By Jason Abady

In April 1942, a group of young Marines, having recently graduated from Officers Candidate School, arrived at New River, North Carolina, a sprawling tent city that stretched over a vast area and would eventually become known as Camp Lejeune.

Four second lieutenants—William H. Sager, Phillip Wilheit, Herman Abady, and Joseph Anthony Terzi—were assigned to the 1st Marine Division, 1st Marine Regiment, 3rd Battalion, K Company, commanded by Captain Robert Putnam. It was a unit that was just forming.

Putnam was respected as a hard but competent officer. Some of his men, such as Pfc. Don Bishop, would later describe him as having a slightly “holier than thou” attitude.

Lieutenants Sager, Wilheit, and Abady were assigned to take command of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Rifle Platoons, respectively. Joe Terzi, an All-American football player from Long Island, New York, was given command of K Company’s light weapons platoon, which consisted of .30-caliber light machine guns and 60mm mortar squads.

“It Was Freedom vs. Fascism”

The commander of the 3rd Battalion, of which K Company was an organic unit, was Lt. Col. Bill “Spike” McKelvy, a colorful yet enigmatic character who came from a long line of Naval Academy graduates. The battalion roster also included two additional rifle companies: L and I, as well as M Company, a heavy weapons unit that was equipped with the Browning water-cooled .30-caliber machine gun and 81mm mortars.

America and her soldiers saw the war framed in basic terms. To borrow a title from American filmmaker Aaron Russo, “It was Freedom vs. Fascism.” It was obvious to everyone that the alliance between Germany’s Adolf Hitler, Italy’s Benito Mussolini, and Japan’s Emperor Hirohito was on a brazen march to force the world into a totalitarian order, placing all free men in the service of a brutal oligarchy.

If they bothered to keep up with world affairs as reported in the newspapers, magazines, and radio bulletins of the day, the youth of America were likely aware of the Japanese invasions of China, Manchuria, and Korea, beginning in the early 1930s. For some young Americans, it was the reports and rumors of Japanese brutality that inspired them to join the Marines and motivated them to fight.

Such global hot spots may have inspired others to sign up, but certainly the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor brought the matter closer to home. The situation at hand revealed that the die had been cast, the battle lines had been drawn, and a war of survival had to be fought.

Most of the K Company officers and enlisted men (the latter of whom had received their basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, arriving at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in February) came from the small towns and farms of America. Without knowing the definition of fear, they signed up the day after Pearl Harbor and were anxious to get into the war on the ground floor.

“You Ain’t Nothing But a Deacon”

Lieutenant Sager remembers that his men thought war could not possibly be worse than the harsh training regimen they endured. Pfc. Don Bishop recalls having to march all day in the hot North Carolina sun wearing several layers of clothing as the drill instructors sought to cull the weak from the strong.

Returning from an all-day march drenched in sweat, Bishop pushed his cap back on his head in an attempt to get some relief from the scorching heat. The drill instructor tersely approached him and jerked his cap back down. Bishop, exhausted, nervous, and at port arms, jumped back, his rifle with fixed bayonet almost stabbing the drill instructor.

“Watch it there! You almost stabbed me! What’s your name, Marine?” the drill instructor snapped.

“Private First Class Don Bishop, sir!”

“Listen to me, Bishop—from now on you ain’t nothing but a Deacon!” (In the Roman Catholic Church, a deacon is of a lower rank than a bishop, so the drill instructor was “demoting” the private first class; “Deacon” became Bishop’s nickname thereafter.)

As time went on, officers and enlisted men grew tighter and more familiar through the harsh training. The motto was “hang loose,” and training relied primarily on noncommissioned officers to maintain control and discipline of the men.

Amphibious landing maneuvers were carried out the week of May 17, 1942. The official history of the 3rd Battalion records: “The period from 16 February 1942 to date of departure [21 June 1942] from Marine Barracks, New River, N.C., was spent by this battalion in organizing, equipping and intensive training.

“Training consisted of basic training, marksmanship firing, musketry problems, bivouacking from one to two weeks at a time, night problems, landing exercises using cargo nets slung over the side of a transport built on the bank of the ‘Inland Waterway,’ and landings made on the beach from the ocean side.”

Deemed almost sufficiently trained for its first exposure to combat, the 1st Marine Division, after traveling via train to San Francisco, boarded the transport USS John Ericsson, which carried them to Camp Paekakariki outside Wellington, New Zealand.

Landing on Guadalcanal

Upon arriving in Wellington in July, the Marines were scheduled for another six months of training, but those plans were quickly cancelled. It was there that the Marines learned they would take part in the first land offensive against the Japanese on the island of Guadalcanal. An airfield there was 90 percent complete, and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C., did not want the Japanese to finish it.

The official history said, “They feared that the establishment of such a base might presage a thrust southeastward that would sever the line of communications between the United States and Australia, and plans were quickly changed to focus the counteroffensive on the seizure of Guadalcanal and Tulagi.”

The first three major land engagements on Guadalcanal—the Battles of the Tenaru (actually the Ilu) River (August 21), Bloody Ridge and Overland Trail (September 12-16), and Matanikau River (October 1942)—would all involve the same objective of trail or road access to Lunga Airfield, the island’s airstrip.

The division departed Wellington and steamed to the Solomon Islands for Operation Watchtower. At 4:30 am on August 7, 1942, the Marines were awakened on board ship, and a hot steak and eggs breakfast was offered to those who had the stomach for it. A fierce naval bombardment commenced, hitting Guadalcanal and the smaller nearby island of Tulagi, as well as two small islets, Gavutu and Tanambogo.

The Marines’ landings that morning caught the enemy by surprise and with a small force; only after their airfield was complete did the Japanese plan to bring in large numbers of crack troops to Guadalcanal.

The invasion force was split into two groups. The 1st and 5th Marine Regiments came ashore at Red Beach at 8:30 am. McKelvy’s 3rd Battalion, which included the four second lieutenants of K Company, was in the third wave to hit the beach.

Colonel Merritt Edson and his Raider Parachute Battalions, with the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment, faced suicidal resistance on Tulagi and its two islets, a foreshadowing of the fierce fighting to come on Guadalcanal. But the Tulagi islet areas were secured by the second day.

After hitting the beach at Guadalcanal on August 7, the Marines of K Company, along with the rest of the 3rd Battalion, were ordered to seize a terrain feature known as the Grassy Knoll (aka Mt. Austen). At an elevation of 1,000 feet, it overlooked the airfield and part of Guadalcanal’s coast and was therefore an ideal tactical acquisition. The Marines soon found out it was three miles inland, rather than just one mile as their maps indicated.

The Marines, however, did manage to capture the Lunga Airstrip, along with its warehouses and construction equipment that was quickly deployed to finish building the airfield. After taking the airstrip, the Marines promptly renamed it Henderson Field in honor of Major Loftus Henderson, a Marine Corps aviator killed in the Battle of Midway.

The warehouses contained Japanese food—canned crab, fish heads, and rice—that had been contaminated by worms. Third Battalion Doctor Ben Keyserling passed by the chow line, administering the malarial depressant Atabrine and advising the Marines not to pick the worms out of their rice. “It’s going to be the only protein you get, so leave them in there,” he said.

Also captured were large amounts of Japanese whisky and saké. Lt. Col. McKelvy immediately ordered the liquor off limits to everyone except (no surprise) himself. His men remember him being a bit tipsy at times.

Disaster at the Battle of Savo Island

While the Marines were tramping inland trying to reach Mt. Austen, British Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley, on loan to the Royal Australian Navy, was patrolling the waters around Guadalcanal with his ships of Task Force 62.2 divided into three groups located north, south, and east of the island. The formidable task force was composed of three Australian and five U.S. cruisers, 15 destroyers, and a group of minesweepers, but Crutchley was in for a nasty surprise.

It started on August 8, when U.S. Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher withdrew the aircraft carriers that had been providing air cover for the Marines on Guadalcanal. That night, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa of the Imperial Japanese Navy took advantage of the situation and brought his seven cruisers and one destroyer down “the Slot” between Guadalcanal and Savo Island.

Having sent out seaplanes earlier in the day, by nightfall Mikawa now knew the location of U.S. and Australian ships. In the dark, Mikawa first came across the cruiser Chicago, which, in the exchange of fire, was badly damaged but managed to limp away to safety. However, the crew of Chicago inexplicably neglected to notify other ships that a Japanese attack was underway.

Continuing on, Mikawa then located and sank Crutchley’s flagship, the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra, as well as the U.S. cruisers Vincennes, Quincy, and Astoria. More than 1,100 sailors were killed and 700 wounded in the Battle of Savo Island, one of the U.S. Navy’s worst defeats. The Navy and Marines subsequently referred to the waters around Guadalcanal as “Iron Bottom Sound.”

After the resounding defeat, Fletcher elected to withdraw all U.S. naval forces from the area, taking with him 50 percent of the 1st Marine Division’s scheduled equipment and supplies. Returning on August 9 from its unsuccessful assignment to capture Mt. Austen, McKelvy’s 3rd Battalion was shocked to find the beaches empty. The men had expected to see the Navy guarding the area and continuing to offload supplies. But there was nothing.

A Line Only One Man Deep

Although caught off guard by the Marine landing, the Japanese quickly collected units that were spread across Asia and rushed them to Guadalcanal. On August 18, Regimental Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki landed with an initial contingent of 920 men (out of 2,300) with plans to take back the airfield. But on August 21 Ichiki’s men ran into the Marines that were about a mile east of Henderson Field and were chopped to pieces in what has become known as the Battle of the Tenaru River (also known as the Battle of the Ilu River and the Battle of Alligator Creek).

When the second element of the Japanese regiment landed at Taivu Point, between August 29 and September 4, they discovered that Ichiki was dead and the first element had been almost entirely wiped out. Realizing its strategic importance, the Japanese continued to funnel troops to Guadalcanal.

On September 2, McKelvy’s 3rd Battalion took up a position on the eastern sector of the island that snaked through the jungle for 3,400 yards. At the extreme right flank of the battalion’s position, K Company guarded the Overland Trail, which led directly back to the much coveted Henderson Field, only a mile away.

Directly opposite K Company was a 750-yard-wide kunai grass field behind which lay dense jungle and the Tenaru (Ilu) River. K Company’s line ran the entire length of the kunai grass field with each rifle platoon guarding an area 250 yards wide. 2nd Lt. Herman Abady’s 3rd Platoon was split right down the center by the trail, with two rifle squads on either side. To the left of Abady was Wilheit’s 2nd Platoon, and on the right was Sager’s 1st Platoon.

Even in a hot battle zone, the strained relationship between the 3rd Battalion commander and his men became the focal point of numerous pranks. On one occasion a Marine walked outside McKelvy’s tent in a pair of Japanese split-toed moccasins, leaving a distinct set of footprints. Upon waking up that morning, McKelvy’s men held back their laughter as they heard him scream, “Jesus Wept! Jesus Wept! Those god-damned Japanese bastards were right outside of my tent!”

No more than several hundred yards from the airfield’s perimeter was the headquarters of Maj. Gen. Alexander Archer Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Infantry Division. If Japanese forces could seize the Overland Trail and retake the airfield, the Guadalcanal campaign would indeed take a perilous turn.

The 60mm mortar squads from 2nd Lt. Terzi’s weapons platoon were emplaced 200 yards behind the line, with the remaining machine-gun squads on either side of the trail entrance. M Company’s heavier 81mm mortar and Browning heavy machine-gun squads were also deployed to strengthen the K Company line.

Sager’s right flank was unprotected. A yawning, 300-yard gap extended up to Colonel Edson’s Raider Battalion that had recently been put on the ridges directly overlooking the airfield. Despite being worried about his exposed right flank, Sager knew nothing could be done about it. If the Japanese located this gap, they could walk back to the airfield without firing a single shot. With no reinforcements, the Marine line was only one man deep.

Fortunately, the enemy did not find the gap. However, more miseries were visited upon the Marines. The lack of adequate food and the abundance of malaria, jungle rot, and torrential rain took a heavy toll. Japanese naval guns and bombers from Rabaul on the island of New Britain constantly pounded Marine Corps positions.

The Diary of Noel Billy Guise

The diary kept by Pfc. Noel Billy Guise of K Company’s weapons platoon provides a glimpse of what the battle against the Japanese in September 1942 was like:

“September 2: While on outpost all hell broke loose. Shelled and bombed. Came back to camp—Then got word to move out. We are now in defensive position at edge of open field—Raider Bn. supposed to chase Japs into us. Got more mail. 18 bombers came over. Saw two planes crash in field.

September 4: Rained all night. God, it was terrible sleeping in the mud and puddles. Plenty of mosquitos. Have 30 or 40 bites on each arm. After breakfast 5 of us volunteered for a patrol. Went back to river where we spent 2nd night but saw no Japs. Came back hot, tired and thirsty.

September 6: Quiet night. Beautiful morning here on the front lines. Coconut grove on the left across the field, then jungles and then colorful mountains—purple, blue and the peaks hidden by clouds.

September 7: Paul and I went on guard at 4:00 am and was scared to death by a boar. Rained all night and mud is ankle deep. We’re still eating Jap food and it’s full of worms. We’re almost starved. Rained all day in buckets full. Our chow in the morning light was covered with water because there was no shelter to go to. We went to bed while it was still raining. We slept in a puddle of water if you want to call that a bed. It’s a miracle we’re not all dead.

September 8: It rained until three this morning. Everyone soaked. Built a fire to try to dry our clothes. Went on working party to make a road thru jungle. What a job. Rained about 10 and stopped at 4. Chow is getting less and less. Army at New Caledonia brought cigarettes and said they were for Marines at Guadalcanal. How nice. Guard at 10:30.

September 10: Everyone hungry. Worked on road in morning. Air raid 28 bombers. That was too close for comfort. Grass, weeds and branches fell all over us. George, Bower & Slok [sic] went after some food. We ate a little and it sure was good. I’m so damn weak I can hardly do anything. We finally had a good chow. Boy are we stuffed. Another air raid 26 bombers. Japs are coming down from the hills.

September 12: Quiet nite [sic]. God I hope they feed us today. Air raid 27 bombers and plenty of Zeros. What a sight—burning planes going down all over the sky. We got 17—rest ran into an aircraft carrier on the way back—10 bombers & 42 [Zeros] shot down.”

Marine Patrols on Guadalcanal

Marine Corps units were aggressive in their patrolling. After arriving at the eastern sector, 2nd Lt. Bill Sager took his platoon on a patrol several miles into Japanese territory. The jungle was practically impenetrable, and the Marines needed machetes to hack their way through the dense foliage. No enemy was encountered.

One week later the Marines returned to the same area but with very different results. They discovered evidence of large enemy troop movements and found quantities of discarded cartridge belts, ammunition containers, cigarette wrappers, empty fish cans, and Japanese split-toed moccasins.

Upon returning from this second patrol, Lieutenant Sager relayed the details to Captain Putnam, who put him on the phone directly with Colonel Gerald Thomas of division intelligence. Sager deduced that the Japanese were headed southwest, towards the ridges overlooking the airfield where the Raiders were dug in.

At this time General Vandegrift had the majority of his forces at the beach area in anticipation of a Japanese amphibious assault. The patrols led by Sager may have been significant factors that led Vandegrift to put Colonel Edson and his Raider Battalion on the ridges, backed up by the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment.

On September 11, Corporal Walter Wrazen led a five-man listening post from Lieutenant Sager’s 1st Platoon to the east of K Company’s position. At around midnight, contacting Putnam via sound-powered phone, Wrazen said they heard large Japanese troop movements in the jungle, so the listening post was immediately withdrawn. Upon returning, Sager and Putnam questioned Wrazen extensively but doubted that he heard anything.

The following day, September 12, Lieutenants Wilheit and Abady took a six-man patrol approximately seven miles inside Japanese territory but were unable to make any close-in identification of enemy forces. They did, however, sense that they had been under surveillance from a series of ridges above their route of march. Wilheit wanted to return using an alternate path that led up a hill, but Abady convinced him to return via the same route along a creek bed with only a minor deviation.

The next morning Captain Putnam held a critical meeting at his command post. Lieutenant Terzi asked if he could take a listening post out that night, vowing to blast the hell out of the Japanese if he found them. Putnam granted him permission. Later that night Terzi, armed with his Colt .45, along with Privates Stephen Jabo, Charles Laurence, Thomas Pilleri, Orland Mixter, and Leo “Mac” McDermott—all of whom carried Thompson submachine guns—set out across the 750-yard-wide kunai grass field and disappeared into the jungle.

The Kuma Battalion

But where were the Japanese? Also having been deployed to the area in early September, the Kuma (Bear) Battalion under the command of Major Eiji Mizuno had been given aerial reconnaissance photos showing that the trail led directly back to Henderson Field.

After their staggering defeat on August 21 at the Battle of the Tenaru River, the Japanese had developed a three-pronged strategy for taking back the airfield. The main attack would be led by Maj. Gen. Kiyotake Kawaguchi at the center ridges overlooking the airstrip while Colonel Akinosuke Oka would attack from the west. From the east the Kuma Battalion would also push toward the airstrip. Though smaller in scope, the flank attacks were essential stress on the Marines’ line, which the Japanese felt would cause it to break.

The Kuma Battalion was an ad hoc force that included 130 men who had escaped annihilation at the Tenaru on August 21. The remaining elements had recently landed at Taivu Point from August 29 to September 4 and were composed of six elements, which included Mizuno’s command staff and a small engineering squad. Two infantry companies were led by 2nd Lieutenants Kiyoshi Satou and Toshio Habara; Satou’s company had 177 men while Habara’s had 169.

Satou’s company also had three Nambu 6.5mm light machine guns, while Warrant Officer Kosaku Nakao had one oversized Nambu 7.7mm machine-gun platoon consisting of four squads with 17 men in each, for a total of 68 men. 1st Lt. Yoshio Ohkubo commanded a 37mm (Type 94) gun company of 80 men, which brought the total strength of the Kuma Battalion to 550.

The climate and terrain of Guadalcanal were unforgiving and played no favorites. Mizuno and his men had been hacking their way through the jungle for nearly two weeks and were thoroughly exhausted. On the evening of September 12, the men of the Kuma Battalion heard tremendous gunfire breaking out to their west, which they correctly assumed was General Kawaguchi making the main attack at the ridges overlooking the airstrip.

At this point Mizuno was 1.5 kilometers south and one kilometer east of where he needed to be. In the early morning of September 13, he shifted his force in a northwesterly direction. Later that afternoon he sent his adjutant, 2nd Lt. Nobuo Fuji, on a reconnaissance mission with several other soldiers to locate the K Company line.

Shortly after sunset, Fuji reported to Mizuno that he had spotted what appeared to have been a machine-gun emplacement behind a line of barbed wire across the grassy plain in front of his observation point. Fuji said, “If the Kuma Battalion could attack and penetrate this position, it could surely reach the airstrip without much difficulty.”

Later that night Mizuno decided to lead the attack with his headquarters and the engineering squad followed by the infantry units. The machine-gun platoon and 37mm gun company would be positioned on the western bank of the Tenaru to offer supporting fire but would not participate in the initial thrust at the Marines’ positions.

In single file, the Kuma Battalion silently crept into the jungle. The wind blew through the trees, and the sound of unknown jungle life could be heard in the distance. General Vandegrift had recently elected to relocate his HQ and command staff about 300 yards from the airfield’s perimeter. If Japanese forces managed to seize the Overland Trail, America’s Guadalcanal campaign might indeed have taken a dramatic turn for the worse.

Marine turned author William Manchester noted, “Enemy breakthroughs seemed imminent. One night a Japanese officer brandishing a samurai sword came within a few yards of the pagoda-like structure that served as Vandegrift’s command post. The general, pacing the muddy, wooden floor, turned, startled. ‘Banzai!’ screamed the Jap, disemboweling a gunny.” The intruder was killed by a shot from an alert sergeant’s pistol.

Mizuno, his command staff, engineering squad, and elements of the 1st Company, soaked, muddy, and sporting welts from ferocious mosquito attacks, soon reached the east bank of the Tenaru River. But where was the whole 2nd Company? Contrary to his own instructions to attack as a unified force, Mizuno impatiently decided to launch the attack. The Japanese force waded across the Tenaru, crawling up its western bank and pausing momentarily before proceeding toward the kunai grass field.

Bayonet Charge on the Overland Trail

Simultaneously, Terzi’s Marine listening post continued making its way into the darkness carrying a field telephone line that reached back to a sound-powered phone at the K Company CP. If Terzi’s men encountered the Japanese, they were to alert Captain Putnam and withdraw back to the Marine line before it was hit.

Suddenly, Private Leo McDermott heard a clanking noise that gradually got louder. He crouched down on one knee, his Thompson clutched tightly in his hands. Other members of the patrol did the same.

Terzi ordered the patrol to open fire. Bolts of light shot forth from their guns as they blasted away, killing some 20 of the Japanese. Major Mizuno ordered his men to hurl grenades at the Marines and a salvo of 20 to 30 blasts rocked the earth. What were the Marines doing here? No contact was expected until the Japanese reached the Marine line in silence.

Believing he had now hit the principal Marine line, Mizuno yelled at his men to fix bayonets and attack. His decision was upsetting and confusing for his men, but more importantly it diverted them from the main objective. In the chaos of the night fighting, Terzi told his men to scatter and quickly gave his Colt .45 to one of his men whose rifle had jammed. In the melee, Private Thomas Pilleri was killed.

As the firing intensified, McDermott and Terzi jumped into the Tenaru River and hid beneath an overhanging patch of earth. The Japanese ran up and down the western bank of the river, screaming curses into the night and firing wildly at any Marines they could see in the fractional seconds of light provided by the blasts from the grenades.

Back at the K Company line, Captain Putnam’s Marines heard the explosions and knew the Japanese were on their way. Putnam ordered Privates Hugh Harwood and Walter “Ski” Szalanski to open up with their .30-caliber Browning machine guns that were on either side of the entrance to the Overland Trail. Both guns fired about 1,000 rounds before Putnam gave the order to cease fire; he wanted to see what the Japanese response would be, but there was none. A tense period of silence followed.

At five minutes after midnight, K Company heard empty shell casings inside ration cans strung along the wire starting to rattle. It was the sound of Sergeant Masakichi Wada’s engineering squad cutting through the barbed wire. Putnam ordered his executive officer, Lieutenant Mike Scelsi, to launch flares. In the eerie cast of the light, the Marines could see the heavily camouflaged Japanese running across the kunai grass field.

Putnam yelled the order to commence firing, and Lieutenants Sager, Wilheit, and Abady echoed the command. Both sides opened up, their arsenals of weaponry unleashing an earsplitting series of explosions. The fighting raged through the night as both sides fought desperately for control of the lifeline, the Overland Trail.

The Kuma Battalion was closer than it had ever been to the airfield and Vandegrift’s headquarters, but such key tactical objectives would not remain within reach for long. Machine gunners Harwood and Szalanski cut bright lines across the field with their tracer ammunition. At one point a Japanese gun had a fix on Harwood’s position, but after several minutes Harwood won out.

At times the firing seemed to die down for significant periods only to be ripped away by more Japanese savagely engaging the Marines in hand-to-hand and bayonet fighting. Given the circumstance of close quarter combat, Captain Putnam decided to move one of the 60mm mortars to drop rounds just 30 yards beyond the Marine line. The mortar squad fired with its tubes pointed practically straight up in the air.

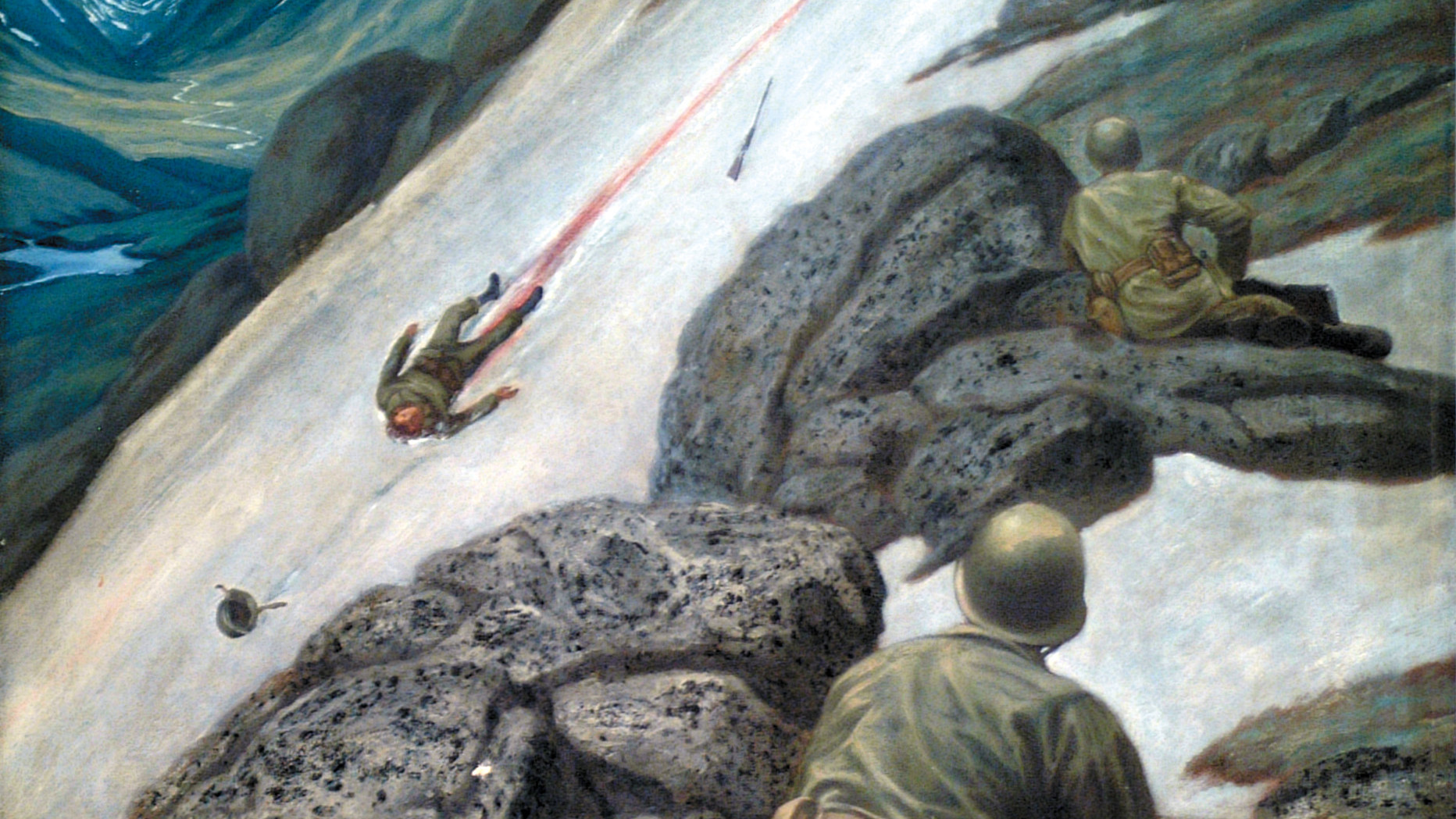

The Japanese assault began to fall apart. A bullet pierced Major Mizuno’s helmet, killing him instantly, and 2nd Lt. Nobuo Fuji, who had located the K Company line, was also killed. Refusing to be captured, Warrant Officer Shigekichi Katou took his own life with his pistol, while 1st Lt. Yoshiaki Sakakibara fled the scene. What was left of Mizuno’s command staff began to scatter.

A Second Charge

An eerie silence descended before dawn, and a pall of smoke covered the battlefield. Private Hugh Harwood peered into the dark distance. He sensed the Japanese might launch another bayonet attack and told his number two man on the gun, Private Jack LaBerge, to get the grenades ready. The plan was for LaBerge to throw the grenades while Harwood would free-swing the gun, scything down everything in its path.

As the sweat poured from his forehead in the stifling predawn heat, Harwood thought his eyes were deceiving him. Ever so faintly he could make out the Japanese coming across the field yet again. Despite being abandoned by their command staff, they somehow found the strength to press the attack. The blast of weapons resumed as the Japanese made one charge after another with fixed bayonets. Lieutenant Abady almost shot his own runner, Private Joe Flood, who was returning to deliver a message from Captain Putnam.

Suddenly a Japanese officer (probably Lieutenant Satou), with samurai sword in hand, broke through the line and yelled in good English, “Cease fire! Cease fire!” But Private Marion Peregrine took him out with a deadly burst from his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

A Japanese spotter began directing knee-mortar fire toward 3rd Platoon squad leader Corporal Haynie Bryant. A group of shells ringed his foxhole, with the last one landing only three feet away; luckily, his foxhole provided just enough cover to deflect the blast over his head.

Private First Class Don Gohl began lobbing grenades along with the Marines around him as the Japanese came through the wire. Gohl looked to his right and noticed that Private Harold Enias had been wounded by a chunk of mortar shrapnel.

From behind a banyan tree Lieutenant. Abady shot several Japanese with his Colt 45. Corporal Cloyd Hines blasted out rounds from his BAR and bayoneted a Japanese soldier, then collapsed himself, wounded in the temple by a grenade fragment.

A group of men from 2nd Lt. Toshio Habara’s company now located Sager’s 1st Platoon at the extreme right flank of the K Company position and sent mortar and machine-gun fire raining down on the Marines. Sager screamed at his men to open fire. Howard Hayes fired his BAR so fast and long the barrel overheated and warped, causing the rifle to jam. But Habara’s men were unable to break through. It was a close call, but the Marines held the line.

Assessing the Outcome of the Battle

As dawn lightened the sky, the men of K Company crawled out of their foxholes. Their eyes bloodshot, they stood motionless and dazed from the hell they had endured. The Marines dragged the mounds of dead Japanese bodies away from their foxholes to establish clear fields of fire.

K Company had fought valiantly, and the 3rd Platoon commanded by Lieutenant Abady bore the brunt of the assault. At daybreak, some 30 enemy soldiers lay at 3rd Platoon’s defensive positions with another 30 entangled in the barbed wire in front of them. The airfield and General Vandegrift’s command post remained just beyond the Japanese grasp.

Captain Putnam ordered squads to assess the area to its front. Private Don “Deacon” Bishop counted an additional 200 to 300 dead Japanese along the 3rd Battalion line. He also discovered the lifeless bodies of Privates Bertram Hanscom and Harold Enias, both from Abady’s platoon. Now blooded for the first time, K Company’s losses of three dead and 17 wounded were few but painful.

Over the next few days, members of the Terzi patrol made their way back to the 3rd Battalion line. Through the long nights, they had had to avoid the Japanese as well as their own artillery and mortar fire. Terzi would receive the Silver Star.

On December 15, 1942, the Marines of K Company heard the words they had yearned to hear for so long: “Men, prepare to leave the island; we’re headed for Australia.” They had spent four months, two weeks, and a day on what would come to be known as the “Island of Death.” The Japanese would refer to Guadalcanal as Jigoku No Shima, “Hell’s Island.” The period from August 7 to early November 1942 included some of the most tactically important land combat in the Pacific—and left 4,123 Marines dead. With grudging admiration, Vandegrift wrote to the commandant of the Marine Corps, “General, I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting. These people refuse to surrender.”

In addition to the forces commanded by Colonel Merritt Edson, the 1st Marine Regiment commanded by Colonel Clifton B. Cates, which included McKelvy’s 3rd Battalion, was responsible for the majority of fighting during this period. Guadalcanal was by no means the bloodiest fight in the Pacific, but it was the first land battle, and the American victory would guide and inspire troops and commanding officers of the Marine Corps as they fought their way to the doorstep of Japan.

After reaching Australia, the Marines of the 1st Regiment were billeted at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds. They did range work with their new semiautomatic M-1 Garand rifles, which were a vast improvement over the old, bolt-action Springfield 1903s they had used on Guadalcanal.

Abady and Sager, who had severe cases of malaria, returned to America in a casualty company; upon being released from the hospital, both were promoted to the rank of captain. Sager would receive an assignment to serve in SACO, the Sino American Cooperation Organization. He subsequently was sent to Kweichong Province, Camp Ten, where he trained Chinese guerrillas to fight the Japanese. Abady would receive orders to train Marines in amphibious warfare in America. Back in the Pacific, the surviving members of K Company would carry on the fight.

The Loss of Two Captains

Nearly a year later, on December 26, 1943, the Marines waded ashore at Cape Gloucester on New Britain. Joe Terzi and Phil Wilheit, both having been promoted to the rank of captain, led K Company troops. There was no beach area at the cape, so as the large doors of the landing craft swung open, they walked right into the jungle where, after a short distance, they turned right, went over a small brook, and then made a left. There they ran into a Japanese pillbox and began taking heavy automatic weapons fire.

Terzi was killed first. Wilheit assumed control of K Company but was killed moments later; rifleman “Deacon” Bishop of K Company’s 3rd Platoon pulled their bodies off the front line. The deaths were a tremendous blow to the morale of K Company.

Both captains were posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. The citation for Terzi reads: “The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Captain Joseph Anthony Terzi, United States Marine Corps Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service while serving as Commanding Officer of K Company, Third Battalion, First Marines, 1st Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Cape Gloucester, New Britain Island, on 26 December 1943.

“Realizing that the nature of the terrain made a powerful frontal assault necessary when his right assault company was stopped by concentrated enemy rifle and machine-gun fire, Captain Terzi notified his battalion commanding officer of the situation, then boldly led his men in a savage frontal attack, fighting valiantly until he was killed by Japanese fire.

“By his able strategy and determined aggressiveness, Captain Terzi inspired his men to carry through the assault with so much splendid and heroic effort that all enemy resistance was completely destroyed. His forceful initiative, steady courage in a time of great peril, and his unwavering devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Writing to Phil Wilheit’s widow, K Company’s newly appointed commander, Captain George P. Hunt, stated, “Bold, aggressive, fearless, he died as is expected of a Marine officer, at the head of his troops; and a vigorous inspiration to all, so calm and cool was his demeanor. He was struck by Japanese machine gun fire and was killed instantly.

“The impetus of his leadership and that of Joe Terzi, his company commander who was also killed at approximately the same time as Phil, was responsible for the ensuing victory that day and another one two days later. Their firm and driving spirits guided the company to glory against the enemy and still do.”

Company K Takes the Point at Peleliu

By September 15, 1944, the Japanese had spent 18 months constructing and reinforcing defensive positions on Peleliu. A deadly assortment of machine guns, mortar squads, and artillery awaited the Marines. Pillboxes were covered with up to six feet of cement and crushed coral. Many fortifications were surrounded by spider holes that had been blasted into the coral to hold snipers who could protect Japanese infantry. Jagged ridges overlooking the beach had also been cut out to hold additional pillbox emplacements.

The Japanese high command was shocked at the defeat on Guadalcanal, and victory at Cape Gloucester gave the Marines additional momentum. As the battle for Peleliu—codenamed Operation Stalemate II—approached in the fall of 1944, the outcome of the war was no longer an issue. America was on its way to victory, with one question remaining: How long would it take? The Japanese knew that victory was little more than a dream. With each passing day it slipped farther into the fog of a distant memory, but the Japanese vowed to bleed the Marines white with every ounce of strength they had left.

The Marines felt supremely confident in their ability as a fighting unit. Colonel Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller had gained significant respect for K Company. For this reason he gave Captain George P. Hunt and the Marines of K Company the task of clearing The Point on White Beach at Peleliu.

Rising some 30 feet above the water’s edge, The Point overlooked all 600 yards of White Beach. It was of the highest necessity that it be seized immediately, as not having control of it would expose the entire 1st Regiment to heavily concentrated enemy fire.

Hunt thoroughly rehearsed his men for the upcoming battle. Each Marine in K Company knew his task and its significance to his squad, and each man understood the gravity of the orders given to them by Colonel Puller and stood ready to fulfill them.

Captain Hunt decided to anchor his left flank on the beach, while another force would pivot 90 degrees. The 3rd and 1st Platoons were given the job of clearing The Point while the 2nd Platoon was to secure the area to the right.

On the morning of September 15, 1944, the landing craft approached the island and ground to a halt; Hunt ordered his men over the side and off the beach as quickly as possible. Running 75 yards straight ahead, he took cover in a blast hole, but the Japanese pillboxes and jagged coral quickly took a deadly toll. Most of K Company’s machine-gun squads were mowed down as soon as they hit the beach. Hunt’s command group had taken cover around him, and orders were given for the radio operator to make contact with the platoons—but to no avail. Runners were sent out to gain information but none returned.

Desperate to gain a handle on the situation, Hunt jumped from cover and screamed at his radio operator to follow him. He was devastated by the horror that confronted him. Dozens of his men lay dead or wounded, their faces grimacing in pain. In just a few minutes, one of the finest companies in the 1st Marine Division had been decimated.

Sergeant John Koval assumed command of the 3rd Platoon after its officer was badly wounded and taken out of the fight. This was the unit commanded by 2nd Lt. Abady on Guadalcanal. Despite being close to death himself, Koval rallied what remained of 3rd Platoon to The Point, where he was responsible in large part for knocking out a major Japanese gun emplacement. For his courageous actions, he was awarded the Silver Star. Pfc. Joe Dariano recalls that of the 45 Marines in his platoon, 19 were killed and 21 wounded—a casualty rate of 89 percent.

while they were still on the beach. The Marines of Company K absorbed heavy casualties while attempting to clear The Point, an objectiveoverlooking the landing area on White Beach.

As nightfall approached, the Marines piled up stones to provide cover. Hunt called for flares to be sent up, illuminating the battlefield in a starburst of light. It was a situation reminiscent of flares being sent up before K Company’s battle at the Overland Trail. Then someone screamed, “Here they come!” A BAR opened up, followed by grenades exploding in close succession. The fight raged through the night. K Company miraculously took The Point—but at tremendous cost.

On D+1, reinforcements and supplies were received throughout the day. They were just in time, as Hunt estimated over 80 percent of his men were either dead or wounded. By D+8, K Company was pulled off the front line with what remained of the 1st Marine Regiment. By the time reinforcements arrived, K Company had suffered 157 casualties and had only 18 men left who could carry a weapon. For his superb leadership, the Navy Cross was awarded to Captain Hunt, who went on to become an artist and managing editor of Life magazine after the war.

Remembering the Sacrifices of Company K

Historians have often asked whether it was necessary to take Peleliu. General Douglas MacArthur stated he wanted the Marines to seize Peleliu so he could have them on his flank as he retook the Philippines. Tragically, the Marines were never called upon to support MacArthur from Peleliu.

Peter Richmond, author of the book My Father’s War, interviewed retired Brig. Gen. Gordon Gayle who commanded the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, on Peleliu and received the Navy Cross for getting his men across the island’s airfield first. When Richmond asked him how he felt about Peleliu, Gayle responded, “I feel terrible about it. This is the one thing that’s been hard for me to come to grips with: the fact that I lost 60 percent of my officers and 50 percent of my men to a campaign that did not need to be fought.”

From the jungles of Guadalcanal to the deaths of Terzi and Wilheit at Cape Gloucester through the bloodstained coral at Peleliu, K Company fought in the highest tradition of the Old Breed. These men were emblematic of many Marine Corps detachments that fought in the Pacific. Their actions will forever be remembered in the annals of the Marine Corps.

My dad Francis Robert (Bob) O’Brien was in K Company and fought at and survived all three island campaigns. He was severely wounded on Peleliu and honorably discharged from the Marine Corp at the end of 1944. He passed away here in Tucson, AZ in June of 2018 at the age of 95. He was prominently mentioned in Captain Hunt’s book “Coral Comes High”. God bless him and all the men of K Company. Semper Fidelus.

My dad Jerry Bittner was BAR Asst at this campaign in a rifle team that was reduced to three as Bill Darling was assigned stretcher duty. So it was Murray the team leader Huffman on BAR and dad. Dad exited the landing craft right behind Lt Woodyard the Lt took a hit and fell dead right in front of dad. 2nd pla found themselves in a tank trap which became a death trap. Dad after peering out of the trap had a shot enter the front and exit the side of his helmut. The platoon was pinned down all day. Sometime around 5PM dad Huffman and two others exited the trap and found their way to Capt Hunt CP…they spent the first night in hand to hand combat. Braswell Deen a new man to the platoon somehow was out in front of the trap, alone most of the day around 6PM a sherman tank came up to the trap and 9 survivors of the days battle followed it under cover back to the beach. Joe Dariano stated the platoon had 19 KIA 21 WIA 1MIA I believe the platoon would have been about 45 marines and corpsman. A 17 year old from Ma is still listed as MIA PFC Edward Fred Borowski.

My Dad was also at Guadalcanal as a Sgt then New Britain

Much to tell.

Daniel O’Brien,

My Grandfather, Eugene Hansen, was also on and survived all three islands as well! He is mentioned at the beginning of “Coral Comes High” when they are on the boat playing a game of hearts and taking all of their nickels! Also mentioned a couple of other times throughout the book.

where are we going to find men like this in our new liberal society?

I was the last member of the Vietnam era 173d Abn when I retired

Kinda scary ain’t it.

will not find men of that caliber who fought then. pampered pups now. there will be a few that could handle it, but very few. it also depends on WHY they would be asked to fight.