By John Brown

The ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu wrote, “Go forth to the enemy’s positions to which he must race. Race forth where he does not expect it.” There is no record that Adolf Hitler ever studied Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, but he certainly understood many of its principles, at least during the early phases of World War II.

After Hitler bloodlessly annexed his homeland of Austria in March 1938 and bluffed the Czechs, French, and British into giving him the Sudetenland in October, in January 1939 his armies invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia. In May 1939, he signed a “Pact of Steel” with Italy, and in August concluded a cynical nonagression pact with Soviet Russia. Then, on September 1, he launched his first blitzkrieg against Poland, causing France and Britain to declare war on the aggressor.

[text_ad]

Blitzkrieg, or “lightning war,” was an unprecedented war of movement using modern technology and methods in the form of paratroops, gliders, fast-moving tanks, mobile infantry and artillery, and aircraft, particularly the dive bomber. It was a devastating form of combined-arms warfare with an assault spearheaded by panzer (tank) divisions whose firepower and shock were magnified by their accompanying Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers.

Poland was the testing ground for blitzkrieg. It gave the Wehrmacht the opportunity of trying out and making improvements in this new type of warfare. When it proved sucessful, Hitler turned his attention from east to west.

Germany’s next victims were Norway and Denmark, both invaded on April 9, 1940, in blitzkrieg-style assaults named Operation Weserübung. The countries held out briefly, then capitulated.

The Cut of the Sickle

With European nations folding in the face of German onslaughts, the stage was then set for the pièce de résistance: Plan Sichelschnitt (the cut of the sickle), the blueprint for a blitzkrieg against Germany’s old and bitter enemy, France.

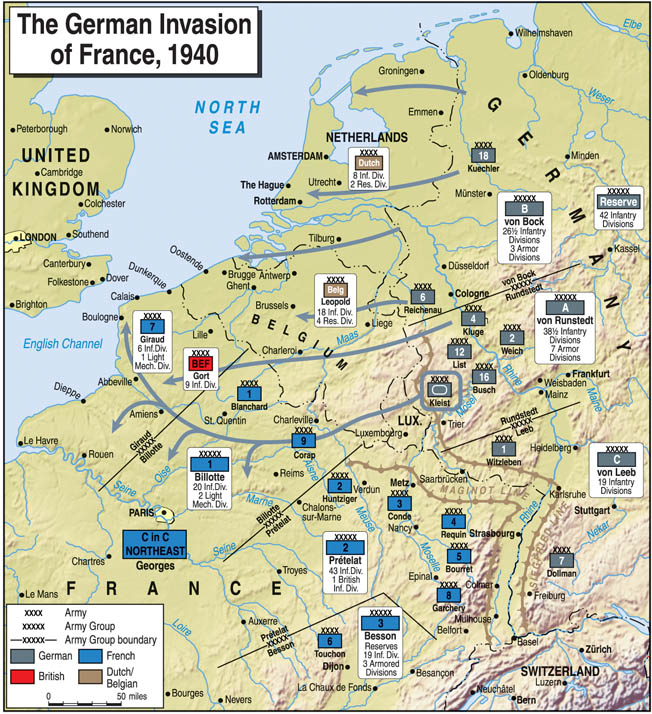

At this time, Allied military strength consisted of the French with 94 divisions, the Belgians with 22, the Dutch 10, and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) also with 10—a total of 136 divisions. The Allies had about 3,000 tanks, the Germans just over 2,400, but with better-trained crews and equipped with radios. In artillery the French were far superior to the Germans—11,200 guns of various sizes against the Germans’ 7,700.

In the air the Germans dominated, able to deploy 3,000 aircraft. Unfortunately for the Allies, the education of most French military commanders had ended in 1918—they were “unable to think beyond the firm belief in a rigid linear defense.” This included the supreme commander of French land forces, General Maurice-Gustav Gamelin. Neither Gamelin nor his four immediate aides, the aging Generals Henri Bineau, Alphonse Georges, Maxim Weygand, and Gaston Billotte, had any concept of armored strategy and scattered their forces in small pockets in an effort to plug holes in the national defenses.

The German plan of attack was a reworked version of the failed Schlieffen Plan of 1914, brought up to date by Generals Erich von Manstein, Heinz Guderian, Erwin Rommel, and others. It laid out that the main attack—by Army Group A of 45 divisions including seven panzer divisions and commanded by General Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt—would crash through the forested hills of the Ardennes, which the Allies believed to be “impenetrable to tanks and heavy vehicles.” Army Group A would then cross the River Meuse into northen France on a front from Dinant to Sedan.

North of Army Group A, Army Group B’s 29 divisions (including three panzer divisions), commanded by General Fedor von Bock, would draw off the Allies to the north and hold them there, thus securing von Rundstedt’s right flank. To the south of Army Group A, opposite the Maginot Line, General von Leeb’s Army Group C (19 divisions) would prevent French reinforcements from moving up from the Maginot Line to attack von Rundstedt’s left flank. The operation was set to begin on May 10, 1940.

The Brandenburgers Pave the Way

Prior to or at the beginning of “Blitzkrieg West,” a number of special operations paved the way for the panzers. Most of the special operations were carried out by paracommandos of the special forces regiment Brandenburg.

Several days before the attack in the West began, German commandos posing as tourists crossed the border into Luxembourg and, at 4 o’clock on the morning of the attack, they occupied vital road junctions and bridges and kept them open for the panzers.

Three bridges provided entry into the Low Countries for the panzers, at Gennap, Roermond, and Stavelot, and it was vital they remained open. They were known to be mined, and ruses were necessary to prevent them from being blown.

Everything fell on the shoulders of a second lieutenant named Walther of the Brandenburgers, who was ordered to seize the major railway bridge at Gennap, located on the Meuse between the German province of Westphalia and the Dutch province of Brabant, and to hold it intact until the panzers arrived.

With their weapons hidden, Walther and several of his commandos, dressed in uniforms of the Royal Dutch gendarmerie, and with seven other commandos acting the part of prisoners, arrived at the guardpost on the bridge 10 minutes before the panzer assault was to begin on May 10.

At a signal from Walther, the “prisoners” attacked the guardpost and firing broke out, wounding three of the commandos. The guardpost was captured, and Walther and two of his commandos walked along the bridge to the guardpost at the other end. The guards there, seeing three men in Dutch uniforms coming toward them, hesitated, and Walther, now close enough, tossed a grenade at them and quickly took possession of the detonator set to fire the explosives that would destroy the bridge.

At this point the first panzers arrived and began to cross the bridge. Walther ran toward them, but the tankmen, unaware of the commandos’ mission, took him to be a Dutch soldier and opened fire, severely wounding him. He survived and was awarded the Iron Cross for his part in the mission.

Similar ruses were used to secure the other two bridges.

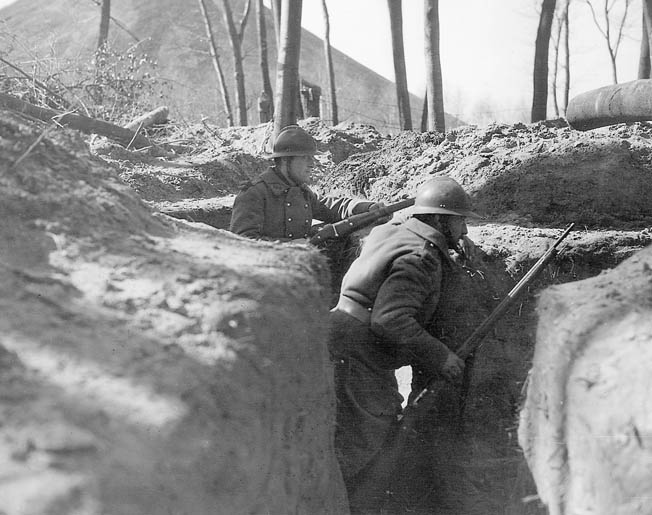

With the first faint light of dawn over Belgium, a reinforced platoon, designated “Granite,” comprising two officers, 73 Brandenburger paracommandos, and 11 pilots, all under the command of 23-year-old Lieutenant Rudolf Witzig, landed in gliders on the roof of the modern fortress complex of Eben Emael.

The fortress guarded the juncture of the Albert Canal and the River Maas (Meuse) on the Belgian/Dutch border just south of Maastricht. In addition to their personal weapons, the attack force carried flamethrowers, bangalore torpedoes to blast through barbed wire, and 56 highly destructive hollow-charge bombs capable of breaking through the defensive armor of the fortress.

At Eben Emael, Belgian Major Jean Jottrand, alerted by a nationwide radio broadcast that German troops were crossing the frontier, had 780 troops of the garrison at action stations awaiting an attack on the ground, not from the sky. When Jottrand’s men realized what was happening, it was too late—the gliders had landed on the roof of the fortress and German paracommandos were racing for their objectives.

Several of them, carrying a 110-pound hollow-charge bomb, raced unseen to one of the major artillery emplacements, placed the charge against the base, set the fuse, and ran for safety before an explosion shook the fort. The explosion blew the 120mm gun in the emplacement off its mounts, and it fell into the shaft below it. Every defender in the emplacement was killed.

Other paracommandos set a 25-pound hollow-charge bomb against the steel doors of a 75mm gun emplacement that, on detonation, blew the gun across the casemate, wrecking the interior. The Germans then went in through the large hole torn by the blast in the casemate wall and deeper into the interior of the fort, spraying everything and everyone with their submachine guns.

Paracommandos were systematically blasting gun casemates all over the fortress roof, one of them knocking out the electric power on the first subterranean level, plunging it into darkness and leaving the Belgian defenders shocked and confused.

The finale of the assault came when paracommandos blew in the steel doors of Jottrand’s redoubt in the deepest part of the fort and a bugle sounded the call for surrender.

The ultimate credit for the success of the operation at Eben Emael goes to the German Führer, Adolf Hitler, who came up with the idea of using gliders and the new hollow charges and planned the operation against the protests of most of his generals, who argued for a frontal assault on the fortress that would have taken days, if not weeks, of fighting to secure. The taking of Eben Emael in just a few hours was the key to starting the blitzkrieg in the West.

At the same time as the paracommandos were landing on the roof of Eben Emael, soldiers of the Waffen-SS Infantry Regiment Grossdeutschland landed behind the Belgians west of Martelange, glider-borne troops landed around Rotterdam and the Hague, and more landed from aircraft at the besieged airfield of Waalhaven.

Panzer Breakthrough in the Ardennes

Throughout the morning, Heinkel bombers dropped their loads on railway junctions and air bases in northeastern France, and fighters machine-gunned the streets of the Hague and other cities. The main purpose of these activities was to draw the French and British forces’ attention away from the Ardennes and the German forces coming through it.

General Georg von Kuchler’s Eighteenth Army of Army Group B, spearheaded by the 9th Panzer Division, struck across the Dutch border and headed straight for Rotterdam. South of him, General Walther von Reichenau’s Sixth Army of Army Group B, led by the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions, crossed the Maastricht bridges and joined airborne units that had landed alongside key bridges over the canal west of Maastricht.

Believing this to be the main attack, General Gamelin immediately sent his best troops—the First, Seventh, and Ninth Armies and the British Expeditionary Force, under the overall command of General Billotte—to meet what he thought was the spearhead of the German attack in Belgium. General Giraud, commanding the Seventh Army, raced up through Belgium into southern Holland, taking with him the best of France’s armored units and most of the available Allied air cover.

In Holland, the Dutch flooded the land and fought back against the Germans as best they could, but by May 12 the situation was desperate. The Germans had reached the shore of the Zuyder Zee and, to the south, the 9th Panzer Division was linking up with the paratroops holding the bridge at Moerdijk. The Dutch Army was forced back to cover the cities of Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and Utrecht, and the Dutch Air Force was reduced to a single bomber.

Meanwhile, Rundstedt’s Army Group A, led by the 5th and 7th Panzer Divisions (the 7th Panzer was commanded by Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel) of the Fourth Army, was crashing through the “impassable” Ardennes. The Fourth Army drove through Luxembourg and Belgium, scattering all opposition, while General Georg-Hans Reinhardt’s 6th and 8th Panzer Divisions and Guderian’s 1st, 2nd, and 10th Panzer Divisions headed quickly for Sedan and Montherme.

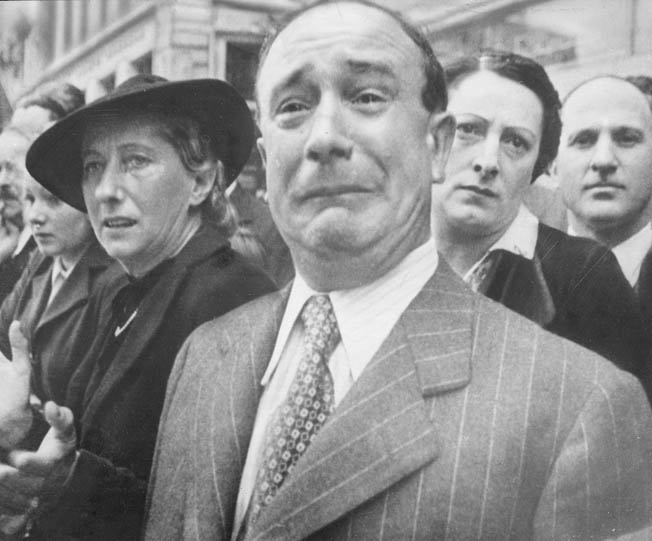

Like a flood from a broken dam, the headlong advance of the panzers could not be halted, and there were rumors of German tanks everywhere. Many French units fled in panic, and thousands of civilians took to the roads of France. To the north, Giraud’s French Seventh Army was being pushed in disarray from Antwerp, which the Belgians were desperately trying to hang on to, and the French First Army was near collapse.

On May 12, Rommel and his tanks, after some sharp fighting with French cavalry, arrived in the evening on the heels of the retreating cavalry at the bridge over the River Meuse at Yvoir. When his armored cars tried to rush the bridge, a Belgian officer destroyed the span with explosive charges.

The motorized infantry brigade established control of the east side of the river and during the night found an old weir connecting the east bank with an island in midstream. On the other side of the island were old lock gates and, using these and the weir, several companies of troops crossed the river and establishd themselves on the west bank. During the next two days, Rommel established two bridgeheads across the Meuse.

While this was happening, Guderian had swung his three panzer divisions westward, converging with Reinhardt’s two divisions from the drive on Montherme and, with Hermann Hoth’s two divisions from near Dinant, reached the Meuse just west of the fortress city of Sedan on May 12. They occupied its northern bank and captured Sedan. Fearing a German outflanking movement to isolate them, the Allies retreated from the east bank of the Meuse as far north as Dinant in Belgium.

This area of the river had been heavily bombed and strafed, and on the 13th Guderian, who had established his corps headquarters at La Chapelle, was with the first of his mobile infantry when they crossed the Meuse in rubber boats. A bridge was quickly thrown across, and tanks began crossing. French resistance began to collapse.

On May 13, the open city of Rotterdam was bombed. Many civilians were killed and, in fear of more terror bombing of cities and towns, the Dutch royal family fled to England; the government surrendered on the 14th. Casualties in the Dutch Army reached some 25 percent of its strength.

To the south the 1st Panzer Division had fought its way up the southern escarpment of the Meuse, followed by the 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions. The 1st Panzer established a bridgehead on the south bank of the river that stretched for three miles. The French 7th Tank Battalion and 3rd Armored Division counterattacked, but they were easily dispersed by the panzers. The Allies then assembled every available tactical bomber for an attack on the bridgehead, but nearly all the planes were obsolete. German antiaircraft fire was deadly, and 150 of the attacking planes were destroyed.

On the afternoon of May 15, Guderian, leaving the 10th Panzer behind to guard the Meuse bridgeheads until relief arrived, led his 1st and 2nd Panzer Divisions west and the following day reached Marle and Dercy, 55 miles west of Sedan. At Dercy he took several hundred French soldiers prisoner and almost without incident captured a tank company from Colonel Charles de Gaulle’s 4th Armored Division (see WWII Quarterly, Winter 2014).

To the north, Rommel and his 7th Panzer Division had crossed the Meuse at dawn on May 14 and struck the French Ninth Army, destroying its supplies and disrupting communications; by nightfall 7th Panzer was four miles west of the river with the 5th Panzer Division close behind. The French fell back before the panzers and, when the French 1st Armored Division attempted to cover the rear of the retreat, the two panzer divisions destroyed almost all of its tanks. The French withdrawal became a rout as the troops panicked in the face of fast-moving armor and Stuka attacks.

On May 15, General Gamelin reported to French Defense Minister Edouard Daladier that he had no reserves left and that the French Army was virtually finished. He was replaced as supreme commander by 73-year-old General Weygand, but the new appointment achieved nothing.

A Strong British Counterattack

Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division had reached Cambrai on the evening of May 18, and there he paused the division for rest and to bring up supplies. The following night he moved on toward Arras, where the British headquarters was being evacuated.

Lord John Gort, commander of the BEF, clearly realized that the BEF’s position was perilous. Seven of his divisions were arrayed along the River Scheldt, and even if they could be moved their withdrawal would leave another gap through which the Germans could penetrate. Strong German forces were moving around the British right flank between Arras and the Somme, and Gort had only four days of supplies and enough ammunition for one more battle.

On May 19, he was visited by General Sir Edmund Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, who told him that only a concerted attack in the direction of Amiens, supported if possible by the French, would prevent the BEF from being surrounded and either captured or wiped out.

Gort had two divisions in reserve, the 50th and the 5th. If he could get cooperation from General Weygand in attacking from the south, he might at least keep open a corridor to the coast. Ironside himself found General Billotte and General Georges Blanchard, commander of the French First Army, at Billotte’s headquarters; both men were in a state of acute nervous depression. Taking hold of Billotte, Ironside shook him and told him, “You must make a plan. Attack at once to the south, towards Amiens, with all your forces.”

On May 20, the British First Army Tank Brigade and the 5th Division were ordered to Vimy, north of Arras, to join up with the 50th Northumbrian Division for an attack that would aid the garrison at Arras and attempt to hold the German advance. The group was commanded by Maj. Gen. Harold Franklyn, commander of the 5th Division, and was code-named Frankforce.

At dawn the next day, the Tank Brigade consisted of only 58 Mark I infantry tanks and 16 Mark II “Matildas.” Of the 50th Northumbrian Division, only the 151st Brigade consisting of three Durham Light Infantry territorial battalions was available to support the attacking tank force in its first sweep toward Arras. It would then be joined by the 13th Brigade of the 5th Division. The French 3rd Division of the Cavalry Corps was to support the British right flank with its battered Somua S35 medium tanks.

The attack force was commanded by British Maj. Gen. Giffard Martel and consisted of 74 tanks and less than 3,500 men.

Warned by intelligence of British and French tank movements in the Vimy area, Rommel began on May 21 to move his 7th Panzer Division around the west flank of Arras, while the 5th Panzer Division deployed to the east. They were still to the south of the town when Martel’s tanks attacked.

The tanks, unsupported by infantry, crossed the River Scarpe and took the German-held village of Duisans. Joined by several companies of the 8th Durham Light Infantry, Martel went on to take Warlus and Berneville in the face of opposition by Rommel’s 7th Rifle Regiment and part of the SS Division Totenkopf.

But at Berneville the Germans, at first taken aback by the bold British thrust, began to rally. Machine guns and mortars cut down almost half of the Durhams and a Stuka raid made the rest take cover. Only the Matilda tanks kept going. As they approached the village of Wailly spraying machine-gun bullets, German artillerymen began to desert their howitzers.

Other British tanks had crossed the Arras-Doullens road and were knocking out German vehicles that had jammed the road in panic. Rommel himself ran from gun to gun, giving his gunners specific targets. He reported afterward that morale was suddenly very low.

The British force drove 10 miles into the German lines, capturing four villages, destroying a motor transport column and an antitank battery. But by now Rommel had managed to build up a line of guns from Neuville to Wailly, which sealed off the Matildas. Pounded by the guns and by Stuka dive bombers, the British beat a fighting retreat. German casualties were around 300 with 400 taken prisoner. Twenty German tanks were destroyed, and 46 British tanks were lost. The battle at Arras was a limited tactical success but worth the losses in terms of strategic and psychological advantages.

The Halt Order From the Fuhrer

While fighting was going on at Arras, Guderian and his panzer corps were moving up the coast. By May 22, they had cut off Boulogne and by the next day Calais, while forward units were pushing on to the Aa Canal, only 10 miles from Dunkirk. The British forces in and around Arras were 46 miles away, cut off, and soon would be forced to capitulate.

But then, on May 24, came the “Führer Order.” Any further advance beyond the Aa was forbidden.

Hitler and the high command, amazed at the ease with which the Meuse had been crossed, expected Allied counterstrokes against the flanks of the panzers, which had outdistanced their infantry divisions, and feared the panzers could be cut off. Therefore, the “Führer Order” was issued, telling the panzer commanders to halt at the Aa Canal (12 miles from Dunkirk) for three days to enable the infantry to catch up and form a flank shield for the tanks.

Guderian ignored the order to halt. He was summoned to a meeting with his immediate superior, General Paul Ludwig von Kleist, who “tore a strip off him” for disobeying the order. Guderian asked to be relieved of his command, and von Kleist agreed. Guderian then sent a radio message to Commander in Chief Rundstedt telling him what had happened and received a reply to stay where he was.

Later that day, May 17, Guderian was told that his resignation would not be accepted and that the order to stop the advance had come from Hitler himself and must be obeyed. But “reconnaissance in force” could continue to be carried out by the panzers. Guderian interpreted this as an invitation to carry on his advance.

On the move again, Guderian and his 1st and 2nd Panzers reached St. Quentin and crossed the Oise and the Somme near Peronne and on May 19 drove across the World War I Somme battlefields. There, a brief attack by Colonel Charles de Gaulle’s 4th Armored Division was beaten off, but no real effort was made to strike at the rapidly moving German armor. What was left of the French troops in Belgium were withdrawn in an attempt to flank the Germans to the north while Weygand’s main force lined the Somme on the south side. The moves were in vain.

Operation Dynamo: The Retreat at Dunkirk

On May 20, the leading elements of the 2nd Panzer Division reached Abbeville on the French coast, trapping the BEF and blocking it from further withdrawal into France.

By this time, Calais, first choice as an evacuation point for the British, was under siege and Lord Gort began implementing an emergency plan—the expeditionary force would withdraw to the coast at Dunkirk, the closest point to England, for evacuation by sea.

In disarray, individual British units retreated to the coast and moved through the burning rubble of Dunkirk onto the beaches, exhausted from days of desperate fighting as they retreated in a shrinking perimeter. Supplies and rations were running out, and on the beaches the soldiers, hungry and dejected, waited under a hail of shells and bombs and hoped that rescue would arrive before the Germans did.

North of Dunkirk, the Belgian Army was pulling back and on the verge of surrender. Guderian’s panzer corps had taken Boulogne and by nightfall on May 25 was within 20 miles of Dunkirk.

In England, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, Royal Navy Flag Officer, Dover, was gathering together a motley fleet of coastal ferries, coasters, barges, lighters, tugs, launches—any craft able to cross the English Channel to Dunkirk. He also had a small flotilla of destroyers to protect the evacuation craft, cover their crossings, and provide counter bombardment against the batteries on the French shore.

The evacuation, code-named Operation Dynamo, was sheduled to begin at 7 pm on May 26, but before that ships of the Royal Navy had made the crossing and brought back some 28,000 soldiers. Their officers reported that Dunkirk was a shambles and the dry docks, harbor installations, and miles of quays that had once made Dunkirk the third largest port in France were now mangled masses of burning wreckage, useless for evacuation purposes.

The East and West Moles remained, the West Mole projecting from the oil-storage area would soon be unusable and the East Mole was little more than a long, narrow plank extending nearly a mile out to sea. The beaches were the only means of evacuation.

On the early morning of May 27, Hitler ordered his tanks to resume their attacks. Two task forces were redeployed; one, including Guderian’s three panzer divisions, was ordered east along the coast from Gravelines and the other to advance northeast to Armentières to drive a wedge between the British and French forces. The panzers would link up with the Sixth Army, which was advancing from the east, and with the help of the Luftwaffe would overwhelm all resistance.

However, the panzers moved too late, and the British fought desperately all through the 27th, defending the bridgehead around Dunkirk and enabling the British divisions and the greater part of 5th Corps of the French First Army to get inside the perimeter.

During the battle, the 2nd Royal Norfolks, 8th Lancashire Fusiliers, and 1st Royal Scots were forced to surrender at Le Paradis, where elements of the SS massacred the survivors of the 2nd Royal Norfolks while they claimed the protection of a white flag. The SS were about to massacre the others when stopped by a senior Wehrmacht officer.

Not far away, at Wormhoudt, 85 men of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, Cheshire Regiment, and Royal Artillery were similarly slaughtered by the SS.

While the BEF continued to pull back, during May 27 General Franklyn and his battalion of the Durham Light Infantry and his surviving tanks linked up with Maj. Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division and others to plug the gap in the Belgian defenses, but Armentières had to be abandoned to the panzers.

By midnight on the 27th, 7,700 men had been evacuated from Dunkirk. It was anticipated in London that no more than 45,000 could be saved. That night, Captain W. Tennant, the senior naval officer in Dunkirk, having seen the unsuitability of the East Mole for mooring large ships, sent a signal: “Please send every available craft to beaches east of Dunkirk immediately. Evacuation is problematical.”

338,226 Soldiers Rescued

At his base in Dover, Admiral Ramsay was struggling with the problem of how to rescue the troops. The shortest crossing to Dunkirk could only be used under cover of night, and other possible routes were ruled out by the danger of mines. The only route possible in daylight was 87 miles long, from Dover to the North Goodwin Light, east to the Kwinte Buoy, and back to Dunkirk. Some 6,000 troops were rescued by the Royal Navy from the beaches and 11,900 from the mole during May 28.

By now, communications in the armies had broken down, and each commander had to act on his own initiative. But by nightfall on May 28, the BEF had redeployed in good order, providing protection on all flanks.

In the French First Army, however, there was utter confusion and a sense of defeatism, but the III Corps and some cavalry units continued to give some support north of the British, and two divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. Jean-Baptiste Molinié kept fighting in spite of low morale. By the end of May 29, the front line was nowhere more than five miles from the sea, and by the next day the perimeter of the bridgehead was reduced to 32 miles. The French held 11 miles of it and the British the rest.

Ramsay sent a continuous stream of small ships to Dunkirk via the North Goodwin Light and Kwinte Buoy route and opened up a route through mined areas, raising the number of soldiers rescued on May 29 to some 53,800.

As soon as secrecy was lifted and news of Operation Dynamo broke at 6 pm on May 31, many private boat owners and yachtsmen set sail from the south coast of England. This huge civilian effort brought back a further 26,000 soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk. To provide more ferrying craft, small river boats were tied in strings behind larger craft and towed over empty, but this proved disastrous as the light frames of the river boats could not stand up to vigorous towing. But “drifters,” believed to be capable of carrying 100 men, limped back with 250 men on board.

By the end of the 31st, the perimeter of the British beachhead was no more than 10 miles wide and five miles deep, but by sunset on June 1 and dawn next day, most of the British had been evacuated.

On the night of June 2, the remaining 4,000 British and more than 20,000 others were evacuated. The next night, more than 26,000 troops, mostly French, were evacuated, although many, exhausted and beaten, refused to embark, preferring captivity to further warfare.

During the evacuation, the 21 understrength squadrons of 11 Group of the RAF flew a total of 4,822 hours in support of the evacuation, destroying 258 German aircraft and damaging 119 more for the loss of 87 of their own.

When Dunkirk’s remaining defenders surrendered on the morning of June 4, a total of 338,226 soldiers had been saved.They left behind a huge assortment of tanks, vehicles, and guns.

During the final stages of the evacuation at Dunkirk, General Weygand tried to organize a new defensive position in northern France, but the situation was desperate. The Belgians and Dutch had been defeated, the British, except for two divisions, had been driven from the Continent, and the French Army had lost 370,000 dead, wounded, or taken prisoner, together with three quarters of its tanks and most of its motor transport.

The morale of the army, and of the French nation itself, was close to rock bottom. The Germans had outflanked the fortifications of the Maginot Line by attacking through Belgium and Holland and were now threatening to swoop down from the north and overrun all of France. Hitler said, “Our most dangerous enemy is Britain, but we must first beat her continental soldier, France.”

Endgame in France

For the next phase of his attack on France, Hitler could call on 143 divisions of battle-hardened troops, while Weygand could muster only 65 divisions, including the 17 divisions still defending the Maginot Line. He also had the two British divisions, the 51st Highland Division and the 1st Armored Division, which had been stranded in France after the evacuation at Dunkirk.

Weygand, who had never commanded troops in combat or made any effort to absorb the new concepts of mobile, armored warfare, decided to make a stand behind the line of the Somme and Aisne Rivers stretching southwestward 225 miles from the English Channel to the northern end of the Maginot Line at Longuyon. Behind this line he organized a network of well-dug-in positions and natural tank obstacles, and behind these he positioned his infantry reserves and scattered tank units.

As they had curled around the Allied forces at Dunkirk, the panzers had seized five bridgeheads across the lower Somme. When the final battle for France began, these advanced German positions were poised like daggers against the heart of France.

General von Bock’s Army Group B was next to the Channel. On June 5 it drove across the Somme and raced for the Seine. Four days later, General Rundstedt’s Army Group A, led by Guderian’s panzers, attacked east of Paris, driving a wedge between the two French Army groups fighting there and pinning one of them against the Maginot Line.

One of his armies moved onto the plain of Picardy on the 5th and ran into heavy French resistance, which threatened to overrun its headquarters. But General Rommel and his 7th Panzer Division came to the rescue.

In a daring attack through a mile of swampland, Rommel drove back the French and, with the rescued army group, by nightfall was eight miles beyond the Somme. On the following day, they were 12 miles farther on and driving hard for the Seine. The French front had been torn wide open.

In the next few days, Bock swung his army group westward toward the coast, trapping part of the British 51st Division and a large French force at the seaport of St. Valery-en-Caux. The Royal Navy tried to evacuate them, but a combination of heavy gunfire from the shore and a thick fog prevented the ships from getting into the port. The troops surrendered. More than 40,000 were taken prisoner.

The German armies regrouped to complete the conquest of France. Bock’s Army Group B was on the left flank, Leeb’s Army Group C on the right, and Rundstedt’s Army Group A again in the center. The French also tried to regroup on the Somme and the Aisne Rivers, with 40 shaky divisions attempting to hold a 225-mile front above Paris.

The new blitzkrieg began on June 5, and by June 9 Army Group B was on the Seine west of Paris and General Weygand had ordered French Army Group 3 to withdraw to the Seine. At the same time, Rundstedt’s Army Group A blasted its way through the French at Châlons and surged eastward. The French were now in headlong retreat, and on June 13 Paris was declared an open city. The Germans marched in the next day.

German forces fanned out west, south, and east, wheeling to pin the remnants of the French armies behind the Maginot Line. On June 17, Marshal Philippe Pétain replaced Paul Reynaud as president of France, and General de Gaulle flew to Britain to organize Free French forces and declare a French government in exile. On June 21, a massive force of 32 Italian divisions attacked in the south but was checked by six French alpine divisions.

Pétain and Weygand sought an armistice. In the railway coach where the armistice of 1918 was signed, Hitler dictated his terms. The surrender was signed on June 22 and came into effect at midnight, June 25.

An Allied Rout

Blitzkrieg West cost the Germans 27,074 dead, 111,034 wounded, and 18,384 missing. French losses for the six-week campaign were an estimated 90,000 dead, 200,000 wounded, and 1,900,000 prisoners and missing. Total British casualties were 68,111, Belgian 23,350, and Dutch 9,779. The French Air Force lost more than 560 aircraft in combat, the RAF 931, with 477 of them precious fighters. The Luftwaffe lost 1,284 aircraft.

In less than six weeks, France had been utterly routed by the blitzkrieg. The size of the achievement was measured by Guderian in an address to his victorious troops: “We have covered a good 400 miles since crossing the German border; we have reached the Channel coast and the Atlantic Ocean….

“You have thrust through the Belgian fortifications, forced a passage of the Meuse, broken the Maginot Line extension in the memorable Battle of Sedan, captured the important heights at Stonne and then, without halt, fought your way through St. Quentin and Peronne to the lower Somme at Amiens and Abbeville. You have set the crown on your achievements by the capture of the sea fortresses at Boulogne and Calais…. Germany is proud of her panzer divisions and I am happy to be your commander.” It would be four years before the Allies set foot again on French soil, but retribution was coming.

There was a saying about the Bourbon kings of France: They learn nothing and forget nothing. Seems that was also passed down to the leaders of the Republic. Despite the examples of the Franco-Prussian War and WW I, the French military, with few exceptions like De Gaulle, learned nothing. However, it should also be noted that our military and political leaders seem to have learned little from Korea and Vietnam as they keep trying a do over in order to get a different result.

Hitler was very good at surprise attacks on innocent, unarmed civilians, and also surprise attacks on armed countries which were completely unexpecting to be attacked.

Once he ran into armed strength, however, he was not so successful.

In fact, he was completely and totally overwhelmed, although it took much manpower and millions of dollars to do it.

Such a sad commentary when one sick individual, with a twisted, criminal mind, could rise up to wreak his madness on a world full of peace-loving, complacent people.

It was eye-opening to me that the final tallies of the dead, wounded, and missing that the French, and British, at al did give such a good account of themselves at the tactical level.

They were good soldiers, after all.

The point that the Wehrmacht stopped a slaughter by the SS was beyond impressive re that there are still found honorable forces in beastly situations.

Great article in all respects.

.

War is not about who were right, but who were left….