By Michael E. Haskew

Nathaniel Banks was a political creature, and with his country in the throes of civil war, he now held the politically obtained rank of major general in the Union Army. Three terms as Republican governor of Massachusetts and a tenure as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives may have been impressive in the halls of government, but Banks’s qualifications for military command were nonexistent.

With no military experience, Banks took the field in the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1862 and received his first lesson in tactics from Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who delivered a thorough thrashing to Banks, taking so many wagons and such great stores of supplies that the Confederates mockingly dubbed the neophyte Union commander “Commissary Banks.” The following year Banks muddled through the siege and eventual Union victory at Port Hudson, Louisiana, on the Mississippi River. Now, in the spring of 1864, the 47-year-old political appointee was in command of the Department of the Gulf, based at New Orleans. He hadn’t learned much in the interim.

Putting Pressure on Confederate Exports

By the third year of the Civil War, the Union had gained the upper hand over the Confederacy, but the casualty lists were seemingly endless. Powerful Copperhead politicians in the North called for peace overtures, and Southern pride and combativeness were as robust as ever. Adding a political dimension to the continuing conflict, 1864 was an election year, and when the voters, civilian and military, cast their ballots that November, the world would know the results of a referendum on the administration of Abraham Lincoln and his conduct of the war.

Amid the jumble of political uncertainty, unfinished military business remained, and the Trans-Mississippi West was coming sharply into focus. While the U.S. Navy had maintained a tight blockade of major Southern coastal cities throughout the war, the ports of Mexico were beyond its reach. Ships laden with cargoes of arms, ammunition, medicine, and other precious supplies regularly made landfall in Mexico and offloaded contraband that was hauled overland across the Rio Grande to Texas and eventually into the waiting hands of needy Confederates. In return, Texas cotton was shipped to Europe in trade.

Cotton still wielded considerable influence on the Northern economy as well. The raw material needed to fuel the economically vital textile mills of New England was scarce. The mill owners, their looms virtually idle, were heavily invested in the political scene, and they called long and loudly for the seizure of the cotton fields of East Texas. In that regard, Lincoln and Banks shared common ground. Lincoln courted the support of the wealthy business owners as he stood for reelection. They were also a critical component of Banks’s constituency, and the ambitious general was intent on running for the presidency himself sometime in the future.

Lincoln and his military advisers also worried about the presence of a foreign army near the Texas frontier—not the Mexican Army but a French expeditionary force sent there by Emperor Napoleon III. It was possible, though unlikely, that the French would intervene in the war on the side of the Confederacy, attempt to annex parts of the American Southwest, or regain control of at least a portion of the territory that constituted the old Louisiana Purchase. To dissuade the French from interfering in the war and to capture the much-needed cotton for northern mill owners, it would be necessary for the Union Army to invade East Texas.

The Red River Campaign

With Port Hudson already occupied, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, titular commander of all Union armies in the field, determined that the most logical route for such an invasion was a westward thrust from neighboring Louisiana. A prerequisite to such an offensive was the capture of the city of Shreveport, capital of Confederate Louisiana and the hub of a vital military and manufacturing cluster that included arms production and port facilities on the Red River, a shallow and sometimes treacherous stream that meandered more than 1,300 miles from headwaters in the Texas Panhandle through scrub land, bayou, and swamp to a confluence with the Atchafalaya and Mississippi Rivers. Even during peacetime, the land was inhospitable. Conducting a sophisticated military campaign there would be a daunting task indeed. One Confederate soldier who knew the region well said with disdain, “I would not give two bits for the whole country.”

Banks had long believed that a successful military expedition would enhance his prospects for the presidency, while a failure would doom his aspirations for the White House. Because of that, Banks considered a campaign through Red River country too risky, but unrelenting pressure from Lincoln and Halleck had already forced him to act. In the autumn of 1863, he had made three separate alternative attempts to establish a substantial Union presence in Texas. Offensive actions at Sabine Pass, along Bayou Teche, and at Brazos Santiago near the mouth of the Rio Grande had ended either in failure or only limited success.

Nevertheless, Lincoln remained fixated on East Texas, and Banks’s final attempt to evade a campaign on the Red River in favor of a move eastward against the port city of Mobile, Alabama, was rebuffed by the president despite the support of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who commanded the Military Division of Mississippi and would soon succeed Halleck as overall Union military commander.

Early in 1864, planning began for the largest combined Army-Navy offensive of the war. The ensuing Red River campaign was destined to become a costly, protracted exercise in frustration and futility that battle-hardened, pragmatic Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman would assess, pithily but accurately, as “one damn blunder from beginning to end.”

A Flawed Plan From the Outset

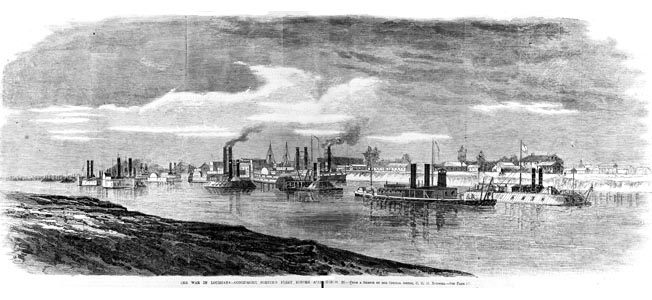

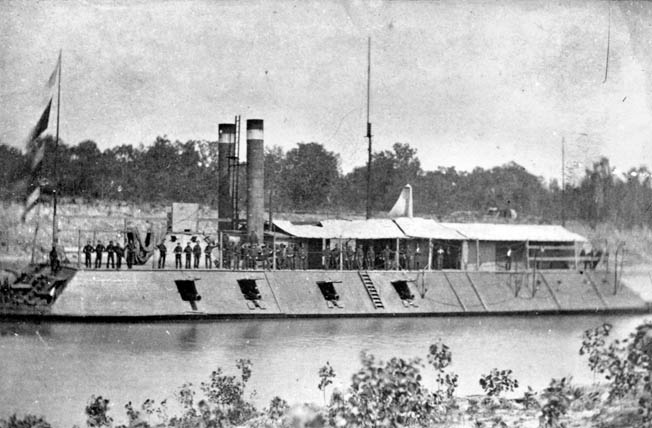

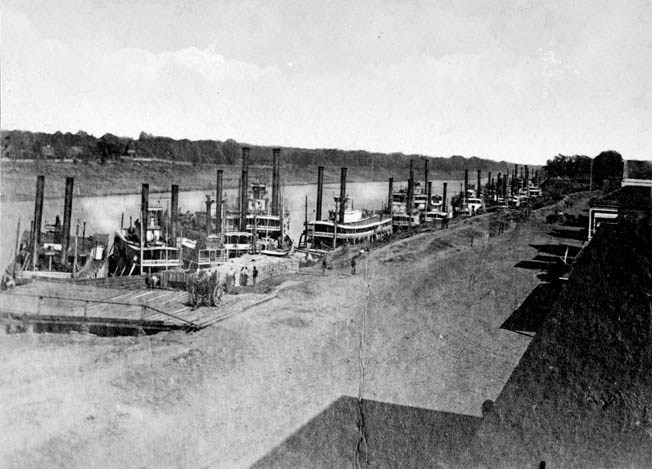

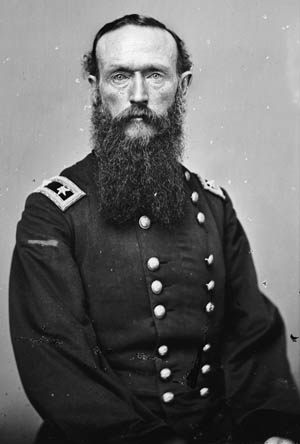

The blueprint for the Red River campaign called for cooperative action between 20,000 Union soldiers of the XIII and XIX Corps under Banks, a powerful flotilla of ironclads, tinclads, wooden warships, and transports mounting more than 200 guns under the command of Admiral David Dixon Porter (who had also expressed concerns of his own about the potential success of the operation). In addition, there would be 10,000 soldiers of the XVI and XVII Corps from the Army of the Tennessee. These last forces, battle-tested veterans under Brig. Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith, were on loan for the Trans-Mississippi operation and due back with Sherman in April to take part in the looming Atlanta campaign. Banks was told that he could also count on an additional 15,000 Union troops slated to march from Little Rock under the command of Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele and join in the effort to capture Shreveport.

With such a powerful force marshaled for the offensive, Banks’s optimism began to rise. He believed that Confederate resistance would be minimal leading up to the actual assault on Shreveport and that the entire operation could be accomplished in about four weeks despite the complexity of the plan. Moving north from the vicinity of New Orleans, Banks would lead the largest force to the railroad junction at Brashear City. From there he would march to Opelousas and then on to Alexandria to rendezvous with Smith’s command and Porter’s flotilla, numbering more than 60 boats. Smith and Porter, in the meantime, would follow the Red River to Alexandria and deal with any enemy resistance encountered during the advance. Once the campaign was underway, Steele would move southeast from Little Rock.

The plan was flawed from the outset. There was no actual unity of command. Each of the three independent Union forces could, in effect, operate autonomously as the tactical situation unfolded. The commands were also widely separated, with more than 400 miles between the northern and southern elements at the outset of the campaign, making it difficult to maintain reliable communications. Most disturbing was the fact that Porter emphasized firepower and seemed to discount the deeper draft of heavier warships. The shallow Red River would prove to be a formidable obstacle to riverine operations.

Nevertheless, on March 7 the vanguard of the Union offensive, a cavalry division, rode forward. Three days later, Smith’s veterans left Vicksburg aboard transport ships headed for the Red River. On March 12, a powerful task force joined the mission from Porter’s Upper Mississippi Fleet, including the monitors Osage and Neosho, each mounting big 11-inch guns; the armored gunboats Carondelet, Essex, and Eastport; and light tinclads Cricket and Fort Hindman. The heavy gunboat Lexington made an impressive sight while underway, and a host of auxiliary and supply vessels, including the hospital ship Woodford, rounded out the largest concentration of naval might thus far assembled in the western theater of the war. Shortly after the warships weighed anchor, Eastport ran aground on a sandbar, an early harbinger of troubles to come.

The Confederate Defenses

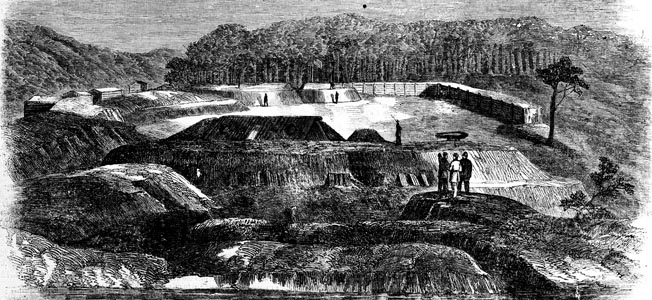

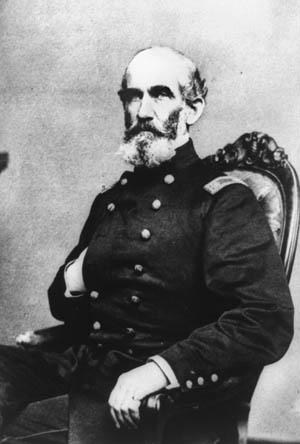

For months, Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, had observed the growing Union activity in and around Louisiana. As the immediate threat began to materialize, Smith ordered troops into position and fortifications prepared to resist the coming offensive. He also prepared to demolish a dam that would divert water from the main course of the Red River to another streambed and had an old steamboat scuttled below the dam to block the river.

A central figure in the Confederate defensive effort was Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor, commander of the Western District of Louisiana and the son of former President Zachary Taylor. Under Taylor’s command in Louisiana were a division of Texas infantry led by Maj. Gen. John Walker and an independent Texas brigade under Camille Polignac, a young French officer fighting for the Confederacy. Smith ordered Taylor to harass the Federal advance, slowing it as much as possible, and instructed Texas cavalry under Brig. Gen. Thomas Green to hurry to Taylor’s aid. Smith also ordered Maj. Gen. Sterling Price to move with several divisions against Steele in Arkansas.

Early Successes of the Red River Campaign

On March 12, Union General Smith’s infantry formations landed at Simsport on the Red River. After establishing a joint Army-Navy supply base there, a coordinated attack was planned on Fort DeRussy, the principal Confederate defensive position in the area. Walker, outnumbered, pulled most of his troops temporarily out of harm’s way, leaving only a token garrison of 300 men to defend the earthworks. On March 14, Porter’s gunboats pounded the position, and a Union infantry division under Brig. Gen. Joseph A. Mower captured Fort DeRussy in a swift assault that suffered only 38 casualties and netted scores of Rebel prisoners.

Capitalizing on his momentum, Porter sent Osage ahead to Alexandria, and as the bulk of the Union land and naval forces drew up, the city surrendered. Taylor was already gone. Some spoils were taken, and a correspondent for Harper’s Weekly watched as “our gunboats seized over 4,000 bales of cotton, and vast quantities were still coming in. Two steamers, with 3,000 bales of cotton, were burned by the Rebels to prevent their falling into our hands.”

Clash Between Banks and Porter

Despite these early successes, the Union timetable was beginning to unravel. Although Porter and Smith had reached Alexandria at the appointed time, they waited for another four days before Banks’s cavalry arrived. Three days later and a week overdue, his footsore infantrymen, fatigued by their difficult march through the swamps of the Bayou Teche, reached the city. Banks arrived in Alexandria aboard a steamboat named Blackhawk, the same as Admiral Porter’s tinclad flagship. Porter was obviously irritated by Banks’s tardiness and was further annoyed by the apparent appropriation of his flagship’s moniker. Banks, in turn, was irate that Navy personnel had helped themselves to much of the cotton he had promised to northern businessmen accompanying him on the steamboat.

Whatever cooperative spirit had previously existed between Banks and Porter quickly eroded. Further complicating matters, the seasonal rise of the Red River, which usually occurred in the winter, had not materialized. Always hazardous, the tortuous course of the river would probably be impassable at numerous points. Banks correctly concluded that without Porter’s naval support the campaign would have to be abandoned—and with it his hopes for the presidential election of 1864. At first Porter declined to participate further, even though he had once boasted that he would go “wherever the sand is damp.” Banks, however, demanded that the admiral continue his mission. Porter reluctantly agreed, muttering that he would do his best even if “I should lose all my boats.”

Oddly enough, the first vessel the admiral ordered up the river was Eastport, the heaviest of his ironclads, which promptly became wedged between jagged rocks. It took three days of backbreaking labor to free Eastport while other vessels squeezed past, their keels dragging sluggishly through the mud of the river bottom. The hospital ship Woodford struck a partially submerged rock with such force that her hull was compromised and the ship sank, taking costly medical supplies with her.

While Porter foundered, the audacious Mower, a Vermont carpenter before joining the Army to serve in the Mexican War and embarking on a military career, struck again. A mixed bag of rain and sleet pelted Mower as he moved toward Henderson’s Hill, more than 20 miles northwest of Alexandria. With a brigade of cavalry, an artillery battery, and six regiments of infantry, Mower struck the drowsing camp of the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry, capturing 250 Confederate horsemen, many of their mounts, and four artillery pieces. Taylor was temporarily blinded by the loss of his cavalry and forced to pull back another 40 miles up the Red River to Natchitoches.

Banks remained concerned about the level of protection afforded by Porter’s big guns and refused to move forward without naval support, squandering an opportunity for a more rapid overland advance. While at Alexandria, Banks received an unwelcome message from Grant specifying that Smith’s troops were to be returned to Sherman by April 15 if it became apparent that Shreveport would not fall before that date. Realizing that time was becoming as much of an enemy as the terrain or the Confederates, Banks, Smith, and Porter set out once more up the Red River.

A “Howling Wilderness”

Taylor abandoned Natchitoches as the Federals approached, and on April 3 Union troops reached high ground at Grand Ecore, 50 miles farther upriver. Smith’s troops left their waterborne transportation, and Banks found himself at a crossroads in more ways than one. While Porter asserted that a reconnaissance along the river, estimated to take three days, was the best course of action, Banks disagreed. He argued that Shreveport could be reached with four days of hard marching and that Smith was scheduled to return to Sherman’s command in less than two weeks.

Banks decided to send Porter upriver to Springfield Landing, just below Shreveport, along with 2,300 men to provide some security against Confederates who were sure to harass Porter’s boats from both sides of the riverbank. Meanwhile, Banks and Smith would march from Grand Ecore toward their objective on the Shreveport-Natchitoches Stagecoach Road. There were no reliable maps of the area at hand, but Banks accepted the risk of his troops marching away from the Red River and the protection of Porter’s guns.

Banks soon became painfully aware that the Stagecoach Road was extremely narrow—in some areas little more than a dirt path. The countryside was increasingly inhospitable, with thickets and brambles interrupted by ditches and ravines. One Massachusetts cavalryman called it a “howling wilderness.” Nevertheless, on April 6 Banks set out, his men turning away from the river. The column stretched more than 20 miles with troops, horses, artillery pieces, and roughly 1,000 wagons streaming westward toward Los Adaes, where Brig. Gen. Albert L. Lee’s cavalry screen, 4,000 inexperienced horsemen who were recently converted from infantry, turned north onto the Stagecoach Road. Banks hoped to rendezvous with Porter at Springfield Landing on Loggy Bayou on April 10.

Compounding the problems of rough terrain and poor roads, the Union force marched in an ill-advised sequence. Behind Lee’s cavalry came 300 heavily laden wagons, at times slowing the pace to little more than a crawl. Behind the wagons came more than three divisions of foot soldiers, then another 700 wagons. Smith’s troops, the most experienced of the infantrymen, brought up the rear of the column. When Lee proposed that the infantry be allowed to pass around the wagons where it might support his cavalry, his request was denied.

Taylor Prepares For a Clash

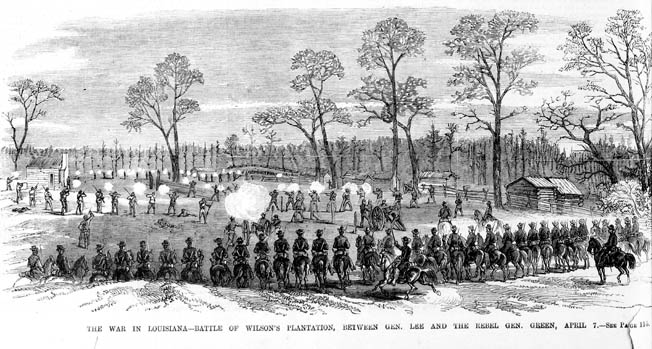

Lee broke camp at Pleasant Hill on the morning of April 7. Just three miles into the day’s advance, his troopers were struck hard by four regiments of Green’s Texas cavalry at Wilson’s Farm. When Federal reinforcements arrived, the attackers melted away. Before dusk, another Rebel cavalry charge took place and was repulsed at Carroll’s Mill. The message was clear—Taylor was no longer falling back. His entire army was probably nearby, spoiling for a fight after a 200-mile retreat.

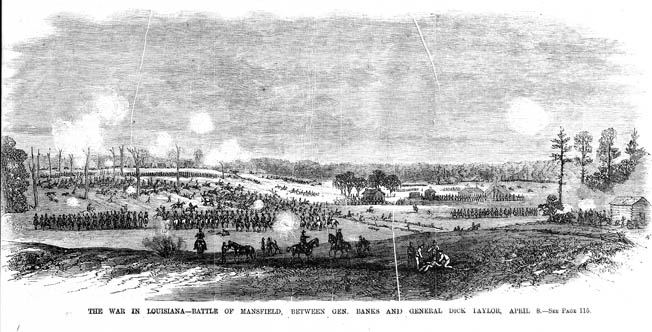

In fact, Taylor’s full complement included Green’s cavalry, Walker’s Texas division, and a division of Louisiana troops under the command of the grandly named Brig. Gen. Jean Jacques Alexandre Alfred Mouton, nearly 9,000 men altogether. At Keatchie, 20 miles away, were 4,400 more Confederate soldiers, two divisions of Sterling Price’s command, Arkansas and Missouri troops led by Brig. Gens. Thomas Churchill and Mosby Parsons. Taylor was still outnumbered 2-to-1, but he was determined to fight at Sabine Crossroads, three miles southeast of the town of Mansfield. The Confederate line was three quarters of a mile long astride the Stagecoach Road. From the concealment of thick woods, an open killing zone 1,200 yards long and 800 yards wide stretched from a point where the road emerged from the tree line.

Early on April 8, Lee was again on the move. Along the crest of a ridge to his front, he spotted Confederate cavalry, which hastily retired after he gave orders to engage. Union horsemen galloped after the enemy troopers, and when Lee reached the crest of the ridge he saw Taylor’s battle line. When probing attacks against the Confederate left held by Mouton’s Louisianans proved fruitless, Lee withdrew, deployed his two accompanying artillery batteries, and requested reinforcements.

Major General William B. Franklin, commander of XIX Corps, ordered Brig. Gen. Thomas Ransom to move his XIII Corps forward and sent along an additional infantry brigade to assist. Ransom, however, was restricted by Lee’s wagon train and struggled to reach the dismounted Union cavalrymen. By 3:30 pm, approximately 4,800 Union troops were on the field, including two brigades of Colonel William Landram’s 4th Division.

Lee’s Rout at the Battle of Sabine Crossroads

Taylor had chosen his ground well to invite a Union attack. Although he enjoyed a temporary numerical superiority he waited several hours for one to materialize. At 4 pm, after Landram had completed his final troop dispositions, Taylor could wait no longer. He ordered his own assault. Mouton’s men charged into the open ground and assailed Landram’s line amid a storm of rifle and cannon fire. The Confederates fell back, regrouped, and came on again. Conspicuously gallant, Mouton was one of several Confederate officers who rode on horseback during the attacks. He was also among 11 of his command’s 14 officers killed in the span of 20 minutes. The division took 700 casualties in half an hour of fighting, losing one-third of its men.

Polignac assumed command of Mouton’s ravaged division and Taylor sent elements of Green’s dismounted cavalry against Landram’s exposed right flank while Walker’s Texans and more of Green’s dismounted troopers struck Landram’s left. As both Union flanks began to buckle, Landram realized he was in danger of being surrounded. Walker’s soldiers captured three Union artillery pieces and turned them on their former owners, who began to withdraw in disorder. In a flash, the retreat became a confused stampede of soldiers and horses running for the rear. Lee later lamented, “In 20 minutes our line was just crumbling everywhere and falling back.”

Half a mile behind their first line, the fleeing Union soldiers ran into a defensive cordon of 1,300 men from the 3rd Division under Brig. Gen. Robert Cameron. They filtered through, and Cameron managed to stand for about an hour before his stopgap line ruptured. Hundreds of Union soldiers were then streaming away from the fight, running headlong into Lee’s wagons and leaving them behind to fall into the hands of Taylor’s onrushing Rebels.

Two miles beyond the unfolding debacle, the 1st Division of XIX Corps was rapidly marching toward the sound of the guns. Its commander, Brig. Gen. William Emory, a combat veteran and West Point graduate, was unfazed by the mob running past him. Emory formed his men in a line at Pleasant Grove along a ridge behind a small stream known as Chapman’s Bayou. Taylor’s Confederates were disorganized and breathless by the time they reached Emory’s line, and their uncoordinated attacks were easily repulsed. After less than 30 minutes the Rebel onslaught was stopped.

Darkness fell and Banks, who had shown considerable valor as he tried to gain control of his retreating troops, counted the cost. The Union force had lost 2,200 soldiers killed or wounded, more than 200 wagons, and 20 artillery pieces. Still, Banks initially wanted to hold his ground and bring up Smith’s veterans to renew the battle the next day. His lieutenants, however, advised an organized withdrawal to Pleasant Hill, where Banks could find Smith with relative ease. The distance was about 14 miles, and by the following morning the Union position around the town was consolidated.

Battle of Pleasant Hill

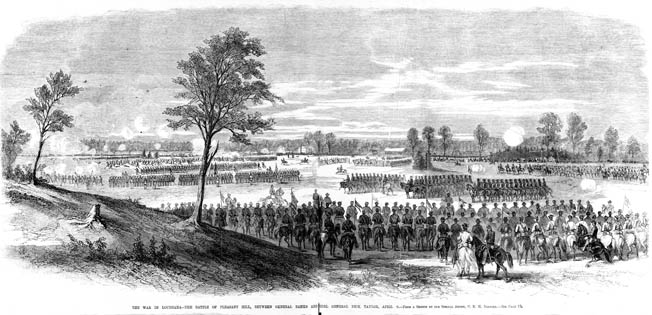

While Banks withdrew, the Confederates happily pillaged the abandoned Union wagons, and by dawn Taylor realized that the enemy had pulled back. Quickly he put Green’s cavalry on the road toward Pleasant Hill, with Churchill and Parsons marching hard behind them. Polignac led Mouton’s former command of Louisianans, and Walker’s Texans, flush with victory, followed.

The Confederates wasted little time, spurred on by Taylor’s belief that he was fighting only the now-battered XIX Corps. By 9 am, Green’s horsemen were within a mile of Pleasant Hill, and from a plateau outside the town they could see Banks and Smith in line between two hills that guarded their flanks with soggy marshland to their front. The Confederate infantry began filtering into the area, tired and parched with thirst. The Missouri and Arkansas soldiers had tramped nearly 50 miles in two days.

While Taylor surveyed the situation, he allowed the winded infantrymen to rest for a couple of hours. At midday, an artillery duel erupted between a dozen Confederate howitzers, many of them captured during fighting in New Mexico the previous year, and a Union battery occupying one of the hills to Taylor’s left. The Rebel fusillade eventually drove the New York battery from its position, and the Confederate commander ordered another attack.

Elements of Churchill’s division moved against the Union left while the big guns were still dueling, charging into a brigade from Emory’s division led by Colonel Lewis Benedict. Momentarily the Union line held, but Churchill managed to slip to the right and outflank Benedict, who was shot dead in the melee. The defense fell apart, and the retreating Union soldiers ran for the dozen or so buildings in the town of Pleasant Hill. Banks’s center was now vulnerable, and Walker, Polignac, and Green, his horsemen again fighting as infantry, dashed into the gap.

Shortly after Churchill attacked, Green ordered elements of his cavalry to charge across the muddy slough and slash into the center of the Union line. The charge soon came to grief as the Rebel riders were caught by flanking fire from an adjacent wooded area. Meanwhile, the rapidly deteriorating situation on his left brought Banks to the brink of disaster. Churchill’s troops were nearly into the town itself and threatened his rear. Whooping as they continued to charge, the Rebels took little notice of the long blue line of Smith’s veterans on their right. At an order, they rose up and delivered a punishing volley, followed by a charge that pushed Churchill’s surprised troops back into Walker’s men, who were battling in the center of the Union position. The resulting combat was brutal, hand-to-hand at times, but as daylight began to fade Rebel resolve ebbed as well. Some of the weary Confederates fled in disarray.

Taylor took tactical control and ordered the bulk of his command to retire to the vicinity of a small stream six miles to the rear. Other soldiers stayed on the battlefield throughout the night, collapsing where they stood and finding fitful sleep. Taylor had lost more than 1,600 killed, wounded, or captured during the momentous day, and another 1,000 had been lost at Sabine Crossroads the previous day. Although Banks had suffered nearly 1,400 casualties on April 8 and lost nearly 4,000 men in the two battles, the Union had greater numbers available to renew the fight.

Banks Abandons His Dead and Wounded

As the clock reached midnight, Kirby Smith arrived from Shreveport. A bit unnerved by the situation, he later reported, “Our repulse was so complete and our command was so disorganized that had Banks followed up his success vigorously he would have met but feeble opposition to his advance on Shreveport.”

Banks held another council of war, and Andrew Jackson Smith was virtually alone among the Union officers favoring a stand and renewal of battle the next day. He believed that a major victory had been won in spite of the fact that he never agreed with Banks’s troop dispositions or his conduct of the battle once the shooting began. Smith considered Banks incompetent and even suggested to General Franklin that Banks be arrested.

In a show of “military democracy,” Banks allowed the majority to rule and subsequently ordered a withdrawal. Three days later, the last Union soldier had trudged back to Grand Ecore. Shamefully, Banks failed to gather his dead and left his wounded on the field at Pleasant Hill. He threw up earthworks, sent a message to Porter asking for the fleet to join him with much-needed supplies, and waited.

Taylor and Kirby Smith had been at odds since the beginning of the prolonged defense of northern Louisiana. Taylor believed Smith had withheld the vital reinforcements from Price’s command for too long. Now he was convinced that with Banks separated from Porter’s gunboats and his supplies running low, he could bag both the Union Army and Navy contingents if his superior would allow him to pursue Banks to Grand Ecore. Kirby Smith, however, would have none of it. Despite the fact that the tactical draw at Pleasant Hill had become a strategic victory for the Confederacy with Banks’s retreat, Smith ordered the divisions of Walker, Churchill, and Parsons to return to Sterling Price to counter Steele’s Union forces moving from Arkansas.

Taylor was furious. Left with only about 5,000 troops, comprised largely of Green’s cavalry and Polignac’s depleted division, the best he could do was slow Banks down should the Union commander continue to fall back from the Red River country or resume the offensive.

Chaotic Retreat of the Union Navy

Meanwhile, Porter reached Loggy Bayou unmolested but facing the hulk of the scuttled steamer that Smith had set across the Red River above the landing. When word of Banks’s defeat at Sabine Crossroads and his retreat from Pleasant Hill reached the admiral, Porter became alarmed. Without Banks and his infantry, the Union flotilla was in danger of being cut off and captured in the confines of the river. Porter ordered his fleet to retire from Loggy Bayou. Navigation was nearly impossible in the shallow waters, and the need for speed caused several unfortunate incidents. Confederate snipers took potshots at anyone who moved on the deck of a Federal gunboat, and Porter fretted while his flagship pulled the ironclad Chillicothe free after it had run up on a submerged log. The big gunboat Lexington and the smaller warship Rob Roy collided, and the transport Emerald ran aground on the sandy riverbank.

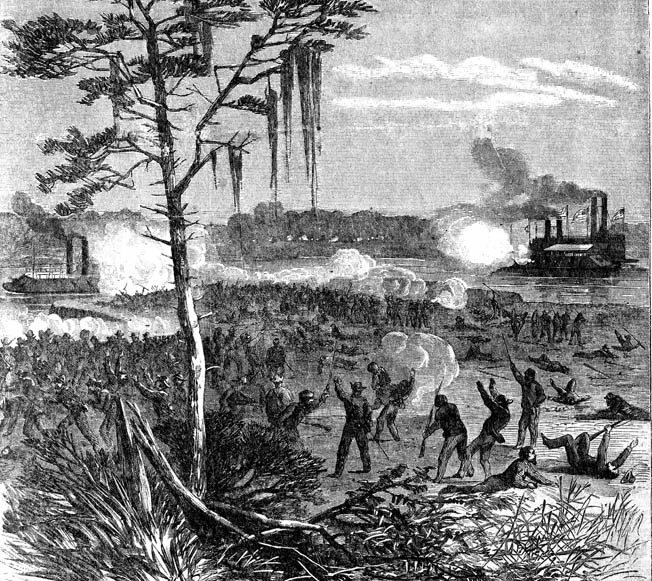

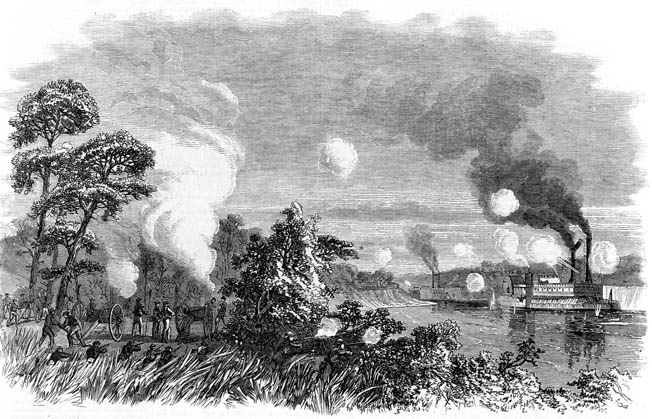

At Blair’s Landing, 45 miles up the river from Grand Ecore, a Confederate battery of four guns and 2,500 cavalrymen under the dashing Texas horseman Thomas Green lay in wait for Porter, hoping to bag the entire flotilla. On April 12, Green’s artillery and rifles opened fire on the transport Hastings, tied to the shore while undergoing repairs to her damaged wheel. The captain of Hastings cast off to escape the heavy enemy fire, and Osage, dispatched to assist the transport, ran aground. Once again, Porter was in the thick of the action as his flagship Blackhawk jerked the monitor free.

Confederate shells pounded the transports Alice Vivian, Emerald, and Clara Bell, while Lexington, Rob Roy, and Osage fired their heavy guns in a heated exchange with the Rebel cannons. The fight lasted two harrowing hours before the Confederates were compelled to retire. When it was over Porter ruefully wrote, “The woodwork of the Blackhawk and Osage was so pitted with bullet holes that it is no exaggeration to say that one could not place the hand anywhere without covering a shot mark.”

The Confederates too were not unscathed, losing seven men, including one towering presence, the gallant Green, who had been decapitated by a Union shell. Taylor approvingly noted, “His death was a public calamity and mourned as such by the people of Texas and Louisiana.”

When the last of Porter’s flotilla reached Grand Ecore on April 15, one New York infantryman observed, “The sides of some of the transports are half shot away, and their smokestacks look like huge pepper boxes.” Miraculously, although battered, no Union ships had been lost during the arduous trek.

Steele’s Blunders

To the north, Steele’s expedition from Little Rock had gotten off at a glacial pace, departing on March 23, a full 10 days after Grant had ordered the advance to commence. Harried by Confederate cavalry, Steele constantly worried about supplies as he crossed country that was devoid of potential food and water. A rendezvous with a force of 5,000 troops from the Army of the Frontier under Brig. Gen. John M. Thayer marching from Fort Smith, Arkansas, did not materialize until several days after the appointed time. When the two forces finally did unite, supplies were scarce, and Steele was forced to detour through heavy rain and over roads that turned to rivers to the town of Camden, Arkansas, on the Ouachita River.

Steele and Thayer slogged into Camden on April 16 and promptly sent out foraging parties to fill nearly 200 wagons with much-needed provisions. As they returned to Camden two days later, the Federals were overwhelmed by marauding Rebel cavalry under Brig. Gens. John Marmaduke and Samuel Maxey. Some of Maxey’s troopers were Choctaw Indians, and the hapless Union foragers included several African American soldiers from Thayer’s 1st Kansas Regiment. When the one-sided fight was over, every single wagon was put to the torch. Dead and wounded Union soldiers lay scattered about. Later, the Confederates were accused of murdering the black troops while the Choctaws were denounced for allegedly scalping some of their victims.

Steele, suffering from indecision, had been idle at Camden for a week when he discovered the infantry divisions of Churchill, Parsons, and Walker drawing near Camden and received the distressing news of Banks’s defeat at Sabine Crossroads. On April 25, Steele suffered another stunning blow when 1,600 troops escorting a train of supply wagons to Pine Bluff were set upon by 2,500 Rebel cavalrymen. A staggering 1,300 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured in the daylong battle at Marks’ Mill.

Steele concluded that his position at Camden was hopeless and that continuing south toward Banks was probably a journey toward further disaster. He ordered a general retirement to Little Rock. The retreating Federals fought off harassing Rebel cavalry and marched to Jenkins Ferry on the Saline River. Heavy rains slowed the effort to cross the river, and the next morning Kirby Smith ordered Churchill’s men to assault a heavily defended line of breastworks not far from the banks of the Saline. The ill-advised attack cost Smith about 1,000 killed or wounded, while Steele suffered another 700 casualties. Three days after the Battle of Jenkins Ferry, Steele’s tattered ranks trudged back into Little Rock, their harrowing ordeal having accomplished nothing.

Harassing Banks With Horsemen

After their rendezvous at Grand Ecore, Porter and Banks remained at odds. Banks considered a renewal of the drive on Shreveport, but he finally realized that the prospects for success were virtually nil. The Red River was becoming shallower by the hour, and Sherman was impatiently demanding the return of his troops. Porter wanted to extricate his flotilla from the confines of the Red River, and Banks knew that he could not proceed northward again without the support of the gunboats. On April 19, the retreat to Alexandria began. Smith’s Army of the Tennessee troops brought up the rear of the Federal column, burning Confederate warehouses full of supplies and plundering homes and businesses along the route.

Taylor was as aggressive as his limited resources allowed, sending cavalry ahead of Banks to harry the enemy and setting a trap at Monett’s Ferry on the Cane River. Green’s cavalry, now under the command of Brig. Gen. John A. Wharton, pressed the Union rear, and Taylor ordered his infantry to march toward flanking positions on both the left and right of Banks’s command.

As Emory’s division, leading the Federal withdrawal, reached a steep embankment along the river, his soldiers ran into dismounted Rebel cavalry blocking their line of march. Banks sent some of Emory’s troops on a two-mile march to the right, where they were forced to wade across the shallow river as alligators slithered into the brackish water, then countermarch to strike the flank of the entrenched Confederate horsemen.

The Confederate commander, Brig. Gen. Hamilton Bee, was duped into believing that he was on the verge of being flanked and ordered his 2,000 troops to withdraw. Bee’s blunder allowed Banks to extricate himself from the jaws of Taylor’s trap and proceed to Alexandria. Furious at the failure, Taylor continued his relentless pursuit and drew his troops close to the city. Banks ordered the preparation of two defensive lines and waited for word of Porter’s progress.

The Union Navy’s Continued Misfortunes

The troubles for the naval flotilla were far from over. Just below Grand Ecore, the gunboat Eastport hit a Confederate mine and sank in shallow water. Sailors worked for hours manning steam pumps and patching the hull with timbers, eventually refloating the vessel. Eastport’s guns were removed to lighten its load and placed aboard a raft that was towed by the tinclad Cricket, which took up a rearguard position. Eastport was taken under tow by the transport Champion No. 5, but the following evening the hapless gunboat ran aground again. Another day was lost as sailors worked to free the warship. Their satisfaction was short-lived. Just two miles farther downstream, Eastport stuck fast on a snare of logs and rocks.

While the tinclad Fort Hindman labored in vain to free Eastport, Rebel sharpshooters peppered the decks of both ships. Finally, Porter faced the inevitable. Eastport would never complete the journey down the unforgiving Red River. While the rest of the flotilla pressed on to Alexandria, the admiral ordered eight barrels of gunpowder set beneath each casemate to blow the ship to pieces rather than allow her to fall into enemy hands. The shattering explosion nearly swamped the launch Porter was aboard as he observed the disheartening proceedings.

With his flag now aboard Cricket, Porter sailed on with only Fort Hindman and another tinclad, Juliet, and the transports Champion No. 3 and Champion No. 5. They traveled 15 miles and ran a gauntlet of enemy cannons and rifle fire from 200 Rebel infantrymen and four guns downstream. Artillery shells raked the vessels, and 48 sailors aboard Cricket, over half its crew, were killed or wounded. Each of the ships took shell hits and casualties. One shell ruptured the boiler aboard Champion No. 3, scalding to death 100 newly freed slaves who had come aboard from surrounding plantations.

On the morning of April 27, as the riddled warships tried to get underway again, the Rebel guns opened up once more, pounding Juliet and Fort Hindman. Champion No. 5 was abandoned, and Champion No. 3 was thoroughly wrecked. Osage came up to render assistance, and Fort Hindman and Juliet managed to survive.

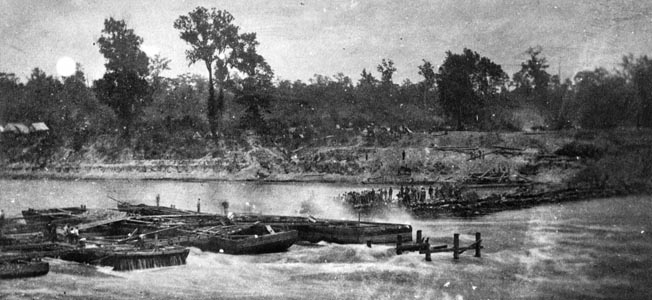

Damming the Red River

When Porter finally reached Alexandria, he was further dismayed to learn that the Red River had fallen to a depth of just over three feet and that the water level was continuing to drop. After sending the shallow draft gunboats below the town, Porter faced the real prospect that his deep-draft ironclads, requiring seven feet of water for passage, would have to be destroyed.

Just when it appeared that Porter might have to abandon or set fire to the largest warships in his fleet, an unlikely source presented a solution to the admiral’s predicament. Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, an engineer from Wisconsin serving on Franklin’s staff, suggested that his troops could build dams along the course of the Red River, sufficiently raising the water level to allow the deep-draft vessels to pass. Porter was willing to try anything. He blurted, “If damming the river could do any good we should have been out of this long ago!”

Bailey set 3,000 men, many of them loggers from New York and Maine, to the task of dam building, and the water level quickly rose, allowing the Union ships to traverse the shallow rapids and shoals. While the dams were being constructed, the Confederates continued to batter Porter’s vessels, setting the transport Emma on fire and capturing City Belle and the 300 soldiers from the 120th Ohio Regiment who were unluckily on board at the time.

By mid-May, Porter was on the move toward Alexandria, and Banks had already pulled out of the city. Taylor grew more frustrated with each passing day. His army was too small to halt the Union retreat. Nevertheless, he was determined to harass Banks to the bitter end. At the town of Mansura on May 16, two lines of battle faced one another, and another artillery duel ensued. When Banks ordered Smith’s battle-hardened veterans to attack, Taylor withdrew. Two days later at Yellow Bayou, Mower proved his worth as a field commander once again as his rear guard turned on the pursuing Rebels and fought them to a standstill. Taylor had shot his bolt. Yellow Bayou was the last Confederate attempt to interfere with the Union retirement.

The Red River Campaign: A Strategic Disaster

While Mower bought time, the vanguard of Banks’s dispirited, depleted, and roughly handled army reached Simsport on the Atchafalaya River. Bailey solved another problem that allowed the Union force to complete its withdrawal to the relative safety of the river’s far bank. He recommended that Porter’s transports be lashed together to create a bridge across the waterway. Men and wagons were soon safely on the other side. When Mower crossed on May 20, the disastrous Red River campaign was over—and with it any aspirations Nathaniel Banks may have had for the White House. Adding to his misery, Banks was met at Simsport by Maj. Gen. Edward R.S. Canby, his new boss, whom Lincoln had recently installed as the commander of the new Military Division of West Mississippi.

The abortive Red River campaign had cost the Union Army 8,000 casualties, 3,700 horses, nine vessels, and 57 artillery pieces. Shreveport remained in Confederate hands, and an upcoming offensive against the port of Mobile was delayed for 10 months. Sherman had to initiate his Atlanta campaign without Smith’s veterans.

Porter’s reputation had suffered as well. After reaching the safety of the Mississippi River, he penned a classic line of understatement: “I am clear of my troubles, and my fleet is safe out in the broad Mississippi. I have had a hard and anxious time of it.” To say the least.

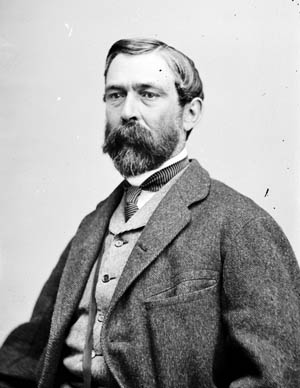

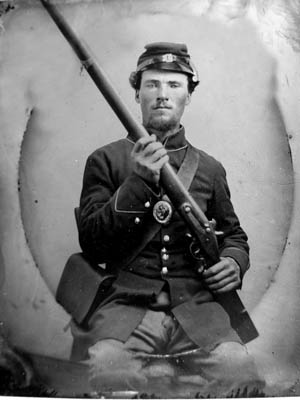

Regarding the unidentified soldier from the Ohio 120th Volunteers

Pictured is Cyrus Willford, born 30 Oct 1842 in Wayne Co Ohio. Cyrus daughter Florence typed up Cyrus’s Reminiscences of the Civil War. The following is a condensed version of Cyrus’s Reminiscences by Greg Watkins in July 2021

Cyrus Willford, Company H 120 Ohio Volunteers entered Oct 9 1962. Went to camp Mansfield Ohio, then Covington Kentucky and put on steamboats for Memphis Tenn. About December 20,1862 joined a large fleet of over 100 boats with several gun boats and landed at Yazoo River Mississippi. They then moved up the Mississippi to White River and Arkansas river. It was cold and snowed. Then down to Youngs point Louisiana. It was most unhealthful and they stayed camped near Grants Ditch around Vicksburg for about 6 weeks and their regiment lost an avg of 6 men per day. About March 1 they moved to Milliken’s Bend. March 20th they started for Hard times landing and had a 40 mile march in 18 hours near bayou Sara. May 1st 1863 they were part of the battles of Port Gibson, Thompson Hill, Magnolia Hills. After these battles they marched every day toward Vicksburg. They were the rear guard during the battle of Champion Hill. They reached the battle line at Vicksburg on May 18th and for 5 days had little to eat and lots of fighting. They participated in the grand charge ordered by General Grant, but were beaten back. The next day Cyrus says he fired 150 rounds towards the Rebel works but had no idea how much damage he did. After 5 days, they went back to Big Black River Bridge to keep Joe Johnson away. They spent 40 days here and served picket duty every other night. When Vicksburg surrendered, Cyrus wrote, “we got a day off”. Then they went after Joe Johnson again and almost had him surrounded, but he slipped away. We then destroyed 15 to 20 miles of railroad tracks, then back to Vicksburg. Then we received order to go to New Orleans. We got to Carrolton and found we could buy bread. While here General Grant came down to inspect the Army. General Grant was a great favorite of the soldiers and the boys cheered him.

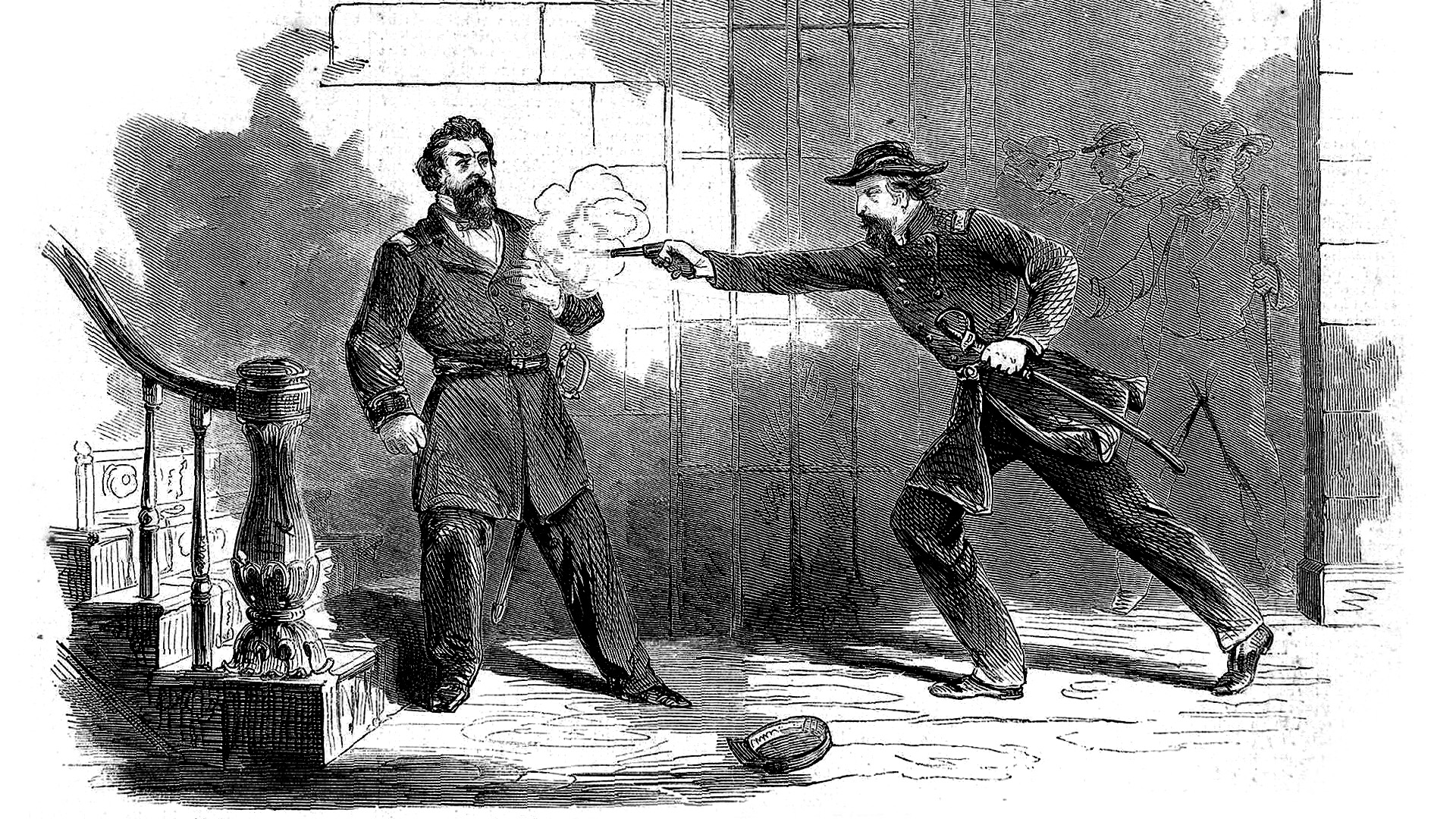

The first time the 13th Corps was defeated was at Mansfield, near Alexandria after General Banks had taken command of us. A division of Rebels was allowed to get between us and the main Army and cut off communication. They captured a gun boat at Snaggy point, then took the old City Bell on May 3, 1864. When the City Belle’s boiler was blown up on Red River near Snaggy Point, Cyrus jumped into the river, but landed on the confederate side of the river. He ran about 5 miles down river hoping to encounter another union transport, but was captured by a man from the 7th Texas Cavalry, Captain Wiggins Company. They were marched 125 miles to Nachitoches and put on a boat to Shreveport, then handed over to a band of Arkansas bushwackers and 4 days later arrived at the confederate prison Camp Ford in Tyler Texas. He remained in the prison for a year and 24 days and dropped to 90 lbs from his normal weight of 165. When he arrived, there were 3 graves in the prison, but a year later there were over 300 graves. Cyrus was mustered out July 4, 1865.

GENEALOGY of Cyrus: parents Daniel Willford and Catherine McFadden Willford

Cyrus married Elizabeth Brubaker and had 4 children, Winfield, Florence, Mildred & Berl.

Florence married AE Wiles and had 8 children, Gerald, Lyle, Cecil, Earl, Harold, Elmo, baby, & Mildred.

Cecil married Dora Decatur and had 2 children, Evertt amd George Elton

George married Thelma Milligan and had two daughters, Lani and Nikki

Lani Married Greg Watkins and had 3 children, Seth, Josh & Leah

Seth married Andrea Levonius and had 5 children, Jack, Allison, Lucy, Emily and Charlie.

Josh Married Erika Palmer and had 8, Zach, Claire, Peter, Sophie, trinity, Megan, Caleb and Justin

Leah married Eric Lammers and had 5, Nicholas, Jude, Isaaic, Gabe and Anna Kate.