By Blaine Taylor

On the evening of May 23, 1945, in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, five men in a British Army jeep were driving down a dark road. Four were guards and the fifth was one of the most important Nazi prisoners of war to have been found in the collapsed Third Reich. The commander of the expedition, a colonel, thought that they were lost, but when he turned to say so, the prisoner set him straight: “You are on the road to Lüneberg.” The prisoner in question was none other than Heinrich Himmler, SS number 168, head of Germany’s dreaded SS and Secret State Police, and his capture, almost accidental, was of great importance to the victorious Allies. Here was the highest ranking Nazi taken alive since the arrest of Hermann Göring on May 9, 1945. What secrets about the Hitler regime might he reveal?

Heinrich Himmler: Head of the SS

Himmler was the third of four Reichsführer-SS (RFSS or National Leader of the SS). The first had been Josef Berchtold and the second Erhard Heiden. After Heiden resigned, Himmler assumed the post on January 6, 1929. He was already a close supporter of Hitler, having taken part in Hitler’s abortive 1923 Beer Hall Putsch that had tried to overthrow the Bavarian government.

Although meek- and frail-looking—certainly nothing like the tall, blond, broad-shouldered, and athletic Aryans pictured on the SS and Wehrmacht recruiting posters—Himmler had an instinct for cunning and self-survival that few others possessed.

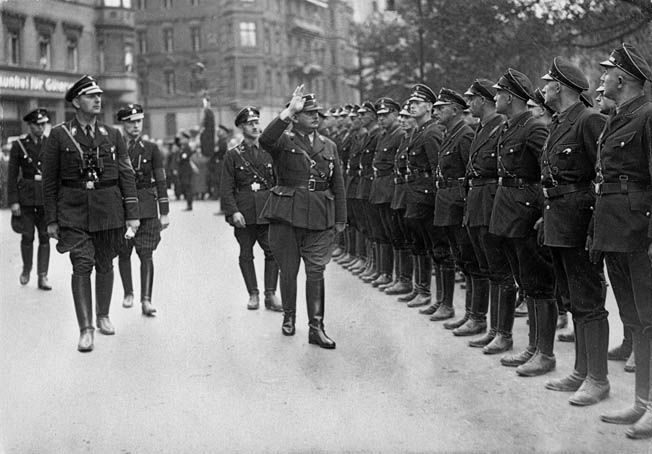

When Hitler appointed Himmler head of the SS, the organization was nothing more than a small, elite bodyguard for the Führer within Ernst Röhm’s much larger Sturmabteilung, or SA, and numbering only 280 men. Through his organizational skills, Himmler had, by 1933, built up the SS to 52,000 men. The uniform had changed, too. Instead of the brown shirts that marked the SA, Himmler went for an all-black costume for his SS (although, at one time, the SS wore brown shirts with black trousers and black kepis). It was Himmler who, along with Göring, persuaded Hitler that Röhm must be eliminated and the brawling SA brought to heel if the Nazi Party were ever to gain the support of the German Army generals and industrialists.

Wewelsburg Castle: “Schoolhouse” of the SS

Himmler had grandiose dreams for his SS. After his first visit on November 3, 1933, he had the SS lease the 17th-century Wewelsburg Castle near Paderborn, a structure that he envisioned being converted into an SS shrine and his official SS “Schoolhouse.”

The castle was built in a triangular form of walls and towers on a pointed limestone spur that had been a Germanic stronghold at the time of the Roman invasion in ad 9. There was in Himmler’s day the famed Knight’s Hall and a trio of towers that were each five stories tall. The North Tower became the SS Valhalla, the fabled “Realm of the Dead.” Moreover, the castle’s crypt contained a dozen pedestals where it was planned that urns containing the ashes of the highest SS leaders of the Third Reich would someday rest. Himmler himself, captivated with the idea of Nordic mythology, fully expected to be interred with great Nazi solemnity in the fortress vault, designed by his hand-picked architect, Hermann Bartels.

Reconstruction performed by slave laborers from a nearby concentration camp began after the SS acquired the castle in 1934, and it was the intention of Himmler to make it the core of an SS city radiating 450 kilometers in all directions.

The castle’s highlight was an Arthurian-like round table for Himmler’s own dozen SS “Knights” that included Reinhard Heydrich; Himmler’s administrative deputy SS General Karl Wolff, who would surrender northern Italy to the Allies in 1945, thus eluding the hangman’s noose; and even their sometime rival, Chief of the German Order (Regular) Police, General Kurt Daluege, who would be hanged by the Czechs as a war criminal after the war.

Himmler’s private study was in the West Tower, and he also had two rooms where he stayed on his frequent visits. During the war, Himmler’s personal weapons collection was hidden within its walls, and thus the legend and mysteries of Wewelsburg persist to this day for treasure hunters.

An SS museum was at the castle, too, as well as a 30,000-volume library of rare books, plus a repository of SS rings. In 1938, Himmler announced that in the future all top SS generals would take their oaths of allegiance at the Wewelsburg each spring. He planned for his 12 department heads to one day be the forerunners of a new pan-European SS State after Nazi Germany won World War II, projected for 1950 by Hitler.

The last major reconstruction project was the North Tower during 1941-1942, but all work ceased in April 1944.

Over the castle’s main entrance there was a Latin inscription that read, “Many would gladly enter, but they will not succeed,” and none did, until Himmler ordered SS General Heinz Macher on March 30, 1945, to destroy the Wewelsburg before the Americans arrived. Much damage was done, but the castle was not completely destroyed.

After the SS withdrawal, the local townspeople looted the castle of 40,000 bottles of wine and champagne, furniture, carpets, art objects, silver utensils, fine china, and linens. Himmler’s personal, top-secret safe was found and blasted open by American GIs, but the contents were never positively identified. It was rumored that the safe contained documents relating to the slain Heydrich. The castle was then occupied by the U.S. Army and is today a tourist attraction.

Growing Up During World War I

Born in Munich on October 17, 1900, the son of a pedantic schoolmaster father, Himmler, whose godfather was Prince Heinrich of Wittelsbach, started keeping a diary at age 10 and in 1914 as a teenager during World War I, he turned it into a war journal: “Aug. 23rd: The Bavarian troops were very brave in the rough battle.” (Read all about the First World War and the conflicts predating the mid-twentieth century inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.)

Heinrich’s eyesight was too poor for him to join the Imperial Navy. While his older brother Gebhard joined the reserves, Heinrich could only stay at home and play with his toy soldiers. In 1915, though, he joined the Jugendwehr (Youth Forces) for field drilling and military lectures in preparation for later joining the Bavarian Army on the Western Front.

Prince Heinrich, 32, died of wounds sustained at the Battle of Verdun, while his namesake was rejected for service by two regiments. Distraught, Heinrich joined the 11th Bavarian Infantry Regiment as an enlisted man on October 16, 1917. Meanwhile, brother Gebhard had been awarded the Iron Cross before the war came to a sudden end in November 1918, followed by a communist revolt in Munich accompanied by considerable economic and political turmoil. His dreams of a military career dashed, Heinrich then decided to study agriculture but fell ill with paratyphoid fever. The following year, recovered, he enrolled as an agricultural student at the University of Munich, where he remained until graduating in 1922.

Entering Into Politics

Caught up in the unrest that was wracking his defeated country, which the socialists had turned into a republic, Himmler joined a nationalist, paramilitary organization known as the Reichskriegsflagge (Imperial War Flag), headed by veteran Ernst Röhm. At some point, Himmler had occasion to hear a young firebrand named Adolf Hitler speak. Mesmerized by Hitler’s oratory and nationalistic fervor, Heinrich joined the Nazi Party in August 1923 and took part in Hitler’s abortive Beer Hall Putsch that November.

Having avoided arrest himself, Himmler threw himself into politics and began speaking at various rallies, espousing anti-government, anticapitalist, and anti-Jewish sentiments. After Hitler was released from prison in December 1924, and Röhm broke away from Hitler, Himmler threw in his lot with the Nazis and received a paid position at the party’s offices in Landshut. His ambition and skill at organizational matters soon caught Hitler’s eye, and Himmler was entrusted with more and more tasks. In 1927, he married Margarete Boden, a nurse seven years his senior. They had one child, a daughter named Gudrun. During the war, he also had a mistress, Hedwig Potthast, with whom he had a son and a daughter.

In 1929, when he wasn’t yet 30, the shy, quiet, methodical, and organized Himmler was named Reichsführer-SS, commanding the Nazis’ national force that protected Hitler and other leaders personally and broke up the meetings of the party’s political opponents.

“Night of the Long Knives”: Destroying the SA

The unobtrusive Heinrich Himmler was on his way to a career unique in 20th-century history. By January 1933, when Hitler was named to the exalted office of chancellor of Germany, Himmler made the SS a haven for those elite young men who scorned the more plebeian brown-shirted SA storm troopers. By war’s end, the Waffen (Armed) SS alone would number 900,000 men in 40 divisions.

Himmler’s first great chance to shine in Hitler’s eyes came in 1934 when the conservative German Army demanded that the chancellor rein in the unruly SA led by Staff Chief Ernst Röhm. The latter’s goal, allegedly, was to replace the regular army with his own men under arms and, as Himmler’s immediate boss, Röhm also stifled the expansion and independence of the SS.

The wily, cunning Himmler and his major deputy, former junior naval officer Reinhard Heydrich, formed a secret political alliance with Hitler’s second man, Hermann Göring, to destroy Röhm and his main SA subordinates. This was duly accomplished via Operation Kolibri (Hummingbird), which led to the murder of Röhm and dozens of his minions between June 30-July2, 1934, known variously in history as the “Blood Purge,” the “Röhm Putsch,” and the “Night of the Long Knives.”

Following this national murder weekend, Nazi Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick correctly warned Hitler, “If you don’t proceed at once against Himmler and his SS as you have against Röhm and his SA, all you will have done is to call in Beelzebub to drive out the devil.” This prophecy came true a decade later during 1944-1945.

Consolidating Power

Himmler was rewarded for his organizational break from the humbled SA. On April 20, 1934, Göring had already turned over to the Himmler-Heydrich team his Secret State Police, the feared Gestapo. The black duo’s next goal was to unite all the various German police forces under their lead, even though neither of them had any police training or experience.

They succeeded on June 18, 1936, when Hitler promoted Himmler to Chief of the German Police. At the Kremlin in August 1939, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin introduced Lavrenti Beria to German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop as, “My Himmler.” Indeed, the two top cops had much in common, including being involved in their respective country’s rocketry programs.

Like his American counterpart, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Himmler was anticommunist by profession, yet it is possible to imagine Himmler accepting an NKVD police post under Stalin after World War II had it been offered. Like Dr. Josef Goebbels and Martin Bormann, Heinrich Himmler was a decidedly leftist Nazi in outlook.

The key, common wellspring behind the characters of all these men was naked power and its practical applications, however, not ideology.

Dr. Felix Kersten: Himmler’s Influential Masseur

On March 10, 1939, just six months before the outbreak of World War II, the high-strung, nervous Himmler underwent the first of a series of manual treatments by Finnish-born masseur Dr. Felix Kersten for his extremely painful stomach cramps. Over time, the doctor-patient relationship developed into one of confidant-mentor between the helpful doctor and his charge.

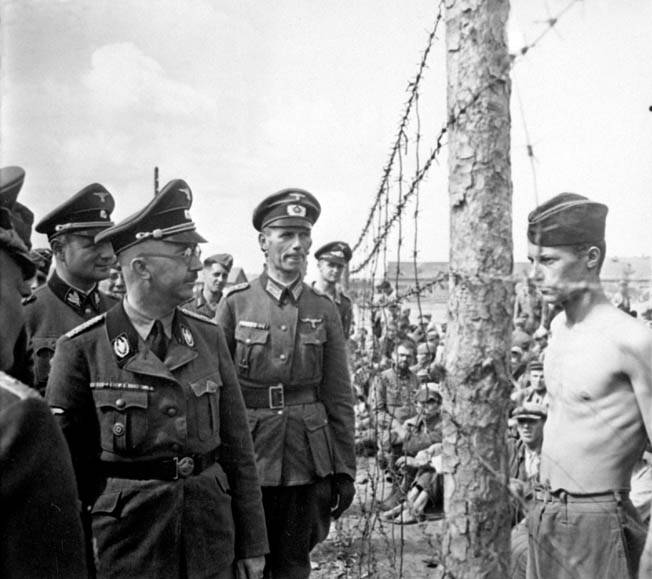

Two years later, in March 1941, the Himmler-Heydrich combine decided to build the first top-secret SS death camps in Poland, occupied by the German Army and SS during the Blitzkrieg campaign of September 1939. Here, they would attempt to systematically murder European Jews, gypsies, and Slavs by gassing.

Simultaneously, in March 1941 was launched a secret SS plan to make occupied Holland an SS state. This would be achieved by deporting the entire Dutch population to the East. As recounted in Dr. Kersten’s 1947 memoirs, this was slated to begin on Hitler’s 52nd birthday, April 20, 1941: “I saw this in secret documents at Himmler’s headquarters on March 1, 1941 … 43 typed sheets … in a yellow folder … signed by Hitler, and countersigned by Himmler … designated as top secret.

“This transfer was to be completed within 13 months and four days … in two installments. The Catholics of southern Holland and the Flemish population of Belgium were to be sent to the eastern states of Greater Germany. The inhabitants of the northern and eastern provinces of Holland and Belgium were to follow. After this, the inhabitants of The Hague, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and Utrecht were to be sent eastward … 8,200,000 … to be moved. Trains, ships, and buses were to be used.…

“The capital of the new Holland would be Lublin [Poland]. The region to be assigned … between the Vistula and Bug Rivers.”

With the future planned for the defeat of the Soviet Union, the Lemberg region would also be given to the Dutch pioneers of the new Nazi East; the Dutch Jews would be eliminated along the way. Dutch Nazi leader Anton Mussert and his followers would be moved to the new Nazi Warthegau (region) in western Poland, with old Holland being established as Himmler’s first fully SS state. The second would follow after the war in Heydrich’s Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and this would entail a second Holocaust against all Slavic peoples.

SS Province Holland would be peopled by new, young SS farmers. The entire coast would be fortified against a possible Allied invasion.

Asserting that he was appalled by this plan, Dr. Kersten, who had a home at The Hague, allegedly convinced Himmler that his nerves would never stand the strain of this massive task added to all his other government portfolios. He reportedly convinced Himmler to ask Hitler to postpone the Dutch deportation until after the war, along with Heydrich’s planned slaughter of the Slavs.

Remarkably, the Führer agreed, and thus the Dutch and Belgians were saved. Some authors believed that the portly Finnish masseur controlled his patient outright because he was able to alleviate his crippling stomach pains and thus gain his confidence while the stricken Himmler lay on the table during his manual healing treatments.

Yet, the fate of others was not so easily altered. On November 11, 1941, Himmler told his startled masseur, “The destruction of the Jews is being actively planned.”

Himmler’s Empire Within the Third Reich

Simultaneously, yet another macabre plan was taking shape in Himmler’s feverish mind. On July 16, 1941, even as the first Holocaust got under way in both Poland and the conquered Soviet Union, Hitler named his faithful Reichsführer-SS to establish and then police the newly occupied former Soviet Ukraine as a German colony, again to be populated by SS farmers following the deportation and murder of all its Jews. This grandiose scheme stretched far into the expected Nazi future, even to the 1960s.

On December 12, 1942, Himmler gave Dr. Kersten the Führer’s personal medical files to read. Kersten, in turn, showed them to Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch, considered Germany’s greatest surgeon, who said that he was “convinced that Hitler was out of his mind.” Himmler dreamed of succeeding Hitler as SS Führer after the war.

What derailed all of this Nazi racial fantasy and empire building was the trio of Soviet Red Army victories in the Battles of Moscow, Stalingrad, and Kursk, reversing the course of the war and putting the Germans on the run. Reacting, the power-hungry Himmler convinced Hitler to appoint him to succeed his own nominal boss, Dr. Wilhelm Frick, as minister of the interior, in August 1943.

By October, Himmler’s empire included almost two million SS troops and 300,000 Gestapo men, along with 30,000 concentration camp Death’s Head guards.

When Himmler attempted to negotiate peace with the Allies in 1945, another bargaining chip with the Allies included the lives of the remaining Jews in those camps. He saw in Dr. Kersten a possibly useful negotiator who had contacts in Sweden, Finland, Holland, and Switzerland, where American OSS chief Allen Dulles was stationed. Indeed, SS General Karl Wolff opened his own negotiations with Dulles in 1945.

“There is Either Victory or the Rope For All of Us”

After the failed Army bomb plot of July 20, 1944, to kill the Führer in Rastenburg, East Prussia, Hitler further turned over to “the faithful Heinrich” command of the German Home or Replacement Army, for the first time placing the SS leader in charge of significant ground forces of the German Army. This was the late Ernst Röhm’s 1934 goal, realized with a vengeance.

In all of his varied posts, Himmler was uniquely placed to realize that the war was lost. Still, he made a final effort to inspire the Nazi leaders to victory. He gave two speeches in October 1943, and four more in 1944, to more than 300 top German leaders. His message was clear: “This is what we have done—and are doing. We are all involved in collective guilt. There is no turning back. There is either victory or the rope for all of us.”

Himmler’s Secret Speech

As it became clear that Nazi Germany was losing the war after disastrous battles on the Eastern Front, Himmler gave a top-secret speech on October 4, 1943, at Posen Castle in western Poland to an elite audience of Third Reich brass. Those present included not only party leaders, but also state ministers and industrialists, and later the supreme commanding officers of the entire German armed forces. The aim of his speech was to reveal the extent of the regime’s murderous activities that precluded any going back to normal modes of conduct. If Germany lost the war, they might all hang as war criminals, so the war must not be lost.

Some excerpts from Himmler’s remarks that day:

“Now, I want you to listen carefully to what I have to say here in this select gathering, but never to mention it to anybody…. I refer––in this closest of circles––to a question which you all, my fellow Party members, have obviously addressed, which, however, has become for me the most difficult question of my life: the Jewish question.

“You all take it as self evident and gratifying that in your Gaus, there are no more Jews. All Germans––apart from a few exceptions––are also clear that we would not have endured the bombing, nor the burdens … of perhaps … the sixth year of the war, if we had this festering plague within the body of our people. The proposition, ‘The Jews must be exterminated’ with its few words, gentlemen, is easily spoken. For him who has to accomplish it, it is the hardest and most difficult of tasks….

“I want to talk to you quite frankly on a very grave matter. Among ourselves, it should be mentioned quite frankly, and yet we will never speak of it publicly…. I mean … the extermination of the Jewish race…. Most of you [and here he gestured to his assembled SS generals] must know what it means when 100 corpses are lying side by side, or 500, or a thousand.

“To have stuck it out—and at the same time, apart from exceptions caused by human weakness—to have remained decent fellows, that is what has made us hard! This is a page of glory in our history which has never been written, and is never to be written…!

“We had to deal with the question: what about the women and children? I am determined in this matter to come to an absolutely clear-cut solution! I would not feel entitled merely to root out the men—well, let’s call a spade a spade; for ‘root out,’ say ‘kill,’ or ‘cause to be killed.’ Well, I just couldn’t risk merely killing the men, and allowing the children to grow up as avengers facing our sons and grandsons!

“We were forced to come to the grim decision that this people must be made to disappear from the face of the earth! To organize this assignment was our most difficult task yet, but we have tackled it, and carried it through, without—I hope, gentlemen, I may say this—without our leaders and their men suffering any damage in their minds and souls.

“The danger was considerable, for there was only a narrow path between … their becoming either heartless ruffians unable any longer to treasure human life, or becoming soft, and suffering nervous breakdowns….

“Before the end of the year, the Jew problem will be settled once and for all! That’s about all I want to say at the moment about the Jew problem. You know all about it now, and you had better keep it to yourselves! Perhaps at some later time—some very much later period—we might consider whether to tell the German people a little more about all this, but I think we had better not!

“It’s us here who have shouldered the responsibility … for action as well as for an idea…and I think we had better take this secret with us into our graves.” He did.

Himmler Takes Command of Army Group Rhine

Taking another secret tack, in November 1944 the now embattled Himmler, thinking about saving his own neck in the event Germany lost the war and wishing to change his horrific image among the Western Allies, ordered that the gassing of the Jews be halted. These orders, however, were often disobeyed by two of his fanatical Austrian SS colleagues, General Dr. Ernst Kaltebrunner (the assassinated Heydrich’s ultimate successor) and Colonel Adolf Eichmann, who wanted the Holocaust to continue.

They were countered as 1945 began by the team of Kaltenbrunner’s own deputy, SS General Walther Schellenberg, and the more moderate Dr. Kersten. They convinced the skittish Reichsführer-SS to initiate secret peace negotiations with the West and to surrender the death and concentration camps intact to advancing Allied troops.

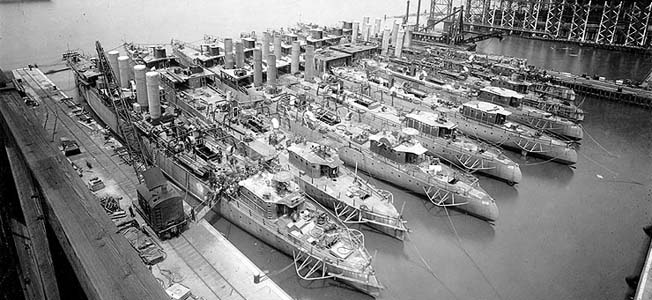

Before that happened, however, on December 10, 1944, as the Western Allied armies neared the German border, Hitler granted would-be soldier Himmler his heart’s dearest wish when he named him military commander of Army Group Rhine on the Upper Rhine River front. As with his prior career as policeman, Himmler’s martial experience was nil aside from his few days in a Bavarian regiment in 1918.

Acting chief of the General Staff Colonel-General Heinz Guderian believed that Himmler’s new post was a sly political maneuver by his chief Nazi rival for power, Hitler’s secretary, Martin Bormann. If Himmler failed, his prestige would fall in Hitler’s eyes, Guderian and Bormann both believed. It was also hoped that Army leader Himmler would now move the Home Army he still commanded closer to the fighting fronts both east and west.

“He’s Never Led a Platoon Across a River!”

Himmler’s first attack, directed from his command Special Train Heinrich in the safety of a tunnel in Germany’s Black Forest, was to retake Strasbourg from the French; the assault failed. Meanwhile, another SS army under Col. Gen. Josef “Sepp” Dietrich helped defeat the Americans in the early phase of the Battle of Bulge in the Ardennes Forest on the German-Belgian border.

As German Army General Siegfried Westphal noted, “He [Himmler] fired off every shell that was sent to him and then simply asked for more.” On January 23, 1945, in the wake of both his Strasbourg debacle and the finally defeated Bulge attack, Hitler shifted Himmler yet again, this time to a third active military field command. This was as commander in chief of Army Group Vistula to defend the Nazi capital city of Berlin against the advancing Red Army from the east.

Wrote Guderian in his postwar memoirs, “He [Himmler] harbored no doubts about his own importance. He believed that he possessed powers of military judgment every bit as good as Hitler’s, and needless to say, far better than those of the generals. ‘You know, my dear colonel-general, I don’t really believe the Russians will attack at all—it’s all an enormous bluff!’”

Guderian later snorted at Himmler’s alleged martial prowess, “He’s never led a platoon across a river!”

In late 1944, Himmler found himself in charge of real soldiers in a desperate battle with the Red Army to stave off the Third Reich’s collapse. One of his officers at Army Group Vistula, Colonel Hans-Georg Eismann, described vividly in his memoir how Army commander Himmler preferred to get his nightly sleep rather than overly trouble himself about his new command’s very real difficulties!

Himmler’s Resignation From Army Group Vistula

In the end, both Bormann and Guderian were proved right. Heinrich Himmler was simply not up to the job militarily. On February 12, 1945, there ensued a furious argument between Guderian and an irate Hitler in the latter’s cavernous office at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

“I want General [Walter] Wenck at Army Group Vistula as chief of staff. Otherwise, there will be no guarantee that the attack will be successful,” Guderian shouted to Hitler as he looked at a sheepish Himmler, adding acidly, “The man can’t do it. How could he do it?” Ironically, trying to curry Himmler’s favor in 1938, Guderian had predicted then that one day Himmler would, indeed, run the entire

German Army.

His own judgment now called into question in front of everyone at the daily military situation conference, Hitler roared back, “The Reichsführer is man enough to lead the attack alone!” not realizing that Himmler and the colonel general had met previously to agree to let Guderian ask Hitler for Himmler’s resignation because he was weighed down by too many offices.

After much shouting, Hitler at last wearily gave in: “Well, Himmler, General Wenck is going to Army Group Vistula tonight to take over as chief of staff.” Turning to Guderian, Hitler smiled wanly, “Herr Colonel General, today the Army General Staff won a battle!” In March 1945, Himmler was replaced altogether as commanding officer of the army group by regular soldier Col. Gen. Gotthard Heinrici.

In the Reich Chancellery Park on March 21, 1945, General Guderian further told the stricken Himmler, “The war can no longer be won.… You must go with me to Hitler and urge him to arrange an armistice.” But Himmler refused: “My dear general, it’s too early for that.” Guderian later asserted, “There was nothing to be done with the man—he was afraid of Hitler.”

When General Heinrici arrived at his new Vistula headquarters to take over, Himmler whisked him aside for a private chat and revealed what he had not told Guderian: “Through a neutral country, I have taken the necessary steps to start negotiations with the West! I’m telling you this in absolute confidence, you understand.” Why Himmler chose an Army general he did not know to confide in no one knows. The crusty old soldier recalled, however, “Himmler was only too happy to leave. He made me want to vomit.”

Contemplating a Fourth Reich

Oddly, just like Göring and even the jailed Rudolph Hess in Britain, Himmler saw himself as the head of a new, postwar, neo-Nazi Fourth Reich; in the case of Himmler, as leader of his own Party of National Union, replacing the Nazis. Recalled his boyhood friend and head of the German Red Cross SS Dr. Karl Gebhardt, hanged as a convicted war criminal by the Allies in 1948, “He believed what he was saying at the moment he said it, and everybody else believed it, too.”

Himmler likewise veered from intimating to Dr. Kersten that Germany’s atomic bomb would be ready if the war could last just a few more months (which he knew was untrue) to regretting that the Reich had not invaded neutral Sweden and Switzerland in 1940 when it had the chance. Meanwhile, the ever more radical Nazi SS peacenik General Walter Schellenberg was pressing Himmler daily to make peace, even to consider shooting or poisoning Hitler if necessary. For his part, the timorous Himmler quaked in his boots at such assertions, and his stomach pains grew worse.

Besides, the Reichsicherheitsdienst (Reich Security Service or RSD) men protecting the Führer reported to Hitler, not to Himmler, and with good reason. Hitler was taking no chances with anyone concerning his personal security, not even with “the faithful Heinrich,” as he touted Himmler.

Himmler’s Secret Meetings to End the War

While SS General Schellenberg arranged two secret meetings with former Swiss President Jean-Marie Musy with Himmler to discuss the release of Jews, another deputy of Himmler, SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Heydrich’s successor as head of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office or RSHA), went to Hitler about it. The Führer immediately issued an order that anyone who released Jews and/or Allied POWs to the Western powers would be shot. Nevertheless, Himmler persisted, but more stealthily than before.

On April 21, 1945, the day after Hitler’s 56th and last birthday, Himmler drove to Dr. Kersten’s home outside Berlin for a top-secret meeting with Swedish Jew Norbert Mazur, a stand in for Hillel Storch of the World Jewish Congress in New York.

Himmler gave Mazur his rationale for the alleged Holocaust thus: “These men helped the Resistance. They fired on our troops from their ghettos, they carry diseases such as typhus. It was to stop epidemics that we sent them to the ovens, and they’re threatening to hang us for this!”

Mazur was incredulous: “You cannot deny that crimes were committed against the prisoners in the concentration camps,” to which Himmler conceded: “Oh, I’ll grant you that there were excesses every once in awhile.” They agreed on one thing: the killing would stop. But the dying continued.

Meeting With Count Bernadotte

There was more. A series of four equally top-secret peace meetings to end the war had also been arranged by Schellenberg for Himmler with the vice president of the Swedish Red Cross, Folke Bernadotte, Count of Wisborg, and a relative of the Swedish royal house. Thus, at the end of his career, Himmler was dealing once more with royalty.

Their first meeting took place on February 12, 1945, at the SS Hohenlychen Hospital, 75 miles north of Berlin. After the war, the count published his detailed remembrance of these negotiations with the dreaded Himmler. “When I suddenly saw [Himmler] before me in the green Waffen SS uniform without any decorations and wearing horn-rimmed spectacles, he looked a typical, unimportant official, and one would certainly have passed him in the street without noticing him.

“He had small, well-shaped, delicate hands, and they were carefully manicured…. He was, to my great surprise, extremely affable. He gave evidence of a sense of humor, tending rather to the macabre. Frequently, he introduced a joke when conversation was threatening to become awkward or heavy. Certainly there was nothing diabolical in his appearance, nor did I observe any of the icy hardness in his expression of which I had heard so much.”

Himmler was, however, the man who ordered the killings of the SA in 1934, launched the Holocaust, and possibly had a hand in the plots to kill Hitler both in 1939 and 1944. Now, in early 1945, Himmler’s name and face were becoming infamous worldwide for the death and concentration camps that were then being overrun and liberated by the Allied armies.

The world gasped in horror as the camp crematoria doors swung open, yet, curiously, Himmler had a blind spot in this regard. He refused to believe that the West would not see in him the logical leader of the new Fourth Reich that would be a bulwark against the advance of Bolshevism—Germany’s and the West’s common enemy. He was now in for a rude awakening, however.

Himmler Offers an Anticommunist Alliance

Count Bernadotte’s terms were that Hitler must give all powers to Himmler, who must in turn remove all Nazi Party officials, cease Werewolf guerrilla activities, and release all Danish and Norwegian prisoners to Sweden via the Swedish Red Cross. The big shock was saved for last: Himmler could not possibly hope for any political role in a future, non-Nazi Germany.

Himmler wanted a message sent to Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower offering a cease-fire in the West and an alliance against the Red Army. In fact, the new U.S. president, Harry S. Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill discussed the Himmler offer by trans-Atlantic telephone on April 25.

Truman rejected it, and Churchill agreed forthwith. Might Winnie, with his well-known anticommunist bias, have considered it without Truman’s prior objection?

On April 29, Reuters news correspondent Paul Scott Rankine in San Francisco got the story from British Information Services head Jack Winocur, who in turn had received it directly from British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, that Himmler had offered a German surrender in the West.

When Hitler learned of the Reuters radio broadcast describing such events, he immediately fired Himmler and ordered him shot on sight, replacing him with Karl Hanke. In a fit of rage, the Führer also had Himmler’s personal liaison officer in the Berlin Führerbunker, SS Cavalry General Hermann Fegelein, shot. Fegelein was the husband of Eva Braun’s younger sister, Gretl.

“They Will Never Find Me”

Hitler committed suicide with wife Eva on April 30, 1945, in the bunker below the Reich Chancellery. His successor as Reich leader, Navy Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, told a downcast Himmler that there was no place for him in his own new government at Flensburg on the German-Danish frontier. Having any connection with the loathed and despised Himmler would be a political and public relations kiss of death.

According to British author Dr. Hugh Thomas, an arrogant Himmler boasted, “They [the Allies] will never find me…. I, for one, shall certainly not commit suicide.” He considered possible escapes to neutral Sweden or, perhaps, even to Franco’s Falangist Spain, just as Belgian Waffen-SS leader Leon Degrelle actually succeeded in doing.

It did not work out that way, though. While Schellenberg was trying to surrender 400,000 German troops in Norway, his former boss and his entourage set off on their final, strange odyssey.

Thus it was that on May 10, 1945, Himmler and 14 disguised SS accomplices began their trek from Flensburg across northern Germany, first by car, and then on foot, sleeping in barns and sometimes outdoors. The group included Hitler’s escort surgeon SS General Karl Brandt; Himmler’s surgeon Dr. Karl Gebhardt; Berlin Gestapo chief Otto Ohlendorf; Himmler chauffeur and bodyguard Josef Kiermaier; General Heinz Macher; adjutant Werner Grothmann; two more escort battalion officers; and seven noncommissioned officers.

Himmler had taken the identity papers belonging to the dead Field Policeman Sergeant Heinrich Hitzinger—whom, ironically, he earlier had had executed for defeatism—shaved off his moustache, and put on a black eye patch.

Noted Dr. Thomas, “All carried papers claiming that they were a newly demobilized detachment of the secret Feldpolizei (Field Police), who were ill, and on their way to Munich under the supervision of Dr. Gebhardt. They’d removed all insigniafrom their uniforms, and in their assorted unmarked jackets and rain coats, they were a memorably conspicuous bunch of cutthroats.”

They hoped their exodus would lead them to safety in the high Bavarian Alps, where they would attempt to be secretly spirited out of the country by Werewolf agents––the clandestine Odessa operation. Instead, on May 18 the group reached Bremervörde. There they mingled with a crowd of Germans heading west on a bridge over the Oste River. Unfortunately for them, at the bridge was a British Army security roadblock manned by members of the Black Watch Regiment. Their papers did not seem to be in order and, since the German Field Police had been marked as a suspect group by the Allied intelligence services, the small group was taken into custody as prisoners of war.

Suicide in British Custody

On the morning of May 23, the group was taken to a civil internment camp at Westertimke. Himmler and two others were separated from the group and taken that evening to the 031 Civil Interrogation Camp at Barnstedt. After two days of interrogation by the British, the fugitive former Reichsführer-SS said, “You don’t seem to realize who I am.”

“No,” said the sergeant.

“I am Reich Minister Heinrich Himmler, Reich Führer of the SS!” he boasted proudly.

“Oh, yeah?” said the sergeant. “Well, I’m Winston Churchill!”

“I am Himmler, you fool!” the prisoner shouted angrily. “I demand to be taken to General Eisenhower or Montgomery!”

The sergeant sent for Captain Sylvester, the camp commandant. Himmler repeated his claim, and Sylvester telephoned Colonel Michael Murphy, Chief Intelligence Officer at Second British Army Headquarters at Lüneburg. Intrigued that one of the most-wanted war criminals in all of Nazi Germany might actually be in British custody, Murphy told Sylvester that he would be there shortly.

Murphy arrived at Barnstedt at 9:45 pm to take charge of Himmler. The former Reichsführer, who had been stripped of his clothing, refused to put on a British uniform for the trip and so was given a blanket to wrap around him, then was put in a jeep with Murphy and an armed escort and driven the 10 miles to British headquarters at Lüneburg, arriving there at 10:45.

They pulled up in front of 31a Uelzenerstrasse, a red brick villa that British intelligence officers were using as an interrogation center. Although C.J. Wells, a British doctor, examined him carefully, he somehow missed the tiny vial of cyanide of potassium that was concealed in Himmler’s mouth. The questioning began anew, and Himmler repeated his claim to be the Reichsführer-SS and again demanded to see one of the Allies’ top generals. He even wrote out his signature to prove his real identity.

Even as a British POW, Himmler still believed it impossible that the Western Allies would not see the eminent sensibility of using his gifts as a secret policeman par excellence in their future rule of postwar Europe.

During questioning, Dr. Wells again became suspicious and ordered Himmler to open his mouth to be searched one more time. As Wells stuck his fingers in Himmler’s mouth, the German clamped down on the doctor’s fingers, worked the vial out of its hiding place with his tongue, and then bit down hard on the fragile glass. After briefly going into convulsions, he slumped to the floor. The officers quickly grabbed a bucket of water and, holding Himmler by the ankles, repeatedly dunked his head into the water, trying to dilute the poison.

“We immediately upended the old bastard,” recalled one eyewitness, “and got his mouth into the bowl of water, which was there to wash the poison out. There were terrible groans and grunts coming from the swine.… It was a losing battle, and the evil thing breathed his last.”

At 11:14 pm on May 23, 1945, Himmler, wearing only a British Army shirt and socks, was declared dead. With an Army blanket around his shoulders, someone placed a pair of eyeglasses on his face that made the corpse look more like Himmler. On May 26, after an autopsy, Himmler was buried by Major Norman Whittaker, Command Sergeant Major Edwin Austen, and Sergeants Ray Weston and Bill Ottery in a secret grave somewhere on the Lüneburg Heath, its exact location kept secret to this day. There was no funeral service of any kind.

“Utterly Mediocre”

As for the other players in the grim SS drama, Kaltenbrunner was hanged as a convicted war criminal at Nuremberg on October 16, 1946, where Schellenberg, too, was tried and sentenced, then pardoned in 1950. Schellenberg died in Italy of stomach cancer on March 31, 1952. Count Bernadotte, serving as a United Nations mediator in the Middle East, was assassinated in 1948 by Jewish Zionist terrorists who believed that he stood in the way of their planned State of Israel.

Arch-criminal Himmler, whom German historian Joachim Fest characterized as being “utterly mediocre … a romantically eccentric petty bourgeois … who attained exceptional power and hence found himself in a position to put his idiocies into bloody practice,” still lies in his unmarked grave, gone but not forgotten.

Beria was the Allied Himmler, according to Stalin.