By Richard A. Beranty

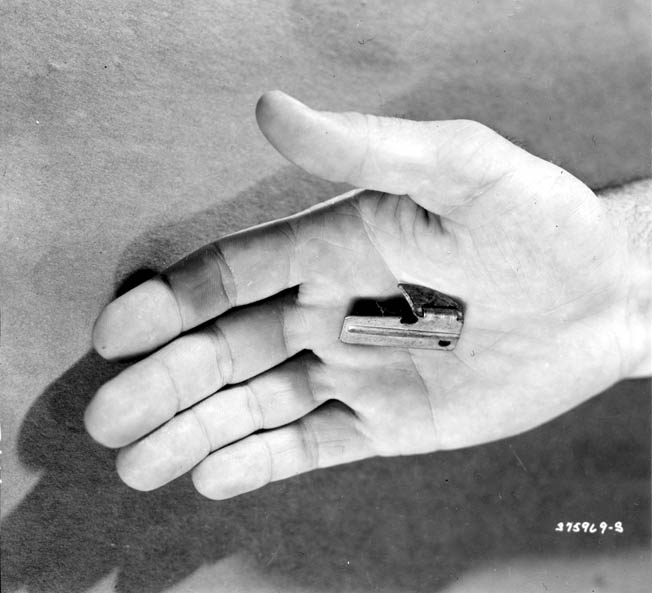

Far down on the list of important inventions essential to victory in World War II is a modest gadget built of stamped metal called the GI Pocket Can Opener—commonly known as the P-38 can opener—which was used by American troops in the field to sever the lids off combat rations. Despite its small stature and relative obscurity, many consider it to be the most perfect tool ever developed by the U.S. Army.

Simple in design, efficient in use, and diverse in application, the P-38 was an ideal complement to the canned meat and bread components contained in C-Rations, a staple of military feeding for more than four decades. The little two-piece hinged device constructed of hardened steel never seemed to break, never lost its edge, and its rugged versatility always provided a quick solution in situations other than its original intent. Soldiers regarded the P-38 as their personal, government-issued Jack-of-all-trades.

“When we had C-Rations, the P-38 was your access to food, making it the hierarchy of needs,” retired Army Colonel Paul Baerman told the Army Times. “Then soldiers discovered it was an extremely simple, lightweight, multipurpose tool. I think in warfare the simpler something is and the easier access it has, the more you’re going to use it. The P-38 had all of those things going for it.”

More Than Just a C-Rat Opener

The official Department of Defense nomenclature for the cutting utensil is Opener, Can, Hand, Folding, Type I, jargon longer in print than its actual 11/2-inch length. Sealed in a paper wrapper to ensure cleanliness and packed inside combat rations, GIs soon realized the small opener with the long-winded title could do much more than open C-Rats. In a pinch it might be used as a screwdriver to help field strip a weapon, cut seams on a uniform, or scrape mess kits clean. To accomplish a mission it could strike flint, measure inches, strip wire, deflate tires, adjust a carburetor, or pick inside a wound. Need a box cutter, marking tool, or decorations on a makeshift Christmas tree? The usefulness of the P-38 seemed boundless, and like many great inventions its origin was humble.

Limited financially because of the Great Depression, the U.S. War Department in 1936 allocated a minimal amount of funding through the Quartermaster Corps and opened a facility on Pershing Road in Chicago called the Subsistence Research and Development Laboratory (SRDL). The lab’s function was to test new foods for the Army and design modern methods of food packaging. By 1942, the original three-man staff had increased to 22 when commanding officer Colonel Rohland A. Isker sought out area metal fabricators to mass produce an inexpensive hand-held can opener with a sharpened and curved cutting blade that could be carried in a soldier’s pocket.

The Inspired Design Behind the P-38 Can Opener

Isker, a forward-thinking career officer who harbored an interest in cookery and the science of food technology, was a chemistry major at the University of Minnesota when he joined the National Guard in 1915, served on the Mexican border in 1916, and trained U.S. officers during World War I. He remained on active duty between wars as a cavalry officer in the Philippines, China, Siberia, and Japan, critical learning experiences that proved useful when he assembled his team at the SRDL.

Under Isker’s command, a small cadre of talented chemists, bacteriologists, home economists, food acceptance specialists, and packaging engineers developed the first logical, comprehensive, and effective ration system ever used for operational feeding in U.S. military history. The lab also created emergency Ration D, assault Ration K, the 5-in-1 and 10-in-1 mess packs, all necessary for the well-being of 16 million American troops serving in all climates and conditions across the globe.

The amalgamation of government with nearly every aspect of American industry was common during World War II, and three firms quickly responded to Isker’s can opener challenge—Washburn Company of Rock- ford, Illinois, Bloomfield Co. located in Chicago, and Speaker Corp. of Milwaukee, Wisconsin—the only makers of wartime P- 38s. Their production was based on a number of U.S. patents awarded for a handheld opener, the first in 1913, a second in 1922, and two others in 1924 and 1928. But new patents do not require improvements, only design changes, and the opener supplied to the Army during the war lacked one key operation for military liking: a locking mechanism that kept the cutting edge in place when the P-38 can opener was not in use. Without such a feature, the blade was prone to open and cause cuts or rip holes in pockets.

Isker explained the problem to John W. Speaker, a native of Austria who since 1935 operated a metal shop in Milwaukee that man- ufactured automobile accessories. Born in 1903, Speaker studied engineering at the University of Vienna, immigrated to the U.S. in the 1920s, and eventually served on the Industrial Committee of the War Production Board during World War II. He worked closely with SRDL personnel and developed a means by which the blade of the P- 38 remained in a closed position. Speaker called the improvement a “detent” in which two small lugs or protrusions on the opposite side of the hinge connection kept the cutting edge shut with spring-like tension. Motivated by patriotism for his adopted country and abhorrence of Hitler’s Germany, Speaker signed a royalty-free, non- exclusive contract for his design with the U.S. Office of Patents in full knowledge that other makers would profit from his detent innovation.

First Use in Combat

The Army first used the opener in 1942 taped to emergency parachute or “bailout” rations that were supplied to air force crews. The C- Ration, which began large-scale production a year earlier, was initially manufactured with an opening key soldered to the bottom of each tin, which made for its own easy access. The key pulled off, threaded a metal strip built into the can, and opened with clockwise turns, a contrivance familiar to civilian consumers of SPAM and canned sardines. But the method was costly with the millions of combat rations being made and was slowly phased out in favor of the less expensive P-38.

John A. Speaker, who took over the family business after his father’s death in 1960, said making can openers for the government was competitive. “Shortly after I became president of J.W. Speaker, the first contract I bid on was a Department of Defense solicitation for 10 million P-38s, with a rider for 10 million more,” he said. “The bid was about $12 per thousand. We were the low bidder and we beat the competition by one cent per thousand pieces. After the bid opening, my competitor called to congratulate me. We were not the only suppliers of the can opener to the government.”

At least 12 companies made the P-38 in its 40 years of production for the Army. Speaker estimated his company produced some 50 million from 1942 through the 1970s and has tried to learn from the Defense Supply Center Richmond under the Freedom of Information Act how many can openers contractors made for the government. “Unfortunately, they don’t seem to have the information,” explained the 85-year-old Speaker.

Manufacturing numbers for the P-38 soared following World War II to meet the Army’s increasing demand. Luther Hanson, curator of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Museum at Fort Lee, Virginia, estimated 750 million P-38s were produced during World War II and the Korean War and over one billion since. The more that were made, the less expensive they became. Dur- ing its peak years of production, the cost to manufacture one P-38 in quantities of 10 million or more, envelope included, was approximately one cent. In times when other military items con- tracted by the government were purchased at ridiculously high prices, the penny pocket can opener holds the distinct honor of being the most massed produced and least expensive tool ever created by the Army.

Learn to Use a P-38, or Go Hungry

Millions of GIs learned early in basic training how to use the P-38 or else go hungry. First a puncture is made with the point of the blade along the top rim of a can. In a rocking motion the cut is advanced forward, toward the user, with a downward shearing action. The opener is held in place along the can’s underneath rim by a notch built into the handle just below the cutting edge and “walked” around the can until opened.

Military specifications were exact and clear as to manufacturing guidelines. The opener had to be made of heat-treated carbon steel and tin plated to prevent corrosion. It was marked “U.S.,” stamped with the manufacturers name or trademark, and to facilitate cleaning, a hole was put in the handle. The P-38 was folded flat, heat sealed inside a small envelope of unbleached Kraft paper, and printed with a diagram and written directions for proper use. Directions also advised that to sterilize the opener, tie a string through the hole and immerse it in boiling water or heat it with a match before reuse. The unassuming hole in the handle turned out to be a special feature allowing GIs to secure the P- 38 to their key ring or hang it around their necks from a dog tag chain.

The origin of the P-38 name is somewhat unclear since those in uniform often develop a lexicon for equipment and duties common to their branch of service. Two other World War II creations are more noteworthy namesakes than the P-38 can opener—the U.S made Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane and the Walther-designed German P-38 semi-automatic pistol—but neither one had anything to do with its naming. Some have suggested the name came from its length—38 mm, which is equivalent to its 11/2-inch size, but that is unlikely since the metric system was not in common use by American soldiers. The most accepted theory is the 38 punctures it took to open a can of combat rations, which required some practice for new recruits. Experience with the P-38 gave rise to contests to see who could open their C- Rat faster. Some GIs were so skilled they could open a can of rations in less time than it takes to read this sentence.

For its intended purpose, the P-38 was effective in opening commercial-sized No. 2 cans but difficult to use on larger food containers. Group-sized rations given to troops in field kitchens required the Type II pocket can opener called the P-51, which was a larger version of the P-38 measuring two inches in length or 51mm. The extra half-inch gave the user better leverage and required less thumb pressure to open bulk rations. Produced in far fewer numbers than its P-38 counterpart, the P-51 was less familiar to soldiers but exact in design and use. The origin of its name is also uncertain, and its shared designation with the North American P- 51 Mustang fighter plane is coincidental since the can opener was not commonly used in the field until the late 1950s, nearly a decade after the U.S. Air Force withdrew the legendary air- craft from combat duty. Most likely the name was derived because of the 51 punctures needed to open large canned rations.

Retired After Nearly 40 Years of Use

The end run of the GI Pocket Can Opener came suddenly in the early 1980s when the Army declared C-Rations obsolete and began to manufacture the Meal, Ready to Eat (MRE), which are easy-open food pouches made of aluminum foil and plastic laminate still in use today. U.S. veterans who last opened combat rations with a P-38 are now aged 50 and older, and for many of them the can opener is a fond connection to their time in the service. No one could have foreseen or predicted such an attraction between GIs and the one-cent gadget, nor the bond it created between people and nations during the Cold War.

In 1986 a couple from Czechoslovakia sent a letter to the American Embassy in Prague with something special inside—a P-38. They hoped the embassy staff could locate and thank the manufacturer of their dependable can opener marked U.S. SPEAKER that served them faithfully for four decades. Ludmila and Jiri Novak found the P-38 inside a food pack- age from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), which helped people after World War II with food, clothing, and other basic necessities in countries suffering from starvation, dislocation, and political chaos. Their missive explained how the P-38 long symbolized to them the tremendous sacrifice made by the United States to res- cue their country from Nazi tyranny.

“In 1945 we received two of these can openers from UNRRA relief parcels which your country used to send to Europe to help overcome shortages after World War II. We have used these two can openers for the entire duration of our marriage, even though we tried to replace them with new ones several times. You can just imagine the number of cans of all types which we have opened for these 40 years, without a single problem. New openers did not last too long, they worked only a few times, but the UNRRA openers still work like new. We are sending you one of them in order to prove what we are saying and for the possible identification of a manufacturer so that you might thank them on our behalf. Every time we use the can opener we think about the unselfish assistance of America during and after WWII when in addition to arming the world against Fascism, she lost a large number of her sons, sons who lost their lives fighting for our freedom. We can never forget all these things.”

The Speaker Corp. manufactured its last high-volume order of one million P-38s in the 1990s for a supplier of outdoor equipment, ending 50 years of production by the first and longest maker of the unheralded Army gadget that could do nothing wrong. The company still has some 50,000 can openers in stock that are stored in cardboard boxes, 500 items per box, at its facility in Wisconsin and are parceled out when a veterans group or similar endeavor makes inquiry.

P-38s can readily be found at Army surplus stores and elsewhere, but caveat emptor should be noted. Do not expect a sanitized envelope or plan to spend a penny. They cost about a dollar today.

Nice story. In the Philippines we used to have ots of these can openers due to the GI’s stationed here in 70’s to 80’s. I often used it when I was a boy scout camping.

Still got my P-38 on my key chain. Never know when I might need it!

I HAVE HAD MY P 38 SINCE l WAS DRAFTED 20 JAN 1969 I GOT IT AT FORT KNOX KY. IT STAYED WITH ME DURNING MY 13 MONTHS IN VIETNAM AND I USED MANY TIMES FOR ALL KIND OF THINGS LIKE CUTTING STRINGS ON PACKAGES CUTTING BANDS ON BOXS CUTTING PATCHES AND STRIPS OFF UNIFORMS MOST OF THE TIME I USED IT AS SCREW DRIVER TO OPEN DOORS AND PANNELS ON MY HELOCOPTER IT WAS THE MOST USEFUL TOOL I HAD IN

THE ARMY. MY P 38 WAS MADE BY US MALLIM SHELBY O. AND 2 OTHER’S MADE BY US SHELBY CORP THE FIRST ONE I OWNED IT FOR THE PAST 53 YEARS