By Joseph Connor, Jr.

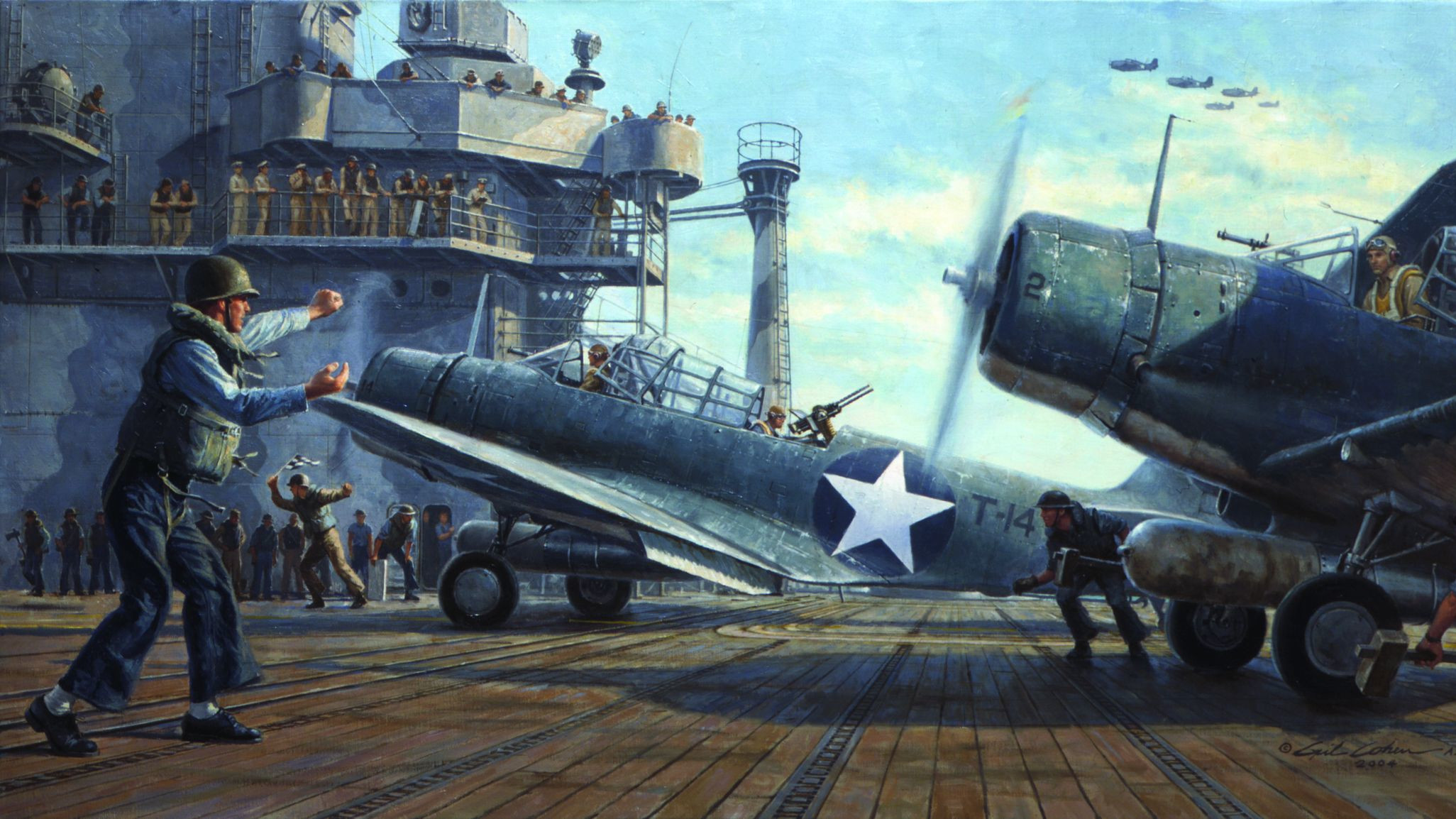

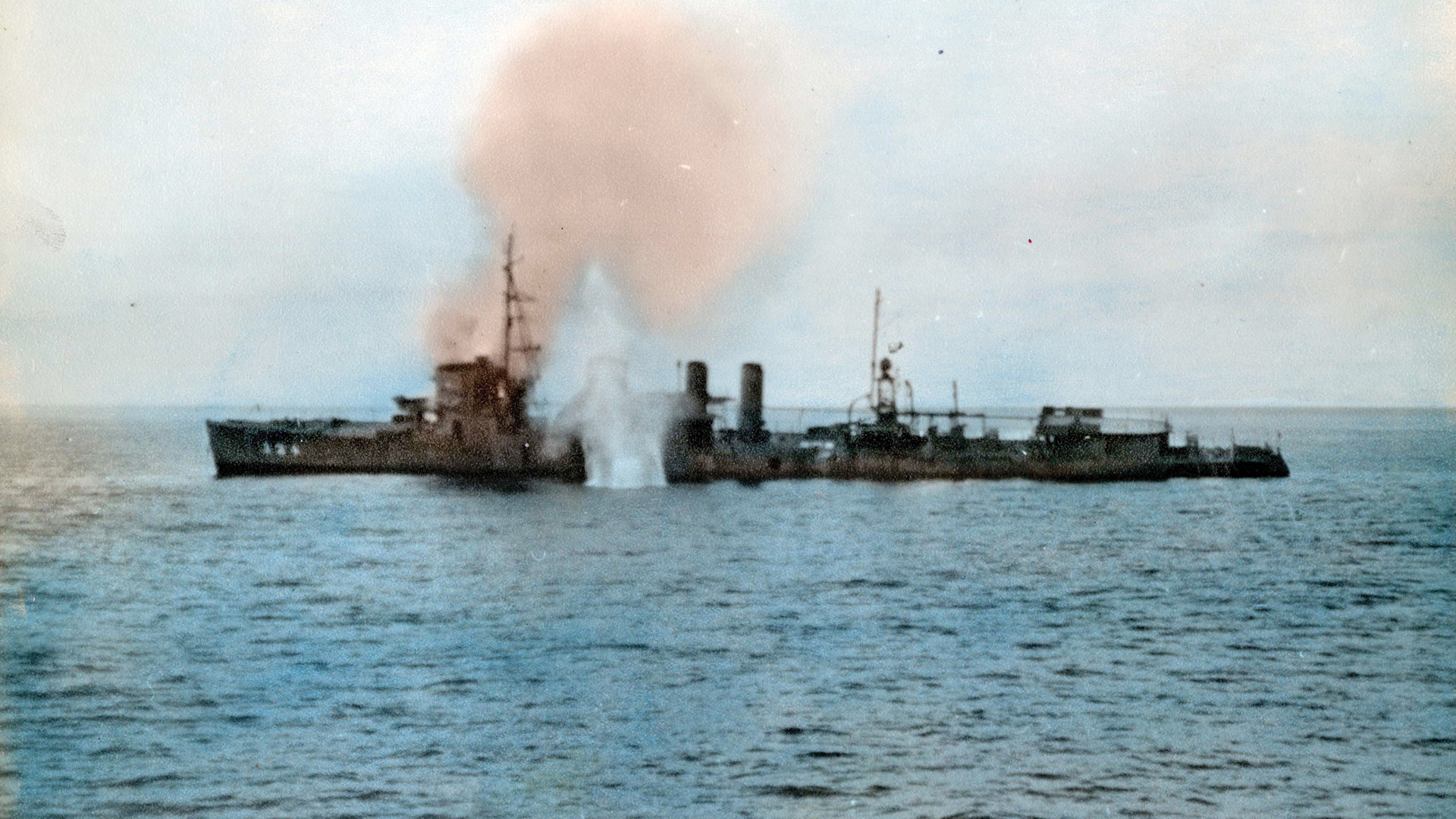

When the destroyer USS Reuben James (DD-245) was assigned to convoy duty in the North Atlantic in the autumn of 1941, its crew had a sense of foreboding and feared the worst. Germany and Great Britain had been at war for two years. The United States was still neutral, at least officially, but neutrality offered little solace—or protection. Deadly German U-boats were prowling the North Atlantic and feasting on Allied shipping. Convoy duty was hazardous and becoming more so by the day.

Reuben James is a name rich in Navy lore. On February 16, 1804, James, a boatswain’s mate, stood on the deck of the USS Philadelphia in Tripoli as Barbary pirates struck.

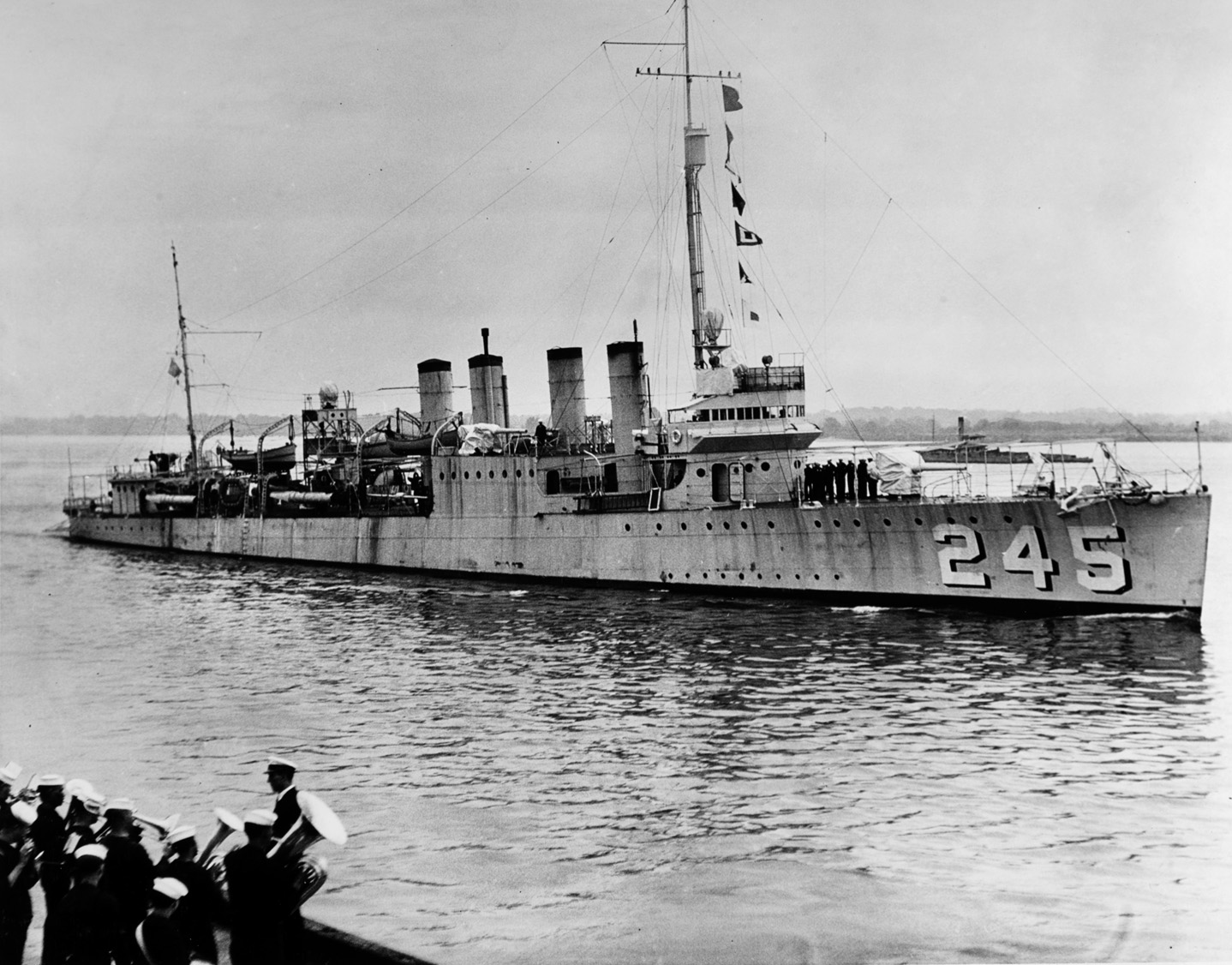

When a sword-wielding pirate attacked Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, James is said to have jumped in front of Decatur and taken the blow meant for him. The ship named for James, the USS Reuben James, was a four-stack destroyer, commissioned in 1920. She was 314 feet long, 30 feet in the beam, and capable of speeds of up to 33 knots. She was armed with four 4-inch guns in her main battery, torpedo tubes, depth charges, and numerous antiaircraft weapons. To her crew, she was affectionately known as “Ol’ Rube.”

Although the United States was still offi- cially neutral, Congress had enacted the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941 to help Great Britain survive. The act permitted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sell, lend, or lease munitions, aircraft, weapons, and military supplies to “the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.” Great Britain was one of those countries.

My two Uncles died on board when the ship was sunk. Corbin Dyson and Charles Harris.

My grandfather Frank Towers died on this ship, he was a policeman in Gadsden , Alabama

My great uncle Albert Mondoux died on this ship.

My great uncle Elmer Rayhill died on the USS Reuben James.

My Uncle Edgar W. Musselwhite perished on the USS Reuban James.

My uncle, Kenneth Neely, only 18, died aboard this ship. My father, Daniel Neely, was on the Simpson, who went through the waters shortly after/-not knowing if his baby brother was dead or alive.

My uncle, Lawrence Sills Jr., of Jackson MS was a survivor with minor injuries. He returned to duty after a brief leave and served for the remainder of WWII.