By Stephen J. Ochs, PHD

On the morning of April 18, 1945, amid street fighting in rubble-strewn Nuremberg, Germany, 20-year-old U.S. Army Captain Michael J. Daly, who had not slept in 24 hours and was running on pure adrenalin, had one overriding goal in mind: to protect his men.

Pinned down by enemy fire, Daly ordered them to stay put and then went forward alone, “a long-tall boy (6-3),” according to a Mississippi machine gunner in Daly’s company, “running stooped-over with his carbine.” Daly engaged in four single-handed fire fights, killing 15 Germans, silencing three enemy machine guns, and wiping out an entire enemy patrol.

For his conspicuous “gallantry and intrepidity” that day, Michael Daly was later awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman—one of 467 bestowed for action during World War II, 60 percent of them posthumously. Indeed, a member of the armed forces cannot receive the Medal of Honor for simply acting under orders, no matter how bravely he or she executes them. Michael Daly was a member of that select group.

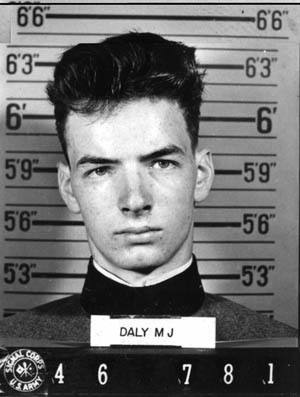

Daly’s heroism was not a one-time occurrence. Rather, it represented the culmination of 11 months of selflessly courageous acts from June 6, 1944, when he landed at Omaha Beach, to April 19, 1945, when he suffered a near fatal wound in Nuremberg. Daly served in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) first as an enlisted man in the 18th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division, and then as an officer in the 15th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Division. During that time, he was awarded two Purple Hearts, the Bronze Star with V attachment for valor, three Silver Stars for valor, and the Medal of Honor. He also advanced in rank from private to captain, and from assistant squad leader to company commander. He embodied a quality absolutely essential to the ultimate triumph of Allied arms: the initiative to close with and aggressively engage the enemy. He did all of this before the age of 21 and on the heels of hell-raising teenage hijinks that led to his dismissal from Portsmouth Priory School and then the United States Military Academy at West Point.

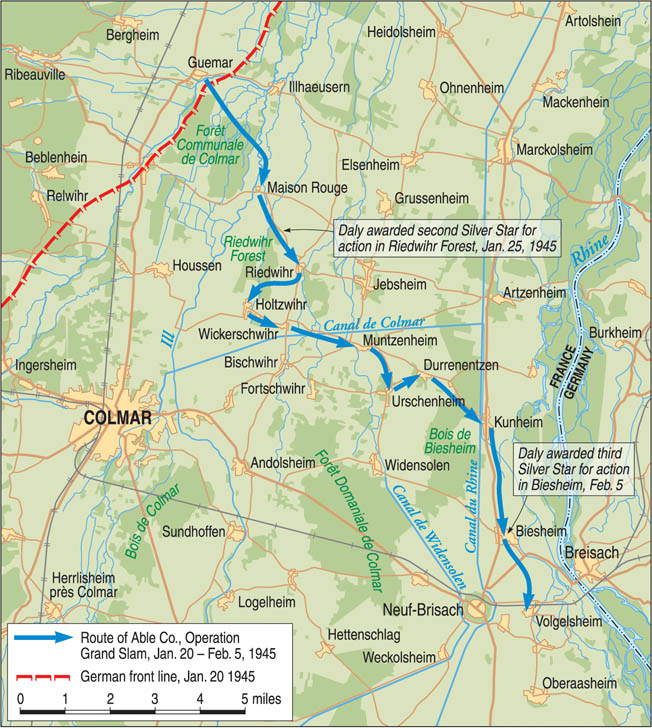

Daly’s path to redemption for his West Point fiasco and other teenage failings would pass through the crucible of an often overlooked but nevertheless brutal campaign on the Alsatian plain in eastern France. Its purpose was to close a German salient west of the Rhine River centered on the Alsatian city of Colmar, France, and known as the Colmar Pocket. The Battle of the Colmar Pocket would last from January 20, 1945, to February 9, 1945. Daly’s development as an officer in the 15th Infantry Regiment during the Colmar campaign previewed his extraordinary actions later in Nuremberg and provided a prism through which to view the closing months of the war in an often forgotten part of the European Theater.

A Troublesome Teenager

Tall and handsome, Michael Daly came from a privileged, lace curtain, Irish Catholic Connecticut family. His father, Paul G. Daly (known by family and neighbors as “the Major”) cultivated the air of a country squire as he practiced law in New York City and raised steeplechase horses on his Connecticut farm. Paul Daly was also a highly decorated officer in World War I, having received the World War I equivalent of the Silver Star, the Distinguished Service Cross, and nomination for the Medal of Honor, among other commendations. The elder Daly sought to inculcate in his son values of courage, patriotism, selflessness, and leadership. He regaled young Michael with stories drawn from military history and from legends and myths.

Mike also learned from his father how to manage fear. Like his father, Mike developed a love for riding horses and eventually competed in the steeplechase. Paul and Mike took long horseback rides together, and horsemanship became an arena for moral instruction and character development.

But hell raising rather than heroism seemed more the order of the day as Mike entered his teenage years, becoming headstrong, rebellious, and self-centered. His father enrolled him in the Jesuit Georgetown Preparatory School, the nation’s oldest boys’ Catholic high school located in the Maryland countryside near Washington, D.C. There, he proved himself a solid student, a likable, popular man on campus (elected president of the senior class), and often a thorn in the side of the Jesuit Prefect of Discipline, the Reverend Bernard F. Kirby. Mike was not mean spirited, insolent, or ill mannered. Most of his disciplinary infractions involved the school dress code, lateness, and hijinks in class.

Off to West Point

Daly graduated in the Prep class of 1941 at the age of 16 and faced an important crossroads. His father wanted him to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point. Mike did not wish to do so, but he never indicated that to his father because he did not want to disappoint him. Since Mike had been advanced from third to fifth grade during his grade school days, he was still too young to attend West Point immediately after high school graduation.

Therefore, Paul Daly, who had subsequently reentered the Army as a lieutenant colonel after Pearl Harbor, arranged for a postgrad year for his son at Portsmouth Priory, a Benedictine boarding school located outside Portsmouth, Rhode Island. There, Daly grew taller and more muscular, played football, did little studying, and capped a desultory semester with an unexcused night excursion to a bar in Portsmouth that resulted in his immediate expulsion.

Nevertheless, because of his father’s political and social connections, Mike was still able to secure a Senatorial appointment to West Point. He also passed the entrance exam for the Academy, one that he had expected to fail. On July 15, 1942, he reported to West Point. He had no problem with the physical rigors of training at the Academy, but he hated the regimentation and hazing that were an integral part of life for plebes. He struggled with math and mechanical drawing in the classroom and bridled at what he perceived to be the arbitrary power wielded by upperclassmen, most of whom he came to loathe. Instead of maintaining a low profile, he took every opportunity to tweak them.

Ultimately, Daly did fail math for the second semester and faced dismissal unless he could pass a reentrance test at the end of the summer. At the urging of his father, Mike enrolled in remedial classes during the summer at the home of a tutor who lived in the Bronx.

“To Hell With This! I’m Going to War.”

George S. Patton IV, a classmate of Mike’s and the son of America’s most flamboyant general, was taking the tutorial also. According to Patton, on a steamy afternoon with the mercury approaching 100 degrees, Daly stood up, threw his books in the corner, and declared, “To hell with this! I’m going to war.”

Eager for combat and yearning for redemption in the eyes of his father for his failure at West Point, Mike enlisted in the infantry. For him, basic combat training at Fort McClellan, Alabama, proved liberating. Freed from what he regarded as the arbitrary and pointless hazing of West Point and already in excellent physical condition—he had grown another inch and now stood at 6-3 and weighed about 190 pounds—Daly excelled. He could see the rationale behind the training regimen at Fort McClellan, even including the tirades by sergeants because they were preparing their men for the rigors of war.

Landing on the Continent

In the spring of 1944, Mike was designated an infantry replacement and sent to Fort Shanks, New Jersey, to await passage to Britain. On arriving in Britain, Mike found himself assigned shortly before D-Day to his father’s old regiment, the 18th Infantry, 1st Division. Paul Daly had pulled some strings to get his son into his old unit and into action as soon as possible. Landing in the second wave at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944, Private Daly pulled a wounded man through the surf and then struggled along with his compatriots across the beach and eventually up the heights.

Within two weeks of landing in Normandy, Daly’s actions exposing himself to enemy fire as a forward observer resulted in his being awarded a Silver Star for valor. He subsequently fought his way from Normandy to Belgium, earning the commendation of his commanding officers for his bravery, combat skill, aggressiveness, and initiative in volunteering for the most dangerous assignments such as taking the point during patrols and serving as a forward observer or as a sniper.

In July 1944, following the Allied breakout from Normandy that shattered Hitler’s armies in the West and sent them reeling across France, Daly and some other decorated American servicemen were tapped to appear on an armed services radio broadcast originating with Ernie Pyle in Paris. As they entered the city, Daly and his compatriots experienced firsthand the jubilation of liberated Parisiennes. A deliriously joyful crowd of young women lifted the Americans from their jeep and passed them over their heads—an exhilarating experience for the 19-year-old Daly. To many, including General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, it appeared that the war might be won by Christmas.

Taking a Commission With the 7th Army

The heady Allied optimism of the summer, however, dissipated as autumn approached and the resistance of German troops stiffened closer to their homeland. Daly experienced this firsthand near Battice, Belgium, on September 6, 1944, when he was wounded in the leg by shrapnel during a mortar barrage. Sent for treatment to a British hospital, Daly was then invited by General Alexander McCarrell “Sandy” Patch, the commander of the 7th Army and a close friend of his father, to finish his convalescence at Patch’s headquarters located in Épinal in the Lorraine region of eastern France.

Meanwhile, throughout the fall of 1944, gloom deepened among Allied forces as they experienced a bloody stalemate all along the Western Front capped by the German counterattack in the Ardennes early on the mistshrouded morning of December 16. Daly was at Patch’s headquarters when the momentous Battle of the Bulge commenced to the north. Patch attempted to return Daly by plane to the 1st Division, but terrible weather thwarted three separate attempts.

Patch, who had recently lost his son in combat, took this as a sign that Daly should be transferred to the Seventh Army. After reviewing glowing reports and recommendations from Daly’s commanding officers, Patch offered Mike a commission as a second lieutenant and a job as his personal aide. Daly accepted the commission but insisted on returning to combat. Patch acquiesced, and on December 28 Mike joined Able Company, 1st Battalion, 15th Regiment, 3rd Division. The regiment was just ending a desperately fought and bloody, five-day battle for control of Sigolsheim, a town on the western Alsatian plain just east of the last line of the Vosges Mountains.

Holding Ground “At All Cost”

Daly had become a member of one of the most battle tested divisions in the United States Army. The 3rd had fought in North Africa, Sicily, and at Anzio Beach in Italy, and then had landed in southern France as part of Operation Anvil-Dragoon in June 1944. It had subsequently battled up the Rhône River Valley and through the Vosges Mountains with the rest of the Seventh Army. The commander of the 3rd Division was Maj. Gen. John W. “Iron Mike” O’Daniel. Stocky, gruff, gravel voiced, and outspoken, O’Daniel carried a bayonet scar on his cheek from combat during World War I. O’Daniel’s troops admired him as a man of great personal courage who understood them and who himself had suffered the loss of a son during the war.

On the day Daly joined Able Company, the Germans were resisting fiercely, their artillery and mortar fire reducing Sigolsheim to rubble, but by the next day the 15th Regiment had taken the town. The 15th Regiment’s determined victory had opened the gates to the plain of Alsace to the east. The Ardennes offensive, however, forced General Jacob Devers’s 6th Army Group in the south to halt all offensive operations and extend its front northward. With an attack possible at any time, the 15th Regiment took up defensive positions with orders to hold the recently won ground “at all costs.”

On New Year’s Eve, the German high command launched Operation Nordwind, the southern counterpart to the Ardennes campaign. A major armor and infantry offensive against Patch’s overextended Seventh Army, Nordwind was designed to link up with German forces engaged in the Ardennes. The Germans also forced a crossing of the Rhine River just north of Strasbourg that threatened to recapture that city. A stubborn but flexible defense, however, wore the German forces thin, and by January 25, Nordwind had ended in defeat. Fortunately for Daly, the 15th Regiment sector had remained quiet. The division sat perched in Alsace ready to close a German salient known as the Colmar Pocket.

Daly found the men of his new platoon receptive and friendly, but many expressed astonishment at their new lieutenant’s youth and boyish appearance. “The first time I saw him, he was a tall kid,” remembered Sergeant Troy Cox. “He had wavy hair when he took off his helmet. I couldn’t believe he could be an officer and a leader.”

While some of the men of the regiment were seasoned veterans, Daly had also demonstrated his own mettle as a warrior during his four months of combat from June to early September 1944. The members of his platoon knew he had served as an enlisted man, had seen combat, had received the Silver Star and the Purple Heart, and had attained an officer’s commission, all of which increased his credibility with them.

Operation Cheerful: The Colmar Offensive

In January 1945, following the defeat of Hitler’s counterattacks, General Eisenhower ordered General Devers and his VI Corps in Alsace to launch a major offensive (Operation Cheerful) to eliminate the Colmar Pocket. This German salient west of the Rhine River, which took its name from the city of Colmar, measured 45 miles at its base on the Rhine and extended 25 miles into the Vosges Mountains. The perimeter around the pocket, which measured 130 miles, enclosed 850 square miles. Creating a 50-mile gap in the Rhine front of the First French Army, the German presence in the pocket threatened the rear of both the Third and the Seventh Armies and thereby the entire Allied position in Alsace. It also drained Allied troops from what Eisenhower considered the more important front farther north, where he hoped for a deep breakthrough into Germany.

The American and French forces sought to strike the pocket simultaneously from the north and south, push along the Rhine plain, and then pinch off the salient, thereby cutting off, trapping, and eliminating an array of German units that had concentrated west of the Rhine. Committed to holding the Colmar Pocket, the Germans brought in the elite 2nd Mountain Infantry Division from Norway and ordered their forces to hold the salient.

At the beginning of the Colmar offensive, Daly and the men of the 3rd Division found themselves attached to II Corps of the First Army under French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. In addition to German arms, Daly and his men faced a formidable foe in the weather. De Lattre graphically described the situation faced by both the Allied and German forces during the Colmar campaign as “frightful,” and almost impossible to imagine.

Closing the Colmar Pocket also required offensive operations in terrain ideally suited to defense. Small villages, towns, and extensive wood patches dotted the flat Alsatian plain that spread eastward from the base of the Vosges Mountains to the Rhine. In addition, numerous canals, irrigation ditches, and unfordable streams crisscrossed the area. German troops armed with Panzerfaust shoulder-fired antitank weapons posed a deadly threat to American armor.

The offensive called for coordinated attacks on both shoulders of the pocket by American and French forces. The main objective, however, was not the city of Colmar, but rather the town of Neuf-Brisach and the nearby bridge over the Rhine. Neuf-Brisach and the bridge lay seven miles east of Colmar. The Brisach Bridge had proven invulnerable to earlier Allied air attack, and now Devers and de Lattre hoped to secure it and to trap as many Germans within the pocket as possible. The four regiments of O’Daniel’s 3rd Division (7th, 15th, 30th, and attached 254th) would thrust at Neuf-Brisach from the northwest shoulder of the pocket. In an operation called Grand Slam, the 3rd Division would cross the Fecht River at Guémar, then the River Ill at Maison-Rouge, and finally the Colmar and Rhine-Rhone Canals to cut off the city of Colmar, thus assuring its fall. After that, troops would then move southward between the Rhone and Rhine Canals to capture the town of Neuf-Brisach and the Brisach Bridge over the Rhine.

General Siegfried Rasp’s Nineteenth Army

Opposing them were the men of the German Nineteenth Army under the command of General Siegfried Rasp. Rasp hoped to tie down Allied forces west of the Rhine to afford the German Army time to redeploy units to the Eastern Front and to reorganize those units remaining east of the Rhine. The Nineteenth Army had been battered by the U.S. Seventh Army and Free French forces during the Vosges Mountains campaign. Its divisions were understrength, underequipped, and undertrained. They possessed only about 65 operational tanks and assault guns.

Still, Rasp had some advantages that would allow him to slow the Allies. He possessed some 22,500 highly motivated troops, whereas the Allies thought he had only 15,000. His army, moreover, possessed plentiful supplies of mines, food, and small-arms ammunition, the advantage of short interior lines of communication, a secure rear area, and the ability to transform the numerous small Alsatian towns into formidable defensive strongpoints. And then, of course, there were the great equalizers: weather and terrain. The Colmar Pocket would be no Allied cakewalk. Of that, Daly and the men of Able Company needed no convincing.

The Maison-Rouge

On January 20, the I Corps of the French First Army began the operation, attacking northward from Mulhouse in a driving snowstorm with strong armor and infantry forces. This action drew armor of the German Nineteenth Army and the arriving 2nd Mountain Division to the southern part of the pocket. Two days later, on the night of January 22, the anniversary of the Anzio landings in Italy, O’Daniel committed his 3rd Division in Operation Grand Slam. In the early morning hours, the 7th and 30th Infantry Regiments with the 15th Regiment in reserve staged a surprise crossing of the Fecht River at Guémar before the Germans could react and then positioned themselves for an attack to the south. By noon the 7th and 30th had captured Ostheim, cleared the Colmar forest, and arrived at the River Ill, which the infantry crossed using rubber boats.

Troops of the 30th then proceeded down the east bank of the Ill and, after a brief skirmish with a small detachment of German troops, captured a 100-foot-long timber bridge and, about a mile away, a crossroads. The location was known as Maison-Rouge because of a nearby farm complex painted red. The Germans believed they had to deny the Allies access to the bridgehead across the Ill because, according to a later Army study, it opened “like the neck of a funnel into the whole area of German resistance around the Colmar Canal,” and once captured “might well become [as it in fact did] the distributing point for American forces pushing to the Rhine.”

Disaster For the 30th Regiment

At Maison-Rouge, however, the Americans encountered near disaster. The bridge over the Ill collapsed under the weight of a Sherman tank attached to the regiment. Until the engineers extracted the tank and repaired the bridge, the troops on the east side of the river had no armor support—a dangerous situation, especially in light of the Germans’ seemingly uncanny ability to extract a terrible price for Allied mistakes.

The Germans showed themselves masters of active defense, ceding ground slowly, stubbornly, and bitterly as they conducted a fighting retreat that battered the Americans with tanks, artillery, and mortars. The German Army built its defensive doctrine around persistent local counterattacks. The units staging these counterstrikes, which varied in strength from company to battalion size, often used tanks and tank destroyers closely integrated with infantry. With lengthening nights and sometimes limited air observation and photography during the day, the enemy could mass forces in an assembly area close to U.S. lines and still avoid detection. Then, taking advantage of the morning fog or haze, they could engage U.S. forces quickly. Enemy artillery fire also increased appreciably, one of the most significant changes since the Normandy operations. The same weather conditions that limited aerial observation and photography made it more difficult for American artillery to locate and thus neutralize enemy guns.

The 30th Regiment, however, could not delay its offensive while the engineers worked frantically on the bridge over the Ill. It had to coordinate its attack with simultaneous drives by the French on its left and the 7th Regiment on its right. Using a footbridge laid across the Ill north of the helpless tank, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 30th moved south and east across 1,000 yards of snow-white flatland, entering a section of woods on the outskirts of the villages of Reidwihr and Holtzwihr. Unfortunately, fierce resistance elsewhere had held up both the French and the 7th Regiment, leaving the 1st and 3rd Battalions with dangerously exposed flanks and facing a powerful enemy. At 4:30 pm the hammer blow fell. The Germans counterattacked ferociously with infantry and armor and routed the 1st and 3rd Battalions, which had no supporting armor of their own.

1st Battalion Readies For a Counterattack

On receiving news of the disaster that had befallen the 30th, O’Daniel sent the 15th Regiment hurrying to the site of the footbridge over the Ill. He instructed the regiment to assume the mission of the 30th and to counterattack at once even though he knew that his infantry, absent armor, would be chewed up. He believed, however, that he had no choice. He had to try to keep the enemy at bay while the engineers repaired the bridge and could not let the Germans seize the initiative and concentrate their power.

At 3 am on January 24, Companies I and K of the 15th Regiment’s 3rd Battalion moved across the Ill to press the attack and suffered the same results as the 30th on the previous day. At about noon on January 24, Daly’s 1st Battalion entered the fray, with his Able Company in reserve. Still lacking armor, they moved into the woods north of Riedwihr and were crushed, albeit with far fewer casualties than the 3rd Battalion had suffered. The 1st Battalion had maintained an orderly retreat because it had been able to call in supporting artillery fire. By late afternoon, the 1st Battalion had regrouped and was preparing to counterattack, this time thanks to the repaired bridge, accompanied by tanks and tank destroyers and by a ferocious artillery barrage that sent shells into roads, junctions, and trail crossings in the Riedwihr woods.

Daly Leads an Organized Retreat

In his first combat role as an officer, Daly led Able Company as part of the 1st Battalion thrust southward from the road junction at Maison-Rouge in an attack on the woods. As Daly later recalled, the forest was dense, and though most trees were bare of leaves in the winter there were evergreens. Maintaining formation in the woods proved difficult. To do so, a man had to keep the soldier next to him in sight. Because the Americans were pressing the offensive, they were more vulnerable to ambush. When those attacks occurred, GIs would fire into bushes and at trees, but often they were unable to see the Germans who were clad in their winter-white parkas and pants— “spook suits”—that blended into the snowy terrain. Sometimes fighting involved individual duels between American and German soldiers separated by a few yards, each sniping at the other from behind trees. Sometimes, hand-to-hand combat ensued. Tree bursts from German artillery proved especially lethal, sending flaming branches and red hot shrapnel to the forest floor.

As it happened, both Able and Charlie Companies ran into fierce opposition from enemy infantry and tanks at the edge of the forest, became disorganized, and suffered heavy casualties as the Germans employed a large number of tanks. Daly found himself in a desperate situation and momentarily confused about whether to fight or to flee. He hated to “let people down by retreating” but realized that he had to extricate his men from the woods so that they all could live to fight another day. He gave the order to pull out and made sure that his men, running downhill as fast as they could in knee-deep snow, got out. Then he followed them. Paul Daly would have approved.

Daly described the withdrawal as “urgent,” not “panic stricken.” Although the Germans did not pursue the Americans out of the woods, they did keep firing at them, hitting several more of Daly’s troops. When Daly and company reached the Ill River, they had to swim or ford the stream. Icicles dripped from the soaked uniforms of the shivering men. Daly felt relief at having extricated his platoon from an untenable situation and at having gotten them to safety, but he felt embarrassment at having being shot at in retreat. His first major engagement as an officer had ended in near calamity. Armored battles raged throughout the night as Daly’s platoon and the whole company, much reduced in size by casualties, regrouped.

German Armored Counterattack

All companies in the battalion had suffered numerous casualties and found themselves seriously weakened. When Able and Charlie Companies were combined, for example, they still numbered only a handful of men. In that precarious condition, the 1st Battalion dug in at the edge of the woods. Reorganizing the scattered companies took almost all day.

At midmorning on January 25, German infantry, accompanied by armor, counterattacked Able Company, which lacked both armor and antitank weapons. The Germans breached the line, driving some men back and isolating others while opening a gap through which their infantry tried to move. Daly’s platoon sergeant, Kenneth W. Johns, however, remained in his foxhole and defended his position with his carbine against heavy small arms and automatic weapons fire from infantrymen seeking to exploit the opening. Six hours of grueling battle ensued, at the end of which the remaining men of Able Company forced the Germans to withdraw, even though one of their tanks continued to roam about in the woods shooting up whatever it found.

Capturing Riedwihr

By 3 pm on January 25, the 15th Regiment prepared to attack again. The 3rd Battalion would take Riedwihr while the 1st and 2nd Battalions eliminated resistance in the northeast and northwest woods, respectively. The drained 1st Battalion had only 60 riflemen, with Able and Charlie Companies still merged. In the dark of night, Daly led 24 of his men 300 yards against a strongpoint at the edge of the woods that consisted of dug-in troops around a machine gun.

The Germans often located strongpoints in an opening in the woods or near a wide path where supporting troops dug in. Sometimes they were backed by mortars or one or two tanks. Advancing to within 30 yards of the German machine gun and “with bullets striking inches away from him,” Daly killed the gunner, enabling his men to capture the weapon. He then led his platoon 300 yards over “heavily shelled and bullet-swept terrain” to clear the objective in three-quarters of an hour.

Twenty Germans died in the attack, and “many more were captured or wounded through his [Daly’s] inspiring and aggressive leadership.” Daly “went after the other guy and it was every man for himself.” The next day, he and his men helped repulse yet another German counterattack of infantry and armor. Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion took Riedwihr.

“Inspiring Attack”

After the capture of Riedwihr, Daly and another man from Able Company trudged their way to Maj. Gen. O’Daniel’s headquarters for a regimental awards ceremony. On a snowy field, O’Daniel pinned an oakleaf cluster representing a second Silver Star on Daly’s jacket. He made some encouraging comments and then asked the lieutenant if he was “ready to go back in there and get this thing over with.”

Mike’s mumbled “I think so” was less gung-ho than O’Daniel had hoped for, and he made his dissatisfaction apparent. But this rolled off Daly’s back. The laconic second lieutenant had nothing to prove; his actions said it all. Numbed by cold, fatigue, and combat, Daly and his companion turned around and made their way back through the snow to company quarters. The headline in the Bridgeport newspaper back home read, “Lieut. M.J. Daly of Fairfield Cited for ‘Inspiring’ Attack.”

In two days of fighting against continuous counterattacks and stubborn resistance, the 15th Regiment had saved the Ill River bridgehead, broken through the German defense, pushed south over difficult terrain, and established a line from which the offensive could be carried across the Colmar Canal to the immediate front. But the regiment paid dearly in casualties among officers, NCOs, and enlisted men. Some companies numbered only 15 men. Many 3rd Division veterans of the Anzio beachhead pronounced the fighting in the Colmar Pocket, especially around Maison-Rouge, as “just about as severe as anything they had yet gone through.”

The Bloodiest Month in Northwest Europe

Indeed, in the Colmar Pocket a dark mood prevailed. Daly recognized that in addition to brutal combat and high casualties—January would prove the bloodiest month for casualties in northwest Europe—the cruel winter weather of the Colmar Pocket endangered not only his men’s health, but also their morale by increasing the physical and psychological difficulties of military operations. Daly looked back on the Colmar Pocket campaign as his most difficult combat, the dug-in veteran German units, the death and wounding of his men, snow and cold, the frostbite and trench foot. “We had to fight the weather as well as the Germans,” he later recalled.

“Some genius decided that we would wear white sheet covers for camouflage,” Daly remembered, “but the damn things flopped around, got wet, and then froze at night,” making movement difficult and sleep impossible. Daly and many others quickly discarded the sheets.

There seemed no escape from the cold. Trigger mechanisms on rifles froze, as did oil on the weapons. When troops slept on the floors of abandoned schoolhouses or warehouses, they curled in the fetal position, hands clasped together and pressed between the knees. Essential clothing included long johns and gloves (or trigger-finger mittens), along with knit woolen caps and scarves, windbreaker trousers to be worn over the standard olive drab, and M1944 Shoepac boots. With leather uppers, rubber lowers, and moisture-absorbing insoles, these boots provided far better protection against water, especially in static positions, than the standard combat boot. But the early versions, which had no heels and gave no support to the arch of the foot, proved terrible for walking. The “paddle-foot shuffle” seen in the ranks of American infantrymen that winter signified not just bulky clothing, inadequate arch support, and numbed or frozen feet, but also psychological demoralization.

By March 1945, more men were missing from the lines because of trench foot than for any other reason. The 46,000 cold weather injuries constituted 9.25 percent of all casualties in the European Theater, the equivalent of more than three divisions. Daly later recalled “the constant challenge” that feet presented. He and his fellow platoon leaders and their NCOs minimized the incidence of trench foot in Able Company by insisting that the men change their socks regularly and by personally seeing to it that they did.

Operation Kraut

Fearing an American breakthrough, the Germans mustered what reserves remained east and southeast of Jebsheim. The Americans, however, shifted southward to the Colmar Canal, a 50-foot-wide, six-foot-deep waterway with 12-foot embankments and slow-moving water that had not frozen. The canal passed just north of the city of Colmar, connecting it with the Rhine River to the northeast. Well-dug emplacements protected the canal, and the fortified towns of Muntzenheim and Bischwihr lay nearby. These proved no match, however, for Allied air power and artillery. Allied planes bombed for two days, and on the cold, clear night of January 29, eight battalions of artillery pummeled the target area.

As a result, in an operation dubbed “Kraut,” Allied forces quickly crossed the Colmar Canal and made short work of the dazed, disorganized force on the opposite shore. Daly’s Able Company, held in reserve along with the rest of the 1st Battalion during the initial crossing, later led the 1st Battalion across the footbridges to join in the broadening offensive to clear the remainder of the Colmar Pocket and isolate the city of Colmar. The Americans would accomplish the latter task by occupying the area east and south of the city to the Rhine River. In the face of the combined American-French offensive, with the Americans driving to the center of the pocket and the French increasing pressure at both the northern and the southern ends, the Colmar Pocket began to disintegrate. As the German 2nd Mountain Division was ground down and then shattered, the 15th Regiment and the rest of the 3rd Division “encountered only scattered, piecemeal units and no cohesive battle order or defensive organization.” Those piecemeal units, however, remained deadly.

“An Interminable Series of Local Collisions”

In the first hour of February 1, the third phase of operations opened with an offensive to the Rhine designed to cut the pocket in two. This meant crossing yet another strategic water barrier, the Rhine-Rhone Canal, which ran in a north-south direction. Able Company’s objective was to take the bridge leading into Kunheim. During the first phase of the attack through the Durrenentzen woods west of Kunheim, all company officers senior to Daly became casualties. He took command of Able Company and pressed ahead toward the town.

The Germans were well armed with tanks, artillery, mortars, and rockets and committed themselves to defending the approaches to the bridge. They had created strongpoints at its foot by sending reinforcements to man thick walled houses just west of the span. A 24-hour battle ensued. After several hours, word arrived that the French had taken Artzenheim and its bridge a mile and a half north, making seizure of the bridge at Kunheim unnecessary. The 15th Regiment objective changed from crossing the canal to clearing Germans from the area up to the canal and from the bridge itself.

As Daly and Able Company attempted to traverse a clearing near the bridge at Kunheim, they encountered a withering hail of machine-gun and small-arms fire as well as heavy mortar concentrations. Daly extricated his men from their untenable position, reorganized them, and then led them on a new route through woods infested by determined German opposition. Staying in the lead, Daly encouraged his men and impelled them forward in the face of a hail of fire until he found it impossible to move farther. He then directed his men to dig in and hold their ground. He personally supervised and checked the placement of their positions, enabling them to withstand intense fire from the fearsome German 88mm guns that night.

Daly’s company also suffered numerous casualties as a result of machine-gun fire directed from tanks at a range of 150 yards and barrages of 150mm rockets, known to GIs as “Screaming Meemies,” fired from Nebelwerfers, combination mortar and rocket launchers. The firing abated in the early morning hours, and at dawn Daly discovered that the Germans had withdrawn under cover of darkness, leaving behind many casualties.

Coming off the line, Daly moved his company into a former German barracks in the woods. There he thoroughly reorganized the men after their engagement, painstakingly checking their equipment and seeing to it that they were able to rest and bathe. The next day he turned over a fresh, victorious, and tightly organized fighting unit to the returning company commander. Meanwhile, the 7th Infantry had taken Kunheim after the battered German forces withdrew from the town.

Daly, however, had no sense of elation or victory. When one town fell there was always another, and then another, and another after that. Max Hastings captured the nature of battle in northwest Europe when he described it, not as a clash of mighty armies after the fashion of Waterloo or Gettysburg, but rather as “an interminable series of local collisions involving a few hundred men and a score or two of armored vehicles, amid some village or hillside or patch of woodland between Switzerland and the North Sea.”

The Death of Joseph Daly

On the morning of February 3, Daly and his men returned to action, moving southward the three or four miles between Kunheim and Biesheim along a slushy, muddy road flanked by fields and interspersed with enemy pillboxes.

The 1st Battalion was charged with eliminating enemy forces in the rear of the 7th Infantry, some of whose units were engaged in the town of Biesheim, where fighting grew more intense. The Germans knew that if Biesheim fell, Neuf-Brisach, the communications center, could not hold out. Its capitulation in turn would sever key communications and supply lines, sealing the fate of the Colmar Pocket and providing the Allies a possible springboard into Germany. The combat that ensued, including street fighting, bombing, and strafing by Allied planes, and artillery barrages from both sides, reduced much of Biesheim to rubble.

Daly’s company pushed to approximately 200 yards north of the town, when fire from three or four machine guns, manned by what was characterized as “fanatical infantry,” hit the flanks and the front, pinning down the forward elements. There ensued one of the most harrowing nights of the war for Daly. It also highlighted an ugly reality and leadership challenge faced by company officers such as Daly in the war’s final months, the fate of 18-year-old “greenhorns” pressed into service as combat replacements because of manpower shortages. One such youngster bore his lieutenant’s last name.

Private Joseph Daly joined the platoon in the midst of the battle for the Colmar Pocket and was clearly frightened, insecure, and inexperienced. Daly tried to reassure him and told him to stay close to his sergeant and do exactly what the sergeant directed. While the company was pinned down north of Bisheim, Joseph Daly suffered a grievous wound to his back. There was no way to evacuate him, and Daly helplessly watched him die a slow, agonizing death as a medic valiantly but vainly tried to ease his suffering and provide some comfort. That scene seared its way into Daly’s consciousness. He never forgot Joseph Daly, whose memory helped inspire Daly’s efforts years later on behalf of the indigent and dying in Fairfield, Connecticut. The terrible experience also reinforced Daly’s determination to do everything he could to bring his men home safely.

Battling Through the Mud

At daylight, Able and Charlie Companies called in armor, and three tanks helped wipe out the enemy positions. The small units of the experienced 3rd Division earned well-deserved praise for their skillful use of infantry-tank teams. In the words of one historian, they “almost unconsciously perfected their … teamwork to a fine art, enabling them to overcome the physical fatigue that most of the soldiers… felt.”

On February 5, the final mission began, moving southward to secure the vital bridges across the Rhine at Neuf-Brisach and thus cut the enemy’s last remaining avenue of escape from the crumbling pocket. Daly and his company, their uniforms covered with so much mud that only the shape of their helmets distinguished them from the Germans, slogged down a slushy road southeast of the village as part of the 1st Battalion’s drive to the south.

After trudging across 800 yards of flat, mucky, open field while enduring fire from 88s and heavy mortars that inflicted numerous casualties, Daly’s platoon spotted a German strongpoint about 200 yards ahead. At a crossroads southeast of the town stood a fortified two-story stone house protected by barbed wire and surrounded by a low stone wall interspersed at intervals with stone columns. At least 25 German soldiers were entrenched about the structure.

Charging Through Deadly Crossfire

Three enemy machine guns opened up and caught Daly and his men in a crossfire. By that time, only nine of Daly’s 22-man platoon remained unwounded. Reacting quickly, Daly directed his men to withdraw down a ditch. Meanwhile, he stood up squarely in the middle of the road, firing his pistol to draw the concentrated fire of the enemy upon himself while his men retreated. For 30 minutes he moved about in plain view of enemy machine gunners and infantrymen armed with the MP40 machine pistol. They fired a hail of bullets at him. As he danced around, they ricocheted at his feet. At the same time he noticed a 15-man German patrol approaching on his flank, and he started firing his pistol at them. Killing two, he alerted his men to fight off the rest. Finally, he broke contact and raced toward his platoon, most of whom were crawling on their hands and knees toward the edge of town and the cover of two machine guns set up there.

Daly, meanwhile, worked his way among the more seriously wounded, who were lagging behind the others, helping and encouraging them. Not until he knew that every wounded man had made it back safely did Daly himself enter the company area. He then gave a concise and calm report on the enemy situation to his company commander. For his action in the road that day, Daly received a second oakleaf cluster on his Silver Star. He felt particularly proud of the Silver Star, later calling it the “infantryman’s or workhorse medal,” indicating valor in a specific instance, not just meritorious service.

Because Daly’s company had not dislodged the Germans from the strongpoint, they once again received orders to seize it. The depleted 60-man company attacked across 500 yards of open field. Troy Cox recalled, “We couldn’t run at all in the mud, and would fall because it was so soft.” When he fell, he also dropped his machine gun into the mire. The quarter-size openings in the barrel meant to cool the weapon became packed with mud, rendering the gun useless, but Cox still carried it as he continued to slip-slide across the field.

The deadly crossfire from the German machine guns and numerous submachine guns mowed down 41 of the men. Only 19 reached the position. When an American tank moved up and blasted a hole in the wall, both the 2nd and 3rd Platoons charged forward in an attempt to storm the opening. But a German gunner on the other side, in combination with the continuing deadly crossfire, repelled two attempts. Finally, rifleman Deland Payne worked his way to within 50 yards of the breach, stood up amid a hail of fire, and blazed at the gunner with his M1 rifle until he killed him.

“Shoot the Bastards!”

After an enemy grenade wounded the commander of Able Company, Daly leaped to the front amid the confusion and led the last assault. Grappling with the nearest German, he shot him dead with his pistol and then ran from man to man, directing them toward German positions. Finally, he led his men inside the stone wall surrounding the house and into the house itself. Firing his weapon, he yelled for his men to “Shoot the bastards!” inciting them to their utmost in the bitter close-range fighting. The result: nine enemy dead, six wounded, and nine prisoners.

A German counterattack ensued shortly thereafter. As fire from enemy self-propelled artillery began wrecking the house, Daly directed his men to dig in and hold the position. The Germans maintained fire on the house, the crossroads, and the roads to the rear in an attempt to deny the Americans use of them. Then, as Able Company fanned out to secure other houses in the area, German tank and artillery fire took them down one after another while continuing to zero in on the crossroads. The company clerk, Sergeant J. Leon Lebowitz, recorded approximately 25 missing or killed in action that day.

While Daly and his company hung on at the crossroads, other companies of the 1st Battalion, along with those of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, captured Fort Mortier, which commanded the northern approaches to the Rhine River bridge sites. The Americans swept southward to the bridges themselves, only to find that the Germans had demolished them.

More Than 4,500 Casualties

By nightfall on February 5, the shelling had ceased, and the 15th Regiment had secured all its objectives. The next night the 30th Regiment scaled the walls of the old fortress town of Neuf-Brisach. The Americans now firmly controlled the designated area east of Colmar, including the approaches to the damaged railroad and highway bridges across the Rhine. A staff officer of the 136th Mountain Regiment of the German 2nd Mountain Division stated that by the first few days of February the German supply system had broken down completely, lack of gasoline being the major consequence.

A captured officer said that large numbers of casualties were the result of accurate and intense U.S. artillery fire. Still, the 15th Regiment suffered 744 battle casualties and more than 1,000 additional casualties from disease, exhaustion, frostbite, and trench foot. The 3rd Division as a whole suffered more than 4,500 casualties. Unable to retreat across the bridges, only 3,000 to 4,000 combat infantry of the now virtually destroyed German Nineteenth Army managed to escape to the east bank of the Rhine. The remnants of the German Army were mopped up, and resistance in the division sector came to an end after the 17-day campaign.

Heroism in “America’s Unknown Battle”

Daly had distinguished himself as a platoon leader during the Colmar campaign, adding two oakleaf clusters to his Silver Star, and his commanding officers sang his praises. Writing on February 7, less than two months after Daly had joined the company, Major Kenneth B. Potter, commander of the 1st Battalion, characterized the young lieutenant’s service as “exemplary, evidencing a very high degree of leadership, aggressiveness, and organizational ability under the most difficult of conditions.”

In recommending Daly for promotion from second to first lieutenant shortly after the actions at Kunheim and Biesheim, Potter not only praised Daly’s initiative in twice assuming command of the company during battle, but also identified essential elements of the young officer’s leadership: “a very high degree of aggressiveness, cool courage and calculated daring, high organizational ability under the most difficult of circumstances, and the utmost devotion to his men both in the height of combat and in the lull ensuing.”

As Daly observed later, “You have to take the chance to get things moving.”

Sergeant Lebowitz snapped a photo of an exhausted Daly returning from a night patrol. He later mounted it into a scrapbook and wrote a caption describing Daly as “the best officer and bravest man I ever knew.”

In the “frozen crust” of the Colmar Pocket, during what one historian termed “America’s unknown battle,” Daly and his fellow citizen-soldiers had prevailed over a battered yet skilled enemy. Famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle attributed the victory to the foot soldiers who had demonstrated “real heroism—the uncomplaining acceptance of unendurable conditions.” Amid those “unendurable conditions,” Daly had mastered the role of platoon leader. Now, he and his men had a chance to rest and to train for the next phase, the battle for Germany that would also include Daly’s rendezvous with the Medal of Honor.

I volunteer at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Bridgeport, CT. The Emergency Room is named the Michael J Daly Trauma Center, so I have been reading about the man Michael Daly. An amazing story, I wish I had met him before he passed.