By Stuart W. Sanders

Few Civil War officers, in either army, were as polarizing as Union Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson. Standing six feet, four inches tall and weighing more than 300 pounds, Nelson’s intimidating size and imperious manner earned him many enemies among civilians and soldiers alike. Despite Nelson’s controversial reputation, Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, commander of the Union Army of the Ohio, considered Nelson “an officer of remarkable merit. Though often rough in command, he was always solicitous about the well-being of his troops, and was held in high-esteem for his conspicuous services, gallantry in battle, and great energy.” Another officer, Brig. Gen. Charles C. Gilbert, a brigade commander in Nelson’s division, called the general an “energetic and wide-awake officer.” Other Union officers, however, were highly critical of Nelson and openly disliked the high-handed general. His years at sea had given him a sharp, wounding tongue. It would prove to be his downfall.

Nelson was born near the Ohio River town of Maysville, Kentucky, on September 27, 1824. After a local grammar school education, he attended Norwich Academy in Vermont for two years. He then became a midshipman in the U.S. Navy, attended the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, and saw active service on a ship during the Mexican War. By 1855 he had risen to the rank of lieutenant. Five years later, as national tensions flared after the election of his fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, Nelson was serving as ordnance officer at the Washington Navy Yard.

Keeping Kentucky’s Northern Alignment

During the early months of the secession crisis, it was unclear if Kentucky would remain in the Union. Federal authorities sent Nelson back to his native state to report on the Commonwealth’s political climate. With a pro slavery populace and ties to both the North and South, Kentucky’s initial stance proved to be enigmatic. After Southern forces fired on Fort Sumter, Lincoln sought 75,000 troops to quell the rebellion. When Lincoln requested soldiers from Kentucky, the Bluegrass State’s governor responded, “I say, emphatically, Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states.” As Kentucky’s status remained questionable, Nelson reached Louisville, determined to keep his native state loyal.

“Never in my life have I seen anything like the excitement there is here,” Nelson reported in mid-April 1861. “The people have absolutely gone mad.” While both sides held rallies, Nelson assured his superiors, “You can tell the President that I think Kentucky can be held still—but it will require exertion.” On April 22 he urged the administration to arm loyal Kentuckians. Although the Bluegrass State officially declared neutrality the following month, Nelson believed that Kentucky “will be true to her colors in the long run.”

feet, four inches tall and over 300 pounds, he was one of the largest generals in either army.

Nelson’s calls were heeded. With the help of a mutual friend, Joshua Speed, who as a young man had been Lincoln’s partner in a Springfield, Illinois, grocery store, the president secretly shipped 5,000 muskets to pro-Union supporters in Kentucky. Nelson took charge of the distribution efforts, with 1,200 weapons going to Louisville and the rest scattered about other cities in the state. Unionists were allowed to purchase the weapons for a nominal fee of $1 per musket.

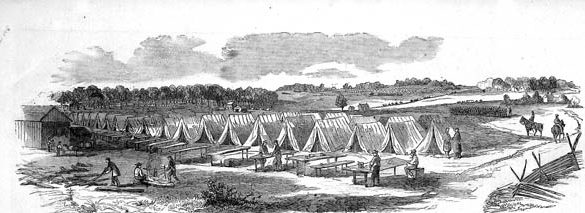

That July, Nelson was assigned another special duty to arm Kentuckians to fight in East Tennessee or eastern Kentucky. He met with Unionists in Lancaster and Crab Orchard and appointed officers to lead troops southward. Those Kentuckians—several of whom became prominent Union commanders—then began enlisting soldiers themselves. Nelson needed a place to train the recruits, so he established Camp Dick Robinson on a farm just north of Lancaster. Hundreds of recruits flocked to the camp, which became an important rallying point for loyal Kentuckians.

At Camp Dick Robinson, Nelson quickly gained a reputation for meting out harsh discipline—a carryover, perhaps, from his Navy days. The hard training, coupled with a generous dollop of saltwater profanity, alienated Nelson from volunteer troops, who were not used to being cursed at. Tempers frequently flared. Nelson was unconcerned. “War is war,” he shrugged, “and nothing will make one man march to certain death at the bidding of another but discipline; and without that we cannot whip the enemy on one hand, or protect our citizens on the other.” One way or another, Nelson got things done. Shortly after the camp was established, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer proclaimed Nelson “the most prominent man in getting up the threatened invasion of East Tennessee.” Rebel authorities recognized Nelson as an enemy officer of some consequence.

Kentucky Enters the War

In September 1861, troops from both sides poured into Kentucky. With a loyal legislature, the Bluegrass State ended its neutrality and officially sided with the Union. That same month, Union Brig. Gen. George Thomas assumed command of Camp Dick Robinson. Federal authorities officially thanked Nelson for his “good service to the cause of the Union by the zeal and untiring energy he has displayed in providing and distributing arms to the Union men of Kentucky, and in collecting and organizing troops at Camp Dick Robinson.” This renown led to a promotion; on September 16, Nelson was appointed brigadier general of volunteers. Within a month he had established another training ground, Camp Kenton, near his hometown of Maysville, where he set to work preparing for a move into eastern Kentucky.

On October 23, Nelson led troops to Hazel Green, Kentucky, where he reported capturing “several of the most notorious secessionists in this vicinity.” The next month, he was victorious at the Battle of Ivy Mountain and also skirmished with Confederates around Piketon. Nelson then operated around Prestonsburg with approximately 3,000 men, providing a strong Unionist presence in eastern Kentucky at a critical time.

An Unpopular Commander

Although Nelson’s industry and determination helped save Kentucky for the Union, his roughshod manner led to mounting complaints. Several prominent politicians urged Lincoln to send Nelson back to the Navy, where his shipboard discipline presumably would be more palatable. In August 1861, William B. Carter, a prominent East Tennessee Unionist, told Lincoln, “We must have a competent commander. It is madness to entrust the control of the military movements in East Tennessee to a Naval officer.” A month later, Kentuckian Leslie Combs informed the president, “My friend Nelson is excessively unpopular—with his command. Officers and men—have been urging me to ask his withdrawal, but I was reluctant to do or say anything that might wound his feelings. His whole education and all his habits fit him for the sea; and I hope you will soon give him a lift in his profession and transfer him to a ship.”

Union Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, a West Point-trained officer who commanded much of Kentucky for a time, recognized Nelson’s strained relationship with citizen-soldiers, telling Thomas, “Nelson has got into difficulty with the militia.” Many officers were aware of Nelson’s reputation. In late November, Buell reported, “Nelson has been in camp a day, and, I am informed, has already got into difficulty with another officer; and, if I am rightly informed, has behaved rather absurdly. As he is a veteran, some allowance must be made for him.” Like others, Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis urged Lincoln to send Nelson back to sea. “He is off of his appropriate element,” Davis wrote, “& not at all qualified to perform the duties of this place. So far as he has come into contact with citizens or soldiers in Kentucky, I think he is the most odious man I have ever known.”

Lincoln, who was grateful to Nelson for holding on to their native state for the Union, ignored all calls for the general’s removal, and in February 1862 Nelson and his division were sent to Tennessee. By early April, Buell’s command was moving toward Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army, which was camped at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River in West Tennessee. On April 6, Grant ordered Nelson to advance from his base at Savannah, Tennessee. Grant’s army was soon under attack; the Battle of Shiloh had begun.

Nelson pushed his men forward rapidly. When his troops arrived, Confederate forces had shoved Grant’s army back to the very edge of the Tennessee River. There, Nelson found thousands of soldiers crowded by the river, “frantic with fright and utterly demoralized.” Nelson tried to get them back into the action, but “they were insensible to shame or sarcasm—for I tried both on them—and, indignant at such poltroonery, I asked permission to open fire on the knaves.” In the end, Nelson refrained from shooting the soldiers—there were few enough to spare in the wake of the surprise Confederate attack. Nelson had arrived, Buell noted, at the “opportune moment,” and the Kentuckian’s division helped stifle the Confederate advance. The next morning Nelson’s men joined in the repulse of the Rebel army. After the Union victory at Shiloh, Nelson participated in the siege of Corinth, Mississippi. On July 17 he was named major general of volunteers.

82 Percent of Nelson’s Army Lost

After operating in northern Alabama, Nelson received orders from Buell in August 1862 to return to Kentucky. Confederate troops led by Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith were pressing into the state. Nelson was ordered to organize the state’s defenses and drive off the invaders. By August 25, Nelson’s advance was at Richmond, Kentucky. Two days later Nelson visited the camp and was unimpressed. He told his department commander, Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, “I find that there is no discipline among these troops. Straggling, marauding, plundering is the rule; good conduct the exception. I find this town literally overrun. I have ordered everybody to their camps, and shall enforce the strictest discipline.” At the same time, Nelson asked to be transferred, and Wright informed General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in Washington that “Nelson don’t like serving in the department; it would be well to relieve him as soon as he can be replaced. In many respects he is a good officer, too changeable however, being influenced too much by every report of Buell that reaches him.” Halleck demurred.

On August 30, Nelson learned that Kirby Smith’s army was approaching in force. He rushed to Richmond, Kentucky, from Lexington. Upon his arrival at 2 pm, Nelson “found the command in a disorganized retreat or rather a rout.” The Confederates had struck his 7,000 green troops hard and driven them from two positions. Nelson rallied about 2,500 soldiers south of Richmond, assuring them that he would “show them how to whip the scamps.” He whacked at least six skulking soldiers with the flat of his sword, and rumors later swirled that he had fatally shot two others. Charging into the thick of the action, he called to them, “Boys, if they can’t hit something as big as I am, they can’t hit anything!”

Proving to be a better general than psychic, Nelson was struck in the thigh with a bullet a moment later and carried off the field. After his wounding, Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft observed, “The whole line broke in wild confusion and a general stampede ensued.” Most of Nelson’s army was captured, and the Battle of Richmond proved to be one of the most lopsided Confederate victories of the war. Nelson himself barely escaped capture. By that evening, he was back in Lexington, where, he informed his superiors airily, he was “having a ball cut out of my leg.” Nelson left Lexington, which soon fell to Smith’s forces, and went to Cincinnati to recover. Behind him, he had lost 82 percent of his army in one day.

“We will give them a bloody welcome!”

By mid-September much of Kentucky had fallen under Confederate control. In addition to Kirby Smith’s army barreling into central Kentucky, other Rebel units moved into the eastern portion of the state. Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi entered Kentucky near Glasgow, captured a Union garrison at Munfordville, and was poised to strike Louisville itself. Buell’s army shadowed Bragg and rushed northward to save Louisville. Before Buell could arrive on the scene, Nelson arrived there from Cincinnati, took command, and bolstered Louisville’s defenses. Reaching the city on September 18, he established his headquarters at the luxurious Galt House hotel. As an important supply depot for Union troops operating in Tennessee, Louisville required a strong defense. If Louisville fell, the Confederates could take the war onto Northern soil by simply crossing the Ohio River.

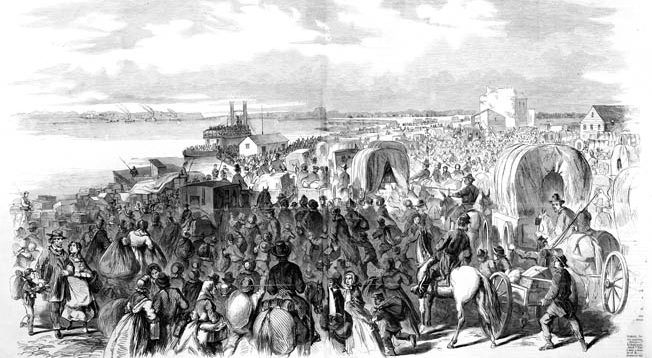

According to Union Captain Stephen Jones, when Bragg’s army threatened Louisville there was “serious apprehension” among the soldiers and “a very great panic among the citizens.” Nelson’s presence, however, may have contributed to the chaos. Union Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Boyle wrote that when Nelson took command, “he increased the excitement and alarm very much.” Building a pontoon bridge across the Ohio River to transport troops and supplies, Nelson ordered all women and children to leave the city. “Nelson had sworn that he would hold the city so long as a house remained standing or a soldier was alive,” Major J. Montgomery Wright noted, “and he had issued an order that all the women, children, and non-combatants should leave the place and seek safety in Indiana.”

The order—and the threat that he would see Louisville burn before it fell into Rebel hands—caused much of the worry. One Louisville resident wrote Lincoln that Nelson’s actions stoked fear and that “men women & children are wild with panic.” Nelson also called on the troops to defend Louisville with all their might. He exclaimed, “The rebel hordes who are now ravaging the fair land of Kentucky are advancing to attack this city. We will give them a bloody welcome!” Rumors soon spread that Nelson would be replaced, and prominent Kentuckians rallied to his defense. Governor James F. Robinson and the state’s two U.S. senators asked Union authorities to retain him. “The fate of Kentucky is hanging in the balance,” they wrote. “Movements here are of the greatest importance. Nelson comprehends the whole theater. I council his presence and command here as indispensable. He can render greatly more service here than he can upon any other theater.” Fears were allayed when, on September 24, more Union forces approached the city. “Louisville is now safe,” Nelson reported. “God and liberty.”

Feud Between Nelson and Davis

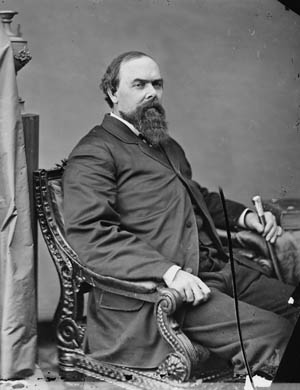

Before Buell arrived, Nelson made a fateful, if unwitting, decision. Shortly after assuming command, he gave Union Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis the job of organizing local men into a fighting force. On the surface, Davis, a respected officer, appeared to be a good choice. Born in Clark City, Indiana, on March 2, 1828, Davis was (like Nelson) a Mexican War veteran who had steadily moved up the ranks of the regular army. By 1861 he was a captain commanding an artillery battery at Fort Sumter. That August, his friend Indiana Governor Oliver Morton named Davis colonel of the 22nd Indiana Infantry Regiment. Four months later, Davis was promoted to brigadier general. Subsequently, he fought at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and commanded divisions at Pea Ridge and Corinth.

Unlike the bull-like Nelson, the unfortunately named (for a Union general) Davis was on the smallish size. Buell’s adjutant, Colonel James B. Fry, described Davis as “a small, sallow, blue-eyed, dyspeptic-looking man, less than five feet nine inches high, and weighing only about one hundred and twenty-five pounds.” Fry, who had served in the same regiment as Davis in the Mexican War, added that his fellow officer was also “brave, quiet, obliging, humorous in disposition and full of ambition, daring, endurance, and self-confidence.” At least some of those attributes would soon get Davis in trouble with Nelson.

In July 1862, Davis fell ill and left the Deep South for Cincinnati. When Louisville was threatened a month later, Wright sent Davis there to report to Nelson. Upon Davis’s arrival, Nelson told him to take charge of the civilian units. Nelson expected the order to be followed to the letter. Davis, however, believed the duty to be beneath that of a regular army officer, amounting merely to organizing “a rabble of citizens.” Davis’s attitude would quickly reveal itself to Nelson, with dire results for both men.

When defensive preparations were under way, Nelson asked one of his officers how Davis’s work was progressing. The officer responded, “General Davis must be worse, for he has been sitting on the heaters most of the time [trying to stay warm] for the last four days.” Nelson told the officer that he wanted to see Davis immediately. The order irritated Davis, who “appeared offended [and] jumped from the heater upon which he had been sitting, and followed me to General Nelson’s headquarters” at the Galt House.

“Well, Davis,” Nelson asked the Hoosier general, “how are you getting along with your command?” Davis shrugged and responded, “I don’t know.” Nelson cocked his head. “How many regiments have you organized?” Again Davis said, “I don’t know.” Nelson asked, “How many companies have you?” The response was the same: “I don’t know.” Nelson stood up. “But you should know,” he spat. “I am disappointed in you General Davis. I selected you for this duty because you are an officer of the regular army, but I find I made a mistake.” Davis also stood up, apparently wagging his finger at his superior officer, and said, “General Nelson, I am a regular soldier, and I demand the treatment due to me as a general officer. I demand from you the courtesy due to my rank.”

“I will treat you as you deserve,” Nelson replied. “You have disappointed me; you have been unfaithful to the trust which I reposed in you, and I shall relieve you at once.” He ordered Davis to Cincinnati to report to Wright.

“You have no authority to order me,” Davis said. Nelson looked at his adjutant general and barked, “Captain, if General Davis does not leave the city by nine o’clock to-night, give instructions to the provost-marshal to see that he shall be put across the Ohio.” Fuming, Davis left for Cincinnati.

Contentious Relationship Between Governor Morton and General Nelson

According to Union Brig. Gen. Charles C. Gilbert, the sour relationship between Nelson and Indiana Governor Morton was the genesis of the trouble. When Davis arrived, Gilbert wrote, he “reported to General Nelson for duty. He was assigned to duty in the city of Louisville instead of with the Army of Kentucky. This seems to have offended Davis. But General Nelson did not intend that he should have any place in that army, because he was supposed to be a friend of Governor Morton, whose influence Nelson from the very first resolved to restrict to the narrowest limits. Morton had made trouble in the Army of the Ohio, and Nelson was resolved to be on his guard against him in the Army of Kentucky.”

While Nelson abhorred Morton’s involvement in Army affairs, the governor despised Nelson because the Kentuckian had lost some 1,500 Indiana troops in the Federal debacle at Richmond and then blamed a Hoosier officer, Brig. Gen. Mahlon Manson, for the defeat. By the time Davis reached Cincinnati, Buell had arrived in Louisville and assumed command. Wright sent Davis back to Louisville to take charge of his division, which had marched northward with Buell, giving Davis the good but unheeded advice to stay out of Nelson’s way, avoid gossiping with other officers, and keep his own opinions to himself. On his way back to Kentucky, Davis stopped off in Indianapolis and paid a visit to Governor Morton. Together, the two traveled to Louisville. Nelson’s troubled history with Morton would soon come to a head.

Confrontation at the Galt House

On the morning of September 29, Nelson ate breakfast at the Galt House. After eating, he went to the front desk to inquire whether Buell had breakfasted yet—he needed to speak with him. Told that the Army commander had not yet come downstairs from his second-floor room, Nelson turned away, taking a moment to regard the crowd in the hotel lobby. He was wearing the full blue-and-gold dress uniform of a U.S. Army general. Beneath his open coat he wore a bright white vest. He was, said one onlooker, “the most conspicuous feature of the grand hall.”

As Nelson stood near the hotel office, he saw an unwelcome trio of Indianans approach: Oliver Morton, Captain Thomas W. Gibson, and worst of all, Jefferson C. Davis. Another officer on the scene, Major James H. Cole, noticed that Davis “looked pale and was evidently laboring under unusual excitement.” Cole, expecting trouble, had already told Nelson that Davis was in the hotel. True to form, Nelson stepped up to the Hoosiers, Cole wrote. Davis stepped forward. In “haughty tones,” said Cole, Davis asked, “General Nelson, I want to know why you disgraced me by placing me in arrest?” Nelson said, “Do you know who you are talking to, sir?” Davis said, “Yes! Bill Nelson!”

When Nelson told him to leave, Davis kept talking. “Sir, you seemed to take advantage of your authority the other day,” Davis insisted. “I want to know why you disgraced me by placing me under arrest.” Mockingly putting his hand to his ear, Nelson said, “Speak louder, I don’t hear very well.” Davis repeated his demand for an apology. “Go away, you damned puppy,” Nelson said. “I don’t want anything to do with you.” Davis, who had been nervously crumpling a hotel visiting card in his hand, flipped the ball of paper into Nelson’s face. Nelson instantly slapped him on the side of the head with his open hand. After smacking Davis, Nelson turned to Morton. “Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?” With Nelson looming above him, Morton told him no. According to Buell, “Nelson then turned to Morton, denounced him for appearing as an abettor of the insult forced upon him, and retired toward his room in the adjoining hall.” On the way, Nelson turned to another onlooker, Alf Burnett, and demanded, “Did you hear that God Damned insolvent scoundrel insult me, Sir? I suppose he don’t know me, Sir. I’ll teach him a lesson, Sir.”

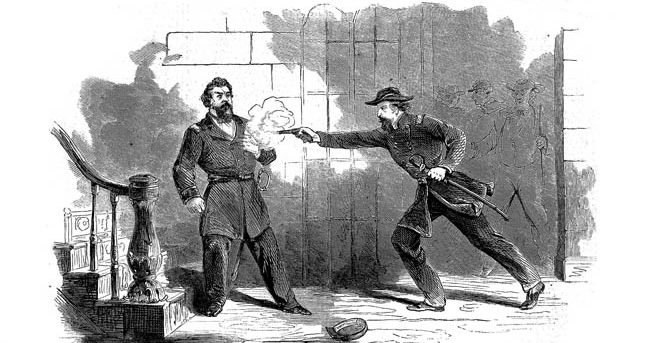

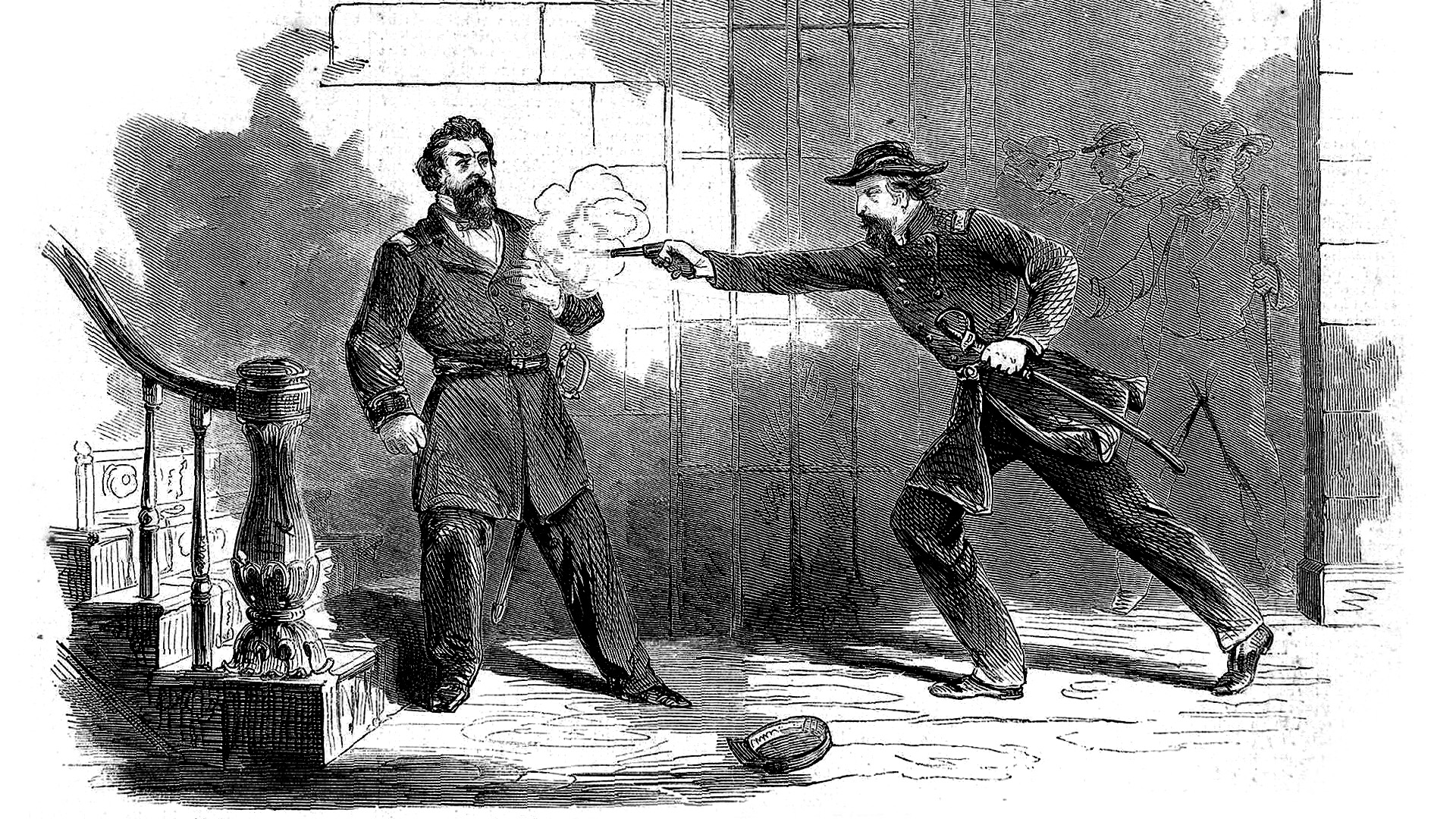

As Nelson walked away, Davis told him ominously, “I will see you again.” Davis then borrowed a Tranter pistol from Gibson and followed Nelson down the hall. Nelson went upstairs to his office—many thought that he was going to get a gun of his own. Captain William T. Hoblitzell rushed after Davis in a futile attempt to keep him away from Nelson, who by that time had reappeared at the top of the stairs. “General Nelson, take care of yourself,” Davis called. He walked to within three feet of Nelson, aimed, and fired. (Davis would later claim that the gun had gone off by accident.) The bullet struck the Kentuckian above the heart, severing one of the two main arteries. Despite the severity of the wound, Nelson staggered away and collapsed near Buell’s room. Cole noted that Nelson was unarmed.

“Tom, I am Murdered”

When the shot rang out, Nelson’s friend Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden was eating breakfast in the hotel. Upon hearing that Nelson had been injured, Crittenden raced upstairs and found Nelson lying on the floor. Crittenden took Nelson’s hand and asked, “Nelson, are you seriously hurt?” Nelson replied, “Tom, I am murdered.” Nelson also spoke to the hotel owner, Silas F. Miller. “Send for a clergyman,” he said. “I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered.” Dr. Jeremiah J. Talbot, the Episcopalian chaplain of the 15th Kentucky Volunteers, rushed from the dining room to Nelson’s side, asking the stricken general if he was ready “to accept Jesus Christ as his savior and forgive anyone who had ever wronged him.” Nelson retained something of his characteristic brusqueness. “Baptize me in that faith, quick!” he said. “Now! For I am going.” Surgeon Robert Murray, Buell’s medical director, arrived on the scene, but there was nothing he could do. Nelson died at 8:30 am.

Davis was placed under arrest by Captain James Fry and Adjutant William H. Spencer and confined to a room on the upper floor of the hotel. He gave conflicting accounts of his actions, telling Fry that “he did not come to the hotel that morning with murder in mind.” He said the unfamiliar pistol, which had a hair trigger, had gone off accidentally. He did admit to Fry, in the strictest confidence, that he had intended to demand an apology from Nelson and that if he did not receive one, he planned to insult Nelson and see what happened. To another officer, James Merriwether, Davis told a different story. He “had to do it,” Davis said. “For a member of the regular army not to resent an insult of that kind would make me be as low as the dog that sleeps under my father’s floor.” To no one, then or later, did Davis express even a glimmer of regret over the killing.

For the civilians and soldiers who had been preoccupied with the Confederate invasion of Kentucky, the shooting was, an officer wrote, “as unexpected as it was shocking.” Garbled first reports claimed that Confederate President Jefferson Davis had slipped into Louisville and assassinated Nelson. Soon it became known throughout the ranks that Jefferson C. Davis had been the shooter. Buell remarked that the murder “caused much indignation among the troops that knew him best.” There were fears that the men of Nelson’s former division would extract revenge, particularly after members of the 6th Kentucky Regiment pledged to kill Davis on sight. Therefore, Cole related, “the Provost Guard was ordered to the hotel to prevent excited officers and soldiers from perpetrating acts of violence.” Confederates, of course, were joyous to hear the news. One soldier, E.O. Guerrant, confided in his diary that “General Nelson certainly dead killed at Galt House Louisville by General Jeff Davis. He was a great scamp.”

New York Times correspondent Franc Wilke, who had suffered his own run-ins with Nelson in the past, rushed his verdict into print. Nelson, he wrote, “was a brave soldier and a fairly good leader, but in this instance the overbearing brute found a man he could not insult with impunity.” The influential Indianapolis Daily Journal went even further in blaming the victim for his fate. On the day after the shooting, the newspaper announced with magisterial confidence: “We know enough of the characters of the two men to be very sure that Nelson acted with most unbearable insolence, and that Davis was not insulting or ungentlemanly in his language. Nelson was overbearing, harsh, inconsiderate, and impatient, with no regard for the feelings of others, and none for the ordinary decencies of life. He was heartily hated by every man he ever commanded, and not a few have threatened that if they ever got into battle with him they would not be under him for long.” The Daily Journal also reprinted slanderous reports that Nelson had slashed six Indiana soldiers insensible with his sword and fatally shot two others. The men of the 8th Kentucky were said to have given three cheers in camp “that a tyrant of the first water had been killed.” It was widely—and erroneously—believed that Nelson had struck the first blow. Few had seen Davis throw the paper wad into Nelson’s face.

Some higher ranking officers, including Brig. Gens. James S. Jackson and William R. Terrill, wanted Davis hanged on the spot, but others came to his defense, including department commander Horatio Wright. Buell and Cole both condemned Morton for his involvement. Cole believed that if the governor had stayed on Hoosier soil, the two generals probably would have sorted out their differences. Buell, for his part, said “the fine Italian hand of Morton sowed the seed of mischief.” They were both correct—Morton’s presence was like oil on a fire. Less than an hour after the shooting, Morton left for Indiana. Ironically, he probably crossed the Ohio River on the pontoon bridge that Nelson had ordered constructed.

No Justice For Nelson

Although Davis was arrested, Federal authorities never formally charged him with murder. The Army was too engrossed with the Confederate invasion of the state to worry about personal matters, however sensational. Buell, noting that there were not enough officers available to convene a court martial, wrongly assumed that military authorities in Washington would appoint a tribunal to look into the case. Two days after Nelson’s death, Buell’s army marched out of Louisville, where, on October 8, they met and defeated the Confederates at the Battle of Perryville. Five days later, Wright ordered Davis released from close arrest, reporting falsely to the War Department that no charges had been preferred against Davis, that the period to hold him without charges had expired, and that Davis had acted in self-defense. No one questioned Wright’s false assertions, then or later.

Although a Jefferson County grand jury eventually indicted Davis for manslaughter on October 27, bail was placed at a rather low $5,000. Davis quickly made bail and returned to active duty. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase was the lone voice inside the Lincoln administration seeking justice for the slain Nelson, writing Lincoln: “Under no circumstances whatever, in my judgment, can personal violence by one officer to another—much less the killing of one officer by another—be passed over without the arrest and trial of the offender, except at the cost of serious detriment to this service and serious injury to the respect due you as Commander in Chief. Nelson was imperious, overbearing, arrogant, insulting, but these faults should not be received as grounds for dispensing with a trial.”

Lincoln, an attorney himself, was strangely quiet on the matter. His best friend in his early days in Springfield, Illinois, had been Joshua Speed, and Jefferson C. Davis’s defense attorney was James Speed—Joshua’s brother and the future U.S. attorney general under Lincoln. Besides the Speed connection, Lincoln was also influenced—as always—by political and military considerations. Indiana Governor Morton was a powerful and important ally, and Morton’s large levy of state troops for the Union cause was crucial to the continued prosecution of the increasingly costly war. The removal of Don Carlos Buell from command of the army following the Battle of Perryville, and the deaths in that battle of two of Nelson’s closest allies, Brig. Gens. William Terrill and James Jackson, eliminated the highest ranking voices who might have demanded justice for Nelson.

On May 24, 1864, the manslaughter charge against Davis was dismissed with the option to reinstate it later on the motion of Davis’s attorney, James Speed. The charge was never reinstated. Davis served competently as a brigade commander for the rest of the war, seeing action in all the large battles in the Western theater, including Stones River, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and William Tecumseh Sherman’s Georgia campaign. The fact that Davis was never promoted to major general, despite several recommendations by his commanding officers, may have been Lincoln’s lone concession to justice in the case.

Later in the war, Union Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson stopped by Davis’s headquarters. Johnson said that Davis looked “gloomy and sad.” Johnson asked Davis what was wrong, and the Hoosier responded, “Johnson, you have never had the cross to bear which has weighed me down.” Johnson, for his part, had little sympathy for his brother general. “Military law, as Davis well knew, offered prompt and ample redress for all the wrong Nelson had done to him at the first meeting,” he wrote. “But Davis made no appeal to law. On the contrary, he deliberately took all law into his own hands. I do not doubt that Morton, and perhaps others without foreseeing the fatal consequences, encouraged Davis to insult Nelson publicly for the wrong done in an official audience.”

Burying Nelson and Davis

After the war, Davis remained in the Army and became colonel of the 23rd U.S. Infantry. He was posted in Alaska—punishment in itself—and later fought in the brutal campaign against the Modoc Indians. On November 30, 1879, he died in Chicago of natural causes and was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Nelson’s remains were not permitted to rest quietly. After his funeral the day after the shooting, Nelson was interred in Louisville’s Cave Hill Cemetery. Plans were made, however, to move his body to Camp Dick Robinson. In August 1863 his corpse was transferred to Lexington by rail. Local Unionists met the remains “to give it a fitting reception.” According to diarist Frances Peter, when Nelson’s body arrived, “A salute was fired from the fort as the cars entered the town and a procession of citizens and 1st Ohio and 48th Pennsylvania escorted the hearse from the Louisville to the Nicholasville cars which were to take the body.” Nelson was reinterred at Camp Dick Robinson, but vandals repeatedly damaged his grave. Ultimately, the general’s remains were moved to Maysville, his hometown. By then his murder had long since been forgotten, as had his signal service to the nation in preserving Kentucky for the Union cause.

Thank you for preserving this tale of caution. Honest introspection of human nature supports a conclusion that excessive personal pride on all sides over professional conduct leads to calamity in so many ways. Surely these men were brave patriots, but narcissism buried them both. Bull died the day he was shot. Jeff arguably died professionally and spiritually the same day he killed Bull. Who said that when two people disagree on everything then they are both not needed? Unbridled politics as usual?