By John Wukovits

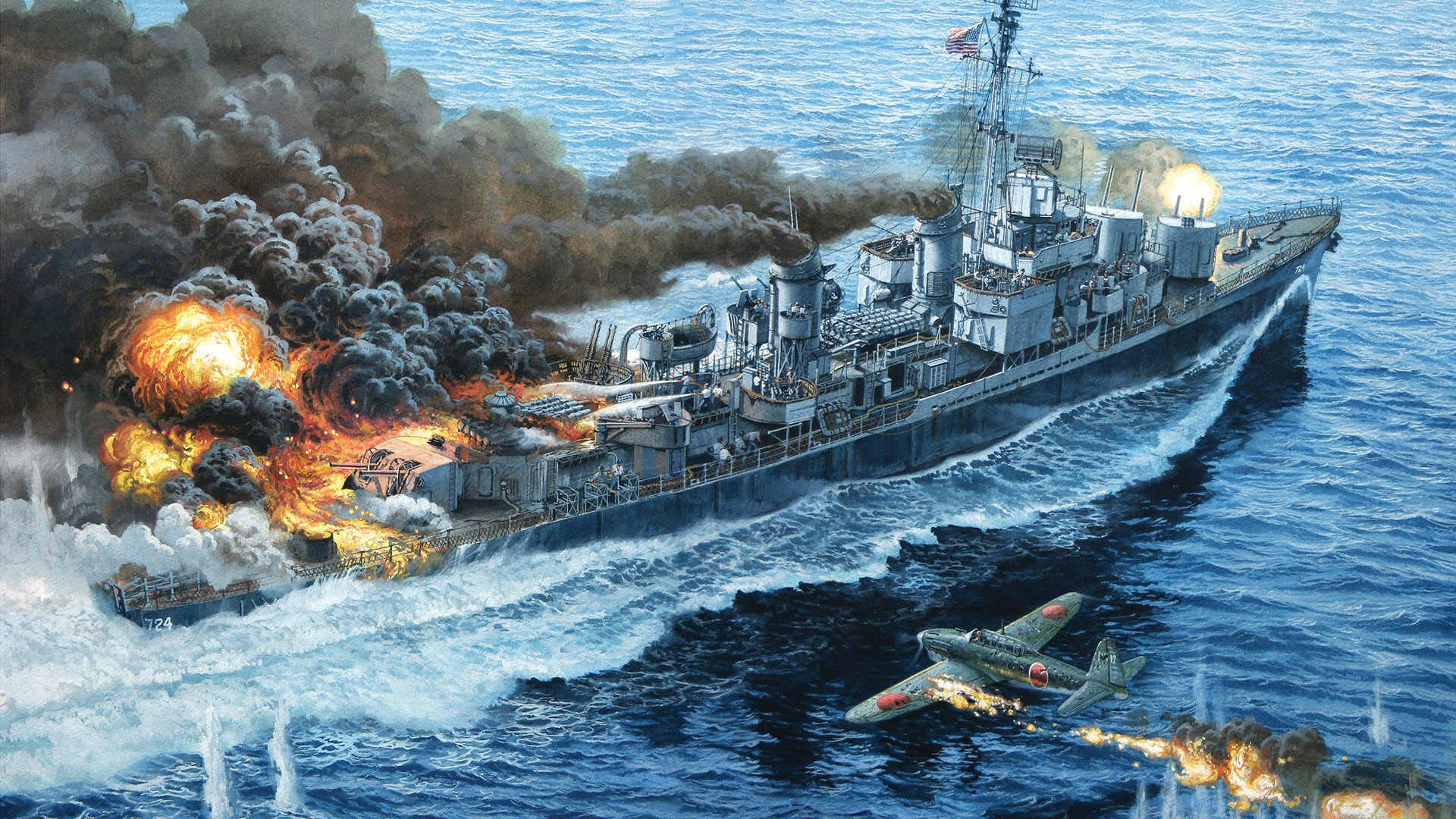

Two warships have been named in honor of Seaman Bartlett Laffey, a Civil War Medal of Honor recipient. The second Laffey was built as a Sumner-class destroyer by Bath Iron Works of Maine. Commissioned February 8, 1944, the USS Laffey (DD-724) had already amassed a proud record before her heroic stand on April 16, 1945. After participating in the June 1944 Normandy landings in France, where the crew battled German land batteries and provided gunfire support for the infantry ashore, the ship headed for duty in the Pacific.

[text_ad]

Unlike Normandy, where the German air arm was conspicuously absent, Laffey’s crew faced an intense air war off the Philippines––at Leyte and Lingayen Gulf, and also at Iwo Jima. For the first time in these battles, Laffey’s crew faced kamikaze aircraft and, although they then escaped unharmed, the officers and young sailors, led by the gifted skipper, Arkansas-born Commander F. Julian Becton, Annapolis Class of 1931, witnessed up close the horrific damage just one suicidal pilot––never mind a whole swarm of them––could do by purposely smashing into a ship.

“All Hell Broke Loose”

The crew’s main ordeal occurred on April 16, 1945, off Okinawa, an island only 350 miles south of the Japanese home islands. While Laffey prowled the waters at Picket Station No. 1, the northernmost and thus the most dangerous of the 16 picket stations ringing Okinawa, the destroyer’s radar screen suddenly filled with blips. In the next 80 minutes, 22 kamikaze aircraft broke off from their companions to attack the ship. Laffey’s gunners, superbly trained by Becton, splashed the first eight, but as the following account depicts, the next four ravaged the ship’s aft section.

The battle’s opening quarter hour had gone well for Laffey. Commander F. Julian Becton’s skillful maneuvering and the gunners’ accuracy had dispatched the first eight kamikazes, but the agony of the afterdeck, 25 minutes of unadulterated hell, left survivors stunned with the ferocity of the attack.

In three harrowing minutes four separate enemy aircraft converged on the destroyer from four angles—two from port and two from starboard. Like a boxer absorbing a series of blows, Laffey took four punches in a remarkably brief, and deadly, stretch. “They came in thick and fast after that, beginning with the ninth plane,” said Commander Becton of the kamikazes that attacked his Laffey after the first eight had been shot down.

Fire Controlman 3/c George R. Burnett tried to describe for his parents what next occurred, and wrote that “all hell broke loose.” He added, “They all started to dive on us at once and poor little us all by ourselves out there so you can see we didn’t have much of a chance because they were coming from all directions and you just can’t shoot every way at once.”

At the bridge, teenaged Quartermaster 2/c Aristides S. “Ari” Phoutrides noticed that after the first eight kamikazes, “They came in groups of ones and twos. It almost appeared that they waited their turn. At one time we had seven Vals [Aichi D3A] circling overhead that didn’t attack us until a few others went in. They used all the tricks they could—flying low, coming in fast, and diving from the sun. In fact, many of them made bombing runs on us before attempting a suicide dive. All of them,” he added somberly, “strafed as they came in.”

In the CIC below the bridge Lieutenant Lloyd Hull, a product of the University of Pennsylvania’s Naval ROTC, supervised the men who operated the ship’s communications system, including the recently added FIDO team. Leaving control of events outside the CIC to Becton and the men on the guns, he focused on his main responsibility—to collect and relay to Becton the information he needed, such as targets spotted and the numbers of friendly aircraft in the area, if any, to arrive at the decisions he had to make with lightning speed.

As the battle swirled above, radarmen plotted surface and air targets, while radiomen and others manned the communications apparatus that linked the ship to the flagship, to other vessels, and to the outside world. Crew called “talkers” reported to Hull any updates they received over their circuits from the overtaxed lookouts on deck, and relayed information given them by Hull to Becton and other recipients.

Like Sonarman Daniel Zack in Mount 52, Hull and the others in CIC labored in a closed world, blocked from witnessing the battle raging outside. Unlike Zack, Hull and his crew could at least follow the progress from the radar screens and any communications that arrived. Hull wished he could have observed more, and knew that a kamikaze could at any moment ravage his CIC and end his run as an officer, but he concentrated on his tasks and tried to be as helpful as he could to Becton and, ultimately, to his shipmates. Maintaining a flow of information to the bridge was the prime manner in which he could best contribute to the action, for without it, Becton would be blindly skippering his ship.

As he moved from radarmen to talkers, Hull wondered how his friends on deck fared. He knew he was fortunate to work in CIC, where the bulkheads protected him and his men from the bullets and shrapnel that would undoubtedly sweep the decks with each crash, but in some ways he longed to be above, sharing the hazards with those he had commanded and those with whom he had grown close.

Long-range radar, able to discern targets up to 60 miles away, has difficulty locating low-flying planes. With his CAP still missing and his SG surface-monitoring radar already disabled, Becton leaned on the young eyes of the ship’s lookouts, most of them recent high school graduates. Until CAP arrived and imposed themselves between the kamikazes and Laffey, Becton would have to rely on his own resources.

A Fiery Impact

At 8:45 am, one of his sharp-eyed lookouts spotted a Judy [Yokosuka D4Y] coming in low on the port side. As he drew closer, the pilot banked slightly and then aimed at the ship’s mid-section, hoping to destroy the bridge area. Even though the Judy, armed with a 1,750-pound bomb, raced in at more than 300 miles per hour, men on the port side guns were surprised that the aircraft created the illusion of moving toward them in slow motion.

Lieutenant Joel C. Youngquist checked the men on his 40mm and 20mm gun crews, one level above Gunner’s Mate 2/c Lawrence H. “Ski” Delewski’s five-inch gun on the main deck, but Seaman Tom Fern and the other men had opened fire almost as soon as the kamikaze was spotted. Fern and his companions stood their ground, exposed to the bullets pinging around them, and battled the instinct to crouch below the waist-high shield as the plane bore in.

While Becton executed frequent course changes to keep the plane away from the ship’s vital mid-section, Lieutenant Frank Manson watched the kamikaze, uncertain whether it would veer toward the bridge and him or plunge directly into Youngquist’s gun. Survival at this moment relied on those portside 40mm and 20mm guns, the ship’s last line of defense, to knock down the plane. “You know he’s [the kamikaze pilot] going to die—you pray he won’t take you with him,” Manson said. “You’re up against a desperation and fanaticism that leaves you cold all over.” Manson had witnessed other suicide attacks in the Philippines, but this was “blood-chilling. They [kamikazes] have a kind of insanity that makes war more horrible than it’s ever been before.”

Seaman Fern handed four-shell clips to his gunners, who fired them as rapidly as the loader placed them in the guns. Spent casings clanged into bins on the deck, adding their noise to the pow-pow of the 40mm guns and the rapid tat-tat-tat-tat of the 20mm guns. In return, bullets from the aircraft pinged off shields and mounts, igniting sparks and cutting into human flesh and bones.

Bullets from Laffey gunners kicked up hundreds of splashes in the water as they attempted to down the low-flying plane, making it appear as if crew could traverse from ship to plane by hopping along the splashes. Tracers nicked the aircraft, and the plane shuddered as 20mm slugs pierced the fuselage and wings, but on it came, astounding gun crews who had the target directly in their sights. If they could not hit the plane in the next few seconds, Fern and everyone else would become part of a fiery eruption that would turn the aft section into their funeral pyre.

Despite the 430 rounds fired in half a minute by the 40mm and 20mm guns, the kamikaze pilot barreled through. Men near Fern instinctively put their arms up to shield their faces as the moment of impact approached. The plane passed just behind the motor whale boat resting in its cradle and rose slightly above Mount 44, barely missing Fern and the gun crew at that station.

As its landing gear and part of one wing struck the two 20mm guns of Group 23 near Fern, burning gasoline spurted from the mangled wing and ignited a raging fire. The remainder of the plane tumbled over the starboard side and exploded close to the ship.

Men tried to process what they had just witnessed. “The shock, the flash of flame, the split second of awful silence, suddenly torn by the cries of injured men and the impassive voice of a bos’n on the bull horn, ‘Fire, after deck house,’” wrote Lieutenant Manson after the battle. “The realization that it had actually happened. The pain of realization that Laffey, with all her power and security, like all other ships, was vulnerable to death and destruction.”

A resounding jolt from the plane’s impact and the explosive force of the bomb attached to its fuselage shook everyone in and near Lieutenant Youngquist’s guns and resonated throughout the ship. Seaman 1/c Robert Powell, who was tossing depth charges over the starboard side to prevent fires from igniting them, thought that a freight train had just smacked head-on into Laffey.

The force of the blast hurled Seaman 1/c William L. “Lake” Donald out of a 20mm gun mount and under a torpedo tube. Shaken but unharmed, the sailor regrouped and rejoined his crew. Intense heat and flames enveloped the deck and mounts, trapping men in a lethal inferno. Shrapnel ripped through metal fixtures and human flesh, decapitating one man, wounding or temporarily blinding many others, and severing power cables connecting nearby stations to the bridge.

Battling the Fires Aboard the USS Laffey

As happened with each kamikaze that rammed into Laffey, the impact spread gasoline over the adjoining area. The flammable material flooded Youngquist’s gun mounts on the superstructure deck, eight feet above the main deck, and quickly ignited, engulfing men and equipment in a conflagration. Youngquist’s Mount 44 and his 20mm guns were knocked out of commission, and Seaman 1/c Ramon Pressburger’s Mount 43 directly across on the starboard side was badly damaged by the flames. The flames cooked off ammunition resting near the 40mm and 20mm guns, creating a fireworks display that punctured hundreds of holes in the superstructure deck.

Gasoline and flames quickly poured through those holes into the handling room below Mount 44, threatening to ignite the store of explosives earmarked for Youngquist’s gunners. The conflagration spread into men’s quarters and a washroom belowdeck, burned or severed electrical cables, and created noxious gases that raced through the venting system into the engine room.

Youngquist administered first aid to a man severely wounded by shrapnel from the explosion, then gathered four men to counter an immediate threat—the collection of four-shell clips of 40mm ammunition standing near the guns. Should most of the unused ammunition detonate, the result would be the maiming or deaths of most men around Youngquist’s position, seriously reducing the chances that the ship and crew would survive.

Youngquist, Fern, Seaman 1/c Charles W. Hutchins, Machinist’s Mate 3/c Donald J. Hintzman, and others ran to the shells and began tossing the clips over the side. Disregarding their personal safety, they hurled the ammunition into the ocean, despite pain from blistered and badly burned hands. “We used bare hands at first,” said Lieutenant Youngquist. “We then wrapped cloth around the hands. What we did came from natural instinct. We were not trained for this.”

The men worked as fast as they could to reduce the stockpile, but there were too many gun emplacements and too many shells for them to dispose of them all. With raging fires drawing closer, ammunition started to explode. Razor-sharp shrapnel sliced through men and materials and punctured additional holes in the deck, through which more gasoline and flames gushed down to areas below.

Ignoring the aerial attacks from additional kamikazes, Youngquist organized efforts to contain the fires that ravaged the aft part of the ship and prevent additional damage to the destroyer. Men grabbed hoses from the main deck amidships and raced to Youngquist’s superstructure, where the officer directed them in spraying cooling waters onto burning plane wreckage, unspent 40mm shells, and the fires that had spread from his deck to areas below his gun position.

Tom Fern administered first aid to a wounded man before ignoring the exploding shells and raging fires to direct streams of water onto the worst part of the conflagration. “I was just trying to keep busy,” he said. “I was trying to keep my mind from what was happening.” Fern did not fear the bombs on the enemy aircraft as much as he did the gasoline the planes carried, which upon impact with the Laffey created “an enormous fireball. If that fireball caught you within 60 feet, you were dead.” There was no sense seeking shelter anyway, for where on the small ship could he find refuge?

Meanwhile, the force of one explosion blew Ship’s Serviceman 2/c Jim D. Matthews into the ocean as he battled the fires. The cooling waters quickly extinguished the flames that covered part of his body, but he barely avoided being chopped up by the ship’s propellers as Becton executed another turn. Matthews drifted in the water, fearing he might be hit by falling bits of aircraft, shrapnel, or strafing, and became a spectator to the battle around him.

When Metalsmith 3/c Rex A. Vest was also blown overboard, Matthews swam over and helped Vest with his jacket. The pair remained in the waters until a rescue craft picked them up after the battle.

After hitting Youngquist’s mounts, the kamikaze had cartwheeled over the top of Mount 43, the starboard 40mm gun directly across from Youngquist, spewing gasoline over the mount and setting men afire. Most of the gun crew scrambled over the mount’s side and tumbled to the deck below, but Gunner’s Mate Robert Karr, the gun captain, and Seaman 1/c K.D. Jones Jr., his pointer, had trouble getting out.

As exploding ammunition screamed by, the pair crawled on their stomachs around the gun tub toward the aft stack, hugging the deck to keep out of the way of the flames and ammunition. Karr and Pointer reached the gunner shack beneath Mount 41, the forward 40mm gun closer to the bridge, where Karr paused to regroup and to say a prayer. Gaining solace and strength from the moment, Karr continued to the main deck, where he helped treat wounded men.

“Everywhere You Looked You Saw Dive-Bombers or Fighters Converging on You”

The heroic efforts of Youngquist, Fern, and their mates had, for the time being, contained the fires and prevented Laffey from exploding into an uncontrolled inferno. However, Becton could not ignore the obvious—that more kamikazes would soon be rushing at the mauled ship to administer the coup de grâce.

“They like to find cripples,” he said after the battle. “They’ll go after one that’s smoking.” He could not hide the flames or the black smoke that curled upward from the damaged destroyer and made Laffey an attractive target, “for the smoke towering above us marked us a crippled ship.” Becton glanced skyward and said later that “everywhere you looked you saw dive-bombers or fighters converging on you. All you could do was hope your gunners would get them.”

Becton remembered his vow when he had faced dire situations in the Solomons and watched Japanese aircraft knock out two ships. The Japanese might be licking their chops over attacking a hamstrung vessel, but “they found out we were far from knocked out” and would soon learn that “we’d give them a fight.”

While Lieutenant Youngquist and his men battled the fires from Kamikaze No. 9, which had engulfed much of his gun position, the next two attackers converged to Youngquist’s rear, targeting the fantail gun crews and Delewski’s five-inch mount.

Kamikaze No. 10, a Val dive bomber, drew within one half mile of the ship before being spotted. The pilot flew so low to the surface that some of the crew thought the waves might slap the plane down, and arrived so suddenly that Delewski’s men had no time to turn and fire the mount.

That left the defense to the three 20mm gun crews on the fantail, who fired only a few rounds before the plane was on them. They remained at their posts in the gun mount and fired gamely as the kamikaze zoomed toward them, with the pilot answering their machine gun bullets with those of his own. Japanese slugs clanged against mount shields and deck, while American 20mm shells tore off pieces of the Val, but the suicide-bent pilot barged through the hail of bullets and the smoke from the preceding kamikaze to smack directly into Radioman Lawrence Kelley and the others.

“You know, some of those kids have more damned guts,” said the ship’s executive officer, Lieutenant McCune, of the ship’s gunners. “They stayed right in that gun mount and kept firing.” Like everyone else aboard Laffey, McCune hoped Laffey could avoid further harm, “But it doesn’t make any difference how good they are. You just can’t get them all.”

Kamikaze No. 10’s landing gear ground into the fantail just inboard of the starboard depth charge rack, gouging an indentation in the deck two feet deep and three feet wide. The plane smashed against the aft and forward gun shields around Kelley and his shipmates, sending parts of men and machine flying through the air and knocking out of commission the three 20mm guns of Group 25. The kamikaze then crashed into the starboard aft corner of “Ole Betsy,” Delewski’s Mount 53, where the plane and its bomb exploded, disintegrating the pilot and whipping plane parts forward and aft.

The collision created pits in Delewski’s gun barrels up to 11/2 inches deep, blew the gun mount shield upward several feet, punctured large holes in the mount and the surrounding deck, and started new fires that soon joined those already endangering Youngquist’s men. Additional gasoline and flames gushed through the deck holes into the crew’s quarters below, sparking widespread fires that destroyed personal items and severed hydraulic and electrical lines.

Kamikaze No. 11

Kamikaze No. 11, another Val that had drawn within one-half mile of the ship’s starboard side before being detected, dropped a bomb that exploded two feet inboard on the starboard side, piercing the deck plating and creating a hole six feet square in the starboard edge. The pilot and plane then disintegrated as they smashed into the metal mounts, pulverizing bodies and bursting into flames against the starboard side of Delewski’s Mount 53, causing further devastation to a gun already badly damaged by the preceding kamikaze. Additional flames turned Laffey’s aft section into a firestorm, and black smoke billowed to the heavens, where more kamikaze pilots waited their turn.

Delewski had just selected the next target for his gun and shouted to Coxswain James M. “Frenchy” La Pointe to turn the gun 135 degrees when the kamikaze hit. The explosion tossed Delewski, who had been standing in the open door on the side of the mount, 15 feet upward and away from the mount. Had La Pointe turned the gun one or two more degrees, Delewski would have been blown out in the direction of the flames; had La Pointe turned the gun a few degrees less, Delewski would have been propelled over the side into the ocean. Instead, he landed on the port K-gun depth-charge thrower.

When he regained consciousness, still draped over the K-gun, the stunned gun captain was surprised to see that he had suffered only minor burns and scratches. Groggy from the explosion, he slowly rose as men tossed unexploded shells over the side, and stumbled back to the mount. As he neared his damaged gun, Delewski heard a familiar voice moaning, “Ski, please help me.” The engine of the plane that smashed into the mount had pinned his closest friend, Coxswain Chester C. Flint, to a bulkhead. Delewski tried to free the stricken Flint, but his buddy died before Delewski could extricate him.

Delewski had no time to mourn as, 10 yards away, flames engulfed another of his crew, Seaman 1/c Herbert B. Remsen. He rolled Remsen around to extinguish his burning clothes, saving the sailor’s life. Even though the seaman suffered burns to his face, left arm, and hair, he returned to the action.

The same explosion threw Seaman 2/c Merle R. Johnson out of the mount and set him afire. “I woke up on the portside hatch to the head,” said Johnson. “Someone was spraying me with salt water because I was on fire.” Crew manning hoses directed streams of water on Johnson to douse the flames, then carried him to the wardroom, where Darnell and his assistants carefully removed Johnson’s jacket because the apparel’s zipper had melded with his skin. “Burnt all over,” said Johnson, “I lay in front of a blower from the engine room. The warm air felt soothing on my burns.” The battle was over for Johnson.

Burned and nicked by shrapnel, Boatswain’s Mate Calvin Wesley Cloer, the preacher with two religious names, shuffled to the wardroom for treatment. He took one look at the busy Darnell, inundated with disfigured wounded and dying men, and turned back to the mount. His shipmates needed treatment more than he did. He could handle a little pain, he concluded.

Across the deck, Fern battled the fires from Kamikaze No. 9 when he heard a man shout, “Plane coming in!” As men scattered to get out of the way of the aircraft and abandoned fire hoses shot water in all directions, Fern turned to see Kamikaze No. 11 just yards from the ship. Fern leaped over the side of the mount to the deck just as the plane impacted against Gun 53, emitting heat that immolated some crew and badly burned Fern. “Shoes, belts, flak jackets and helmets,” Fern said later. “Everything else was completely burned away.” Lieutenant Jerome Sheets perished in the explosion.

Although partially blinded from smoke and flash burns to his face, Fern returned to the gun mount, retrieved his hose, and sprayed water onto burning areas until, weakened from his injuries, he had to be helped away to receive treatment from Doctor Darnell. Fern had been so focused on his task that, combined with the effects of his injuries, he lost all recollection of events until after the battle. Later, as Fern was being treated for brain concussion on a hospital ship, his shipmates told him what he had done.

In the meantime a new peril arose. Baker 1/c William H. Welch reached the bridge to report that flames threatened to ignite the five-inch shells stored in the ship’s handling rooms below Mount 53. When Becton gave him permission to flood the rooms with salt water, Welch raced back just in time to open the valves and let cooling seawater into three ammunition rooms before the potent shells ripped Laffey in half.

The three kamikazes inflicted heavy blows to aft section personnel and equipment. Most of the crew manning the fantail 20mm guns were killed, including Gunner’s Mate 1/c Frank W. Lehtonen Jr., who had earlier refused treatment for a shrapnel wound and now perished at his post, and Radioman Lawrence Kelley, whose soothing Irish tenor voice had often entertained the crew.

Delewski’s mount had suffered extensive damage. Six men had perished in the mount’s blazing interior, including Frenchy La Pointe and Chester Flint, and six more suffered burns and internal injuries. Fires and explosions put Youngquist’s guns out of action. “The whole stern of the ship was under a coil of smoke,” said Becton after Kamikaze No. 11 ploughed into Laffey.

A Devastating Bombing Run

Only one minute after the previous pair, Kamikaze No. 12 attacked. While Laffey’s guns focused starboard, at 8:48 another Val came out of the sun in a steep glide, approached from the stern, leveled off near the water’s surface, and turned toward the ship. From his post at the starboard side K-guns, Torpedoman’s Mate Fred Gemmell watched yet one more plane attack in what appeared to be a long line of kamikazes waiting to take their turn at his ship.

“Guns firing and planes coming in,” said Gemmell. “When you heard gunfire, you paid attention to where it came from and what was happening. I recall thinking I wanted to get the heck out of here, but there was no place to go.”

The ship’s 20mm guns near the aft stack fired 120 rounds at the plane, but the pilot avoided the gunfire and dropped a bomb that landed on the port quarter above the propeller, punctured through the deck, and exploded in a 20mm ammunition room. The pilot, who had apparently decided to drop his bomb without smashing into the ship, evaded intense gunfire as he flew to starboard and disappeared beyond the horizon.

The solitary bomb caused astounding damage. The bomb punctured a seven-foot hole in the deck, three feet inboard from the ship’s edge, twisting the main deck upward in the process. It ignited new fires and added fuel to those already ablaze, where damage control personnel battled “raging fires dangerously near the after magazine.” Every gun aft of the ship’s No. 2 stack had now been knocked out of action.

The bomb burst through the opening in the main deck to explode in the 20mm magazine, where fires speedily engulfed crews’ quarters and storage areas. The force of the explosion thrust pieces of bunks and bulkheads from the ship’s interiors upward and out through hatches, raining deadly shrapnel onto the deck crew.

Shrapnel belowdecks ruptured or pierced the bulkheads of seven adjoining compartments, including the steering gear motor room, the carpenter’s room, and the steering gear room. The bomb’s explosion ripped bulkheads from hinges, threatened the ammunition storage areas, and produced thick smoke that hampered damage control operations. Bomb fragments penetrated both the ship’s deck and skin, allowing water to gush through and flood the aft end.

More alarming, in Becton’s view, was that the bomb damaged the ship’s steering ability and hampered his ability to maneuver. Flying fragments ruptured hydraulic leads in the steering gear room located beneath the fantail and jammed the ship’s rudder while it was turned 26 degrees to port. With the rudder locked in position, the ship steamed in a perpetual circle, leaving Becton with only one evasion tactic at his disposal—confuse the enemy by rapidly increasing or decreasing his speed. “Evasive maneuvers were confined to rapid acceleration and deceleration, as the ship swung through tight circles with full engine power still available,” explained Becton.

“Now Laffey Circled Madly Like a Wounded Fish”

Becton faced a grim situation. Four kamikazes had smashed into Laffey’s aft quarter on three sides. He had lost the ability to maneuver, guns no longer protected the ship’s stern section, and flooding in the aft areas hindered his attempts to change speed. The rear one-third of Laffey was a smoking clutter of mangled steel and dying crew. Unless Becton’s damage control parties contained the fires and flooding, it would only be a matter of time before the end approached.

“Now Laffey circled madly like a wounded fish,” wrote Lieutenant Manson after the fight had ended, “black smoke coiling above her like trailing viscera.” Becton agreed. “We weren’t quite a sitting duck,” said Becton, “but we felt like one.”

Unable to control the steering from the bridge, Becton tried to contact Seaman Andrew Martinis in the aft steering room directly below the fantail to determine if Martinis could steer from that post. Because the telephone lines connecting them had been severed in the attack, Becton was forced to send two men aft to check on the situation.

At the same time Lieutenant Theodore Runk, who had been organizing the fire-fighting efforts aft, left to see if he could free the jammed rudder. He worked his way through debris and bodies, stopping to toss overboard an unexploded bomb. When he arrived, he and Martinis disappeared into the aft steering room, already filled with smoke from the burning 20mm ammunition-handling room adjoining it.

“It was hard for us to breathe,” said Martinis. “Runk had a wet handkerchief and he would cover his face, breathe, and then hand it to me.” Passing the wet handkerchief back and forth to shield their faces from the smoke and flames, Runk and Martinis found that the hydraulic lines leading into the emergency steering room had been cut during the attack.

Martinis moved into the steering gear room behind the steering room to see if he could free the jammed rudders, but could not budge them. “The smoke was getting thicker for us,” said Martinis. Unable to relieve the pressure on the rudder and give Becton full maneuverability, the pair exited before their air supply ran out.

“Well, that jammed our rudder all the way over to port,” George Burnett wrote his parents after the battle. “So we were doing 30 knots around in circles and we had no guns aft to shoot with.” Becton faced a terrifying quandary. He required top speed to avoid the kamikazes that were certain to approach, but top speed would further fan the flames that already threatened the destroyer. If he slowed the vessel to give his damage control teams time to combat the fires, he presented a more enticing target to the kamikazes.

A handcuffed Becton slowed the ship during the infrequent lulls, and then called for maximum speed whenever lookouts announced the arrival of another attacker.

The Quartermaster’s Inspection

Needing a clear picture of the damage aft, Becton asked Quartermaster Ari Phoutrides to leave the bridge for a quick inspection of the area. Phoutrides exited the bridge to the port side main deck below and slowly wound aft through the plane wreckage, death, and debris that littered his path. Although suffering serious wounds to his back and head, Seaman 1/c Marvin G. Robertson carried bloody Seaman 2/c Walter Rorie to the wardroom for treatment. Phoutrides passed by the body of a shipmate who had been burned to a crisp. The man’s arms and hands covered his face, and he was frozen in a charcoal rigidness that depicted his final act of unsuccessfully warding off the blazing gasoline. Without pausing, Phoutrides gingerly moved aft alongside Delewski’s Mount 53, now more a smoking, dented hunk of metal than an instrument of war, and approached the fantail.

“Then I saw the damage to the 20mm guns on the fantail,” said Phoutrides. “There was a man still in his straps with both legs gone, bleeding. He was still alive and was begging, ‘Please get me out of these straps.’” Phoutrides sickened at seeing the man’s legs lying on the deck not far from the mortally wounded sailor, but regrouped to aid others who rushed to the man’s side. Before they could lift him from the straps, the man succumbed.

Only feet away, a cluster of bodies from the fantail, including Radioman Kelley, lay grotesquely among the debris, mute testimony to the carnage inflicted by the kamikazes. “I saw five of them, all in different positions, one was flat on his face,” said Phoutrides. He made mental notes of everything he observed—the burned guns and mounts, the decks punctured with hundreds of holes, the fires and smoke, the cries of the wounded, and the silence of the dead.

“They were all just lying there. It didn’t hit me much, right then. I didn’t get much reaction,” Phoutrides said. “Then I went back toward the bridge, and got to thinking about it. Suddenly I knew I didn’t want to see it again.”

Phoutrides thought he had witnessed the worst until, on his way back to the bridge along the starboard side, he “came upon three men just forward of Gun 53. The group had been hit, and it was more gruesome than the 20mm fantail guns. The three had been on damage control and were together, at a post, waiting for orders or something. A plane smacked right into them. There was nothing but bits and pieces of them left.”

Phoutrides nudged the gruesome sight out of his mind and continued to the bridge. Along the way he came across his friend, Torpedoman’s Mate John Schneider. “As I passed him I asked, ‘How’s it going?’ He said, ‘Greek [Phoutrides’s nickname], if I could find a piece of rust on this ship I’d crawl under it!’” Phoutrides and Schneider shared a mild laugh at the remark before the quartermaster completed his inspection and reported to Becton.

He delivered a sobering summary. Both the main deck and the superstructure deck aft, upon which rested many of the ship’s guns, were a mass of flames. Enemy planes, bombs, and shrapnel punctured holes in the decks ranging from inches to several feet in diameter. The fantail was “all the way down in the water and still going down farther,” engines and aircraft pieces protruded from gun mounts and belowdecks compartments, and every gun aft had been destroyed or badly damaged. Smoke billowed skyward, while flames on deck and flooding belowdecks threatened to scuttle Laffey before additional kamikazes even had the chance.

Yet hope remained. “Sure, our radar was gone and the rudder was jammed and almost every compartment aft of the stacks and engine rooms was flooded,” said Delewski, “but Laffey still made steam and continued moving in a circle. But we were moving.”

Recovering the Laffey

Despite the damage inflicted by the four kamikazes in less than five minutes, Laffey’s crew continued to battle 10 additional aircraft before their nightmare finally ended. Gunners splashed more enemy planes before they smashed into the damaged destroyer, but others raced through heavy gunfire to further harm the vessel.

Most of the crew could hardly believe their ship remained afloat after the last kamikaze had ended its run. Flames ravaged gun mounts and raged belowdecks, smoke billowed to the sky, and injured and dying men lay on charred, blood-soaked decks.

During the 80-minute engagement that seemed like an eternity for the survivors, five kamikazes and three bombs struck Laffey, and two bombs scored near misses. Thirty-two of her 336-man crew were killed and more than 70 were wounded.

Tugs safely brought the destroyer to port, where temporary repairs enabled Commander Becton to inch across the Pacific to Seattle and a warm reception from the press and public. In an effort to remind civilians that the war was not yet over, the Navy Department made the ship—damaged gun mounts, punctured decks, and all—available for public viewing.

Laffey was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and earned five battle stars for her service during World War II. After being repaired, she was present (as a support ship) for the atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1946 (Operation Crossroads). On June 30, 1947, Laffey was decommissioned and placed in the reserve fleet. Recommissioned in 1951, Laffey earned two battle stars during the Korean War and in 1962 underwent FRAM II (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization) conversion and served in the Atlantic Fleet until decommissioned in 1975.

The gallant Laffey, the only surviving Sumner-class destroyer in North America, remains afloat today, berthed since 1981 at Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, along with the carrier USS Yorktown (CV-10), commissioned in 1943. The public can still walk Laffey’s decks and relive that heroic April day 70 years ago. She was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Becton, who retired from the Navy in 1966 with the rank of rear admiral, wrote about the Laffey’s experiences in his 1980 book, The Ship That Would Not Die.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments