by John W. Osborn, Jr.

Spanish Legionaries charged into battle crying, “Long Live Death.” They sang of being “the Bridegrooms of Death” and proved they meant it with over 10,000 killed and 35,000 wounded. The Legion’s credo was “blind and ferocious aggressiveness in the face of the enemy.” The enemy would eventually be the Spanish people.

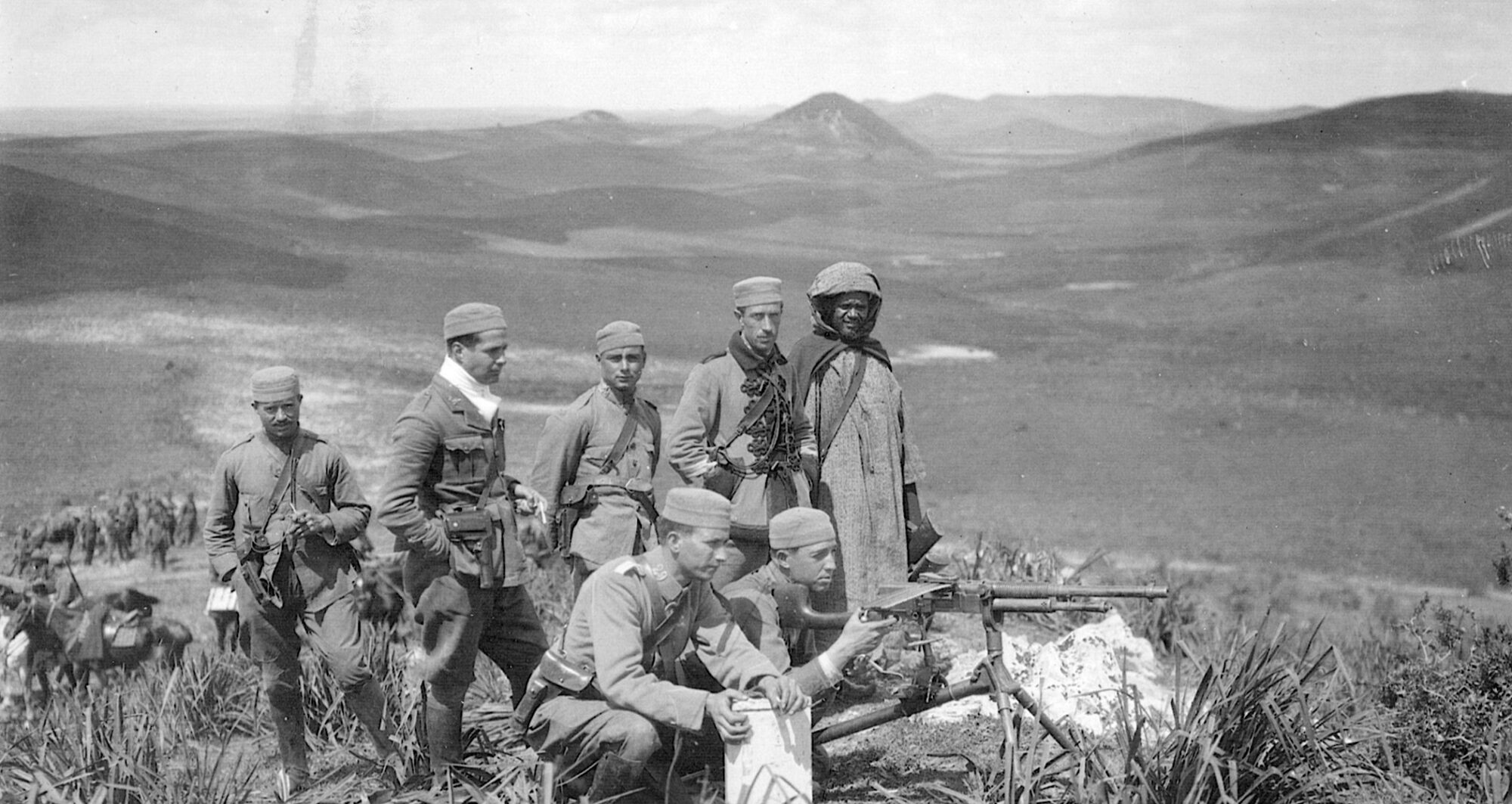

North Africa created the impetus for Spain—as it had for France in 1830—to establish a foreign legion. In 1904, Spain split Morocco with France, taking a protectorate in the north and with it the ferocious Berber tribes of the Riff Mountains. In 1919, those tribes rose in revolt under Abd-el Krim and began slaughtering barely trained, incompetently led conscripts in the thousands. The scenes might have been from paintings by Goya.

To counter this mayhem, Major Jose Millan Astray, a veteran of colonial war back when Spain still owned the Philippines, lobbied for the type of professional, international vanguard that France possessed. Thus, on August 31, 1920, by royal decree King Alfonso XIII created one.

“A Motley Band of Desperados, Misfits and Outcasts”

Officially the Regiment of Foreigners (Tercio de Extranjeros), it was commonly—and preferably by its leaders and men—known as the Foreign Legion (Legion Extranjeros). No matter what the name implied, however, Spain’s “foreign” force would be 90 percent Spanish 90 percent of the time. The first commander, inevitably, was Millan Astray. For his deputy he made a fateful choice, starting an obscure ambitious officer on the road to eventual command of the Legion and of Spain itself: Captain Francisco Franco.

The Legion that fought in Morocco was described by Franco’s main English language biographer, Paul Preston, as “a motley band of desperados, misfits, and outcasts, some tough and ruthless, others simply pathetic.” They were primarily disgruntled, disoriented World War I veterans from both sides, hired killers from Barcelona, fugitives from the law, adventurers, and the hungry off the streets. Among the Beau Geste types were a Russian prince, a Polish count, a circus clown, and a former friar seeking penance. In the mixed bag could be found Italian, German, Austrian, South American, Portuguese, Maltese, French, Swiss, and British (who actually expected tea breaks!). There was Prussian Carl Tieden Zaden, who became the Legion’s most outstanding and decorated non-Spanish officer (He would be posthumously appointed the Legion commander after dying of wounds in the Civil War to come). There was the first of only two Americans known to have served in the Legion, a black man named William Brown.

Millan Astray

There could have been no more strangely apt figure to preside over and mold—or sledgehammer—such a military mob into an effective fighting force than Millan Astray. A regular sergeant, Arturo Barea, vividly described watching Millan Astray while his “whole body underwent an hysterical transfiguration” as he shrieked at recruits about how they had come to die, then brutally beat a mulatto who talked back to him. He had been and would be wounded so many times (eventually losing an arm and eye) that he became known as “The Glorious Mutilated One.” In the words of the Spanish Civil War’s preeminent historian Hugh Thomas, Millan Astray was “a man from whom there seemed more shot away than there was of flesh remaining.”

Obsessed to the point of being mentally unbalanced about living down the public disgrace of his policeman father going to jail for bribery, Millan Astray fervently believed that “Death in combat is the highest honor.” Instead of the white kepi French Legionnaires venerated, he created a mystique surrounding death with his choices of anthem and battle cry. To what extent they reflected an understanding of the fatalist, outcast mentality of the legionary or mere near madness, his methods ultimately work–at a cost of brutality.

Pay Was Better; Treatment Proportionately Worse

For if Legion pay was better than the regular army (60 cents a day compared to 20 cents), the treatment was proportionately worse. Eighteen recruits perished on a nonstop 36-hour forced march. Discipline was enforced by the firing squad, often without trial, not just for desertion but even trivial offenses. The most notorious case of this was for throwing a plate of food at an officer. (Even today, Legion discipline remains based on fear, with bungling recruits belted and disciplinary problems beaten.) Legionnaires would pass on this treatment to civilians and prisoners.

“The black and yellow flag of the Tercio was to be prominent in all the ensuing campaigns in Morocco,” David Woolman wrote in Rebels in the Riff. Franco routinely exposed himself to enemy fire and was never hit, even when Millan Astray, standing next to him, fell with a bullet in the chest. On June 5, 1923, Lieutenant Frederico de la Cruz was awarded the first of 22 Laureate Cross of St. Ferdinand medals presented to Legionnaires. This was Spain’s version of the Medal of Honor or Victoria Cross. (Reflecting either predominance or prejudice, they would all go to Spaniards.)

Atrocities Committed Against Moorish Villages

Legionnaires spearheaded offenses, climbed mountainsides for predawn attacks, fought as rearguards (once, in a scene straight out of Beau Geste, leaving straw dummies in the parapets before pulling out in a gale), escorted supply columns, and manned the most exposed blockhouses. They also did something else.

As Paul Preston wrote, “Despite the fierce discipline in other matters, no limits were put by Millan Astray and Franco on the atrocities which were committed against the Moorish villages which [the Legion] attacked.” One Legionnaire’s idea of a gift to a Spanish duchess who sent them medical supplies was a basket of roses containing two severed Moroccan heads.

Leaning toward evacuating Morocco, Spain’s dictator of the 1920s, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, was left in no doubt where Legionnaires stood when he visited a base. He was greeted with banners crying “Attack” and “The Legion never retreats,” served a meal of nothing but eggs (huevos, which in Spanish carries a connotation regarding one’s manhood), and was howled down when he tried to speak.

Millan Astray’s characteristically uncontrollable outspokenness led to his forced resignation in November 1922. His successor, Lt. Col. Rafael de Valenzuela, soon died in action, shot through the head as he led a charge, pistol in hand. Franco became the new commander on June 9, 1923.

Fighting “From Boulder to Boulder”

Franco argued successfully for a landing behind rebel lines at Alhucemas Bay. This the Legion did on September 8, 1925. They secured the beachhead, then held off two nights of counterattacks as regular troops landed. A Berber shell buried Franco in the sand and he had to be hurriedly dug out. After two weeks, the Spanish forces, the Legion again in the vanguard, struck inland. The fighting, with Franco in the thick of it, “was carried on literally from boulder-to-boulder every step of the way, with sudden charges and countercharges and numerous hand-to-hand encounters,” according to David Woolman. Four Laureate Crosses of St. Ferdinand were earned by Legionnaires in 10 days, compared to seven in three years during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s.

The Legion wiped out the last defenders in their mountain caves with mortar fire and grenades and on October 2, 1925, participated in the capture and burning of the rebel capital of Adjir. Millan Astray returned to command of the Legion in the war’s waning months. Within 24 days he lost his left arm when a bullet wound turned gangrenous and had his right eye shot through by a sniper. On May 26, 1926, the Berber leader Abd el-Krim prudently surrendered to French forces advancing from their southern zone.

Fighting in Mainland Spain

In the Riff War the Spanish Foreign Legion lost 1,987 killed (including 116 officers) and 6,094 wounded. The Legion’s worst fighting lay ahead, as Spain slid toward civil war in the chaos of the 1931 Republic.

The Legion fought for the first time in mainland Spain during October 1934, when the miners in the northern Austurias rose up, using dynamite to drive off Civil Guard and regular troops. At the order of Franco, now Army Chief of Staff, the Legion stormed into the Austurias and “razed it as if it were a rebellious Moroccan village” in the angry, if accurate, words of communist Dolores Ibarruri, also known as La Pasionaria.

Two years later, it was the Legion’s turn to rebel. On July 17, 1936, the Foreign Legion in Morocco rallied to its former commander, Franco, as he and other generals tried to overthrow the left-wing Popular Front government. After Franco’s appeal to Hitler, the Legion was flown to the mainland in German transports. So swift was the movement that officers had to grab Michelin road maps at gas stations to find their way to Madrid. The Legion’s drive on the capital was stopped just short by the International Brigades defending the University City complex. Fighting against Soviet-supplied tanks, Legionnaires invented the gasoline-in-a-bottle incendiary later called the Molotov cocktail.

The Civil War’s Fiercest Battles

With new enlistments more than doubling its size, the Legionnaires went on to fight as shock troops in the Civil War’s fiercest battles—Irun, Jarama, Guadalajara, Teruel, Brunete, and Ebro River—suffering 7,645 killed and 28,972 wounded.

The Legion had its largest foreign enlistment during the Civil War, reflecting the nature of a more political and ideological conflict than the Riff War. In the Legion were thousands of Portuguese, 500 French forming a Joan of Arc Battalion, 600 leftovers from a defunct Fascist movement in Ireland, plus South Americans, Germans, White Russians, Eastern Europeans, and a half-dozen British.

In the ranks were Georges Kozma, a Hungarian former priest-missionary expelled for consorting with African women, fatally wounded in March 1937; Jesuit priest Fernando Huidobro Polanco, who served as a company chaplain before being killed at the Madrid front in December 1937, and later improbably pushed for sainthood; and a flamboyant undertaker from Sydney, Australia, Nugent Bull, who would die fighting with the RAF in World War II. There was Domingo Piris Berrocal, who enlisted on the first day in 1920, fought from Alhucemas Bay to Teruel and Ebro, eventually retiring in 1961 as the Legion’s second-ranking officer; two former British Army lieutenants, Noel Fitzpatrick and Gilbert Nangle, the first non-Spaniards to be directly commissioned as captains in the Legion (both returned to Britain to serve in World War II, but Nangle did not survive); and Serge Tchige, a former Czarist naval officer killed by a shell fired by a Soviet tank.

When Romantic Fatalism Becomes Realism

There was 18-year-old Czech Frantisek Shostek, who robbed his father’s safe in Prague but was destitute when he enlisted then was caught trying to desert; and Ionel Motza and Vasile Marin of the Fascist, viciously anti-Semitic Romanian Iron Guards, both killed. There was also Frank Thomas, a traveling salesman from Cardiff, Wales, who was an avid reader of Beau Geste and whose “romantic fatalism became realism” (his own phrase) after being wounded. He snuck out with the repatriating Irish to immediately write a memoir that would not be published until 1998.

Two of the seven Laureate Crosses of St. Ferdinand awarded to Legionnaires in the Civil War were earned by Corporal Renato Zanardo at the Argon front on March 11, 1938, and Lieutenant Guisseppe Borghesse de Borbon y Parma at the Ebro on September 22, 1938. His hand blown off, Corporal Zanardo nevertheless drove his tank to the aid of another one under attack, then drove it for almost four miles back to his lines. Wounded leading an assault, Lieutenant Borghesse de Borbon single-handedly killed a machine-gun crew, used the gun to provide cover for his men, threw grenades, and fired his pistol at oncoming Loyalists. Then he was fatally wounded in the chest by a grenade fragment, but shouted encouragement to his men until he died.

Extreme Bravery, Astonishing Brutality

Along with the extreme bravery came astonishing brutality. In the opening days of the war, Legionnaires ran wild through the working-class district of Seville with knives. Later, in what became the most notorious Rebel atrocity until Guernica, they massacred 4,000 Loyalists at Badajoz, shooting and knifing in the streets and machine-gunning at the bull ring. Frank Thomas saw his company commander, Lieutenant Dmitri Ivanoff—a giant Bulgarian who had murdered a Spanish journalist for exposing Legion atrocities in the Austurias—mow down 25 prisoners with his submachine gun. (Ivanoff was killed the same day when a shell blew off his legs. “Grim retribution,” Thomas called it.)

Some of this astonishing ruthlessness could be directed toward its own men, as three unusual Legionnaires who were fortunate enough to survive discovered.

Peter Kemp, a Cambridge law graduate, reluctantly carried out the order to execute a countryman in the International Brigades. Later he discovered that the firing squad had orders to shoot him too if he had not.

Guy Stuart Castle: American Legionnaire

The only American Legionnaire in the Civil War, Guy Stuart Castle, tried to desert and it took State Department pressure to save him from the firing squad. He would survive Guadalcanal as well and died in 1965.

Eugenio Calvo, a communist on the run from Franco’s secret police, came upon a Legion recruiting office and enlisted in order to reach the front and then desert. He succeeded, after first having to watch the execution of five other communists with the same idea.

The Legion’s last serious fighting, from November 1957 to February 1958, was repelling a liberation army’s invasion of Spain’s Spanish Sahara colony. Fifty-five Legionnaires died and 74 were wounded, most in two days of close-quarter and hand-to-hand fighting in the dunes. It was here that Brigade Sergeant Fransisco Fadrique Castromonte and Legionnaire Juan Maderal Oleaga were awarded the last Laureate Crosses of St. Ferdinand to date—posthumously. To cover wounded being carried away, they stood firing into oncoming rebels until they fell; more than 30 bodies were found around them.

The Legion evacuated the Moroccan Protectorate in February 1961, and the Spanish Sahara in February 1976. The Legion’s most active service of late has been in the unusual role of United Nations peacekeeper in Central America, the former Yugoslavia, and Africa. Today, its most exotic recent member is a Sikh from India and its main foreign source of enlistees is Africa. The 7,000-strong Spanish Foreign Legion garrisons two fortress enclaves on the Moroccan coast, Melilla and Ceuta. Held by Spain for more than 500 years, they are duly considered Spanish soil. Should Spain ever give them up, then perhaps the Legion that shouted and sang about death will itself finally die.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments