By Mike Phifer

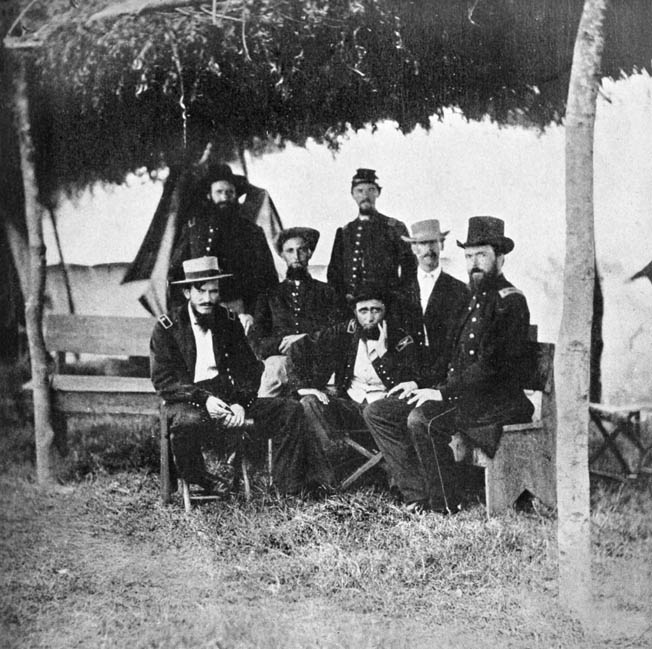

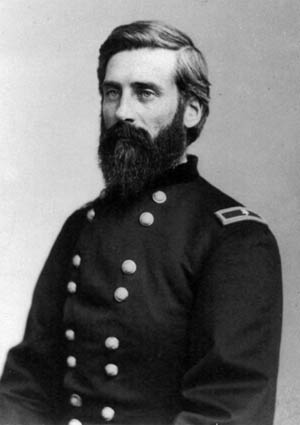

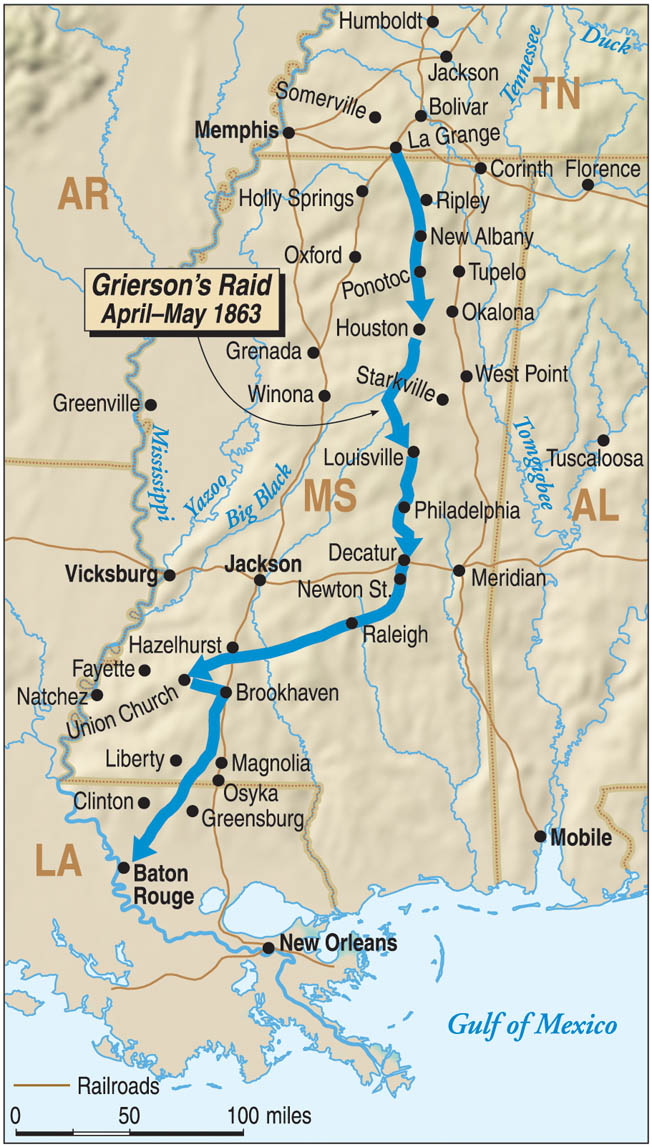

Union Colonel Benjamin Grierson stuck his left foot into the stirrup and swung up into the saddle. Orders were quickly given, and soon a column of 1,700 blue-jacketed troopers of Grierson’s 1st Brigade, along with a battery of artillery, trampled southeast from La Grange, Tennessee, in the early dawn of April 17, 1863. The cavalrymen were traveling light, packing only five days’ rations to last them 10 days, oats in the nosebag for their mounts, and 40 rounds of ammunition for their carbines and revolvers.

The blue column snaked into the pine-clad hills of northern Mississippi. Most of the men thought they were headed on a scouting mission to Columbus to smash up the railroads there. They were wrong. Only the 36-year-old Grierson and his aide, Lieutenant Samuel Woodson, knew the true objective of the raid. It was much deeper into enemy territory—and much riskier.

The key Confederate port of Vicksburg, on the east bank of the Mississippi River, had withstood numerous Union attempts to capture it since late 1862. Finally, in early 1863, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant decided on a bold plan to march a good portion of the Army of the Tennessee down the west bank of the river past Vicksburg while naval support slipped past the port’s defiant batteries. Then Grant would move his troops across the mighty river and secure a beachhead before investing Vicksburg from the south. To help keep the Rebels distracted from the beachhead, various diversions were needed.

Besides feints north of Vicksburg, a cavalry raid south of Vicksburg was planned to disrupt the railroads, especially the Southern Railroad of Mississippi, the main supply line into the city, and tie up Confederate forces there. Grant wanted Grierson to lead the raid, writing to Maj. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut, commander of XVI Corps, in Memphis in mid-February: “It seems to me that Grierson, with about five hundred picked men, might succeed in making his way south, and cut the railroad east of Jackson, Miss. The undertaking would be a hazardous one, but it would pay well if carried out.”

Grierson’s Raiders

The raid suited Grierson, who in December had taken command of the 1st Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, XVI Corps. The brigade consisted of the 6th Illinois, 7th Illinois, and 2nd Iowa Cavalry. Grierson did much of the planning of the raid, although he was aided by his superiors, Generals Hurlbut and William Sooy Smith, who commanded the La Grange camp. Although Grant had initially suggested that Grierson should take 500 men, this force was increased to 1,700 troopers—Grierson’s whole brigade plus Battery K of the 1st Illinois Artillery, which sported six light-caliber Woodruff guns.

Although Grant wanted the Southern Railroad cut somewhere between Meridian and Jackson before his army crossed the Mississippi, it was decided that more had to be done than just tear up tracks. To distract the Confederates, the town of Newton Station would be the primary target. There the tracks of the Southern Railroad could be wrecked and the railroad depot burned. Newton Station also offered the opportunity of wrecking tracks on the nearby Gulf & Ohio Railroad, which ran north and south.

To give Grierson’s raiders a better chance of success, two other short raids were to be launched at the same time by the Army of the Tennessee into northern Mississippi. Meanwhile, the Army of the Cumberland was planning a raid through northern Alabama and Georgia, which was also timed to coincide with Grierson’s raid.

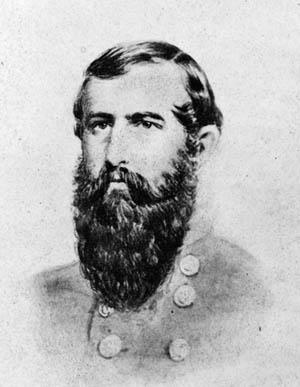

Commanding the Confederate Department of Mississippi and Eastern Louisiana was Lt. Gen. John Pemberton, who had about 50,000 men. The strongest force was kept at or near Vicksburg, while two cavalry units under the command of Colonel William Wirt Adams were stationed at Port Gibson. Another large force was positioned at Port Hudson under Brig. Gen. Franklin Gardner. Other forces under Maj. Gen. William Loring and Brig. Gen. John Chalmers were in northern Mississippi, while Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles, in Columbus, was responsible for defending northeast Mississippi. Troops were also stationed at such places as Jackson and Grand Gulf, supported by local militias and state troops spread throughout the department.

Grierson, a music teacher before the war, was visiting his family in Jacksonville, Illinois, when a telegram arrived from Hurlbut telling him to return immediately. The raid was on. Grierson arrived back at La Grange in the early hours of April 17, and Smith gave him some last-minute instructions to cut the Southern Railroad and, if practicable, the Mississippi Central and the Mobile & Ohio Railroads as well. After talking with Smith, Grierson rejoined his brigade. Colonel Edward Hatch, commander of the 2nd Iowa, had the brigade ready to go.

First Skirmishes

Riding south, Grierson’s force was soon split, with the 6th Illinois advancing on a western road and the 7th Illinois and 2nd Iowa on a parallel road to the east. Grierson’s horse soldiers covered 30 miles the first day, stopping for the night four miles northwest of the town of Ripley at a plantation owned by a Doctor Ellis. After capturing some Confederates nearby, the troopers settled down for the night, lighting fires and enjoying fare taken from Ellis’s smokehouses—something they would do at many local plantations in the coming days.

By 7 am, the raiders were mounted and moving toward Ripley with the 7th Illinois under Colonel Edward Prince leading the way. Once at Ripley, Grierson ordered Hatch to make a feint with the 2nd Iowa east toward the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, while the rest of the brigade headed south toward New Albany.

Four miles south of Ripley, gunshots suddenly rang out as a detachment of eight Confederate horse soldiers fired at the advance party of the 7th Illinois. The blue-jacketed troopers charged after the fleeing Rebels but soon reined up their mounts. Nobody was hurt in the exchange, and the advance party, fearing an ambush, decided to wait for Prince and the rest of the regiment to join them. Concerned that a strong Rebel force might be lurking along the Tallahatchie River, 12 miles away, Prince ordered Major John Graham to take to his 1st Battalion and ride hard for the bridge at New Albany.

Hatch and his 2nd Iowa horsemen, meanwhile, turned south toward Molino. Scouts from Colonel J.F. Smith’s 1st Mississippi Regiment, a state guard unit based out of Chesterville, soon spotted the column of Federals. Having only one company on hand to face the enemy cavalry, Smith dispatched a messenger to Chesterville while he attempted to slow down the Union advance.

Hatch was not the only Federal raider then skirmishing with the Confederates. Graham and his hard-riding battalion encountered Rebel pickets as they thundered toward the bridge over the Tallahatchie. While some of the pickets fired at the Federals, others attempted to tear up planks and torch the bridge. Graham’s cavalry was coming too fast for the pickets to do much damage, and they scrambled for their horses and attempted to escape. Four of them weren’t fast enough and were captured along with the bridge. Graham ordered his men to dismount, repair the planks, and prepare to defend the bridge. As it turned out, it was unnecessary; Grierson and the main column forded the river three miles upstream.

Taking Pontotoc

By late afternoon the two Illinois regiments had reunited at New Albany and pushed five miles southeast under a darkening sky. Grierson was hoping that Hatch would rejoin him, but the Iowans halted for the night after crossing the upper branches of the Tallahatchie. The Illinois troopers camped for the night at another local plantation, enjoying food from its smokehouses and finding a herd of horses and mules hidden in the woods. The four prisoners taken at the bridge, meanwhile, starting talking. Two of them were state troopers, while the other two belonged to Lt. Col. Clark Barteau’s 2nd Tennessee Cavalry, which was part of Ruggles’ command, stationed less than 20 miles away with 400 or 500 regulars and as many state troopers. The prisoners also revealed that a few miles to the northwest a detachment of the 18th Mississippi Cavalry under Major Alexander Chalmers was camped at King’s Bridge.

Torrents of rain pounded down during the night but slackened a little by first light. Grierson hoped to further confuse any pursuit by dispersing Rebel cavalry camps in the vicinity. Two companies from the 7th Illinois under Captain George Trafton slopped north on the muddy road to New Albany. There they found a body of state troops. Trafton’s wet and muddy men charged forward, guns blazing in the rain. The Confederates scattered, but not before eight were killed or wounded.

Two other companies from the 7th Illinois rode out for King’s Bridge to disperse the Rebels, but they found only hastily deserted lean-tos, tents, unrolled bedding, and smoldering cookfires. The final detachment sent out by Grierson, also consisting of two companies, rode east in an attempt to make contact with Hatch and give him orders to make a demonstration toward Chesterville. They were also to look for a hidden herd of horses reported by the prisoners to be concealed in the woods a few miles away. The raiders needed fresh horses, since the fast-moving raid quickly exhausted their mounts.

The troopers managed to find only a few horses, but they did make contact with Hatch’s advance guard and passed along Grierson’s orders to Hatch before riding back to rejoin the rest of their regiment. After breakfast, the 6th Illinois mounted up and headed toward Pontotoc, followed by the returning six companies of the 7th Illinois.

Around 4 pm, the 6th Illinois neared Pontotoc. Grierson expected a fight and ordered the advance troops to ride toward town in an attempt to determine the defenders’ strength. Some citizens and state troopers fired on the advance guard but soon fled upon seeing the whole Federal regiment. A lone defiant Rebel, however, remained and continued to fire on the bluejackets until he was killed. The town was soon in Grierson’s hands, and a wagonload of ammunition was promptly destroyed. While the 6th moved out, a search party from the 7th discovered and destroyed 500 bushels of salt hidden in an old mill.

Quinine Brigade

After making a feint toward Chesterville, Hatch’s Iowans, slowed by state troop skirmishers, finally rejoined Grierson. That evening the raiders encamped five miles south of Pontotoc at two plantations. On the morning of the 20th, bugle calls awoke the troopers. After boiling some coffee and packing their gear, the soldiers assembled with their mounts for inspection. Men and horses thought unfit to continue the raid were shunted aside to form a special detachment. These 175 men, nicknamed “the Quinine Brigade” by the rest of the brigade, were put under the command of Major Hiram Love of the 2nd Iowa. Grierson sent the men back to La Grange, along with several prisoners and a number of spare horses and mules. Accompanying them was one of the Woodruff guns.

At 3 am, the Quinine Brigade, formed into columns of four, rode out of camp for Pontotoc. Grierson hoped they would obliterate his tracks and deceive the Rebels into believing the whole brigade had turned back. Meanwhile, the rest of the brigade was soon back in the saddle and continuing south toward the town of Houston.

Barteau’s combined force of Confederate regular cavalry and state troopers was also in the saddle and attempting to pick up the trail of the Union raiders, who they had expected to attack them the day before at Chesterville. After receiving word the enemy had passed through Pontotoc, Barteau rode through the night for Okolona Station on the Gulf & Ohio Railroad, believing this was the raiders’ true objective. But Barteau failed to find any fresh tracks indicating that mounted forces had passed by. He headed for Pontotoc, which his advance scouts reached at noon.

Barteau quickly learned that the Federals had passed through the area hours before and were headed west for Oxford. Barteau send a detachment to follow the Quinine Brigade, which he figured was a diversionary force. After the scouts returned with news that the small force of Federal cavalry had turned north, Barteau ordered his men to follow the main force of enemy raiders. At nightfall they camped a mile and a half north of Houston to give their worn-out horses and men a much-needed rest.

Barteau’s Ambush

By this time Grierson had passed Houston and was camped 12 miles south of the town at another local plantation. That night Grierson met with his regimental commanders and other key officers to discuss decoying Rebel pursuit. He ordered Hatch to take the 2nd Iowa and strike for the Gulf & Ohio Railroad from West Point as far south as Macon if possible. Then, if practicable, they were to hit Columbus, destroying the government works there and striking the railroad south of Okolona before returning to La Grange.

At 7 am on the 21st, Grierson’s brigade broke camp and headed southeast on another rainy day. After the column of bluejackets passed through Clear Springs, Hatch halted his regiment. “This patrol,” wrote Sergeant Lyman Pierce, “returned in columns of fours, thus obliterating all the outward bound tracks. The cannon was turned in the road in four different places, thus making their tracks correspond with the four artillery pieces which Grierson had with the expedition. The object of this was to deceive the rebels, who were following us, into the belief that the entire column had taken the Columbus road.”

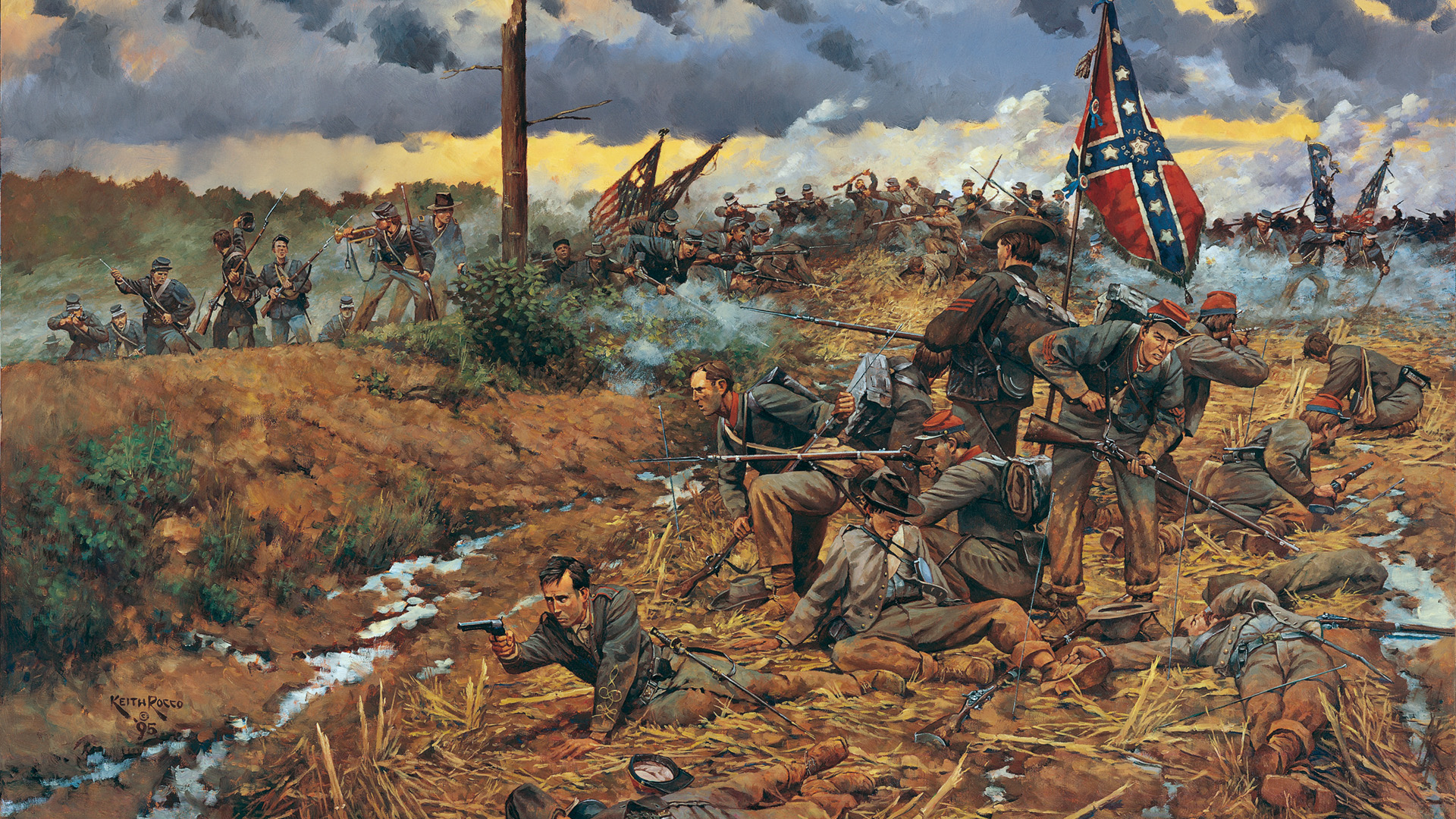

The deception worked. Barteau’s scouts found the tracks and assumed the main column of Union cavalry had doubled back and was riding east for the Gulf & Ohio Railroad at Columbus. Barteau sent his men galloping eastward along the muddy road after the enemy, which he soon overtook at Pala Alto. Around noon, as the rain started to lighten, Barteau made contact with Hatch’s command, which was just preparing to mount up after halting for lunch. Shots rang out as Hatch’s rear guard was overrun by the Confederates. Barteau’s men then charged toward the main body of Federals.

Hatch, hearing the gunshots, ordered his men to continue into a hedged lane and dismount. Taking cover along the brush and trees that bordered the lane, the Iowans, armed with sporting Colt revolving rifles, opened up on the Rebels. Barteau, sensing he had the Federals trapped, halted the charge and sent four companies of Tennesseans to take up positions at the far end of the lane while he attacked the enemy with the rest of his command.

Hatch Holds the Confederates Back

Hatch’s men had good cover, and for two hours they held off the Rebels. Then Barteau shifted his men, putting his green Mississippi state troops in Hatch’s front, where they had the cover of a church and some trees. There they were to hold their fire until the Federals were “close enough to make it destructive and deadly.” The 2nd Tennessee, meanwhile, formed to attack up the lane and hit the enemy rear. Before the Confederates could attack, Hatch struck first.

The lone Woodruff gun opened up on the Mississippi troops while the Iowa cavalrymen hit the Mississippians hard, causing them to retreat in disorder. Hatch’s men pushed the Confederates three miles toward the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Barteau and his Tennesseans, meanwhile, rode hard to place themselves in a position between the Yankees and the railroad tracks. They dug in for the night and waited for reinforcements, intending to continue the battle the next morning.

Hatch had other ideas. He led his men northward through a large swamp, guided by an African American scout. After crossing a river with considerable difficulty during the night, Hatch’s raiders struck Okolona near sunset on the 22nd, finding it abandoned and torching 30 barracks full of cotton. Barteau, reinforced by Lt. Col. James Cunningham and his 2nd Alabama Cavalry, rode after Hatch.

Pushing north again on the 23rd through more swamps, Hatch’s men found horses and mules hidden by their owners. Barteau continued to dog the raiders, who were burning bridges as they withdrew north. On April 24, nearing Birmingham, Hatch divided his force, sending six companies to the east while the rest of his command, along with 31 prisoners and 200 escaped slaves who were helping to drive the 600 captured horses and mules, proceeded into town.

Making a forced march, Barteau finally caught up with Hatch’s rear guard, which put its Colt revolving rifles to good use stopping three charges before being forced back on the rest of Hatch’s command, which repulsed the Confederate attack and fell back across a bridge over Camp Creek. The bridge was then torched, ending the skirmish after it had cost the Confederates 30 men and exhausted their ammunition. Hatch returned safely to La Grange a couple of days later, having lost only 10 men himself.

The Butternut Guerrillas

Grierson, meanwhile, was continuing to push south. Ahead of the column of horsemen now rode a group of scouts led by a Canadian quartermaster sergeant named Richard Surby. According to Surby, he approached his superior, Lt. Col. William Blackburn, executive officer of the 7th Illinois, with the idea of “having some scouts in the advance dressed in citizens clothes.” Blackburn discussed the idea with Grierson, who approved it and gave Surby permission to form his scouts. Eight men from the 7th Illinois were dressed as irregular Confederates. The scouts, nicknamed “the Butternut Guerrillas,” would prove quite useful to Grierson.

Passing through Starkville on April 21, the raiders seized Confederate mail and destroyed supplies. Grierson was disturbed to learn that the townspeople knew the raiders were coming. As a violent storm flashed and crashed overhead, the bluejackets pushed south from Starkville through swamps where horses struggled through belly-deep mud and water. Finding some high ground, the raiders stopped for the night. Graham’s 1st Battalion, however, got little rest. Grierson earlier had received information from a slave about a nearby tannery, and he sent Graham’s force to destroy it.

Concerned that the Confederates had been telegraphed of his force passing through Starkville, Grierson decided to send out another diversionary force, Company B of the 7th Illinois. Commanded by Captain Henry Forbes, the company was given the dangerous mission of riding fast to Macon and pulling up the Mobile & Ohio Railroad tracks, ripping down telegraph wires, and drawing as much Confederate attention as it could.

Separating from the main column, Forbes and Company B rode east for 30 miles. That evening Forbes halted his company at a plantation three miles from Macon. Around 9 pm, pickets captured a Confederate scout who revealed that a trainload of infantry was expected to arrive that night. Forbes’ own scouts soon heard the whistle of an engine, leading the captain to believe that enemy reinforcements were arriving in town. Taking Macon was now out of the question. Forbes felt they had done what they came for; he would later report, “We kept all eyes on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.”

He was right to do so—Pemberton knew now that 2,000 Union cavalrymen were raiding deep into his district, but he believed the Mobile & Ohio was their main objective. He sent Loring to Meridian to take command of all troops in the area and run down the enemy raiders. Troops went quickly by rail to Macon, where Pemberton had received reports of a large enemy force approaching. This was Forbes’ company.

Grierson, after a rugged journey through deep mud and water, was nearing Louisville. He ordered Major Mathew Starr to ride ahead with a battalion of the 6th Illinois and secure the town. When Starr’s men galloped into Louisville they found the streets empty and the buildings closed—the townspeople had been warned of the Yankees’ approach. After the main column passed through town, Grierson left Graham’s force behind for an hour to make sure no one left with news of the raiders. The column then pushed on through more swamps before camping around midnight at another plantation. It had been a rugged 50-mile journey, but their objective now lay only 40 miles away.

On the morning of April 23, the Butternut Guerrillas galloped ahead of the main column with orders to capture a key bridge over the flooded Pearl River. A couple of miles from the bridge the scouts chanced upon an elderly man who told them the bridge was held by a guard of five men, including his son, and that they had ripped up some planks in the center of the bridge and placed incendiaries in the openings. The old man reluctantly agreed to help after he was warned that the raiders would destroy his property if the bridge was damaged.

The old man talked his son and the guards into galloping away, leaving the bridge in the scouts’ hands. After replacing the missing planks, Surby left one scout to wait for the main column and led the rest of his men after the fleeing guards, who he worried would spread word of the Union advance. As he neared Philadelphia, Surby spotted armed men drawn up in a line across the road. He immediately requested that an additional 10 men be sent up to reinforce the Butternut Guerrillas. When Surby saw the help coming, he led his scouts forward, revolvers blazing, and stampeded the Rebels. The town was quickly in Federal hands.

Seizing the Trains

The muddy blue column of cavalry continued to push south. After a brief rest, Grierson had his men riding through the night. He sent Blackburn and 200 men of the 7th Illinois ahead with orders to capture Decatur and scout the ultimate target of the raid, Newton Station. Blackburn easily secured Decatur and halted six miles outside Newton Station. Grierson then ordered Surby and two scouts to ride into town to reconnoiter. Riding to within half a mile of town, Surby halted on an elevated position to have a better look at Newton Station. No enemy camp or pickets were visible, and Surby could only see a few people moving around a large building that he took to be a military hospital. Pushing closer to town, Surby and his two scouts stopped at a house on the edge of town, where he learned that two trains were due to arrive shortly.

Not wasting any time, Surby sent one of his scouts back to inform Blackburn and then hurried into town with his other scout to capture the telegraph station, which he found closed. Convalescents soon began to pour out of the hospital upon seeing the two scouts. Surby pulled his revolver and told them to remain inside.

Blackburn and his men thundered into town none too soon as a freight train puffing black smoke approached a mile east of town. Most of the blue raiders dismounted, hid their horses, and took cover; pickets moved to secure the different approaches to town. The locomotive, pulling 25 freight cars loaded with ordnance and commissary supplies for Vicksburg, rolled into the station. Blackburn gave a signal, and troopers came out from hiding and seized the train, then quickly hid again as a second train neared town.

The combined freight and passenger train soon slowed down by the depot. Surby climbed aboard the locomotive and pointed his revolver at the engineer, telling him that if he reversed the engine Surby would put a ball through him. The troopers rushed from their hiding place and seized the train’s 13 cars. Four of the cars carried ammunition and arms, while six had commissary stores on them and the remaining two contained personal belongings of people leaving Vicksburg.

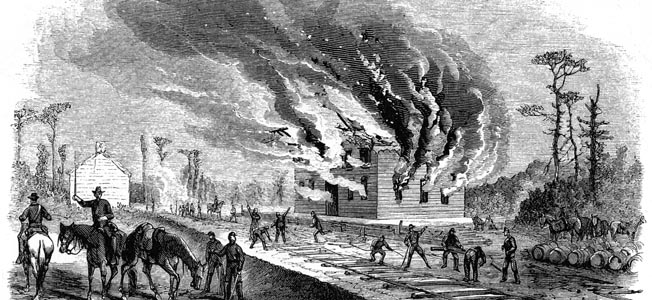

Since both trains carried explosives and loaded shells aboard them, Blackburn had them moved away from the hospital after the civilians’ goods were removed from the two boxcars. They were then set on fire, and the shells and ammunition began to explode. Grierson, who was nearing town, heard the ammunition exploding and charged into Newton with his men, believing Blackburn was under attack. Grierson was relieved to learn the true state of events. Now serious destruction got underway.

Destruction of Newton Station

The Federal cavalry commander ordered Starr to take two battalions of the 6th Illinois east of town to torch bridges and trestles, cut down telegraph poles, and destroy the lines. Captain Joseph Herring was ordered west of town with a battalion of the 7th Illinois to do the same thing. More destruction took place in town, where a warehouse containing 500 arms and a large number of uniforms was set on fire. Railroad rails were pulled up and thrown on fires of burning crossties and then twisted. The two locomotives exploded.

By 2 pm, the destruction was complete, and Grierson headed south again, knowing the Confederates were looking for him to the north. Before leaving the burning and smoking destruction at Newton Station, Grierson and his officers asked some of the paroled Confederate officers taken at the hospital about various roads to the east, hoping to confuse pursuers.

After a three-hour rest five miles south of Newton Station, the raiders pushed on to Garlandville around dusk. Grierson would later write, “We found the citizens, many of them venerable with age, armed with shot-guns and organized to resist our approach.” A cavalry charge scattered them, but not before they got off a volley that severely wounded a trooper. The militia was disarmed and released. Grierson reported that the militiamen were apologetic, “acknowledging their mistake, and declared that they had been grossly deceived as to our real character. One volunteered his services as a guide and upon leaving us declared that hereafter his prayers should be for the Union Army.”

The Federal column pushed southwest again, the exhausted men slumping in the saddles. Some actually fell asleep as they rode, having not slept more than five hours in the last 72. Finally, they stopped for the night around midnight at a plantation belonging to a Doctor Mackadora, 50 miles from Newton and a couple of miles west of Montrose.

Sighted By Confederate Cavalry

By 8 am on April 25, the troopers were back in the saddle again, riding west. To get his men safely out of Rebel territory, Grierson intended to head for Grand Gulf along the Mississippi, where he knew Grant was intending to land his army. By this time, hearing of the strike on Newton Station, Pemberton tardily grew concerned over the rail line to Vicksburg and mobilized more units, including Adams’ cavalry.

After making only five miles, the Federal column held up at a plantation, resting until 2 pm, while parties were sent out to find fresh horses hidden in the swamps and woods. They continued on, stopping at another plantation for the night. Grierson ordered one of Surby’s scouts, Sam Nelson, to create a diversion by riding north to Forest Station on the Southern Railroad and cutting the telegraph line. If possible, Nelson was to torch bridges and trestles as well.

Nelson, however, would not complete his mission; he ran into a Confederate cavalry detachment under Captain R.C. Love. The quick-thinking Nelson told Love that he was a paroled Confederate and claimed the Yankees numbered 1,800 men and were headed east toward the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Satisfied with his answers, Love let Nelson go. The raider raced back to warn Grierson, knowing that once the Rebel cavalry reached the main road and saw the Federal cavalry column’s tracks, they would determine their true direction.

Forbes’ Company B, meanwhile, reached Newton Station, where they learned from prisoners of the Federals intention to head east. It was rumored that that Federals were at the town of Enterprise, where Forbes was now determined to go. Sometime around 1 pm he neared the town only to find it strongly held by the Confederates. In a bold move, Forbes approached the town under a flag of truce and met with Colonel Edwin Goodwin, commander of the 35th Alabama Infantry, demanding the surrender of the town on behalf of Grierson. Goodwin asked for an hour to consider the surrender offer, to which Forbes agreed. Forbes did not wait around to hear Goodwin’s answer, galloping west as soon as his back was turned.

Grierson was asleep when Nelson arrived in the early morning of April 26 with news of encountering the Rebel cavalry. The camp was soon a bustle of activity as the Federals prepared to pull out; by 6 am they were riding west, burning bridges behind them. By nightfall they passed through Westville and stopped to rest two miles to the west at a plantation. With them they had the Smith County sheriff, who had been captured by Surby’s scouts.

Crossing the Pearl River

The raiders made 40 miles with 60 more to go before reaching Grand Gulf. Two major rivers lay in their way, and Grierson wanted crossings over them seized and held. He directed the 7th Illinois to seize a bridge over the Strong River, leaving a detachment to hold it. Two other battalions, under Prince, rode on to capture a ferry over the Pearl River that was vital to the Yankees’ escape. By the early morning of the 27th, Prince had reached the river’s edge only to find the ferry on other side of it.

The ferry came back across the river, its handlers mistaking the Federals for Confederate cavalry. Twenty-four mud-splashed troopers and their mounts boarded the ferry and were taken across the river. Prince had ordered them to capture the Confederate guards on the far side only they discovered there were none. Grierson soon arrived, but it would take eight hours to get his whole command across the river. Meanwhile, Prince and the two battalions under his command, with the Butternut Guerrillas in the advance, headed toward Hazlehurst, where the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad passed through town. Prince sent in two of the Butternut Guerrillas to send a telegram to Pemberton telling him that the Yankees had reached the Pearl River but found the ferry destroyed and were heading northeast.

The message was duly sent by the telegraph operator, but as the two scouts headed out onto the muddy street they were spotted by the Smith County sheriff, who had escaped during the night. The scouts jumped onto their horses and spurred out of town, rejoining the other scouts a mile to the east. Surby sent back word to Prince about what had happened, then charged back into Hazlehurst, finding the streets deserted.

With rain beginning to pound down yet again, the scouts learned that a train was coming. The rest of Prince’s command soon arrived and set up an ambush for the southbound train. Spotting the bluejackets as he rolled into town, the engineer put the engine in reverse and steamed back out of Hazlehurst. Despite this setback, the raiders tore up tracks and torched a good number of boxcars full of commissary stores, ammunition, and shells. An explosion accidentally set some of the buildings on fire, which the Federal troopers tried to help extinguish.

The rest of the brigade soon joined Prince, and they were heading west again by 7 pm. At Gallatin after dispersing the town’s defenders, Grierson turned southwest to confuse any pursuit. A small wagon train carrying a 64-pounder Parrot gun was captured and spiked, and 1,400 pounds of gunpowder were destroyed. The raiders stopped for the night at another plantation to grab some much-needed sleep.

Chased by the 20th Mississipi Infantry

By 7 am on April 28, the Federal raiders were on the move again intending to push toward Grand Gulf. Along the way Grierson dispatched a battalion of the 7th Illinois under Captain George Trafton to make a lightning strike against the New Orleans & Jackson Railroad at Bahala, creating a diversion while the rest of the column headed to Union Church. At 2 pm, about two miles northwest of their destination, Grierson’s men were resting when a Rebel cavalry detachment fired on their pickets. The Federals quickly scrambled after them, pushing the Rebels back through Union Church before halting for the night.

At 3 am on the 29th, they were joined by Trafton, who brought disturbing news. After creating havoc at Bahala and discovering an empty Confederate camp nearby, Surby and another scout learned that Adams’ cavalry was in the area and preparing an ambush on the road between Union Church and Fayette. Grierson, learning that his pursuers were increasing, decided to head back east to the New Orleans & Jackson Railroad. To throw off pursuers, he ordered a battalion of the 6th Illinois to make a demonstration toward Fayette, where Adams had set up his ambush. The rest of the brigade, soon to be joined by the diversionary battalion, set out in the opposite direction for Brookhaven, overtaking along the way a wagon train hauling several hogsheads of sugar.

At Brookhaven the troopers charged and captured more than 200 Confederate soldiers, whom they immediately paroled. They set on fire a section of trestlework, a small bridge, railroad cars, and the train station itself. By this time Adams had discovered the Yankees weren’t coming, but help was on the way. Pemberton had dispatched Colonel Robert Richardson to take command of the 20th Mississippi Infantry, which was now acting as mounted infantry, and chase down Grierson.

Despite some delays, Richardson’s force rolled into Hazelhurst around noon and set out for Union Church. After reaching there at 9 pm and learning the Yankees had left that morning, Richardson rested his men and horses for a couple of hours before setting off for Brookhaven. Two other Confederate forces, under Colonel W.R. Miles and Major James De Baun, were dispatched by Gardner from Port Hudson to aid in trapping the Federals.

After breaking camp eight miles from Brookhaven early on the morning of April 30, Grierson’s raiders pushed south along the railroad, burning bridges, trestles, railroad cars, and depots at Bogue Chitto and Summit (although the depot in the latter village was not torched since it was too close to private houses). Behind the raiders came Richardson, who linked up with Love’s command and hoped with Adams’ help to overtake and defeat Grierson.

At Summit, Grierson was informed erroneously that the Rebels had a strong force at Osyka—a rumor spread by the Confederate commander there. Grierson would later write, “Hearing nothing more of our forces at Grand Gulf and not being able to ascertain anything definite as to General Grant’s movements or whereabouts, I concluded to make for Baton Rouge.” At sunset the Federals rode south out of Summit, following the railroad toward Osyka. Once well clear of the citizens’ eyes, Grierson turned his brigade west for Baton Rouge. At dawn they stopped for a brief rest at a plantation.

Richardson’s and Love’s combined force charged into Summit at 3 am on May 1, only to find that once again the Yankees had cleared out. Although he missed Grierson, Richardson did learn from the townspeople that the Yankees were headed for Osyka. Richardson rode out of Summit intending to get ahead of the raiders and set up an ambush. By 9 am, his scouts informed him that Grierson was heading west. Richardson had no choice but to rest his worn-out men and horses for three hours before pushing on to Osyka, which he believed Grierson still intended to attack.

Clash at Wall’s Bridge

Meanwhile, the Federals continued their ride toward Baton Rouge. Ahead lay Wall’s Bridge over the Tickfaw River. Surby and his scouts were out front and discovered fresh tracks of enemy cavalry headed from Liberty to Osyka. The tracks belonged to three companies of the 9th Louisiana Partisan Rangers under De Baun, who had stopped around 11:30 am to rest and eat at Wall’s Bridge. A small rear guard half a mile to the rear was soon encountered by Surby’s scouts. Although the scouts captured a few of the pickets, a couple of shots rang out as troopers from the 7th Illinois encountered more pickets. A Confederate officer and his orderly, going to investigate, were nabbed by the scouts.

Blackburn arrived on the scene after hearing the shooting and ordered Surby and his scouts to follow him. Believing the Rebels knew of their presence, Blackburn rashly charged across the bridge. “It seemed as though a flame of fire burst forth from every tree,” Surby later recorded. Blackburn and his horse went down, while Surby took a bullet in his thigh. A platoon from G Company of the 7th Illinois under Lieutenant William Styles followed across the bridge and was met by a hail of lead that thudded into three men and seven horses. Five raiders were captured, while four others managed to escape.

When Grierson and Prince arrived, they quickly had two companies from the 7th dismount and form into skirmish lines on either side of the bridge. A Woodruff gun was positioned on the road and began hammering the Rebels in the trees across the bridge. A second gun was brought into action. Soon a battalion of the 6th Illinois was ordered to charge across the bridge, while two other battalions forded the river to flank the Confederates and send them fleeing in the direction of Osyka.

With the short fight over, the wounded were moved to a nearby plantation. Included among them was Surby, who put his own blue uniform back on for safety in case he was captured, and the mortally wounded Blackburn. Volunteering to stay behind with the wounded were surgeon Erastus Yule and two other men. Surby was right to be cautious—he and the others would be taken prisoner by Adams, who along with Richardson would soon give up the chase after being ordered to return to Port Gibson to fight Grant’s army, which had finally crossed the Mississippi.

Arrival in Baton Rouge

The Federals, meanwhile, pushed on toward Baton Rouge. Samuel Nelson was put in charge of Surby’s scouts, who again led the way. Ahead of the raiders lay Williams Bridge over the Amite River. The raiders encountered and drove off more Confederate cavalry, but not before word was sent to Gardner at Port Hudson that the Yankees were heading to Williams Bridge. A sizable Confederate force was dispatched from Port Hudson to secure the bridge, but they were too late. Pushing through the darkness, Grierson reached the bridge at midnight and continued to ride on through the night for the last river, the Comite, which lay between the Federal cavalry and Baton Rouge.

Grierson easily forded the river and overran a Rebel camp, capturing most of the troops there. The dead-tired Federals, many of them asleep in the saddle, pushed on for another four miles before stopping at a plantation to grab some rest. One of Grierson’s orderlies, sound asleep, continued on toward Baton Rouge, where he was awakened by Union pickets. He had quite a story to tell, and soon a patrol was sent out to make contact with Grierson.

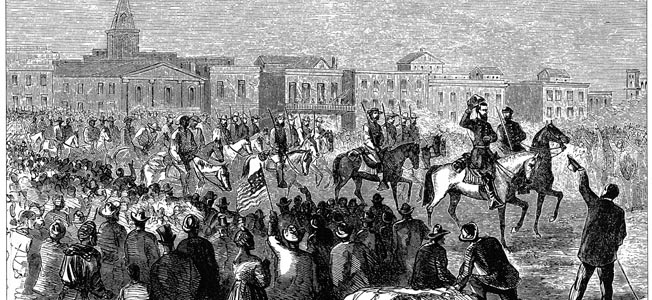

A parade was held in Baton Rouge later in the afternoon for the worn-out troopers in honor of their raid. In 16 days they had ridden 600 miles through enemy territory, destroying more than 50 miles of railroad tracks, capturing and paroling 500 prisoners, seizing 1,000 horses and mules, and tying up precious Confederate reserves who were needed at Vicksburg. With the parade over, Grierson and his tired command finally eased out of their saddles and got some well-deserved rest. All in all, it had been quite a trip.

My name is Michael Smith. My great great uncle James Henry Smith and a cousin enlisted in company B 6th Illinois Cavalry in Johnson County Illinois in 1861 and later participated in Grierson’s Raid. My great grandfather would tell stories shared by his uncle about riding through the south to Louisiana? I just started researching the 6th Illinois Cavalry and discovered the fairly famous raid. Thank you for the account.

Very Comprehensive article on one of the truly great “Raids” of the ACV, IMHO. Of course, this was the inspiration for John Ford’s movie the “Horse Soldier’s.” Although, Grierson was ostensibly portrayed by John Wayne- Wayne’s character was a “Railroad Engineer.” Some said the Duke didn’t want to portray a “Music Teacher.” Who knows for sure? It was a decent yarn on a truly great exploit.