By William Weidner

With the exceptions of the Normandy invasion and the Battle of the Bulge, few other World War II battles in the European Theater have received more historical scrutiny than the Battle of the Falaise Gap. Yet nearly every account of the battle has gotten it wrong. If you believe that General Omar N. Bradley initiated the “halt order” he gave to George Patton on August 13, 1944, you have it wrong. The Falaise Gap was one of those rare battles that gave both British and Americans a reason for obscuring the truth. How many Germans escaped through the Gap after the Allies bungled the encirclement? It is difficult to say. Everyone who gives an estimate is trying to prove a point. The battle was a huge Allied victory, but it was a less complete victory than it should have been.

The Allies had agreed to appoint an American Supreme Commander for Operation Overlord, the cross-Channel invasion of northwestern France. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt selected General Dwight D. Eisenhower for that role. The British then selected the operational commanders in chief for the Allied air, sea, and ground forces that would serve under Eisenhower. The same system of command had been used in the Mediterranean in 1942 and 1943 with mixed results. It was further agreed that Eisenhower would take command of Allied ground forces when a second U.S. Army (George Patton’s Third) was activated in France.

Historians in the United States have been wrestling with Eisenhower’s role as supreme Allied commander since the end of the war. A group of American senators touring the Mediterranean in 1943 asked the critical question: “[Andrew] Cunningham commands the naval forces. [Arthur] Tedder commands the air forces, and [Harold] Alexander commands the ground forces. What in hell does Eisenhower command?”

The answer to that question had left his supporters worried that the truth would diminish Eisenhower’s historical stature. Historians from the United States do not like to discuss the Falaise Gap because events suggest that Eisenhower did not exercise his command authority; this battle seemed to set the tone for the rest of the campaign.

The Troubled Bernard Montgomery

Through the end of the war in Europe, the British would dispute Eisenhower’s ability to command the Allied ground forces. According to General Bernard L. Montgomery, very few senior American or Canadian Army officers were up to British standards. He wrote to his friend and mentor, Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir Alan Brooke: “Ike is apt to get very excited and talk wildly—at the top of his voice!!! He is now over here [in Normandy], which is a very great pity. His ignorance as to how to run a war is absolute and complete; he has all the popular cries, but nothing else.”

Montgomery was easily the most popular general in the British Isles. His was also a troubled personality. Biographer Nigel Hamilton suggests that Montgomery’s ornery nature could be traced to his “will of steel and a fundamental inflexibility of mind.” He also suggests that the source of Montgomery’s unusual personality was an unloving and sometimes brutal mother. Alun Chalfont wrote that although it is “often misleading to stray into the thickets of psychoanalysis, it is reasonably safe to say that Montgomery became an obsessive personality.” Montgomery’s attempt to control everything seems to have affected all aspects of his life. If Montgomery could control it, he controlled it down to the most infinite detail. If he could not control it, he tried to push it out of his mind.

Empathy was one emotion Montgomery seldom experienced. R.W. Thompson wrote of the field marshal, “His eccentricities, the pedantry of his military dogmatism, his deliberate isolation and his inability to enter into the problems of others, rendered him peculiarly unsuitable for any cooperative role.” Montgomery’s crippled personality made it almost impossible to achieve the “unity of command” so essential for success on the battlefield. British historians often ignore the Battle of the Falaise Gap because it was Montgomery who was responsible for the “halt order” General Bradley gave to George Patton on August 13, 1944.

“It’s a Madhouse Here”

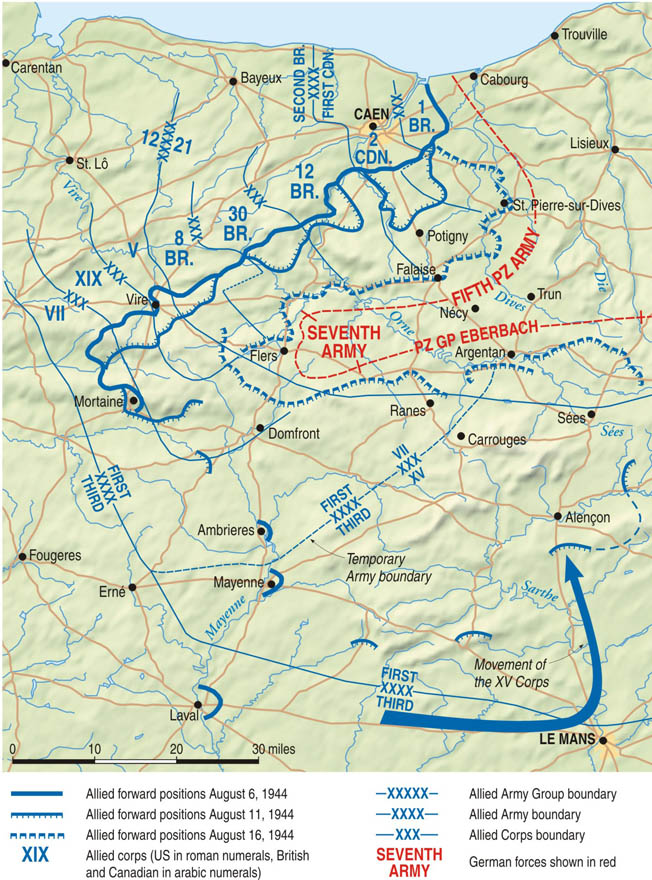

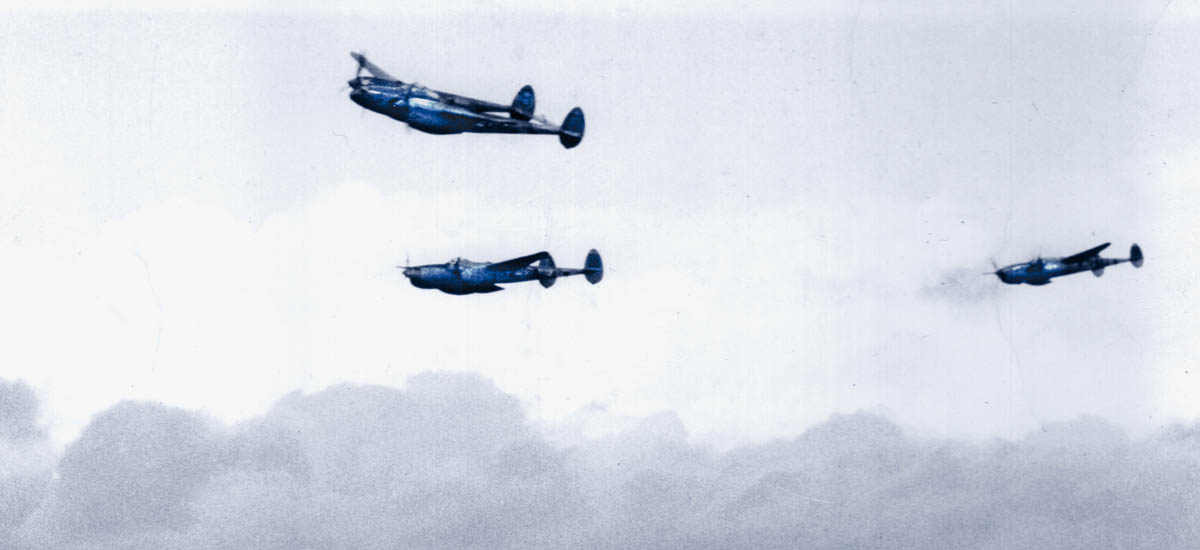

Our story begins after two months of very bloody fighting in Normandy, of very stout German defensive battles on both flanks. Following up the British attack at Caen (Operation Goodwood), the American breakout effort near St. Lô, known as Operation Cobra, finally succeeded in punching a hole in the German line. By July 31, the Americans had turned the Germans’ western flank, and within days General Patton’s Third U.S. Army was driving into Brittany and northeast behind those Germans still fighting in Normandy. The German commander, Günther von Kluge, warned his chief of staff, “It’s a madhouse here.” Adolf Hitler decided against his general’s recommendation for a withdrawal from Normandy. Instead, he saw a chance to save France by counterattacking the Americans at Mortain and driving on to Avranches, cutting Patton’s Third Army off from its supplies.

In spite of General Bradley’s statements to the contrary, the German attack at Mortain on the night of August 6/7 did not catch Courtney Hodges’s First Army by surprise. Thanks to an early Ultra warning, the Americans had plenty of time to prepare for the German attack. Bradley was amazed when he later looked at the maps in his trailer. With elements of Patton’s Third Army driving northeast nearly unopposed into the exposed German southern flank and the German armor attacking west at Mortain, there was a great possibility the Allies could surround and destroy the German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies in Normandy. Bradley’s staff loved the plan.

The following morning, August 8, Bradley tracked down Eisenhower on the battlefield and, in the back seat of Eisenhower’s Packard, sold him on the plan. He asked Eisenhower to return to his headquarters so they could look at a better map and place a telephone call to the commander of Allied ground forces, Montgomery. After Montgomery’s questions about the German Mortain attack were satisfied, he readily agreed to Bradley’s plan to trap the Germans in Normandy. Montgomery said he would direct the Canadians to attack south through Falaise to Argentan while the Americans drove north from Le Mans to Carrouges and Sees. Montgomery also agreed to move the inter-Army Group boundary line north a few miles into the British zone to just south of the Briouze–Argentan–St. Leonard line.

Captain Winterbotham and the Critical ULTRA Intelligence

The preceding paragraphs outline the official Eisenhower, Bradley, and Montgomery version of the Allied decision to destroy the German Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies in Normandy. This version of the event has been adopted by nearly all historians on both sides of the Atlantic. British intelligence officer and Group Captain F.W. Winterbotham offered a vastly different—and far more believable—version of these same events. In The Ultra Secret, Winterbotham related how he recorded an Ultra message on “two whole sheets of my ULTRA paper.…” The date was August 2, 1944. Winterbotham listed Hitler’s instructions to Kluge “in considerable detail, [Kluge was] to collect together four of the armored divisions from the Caen front with sufficient supporting infantry divisions and make a decisive counter-attack to retake Avranches and thus to divide the American forces….”

Winterbotham recalled that he got the intercept to Churchill right away and that Eisenhower thought the message was so important that he had its authenticity checked. Satisfied that the message was genuine, according to Winterbotham, Eisenhower then directed Montgomery to close the trap on the Germans from the north while Bradley and the Americans closed the gap from the south. Winterbotham also wrote, “The opportunity that had been offered to us was such that the decision to alter the entire strategy became one for Eisenhower himself, and I understand it had also to be approved by the joint Allied chiefs of staff.”

Winterbotham says that Bradley was instructed to prepare for the German attack by preparing a “defense in depth in the Avranches area….” Winterbotham also learned that “despite the signals from Hitler, Montgomery was still in favor of an advance on a broad front to the Seine….” Although it differs significantly from the Eisenhower-Bradley version of these events, Winterbotham’s account is far more believable. He was not directly involved in the Allied chain of command in France, and he had nothing to hide. He was simply an impartial observer of vital Ultra intelligence information at a critical phase in the battle. His account has been largely overlooked because it does not follow the accepted version of the Battle of the Falaise Gap.

Captain Harry Butcher, Ike’s naval aide, made an entry in his diary on August 8: “Ike keeps continually after both Montgomery and Bradley to destroy the enemy now rather than to be content with mere gains of territory.” August 8 was the day Eisenhower and Bradley agreed to conduct the short envelopment between Falaise and Argentan. Butcher’s phrase—“Ike keeps continually after both Montgomery and Bradley”—suggests that the possibility of destroying the German Army in Normandy had been available for some time and was not the result of a sudden thought that had popped into Bradley’s head the evening before. Such a scenario also fits more closely with Winterbotham’s account, which suggests that the Allied command had been watching for the possibility of an encirclement for a few days before Butcher’s August 8 comment.

On August 9, Eisenhower wrote to George Marshall, chief of staff in Washington, and explained how he thought the battle would develop: “Patton has the marching wing which will turn in rather sharply to the northeast from the general vicinity of Le Mans and just to the west thereof marching toward Alençon and Falaise.… We have a good chance to encircle and destroy a lot of his forces.” Eisenhower’s mention of Falaise as a goal for Patton’s Third Army is clearly prescient. This was exactly what should have happened. Again, Eisenhower’s letter seems to confirm Winterbotham’s account.

The Politics Behind the Hitler-Kluge Drama

The American hinge at Mortain continued to hold against German counterattacks as Patton’s Third Army poured through along the one good north-south road at Avranches. By the evening of August 7, Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps had three divisions investing Le Mans: 5th U.S. Armored, 79th and 90th U.S. Infantry Divisions. The following day, Le Mans fell to the Americans.

In London, an interested observer was closely monitoring the events in France. British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill had been getting immediate Ultra updates from Winterbotham, who noted that Churchill was getting copies of the German radio messages within an hour of their transmission. The dispatches revealed that the German commander in France, von Kluge, was in an argument with Hitler over the Mortain counterattack. Hitler insisted that the attack must go forward, while Kluge was equally insistent that the attack was beyond the ability of his forces in Normandy and that the Americans were already driving northeast around his vulnerable southern flank.

The argument was transmitted back and forth between German headquarters in East Prussia and Kluge in France by German radio messages encoded on an Enigma machine, which British intelligence (Ultra) was reading almost as easily as the Germans. They had obtained a copy of the “Enigma” coding/decoding machines’ daily settings from a short German airdrop intended for the defenders of Brest a few weeks earlier. Winterbotham later wrote, “Everybody … [including] the Prime Minister, was deeply involved in the Hitler-Kluge drama…. When I was reading these … signals over the telephone to Churchill, I sensed his controlled excitement at the other end. I think we all felt that this might well be the beginning of the end of the war.”

Churchill’s excitement may have been tempered with an understanding that Montgomery’s British/Canadian Army was still stalled north of Falaise and the Americans were about to turn north at Le Mans into a vulnerable German southern flank. The Germans, Churchill knew from the Ultra intercepts, were terribly desperate. They were short of fuel and ammunition and possibly near a total collapse. If the Germans did not reinforce their southern flank in time, the Americans could drive straight through to Falaise. It would appear to the press corps, especially to the Americans, as if George Patton had come to the rescue of the poor British Army, which had stalled only a few miles south of their D-Day objective. Churchill may have sensed that Montgomery had gotten himself into a jam. Churchill was terribly sensitive to press coverage and the political fallout from the battles being fought in France. He resolved to do what he could to help Montgomery.

Churchill’s Bluster Over Operation Dragoon

On August 9, Churchill summoned Eisenhower to 10 Downing Street for another round of heated arguments over Operation Dragoon. The British had been trying to get the invasion of southern France canceled for months, but Churchill’s timing was interesting. It had been only four days since their last arguments over Dragoon, and the invasion was scheduled to go forward in only six days, on August 15. Churchill blustered and bullied the American general. He threatened and he cried. He did his best to intimidate Eisenhower. He said the Americans had become a “big, strong and dominating partner,” and he threatened “to go to the King and lay down the mantle of my high office.” When it was over, Churchill had done his best to browbeat the American general. Eisenhower later described the session “as one of the most difficult of the entire war.” (Read more about the commanders who defined the war inside WWII History magazine.)

Churchill had given a masterful performance, but Eisenhower could do nothing to placate the prime minister’s distress. He remembered that when the meeting broke up, Churchill was still crying. Churchill’s performance won him a deeply personal letter from Eisenhower on August 11: “I would feel that much of my hard work … had been irretrievably lost if we now should lose faith in the organisms that have given higher direction to our war effort, because such lack of faith would quickly be reflected in discord in our field commands.”

Although he was a granite wall against which Churchill hurled his most eloquent pleas, two days later, on August 13, Eisenhower, the “big, strong and dominating partner,” would not challenge the British ground forces commander over an inter-Army Group boundary line dispute at Argentan. Churchill had lost the arguments over Operation Dragoon, but he lost them so gloriously that Montgomery now had a more forgiving boss, a boss who would be very sensitive to British political interests for quite some time.

Seizing Crossings Over the Orne River

On August 9, Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s U.S. XV Corps received two new divisions: the 2nd French Armored and 80th U.S. Infantry Divisions. Patton also gave Haislip verbal orders “to change the Corps’ direction of advance to the north and capture Alençon [with the German Seventh Army’s Supply Depots].” XV Corps sent its 106th Cavalry Group to the area of La Ferte Bernard with the mission of reconnaissance and protecting the corps’ eastern flank. The 80th, after assembling near St. Hilaire, was trucked to the vicinity of Le Mans, where it was to secure the bridgehead there and protect the left flank and rear of the corps by holding the road centers at Sille-le-Guillaume and Evron.

Early that morning, 5th Armored Division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Lunsford E. Oliver, received a warning order from Haislip changing the direction of his attack to the north. Oliver sent his 85th Cavalry Squadron to reconnoiter the Orne River lowlands and bridges. Late that afternoon, orders came through from XV Corps Headquarters: 5th Armored was to drive north, “seize crossings over the Orne River, and continue north to the Carrouges-Sees line.”

These orders also contained information about the other units involved in the attack. Oliver’s 5th Armored was to be followed closely by Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche’s 79th Infantry Division; one regiment of the 79th had been fully motorized so that it could keep up with the armor. Their left flank would be covered by the 2nd French Armored Division, commanded by the feisty Maj. Gen. Jacques-Philippe Leclerc, which was then assembling near Vitre. The French tankers would be followed closely by Maj. Gen. R.S. McLain’s 90th U.S. Infantry Division, which also had one regiment fully motorized.

Oliver of 5th Armored decided to attack that night. Combat Command A [CCA], commanded by Brig. Gen. Eugene A. Regnier, was soon in a fight with elements of the German 9th Panzer and 708th Infantry Divisions for control of the five Orne River bridges near Ballon. Combat Command B [CCB], commanded by Colonel John T. Cole, on the division’s right flank, cleared Le Mans and was ordered to assemble near Bonnetable and be prepared for further movement. Combat Command Reserve [CCR], commanded by Colonel Glen W. Anderson, drove a few miles past Ballon to Marolles-les-Braults and seized five more river crossing points.

Closing in on Argentan

The next day, August 10, Leclerc’s division caught up with 5th Armored. “They took over the task of holding bridges taken by CCA and also placed a column on CCA’s left flank.” Throughout the day, CCA was heavily engaged with elements of the 9th Panzer Division at Marolles-les-Braults while CCR was battling other elements of the same German division in a firefight near Mamers. According to Lt. Col. Emmanuel Cepeda’s report, “It was a case of draw fire, deploy, establish a base of fire and maneuver for the entire day…. Darkness and fatigue called it a day. CCA and CCR were blooded.”

The morning of August 11, 5th Armored received orders to bypass enemy resistance at Mamers and Marolles and drive toward Sees. That evening additional orders said to continue the attack north to Argentan and to cut communications to the north.

Sees was taken on August 12 by the combined efforts of CCA and CCR at 12:10 pm. This engagement included dispersing a battalion of Germans overtaken on the road to Sees. Just as 5th Armored’s CCA left Sees heading north toward Argentan, they ran into the point of a column of the 116th Panzer Division that had apparently intended to enter Sees from the west and northwest. Elements of the 1st SS and 2nd Panzer Divisions were also in the area.

In a running firefight that lasted for several hours that afternoon, Regnier’s CCA used massed tanks and artillery to destroy the elements of 116th Panzer that had been blocking their way. Shattered remnants of the German formations were sent reeling back to defensive positions and reformed on the high ground near Argentan.

That evening CCA approached Argentan from the southeast. By 7:00 pm, “CCA was on the edge of their goal, Argentan, just south of the Orne River.” Apparently it was decided that it was not feasible to continue the attack at night because CCA withdrew to higher ground to the southwest that overlooked the town. “Patrols were successful in getting into Argentan during the night and they reported intense tank and infantry activity.” Meanwhile, Oliver had sent two task forces to cover his division’s eastern flank. The division’s history says, “Task Force Boyer dug in for the night at Exmes. Task Force Hamberg established a road block at the road junction five miles south of GACE by 2100 hours.”

German Vulnerability at Argentan

The German defenses in Argentan on August 12 were not coordinated because their senior officers were out of contact with the units they commanded. Many of them, like Heinrich Eberbach, ran out of messengers during the battle. Eberbach later wrote, “No report had arrived from 116th Panzer Division; whether Sees was still in our hands was not known.”

Later that afternoon Eberbach received a report that indicated the 116th Panzer Division had run into stiff resistance on its way to Sees. “In a subsequent report which reached headquarters in the evening,” Eberbach wrote, “we learned that those advancing elements of 116th Panzer Division had been destroyed by heavy artillery fire from masses of enemy tanks and also that the enemy was forcing his way towards Argentan.” Sees was being defended by a company of bakers. The 9th Panzer Division had been reduced to “one infantry battalion, one artillery battalion and a half-dozen tanks.” Remnants “of the 708th German Infantry Division and the 6th [Parachute] Division were on their way to barricade the area of Gace-Laigle.” The German southern flank had been shattered by Haislip’s powerful XV Corps.

On the night of August 12/13, German defenses in the vicinity of Argentan consisted of one antiaircraft regiment, weak security elements, and the remnants of 116th Panzer that had escaped destruction on the road to Sees earlier that day. The Germans could count no more than 80 tanks on a front of over 45 miles from Briouze to L’Aigle, and many of those tanks were immobilized. They were terribly short of fuel and ammunition since XV Corps had overrun the German Seventh Army’s Supply Depots at Alençon.

According to British intelligence, the German defenders at Argentan were close to a complete collapse. Winterbotham noted, “We knew that what was left of Eberbach’s armor was virtually immobile; he was short of ammunition and fuel. It looked as if the American corps [Haislip’s XV Corps] could close the gap.”

For four days, from the evening of August 12 through the arrival of II SS Panzer Corps on August 16, the southern German flank at Argentan-St. Leonard-Gace lay vulnerable to Allied attack. What was obvious to British intelligence at the time is also obvious to historians; the only reason the German southern flank held for so long was the “halt order” given to Patton on August 13.

Mobile elements of the 2nd Panzer and 1st SS Panzer Divisions arrived during the night of August 13/14, but their protective infantry shield did not arrive until the following day. It was not until the arrival of the II SS Panzer Corps on the 16th that Eberbach considered his defensive positions fairly adequate. But no sooner did they arrive than II SS Panzer Corps was gone, sent out of the pocket on the night of August 17 to Vimoutiers to prepare for the attack that, it was hoped, would hold open the last German escape routes between Trun and Chambois.

The Arrival of Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division

Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division was driving toward Ecouche-Argentan on Haislip’s western flank. On August 12 they occupied Carrouges. Leclerc sent one combat command left of the Forest of Ecouves, one down the middle of the forest, and the other on the right, where they got tangled up with CCA of 5th Armored Division. By midday on August 13, 2nd French Armored had made excellent progress, CCB was covering the crossroads at Castelle, and CCR was a little late after their encounter with elements of 9th Panzer on the road through the center of the forest.

Leclerc arrived with his division headquarters and CCA at the inter-Army Group boundary between Ecouche and Argentan, ready to continue the attack. General Jacques Leclerc, like George Patton, believed that the attack of XV Corps from Argentan to Falaise should have gone forward.

That afternoon a detachment of 60 soldiers from the 10th Company, 3rd Tchad Foot Regiment, 2nd French Armored Division, walked into Argentan by way of the back paths to see “how many Jerries there are in the northern part of the town between the town hall and the Falaise road junction.” The afternoon patrol reported, “Argentan seemed deserted. Two or three reconnaissance cars … a few not very aggressive infantrymen.” Other reports indicated German tank activity in Argentan, but French soldiers from the 3rd Tchad Foot completed their patrol without losing a single man.

Montgomery’s Orders to Remain in Le Mans

Bradley and Patton had planned on using Maj. Gen. Walton H. Walker’s XX Corps to cover Haislip’s left flank and Maj. Gen. Gilbert R. Cook’s XII Corps to cover his right flank. Neither of these corps was available for that purpose, however. On August 11, Montgomery ordered Bradley to withhold a corps of at least three divisions in the Le Mans area in preparation for the wider Seine envelopment, should the Germans try to escape the Allied trap being set between Argentan and Falaise.

Cook’s XII and Walker’s XX Corps remained at Le Mans on Montgomery’s orders until late afternoon on August 14. This represented a fundamental disagreement with General Eisenhower, Montgomery’s boss, who had asked his generals to destroy the enemy on their front, rather than simply occupy ground.

Montgomery’s orders to Bradley on August 11 also produced an immediate argument from Bradley. The flavor of the argument was picked up by Bradley’s aide, Chester Hansen, and faithfully recorded in his diary: “There is some discussion now concerning an alleged disagreement in strategy between Brad and Monty concerning the timing for this northward movement. I am told that Monty is anxious that the continued movement toward Paris in seizure of more terrain, while Brad is equally insistent that we turn north now at Le Mans and trap the German army containing the hinge of the 1st Army and those elements following the 30th and 12th Corps in the 2nd British Army.”

Bradley had remarked that he was concerned about Haislip’s [XV Corps] open left flank, and later wrote, “On the afternoon of August 12, as Haislip’s forces closed on the ‘boundary’ near Argentan, Ike came to my CP to monitor Haislip’s progress, and he remained through dinner.” That afternoon, after securing Eisenhower’s approval, Bradley ordered Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins to drive his VII Corps northeast from the Mortain sector to close on Haislip’s open left flank. Bradley believed that VII Corps were the best troops he had in Normandy.

Although Eisenhower and Bradley did not record much of their conversation on the evening of August 12 for future historians, Bradley later admitted that they did discuss Haislip’s open flank. Bradley would probably have mentioned Montgomery’s orders of August 11 that instructed him to withhold three U.S. divisions in the vicinity of Le Mans in preparation for the wider envelopment. The two generals would have also discussed Montgomery’s change in plans from their August 8 telephone conversation, when Montgomery had verbally agreed to conduct the short envelopment between Alençon-Argentan-Falaise. Now, in a move that mystified Bradley, Montgomery was apparently going to send the Americans off to the Seine while the Germans were still fighting in Normandy.

A First-Hand Account of the Controversial Halt Order

With the sudden disagreement in tactics, one might have expected that either Bradley or Eisenhower would pick up the telephone and talk to Montgomery. Amazingly, neither Eisenhower nor Bradley later admitted discussing the issue with Montgomery. Indeed, Bradley states categorically that he never asked Montgomery to allow the Americans to move north of the inter-Army Group boundary line at Argentan.

The historical record says otherwise. Thanks to detailed notes on research conducted by eminent U.S. Army historian Dr. Forrest C. Pogue and one of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group staff officers, we have a firsthand account of the “halt order.” Dr. Pogue conducted the interview on May 30 and 31, 1947. The interview was given by Montgomery’s intelligence officer, Brigadier E.T. “Bill” Williams, who said he was there on the evening of August 12 when the telephone call went through. These are Dr. Pogue’s notes:

“Remember (he) was in Freddie’s [De Guingand, Montgomery’s chief of staff] truck near Bayeux when 2nd French Armored made its swing up and crossed the road towards Falaise. Monty said tell Bradley they ought to get back. Bradley was indignant. We were indignant on Bradley’s behalf. De Guingand said, ‘Monty is too tidy.’ Freddie thought Bradley should have been allowed to join the Poles at Trun. Monty missed closing the sack. Bradley couldn’t understand. Thought we were missing our opportunities over inter-Army rights. However, it should be pointed out that Monty regarded Bradley was under his command; therefore his decision was not made on the basis of inter-Army considerations … Master of tidiness. He was fundamentally more interested in full envelopment than this inner envelopment. We fell between two stools. He [Montgomery] missed his chance of closing at the Seine by doing the envelopment at Falaise. Monty didn’t want to do the short hook.

“Freddie, using my information and his own ideas, persuaded Monty into that with Bradley arguing for it from his angle. Monty didn’t want to do it but saw a chance to pull it off after he had pushed Bradley back. In the first stage he was looking toward a grander basis, and he thought ‘Hell, those guys are excited; they are spoiling the way we are going.’ Then Freddie and Bradley favor the short hook. He agrees, but it’s already too late. So he misses both opportunities.”

Brigadier Williams’s interview with Forrest Pogue is the only firsthand account of the “halt order” at the Falaise Gap that has surfaced. Most other statements about the order are deliberately misleading. The evidence that Montgomery issued the “halt order” is conclusive. Maj. Gen. Sir Francis De Guingand agrees with Williams’s account: “My impressions at the time were that [Montgomery] had been a little too optimistic about the probable progress of 21st Army Group…. It is just possible that the gap might have been closed a little earlier if no restrictions had been imposed upon the 12th Army Group Commander as to the limit of his northward movement.” The only general in Normandy who could have imposed boundary restrictions on the “northward movement of Bradley’s 12th U.S. Army Group” was General Bernard Law Montgomery. Bradley denied that this ever happened, but De Guingand has a solid reputation for historical accuracy.

Stephen Strafford’s Diary

The diary of Air Vice Marshal Stephen C. Strafford is also in agreement with the memories of Brigadier E.T. Williams and Sir Francis De Guingand. In a diary entry from August 14, 1944, he recorded Bradley’s “general intensions. [Bradley] stated that immediately the Germans were pinned in the area west of Argentan/Falaise, he wished to detach a minimum force necessary to complete the tidying up of the Brittany peninsula and the opening of the Brittany ports and then to drive east from Alençon in an encircling movement against Paris through the gap as early as possible. He states that the American forces had little opposition between Alençon and Argentan and had started toward Falaise, but had been instructed by the C-in-C, 21 Army Group to halt on the inter-army group boundary. There had been few German troops in the area when the Third Army forward elements had arrived there and he was confident that the Third Army now held a firm front on the arc to the north of Falaise.”

Bradley confirmed in Strafford’s diary what is obvious from historical research. Despite claims of stout German opposition at Argentan made after the event to cover up the Allies’ failure to close the gap on August 12 and 13, there was in fact little German opposition in front of Patton’s Third Army. According to the German commander, Heinrich Eberbach, “What was left of 116th Panzer Division reached the Argentan area. Together with the antiaircraft regiment, they took up a thin line on both sides of the town and held their positions.”

After the Americans had captured Alençon and Sees, General Eberbach warned Army Group B of “the necessity of an immediate and quick retreat on a large scale because otherwise a complete collapse [of the southern flank] was unavoidable.” The vulnerable Germans were held in Normandy on orders from Hitler until the afternoon of August 16. Their escape could not begin until the night of August 17/18, five days after 5th U.S. Armored closed on the inter-Army Group boundary line near Argentan.

German Rout in the Falaise Pocket

General George Patton was not convinced that Bradley was telling the truth; he saw through the ruse immediately. A few days after his telephone conversation with Bradley’s chief of staff, General Leven Allen, Patton wrote, “I told him … it was perfectly feasible to continue the operation [the drive to Falaise]. Allen repeated the order [from Bradley] to halt on the line and consolidate…. I believe that the order … emanated from the 21st Army Group, and was either due to [British] jealousy of the Americans or to utter ignorance of the situation or to a combination of the two. It is very regrettable that the XV Corps was ordered to halt, because it could have gone on to Falaise and made contact with the Canadians northwest of that point and definitely and positively closed the escape gap.” Patton was right on both accounts. There was very little German opposition in front of his army on August 12 or 13.

The commanding general of the 2nd French Armored Division, Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc, was also bitterly disappointed that the operation was not allowed to go forward. Shortly after the battle, he wrote to Charles de Gaulle, “For several days I really had the impression that I was reliving the situation of 1940 in reverse. Complete disarray in the enemy ranks, columns surprised, etc. The picture of this attack would have been superb had it been decided to close the Argentan-Falaise Pocket. The Supreme Command was formally opposed to it. History will be the judge.” Historians have been too long at their task.

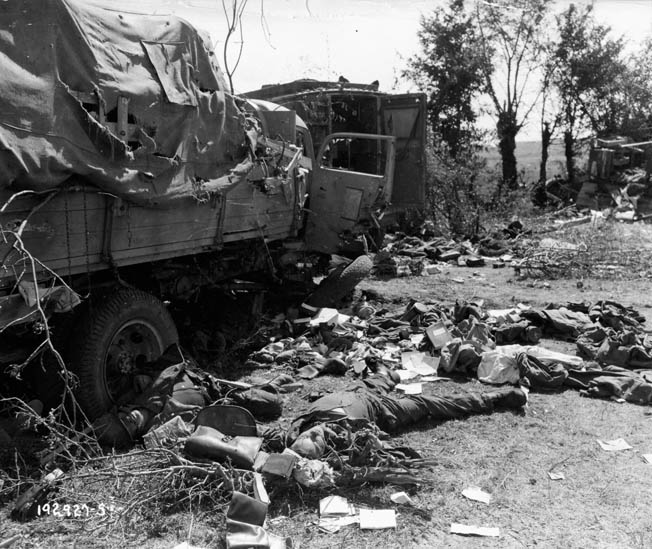

The German commander for their southern flank, General Heinrich Eberbach, spent most of the night of August 12/13 stuck in a traffic jam while trying to move his headquarters from Vieux Pont to Chenedouil. Eddy Florentin wrote, “At Bourg-Saint Leonard, an eyewitness observed an extraordinary sight in the afternoon [August 12]: German vehicles of all kinds, tanks, small and large trucks, motor bicycles and carts fleeing en route for Chambois. This time it was a debacle. Some of the cars had lost their windows, others had no doors left. We saw one, carrying officers, with no front tires and another which had only three wheels.” While joyful French residents watched in amusement, the once-proud German Army was disintegrating into chaos.

The German defeat in Normandy had turned into a rout. Those German soldiers working in the support branches of administration, medicine, and supply were fleeing from the American tanks as fast as they could. Eberbach later wrote, “Catch lines in rear of the front had to be inaugurated. Even the SS was no exception to this rule. The 1st SS Panzer Division had never before fought so miserably as at that time. The fighting morale of the German troops had cracked.” As a result of the chaos within the pocket, many German generals were out of contact with their units.

Eisenhower and Bradley’s Debate on Montgomery’s Halt Order

After Eisenhower and Bradley discussed moving Maj. Gen. Collins’s VII Corps from the Mortain sector to close off Haislip’s open left flank west of Argentan, whatever else they discussed during the evening of August 12 was never made public. They certainly discussed Montgomery’s refusal to allow the Americans to move north of the inter-Army Group boundary line at Argentan. Brigadier E.T. Williams remembered that Bradley was indignant. Bradley liked to have Eisenhower by his side when he talked to Montgomery, for apparently he did not trust Monty. Bradley may have asked Eisenhower what he was going to do about the situation. Although Bradley rarely showed any emotion, this time was probably different. If Bradley had found the courage to get indignant with Montgomery, he was probably not restrained in expressing himself to Eisenhower.

On the evening of August 12, Bradley was trying to decide whether to send Patton north of Montgomery’s arbitrary inter-Army Group boundary line. His final decision was probably not clear in his mind. Two events were continuing to develop that could influence his decision to send Patton north against Montgomery’s wishes.

First, ULTRA had alerted the Allies to an impending German attack against Haislip’s vulnerable western flank. If the Germans hit Haislip hard during the night of August 12/13, Haislip and Patton might be happy to dig in on defensive positions south of Montgomery’s boundary line.

The second outstanding issue was Collins’s VII Corps. How long would it take Collins’s divisions to cover Haislip’s left flank? If Collins ran into trouble during the night, it might be prudent to order Haislip to stop south of the inter-Army Group boundary and prepare for the German attack. But if Collins found few Germans blocking their way and experienced little trouble in closing with 2nd French Armored Division on Haislip’s left, it might be possible to send elements of both VII Corps and XV Corps north side by side in a double envelopment.

Bradley may have thought about giving VII Corps the road axis Ranes-Ecouche-Argentan-Falaise; he would then be required to move XV Corps a few miles east to the road axis St. Leonard-Trun-Fresne. This would have created a double cordon around the Germans. Eisenhower and Bradley may have agreed to delay the final decision on Montgomery’s plan to keep the Americans south of his inter-Army Group boundary line until the next day. They would wait and see what happened to Collins’s and Haislip’s corps over the night of August 12/13.

Haislip’s XV Corps had been cleared to attack up to the boundary line south of Ecouche-Argentan-St. Leonard and cut off the enemy’s escape routes to the east. By the evening of August 12, XV Corps had fulfilled that mission, but nothing was forthcoming from Third Army Headquarters until 8 o’clock that night. Then message No. 4 was sent to: “COMMANDING GENERAL, XV CORPS: UPON CAPTURE OF ARGENTAN PUSH ON SLOWLY DIRECTION OF FALAISE ALLOWING YOUR REAR ELEMENTS TO CLOSE. ROAD: ARGENTAN-FALAISE YOUR LEFT BOUNDARY INCLUSIVE. UPON ARRIVAL FALAISE CONTINUE TO PUSH ON SLOWLY UNTIL YOU CONTACT OUR ALLIES.” The message was probably delivered some time that night.

Early on the morning of August 13, Regnier’s CCA of the 5th Armored Division attacked east of Argentan and suffered heavy tank losses. Apparently the attack got caught out in the open just as the morning fog lifted. CCB was supposed to attack just to the right of CCA, but the attack was called off just before it was to start.

In his “Report after Combat” General Haislip said that he was trying to initiate the attack plan from the night before when orders came through “directing the Corps to halt on the Orne [River].” At one point during the morning General Oliver was warned not to send his men beyond the line Argentan-Gace because a large-scale bombing mission was planned for the area north of that line. Although a series of halt orders restricted XV Corps’ movement to the north, there was no indication that these orders were meant to deny Third Army the authority to cross the inter-Army Group boundary line just south of Argentan.

“The Opportunity of a Lifetime”

Sunday morning, August 13, must have been hectic at 12th Army Group Headquarters. There was a lot going on. The hand-wringing over Haislip’s open flank had come to naught. Eberbach simply did not have the forces he needed to attack XV Corps’ flank; the meager force available to him at Argentan was able to defend itself only because the Americans never attacked it in strength. Historian Russell F. Weigley wrote, “The true reason why the German front held at Argentan was the halt order.”

Just after their staff meeting at around 10 am, Bradley got an excited call from Courtney Hodges of First Army. Hodges told Bradley, “General Collins [VII Corps] called asking for more ‘territory to take.’ The Division was, in some places, on the very boundary itself, and General Collins felt sure that he could take Falaise and Argentan, close the gap, and ‘do the job’ before the British even started to move.”

Hodges was officially endorsing Collins’s request and was asking for an extension of their boundaries so that VII Corps could continue the attack. “But the sad news came back that First Army was to go no further than at first designated, except that a small salient around Ranes would become ours.” Bradley now had two Army commanders [Patton at Third and Hodges at First] demanding a chance at “the opportunity of a lifetime,” a chance to destroy two German armies by completing the drive to Falaise. There were now nearly 250,000 American soldiers sitting on the vulnerable German southern flank.

Bradley was probably mad right down to the tip of his toes; he was past indignant. He did not trust his temper on the telephone with Montgomery, so he asked 12th Army Group’s Operations Officer, Brig. Gen. A. Franklin Kibler, to do it. Then, following orders, Kibler, “phoned Montgomery’s headquarters trying to get permission for Patton to go beyond Argentan. He spoke with General De Guingand … who told him bluntly: ‘I am sorry, Kibler. We cannot grant the permission.’”

Kibler’s telephone call represents the last recorded American attempt to move north of Argentan. At around 10:30 that morning, Bradley left his headquarters and drove straight to Shellburst, Eisenhower’s headquarters, to seek Ike’s help with their “Montgomery problem.”

Bradley Issues the Halt Order

Any questions Eisenhower and Bradley may have had about Patton’s ability to attack north from Argentan and VII Corps’ ability to close on Haislip’s open flank had been put to rest overnight. Neither Bradley nor Eisenhower chose to make their discussions that Sunday morning a part of the public record. The historian must carefully infer what they discussed from what they did after their conversation ended.

Bradley’s concerns about Montgomery’s “halt order” may have poured out to Eisenhower in an emotional torrent. Bradley probably told Eisenhower that the “halt order” was wrong, dead wrong. It was contrary to everything they had learned about military strategy. Bradley likely warned Eisenhower about Patton (who was probably on the phone trying to reach either general) and the American newsmen. If American reporters ever discovered Montgomery’s chicanery, Eisenhower could kiss his precious Anglo-American alliance goodbye.

Eisenhower probably waited patiently for Bradley to finish. Then he told Bradley that he had given their “Montgomery problem” considerable thought. Ike may have told Bradley not to worry about George Patton; Eisenhower would take care of that. But then Eisenhower probably said that he agreed with Bradley about the press. If the American press discovered that the ranking British officer in Europe had ordered two American armies to halt on an arbitrary inter-Army Group boundary line for reasons that defied military logic, the Anglo-American alliance might be shaken to its core. Eisenhower had carefully considered the aftermath and it worried him.

The supreme commander probably thought that it would be too risky to allow Montgomery’s “halt order” to stand as a direct order from the senior British officer in France. He then tried to convince Bradley that it would be politically expedient for them to handle Montgomery’s “halt order” within the U.S. Army’s chain of command. Eisenhower would then have asked Bradley to issue the “halt order” in his name, taking Montgomery out of the controversy. He probably told Bradley to make up any reason he liked for issuing the order. Eisenhower promised Bradley his full support in later explaining the “halt decision.” Bradley probably cringed, but in the end he agreed to do what Eisenhower asked. He would issue the “halt order” to General Patton in his name.

At about 11:20 that Sunday morning, while he was still at Eisenhower’s headquarters, Bradley called his own headquarters and talked to his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Leven C. Allen. He directed Allen to call Third Army headquarters and give them an order to halt on the Argentan-Sees boundary line in his (Bradley’s) name––with the added provision that the boundary line was not to be crossed under any circumstances. At 11:30 Allen, following Bradley’s very specific instructions, called and delivered Bradley’s “halt order” to Patton’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey.

The Cost of Preserving the Anglo-American Alliance

Eisenhower liked to lecture his subordinates about the virtues of destroying the enemy force rather than simply pushing the enemy back and occupying the ground. He was right, especially in Normandy where they had the Germans virtually surrounded. He was also fond of quoting the 19th-century military strategist Carl von Clausewitz, who wrote, “It follows that the destruction of the enemy’s force underlies all military action; all plans are ultimately based on it…. Thus it is evident that destruction of the enemy forces is always the superior, more efficient means, with which other cannot compete.”

Eisenhower had apparently decided that the Anglo-American alliance was worth more than the men whose lives would be sacrificed to the bad tactical decision he had just endorsed.

Ike had refused to take command of Allied ground forces on August 1 when Patton’s Third Army was activated. He cited poor communication facilities at his new headquarters near Granville, but the real reason seemed to be his reluctance to demote Montgomery. Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s willingness to pamper British political sensitivities did little to address the Allies’ main problem. Russell Weigley put it bluntly: “The Allied armies in Europe simply lacked one of the prerequisites of military success, unity of command.”

Over 200,000 Germans Escaped Through the Falaise Gap

How many Germans escaped through the Falaise Gap? The Allies killed 10,000 Germans during the battle and captured another 50,000 after the pocket was closed. Martin Blumenson, using Royal Air Force estimates, calculated that on August 19 there were 270,000 Germans either in the Falaise pocket or heading for the Seine River. Subtracting the German dead and prisoners from this total leaves about 210,000 Germans who escaped through the Falaise Gap. Canadian Maj. Gen. Richard Rohmer comes up with the same total (210,000) in his book, Patton’s Gap.

Allied soldiers paid a terrible price for Montgomery’s failure to destroy the German armies trapped in the Falaise pocket. Russell Weigley wrote, “German higher headquarters for the most part escaped the envelopment…. These headquarters [later] demonstrated the remarkable rapidity with which they could reconstitute divisions and corps around themselves.”

All 10 of the German panzer divisions that fought in Normandy were later reconstituted around cadres of men hardened in battle who had escaped from the Gap. Nine of the 10 reconstituted German panzer divisions would go back into action in December 1944 against Courtney Hodges’s First U.S. Army during the Battle of the Bulge.

General Eisenhower had warned his boss, George C. Marshall, about Montgomery. “Eisenhower reported back to Marshall that … Montgomery’s procrastination had added weeks to the length of the Italian operation and cost the Allies thousands of lives. He now showed every evidence of doing the same in the battles in northwestern Europe.”

Despite Montgomery’s severe limitations, British efforts to wrest command from Eisenhower would continue through the end of the war. It would eventually require every ounce of Eisenhower’s tact and forbearance to save the Anglo-American political alliance. The military alliance, which Eisenhower had worked so hard to protect, was gone. It had been sacrificed to British vanity at the Falaise Gap.

What a difference to the outcome of the war it would have made if the Germans had lost an additional 200,000 men and their equipment in Normandy. Market Garden would not have been necessary. There would have been almost no real resistance all the way to the Rhine. Probably no Battle of the Bulge, and who knows how many lives, both allied and German, might have been spared from future fighting.

You absolutely correct. 2 whole German Armies completely out of the war along with all their equipment. All irreplaceable at that time. How many lives lost in the following 9 months just to assuage Monty’s fragile ego? Tens of thousands certainly.

One would think it would never happen again, lesson learned. Not true though. We delayed again on the trace to Berlin, this time to allow the Russians time to catch up. How different would the cold war have been if we hadn’t done that? Less Communist territory, far less brutal rape and plunder. Possibly afraid of having to having to face the Russians in order to stop their barbarism, but still unconscionable. Any unnecessary prolonging of war is a bad strategy.

A Polish friend ,who has since passed away, was a prisoner of war being held by the Germans in Italy. He had been captured at the start during the German invasion September 1940. He told me that the Germans were allowed to escape at Falaise because a secret deal had been made to free the Polish soldiers held in Italy. I don’t remember where they went. He was a good guy and I believed him.

Pulling Patton’s gasoline to give to Montgomery “British” to take out V2 launching sites – huge mistake. One only has to look at CASUALTIES from September/October 1944 to end of war to show the savings of LIVES on both sides if Patton had been allowed to punch into Germany at that time.

One wonders if Eisenhower wanted the “Allied cooperation” himself so much that he allowed political considerations to overrule common sense, that is, destroying the enemy’s forces being the prime objective to winning the war. Was it only his own decision to let Monty have his way, and prolong the war by allowing those would-be captive German soldiers to escape and fight again at places like Arnhem and Ardennes? Or was Ike himself pressured by political figures above him? Or by standing up to the British primadonna would his own career be endangered? That’s only a question that I ask, with no solid evidence to back it up; just more food for thought. Could Ike have been that short-sighted and missed the long term consequences of that horrible decision, to let Monty save face and let his British-led forces from the stalled northern offensive to close the gap? Shame on whomever was behind that. How many G.I.s and allies’ lives were lost because of those enemy soldiers being allowed to fight later on? If allowed, Patton would have gone as far north as needed to accomplish the goal, but Ike and Bradley let Monty have his way . Maybe it was easier than fighting him behind the scenes. Regardless, that should be a black eye on Eisenhower, and anyone else who pushed for, and worse, allowed, that to happen.

A while back I read an account of the Civil War Battle of the Crater outside Petersburg. The main point being that both Meade and Grant were within viewing distance of the debacle that this battle became. Yet neither general personally intervened because of the inviolable line of command rule. No commander should ever intervene to correct mistakes of his general commands. How can any army perform when the commander intervenes and contradicts orders of his subordinates, no matter how far they strey from his intentions.

Place the responsibility where it belongs on Ike’s shoulders. He knew what was happening was wrong and he did nothing. It really doesn’t matter how wrong Monty was, Ike as his commander was in a position to override him and see that things were followed out to achieve the main goal–the defeat of the Nazis.

Fascinating! I’ve spent some time in the “Falaise Gap”, including the excellent Polish Montormel Museum, as well as other private museums in the area. I had no idea that the Brits were probably responsible for the failure to close the Gap and capture the escaping German armies.

Thank you.

“The Battle of the Generals”_ by General Blumenson makes it clear that Bradley, not Montgomery, ordered Patton to stop at Falaise:

♦ Bradley, on his own initiative, ordered Patton to stop on August 12 (page. 206-207);

♦ Bradley’s post-war effort to blame this on Montgomery was “dishonest and anti-British” (page. 211);

♦ Despite Bradley stating he ordered it. Patton was running off to Paris, but Bradley failed to stop him from making a long hook encirclement of the Germans towards Dreux at the Sein (page. 223);

♦ This was in clear contradiction to Montgomery’s suggestion that he do so (page. 218).

The U.S. Army Official History – Martin Blumenson’s Breakout and Pursuit – attributes the decision not to close the gap to Bradley. Thus the title of the section is BRADLEY’S DECISION (pages 506-509). He states directly: “Montgomery did not prohibit American advance beyond the boundary.” And on page 509: “Bradley himself made the decision to halt.”

The British Official History – L. F. Ellis, Victory in the West, Vol. 1 – attributes the decision to Bradley on page 429.

In Bradley’s memoir A Soldier’s Story he says on page 377, “Monty had never prohibited and I never proposed that U.S. forces close the gap from Argentan to Falaise.” He gives a number of reasons for not pushing north from Argentan, but Monty forbidding it is not one of them.

In A General’s Life Bradley writes, “Montgomery had no part in the decision; it was mine and mine alone. Some writers have suggested that I appealed to Monty to move the boundary north to Falaise and he refused, but, of course, that is not true… I was determined to hold Patton at Argentan and had no cause to ask Monty to shift the boundary.”

Nigel Hamilton, Monty’s official biographer, states in The War Years that the decision was Bradley’s. “Dempsey’s diary record of his meeting with Monty and Bradley proves there was certainly no plot to deny Patton glory, since Dempsey specifically recorded: `So long as the Northward move of Third Army meets little opposition, the two leading Corps will disregard inter-Army boundaries'” (page. 788).

There are plenty of secondary sources that pin the blame on Bradley.

Russell Weigley, Eisenhower’s Lieutenants” page. 216: “Bradley, having set the stage by urging Eisenhower and Montgomery to grasp the opportunity of a short envelopment at Falaise-Argentan, failed to persist in completing his own design. He abandoned the short envelopment before its potential was achieved, and meanwhile he had delayed the long envelopment at the Seine.”

Peter Mansoor, The GI Offensive in Europe page. 171: “Bradley was slow to concentrate sufficient force to close the Falaise Gap from the south when he had the opportunity to do so.”

Robin Neillands, The Battle of Normandy 1944 page. 358: “Bradley’s memoirs and the British Official History make it abundantly clear this decision was Bradley’s.”

There are many more sources where these came from.Carlo D’Este states on page 444, “When Dempsey met Bradley and Montgomery there was apparently no restraint placed on further northward movement by XV Corps… the fact that the Third Army did not move north of Argentan appears to have been Bradley’s choice rather than a prohibition by Montgomery.” On page 448 he writes, “The assertion that Montgomery made no effort to close the gap is without foundation.” D’Este also dismisses the view of Strafford on page 451. No reasonable reading of D’Este on Falaise could possibly support blaming Montgomery. The US Official History, the British Official History, BRADLEY HIMSELF (twice!) and a multitude of secondary sources say Monty did not order Patton to halt. Neither Bradley himself, nor Montgomery, nor the senior British Army commander, nor the British or American official historians think Montgomery ordered Bradley to stop. THERE WAS NO HALT ORDER by Monty.

“THERE WAS NO HALT ORDER by Monty.”

Yes there was. He couldn’t let U.S. forces take something in a few days that the CW forces couldn’t take in months.

The US sadly have history for rewriting history, sane as Nijmegen incident during Market Garden.

They WILL have their very own version of history as they want it. Of course everyone is capable of this including the British, but the Americans have become expert at this.