By Pat Mctaggart

During the last half of 1944, the Wehrmacht in the east had been forced to cede just about everything it had conquered since the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union in June 1941. Suffering appalling losses, German forces were compelled to abandon the Ukraine and most of the land in the Baltic States. By the end of the year, Soviet troops had knocked Bulgaria and Romania out of the war, and Finland had also sued for peace. The Soviets had also occupied a large area of Hungary and Poland and were standing inside the border of East Prussia.

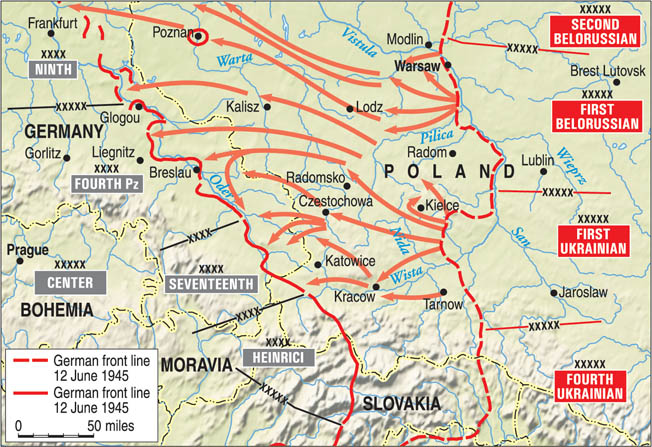

In the sector occupied by General Josef Harpe’s Army Group A, German troops manned fortifications behind the Vistula River in Poland. However, the Vistula line was not impregnable. Before ceasing operations to resupply, the Soviets had seized three bridgeheads on the west bank of the river.

About 36 kilometers south of Warsaw, Marshal Georgii Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front occupied a bridgehead that was about 10 kilometers deep and 12 to 16 kilometers wide near the town of Magnuszen. A second bridgehead about 35 kilometers to the southeast was centered near Pulawy and measured about 10 kilometers deep by 18 kilometers wide.

The bridgehead occupied by elements of Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was by far the largest. Located about 130 kilometers southeast of Warsaw in the Sandomierz area, it measured about 60 kilometers wide and was about 42 kilometers at its greatest depth. It was from this bridgehead that Konev planned to continue his offensive once the order was given.

Born into a peasant family on December 28, 1897, Konev was one of the best commanders the Soviets had. Called into the Army in April 1916, he experienced little fighting before the czar’s forces disintegrated. During the Russian Civil War he saw action on the Eastern Front, becoming Commissar of the 17th Maritime Corps. He attended the Frunze Military Academy and rose through the ranks to command a regiment, division, and the 57th Special Corps in Mongolia and eventually the 2nd Separate Red Banner Army.

By June 1941, Konev was commanding the 19th Army and had risen to the rank of colonel general while fighting the bloody battles in the opening stages of the war. In September 1941, he was appointed commander of the Western Front. Within a month the front was practically destroyed as five of its armies were annihilated in the Vyazma encirclement. It was only through the intervention of Zhukov that Konev was saved from being executed.

As Soviet fortunes turned during the middle part of the war, Konev commanded a succession of fronts that helped drive the Germans from the Motherland. After the destruction of the Korsun-Cherkassy Pocket in early 1944, he was promoted to the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union. Now, in the opening days of 1945, he was ready to strike again.

Both Konev and Zhukov had similar orders. They were to smash the German forces along the Vistula and drive to the banks of the Oder River in preparation for the final assault on Berlin. In the process, Zhukov would capture the key cities of Warsaw, Radom, Lodz, and Poznan. Konev’s route would take him through Kielce, Czestochowa, Krakow, and Katowice and into the heartland of Silesia’s industrial area.

General Fritz-Hubert Gräser would be Konev’s main opponent as he covered the 500-600 kilometers from the Vistula to the Oder. Gräser was born in Frankfurt on March 11, 1888, and entered the Kaiser’s army as an officer candidate in February 1907. He fought in World War I and retired from the Army in October 1933.

Rejoining the German Army in October 1935, he was promoted to colonel in October 1938 and led Infantry Regiment 29 of the 3rd Infantry (later Panzergrenadier) Division (PGD) during the opening phase of the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Gräser was wounded while commanding the regiment, and after his recovery he took command of the division in March 1943. He commanded the XXIV Panzer Corps in 1944 and took over as commander of the 4th Panzer Army in September of that year.

Although designated as a panzer army, the 4th was woefully short of armor. General Johannes Block’s LVI Panzer Corps consisted of two German (17th and 214th) and one Hungarian (5th Reserve) infantry divisions. General Hermann Recknagel’s XLII Army Corps had four infantry divisions (72nd, 88th, 291st, and 342nd), and General Maximilian Freiherr von Edelsheim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps had three infantry divisions (68th, 168th, and 304th).

The Army Reserve consisted of General Walther Nehring’s XXIV Panzer Corps, which had two panzer divisions—the 16th and 17th. Brig. Gen. Dietrich von Müller’s 16th had a depleted strength of nine obsolete PzKpfw. IIIs, 13 outgunned PzKpfw. IVs, and 62 PzKpfw. V Panther tanks. Colonel Albert Brux’s 17th had a strength of 65 PzKpfw. IVs and 19 PzKpfw. IV/70 tank destroyers. Most of the crews, however, were hastily trained and would see combat for the first time. Brig. Gen. Karl-Richard Kossmann’s 10th PGD and Brig. Gen. Georg Jauer’s 20th PGD were also in the army’s area of operations.

Terrain was an important factor in the German defense plans. Most of the area that Konev would have to cross was basically flat with few hills or forests. It was excellent tank country. Besides fortifications placed in front of the Sandomierz bridgehead, there were hastily built defenses along the Nida and Pilica Rivers. Behind them, defensive lines ran along the Warta and Notec Rivers with a further line about 120 kilometers to the west. Most of these fortifications were weak, and few were actually manned due to a shortage of troops.

Konev planned to use his extensive mobile forces to make lightning thrusts and seize crossings along all these lines of defense. Engineers would follow closely behind to build bridges across the rivers. Any built-up urban areas would be bypassed if the first attempt to take them failed. Follow-up troops would be used to surround and destroy any of these areas of resistance.

To accomplish his mission Konev had about 1.1 million men, of which about 750,000 were combat troops. German intelligence estimated that three or four Soviet armies occupied the Sandomierz bridgehead. There were actually six and part of another.

The Russians had brought maskirovka (deception) to a new level to fool the Germans. Because of the terrain inside the bridgehead, units and vehicles were cleverly camouflaged and radio traffic was kept at a minimum. New formations were brought across the Vistula only at night, and evidence of road traffic was quickly covered up.

Konev used Lt. Gen. Pavel Poluboiarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps to simulate the existence of two tank armies south of the bridgehead on the eastern side of the river. About 500 dummy tanks were also assembled in the area and were filmed by German air reconnaissance. Fake radio traffic added to the deception. With all these measures, the Germans were partially convinced that an attack would come from the south as well as from the bridgehead.

Inside the bridgehead, Konev had most of Lt. Gen. Vladimir Gluzdovskii’s 6th Army (four rifle divisions) occupying about 40 kilometers of its northern sector. Facing west were Col. Gen. Vasilii Gordov’s 3rd Guards Army (nine infantry divisions, three tank brigades, one motorized rifle brigade, and three assault gun regiments), Lt. Gen. Nikolai Pukhov’s 13th Army (nine rifle divisions, three tank regiments, and four assault gun regiments), and Lt. Gen. Dmitri Leliushenko’s 4th Tank Army (five tank brigades, three mechanized brigades, one motorized rifle brigade, five tank regiments, one assault gun brigade, and four assault gun regiments).

South of those units were Col. Gen. Konstantin Koroteev’s 52nd Army (nine rifle divisions and one tank brigade), Col. Gen. Pavel Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army (seven tank brigades, one tank regiment, five mechanized brigades, one motorized rifle brigade, one assault gun brigade, and six assault gun regiments), and Maj. Gen. Georgii Poluektov’s 5th Guards Army (eight rifle divisions, one airborne rifle division, two tank regiments, and eight assault gun regiments). Konev’s flank was occupied by Col. Gen. Pavel Kurochkin’s 60th Army (nine rifle division). On the eastern bank of the Vistula stood Lt. Gen. Dmitrii Gusev’s 21st Army (nine rifle divisions) and Lt. Gen. Ivan Korovnikov’s 59th Army (seven rifle divisions).

The maskirovka at Sandomierz had been brilliant. The Germans estimated that they were outnumbered by about 3.5 to one, while the actual figure was double that. To combat the tanks of the 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions, the 4th Guards Tank Army had about 800 tanks, while the 3rd Guards Tank Army had about 750. At the focal points of the attack, the Soviets would outnumber the Germans by a ratio of 10-15 to one.

“My husband later told me that our intelligence had totally failed us,” wrote Gräser’s widow, Eldegard, in a 1971 letter to the author. “He knew that he was outnumbered, but he had no idea how really bad it was.”

Konev would be covered by an umbrella from the 2nd Air Army. The 2nd had four bomber, 10 fighter, and four air assault divisions. This massive force would hold what was left of the Luftwaffe at bay—although the weather during most of the operation would make for bad flying conditions—while Konev’s armor pushed forward. Usually the Soviets would use their infantry to breach and widen the enemy line. Armor would then exploit the breaches a day or two later. This time, Konev planned to use most of his armor on day one.

At 0500 on January 12, Konev’s artillery opened fire on von Edelsheim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps. An estimated 420 guns per half kilometer rained hell upon the three divisions of the corps for 45 minutes before the barrage suddenly halted. During the lull, hundreds of Red Army infantry platoons swarmed out of the bridgehead and quickly moved toward the German positions. Their objectives were key positions in the bridgehead perimeter, and most of these were captured from the stunned German survivors.

With the preliminary objectives in hand, Konev’s artillery opened up for another 15 minutes, pounding German secondary positions. On the heels of the barrage the Soviet infantry that had captured the bridgehead defenses moved out again. Other infantry battalions were also sent forward to occupy the previously captured positions.

“All the gunners had to do is shoot straight,” Konev wrote in his memoirs. “And they never failed: not once did they get an alarm signal—‘Stop, you are hitting your own men’—from any of the troops attacking along the entire front.”

Major General Paul Scheuerpflug’s 68th Infantry Division felt the full fury of Poluektov’s 5th Guards Army as the 32nd (Lt. Gen. Aleksandr Rodimstev), 33rd (Lt. Gen. Nikita Lebedenko), and 34th (Maj. Gen. Gleb Baklanov) Guards Rifle Corps drove forward. Scheuerpflug’s left flank was also hit by the 52nd Army’s 73rd (Maj. Gen. Sarko Martirosian) and 78th (Maj. Gen. Georgii Latyshev) Rifle Corps.

To Scheuerpflug’s right, Maj. Gen. Ernst Seiler’s 304th Infantry Division was attacked by Maj. Gen. Petr Tertyshnyi’s 15th Rifle Corps and Maj. Gen. Mikhail Ozimin’s 28th Rifle Corps of the 60th Army. Their job was to drive a wedge between the 4th Panzer Army and General Friedrich Schulz’s 17th Army in preparation for a drive on Krakow. The other division of Edelsheim’s corps, Colonel Maximilian Rosskopf’s 168th, was hit by the 3rd Guards Army’s 21st (Maj. Gen. Aleksei Iamanov) and 76th (Lt. Gen. Mikhail Glukhov) Rifle Corps and the 13th Army’s 102nd (Maj. Gen. Ivan Puzikov) and 27th (Maj. Gen. Filipp Cherokmanov) Rifle Corps.

With such a concentrated force attacking them, the 68th and 168th Infantry Divisions simply disappeared. Scattered groups tried to make their way westward, but for the most part they were overwhelmed by masses of brown-uniformed troops. By the end of the day, most of the regiments in those divisions had been reduced to an understrength battalion or worse. Recknagel’s corps was in much the same position.

Seeing the disintegration of the German lines, Konev unleashed his armored and mechanized forces. The 4th Tank Army and 3rd Guards Tank Army weaved their way through the advancing infantry to spread out ahead of them. This forced Gräser to prematurely commit the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions, as there was little or no resistance from the shattered German infantry. He also ordered Brig. Gen. Hermann Hohn to form his 72nd Infantry Division into three battle groups and move south to hit the flank of the Soviet penetration.

As the panzer divisions began arriving on the scene, they were initially engaged by the advancing Soviet armor. With the inexperience of the panzer crews, the Germans suffered extensive losses. After the first engagements, the Soviets continued to move to the west, bypassing the disorganized German armor. By the end of the first day of battle, the Soviet tank and mechanized forces had penetrated 20-25 kilometers behind the German line with the Red Army infantry about 10-15 kilometers behind them.

The rapid Soviet advance coupled with the devastating artillery barrage totally disrupted the German communications network. “There was total chaos,” Frau Gräser recalled her husband saying. “Most of von Edelsheim’s and Recknagel’s corps were no longer there. The divisions were just gone.”

On the 13th the situation grew even more chaotic for the Germans. The 17th Panzer Division had been bypassed on its northern flank by the 4th Tank Army’s 10th Guards Tank Corps and Maj. Gen. Sergei Pushkarev’s 6th Guards Mechanized Corps. Maj. Gen. Vasilii Novikov’s 6th Guards Tank Corps and Lt. Gen. Ivan Sukhov’s 9th Mechanized Corps bypassed the division’s southern flank. Its position around the town of Chmielnik, about 32 kilometers south of Kielce, was growing more and more hopeless as the infantry of the 13th and 52nd Armies advanced.

A yawning gap of 40-50 kilometers separated the 17th from Sieler’s 304th Infantry Division, the only one of Recknagel’s divisions that showed any form of cohesion in retreating from the Soviet onslaught. Gräser’s parent headquarters, General Josef Harpe’s Army Group A, was only able to scrape up one regiment of Brig. Gen. Georg Kossmala’s 344th Infantry Division from its reserves to try to close the gap. It was soon pushed aside by Lebedenko’s 33rd and Baklanov’s 34th Guards Rifle Corps.

Harpe also ordered a combat group of Jauer’s 20th PGD to aid the combat groups of the 72nd Infantry Division. It was stopped cold by Soviet infantry that was following hard on the heels of the 4th Tank Army. The battle groups of the 72nd met the same fate as they ran into the infantry of the 3rd Guards Army.

First Lieutenant Karl Zimmer was the leader of the II/Gren. Rgt. 105 of the 72nd. He recalled the events of the 13th in a 1984 letter to the author:

“We could see the Russians in the distance advancing toward us. Their artillery fire quickly forced us into defensive positions. Our own artillery responded weakly. We met the Russians with defensive fire, but they continued to come at us, pushing us back again and again.”

While Gräser’s troops were fighting for their lives, the Soviets made matters worse on the 14th when Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front burst out of its bridgeheads at Magnuszew and Pulawy after an exceedingly heavy bombardment against the defenses of General Smilo Freiherr von Lüttwitz’s 9th Army. As had happened in Gräser’s sector only two days earlier, the German forces that survived the barrage were thrown back in disarray.

There seemed little the Germans could do to stem the Russian tide. The situation of the 4th Panzer Army grew more critical as Soviet mechanized forces continued to push west. Elements of Maj. Gen. Vasilii Grigorev’s 31st Tank Corps (directly subordinated to the 1st Ukrainian Front) were within 10 kilometers of the Pilica River by the end of the day with largely undefended positions in front of them.

South of Kielce, the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions were almost encircled. “My battalion, with the remaining elements of the 2nd Panzer Battalion/Pz. Rgt. 30, was located about 12-15 kilometers south of Kielce in open terrain,” recalled Major (later colonel in the Bundeswehr) Hans-Günther Liebisch, commander of the I/Pz. Gren. Rgt. 40/17th Pz. Div. “We suffered from heavy attacks from fighter ground attack aircraft, but these were discontinued due to the defensive fire of the mechanized infantry fighting vehicles.”

Konev was also driving on Krakow. His 59th Army, protected on the left by the 60th Army, was bearing down on the city. Von Edelsheim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, consisting of the shattered 68th and 168th Infantry Divisions and the reduced 304th Infantry Division, was transferred to Schulz’s 17th Army. To try to stop the Soviets, Harpe ordered a regimental group of the 10th PGD to take up positions at Walbrom, about 14 kilometers north of Krakow. He also sent Brig. Gen. Karl Arning’s 75th Infantry Division to an area south of Walbrom.

On January 15, the 3rd Guards Tank Army crossed the Pilica River, bypassing the positions of a combat group of the 10th PGD at Koniecpol, about 30 kilometers east of Chestochowa. While the Soviets ferried more troops and supplies across the river, the Germans set up a hasty defensive position in front of the city, using whatever troops were on hand.

North of Krakow, Poluboiarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps, followed by the 59th Army’s 43rd and 115th Rifle Corps, broke through the 75th Infantry Division’s line north of Krakow and continued its drive westward. To counter the advance, Harpe ordered Maj. Gen. Hans Wagner’s 269th Infantry Division into an area about 24 kilometers northwest of Krakow.

Inside the Kielce area the situation was desperate. The 16th Panzer had managed to break clear of the encirclement, but 17th Panzer was still in dire straits. The remaining elements of the division attempted to get out of the cauldron but hit a heavily defended blocking position in the early morning of January 15. Antitank guns raked the Germans, and the few remaining vehicles finally fought their way to meet the rear guard of the 16th Panzer.

“After three days of battle the battalion, together with what remained of other battle groups, particularly the 2nd Panzer Battalion, had broken through several ranks of enveloping enemy elements and had finally made contact with elements of the 16th Panzer,” Liebisch recalled. “No uniform command and control had existed in these operations. The will to break through had induced us to joint action. The 17th Panzer was no longer.”

The survivors of both panzer divisions were reformed into a combat group commanded by General Dietrich von Müller, the commander of the 16th. Soviet units were already inside Kielce, and the city was ablaze in several areas. Combat Group von Müller, unable to stop the Soviet flood, hooked up with some German infantry units and moved westward to attempt to establish a new defensive line.

While Russian troops battled at Kielce, Rybakov’s 3rd Guards Tank Army, supported by the 31st Tank Corps, bore down on Chestochowa. There were a few rear elements on the German side that put up a fight, but there was little real opposition to the Soviet advance.

To the southeast Poluboiarov’s Independent 4th Guards Tank Corps was at the forefront of Korovnikov’s 59th Army as it drove on Krakow. Arning’s 75th Infantry Division put up a desperate fight, but the Soviets pierced its lines in several places, forcing it into a fighting withdrawal. The hard-pressed 17th Army was able to send only a few small units to man positions north of the city, where they were momentarily able to slow the Russians.

In Berlin, the Chief of the General Staff of the Army, General Heinz Guderian, was pleading for more troops to be sent to the Eastern Front. As early as January 9, he had telephoned Hitler’s western headquarters, where Hitler was overseeing the Ardennes Offensive, to make the Führer aware of the tremendous danger poised in the East. After laying out his case for switching troops from the West to the East, Guderian was met with a few seconds of silence.

“The Eastern Front must make do with what it’s got,” Hitler finally responded.

Hitler did, however, order General Dietrich von Saucken’s Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland (GD) to move from its positions in East Prussia south to the Lodz area—a move that infuriated Guderian. The corps was one of the key units in the East Prussian defenses, and its absence would make the dangerous situation in that sector even more perilous. Nevertheless, the corps arrived piecemeal at Lodz and would not be fully organized until the 18th.

By the end of January 16, Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front was encircling Warsaw. Harpe ordered German troops out of the city just before the encirclement was complete, saving most of the XLVI Panzer Corps. The city fell to the Soviets the following day. Radom also fell on the 16th.

Farther south the fighting continued to rage around Kielce. Shattered units hovered around Nehring’s XXIV Panzer Corps. The majority of the units were encircled in an area northwest of the city and had formed hedgehog positions to keep from being overrun. The fighting was savage, but luckily for the Germans most of the Soviet armor and mechanized forces were still pushing westward.

At the end of the day, Novikov’s’s 6th Guards Tank Corps was at the outskirts of Radomsko with Latyshev’s 78th Rifle Corps guarding its southern flank. The 31st Tank Corps, with the accompanying 33rd and 34th Guards Rifle Corps, was also within a few kilometers of Chestochowa, and Soviet artillery was already shelling German positions east of the city.

Warsaw fell to Zhukov’s troops on the 17th. As Soviet and Polish forces entered the devastated city, few of its inhabitants were on hand to greet them. It was estimated that of the 1,310,000 people that resided in the city in 1939, fewer than 100,000 were left when it was liberated.

While Zhukov took the glory in taking Warsaw, Konev’s forces continued to batter their way westward. Chestochowa was now encircled and was under attack by Colonel Grigorii Polishchuck’s 9th Guards Airborne Division, Colonel Vladimir Komarov’s 13th Guards Division, and Maj. Gen. Vikentii Skryganov’s 14th Guards Rifle Division. The city would fall later that evening. Meanwhile, the 7th Guards Tank Corps and the 31st Tank Corps had bypassed the city and continued to drive west.

At Krakow, Arning’s 75th Infantry Division was barely hanging on north of the city. The 75th was helped by the arrival of Brig. Gen. Georg Kossmala’s 344th Infantry Division. To counter the Germans’ defense, Poluboiarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps swung southwest around the German line while the 60th Army continued a frontal assault.

In the Kielce sector, the situation became more serious. Nehring’s XXIV Panzer Corps and Recknagel’s XLII Army Corps were surrounded and cut off from each other. They formed “floating pockets” that slowly moved westward, fighting off Russian attacks from all sides. They would eventually link up as they tried to reach the German line.

German 1st Lieutenant Zimmer recalled joining the Nehring pocket: “What was left of my battalion made its way through the [Nehring pocket] line. Some units of the 72nd were still with Recknagel, and some had also made their way here, but we had no cohesion. My battalion was thrown into the line with a unit of the 88th Division on one side and a unit from another division on the other side.”

Nehring was now surrounded by five Russian rifle corps, a cavalry corps, two tank corps, and a mechanized corps. To stay put would mean annihilation, so the pocket continued to move to the west with combat units on the perimeter and service, supply, and medical troops in the middle.

“On the afternoon of the 17th we broke out westward,” Colonel Liebisch recalled. “On the 18th we were fortunate enough to get to an army supply depot where we were able to refuel. After that, we blew up the depot. We formed a moving pocket. How many soldiers were in the pocket I don’t think we will ever be able to find out. There are estimates that more than 100,000 soldiers were in this pocket. The armored personnel carriers of the battalion alone carried at least eight divisional commanders.

One commander was not in that group. The 17th Panzer’s commander, Colonel Brux, was wounded in the Kielce area and was taken prisoner on the 17th. He would not return to Germany until January 1956.

The Soviet advance was going as planned. With the fall of Chestochowa on the evening of the 17th, the infantry could follow the mechanized and armored forces driving toward the Oder.

With little opposition facing them on the ground and no serious threat from the air, Russian supply columns were on the move day and night to keep Konev’s mobile forces going. The tank and mechanized brigades were sometimes operating 50-80 kilometers ahead of the infantry armies, and each of the tank armies required about 300 trucks per day just for fuel supply. Another 300 trucks were required for ammunition. It was truly a tremendous logistics operation.

Although massive fuel dumps were in place at the start of the offensive, the Russians were also able to capture several German dumps as they advanced. Specialists tested the captured fuel to make sure that it had not been sabotaged before it was used by Red Army vehicles. The enemy dumps were important as the front advanced since the supply convoys could only deliver one-third to one-half of the required fuel and ammunition for one day of combat operations. The captured enemy dumps could greatly decrease the time it took for a convoy to reach the front and return.

Food for the troops seems to have been a low priority. Although the Red Army soldiers carried some food, mainly American made Spam, they were expected to live off the land. While liberating Polish towns, cities, and villages, they also liberated anything they could eat, causing even more hardship for the Polish population.

On January 18, German resistance stiffened east of Katowice. To avoid being encircled by the 4th Guards Tank Corps, the units defending positions north of Krakow began withdrawing to the west. Maj. Gen. Friedrich-Carl Rabe von Papenheim’s 97th Jäger (light) Division was filtering units into the line between the positions of the 75th and 712th Infantry Divisions. Elements of Brig. Gen. Hermann von Oppeln-Bronikowski’s 20th Panzer Division were also arriving on the scene.

In addition to these units, five Volkssturm battalions manned defenses about 30 kilometers north of Katowice in a line running from the town of Myszkow to Wozniki. Unlike their counterparts in the West, most of the Volkssturm units in the East put up a decent fight. It was, perhaps, easier to surrender to the Americans or the British than it was to the Red Army, which was seeking revenge for atrocities committed in its own country.

The Volkssturm was made up of young teenagers, old men, and those who were previously deemed unfit for military service. Armed with a hodgepodge of weapons, they were best used in defensive positions rather than for attacking. In many cases they were defending the very towns that they lived in.

Krakow fell to the 60th Army on the 19th. As the Germans had all but abandoned it, the city remained mostly intact, escaping the fate of many other Polish cities that were destroyed by Soviet artillery and air power.

Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army had by now crossed the Prosna River. Its advance elements were less than 60 kilometers from Breslau and the Oder River and were on the border of Middle Silesia. Gräser ordered Maj. Gen. Hans Wagner’s 269th Infantry Division and Maj. Gen. Heinrich Wosch’s 408th Replacement Division to the western bank of the Oder to take up positions near the towns of Picse and Kepno.

The floating pocket of Nehring’s corps, now augmented by the survivors of the LVI Panzer Corps that had been able to fight their way through to Nehring, continued to retreat westward with Jauer’s 20th PGD, along with a few attached battalions, forming the rear guard. With the 3rd Guards Army pressing from the south and east and Maj. Gen. Vladimir Kolpakchi’s 69th Army of Zhukov’s front coming down from the north, the pocket turned to the northwest, hoping to link up with the GD Panzer Corps, which had been pushed out of Lodz and was moving southeast.

There were four rifle corps nipping at Nehring’s heels, and Jauer’s rear guard was hard pressed to slow them down. By January 20, elements of the 17th Panzer were able to cross the Pilica River north of Sulejow. The Soviets reacted by hitting the pocket north of Piotkow, about 15 kilometers north of the crossing. Although it was making progress, the wandering pocket was still more than 70 kilometers from von Saucken’s GD Panzer Corps, which was defending an area around Sieradz.

South of the pocket, Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army had reached the Silesian border. The only thing stopping him from accomplishing his objective of driving on Breslau was the hastily constructed defenses of the 269th and 408th Divisions, which were now augmented by 10 Volkssturm battalions. Inside Breslau itself, a mix of army and Luftwaffe battle groups and Volkssturm battalions numbered only about 18,000 men.

Konev was conscious of the rapid westward movement of Zhukov’s front in the north. There was a rivalry between the two men that was encouraged by Soviet Premier Josef Stalin. Both wanted to capture the prize of Berlin, and the January operation was a giant step toward that goal. Although the armies in the northern sector of his front were almost keeping pace with Zhukov, Konev’s southern armies, particularly the 21st, 59th, and 60th, were running into heavier opposition as more German divisions and combat groups arrived from the south to man the line.

To break the German defenses west of Krakow, Konev ordered Rybalko to stop his westward advance and make a 90-degree turn south to strike the rear of the enemy line. In a matter of hours, Rybalko had Maj. Gen. Sergei Ivanov’s 7th Guards Tank Corps racing south to take up new positions along the Oder River south of Oppeln. Novikov’s 6th Guards Tank Corps was directed to an area east of Oppeln, while Sukhov’s 9th Mechanized Corps guarded the army’s left flank. The infantry of the 52nd Army would soon move forward to fill the void left by Rybalko’s maneuver.

Despite repeated Russian attacks on the 21st, von Saucken’s men held onto their positions in the Sieradz area. They had established a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Warthe (Warta) River around one of the few bridges in the area that could support armored vehicles.

Engineers of Colonel Hermann Schulte-Heuthaus’s PGD Brandenburg were preparing the bridge for demolition when von Saucken arrived on the scene. He immediately ordered the demolition charges removed and instead put more men into the bridgehead, hoping that Nehring’s pocket could make contact.

Although the GD Panzer Corps was in serious danger of being surrounded, the Germans held their ground. Units of the 9th Army’s XL Panzer Corps were fighting on the GD’s northern flank, but the forward elements of Leliushenko’s 4th Tank Army had already crossed the Warthe in the south.

Inside the Nehring pocket the fighting raged on all fronts as it made its way toward Sieradz. Casualties mounted as men and equipment were blown apart by Soviet tank and artillery fire. Luckily for the Germans, the weather remained bad, preventing massive attacks from the Red Air Force.

As the 52nd Army moved into Rybalko’s former positions, its units attacked the German line with an artillery barrage before moving to engage the enemy. Colonel Mikhail Puteiko’s 254th Rifle Division pushed the 269th Infantry Division out of Kepno, which brought it about 65 kilometers from Breslau. The rest of Martriosian’s 73rd Rifle Corps followed. Along with the neighboring 78th Rifle Corps, the advancing infantry now set its sights on the city of Öls—only 25 kilometers east of Breslau.

Northwest of Krakow, Rybalko’s march to the south was already having its effect. German units were forced to retreat to avoid being cut off in the rear, and the 59th Army was able to move forward again.

North and east of Katowice, the Germans still held a defensive line. However, these defenders were also being threatened by Rybalko’s forces moving toward them from the northwest. With his forces spread so thin, Rybalko’s men were taking disturbing casualties as they met moderate to heavy resistance. One of those casualties was Maj. Gen. Nikolai Oganesian, the chief of artillery for Rybalko’s army.

The battle for Katowice continued without letup the following day. Forces from the 31st Tank Corps and Lt. Gen. Viktor Kirillovich Baranov’s 1st Guard Cavalry Corps were pushing toward Gleiwitz (Gliwice), about 20 kilometers west of Katowice. Following close behind were Gusev’s 117th and 118th Rifle Corps. The advance threatened the rear of von Edelsheim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, which was now under the control of the 17th Army, holding out north and west of the city.

North of Breslau the 4th Tank Army was assaulting Rawciz, about 22 kilometers east of the Oder. Directly east of Breslau, the hardpressed 408th Division and some Volkssturm battalions had to give up Namslau (Namyslow), located about 50 kilometers away. New defensive lines were nonexistent, and the only things slowing down the 4th Tank and 52nd Armies were the churned-up terrain and some hastily laid minefields.

By now, the Nehring pocket had broken up into several groups, each battling its way to freedom. On January 22, the battle group that Liebisch’s battalion was attached to made contact with elements of the Brandenburg Division after breaking through the Russian defenses. It gave only partial relief, since the survivors of the battle group found out that Soviet forces were already west of Sieradz, which meant more heavy fighting before they reached the Oder River line.

Although many units of the Nehring pocket were now making contact with von Saucken’s corps, more troops trying to escape were still spread out and cut off. About 65 kilometers east of Sieradz a trapped combat group containing part of the XLII Army Corps fought a desperate battle with second echelon troops of the 3rd Guards Army around the town of Petrikau (Piotrkow). The combat group was finally overcome, with some of the men taken prisoner. Most of the Germans were killed, including General Recknagel, commander of the corps.

Around Katowice, the Germans still held out north and east of the city. Stretched to the limit, Maj. Gen. Ernst Seiler’s 304th Infantry Division defended the area north of Gleiwitz against assaults from the 31st Guards Tank Corps. Seiler had just assumed command of the division after its previous commander, Brig. Gen. Ulrich Liss, had been wounded and taken prisoner the day before. On Seiler’s left flank Colonel Hans Kreppel’s 100th Jäger Division held off forces of the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps about six kilometers east of the Oder.

Konev’s forces reached the Oder on the 23rd, and Soviet engineers and assault units immediately set to work. The engineers of Pushkarov’s 6th Guards Mechanized Corps crossed the river followed by some motorized rifle forces and established a small bridgehead about 50 kilometers northwest of Breslau. In the 5th Guards Army sector, Rodmistev’s 32nd Guards Rifle Corps sent assault troops across the river around Ohlau (Olawa) and Brieg (Brzeg) between 25-35 kilometers southeast of the city. In many cases the Germans remained unaware of these crossings, allowing the Soviets to establish the jump-off points for future operations.

For the next two days the battle around Katowicz grew in intensity. The 1st Guards Cavalry Corps succeeded in wresting Gleiwitz from the 30th Infantry Division and the 20th Panzer Division, and the 118th Rifle Corps was advancing into the western suburbs of Katowice itself. Southeast of the city, Kurochkin’s 60th Army was pressing hard against Niehoff’s 371st and Arndt’s 359th Infantry Divisions, which were defending positions in front of the Polish town of Oswiecim, which was known to the Germans as Auschwitz.

The bridgeheads across the Oder were reinforced, and supplies began to be ferried across the river in anticipation of the assault on Breslau. Leliushenko’s 4th Tank Army was already pushing westward north of the city and was advancing on Steinau, which was only defended by a Volkssturm battalion and a couple of ad hoc combat groups.

To the north the floating pocket continued its westward flight. Bypassing Soviet concentrations around Ostrova, units of the pocket were able to destroy some Soviet supply columns as they fought their way to the Oder. By now Nehring’s pocket had moved ahead of von Saucken’s GD Panzer Corps, which was conducting a strong rearguard defense. Both groups hoped to reach the Oder near Glogau.

By the 26th, Konev’s armies had occupied the eastern bank of the Oder in an area 20 kilometers north of Steinau to Kossel (Kozle), about 90 kilometers south of Breslau. The only exception was a German bridgehead east and northeast of Breslau, which was occupied by the 269th Infantry Division and a mixed bag of combat groups that faced Martirosian’s 73rd Rifle Corps.

Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army had pushed German forces west of Katowice farther south, threatening at least three corps of the 17th Army with encirclement. Surprisingly, this presented Konev with a dilemma. His primary objective was to take the Silesian industrial area intact. A prolonged German defense of the area would be costly for the 1st Ukrainian Front and would more than likely destroy most of the industrial centers in the area, which was 110 kilometers long and 70 kilometers wide.

“I admit I was experiencing an inner conflict,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Several days earlier … I had issued orders for an encirclement.”

The opportunity to destroy approximately 100,000 enemy troops was very tempting. However, the close house-to-house fighting would cause frightening casualties. With the war’s end in sight, the losses would be a heavy burden for any commander. “As a result of my meditations I finally decided not to encircle the Nazis, but to leave a free corridor for their exit from the Silesian area and finish them off later, when they came out into the field,” he wrote.

To accomplish the plan, Konev ordered Rybalko to stop moving south and to make another 90-degree turn for an advance on Ratibor (Raciborz). He also ordered the 59th and 60th Armies to increase pressure on the Germans in the Katowice area.

On January 27, Colonel Fedor Krasavin’s 100th, Maj. Gen. Petr Zubov’s 322nd, Maj. Gen. Mikhail Grishin’s 286th, and Colonel Vasilii Petrenko’s 107th Rifle Divisions fought their way into Oswiecim. As the Germans retreated the Soviet troops came upon the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp complex. During the previous months the Germans had tried to destroy as much as possible within the camps and had evacuated most of the camp prisoners, but there were still about 9,000 left at the facilities.

The discovery did not generate much interest at the time. Majdanek concentration camp had been liberated on July 23, when the Russians took Lublin, so the existence of such camps was already known. Western newspapers had published photos of the camp, and they were too busy following events on the Western Front to find much time to report on the Auschwitz camp. The enormity of the crimes perpetrated at Auschwitz would only become known later.

Konev received reports about the camp, but he did not visit the scene. “It was not that I did not want to see that death camp with my own eyes,” he wrote. “I simply made up my mind not to see it. The combat operations were in full swing, and to command them was such a strain that I could find neither time nor justification for abandoning myself to my emotions. During the war I did not belong to myself.”

The final days of January proved Konev right in stopping Rybalko’s drive to the south. German forces in the Katowice area retreated through the corridor left open to them, and the 59th and 60th Armies captured the industrial area east of the Oder largely intact. Martirosian’s 73rd Rifle Corps had pushed the Germans out of their bridgehead east of Breslau, and the entire eastern bank of the river was now in the 1st Ukrainian Front’s sector.

In the north the forward elements of Nehring’s pocket finally reached safety near Glogau. During the final push to the Oder, General Block was killed on the 26th, making him the second corps commander in the 4th Panzer Army to become a casualty since the offensive began. As more units crossed the Oder, Nehring received orders to strike south along the western bank. Von Saucken was also ordered to strike south along the eastern bank of the river and hit the Soviets consolidating their positions in the area.

Lacking the panzers and personnel, it was an impossible order to fulfill. Although both generals complied, Russian strength was just too much to overcome. On February 2, the remnants of the GD Panzer Corps were able to cross the Oder on a pontoon bridge constructed by Nehring’s troops and join their comrades on the western bank.

That same day, the Soviets declared the Vistula-Oder operation completed. There were still pockets of German troops trapped on the eastern side of the Oder, but they were soon mopped up. Although still fighting the Germans south of the Silesian industrial area, Konev had achieved his primary goals. His troops had advanced up to 600 kilometers in 21 days, smashing the 4th Panzer Army and a good part of the 17th Army, and his forces were now moving to encircle Breslau. He had also saved much of the industrial infrastructure in eastern Silesia from destruction.

The Germans had lost tens of thousands killed and wounded. Entire divisions had been decimated and would never be rebuilt, while others were reduced to little more that reinforced battalions. Liebisch stated that his battalion of the 17th Panzer Division was reduced to about one third of its original strength. The battleworthiness of both the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions was rated low after the operation was finally over.

Konev’s losses were placed at 26,219 killed and 89,567 sick and wounded. His average daily losses were 5,034 soldiers. The 1st Ukrainian Front had lost about 10 percent of its total force, but many of those losses could be replaced.

With the conclusion of the Vistula-Oder operation, the Soviets were within striking distance of Berlin. Reinforcements, supplies, and equipment would have to be brought up for the Russian armies on the Oder before they were ready to strike out again. There were also German forces in Hungary, East Prussia, northern Poland, and on the Baltic coast that would have to be taken care of.

Although the war was not yet over, the end of the Third Reich was only a little more than three months away.

Author Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments