government officials in the daily lives of the citizens also was meant to discourage usurpers and keep the military from proclaiming another emperor.

To fix that other inherent problem of kingship; namely, that of succession, in 293 the Tetrarchy was created. Under this arrangement, Diocletian and Maximian (who used the title of Augustus) both appointed someone beneath them in the slightly lesser position of caesar, and the Roman Empire was now divided into four zones of authority. Maximian oversaw the areas of Italy north through the Alps and to the Rhine, south and west to Spain, and the North African coast to Egypt. Diocletian administered Egypt, Israel, Syria, and Turkey. Galerius governed the areas south of the Danube River, Greece, and the Balkans (including Diocletian’s old home of Dalmatia). Constantius, the father of Constantine, was responsible for northern Spain, France, and Britain south of Hadrian’s Wall.

Only after 298, which saw the defeat of the British and Persians and the subduing of a rebellion in Egypt, did Christianity come under suspicion. At that time it was a religion tolerated by the empire, whose adherents were regulars in the royal courts and the military. Diocletian and Galerius were in Antioch in or around 299 when a sacrificial ritual of divination produced unreadable results, the Christians of the court were blamed because they refused to participate, and the two men quickly set about to enforce the basics of pagan piety. They ordered that regardless of the god, everyone must sacrifice.

The swiftness of this move highlights how much of the pre-Diocletian volatility still remained. The return to pagan sacrifice produced immense religious anxiety and conservatism. The demand for religious uniformity spread to military personnel, too. By 303 this shift produced the Great Persecution in the Eastern Roman Empire, which manifested itself in the destruction of Christian churches, the burning of holy books, the outlawing of their even meeting in public, and in torture and execution.

Those who survived but still refused to participate in pagan rites were stripped of their rank, and there was an attempt to imprison all clergy. And like many a fundamentalist before and since, Galerius fell into the persecutions with a savage joy and fervor that went beyond any mere political advantages they might yield or religious devotion they might reflect.

By this time Constantine, whose birth year varies in the sources, was in his mid-30s. He had spent his formative years receiving the best education possible in the crowded court of Diocletian, but at the same time had likely been held there, if not as a prisoner, certainly as insurance against his father revolting. In the years leading up to the Great Persecution, Constantine saw Babylon and Memphis, had fought the Persians in Syria and Mesopotamia under both Diocletian and Galerius, and elsewhere campaigned against the barbarians on the Danube. There is no indication that he either protested against, or took part in, the persecutions, but historian Eusebius does say he was present at the court of Diocletian when so-called edicts of carnage were promulgated, and it is possible that he witnessed the Christians’ steadfastness even unto death.

Soon afterward, in 305, the Tetrarchy was put to its first and only test. Despite Diocletian’s careful hopes for stability, corruption found its way. When Diocletian fell ill in 305, Galerius encouraged both Diocletian and Maximian to abdicate, which the latter did only reluctantly. As a result, Constantius and Galerius both became Augusti. But instead of Constantine being chosen as caesar under his father in the west, the two caesars actually selected both had family ties to Galerius. Flavius Severus was a friend in the army, and Maximinus was his nephew. Diocletian subsequently retired to a vast palatial complex in Dalmatia.

Suddenly stripped of the title that many thought belonged to him, Constantine found himself a prisoner of Galerius. Folk tales arose in which Galerius made unending attempts on Constantine’s life, but the amusement derived from some notion of Constantine always getting his way belies the real danger to his life. In the summer of 305, his father asked that Constantine be sent to help fight the empire’s wars in Britain, and Galerius agreed only after a night of heavy drinking. By the time he emerged from his stupor the next morning, Constantine was long gone. He met his father in Gaul, and the two crossed the Channel to Britain. They spent the next many months campaigning north of Hadrian’s Wall, warring against the Picts. On July 25, 306, Constantius succumbed to illness and died.

Before passing away, and without any authority to do so, he assented to his son succeeding him as Augustus, and his father’s army did the same. Thus, Constantine was first acclaimed emperor in a city rarely associated with Byzantine history. This event occurred not amid wars in North Africa, the Middle East, or Italy, or in the cauldron the Balkans has always been, but in Eboracum (modern-day York).

Word was immediately sent to Galerius, with Constantine disingenuously claiming his father’s title had been foisted upon him by the army, and that he had never sought it. Knowing that to refuse Constantine outright would result in civil war, Galerius placated him by offering him the title of caesar only, with Severus promoted to Augustus. Since it bought him time, Constantine agreed, and he spent the next year or so cementing his control of Britain and then crossed the Channel to deal with the unruly Franks, who had risen up at the news of his father’s death. Along the way, he also continued his father’s more lenient treatment of Christians (the edicts of persecution enacted so enthusiastically in the east were hardly followed at all in the west), and in his new position Constantine made contact with many Christians, among them the bishops of Cordoba, Trier, and Cologne.

Constantine spent the next six years in the west, solidifying his control there, while claimants for the eastern throne exhausted themselves in civil war. Maxentius, the son of Maximian, who had also been overlooked for the title of caesar upon the abdications of 305, saw how easily Constantine had forced a title on himself and so was proclaimed emperor by the Praetorian Guard in Rome. In a few years, he took control of Italy and North Africa, defeating attempts by Galerius and his caesar to take back both. In 311, he seized the provinces in Asia Minor upon Galerius’s death.

Muddied into all of this were his successful attempts at calling his father out of retirement, only for them to eventually oppose one another. And indeed the aging Maximian, before his death, fled to Constantine before it was all over, dying in the west. When Maxentius declared war on him, he did so in part under claims that Constantine had killed his father, which is unlikely. What is clear is that Diocletian’s hopes for easy succession had not lasted beyond a breath. Whether Constantine invaded Italy as an aggressor or in response to Maxentius’s declaration of war is irrelevant. Both were technically usurpers; at that point, they were finally at war with each other.

Constantine entered Italy in the spring of 312. Accounts of the events that followed are derived from two church historians and theologians, Eusebius and Lacantius, and two orators, one named Nazarius and one simply known as the anonymous orator. All but the last of these historians were Christian, and all of them witnessed the Great Persecution. They wrote their accounts of Constantine when Christianity was still a new and potentially perilous presence as a favored religion in the empire. The orators also were the authors of publically performed panegyrics, or speeches of praise, and at least one of them likely performed before Constantine himself. To the cynic, all of these circumstances might throw their accounts into suspicion, but a reliable narrative can be found.

Before the campaign began, Constantine’s soothsayers oversaw a divinatory sacrifice that clearly made any military action in Italy ill omened, but by this point Constantine was beyond confident and ignored their warnings. He was given a boost thanks to an event that probably dates from the months before he crossed the Alps with his army. Collating all the accounts, we can say that, fervently pious toward the religious cult of the Unconquered Sun (Sol Invictus, one of the most popular deities in the Roman army), Constantine one day at noon was in prayer, with the sun at its highest point in the sky, when “he saw with his own eyes, up in the sky and resting over the sun, a cross-shaped trophy formed from light, and a text attached to it which said, ‘By this, conquer.’”

The company of soldiers with him also witnessed the event. But as if the author of this vision was aware of its vagueness, that night Christ himself appeared in a dream and was more specific, saying that Constantine and his men should fight beneath the symbol of the Chi (X) Rho (P), a monogram of the first two letters in the Greek word for Christ. A standard, or labarum, topped by the Chi Rho was then constructed and placed before the advancing army, and Constantine also told his soldiers to paint it on their shields.

Yet combining the accounts, as later streamlined tradition inevitably does, results in a nonexistent clarity over the event. One account places the vision on the day before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, and another leaves out the night dream and betrays neither a Christian or pagan slant, while the earliest account of the Italian campaign mentions no vision or dream at all, but does assume Constantine was divinely guided: “You must share some secret with that divine mind, Constantine, which has delegated care of us to lesser gods.” Perhaps counterintuitively, the inconsistencies in the accounts may speak to the genuinely strange nature of the experience, which was remembered, retold, and reinterpreted throughout Constantine’s life.

The standard of Sol Invictus was not left behind in light of this new one; rather, they were both taken together, and Constantine’s allegiance to Sol is still reflected years later. Neither the divine visions of emperors or generals nor the painting of apotropaic symbols on shields or armor was anything new, nor did Christianity have a monopoly on using cross-shaped signs for good fortune or protection. The man who only a few years earlier had had a vision of the sun god Apollo, and who said Sol had carried his father off after death, and who no doubt knew of the Christians in his train who associated Christ and his resurrection with the risen sun, could not miss the connections or refuse the support of whatever gods he could get. His self-assurance must have been overwhelming as he crossed a southwestern portion of the Alps, taking only a quarter of his army with him and leaving the rest behind in Gaul. He emerged in northern Italy with around 40,000 men who would not be satisfied until they reached Rome.

The first town they came to was Segusio, which closed its gates to the army and apparently did not believe that Constantine was really among them. “For who would believe,” asks the anonymous orator, “that an Emperor with an army had flown so quickly from the Rhine to the Alps?” When he offered to forget their obstinacy if they would only open the town to him, they still refused, and so Constantine ordered a siege not with palisades or battering rams but quite simply by setting fire to the closed gates. Segusio quickly capitulated even as the fire spread, and Constantine went from the town’s destroyer to its savior, ordering his men not to pillage or rape but also to put out the flames, which took more time and effort than the attempted siege. “Thus at his departure he made the city so fond of him that it was not fear of his victory but admiration for his gentleness which reconciled it to total allegiance,” wrote Nazarius.

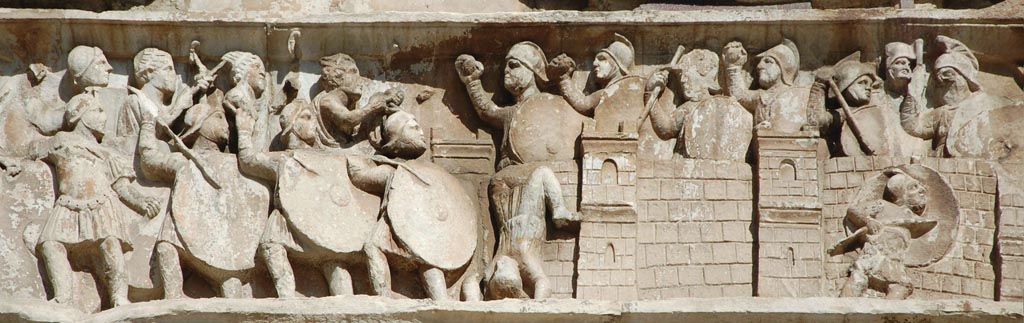

Constantine continued 40 miles to the east to Turin, one of the many cities in northern Italy where Maxentius had placed pieces of his vast army. Originally stationed there in case Constantine’s only ally in the east, Licinius, attempted to enter Italy from Dalmatia, they must have been surprised to face an enemy arriving from the west. Uniquely, the Maxentian force (their leader is not named) was led by a huge line of mailed cavalry.

“How terrible,” Nazarius wrote, “horses and men alike enclosed in a covering of iron!” These were the clibinarii, or “oven men,” based on Persian riders similarly encased; although, for these men, their enclosure became their doom. Constantine’s men, outnumbered and impressed by the spectacle, are said to have taken confidence in the challenge: the victory at Segusio had been too easy and not worth bragging about, while these men hiding head to toe in armor were an enemy that Constantine wanted badly to defeat. They rode right into Constantine’s trap. By extending and thinning out his lines, he invited a charge which his men immediately encircled and swallowed in a classic envelopment.

They were beaten to death, with clubs, maces, and axes all battering down on their armor and helmets, and on the exposed areas of their quickly collapsing horses. Thousands of death-rattled horses threw their mail-wrapped riders to the ground. Those who attempted to flee back to Turin found the gates closed to them, and the slaughter continued there until their piled corpses blocked the gate entirely. “What else could you have expected for yourself, unhappy soldier, when you had devoted yourself to a loathsome monster?” wrote the anonymous orator.

It was in this way that the people of Turin declared themselves for Constantine and saved the city the terror of a siege. Many other cities in northern Italy, but by no means all, followed suit in welcoming him, and they sent both embassies and supplies. He received a grand welcome 100 miles farther east in Milan, where he and the army rested for a month or more.

Before he could turn south for Rome, however, and after a victorious cavalry skirmish in Brescia, Constantine had to face what the anonymous orator calls “that miserable town, Verona.” It was held by an army headed by the praetorian prefect Ruricius Pompeianus, one of the mainstays among Maxentius’s generals, and a man characterized as being as vicious as his soldiers were mad and filled with greed. Verona was also protected by its location in a bend of the River Adige, but knowing this, Constantine merely sent a contingent of his army north (perhaps as far as a bottom lip of the Alps that dipped near the city), to cross the Adige at a calmer point. With Constantine’s forces suddenly approaching the city, the bend in the Adige became the barrier at Pompeianus’s back, and the force he sent out to face them was easily defeated. With the entirety of Constantine’s army now across, Pompeianus led a force that was also defeated, only to retreat east of the city to receive the lucky arrival of reinforcements.

All later accounts of the Battle of Verona downplay the danger of this moment, but it was palpable. Essentially forced to fight on two fronts (those besieging the city and those awaiting further battle with Pompeianus), and at that point with the Adige at his back, Constantine’s army was spread thinner without any additional aid. Well aware of the superiority of his numbers, Pompeianus was eager to get on with the fight, but made the mistake of continuing it immediately. Rather than giving the recently arrived men an evening to rest, he rushed out to face Constantine who, to avoid his own trap at Turin, spread his lines out even further to keep Pompeianus’s wings from closing around him. By then it was nearing nightfall, and Constantine himself entered the fray, leading the cavalry charge. The anonymous orator equally praises and condemns Constantine’s courage in putting himself and his reign in danger by entering battle so conspicuously. The orator concludes that this must reflect something like his invincibility and divine approval: “You were carried away entirely by your impulse, like a river in flood carrying along trees broken off at their roots and rocks torn away from their foundations,” he wrote. “What do you have to do, emperor, with the fate of inferior beings?”

Comparisons to those rulers from Persia to Rome who preferred to watch battles from a distance are exploded by Constantine’s youth and action, courage, and vigor. This is no better illustrated than by his and his army literally fighting in the dark, leaving so much to Fortune, and even stealing from their victims the usual honor of knowing who cut them down, since a dying moment would apparently be assuaged if you knew someone famous had done it. Indeed, Pompeianus’ force was defeated, and he was killed in the battle. “Death subdued his fury,” wrote Nazarius.

The enemy soldiers who remained—condemned by the orator as having essentially abandoned their Roman identity when they took up arms against Constantine—were put in shackles made from their own melted-down weapons. When Verona finally acquiesced to Constantine, so did other towns in northern Italy, such as Aquileia, Ravenna, and Mutina.

Although some smaller cities may have capitulated after a siege, Constantine’s road was essentially open south to Rome. By then it was late summer, and Constantine’s army took its time moving south; the evidence of battle-wounded soldiers who died and were memorialized along the way provide evidence of his movements.

Maxentius tried to suppress news of Constantine’s victories among the Roman elite and the public, but such news could not help but get out. At the games, which took place in the coliseum, jeers of Constantine’s invincibility surrounded him. What he had taken as an expression of his strength and position, namely that others were fighting in the north instead of him, clearly became a sign of weakness. Constantine milked this growing sense of Maxentius’s softness as long as he could, not reaching Rome and not being met by another army until late October.

The ancient sources fill these months of Maxentius’s time with every excess and crime of which a supposedly idle tyrant might be accused, including lechery, theft, and even murder. He is also given the physical description of a tyrant, universal then and now, who is deformed in some conspicuous manner. Moreover, while Constantine is granted the counsel of divine powers, Maxentius is said to have been guided by the superstitious mischief found in unconventional magic far different from what might anachronistically be called orthodox paganism. Some of the practices he was accused of, such as prophesying from the entrails of slaughtered lions or newborn babies torn from their mother’s wombs, or in attempts to conjure demons, would have been beyond the pale for anyone at the time.

As October neared, however, the real Maxentius remained, and still remains, a mystery. That anyone held power during that time, and had done so for six years, must speak to some level of charisma, some competency in leadership, and he must have inspired confidence beyond the desperation of armies needing to acclaim someone. All of the accusations heaped upon him only surfaced after Constantine’s string of victories, and indeed, had their one and only battle turned out differently, everything from Constantine’s vision to his wars in the north would likely have been turned into the worst superstition and atrocity.

In the lead up to battle, Maxentius consulted the oracles and received one of those mainstays of ancient prophecy. He was told that “an enemy of Rome would die.” While other ancient recipients of such prophecies seem to have derived confidence from similar predictions, never imagining the words to refer to themselves, Maxentius’s line of battle at the Milvian Bridge suggests grave doubt, indecision, perhaps even ineptness. He nearly decided to stay in Rome and risk a siege, and many of the sources do indeed mock him for hiding behind its walls until the last moment. A few years earlier this tactic had worked against both Severus and Galerius, but an experienced military man like Maxentius must have felt goaded to prove himself in battle yet again.

He therefore led his men out to await Constantine’s approach. As the Milvian Bridge lay along the Flaminian Way, only two miles from Rome’s Flaminian Gate, he had the bridge torn down and crossed the river with his army a little farther upstream over a temporary bridge of boats. While this initial position upstream, near to a steep wall of rock, did offer his left flank some protection, his right began with their backs to the Tiber; and when the battle began, almost immediately his men shifted so that nearly everyone had the river behind them, forcing either victory or death in battle or drowning in retreat. “His very plan for arraying his forces proved that he was in a desperate state of mind and confused in counsel,” wrote Nazarius. He added that those last in his line, as if foretelling their awful end, had “the fatal waves” of the Tiber literally lapping near their feet.

While Maxentius’s troops, which some number as twice Constantine’s 40,000, included the loyal Praetorian Guard who had acclaimed him emperor in the first place, as well as legionaries and leftovers from the forces of Galerius and Severus, the majority of his regular troops, whether North African or Italian, were inexperienced and could not be counted on for affection or loyalty. By contrast, the army of Constantine had a pedigree of loyalty and success dating back to their time under the emperor’s father, and they had all fought together in Britain and Gaul for years. It was such a collection of men that faced each other near Rome, their lines extending hundreds of yards in either direction, on one of those warm early fall days in central Italy.

Aside from the regalia of the two emperors, Constantine is said to have worn a jewel-encrusted helmet, while Maxentius was outfitted in conspicuously splendid armor and clothing that helped identify his body the next day. Beyond that, both sides were essentially equipped equally. The cavalrymen of each side went into battle with a full array of swords, light javelins, two-handed lances, axes, and maces. In contrast, the infantrymen still carried the old standby short sword, the gladius, along with two long javelins, but they also would have had access to maces and clubs and even slings. They also had their shields, which in the case of Constantine’s army were decorated for good luck. Nearly everyone would have worn the bronze Roman galea helmet, and otherwise the mix-and-match of outfitting imperial armies from Britain to Babylon meant that a variety of body armor, whether leather or steel or both, was inevitable, as was protection for the arms and legs. In many cases men were fighting with or against weapons and armor that could just as easily be generations old or brand new.

For all this, though, the brevity of the ancient accounts suggests that the battle did not last for long. “A battle speedily finished should not seem to be longer in the telling than in the execution,” wrote the anonymous orator. Nazarius mentions both that the deities who were angry with Maxentius saw to his downfall, and that heavenly armies came to Constantine’s assistance. Whoever it was overlooking and influencing the scene, Constantine led his superb Gallic cavalry in the opening charge and, suddenly seeing their own cavalry defeated and now facing the full force of Constantine’s infantry, Maxentius’s troops broke for the bridge of boats. The Italians were especially reluctant to continue the fight, and the number of men who tried and failed to make it to the bridge simply glutted the riverside in a bloody snake of bodies and glittering weapons, or it cascaded them into the Tiber.

Somehow protected in retreat by the Praetorian Guard, Maxentius made it to the bridge only for it to buckle under the weight of so many men. “Pressed by the mass of fugitives, he was hurtled into the Tiber,” wrote Lacantius. It is here that the Tiber is said to have literally snatched him up “in its whirlpool” and devoured him, especially when he attempted to escape the water and make for the other side. The anonymous orator called on an allusion to Virgil to describe the breathtaking chaos of men and horses drowning in a crowd, or being carried downriver in the Tiber’s swift stream, or likely fighting each other for air and space in an attempt to save their lives, grappling onto the drowned or still living without a thought, or trying to free themselves from the armor that had only recently been their protection. Nazarius simply imagines the clogged river “moving along with weakened effort among high-piled masses of cadavers.”

Maxentius’ battle plan seems to have been doomed to such an end, and indeed the anonymous orator suggests “he sensed already that his fatal day had come and wished to drag as many as possible with him.” It is hard not to imagine this remark coming sarcastically, or perhaps with dread from the memory, from the mouths of Constantine’s own men or of Constantine himself, who witnessed the drowning death of fellow Romans they might otherwise have respected. Maxentius could be allowed no respect, though. His body was found the next day and decapitated, and his head was mounted on a spear.

Despite the parallels Eusebius saw between Maxentius’s death and how Pharaoh and his army drowned in Exodus, and therefore his equating Constantine’s vision and Moses’ experience of the burning bush, the Battle of Milvian Bridge was no definitive end. Even with three-quarters of his army in Gaul, the wars with the Franks continued. Constantine’s eastern ally, Licinius, was married off to Constantine’s sister; a few months later, in the spring of 313. It was Licinius’s turn to receive a divine message via a dream on the eve of battle, and upon his victory he and Constantine agreed to divide the empire between them. A year later they were fighting each other, and while Constantine eventually prevailed, and while he founded the city of Constantinople in 325, and in so doing literally reoriented the focus of the Roman Empire to the east, only a year later he had his son Crispus and his second wife Fausta put to death for supposedly carrying on together.

He also remained embroiled in political and religious controversy until the day he died, discovering that Arian and Donatist and Catholic Christianity’s disagreements could be as vicious as any battle. Although his are the words that many still say in church every week, his life and subsequent Byzantine history seem to suggest that, even for those granted visions of God, the lives of such isolated people remain nasty, brutish, and short.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments