By Robert F. Dorr

Lieutenant William A. “Bill” Klenk, piloting a Curtiss SB2C-3 Helldiver, bristled at the “clawing, miserable weather,” with inverted pyramids of cloud hanging from a low ceiling and gray murk everywhere. Down below him, the Japanese destroyer Hatakaze was maneuvering at high speed in the South China Sea. It was January 15, 1945.

Klenk observed the elusiveness of the fast-moving destroyer: “A thin, narrow target that would have been hard to hit even if he wasn’t jinking from one direction to another,” Klenk said in an interview for this article.

Accompanying Klenk were four other deep-blue, cylinder-shaped Helldivers, each with a pilot and radioman-gunner aboard, jockeying into position to attack the destroyer. They belonged to Bombing Eighty, or Squadron VB-80, from the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga (CV 14). There were supposed to be six, but one squadron pilot had aborted with mechanical trouble.

Klenk was, by this point in the war, a seasoned pilot of the Helldiver. He believed the SB2C had overcome early technical troubles and achieved its design goal of being faster and more robust than the SBD Dauntless of Battle of Midway fame. “It was not the most forgiving aircraft,” said Klenk. “You had to learn it. But once you’d ‘gotten’ it, the Helldiver would serve you well.” Klenk added, however, “Still, some of the guys never stopped calling it ‘The Beast.’”

“Son of a Bitch Second Class”

The Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics ordered the SB2C on May 15, 1939, at a time when its fabric-covered, biplane predecessor, the SBC, also called the Helldiver, was still standard equipment in its carrier air groups. The new SB2C was a tailwheel-equipped, low-wing monoplane similar in appearance to the Brewster SB2A Buccaneer, against which it competed successfully. Ironically, Brewster may have been the only aircraft manufacturer with more factory-floor workmanship and corporate management problems than Curtiss.

Apart from having an internal bomb bay not found on the Dauntless, the SB2C was unremarkable in appearance: It had 49-foot, 9-inch wings that folded for carrier stowage, another feature not found on the Dauntless. The pilot and radioman-gunner sat in tandem, the latter with a seat that could rotate to face in any direction.

The Helldiver derived its power from a 1,900-horsepower Wright R-2600-20 Double Cyclone, 14-cylinder, two-row radial piston engine driving a 12-foot, four-bladed Curtiss Electric propeller. The powerplant experienced some early developmental problems but these were resolved more quickly than were the aerodynamic and structural problems associated with the Helldiver.

The head of the SB2C Helldiver engineering team was not Curtiss’s well-known Don R. Berlin (who created the P-40 Warhawk) but the company’s Raymond C. Blaylock. The prototype XSB2C-1 made its maiden flight on December 18, 1940, but crashed days later; Curtiss rebuilt the prototype. It flew again and crashed again on December 21, 1941, when test pilot Barton T. “Red” Hulse had to bail out during a high-speed dive. Small wonder critics were beginning to suggest that SB2C stood for “son of a bitch second class.” Apart from the familiar “Beast” appellation, some pilots were calling the aircraft the “Clunk.”

“I’m Your Average Naval Aviator”

Nor was a lot of comfort to be gotten from the maiden flight of the first production SB2C-1 on June 30, 1942. A shift of production from Buffalo to a new plant in Columbus, Ohio, led to quality-control issues on the assembly shop floor and criticism from the Senate committee on national defense headed by Senator Harry S. Truman (D-Mo).

Klenk, who picked up an early-model SB2C-1C at Columbus, said it was “common knowledge” that the work practices at the plant were shoddy. By publicizing these issues, the Truman Committee helped to bring about improvements.

“On that early version the bad reputation was deserved,” said Klenk. “The arrangement in the SB2C-1C cockpit was horrible. It was a hydraulic nightmare. There were six hydraulic valves in the cockpit and we had to memorize all the combinations for emergencies. If the flaps wouldn’t come down, you had to turn a couple on and off. If the wheels didn’t come down, you needed to remember a different combination of ‘on’ and ‘off.’

“To improve the cockpit in the SB2C-3 model, they eliminated valves and simplified their use, put in different emergency procedures. It still had a lot of problems. One problem: to get the landing gear up, you had to reach pretty far forward to get the landing gear handle. If your shoulder straps were pulled tight, you could not reach it. They eventually put an extension on the handle so we could reach it.”

Mostly because of poor stability and structural flaws—both later remedied—Britain rejected the Helldiver after taking delivery of just 26. The U.S. Army curtailed plans to put its A-25 Shrike version into combat; the Army’s 900 Helldivers ended up doing utility work. Some were transferred to the Marine Corps to become trainers and given the out-of-sequence designation SB2C-1A.

The January 15 air strike was big. Two hundred Navy warplanes from two full carrier air groups—from Ticonderoga and USS Essex (CV 9)—struck Japanese naval forces along the Formosa coast. The bad weather, the heavy antiaircraft fire, and the elusiveness of Japanese warships reminded Klenk of an earlier mission.

Weeks before, on November 5, 1943, Klenk and his squadron mates in VB-80 attacked the Imperial Japanese Navy at Manila Bay. On that mission, the Helldivers sank a destroyer after Klenk put a bomb squarely down the ship’s stack. For that, Klenk received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

“I’m your average naval aviator,” said Klenk. “We were products of very good training. It was not uncommon for the Navy to take a year to 18 months to transform a new student pilot into a seasoned flier ready for action in the Fleet. It was a luxury the United States could afford. As far as I know, we never sent any aviator into battle who wasn’t fully prepared.”

From Civilian to Combat Pilot

For Pennsylvania native Klenk, the war began at a football game in Washington’s Griffith Stadium when his beloved Philadelphia Eagles were playing the Washington Redskins before 27,102 fans on December 7, 1941. Suddenly, the announcer was calling out names of important people in the nation’s capital and telling them to report to work.

But Redskins president George Preston Marshall would not allow an announcement of Japan’s attack on the U.S. Fleet during the game, explaining that it would distract fans. That made Griffith Stadium one of the last outposts of an era that had already slipped away. After Philadelphia won 20-14, Klenk and a friend learned about Pearl Harbor from an “extra” edition of the Washington Star newspaper.

Bill Klenk’s journey from civilian to naval aviator took more than two years. The United States could afford to spend that long training a pilot, and could keep huge numbers of men in the training pipeline so that those who had experienced war could return home after a period of time. Neither lengthy training nor any end-of-tour relief were luxuries the Axis nations could afford. A typical U.S. naval aviator in a carrier-based squadron was expected to complete two combat cruises. Many, like Klenk, got into the war too late to ever begin a second cruise.

Klenk’s first trip to the recruiter led to a rejection. “I was a skinny kid, five feet ten, weighing just 100 pounds. I was told to go home, eat some bananas, and come back again. I was earmarked for pilot training and sworn in as a Seaman 2nd Class in the U.S. Naval Reserve on May 26, 1942.”

Neither Nazi Germany nor Imperial Japan could afford to shunt around a pilot trainee the way the United States routinely did. Klenk underwent ground training and then went to Hutchinson, Kansas, for primary flight instruction in the Stearman N2S biplane. He made his first flight in the Navy on December 10, 1942. He went to Corpus Christi, Texas, for basic flight training in the Vultee SNV-1, then transferred to Kingsville, Texas, for an introduction to dive bombing in the SBD Dauntless.

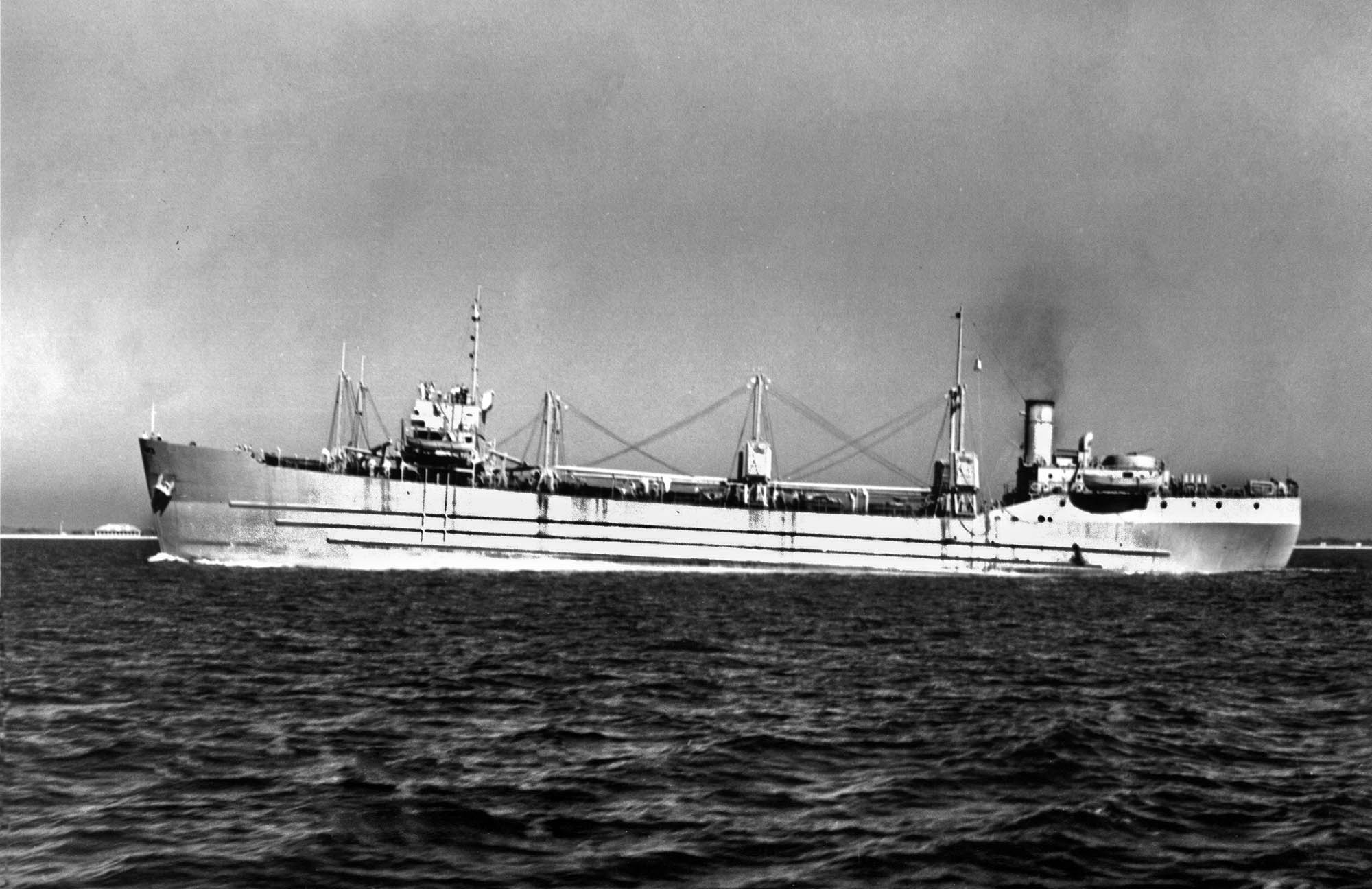

After all that, Klenk received his ensign’s commission and aviator’s wings of gold on May 7, 1943. He was then assigned to Jacksonville, Florida, for operational training in the SBD Dauntless and thereafter to Glenview, Illinois, for carrier-landing practice, landing the Dauntless on the carrier USS Sable (IX-81), a converted side-wheel steamer used for training on the Great Lakes. Only after that was Klenk assigned to Squadron VB-80, which formed at Wildwood, New Jersey, in February 1944. The squadron soon moved to Oceana, Virginia, to prepare to go aboard the Ticonderoga.

Improving the Helldiver

Meanwhile, Curtiss was improving the Helldiver design. Lengthening the fuselage by one foot and redesigning the fin fixed the plane’s most serious aerodynamic problem. Curtiss built 978 SB2C-1 models and a single XB2C-2 seaplane version before turning out 1,112 SB2C-3s with numerous minor changes to engine and propeller.

More than 15,000 U.S. pilots lost their lives while training for a war they never reached––and Klenk almost became one of them. “When we got our new SB2C-3s in Virginia, we did carrier qualifications,” he said. “On my first flight in the SB2C-3 model, I made normal approach to the USS Charger [CVE 30] in the Chesapeake Bay. Because of a manufacturing flaw, I had a bad tailhook.

“After my normal landing, the tailhook pulled out of the airplane and stayed on the wire while I kept going up the deck toward parked planes. My right wingtip hit the island and my plane spun around and then I hit the island head-on right under the bridge and almost knocked the captain overboard.” No one was seriously hurt.

The principal version of the Helldiver, and the one eventually operated by Klenk’s squadron, was the SB2C-4, of which 2,045 were built, with redesigned flaps for improved dive performance, a propeller spinner, and eight under-wing stations for 5-inch high velocity aircraft rockets. Curtiss built 970 SB2C-5 models with increased fuel capacity but these were too late to see combat. Total production was 7,141 Helldivers.

Attack on the Hatakaze

In the spring of 1944 with most of the Helldiver’s teething troubles behind, Klenk’s squadron went aboard the Ticonderoga and embarked for the Pacific. Ticonderoga’s air wing, including squadron VB-80, saw its first combat in the Philippines on November 5, 1944—21/2 years after Klenk was sworn in. By the time of his first combat, Klenk had 800 flight hours and 51 carrier landings in his logbook. “That was typical of me and of all of those around me,” he said.

Ahead was the January 15, 1945, action off Formosa.

“The Japanese were using high-speed destroyers as transports to move ships and supplies during the night,” Klenk said. “A destroyer is very narrow, so it’s not a good target from the air. Moreover, it has a lot of small-caliber guns. To engage and defeat a destroyer under steam, that was a real challenge.” And that was the situation when Klenk arrived overhead, looking down at the Hatakaze (“Flag Wind”) with a 1,000-pound bomb in his bay and two, 250-pound bombs hanging under his wings.

A five-plane Helldiver division from VB-80 carried out the attack on the destroyer Hatakaze after a sixth pilot, Ensign Habet Maroot, aborted with mechanical problems. VB-80 skipper Commander Edward Anderson went first, bombed, and missed. Jim Newquist, Bob Mullaney, Chuck Downey, and Ben Case each attacked the Hatakaze with mixed results, including some major hits. Anderson had a “hung” bomb and had to shake it off. The aircraft piloted by Mullaney—later, chief engineer on the Apollo Lunar Excursion Module—was damaged by Japanese gunfire but airworthy.

It looked as if the destroyer was going to elude the dive bombers until it was Klenk’s turn.

He followed the attack sequence drilled into dive bomber crews: “From 10,000 feet, the target slides under the left center section leading edge of your wing,” Klenk said. “You slow down to dive brake deployment speed of 125 knots, turn left with rudder and aileron to take you into a vertical dive, and head straight down at him. You keep your nose on target and release just prior to 1,000 feet of altitude for maximum effect. And then, you pull out, stay low, and run like hell.”

On an earlier mission on November 13, 1944, Klenk witnessed a Helldiver piloted by Ensign John Manchester being blown out of the sky by antiaircraft fire. Manchester and radioman-gunner John Griffith were swallowed up in a ball of flame. Retired Navy Captain Nathan Serenko, a fighter pilot who flew alongside the dive bomber pilots of VB-80 said, “Those Helldiver guys had balls of brass. They went diving right into the dragon’s teeth.”

Klenk’s 1,000-pound bomb went straight down the Hatakaze’s main stack. The destroyer blew up. “The ammunition blew completely,” said

Klenk. “The ship didn’t sink. It just broke into little pieces and disappeared in the explosion. Newquist had hit it and I hit it. One moment, that ship was leaving a wake behind, maneuvering to evade us, and the next moment it was gone. The ship disintegrated.”

Kamikazes vs the Ticonderoga

Klenk and his squadron mates were aboard Ticonderoga when two kamikaze suicide aircraft hit her off Formosa a week later on January 21, 1945. Some 144 sailors lost their lives and the ship was saved only through the heroic efforts of many. A pilot who’d recently left VB-80 for other duties was among those killed. Klenk had vivid memories of a smoke-filled ready room, burning planes on deck, and sailors heaving aircraft and bombs overboard to deter fires from spreading. The damage took Ticonderoga temporarily out of the war. Klenk’s squadron mates Anderson and Mullaney were among those too badly wounded to remain in the war. But Squadron VB-80 was intact and transferred to USS Hancock (CV 19). Klenk and his squadron mates flew combat missions against the Japanese home islands until Hancock’s cruise ended in May 1945.

“That’s One Invasion I’m Glad Didn’t Happen”

Helldivers flew 18,808 combat sorties in the Pacific, sank or helped to sink 120,000 tons of Japanese shipping, and shot down 41 Japanese aircraft. Some 271 Helldivers were lost to antiaircraft fire and 18 to Japanese fighters.

By then, Bill Klenk was in another squadron, VB-15, stateside, preparing to fly the Helldiver during the invasion of Japan. “That’s one invasion I’m glad didn’t happen,” said Klenk, who lives today in Gibsonia, Pennsylvania.

In a fitting salute to the end of their participation in the war, some Curtiss SB2C Helldivers participated in the massive flyover of the surrender ceremony on the battleship USS Missouri (BB 63) in Tokyo Bay September 2, 1945

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments