By William E. Welsh

Thick black smoke rose skyward from burning villages on the southern frontier of the Hungarian Kingdom in the spring of 1395. On a sweeping raid that left seven towns and villages destroyed, fast-riding bands of Ottoman brigands swept into southern Hungary and adjacent lands. Carrying off the few valuables possessed by the Orthodox Slavs, as well as prisoners, the raiders returned to the safety of their strongholds on the south bank of the Danube River.

The Muslim marauders had left the Slavs they encountered with a renewed sense of dread and terror. When King Sigismund of Hungary learned of the Turks’ latest depredations, he redoubled his efforts to get military assistance from Latin Europe against land-hungry Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I. The Ottomans’ continual raids had played a key role in undermining the stability of Bulgaria and Serbia over the past two decades, reducing them to vassal states, and Sigismund had no intention of leaving his kingdom open to similar ruinous consequences.

The Hungarian king knew full well that the Ottomans’ steady march of conquest north through the Balkans was a dagger pointed at the heart of his vulnerable realm. A weak response would send no clear message to Bayezid. What was needed was a massive show of force that would drive the Ottomans back to Adrianople and, just possibly, out of Europe altogether. Sigismund had appealed to the kings of England and France, as well as the Pope in Rome. They heard his desperate plea for help, and they responded favorably by organizing a crusade specifically directed against the seemingly unstoppable Ottomans.

Pope Clement IV tried in the 1340s to get the kings of France and England to end their war against each other and focus instead on the Ottoman threat. But the two kingdoms were so deeply embroiled in a war against each other at the time that his plea fell on deaf ears. But by 1390 both King Richard II of England and Charles VI of France were eager to establish a truce and proved agreeable to the idea of a religious crusade.

In the spring of 1394, Duke Philip of Burgundy sent a delegation to meet with King Sigismund of Hungary on the matter. Fortunately for Sigismund, his generally unruly barons set aside their objections to his method of rule so that the kingdom could unite against the external threat. Shortly afterward, Pope Boniface X in Rome proclaimed a crusade in a bull issued on June 3, 1394, and again in a second bull issued in October.

The Hungarians and Franco-Burgundians did not hammer out the specifics of the Crusade until May 1395. By August that year the Hungarians believed an Ottoman invasion was imminent. They told the French that Sultan Bayezid planned a full-scale invasion of their kingdom in an effort to force upon it a vassal arrangement similar to that imposed on the Serbs and Bulgarians.

The Crusaders agreed to assemble in Buda, Hungary. Forces from far-flung parts of the Holy Roman Empire would either join the Crusaders en route or rendezvous in Buda. Sigismund favored a defensive campaign. In theory it sounded good, but from a practical standpoint it would not have worked. First, it would have been difficult to supply such an army over a long period. Second, there was no guarantee that Bayezid would oblige the Hungarians and their allies and attack them so far from his primary base at Adrianople. Instead, the Crusaders would march south along the Danube seeking battle with the Ottomans. It was not a crusade to the Holy Land, but rather a crusade to rid the Balkans of the Ottomans.

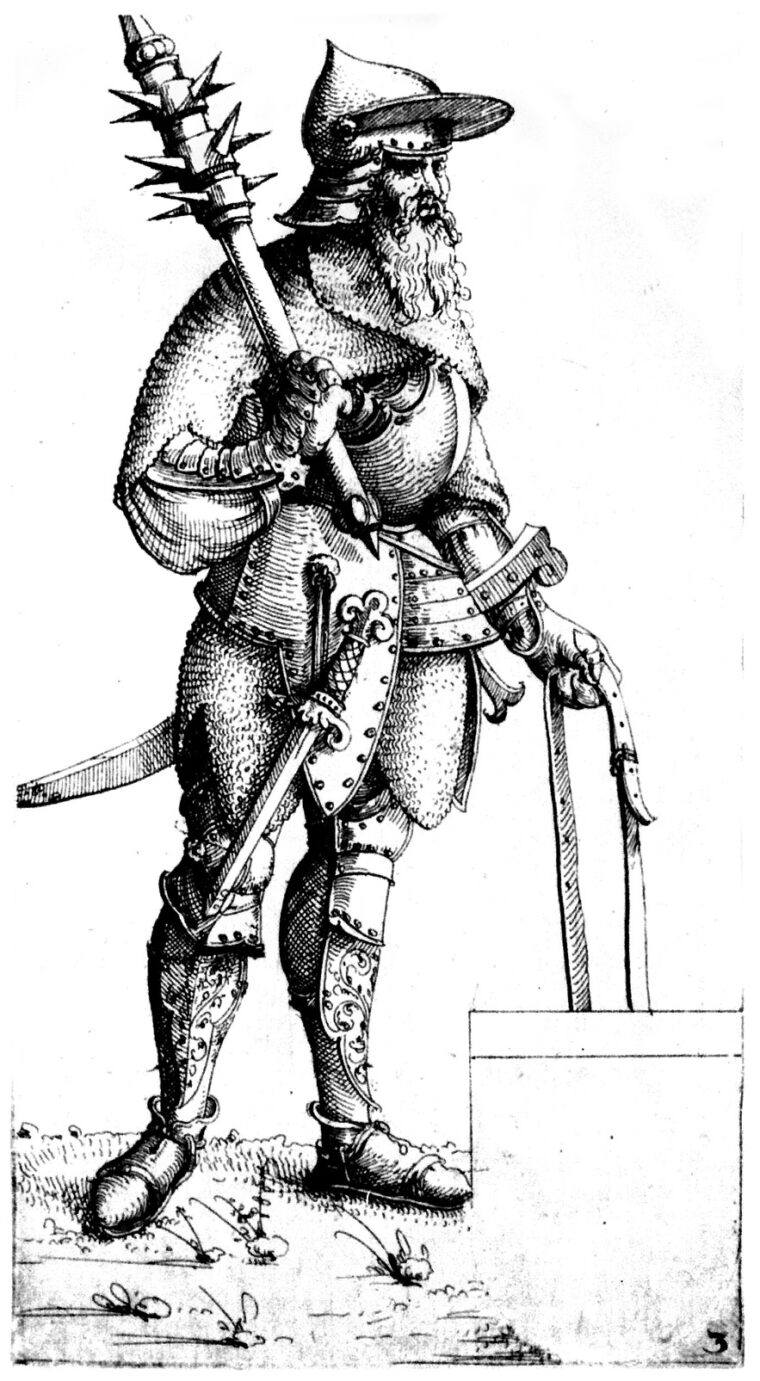

The crusading army ultimately would total 16,000 men. Of this total, approximately 4,000 were heavy cavalry, 5,000 light cavalry, and 2,000 archers. The remaining 5,000 men were Wallachian cavalry led by Mircea the Elder, who remained a vassal of Hungary. The heavy cavalry were predominantly Franco-Burgundian and Hungarian. The retinue of Count John of Nevers, the leader of the Franco-Burgundian complement, was composed of 150 knights. The mounted light cavalry were Hungarian crossbowmen or bowmen, who fired a Turkish bow with three fingers. The infantry were Genoese and Lombard crossbowmen and also German foot soldiers.

The two opponents were nearly evenly matched. Bayezid scrambled throughout the summer of 1396 to raise an army large enough to meet the Latin Crusaders in battle. Ultimately his army included 10,000 Turks and 5,000 Serbian heavy and light cavalry under Prince Stefan Lazarevic. Although the exact numbers of each type of Ottoman warrior in Bayezid’s army are not known, it included three types of cavalry: kapikulu, sipahis, and akinjis. The kapikulu were Bayezid’s household troops and were held in reserve. The sipahis were provincial cavalry of either Anatolian (Asian) or Rumelian (European) origin. The akinjis were light cavalry armed with Turkish bow and sword who functioned as skirmishers. The heavier kapikulu and sipahis were armed with lance, sword, and bow. Except for the kapikulu, the Ottoman cavalry was not as well armored as the Crusader cavalry. Importantly, the lightweight Turkish arrows were not capable of penetrating the mail worn by the Crusader cavalry.

As planned, the Franco-Burgundian army departed Dijon, France, on April 20. Nevers joined the army at Montbeliard as it passed through French-Comte. Nevers led the army east to Regensburg, where it paused to wait for German contingents arriving from the north and for supply boats to be provisioned. The Franco-Burgundian army did not arrive in Vienna until May 24. During this time, Sir Enguerrand de Coucy VII had marched separately through northern Italy to gather Lombard and Genoan troops. In late July the Franco-Burgundians arrived in Buda, where they rendezvoused with de Coucy, Bohemians, Poles, and Sigismund’s Hungarian army.

In mid-August the main Crusader army started south toward Orsova on the Hungarian frontier. Due west, 70 riverboats navigated the Danube in support of the land army. Meanwhile, Venetian Admiral Thomas Mocenigo departed Venice at the head of a Venetian fleet bound for Rhodes. On August 29 the 44 ships that made up the Venetian-Hospitaller fleet sailed for the Black Sea.

Nicholas de Gara, Constable of Hungary, led the vanguard of the Crusader main army, which consisted of some of the Hungarian troops and the German troops. The Franco-Burgundian nobles and their troops formed the main guard. Sigismund led the rear guard with the remainder of the Hungarians. During the last week of August, the Crusaders reached Orsova, where the Danube flows through a limestone gorge known as the Iron Gates. Because of a shortage of large boats to ferry the troops across the wide river, it took the commanders eight days to get their troops across to the south bank. Once across the river, the Crusaders moved quickly against the fortress of Vidin. Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Sratsimir surrendered the 200-man Ottoman garrison to the Crusaders, who promptly executed the Turks. Next, the Crusaders entered Ottoman territory and sacked the stronghold of Orjahova.

After mopping up at Orjahova, the Crusaders continued east along the south bank of the Danube toward Nicopolis. Nicopolis occupied a strategically important location on the lower Danube and was situated near a crossing of the mile-wide river. It served as a base for Ottoman forces conducting offensive operations into southern Hungary and Wallachia.

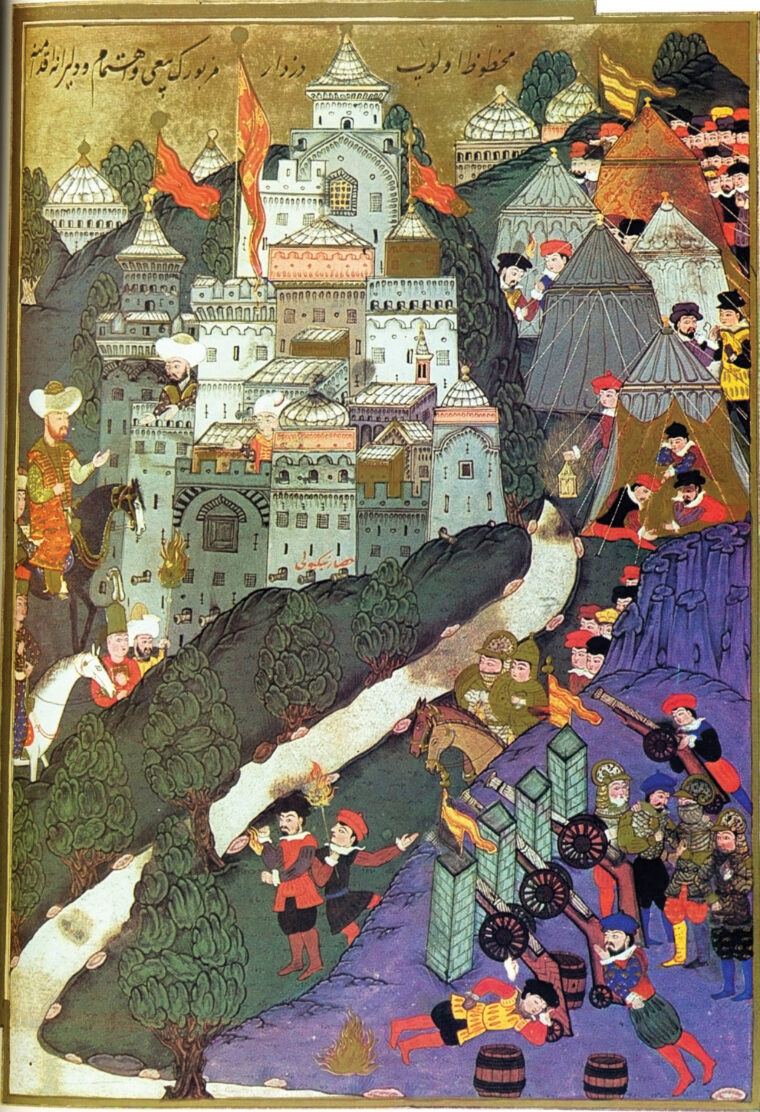

The fortress at Nicopolis consisted of two walled towns in close proximity. The larger citadel on a hilltop afforded a commanding view of the approaches from east and west. A smaller fortress was situated directly below it to the south. Bayezid had entrusted its defense to a stalwart Turkish governor, Dogan Bey, and given him additional troops to resist Crusader thrusts until the main Ottoman army arrived from Constantinople.

The Venetian-Hospitaller fleet arrived on the Danube from the Black Sea and anchored near the Ottoman-held citadel on September 10. Two days later the Crusader main army arrived and invested the stronghold. The Crusaders lacked siege engines with which to soften the walls and terrify the garrison. In the week following the Crusaders’ arrival, the Hungarians, who bivouacked on the west side of the fortress, dug mines for the purpose of bringing down a section of the wall by detonating explosives under it. The Franco-Burgundian troops, who camped on the east side where the ground was less steep, cut trees from nearby forests to build scaling ladders. The lack of siege engines significantly hampered efforts to capture the strong citadel. Neither siege method produced any results.

Bayezid had moved rapidly to field an army capable of meeting the Crusaders in battle. Ottoman forces assembled in Constantinople throughout August and at points designated for assembly on Bayezid’s expected route north to the Danube valley. Bayezid ordered Stefan Lazarevic to rendezvous with him at Tarnovo on the north side of the Balkan Mountains. As the Crusaders fought their way east along the Danube toward Nicopolis, Bayezid’s army departed Constantinople.

Bayezid’s field army included all of the administrative functions of the palace. The sultan’s army comprised the troops who had been besieging Constantinople and Anatolian and Rumelian contingents. It initially marched northwest from Adrianople along the Maritsa River and then turned north to Kazanlak. The Serbians preceded the sultan’s army through the Shipka Pass in the Balkan Mountains. The long columns of Bayezid’s army with its moon-adorned banners tramped through the same mountain pass on September 20. The Ottoman-Serbian army was 116 kilometers to the north, which the Ottoman army could reach in just two days by forced marches. Hungarian scouts under the command of John of Maroth, Viceroy of Belgrade, reported the arrival of the Ottoman main army.

French chroniclers Jean de Wavrin and Jean Froissart describe in detail a preliminary clash that occurred on September 24 between French and Turkish scouting parties. When informed of the arrival of the Ottoman host at Tarnovo, de Coucy assembled 900 lance-wielding knights and mounted crossbowmen to reconnoiter the enemy. Upon spying a reconnaissance party of Turkish akinjis, which belonged to Gazi Evrenos Bey’s command, de Coucy ordered 800 of his force to conceal itself. The other 100 “that were best horsed,” in Froissart’s words, baited the enemy into pursuing it. The Turks took the bait, and those concealed in ambush fell upon them. The French inflicted severe casualties on the Turks before returning to camp, according to the French chroniclers.

Bayezid’s main army took up its position for battle that same day. South of the Nicopolis citadel the ground gradually rose so that the hills, which were dotted with woods, had a commanding view of the river valley to the north. Instead of attacking the Crusaders, he established a strong defensive position on one of the hillsides and waited. He preferred to fight a defensive battle, and he fully expected that the aggressive Crusaders would oblige him. He chose his ground beautifully. The first line of his defense was on the slope of a hill above a dry stream bed. His left flank rested on woods, and his right flank on rough terrain unsuitable for cavalry operations.

While Bayezid was deploying his army for battle on September 24, the Crusaders executed the prisoners taken from Orjahova. The Crusaders did this because they feared that when they marched south to attack Bayezid’s army the Ottoman garrison at Nicopolis might be strong enough to free the lightly guarded prisoners.

Borrowing heavily from Mamluk field tactics, which called for constructing field works consisting of a ditch and palisade to thwart enemy cavalry, Bayezid put his troops to work immediately. Rather than building a palisade, he ordered them to construct a hedge of sharpened stakes five meters deep behind the berm that would be created by the excavated dirt from the ditch. The stakes, which were to be angled forward, were planted at the height of a horse’s belly to break up a cavalry charge. The Crusader cavalry would be slowed not only by having to attack uphill, but also by having to find its way through the sharpened stakes. The Ottoman akinjis would be stationed at various points between Bayezid’s front line and Nicopolis to harass the advance of the Crusaders.

Dismounted infantry known as azabs were stationed directly behind the stakes. The azabs were armed with composite bows, which they used as their primary weapon. They also had swords and axes for hand-to-hand fighting. Stationed a short distance behind the azabs were cavalry known as sipahis. The Rumelian sipahis constituted the right wing, and the Anatolian sipahis made up the left wing. Each division of sipahis was commanded by one of Bayezid’s sons. Suleyman Celebi led the Rumelians, and Mustafa Celebi led the Anatolians.

Bayezid placed his reserve troops, composed of the kapikulu and also Janissaries, on the reverse slope of the hill. Although this may have been a deliberate effort to deceive the Crusaders into believing he had fewer troops than he actually had, it might have been because there was no space for them on the forward slope behind the sipahis. The sultan’s field headquarters, marked by a white banner with gold lettering known as the Ak Sancak, also was located on the reverse slope. The Serbs also were stationed in the valley behind the Ottoman front line.

In a council of war held the evening of September 24, Sigismund suggested that the Crusaders send the Wallachians and Transylvanians to drive off the akinjis the following morning and probe the enemy defenses. He suggested that the Hungarians and Germans form the second rank and the Franco-Burgundians the third rank. Sigismund’s logic was that the central and eastern Europeans had experience fighting the Ottomans and would know how to crack their line. For example, he planned to use bowmen to soften up the enemy before the heavy cavalry attacked.

De Coucy supported Sigismund, but Nevers and Philippe d’Artois, Constable of France, were insulted by the notion that they should follow “peasants” into battle for they believed that the Wallachians, Transylvanians, and some of the Hungarians and Germans were not equal to them in stature. “To take up the rear is to dishonor us and to expose us to the contempt of all,” said Artois. He added that Sigismund was attempting to “gain all the honor of the day” for himself should the Hungarians dislodge the Turks and drive them from the field. The following morning, Sigismund reluctantly agreed to allow the Franco-Burgundian troops to lead the attack.

On the morning of September 25, the Crusaders prepared for battle. Many of the Franco-Burgundian knights wore expensive harnesses. “Every knight of France was in his coat armor, so that every man seemed to be a king they were so richly appareled,” wrote Froissart.

When the Crusaders began the short advance south to assail the Ottoman position, the Franco-Burgundian heavy cavalry formed the vanguard. The main guard that followed was composed of Hungarian and German cavalry. Guarding the Crusader right flank were Steven Lackovic’s Transylvanians, and protecting the Crusader left flank were Mircea the Elder’s Wallachians. During their advance toward the wooded hills to the south the Crusaders were harassed by akinjis, who shot arrows at them.

The vanguard passed through a thin belt of woods and emerged onto the north slope of a ravine. To their front the Crusaders saw a valley with a dry streambed at the base. Halfway up the steep hill on the opposite side of the valley were the Ottomans. The Crusaders surveyed the line and saw infantry wearing conical-shaped headgear with armored cavalry behind them near the crest of the hill. On the opposite side of the hill, the Turks were undoubtedly dazzled by colorful banners and gleaming armor worn by the Crusaders that flashed in the sunlight.

Eager for blood, the Franco-Burgundians began a steady walk down the hill. The akinjis withdrew slowly in front of them continuing to shower them with arrows. As the Crusader knights and squires crossed the valley and rode uphill, akinjis peeled off to the left and right and took refuge behind the azabs. As the Crusader horses moved uphill, the akinjis withdrew and a fresh storm of arrows fired by the azabs zipped through the air toward the attackers. The lightweight arrows used by the Turks did not inflict the desired casualties on the Crusaders because of the sturdy hauberks they wore; nevertheless, the storm of arrows was frightening. “Hail nor rain does not come down in closer shower than did their shafts,” wrote Boucicaut. For their part, the Turks were stunned that their arrows produced so few casualties among the Crusaders clad in what the Turks called “blue iron.”

When the Franco-Burgundian cavalry observed the akinjis withdraw, they immediately charged. This was because they believed the Turkish cavalry was in full retreat and that the Turkish army already might be on the verge of breaking simply by anticipating the consequences of the Crusader charge. While the Turks were not purposely conducting a feigned retreat, the withdrawal of the akinjis lured the Franco-Burgundian vanguard into a premature attack before the Hungarians had closed the wide gap that existed between the vanguard and main guard.

French and Burgundian horsemen, some of whom deliberately sprang from their horses and others who already had been unhorsed, worked together to pull up stakes and create a gap wide enough for 20 men abreast to pass through the rows of stakes. The azabs attacked the dismounted Crusaders, and hand-to-hand fighting became general as the Crusaders fought to smash through the first line of the Ottoman defense. Swordsmen on both sides fought with abandon. Orders were shouted on both sides, and screams of agony from the wounded and dying could be heard above the clang of steel as the fighting grew in intensity until the roar of warfare filled the narrow valley. After a short time, the Franco-Burgundian cavalry succeeded in smashing through the center of the Ottoman line. In response, the azabs pulled back to the right and left and fired into the flanks of the Crusader cavalry.

De Coucy and Jean de Vienne, Admiral of France, who were in the forefront of the fighting, shouted to those around them to wait for the Hungarians to reinforce them, but many of the young knights and squires eager for personal glory disobeyed their orders and continued uphill. Unable to stop them, the more experienced knights joined what became a second charge against the Ottoman sipahis. Fighting between the cavalry of both sides occurred near the crest of the hill.

Realizing the Crusader cavalry were more resilient than they were because of their sturdy armor, the Ottoman sipahis focused on trying to charge their opponents in the flank as they pushed uphill. In a valiant and often suicidal move, the dismounted Crusaders attempted to stab the unarmored Ottoman horses with their swords or daggers to unhorse their riders. The Crusaders who were still mounted charged toward the crest of the hill a third time, but they never reached their objective. By then half of the vanguard was unhorsed and fighting dismounted. The Hungarians and Germans were nowhere to be seen behind them.

Suddenly trumpets blared and cymbals crashed from the other side of the hill occupied by the Turks. Fresh Ottoman cavalry thundered over the crest. Bayezid had sensed the battle hung in the balance and made the fateful decision to send the kapikulu into the battle. The fresh Ottoman cavalry crashed like a monster wave into the enemy. The Crusader vanguard, which had suffered significant losses by then, was outnumbered. The Ottoman troops already engaged rallied when the kapikulu entered the battle and pressed their attack anew against the Crusaders. The kapikulu, who were much better armored than the sipahis, fought with abandon. They battered their opponents with heavy maces. The French and Burgundians fought on against frightful odds. The Ottoman cavalry eventually surrounded the Crusader vanguard, cutting off their path of retreat. “The Turks are behind us!” shouted some of the Crusaders. The kapikulu focused on capturing the banners carried by companions of the French and Burgundian nobles who led the vanguard.

The French sources are full of accounts that record the deeds of valor performed by their nobles as they tried to stave off defeat. De Vienne’s companions were responsible for the Banner of the Virgin Mary. When the last of his companions had been slain, de Vienne raised the banner aloft for the last time. Fighting with the banner in one hand and his sword in the other, he was slain by the Turks. As for de Coucy, the Turks clubbed him, presumably with maces, on his helmet, beating him to the ground in the process. Although heavily bruised, he would survive. Boucicaut was said to have “rushed into the thickest ranks of the enemy and cut passages for himself like a mower in a meadow.” He also would survive the ordeal. Eventually, the Ottomans surrounded Nevers, at which point he surrendered. Following his lead, so did the other French and Burgundian soldiers. The French would come to regard the humiliating defeat as akin to the disaster Charlemagne suffered at Roncesvalles. The Turks herded them together to await Bayezid’s orders regarding their fate.

When the Hungarian Army emerged from the thin belt of wood about an hour after the Crusader vanguard had started fighting, it was too late to save them. Nevertheless, Sigismund ordered an attack against the reformed Ottoman infantry on the opposite slope. The Hungarians, Hospitallers, and Germans had broken through the infantry and were fighting the sipahis when a fresh column of enemy cavalry struck them in the right flank. These were the Serbs. They were well armored and capable of fighting the Hungarian heavy cavalry on equal terms. The Serb cavalry, which had been concealed on the reverse slope of the hill, had somehow managed to work its way through the woods and fall upon the Hungarians.

Sigismund believed the day was lost and began a headlong flight north in he abandoned the hapless French and Burgundians to what would be a terrible fate. The fleeing Hungarians and Germans were pursued hotly by the Turkish and Serb cavalry. “Great murder there was; for in flying they were chased, and so slain,” wrote Froissart. As they made their way toward Nicopolis as quickly as possible, the Hungarians found that the Transylvanian and Wallachian cavalry, who had no love for Sigismund, had already exited the battlefield. The mindset of their respective commanders was to save their men for future battles against the Ottomans.

The retreating knights, squires, and common soldiers all rushed toward the Danube. Each hoped to reach the safety of one of the Venetian or Hospitaller boats anchored near the shore. A battalion of 200 crossbowmen covered the evacuation and eventually was wiped out by the Turks. Sigismund waded into the water on horseback and was fortunate enough to climb aboard a small boat along with seven of his companions. As for the other Crusaders, many of whom were in a state of panic, most of them were not evacuated because the boats could only accommodate a small number of men. Thus, the vast majority of the Hungarians and Germans either drowned in the Danube or were slain by the Turks on the river bank.

As for the French and Burgundians, Bayezid ordered the majority of them executed in retaliation for the Crusaders’ execution of garrison troops and prisoners from the Ottoman-held Danube fortresses. In total, the Ottomans executed approximately 3,000 prisoners. Nevers, Artois, Coucy, and a few hundred others were taken into captivity to be ransomed, but some would die in captivity. Sigismund blamed the French for the loss. “We lost the day by the pride and vanity of these French,” he purportedly said.

Join The Conversation

Comments