By Susan Zimmerman

Much of what we know today about World War II are the visual images—both still and moving—that combat photographers took to document all phases of this costly human tragedy.

Millions of images were taken by professional and amateur photographers alike. Men who had been professional photographers before the war were enlisted by their governments to continue to ply their trade in uniform. Others were sent by their magazines, newspapers, and photo agencies to bring back dramatic scenes.

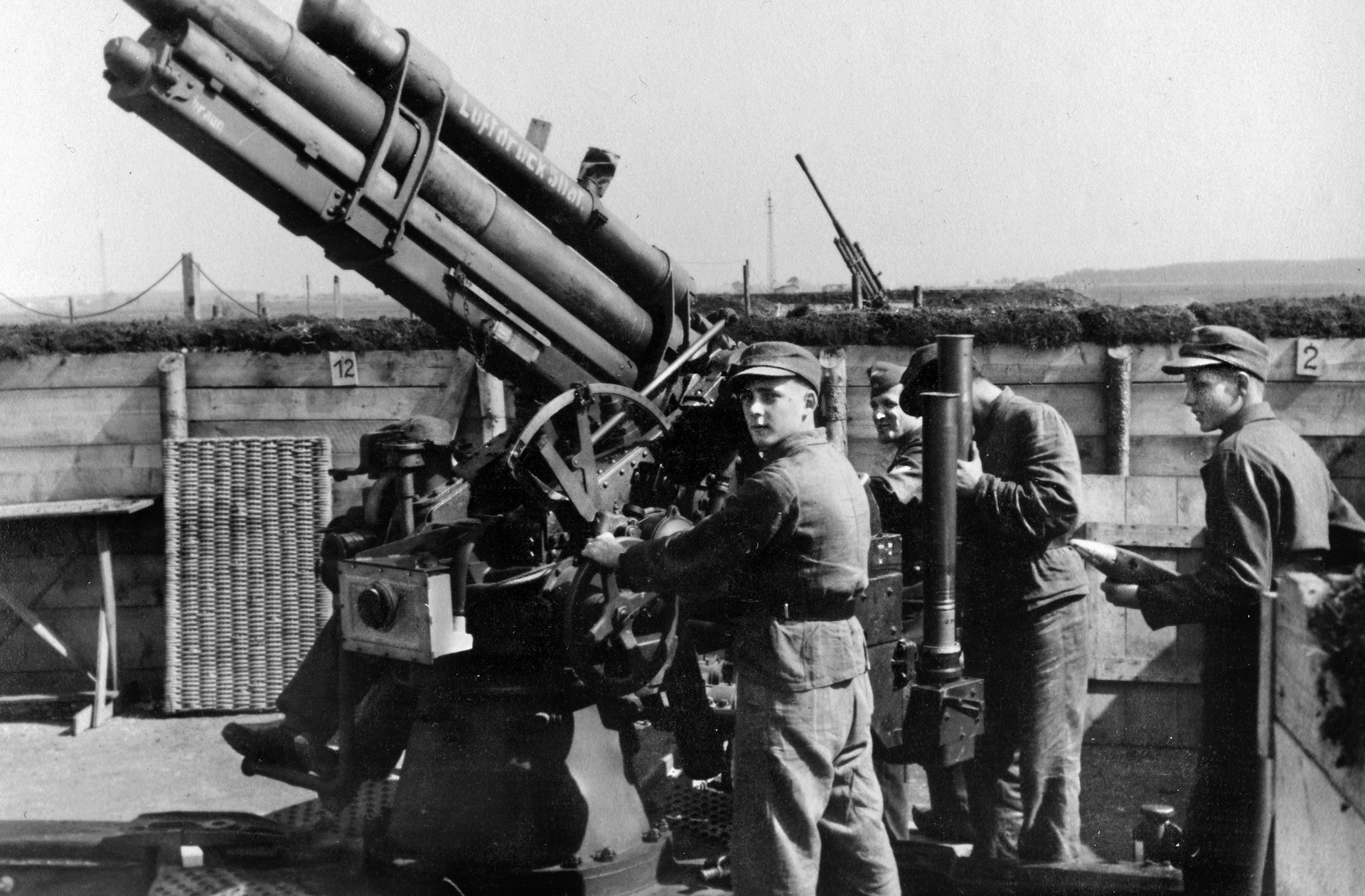

Even before U.S. involvement, the Germans were doing an excellent job of documenting their war in photographs and motion pictures. Formed into Propaganda Kompanies (PK), still- and motion-picture cameramen went everywhere the troops went, and their images often turned up in newsreels and such military magazines as Signaland Der Adler,not to mention the popular press.

The British, too, were devoted to making a photographic record of the war, and created the Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU) to do so.

As one can imagine, going into combat armed with only a camera was not without its hazards. Countless photographers were killed or wounded trying to cover the action, trying to get that quintessential shot that would tell people back home what war was really all about.

For example, of 1,400 U.S. Army Signal Corps cameramen in Western Europe during World War II, 32 were killed in action and more than 100 were wounded. Other lensmen serving with the Navy and Marine Corps also lost their lives trying to get “the shot.” Civilian photographers were not immune from danger; of 21Lifemagazine cameramen sent overseas, five were wounded and 12 contracted malaria.

Two months after Pearl Harbor, as the war expanded and the Army’s photographic needs increased, the U.S. Army took over the former Paramount Studios in Long Island City, New York, and turned it into the Signal Corps Photographic Center—later the Army Pictorial Center—which became home to filmmakers and still photographers who covered the war and who professionally produced hundreds of training films.

Once the center was established, the Army Pictorial Service became a major film producer. By either volunteering or being drafted, some of Hollywood’s finest directors, cameramen, writers, and technicians were assigned to the center, where they could apply their specialized talents. Many others with still photography backgrounds—newspaper and magazine photographers, editors, and darkroom technicians––also arrived.

By 1943, images from around the globe were pouring into the center by the tens of thousands, and the facility needed to greatly enlarge its storage capacity. By the end of the war, the library’s holdings amounted to more than 500,000 images.

World War II was the most visually documented event in history. There were millions of photographs taken by thousands of photographers during the conflict. Many photographs became famous, iconic. Who today doesn’t know Joe Rosenthal’s Iwo Jima flag-raising photo, Robert Capa’s blurry D-Day photo of a soldier struggling in the surf at Normandy, or Margaret Bourke-White’s searing image of emaciated survivors at Buchenwald staring with blank expressions at their Allied liberators?

These photographers, working for magazines or the wire services, had their photos published in magazines such as Life, Time, and U.S. News and World Report. They were called war correspondents and considered “civilian employees of the U.S. War Department,” so they wore officers’ uniforms with special insignia that indicated that they were official photographers.

But their military counterparts behind the lens have, for the most part, remained anonymous. Their photos simply bore the credit line “Official U.S. Army photograph” or “Official U.S. Navy photograph.”

“Most of our problem in the Army Pictorial Service was due to the fact that we were never credited when our photographs were published,” remembered William R. Wilson, a former lieutenant in the 162nd Signal Company, Photographic Company, Army Pictorial Service, during a 2002 interview. “Individual [Signal Corps] photographers were never allowed to be credited by name.”

Let us recognize four previously “anonymous” war photographers who deserve to have their names known and their work credited. A photo credit for one is a credit for all the thousands and thousands of unknown camera soldiers. The recollections of these four camera soldiers illustrate what it took to get the picture.

William T. Barr

William T. Barr, Photographer’s Mate First Class, served from 1942 to 1945 on Bougainville in the Solomon Islands, Leyte Island and Luzon in the Philippines, as well as in Formosa, China, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Ulithi in the Carolines, and Japan.

“I was a first-class photographer and one of my jobs was to man a movie camera which was mounted on the superstructure aimed toward the back end of the ship.… When the planes were landing … many of them were badly shot-up, [so] my job was to photograph the planes that were having difficulty landing, and take pictures of whatever happened. I did get movies of several crash scenes and some of those showed up later in the United States in a movie called the The Fighting Lady.

“Other jobs that I had, when we were under attack, we would grab cameras and go onto the flight deck and take pictures of ourselves being attacked and the Japanese planes coming at us, but primarily we would take pictures of the [enemy] planes hitting nearby carriers and nearby ships, and we got a lot of excellent pictures of such action.”

One day a Japanese plane dropped a bomb onto the flight deck of the Enterprise,but it failed to explode. Barr recalled, “Our planes were coming back from a strike and they were in pretty good shape so I was not assigned to the movie camera at that time. I was wandering around on the superstructure with a camera in my hand, and our planes were landing one after another. In came the last plane, and to everybody’s horror, they realized it was a Japanese plane.

“He had simply gotten into the landing pattern and nobody noticed it. [He] came roaring over the Enterprise and dropped a bomb but, because of his low altitude, the bomb didn’t have time to point downward. When a bomb hits a ship, it’s usually coming straight down, and the explosion is activated by a device in the front of the bomb.

“So this bomb landed on its side and bounced and bounced and came to a stop. And I am looking down at it with horror from the superstructure, and I figured it was a time bomb. And so I thought I’d better get the heck out of here, but the gunnery officer spotted me and he said, ‘Barr, you go down there and get a close-up of that bomb. I want a close-up of the markings on the bomb.’

“And I said, ‘But sir, it’s a time bomb. It will go off any second.’ And he said, ‘Bosh, it’s not a time bomb. Get down there and get the pictures.’ So with my heart in my mouth I went down to the flight deck and got as close as I could to the bomb, took the pictures, and raced at top speed away from it. The pictures came out, and they were sent back to the United States and, of course, copies were given to the gunnery officer.

“[It turned out] it was not a time bomb. And to give you an idea of the courage of the men on the ship, after I had taken the pictures, about 10 men calmly came up to the bomb and rolled it off the back end of the ship, into the water.”

When he was not involved in taking photos or making movies, Barr was observing life aboard a carrier in an active war zone.

“While I was stationed on [the Enterprise], we were involved in eight battles: the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the attacks on the island of Luzon, the attacks on the island of Formosa, the attacks on the China coast—all of which were occupied by the Japanese. Then we raided the Japanese island of Honshu and also the Japanese island of Nansei Shoto.

“Then we were stationed off of Iwo Jima, so we were involved in that battle, bombing the Japanese positions at night. At that time we were a night carrier. And then the Japanese island of Okinawa; we were off the huge island for about six weeks, constantly bombing the Japanese positions at night. That was the last one I was in.

“[I remember] in December of ‘44, Air Group 90 came aboard, and they had been trained in operating at night using the radar screen in their airplanes, and so our ship worked with them closely to finish up their training. Beginning in January they began bombing Japanese positions at night and flying at night using simply their radar to locate the Japanese islands and to locate the targets; it turned out to be quite successful.

“The Enterprise, with this Air Group 90, was the only ship that was specifically trained in night operations…. These night operations were successful insofar as they not only did a lot of damage but they kept the Japanese awake all night long, and that must have been very hard on their morale––they never had a chance to sleep.”

Barr noted that, of the 22 battles the Enterprise was in, the worst damage was done on May 14, 1945. “[General] quarters sounded, and we were up on the ship with cameras. I just happened to be in the photo lab at the time the Japanese planes came at us. [It’s] interesting down in the photo lab; you couldn’t see what was happening but you could hear the 5-inch guns, which could shoot a long way. You could hear them pounding away, and we figured, well, the Japanese are 15 miles away.

“Then the 5-inch guns would stop, and the 40mm guns would start firing; their [range] is about two miles. So we knew that the Japanese were within two miles of our fleet. They were aiming for the carriers, which were in the middle of the fleet. We were surrounded by smaller ships extending out, oh, 10, 15 miles.

“While we were all looking at each other worried, the Japanese were getting close. Then the 20-millimeters started, the ones that fire at incoming planes. They’re very effective for up to, let’s say, a half a mile, so we knew the Japanese were diving on us, and then we felt the ship shudder.

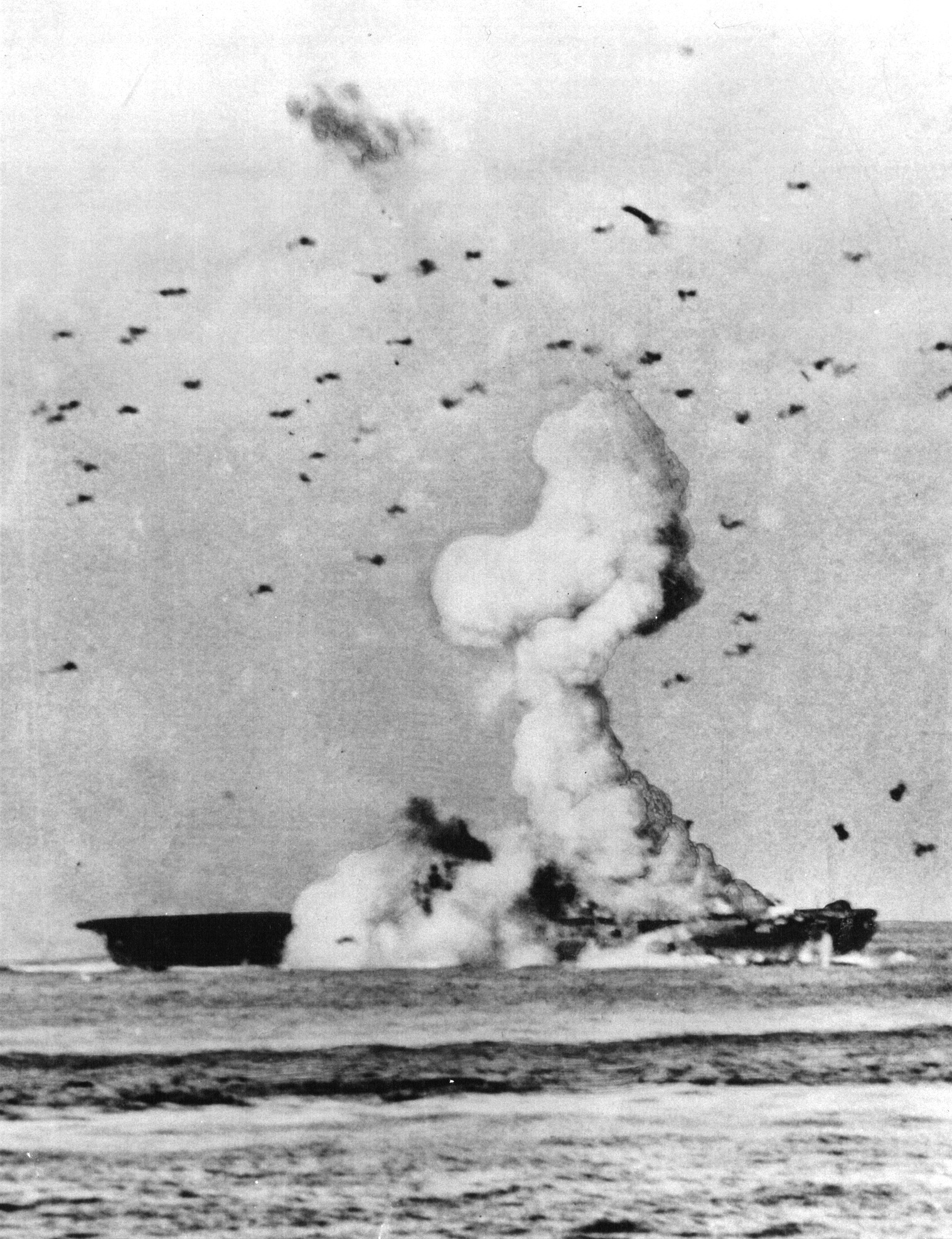

“We didn’t hear the explosion, but we felt the ship shudder and we knew we had been hit. So we grabbed cameras and went up on the deck, and we photographed what we could of the flames, and the fire and the damage. The whole fire was put out in about a half hour, but the nearby ships took some great pictures of the Enterprise aflame.

“One Japanese kamikaze had dived in beside our no. 91 elevator; [it] went down about five decks before his bomb exploded just below the no. 1 elevator. It must have been a 1,500-pound bomb, maybe a 2,000, but it blew a large chunk of the elevator up and up and up into the air. One of the nearby ships took a picture of that huge chunk of elevator 400 feet up in the air. Other ships kept taking pictures, and ultimately I got a picture of it, that elevator over 800 feet up in the air.”

The carrier was badly damaged. Barr said, “We were able to keep moving, but we were unable to operate any guns. After about two hours the Japanese retired, and we headed for an island called Mog Mog, which had a huge harbor where we would be safe. So we went to this island of, well, actually it was the Ulithi Anchorage—Mog Mog was just one of the islands. And from there we were sent back to the United States to be repaired.”

Barr recalled another incident: “It was at night, and the whole fleet was surrounding us, while the Japanese were looking for the American Fleet. So the entire fleet was blacked out––not a light was shining because, obviously, if you turned on a white light, the Japanese would spot it and would head for it. The only lights that were visible were these dim red lights, so we got around on the ship with these dim red fights and it was safe.

“But [one of our] planes had come in. It was badly damaged, and dusk had fallen and they were about to push the damaged plane over the side when somebody said, “That is a photo plane and the gun camera has pictures of the shoreline where the Marines want to land. This gun camera has movies of the shoreline revealing any hazards, so that is a badly needed movie film that the Marines need to see if it is safe to land there––if there are any huge rocks or anything.”

“So the captain said, ‘Okay, get the gun camera out of there and then we will push the ship [plane] over the side.’ They looked around for a photographer to get the gun camera, and there was I. So they said, ‘Go down there and get the gun camera out of that plane,’ and I said, ‘Well, I can’t do it [without] a flashlight or a spotlight,’ and someone said, ‘If we turn on a light the Japanese might spot us.’ And then the captain said, ‘We will turn the searchlight on that plane, and you go down and get that gun camera out of the plane.’

“So I got down to the plane and I climbed up to where the gun camera was and they switched the searchlight on me. Here in this giant area of the Pacific with the Japanese looking for us, any plane up in the sky would see this spotlight shining on the plane [with] some dumb photographer trying to remove it.

“Anyway, I was able to quickly get the gun camera disengaged and got safely away from the plane. They turned the searchlight out, and you can bet I was quite frightened because, you know, if the Japanese had been even within a mile they would have spotted that light and come right at us. So I was lucky.”

Throughout the war, whenever carriers were attacked, often the flight deck was covered with planes loaded with fuel, bombs, rockets, and other ordnance, ready to take off. During an attack, these flammables and ordnance could catch fire, resulting in countless explosions and casualties.

“Most of the time when the Enterprise was hit, they did not have a flight deck full of gassed-up planes, and so probably an element of luck there,” Barr said. “We were badly damaged several times, but we also had an unbelievably well-trained deck crew. The minute we were hit with a bomb, they would race out there with their hoses and extinguish the fires, like on May 14 when we were hit by this kamikaze that basically took us out of the war. They put that fire out in under 17 minutes—it was incredible.

“We got a lot of pictures of the flight deck covered with men fighting the flames and the fire, and it’s just magnificent to see how fast they worked. So true, we were lucky, but we also had a highly trained crew.”

Emil Edgren

Emil Edgren, U.S. Army Technician 4th Class, served in Iceland, England, France, and elsewhere in the European Theater while assigned to the 3908th Signal Service Battalion from 1941 to 1945.

He recalled that while stationed in England his assignment was to cover the bombers returning from raids over Germany. “It was not a very good sight to see the damaged planes return and some of the crew being removed lifeless from the B-17 Flying Fortresses. As the planes came in, I held my breath and said a prayer. Those guys in the planes were the real heroes. When some were given a pass to London, they would have one hell of a time and rightly deserved it, glad to be alive.

“One day a fellow photographer came up to me and said he was to fly with a plane to deliver supplies to some troops. ‘It will be nice,’ he said, ‘as they will open a side door so we can [take] photos of the drop. Why don’t you come along?’ I told him not this time, as I was working on my camera. I was trying to cover some of the chrome on my Speed Graphic 4×5 camera. It would be a real target if I got near any enemy.

“He was the nicest guy from New York. He left on the plane but never returned. He was shot down somewhere in France. It shook me to think how close I had come, and I never again took another day for granted. I can still see his smile that day and hear his voice coaxing me to go along. It was the price of war and a reminder that even a photographer was at risk. Enemy fire did not discriminate.”

That wasn’t the only time Edgren wondered if he had a personal angel watching over him. One day he was late for breakfast. “It was not long after the plane incident that I left my billet to walk several blocks for breakfast. What greeted me was a gaping, smoldering hole where the dining room and kitchen had been. A V1 rocket had hit it, taking with it the staff and the GIs gathering for breakfast. If I had been on time.… I tried not to think of that as I stood there in horror, watching the smoke rise and listening to the sirens. That is the kind of picture that lingers in the mind.

“While in Salisbury, the editor of the local paper asked if someone could take some photos for the paper as the Duchess of Kent would be visiting Salisbury. The paper had managed to stay in business, but its photographer had been lost to war. It was another slice of fortune for me, and I was in the right place at the right time. I made some points there, and the general’s public relations man, Lieutenant Berger, wrote me a nice commendation.

“Soon after that event, I got my transfer to London to the Army Pictorial Service [Army Signal Corps]. After all the kicking around, London was like heaven. We were billeted in some nice quarters with good chow. My company commander was Major McAlister, and his secretary, Virginia, was a WAC [Women’s Army Corp]. We were given assignments and sent all over Europe, sometimes by plane or jeep.”

Dodging buzz bombs in London was as routine as walking on the beach in Seaside, California, during basic training at Fort Ord. At least Edgren was where he wanted to be and doing what he wanted to do: photography.

He had been in London about eight months when he had the privilege of photographing the Queen Consort, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, wife of George VI. “She wasn’t the least bit standoffish or elitist,” he recalled. “I was surprised that she was pleasant to me, a foreign Army photographer. I talked to Her Majesty and told her about California.”

Finally, after Paris had been liberated in August 1944, Edgren’s outfit got orders to ship off to France. “I did not know it at the time, but I was on the last leg of my journey to the Place de la Concorde [in Paris]. Fates were set in motion for that one moment in time when history would unfold in front of my lens.

“While the Nazi presence wasn’t as pronounced as it had been, there were still signs that they had been there and always the threat that they would return. The French weren’t convinced that the Nazis were gone. The war still went on, and the echo of the bombs stayed with them, even if the sound was only in memory. It was not a memory anyone wanted repeated. There was an uneasiness about Paris that superseded any pleasure of being there.

“The [photographic] battalion was set up in the heart of Paris. Our living quarters were nothing like regular Army. It was a beautiful apartment with maid service to make up our beds. I was on the third floor, and rarely did the maid make it up there, especially if she was good looking. The Rothschild Mansion was just a block away—an example of the fancy area we were in. Just as in England, the luxury did not hide the scars of war or the fact that the war was still ablaze around us.

“At our office, five of us waited for assignments. As we got an assignment, Major McAlister’s secretary, Virginia, made all the arrangements, such as transportation and length of time to do the job. If you were nice to Virginia, she would tack on a few extra days. It was great, so when you got back, you didn’t need to report until your time was up.

“The war was still going on. My assignment was to join the 82nd Airborne Division on a glider operation into Holland. I was at an English airfield and briefed on where we were to land. Three times, I sat in the glider, but each flight was aborted due to bad weather. I called the major and he said to come in. I left in a jeep, and the next day the invasion took place. It was a disaster. I was lucky on that one. My angel was still with me.

“Later, I was sent with a movie man, Herb Shannon. We were to report to the 82nd Airborne, as the Battle of the Bulge had started. We were pretty much on our own. We latched up with regimental headquarters and ended up in a small, deserted village in Belgium. Everyone had left, so we had our choice of houses.

“It was December and very cold. Winter in Belgium took second place only to winter in Iceland. We picked a house and put our sleeping bags upstairs for the night. In the morning, we grabbed our mess kits and headed for the field kitchen. Help! The whole regiment had moved out during the night!

“There we were, on our own, with the Germans on the march in our direction. I fancied I could hear the German regiment. I was positive they were out there, right beyond the edge of the trees. Shannon and I hurried out of there, looking over our shoulders at every sound, expecting at any moment to hear a German voice shouting, HALT! We finally followed the tracks in the mud and caught up with the regiment.

“While covering the front line, I was able to get a good photo of one of the 82nd guys running to help his buddy as the Germans were firing at us. In that exchange, several of the enemy were killed and no one on our side was killed or injured.

“It had been about a week, terribly cold, and I was dreaming about Paris. Finally, a new lieutenant from headquarters found us. ‘Been trying to find you guys. I have a message, and you guys are to report to Eagle.’

“I knew this guy did not know about Eagle. Great! ‘Eagle’ was the code name for Paris. ‘Well, if you guys say so.’ We jumped in our jeep and off to Paris we went.

“We reported to Major McAlister in Paris. ‘What are you guys doing here?’ he said.

“We said, ‘Lieutenant Sheldon told us to return.’ We found out later Eagle was not Paris but an Army Corps headquarters. I always felt rather bad. We no doubt got the lieutenant in trouble.

“In retrospect, it’s strange how pieces of fate fell into place. I was in the right place at the right time, and on May 8, 1945, I stood in the Place de la Concorde and swept my camera over the gathering crowd. General Charles de Gaulle’s voice came over the loud speakers from the opera house. ‘The war in Europe is ended. Germany has surrendered. ‘Vive la France.’”

Charles Rosario Restifo

Charles Rosario Restifo was stationed in the Pacific Theater, Philippines, and Japan while serving as a staff sergeant in the Army Signal Corps from 1942 to 1945. There he was assigned to follow General Douglas MacArthur, then later sent to photograph Hiroshima immediately after it was bombed.

“As a combat photographer in the U.S. Army Signal Corps in charge of our unit in Bougainville,” Restifo said, “I was present at meetings in March 1944 with Maj. Gen. Oscar Griswold and Colonel Harry C. Hull during planning sessions for landings on Leyte and Luzon in the Philippines. These landings were part of General Douglas MacArthur’s plan to return to the Philippines, liberate the Americans who were left there in 1942, and ultimately to use the Philippines as a stepping stone for a landing in Japan. I received a letter of orders dated March 21, 1944, that I would be attached to XIV Corps Headquarters, under the command of General Walter Krueger.

“The master plan was a huge operation and would include land, sea, and air equipment and personnel. Three men of our Photo Corps would remain in Bougainville with the trailers and equipment. Three men and I were to go to the Philippines––to Leyte, Lingayen Gulf on Luzon, and eventually south to Manila, over 2,000 miles from Bougainville.

“October 20, 1944, was marked as ‘A-Day’ for landing on Leyte. This was the first return of the Americans in the Philippines since leaving in defeat in early 1942. After bombarding the shore and an exchange of fire between American troops and the Japanese on the Leyte shore, General MacArthur descended from his cruiser over 30 months after he left the Philippines humiliated by the loss and waded ashore in knee-deep water, accompanied by Philippine President Sergio Osmena and Resident Commissioner Carlos Romulo.

“Even though gunfire was still evident, MacArthur walked to the beach with his landing party with only a pistol in his right-hand pants pocket. This was a very emotional moment for MacArthur, and he wanted to let the Filipinos know he had set foot on their land. Therefore, he immediately broadcast from a field radio with President Osmena next to him, ‘People of the Philippines, I have returned.…’

“Now MacArthur’s giant preparations for landing on the western side of the Philippines at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, could begin. Almost 1,000 ships, 3,000 landing craft, and 208,000 men were assembled. General Krueger, who had been at Leyte, was the leader of the Sixth Army ground forces.

“The actual landing was at two points on the Lingayen Gulf beach. I was with Maj. Gen. Oscar Griswold’s XIV Corps, and we were to hit the western beach. Air cover was also ready. S-Day was 0700, January 9, 1945.

“I was aboard the USS Mount Olympus, a communication ship skippered by Admiral Ted Wilkinson. The trip from Leyte to Luzon was about 400 miles by land but more by sea. At dawn on S-Day I was awake at 0400. In the dim light I saw hundreds of ships of all types as far as the eye could see: aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, landing craft, etc. It was quite a spectacle.

“All ships were on red alert. Numerous kamikaze planes and small suicide boats were hitting our ships and causing havoc. At precisely 0700, heavy battering from the U.S. ships hit the shoreline. Flares went up indicating General Krueger could commence sending his men to the beach in small landing craft.

“I was preparing to climb over the side of the ladder to a small boat when a kamikaze plane hit the deck and was splashed.

“The men landed on the beach in hundreds of landing barges that opened in the front to enable the men and equipment to exit and wade to shore departing about five to 10 minutes apart.

“I was on the fourth wave. I wanted to photograph the backs of the men and the landing craft as they reached the shore as well as the Japanese on the beach. Some men in the second wave hit a sandbar. Then the coxswain opened the landing gate too soon, and some men stepped into six to eight feet of water. I could see them scrambling to get out from under their heavy equipment. A few men were drowned. There was very little gunfire returned by the Japanese. Most of them had run inland after the bombing from the ships and took cover in the trees and oliage.”

With the liberation of the Philippines, the fall of Japan was not far behind.

Restifo continued, “After the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima [on August 6, 1945], we did not know what it was all about, as we had never heard of an atom bomb. I was ordered to go to Japan in charge of two photographers to take photos of the area. We were the third plane to land in Yokohama, Japan, from Manila. In order to get on board, my group bumped about 50 other personnel off the plane who were high rank but lower priority. Besides ourselves, we needed space for a jeep and equipment to go with us.

“The rendezvous was to fly to Guadalcanal, then from there at 0300 to board a C-47 for the four-hour flight to Yokohama. On arrival at 0700 in Yokohama we found the Japanese lined with vehicles to transport us. They had been ordered to do so by General MacArthur from Manila. They were pale and scared, as they had been told by their supervisors that the United States forces would execute them all.

“We flew to Hiroshima and took photos. The city was still smoldering, charred to the ground from the fires that devastated it after the actual bombing. An occasional wall remained of a huge city. Japanese were dazed and in a state of confusion, running, crying, wailing. They displayed many burns and blisters. Some were carrying umbrellas against the drizzly rain. The ground was wet. Many were dead. We took our movies and photos. Some Canadian photographers had run out of film, so we gave them some of ours.

“There was an American medical group that approached our photographic team, requesting photographic coverage. They were asking Washington for 200-, 400-bed hospital units to be flown to Hiroshima to be [supplied] by the SeaBees. The hospitals would include medical teams, nurses, beds, supplies, medicines, and shelter.

“After all, we were just as interested as to what happened here as the Japanese were. There had never been an atomic bomb explosion over a populated area before. The U.S. wanted to help as well as find out about injuries and effects on the human body from atomic bombs.

“Within the week after the bomb explosion, all preparations from the hospitals were underway. A few days after my visit, bulldozers flown in by the U.S. Army were clearing the land and rubble. The Army had gathered the survivors into tents. Generators were giving power, and food was made available. The mighty power of the USA was about to care for and treat the very persons they had bombed and who had bombed us in Pearl Harbor. My personal assignment was to return to Tokyo.”

In Tokyo, Restifo requested permission to photograph the Imperial Palace and was able to record a meeting between Emperor Hirohito and General MacArthur. “The palace was surrounded with the remains of a beautiful garden and moats with a cross bridge. The Emperor wore a formal top hat, black suit with tails, and MacArthur in his usual tans with his battlefield squashed, peaked cap, open-neck shirt, and no tie.

“In between the bombing of Hiroshima and the signing of the surrender, our mission was to record conditions in the city and surrounding areas including the Diet [the Japanese Parliament].

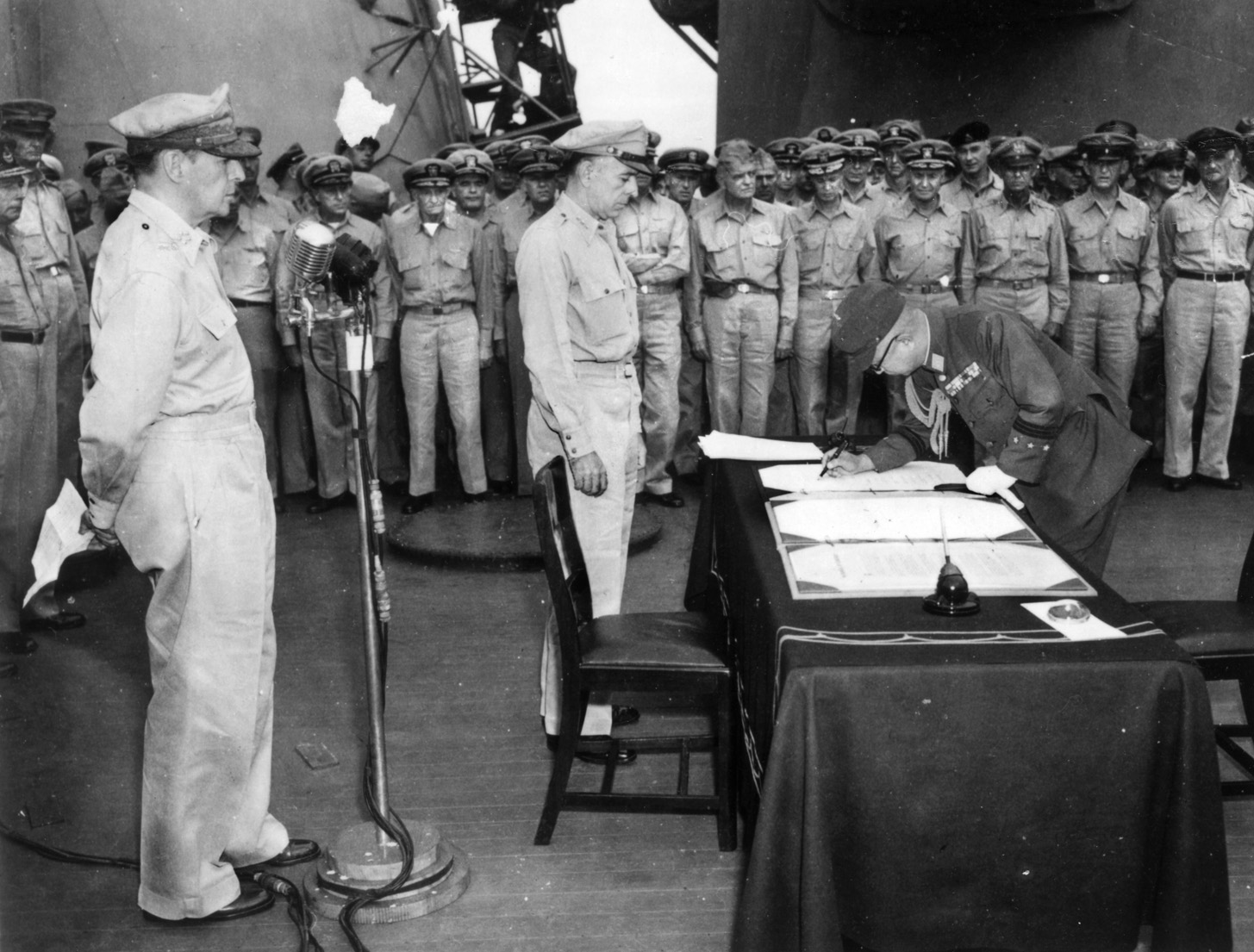

“On September 2, 1945, the day of the signing of the surrender of the Japanese on board the USS Missouri,two men and I headed for the ship. On deck was General MacArthur in his open-collar tans and the Japanese representatives in formal attire with top hats, along with several Japanese generals. Top brass from each branch of our armed services and Allies were present. Hanging over the rails watching the historic event were thousands of sailors and soldiers who had been in the Pacific for so very long being shot at by the Japanese and who had lost many comrades.” Restifo’s photographs of the signing ceremony continue to appear in various publications.

William R. Wilson

Lieutenant (later Captain) William R. Wilson served in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy while serving in the 162nd Signal Company of the Army Pictorial Service from 1941-1945. He recalled the influences from Hollywood photographers and the issue of photo credits.

“One morning, Hollywood’s gift to the American Army—the name was Daryl Zanuck; you may have heard of him—had the idea of shooting both still and motion pictures of the invasion of North Africa when he came aboard the Derbyshire and found my men and me. He was the only full colonel—what we call a chicken colonel—who ever wore diamond-studded shoulder insignia!

“At that time, all of our equipment consisted of Speed Graphic 4×5 cameras and Bell and Howell Eyemo motion picture cameras, but Colonel Zanuck brought us 35mm Kodak 35s, all metal and painted olive drab. My unit got three of those, I believe, and a beautiful scenic Kodak special 16mm movie camera, which later wound up on the bottom of the Kasserine River. My sergeant, Larry Mueller, threw the camera in the river and then swam the river to get away from the Germans during the Battle of Kasserine Pass.

“During my postwar encounter with a lady in the Pentagon, she said, ‘The photographs that you produced during World War II are the finest that we have in our files.’ And I said, ‘Well, do you know why that was?’ She said, ‘No, why was it?’ I said, ‘Because they were all shot on 4×5 negatives.’

“They weren’t shot on 35mm film as most of my unofficial pictures were, but they included an air raid picture which was picked as one of 26 great photographs of World War II. It was published in a booklet, printed by the manufacturer of our Speed Graphic cameras—I have several copies of that publication. On the cover was a picture of an exploding depth charge made by a Navy photographer. My picture, which I entitled ‘Hell over Oran,’ was the double-face centerfold in the booklet.

“You know, everything was not sweetness and light with the Army Pictorial Service because there were two factions of Army photographers. There were the photographers from the old school, including some that were graduates of the Signal Corps Photographic School of Astoria on Long Island, and then there was the Hollywood gang that came out of California, and there was very little respect between the two groups. Most of our problem in the Army Pictorial Service was due to the fact that we were never credited when our photographs were published. Individual photographers were never allowed to be credited by name.

“I’ll tell you the story about the one Signal Corps photographer who received credit for his pictures when they were published. He was from the 165th Signal Photographic Company. He conceived the idea that when he went on the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944, he was going to take with him a carrier pigeon and he was going to shoot a roll of 35mm film and then attach the little film canister to one of the legs of this carrier pigeon, and then he would aim the pigeon toward England and toss him up in the air and in due time he would arrive in England along with the first combat photos of the D-Day invasion.”

Wilson continued, “But the best laid plans, you know, sometimes have a way of not working out. The pigeon became disoriented and, instead of flying north toward England, he flew south over the German lines. A subsequent issue of the German Army newspaper published a splendid layout of American Army photographs complete with identification of the young lieutenant from the 165th who shot the pictures, and that was the only instance I heard of where an Army Pictorial Service photographer got credit.”

Emil Edgren remembered that one of his buddies, Sergeant Frank Kaye, was the one involved in that incident. He said that Kaye “had a 35mm camera and a small cage of trained pigeons on his back during the landing. Upon landing, with a roll of film attached to the pigeon, he sent the birds off to London. No way. The pigeons were never trained to fly over water, so he watched helplessly as they flew back in the direction of Germany, not over the English Channel. I think Frank was never the same after that snafu. I always wondered if the Germans developed the film.”

Wilson concluded, “Official photographs that my unit made carried a complete caption and the name of the photographer. But not until we got home and went through the World War II copies of Life magazine that we had all missed in Europe did we recognize some of our own pictures published in Life and Look and various other sources, including the Army’s official photographic history of the Mediterranean Theater part of World War II.”

The widow of Charles Restifo, Beatrice, told this author, “My husband followed MacArthur; some of [his] photographs are famous, some of them are not. He was very proud of being in the Army. I still have his jacket that says ‘war photographer.’ All those photographers, so many have passed away. They all had a lot of stories … they died with them.”

But not all is forgotten. The stories of these four camera soldiers honor those hundreds of others who shot the war and toiled in anonymity for the benefit of history and humanity.

As one combat photographer said, “The people of today, of my time, and the people of tomorrow, and the tomorrows thereafter, will see this historic moment that I saw. They will see it through my eyes.”

POSTSCRIPT: The Veteran’s History Project (created by the Library of Congress) collected these firsthand remembrances of American wartime veterans used with permission of the Veteran’s History Project. William T. Barr’s excerpts are from a 2002 interview with his daughter Sally Ainsley. William R. Wilson’s excerpts are from a 2002 interview.

Excerpts from Emil Edgren’s self-published book 3:01 P.M. Pacific War Time: A Photographic Memoir—Victory in Europe, as told to Gale Geurin, are used with the author’s permission. Excerpts from Autobiograpy of Charles Restifo are used with permission from his widow Beatrice Restifo.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments