By Gene. E Salecker

Among the many objectives facing General Douglas MacArthur on his return to the main Philippine island of Luzon in 1945 was the recapture of the tiny island of Corregidor.

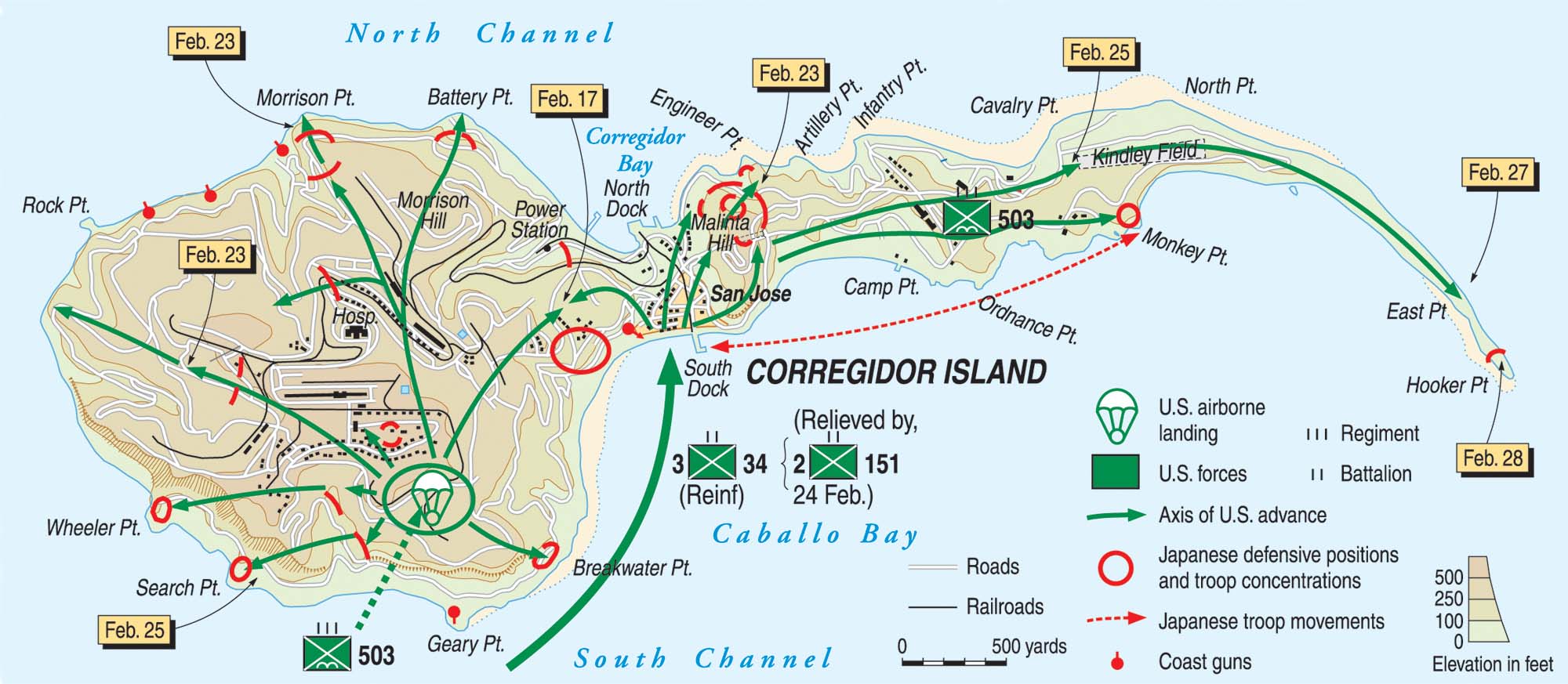

Although Manila could be taken with conventional ground forces aided by both armor and artillery, Corregidor, nicknamed “The Rock,” would be a harder nut to crack. Situated only two miles off the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula at the 16-mile-wide entrance to Manila Bay, the large-caliber guns on the island could devastate any ships going into or out of Manila Harbor. Shaped like a giant tadpole, Corregidor’s bulbous head measured roughly 11/2 miles from side to side and faced almost due west toward the South China Sea while its two-mile-long tail snaked to the east, pointing back toward Manila. While most parts of the tail were only about 25 feet above sea level, the head rose 500 feet above the waters of the bay. Having lived on The Rock for approximately two months in early 1942 when the Japanese invaded the Philippines, MacArthur was more than familiar with the defensive capabilities of Corregidor.

The Three Regions of Corregidor

Corregidor was broken into three geographical regions, Bottomside, Middleside, and Topside. Bottomside began at the neck of the island, where the head connected to the tail, and ran eastward, containing all of the tail section. The only barrio, or village, on the island, San Jose, was situated on the southern side of the neck and had served before the war as a housing area for civilian personnel and the dependents of the Philippine Scouts. Boat docks were located on both sides of the neck. On the far eastern end of the tail, on a long strip of flattened land, was Kindley Field, the only airstrip on the island.

Just east of San Jose was a huge dimple of land known as Malinta Hill. Cut into the hill was Malinta Tunnel, which ran straight in for 1,400 feet with perpendicular tunnels running off the main line. The numerous tunnels, built years before the war, contained an underground headquarters, hospital, mess area, a power generator, living quarters, and a quartermaster area. During his time on Corregidor, General MacArthur had housed his staff members, as well as his wife, young son, and his son’s nursemaid, inside the relative safety of the thick, bombproof tunnel complex.

The area on Corregidor known as Middleside began just west of San Jose, where the ground began rising toward Topside. Middleside consisted of a small plateau holding the officer and NCO family quarters, as well as a small hospital, a school, and a service club. A few hundred yards above the plateau was Topside, the pinnacle of Corregidor’s bulbous tadpole head. Consisting of an even bigger plateau, Topside held a brick headquarters building, numerous brick and mortar “Mile-Long Barracks” buildings, a parade ground, and a nine-hole golf course.

While numerous deep ravines and trees, brush, and large boulders dominated the heights, sheer cliffs on the north, west, and south led straight down to the sea. Situated around the edges of Topside at strategic locations were 23 coastal defense batteries housing 56 12-, 10-, 8-, 6-, and 3-inch guns. Surrendered by the Spanish to the Americans in 1898, it had remained in American hands until May 5, 1942, when it was finally surrendered to the Japanese during their conquest of the Philippines.

Assault by Air and by Sea

As General MacArthur and his forces moved in on Manila from both the north and south in 1945, the capture of Corregidor became crucial. With Corregidor dominating the entrance to Manila Bay, the Japanese guns on the island prevented the Americans from bringing in ships to supply or support the ground forces driving on the city. Working with intelligence reports that indicated there were no more than 900 Japanese soldiers on Corregidor, MacArthur chose General Walter Krueger and his Sixth Army to recapture The Rock.

Krueger was given three choices. He could seize Corregidor with a parachute drop, with an amphibious landing, or with both. Knowing that a parachute drop by itself would be too risky and a lone amphibious assault would be too costly, Krueger chose both. The Japanese had staged an amphibious assault in May 1942 against a half-starved American garrison and had suffered terrible losses. Krueger reasoned that the way to tackle Corregidor was with a combined air and sea attack.

As envisioned by Krueger, the main assault would come from the air. Krueger would drop the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team (PRCT) on Topside to seize the high ground while a reinforced battalion from the 34th Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division made an amphibious assault from the tip of the Bataan Peninsula, which would be wrestled away from the Japanese just prior to the attack. In all, four reinforced battalions, more than 4,500 men, would attack Corregidor, more than enough to overwhelm 900 Japanese soldiers.

The 503rd PRCT

The 503rd PRCT was a veteran unit. Activated at Fort Benning, Georgia, on March 10, 1942, the 503rd had been the first paratroopers sent to the Pacific, arriving in Australia in November 1942. Almost a year later, on September 5, 1943, the 503rd became the first American paratroopers to be dropped into combat in the Pacific, seizing an airstrip at Nadzab, near Lae, during General MacArthur’s drive along the northern coast of New Guinea. Several months later, on July 3 and 4, 1944, the 1st and 3rd Battalions were dropped onto the island of Noemfoor, near the northwestern end of New Guinea, in conjunction with an amphibious landing by the 158th Regimental Combat Team.

Although plans had been formulated to drop the 2nd Battalion on July 5, miscalculations with the altimeters on the lead C-47 drop plane had caused the men from the first two battalions to drop from only 125 to 150 feet onto the hard coral surface of a Japanese airfield runway. After suffering almost nine percent casualties to jump injuries, including the loss of one battalion commander, three company commanders, the regimental communications officer, the regimental surgeon, and numerous key noncommissioned officers, the 2nd Battalion was brought over to the island by landing craft on July 9.

After helping to clear the Japanese off Noemfoor Island, the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) had been given time to rest and recuperate. In mid-September, Company C of the 161st Airborne Engineer Battalion and the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion had been attached to the paratroopers, bringing the 503rd up to the capacity of a full regimental combat team.

On November 11, the entire unit had been moved to Leyte Island and placed in reserve during MacArthur’s return to the Philippines. A month later it had made an amphibious landing on the island of Mindoro against no enemy opposition. Since December 1944, the paratroopers had been sending out long-range reconnaissance patrols around Mindoro, with very little to show for their efforts.

Considering themselves a veteran unit, morale sank when the paratroopers of the 503rd discovered that the 511th PIR, a “junior parachute unit,” was dropped on Luzon. Captain Charles H. “Doc” Bradford, the 2nd Battalion surgeon, wrote, “It seemed again that we would be in reserve, while the big operations in Luzon were carried out by other units.” On February 5, 1945, however, morale soared when Colonel George M. Jones was notified that the regimental combat team was about to make another combat jump, this time onto Corregidor.

Planning the Jump: “The margin of safety was practically zero…”

The jump was scheduled for February 16, and in the next 11 days Colonel Jones and his staff had much to do. On February 6, Jones made an aerial reconnaissance flight over Corregidor with a group of low-level bombers to get a good look at his target. Upon return to base, he contacted General Krueger and picked Kindley Field on Corregidor’s tail for his drop zone. He was immediately overruled. Krueger wanted the paratroopers dropped on Topside so that they would have the advantage of the high ground for the support of the amphibious landing. Although much of Topside was covered by the ruins of the prewar barracks buildings, officers’ homes, and headquarters building, Jones managed to find two seemingly safe spots to drop his men—the parade ground and the golf course.

While Corregidor’s parade ground measured 325 yards long and 250 yards wide and the golf course was roughly 350 yards long and 185 yards wide, both areas were surrounded by tangled undergrowth that had sprung up since 1942, by trees shattered during air and naval bombardments, and by wrecked buildings. Additionally, both areas were pockmarked by bomb and shell craters and were littered with debris, and both fell off sharply at the edges and, on the west and south, gave way to steep cliffs. Although far from ideal jump zones, they were the best that could be found under the circumstances and would provide the paratroopers the advantage of the high ground.

Next, Colonel Jones and his staff had to figure out the prevailing winds over Manila Bay, calculate the correct speed and direction of approach for the C-47s, and determine the optimal jump altitude. It was discovered that the winds over Topside generally came from the east and blew between 15 to 25 miles per hour. Figuring that the C-47s could approach from southwest to northeast at an altitude of 400 feet above Topside, each plane would be over the small drop zones for no more than six seconds. Calculating that it took each paratrooper approximately a half second to get out of the plane and another 25 seconds to reach the ground, it was figured that each man would drift 250 feet to the west during his fall, giving him only 100 feet of safety in case of a sudden wind gust or human error.

With two separate drop zones, it was decided to use two columns of C-47s from the 317th Troop Carrier Group to drop the men. With only six seconds of drop time before the plane was past either drop zone, only six to eight troopers could be dropped at one time. Each plane would have to circle around, one column to the left, the other to the right, and get back in line at the end of the column a couple of times until everybody was safely out of the plane. With the airplanes approaching from the southwest and flying over the island at a diagonal, they at least eliminated the chance of a late jumper falling off the cliff and landing in Manila Bay. Instead, a late jumper would land either on the eastern end of Topside or, at worst, on Middleside.

“Planners knew,” wrote historian Robert Ross Smith, “that they were violating the [theory] … to get the maximum force on the ground in the minimum time. But there was no choice. Terrain and meteorological conditions played their share in the formulation of the plan; lack of troop carrying aircraft and pilots trained for parachute operations did the rest. The margin of safety was practically zero…”

Undoubtedly, when some of the men heard that they would be jumping onto a drop zone approximately 300 feet by 200 feet on top of a 500-foot-high “rock,” they must have thought that the planners were crazy. When Doc Bradford expressed his doubts to Major Ernest C. Clark, Jr., of regimental headquarters, the major replied, “That’s the beauty of it…. The Japs will never expect it because it looks impossible. No army in this war has pulled anything like it. But our intelligence has got it figured out, and they say it’ll be as easy as opening a kit-bag.” Doubts were raised even higher, however, when it was learned that Colonel Jones expected 20 to 50 percent casualties from the jump into a cluttered, wreckage-strewn area.

Three Drops

In drawing up his plans for the actual assault, Jones decided that since he only had a small number of C-47s to work with and since the drop zones were so small that he would have to bring his paratroopers in via three lifts. Two lifts would come in on the first day, February 16, and the last on February 17. All the planes would be taking off from Elmore and Hill Airstrips near San Jose on Mindoro to fly the 140 miles to Corregidor, a flight time of about one hour and 15 minutes.

According to Jones’ plan, the first group would jump at 8:30 am from 51 C-47s and consist of the entire 3rd Battalion, Lt. Col. John R. Erickson commanding; the staff officers and radio operators from RCT headquarters; and Company C of the 161st Airborne Engineer Battalion. The 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion would be represented by a section of Headquarters Battery, all of Battery A with its four 75mm pack howitzers, and the 3rd Platoon from Battery D equipped with eight .50-caliber heavy machine guns. The first group had the objective of securing both drop zones for the following two lifts and providing covering fire from above for the intended amphibious landing, which was scheduled to hit the southern beach near San Jose at 10:30 am.

After the infantrymen were ashore, the second group of paratroopers would arrive at 12:15 pm using the same 51 C-47s that had dropped the first group. Led by Major Lawson B. Caskey, commander of the 2nd Battalion, the group would contain the entire 2nd Battalion; another detachment of RCT headquarters; the Service Company, 503rd PRCT; the remaining engineers from Company C, 161st Airborne Engineer Battalion; the 2nd Platoon from D Battery with its .50-caliber machine guns, and Battery B with its 75mm howitzers, both from the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. After landing, Caskey’s men were to link up with Erickson’s paratroopers and help eliminate any Japanese on Topside.

Finally, the third drop would take off from Mindoro at 7:15 am the next day, February 17, in 43 C-47s and make the combat drop at 8:30. This last group would be made up of the entire 1st Battalion led by Major Robert Woods; the remaining men of RCT headquarters; the 1st Platoon of Battery D with its .50-caliber machine guns, and Battery C with its 75mm howitzers from the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. Their objective was to assist the other two battalions and begin clearing the rest of Corregidor.

For the first time in the Pacific, the parachute drop would use a control plane. Since there were so many variables and risks concerned with this jump, Colonel Jones would not be jumping with the first stick of men. Instead, he would be flying “about the drop zones” in a C-47 using a radio link with the other planes. Jones was “charged with the missions of correcting the line of flight and/or altering the count of the jump masters based on observations of sticks already dropped.” Once everything was going as planned, Jones would leave the control plane and parachute down to take command.

Preparing For the Assault

To prepare the area for the paratroopers and try to eliminate as many Japanese defenders as they could before the actual drop, planes from the Fifth and Thirteen Air Forces had begun pounding Corregidor on a daily basis since January 22. By February 16, both groups had flown a combined 1,012 sorties against The Rock, dropping a total of 3,128 tons of bombs.

On February 13, with just three days to go, U.S. Navy minesweepers swept the waters around the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor while cruisers and destroyers from Task Group 77.3 began shelling the island. The Japanese on Corregidor returned fire from their big guns, however, and managed to damage two destroyers and a minesweeper. In response, the task group was strengthened on February 15 with three heavy cruisers and five more destroyers.

On the morning of February 15, infantry from the 151st Regimental Combat Team, 38th Infantry Division made an amphibious landing on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula, seizing the port of Mariveles with little opposition. As the 151st moved inland, the reinforced combat team of the 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Division was brought ashore in preparation for its amphibious attack on Corregidor the next morning.

By the evening of February 15, all the paratroopers were eager and ready to go. “There was a sentimental aspect about retaking The Rock,” wrote Captain Magnus L. Smith, an assistant operations officer for the 503rd PRCT. “Everyone wanted to get in on the show and do what he could. This spirit ran down the chain of command from General MacArthur to the riflemen, sailors, and tail gunners on the aircraft.” To further instill eagerness into their troops, the officers of the 503rd PRCT showed captured Japanese movies of the American surrender of Corregidor at their homemade outdoor theater. Depicted in the film were scenes of Japanese soldiers mistreating American captives and stomping on an American flag.

Three Minutes Behind Schedule

The 3rd Battalion troopers were awakened at 5 am on February 16 and given an hour to eat, gather their gear, and board their assigned trucks. As with their earlier jumps, each truck was numbered and each waiting C-47 had a corresponding number. After the trucks reached either Elmore or Hill Airfield, the men simply got out of the truck, looked for the corresponding number on one of the C-47s, and then lined up in preparation for the call to climb aboard.

Private First Class Chester W. Nycum of Company G recalled the entire ordeal. “We load on to a convoy of trucks, which are then off to the airstrip where we are directed toward banks of stacked parachutes, each man taking one and strapping it on. We adjust ourselves, and each other, starting to look like a flock of mean, heavily armed penguins as we waddle around fastening our loads.”

Around 7:15 am, the C-47s started taking off from the two airfields on Mindoro and began circling until all 51 planes were in the air. Then, lining up in a formation of Vs, the flight headed northwest toward Corregidor, protected along the way by an umbrella of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter planes. Ahead of them, flights of Consolidated B-24 Liberator and North American B-25 Mitchell bombers and Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers were bombing and strafing Corregidor from tail to head, paying particular attention to the areas around the drop zones. Not to be outdone by the aircraft, Navy cruisers and destroyers added their shelling to the cacophony of noise over Corregidor, paying particular attention to the southern beaches around San Jose, site of the intended amphibious invasion.

When the transports and fighters were approximately six miles from the drop zones, the C-47s began to form into two columns with a prescribed 500 yards between each plane, 25 or 26 planes per column. The right column would drop the men of Regimental Headquarters, the artillerymen, and H Company on the parade ground, designated Drop Zone A. The left column would drop G and I Companies and the airborne engineers on the golf course, Drop Zone B. Inside every transport, every jumpmaster instructed his stick to stand up, hook up, and make their equipment checks.

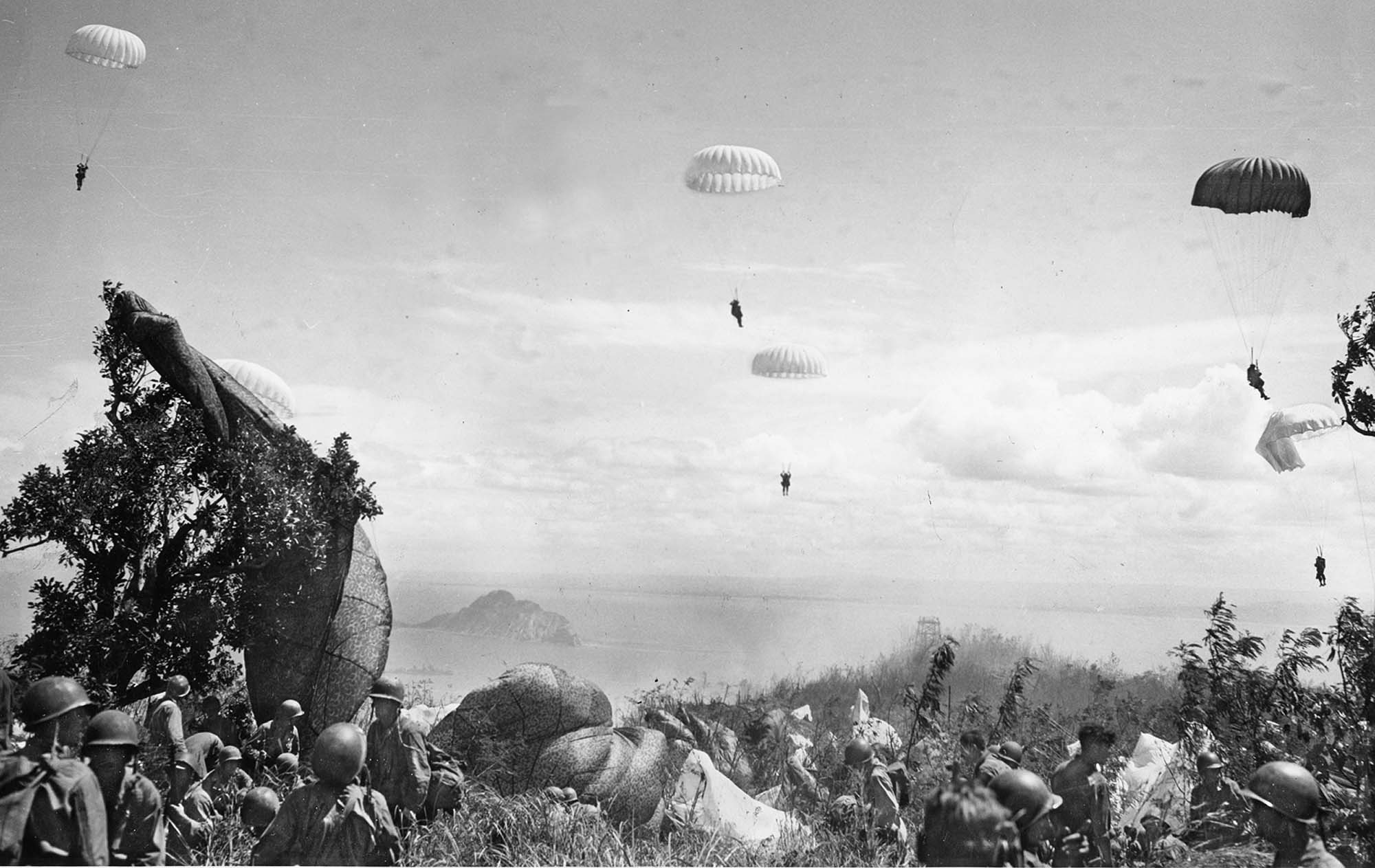

In the first plane behind the control plane, Colonel Erickson stood in the door waiting for the green “Go” light. Twenty-three other troopers stood behind him, waiting for their turn to jump on the parade ground. As the C-47 flew over Battery Wheeler, a large gun emplacement on the southwest tip of Topside, the pilot flipped on the green light. The time was 8:33 am, three minutes behind schedule.

Rough Landing on the Parade Ground

As planned, only seven other men followed Erickson out of Plane No. 1 before the C-47 passed the safe drop area. Even then, the men realized that there had been a miscalculation. The wind was blowing in excess of 25 miles per hour out of the east, and the high jump altitude of 550 feet meant that the men were being blown toward the west—toward the steep 500-foot-high cliffs that led down to the waters of Manila Bay.

Being the first out of the plane, Colonel Erickson landed safely atop Topside in the area of the bomb-blasted parade ground. As he recalled, “Considering the location of my landing, the terrain, and the fact that the area was covered with the jagged stumps of bomb-blasted trees, I was lucky. I had only minor bruises and scratches and was able to get on with my job.” The last man of the eight-man stick landed on the very edge of the parade ground.

Watching from his control C-47, Colonel Jones immediately realized that he had to make adjustments, and quick. The next plane was only 500 yards behind the first and coming in at a speed of 100 miles per hour. Instantly Jones was on the radio, telling all of the pilots to drop to an altitude of only 400 feet and shorten the number of men in a stick from eight to five or six. “This did the trick pretty well,” admitted Jones, “and contrary to some reports we had no people who landed in the water.”

Unfortunately, the three-week aerial bombardment and the preinvasion bombing and shelling had turned Topside into a jumble of deadly obstacles, especially in the area of the parade ground, which was surrounded by buildings. American bombs and shells had demolished all the buildings and had left the area strewn, according to 1st Lt. Edward T. Flash (Co. F), with “bomb craters, sharp cement boulders, tin, glass, steel bloom from the nearby buildings, and sharp tree limbs sticking skyward.” It was no wonder that the Japanese had not prepared Topside against an airborne invasion. The Americans had done it for them.

Killing the Japanese Commander

While the parade ground area was littered with huge chunks of concrete and jagged tree limbs, the small nine-hole golf course turned out to be a better place to land. “We jumped at about 400 feet,” admitted Pfc. Reynaldo Rodriquez (Co. G). “I believe this was one of the lowest-level combat jumps made by U.S. parachute troops in World War II…. I was just a little over the treetops that lined the golf course when my parachute blossomed. I came crashing down on the edge of the course. I quickly slipped out of the harness, ran to the assembly area and we established a perimeter around the golf course.”

One of the first men to jump onto the golf course was Captain Logan W. Hovis, the surgeon of the 3rd Battalion, who was in the first stick of the second plane. Although Hovis landed safely in the center of the golf course, the strong winds caught hold of his parachute canopy before he could collapse it and dragged his slight 120-pound body across the course. Though he could have tried to grab onto something or cut himself free of the harness, he “did not want to risk injuring his hands.” In time, his canopy snagged on a shattered tree but Doc Hovis had become so entangled in his parachute lines that he could not move. Eventually, 1st Lt. William D. Ziler found him and cut him out of his cocoon.

As it turned out, Doc Hovis’s expert hands would find more than enough work throughout the next few days. The other 3rd Battalion surgeon, Captain Robert R. McKnight, severely fractured an ankle upon landing and was pinned down by enemy fire for some time behind a fallen tree. After rescue, the injured McKnight was evacuated from Corregidor.

The strong winds blew 25 paratroopers from Company I past the golf course and about 300 yards to the southeast, off Topside and 200 feet down the cliff face near a small promontory named Breakwater Point. Scrambling out of their parachute harnesses, the men collected together and were following a narrow trail back up to the top when they spotted eight or nine Japanese soldiers apparently watching the maneuvers of the landing craft of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment coming around the west end of Corregidor to attack the south shore.

Springing into action, the I Company paratroopers fired their rifles and threw hand grenades at the Japanese assemblage. Unknowingly, they had just killed the Japanese commander on Corregidor, Captain Akira Itagaki, who had failed to fortify Topside against airborne assault on the belief that such an attack was impossible.

Taking Enemy Fire

After the first few dozen transport planes made their first pass over both the parade ground and the golf course, they began taking ground fire from the Japanese. Although taken completely by surprise by the airborne assault, the Japanese were quick to respond. Now, in addition to the jumble of jagged debris below them, the paratroopers had to worry about incoming fire from the aroused Japanese garrison on Corregidor.

Although the drop zone at the parade ground was less than ideal, one gun crew from Battery A, 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion got lucky. “We were most fortunate in our jump,” Pfc. James Wilcox recalled. “Our equipment landed in the exact center of the drop zone…. The net result was that our section had its gun assembled and at our rendezvous point hours before the next section arrived. The other two sections had been jumped off the top of the island, some even into the sea, and didn’t get there at all.”

Colonel Jones recalled the story of the missing artillery sections. “One artillery battery [sic] … landed on the hillside near the water. They found it [more] convenient to walk to the water’s edge and get picked up by a PT boat which was standing by to take care of any water landing emergencies and actually came in over the beach in good style.”

The commanding officer of the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, Major Arlis E. Kline, had a most memorable descent. “I was dropping towards Landing Zone A [the parade ground] when I was hit by an unidentified piece of flying steel,” he stated. “My arm was so badly wounded I could not control my chute as I passed towards the last few houses along Officers Row.” Barely missing becoming impaled on a jagged tree trunk but suffering serious leg injuries, Kline ended up hanging in a tree, with his feet touching the ground but unable to stand and release his harness. For a time, he lapsed in and out of consciousness until one of the men that had followed him out of the aircraft cut him down.

Two Silver Stars

Another member of the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion was Captain Emmet R. Spicer, a doctor. The award for his posthumous Silver Star read in part: “Upon landing by parachute, Captain Spicer immediately organized his aid station and then proceeded under heavy enemy machine gun, sniper and mortar fire towards Wheeler Battery, attempting to evacuate the many wounded personnel to the aid station. He was fully aware of the personal risk involved and was repeatedly advised against going into this dangerous area. Stating that it was his duty to minister aid to the wounded despite the attendant danger, he proceeded at once toward the enemy-infested area. He paused several times en route to aid injured and wounded soldiers, ministering to them while still under a hail of enemy bullets. His performance of duty in complete disregard to his own safety was far above that normally required or expected and in the execution of them he gave his own life.”

When Doc Spicer’s body was recovered, it was noticed that he had filled out his own emergency medical tag. Written below his name, rank, and serial number, the doctor had entered the following under “Injury”: “GSW [gunshot wound].” Under “Prognosis” he had entered “Death.”

Another trooper to win the Silver Star was Sergeant John A. Hanson (3rd Battalion, Headquarters Company). Landing safely atop Topside, he immediately realized that three bundles containing 81mm mortar rounds were missing. “Realizing the urgency for their need,” stated his Silver Star citation, “he immediately began a search for them.” Finding that they had drifted over the cliff and landed in a ravine near the entrance of several enemy-occupied caves, Sergeant Hanson, “although fully aware of the enemy situation and the danger involved,” did not hesitate to climb down the ravine to recover the ammo. Although immediately coming under fire, he reached the bundles and carried the ammunition “piece by piece up the torturous incline to the top. Although near exhaustion and still under enemy fire, he did not stop until the mortars were put in action.” The mortar rounds that Sergeant Hanson retrieved were later used to silence a Japanese antiaircraft gun “which threatened personnel jumping in later echelons.”

Colonel Jones’ “Rock Force”

At 9:40 am, with most of the C-47s having circled three or four times to empty their loads, Colonel Jones decided to leave his own C-47 and join his men on The Rock. In quick succession, he and his orderly jumped from the control plane. “We landed in a sheared-off tree area short of the parade ground, which was our target for landing. A four- or five-inch tree stump took the flesh off the inside of my thighs on each leg, which was somewhat painful, but did not require any attention from the medics…. At any rate, my orderly sustained a broken ankle, but we moved to Topside….”

By 9:50 am, all of the men were down and the C-47s and escort planes were winging their way back to Mindoro to pick up their second sticks. The island of Corregidor was still taking a pounding from warships and aircraft as the landing barges carrying the 3rd Battalion of the 34th Infantry Regiment neared the landing beach at San Jose. By 10 am, in spite of his injury and the steady rain of incoming fire, Colonel Jones had his regimental combat team set up in a devastated Mile-Long Barracks building on the north side of the parade ground. With Jones landing on Corregidor, the attacking forces, both paratroopers and infantry, now became part of “Rock Force” under his overall command. He now had sole control over every American combatant on Corregidor.

By the time the command post was set up, the 3rd Battalion, 503rd PRCT found some opposition from pillboxes developing along the slopes. The Japanese, members of the Manila Bay Entrance Force who had sought shelter from the preinvasion bombardment, were now fully aware of the assault from above and were filtering through the caves and ravines cut inside Topside and Malinta Hill to fight back at the invaders. And, instead of only 900 Japanese soldiers there was actually close to 6,000, with approximately 3,000 positioned to defend Topside and the other 3,000 concentrated in the Malinta Hill and Tunnel areas. Since most of the Japanese forces had been set up to repel an amphibious invasion, it had taken a little while to respond to the attack from above.

Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese communication center was located on Topside, far from the suspected invasion beaches, and was captured within the first hour of battle. That coup along with the quick killing of Captain Itagaki left the Corregidor defenders without a head or nervous system to control the rest of the body.

16 Percent Jump Casualties

By 10 am, most of the paratroopers of Companies G, H, and I and the artillery pieces and heavy machine guns of Batteries A and D had assembled and had secured the two landing zones. Only one plane, carrying a stick of demolition men, had been forced to abandon the drop because of engine trouble. Squads of men were beginning to spread out from the drop zones, trying to clear the demolished structures that had suddenly become havens for Japanese snipers. Company G, under the command of Captain Jean P. Doerr, captured and secured the area around Ramsey Ravine, south of and overlooking the left flank of the American amphibious assault. Two .50-caliber machine guns from Battery D, 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion were placed atop the ravine and provided heavy covering fire for the waterborne invasion of the 24th Infantry Division.

At 10:28 am, the first landing craft carrying the infantrymen touched shore at Black Beach near San Jose, on the south side of the tadpole’s neck. Surprisingly, opposition was light against the first four waves, and the foot soldiers pushed quickly inland, reaching the top of Malinta Hill by 11 am. After that, the infantry and vehicles along the beach began to take heavy fire as the Japanese shook off their preinvasion pounding.

Around 10:30 am, while the 34th Infantry Regiment troops were landing, the wind began to increase on Topside. After this discovery and determining that he had 161 jump casualties, including nine people from his medical staff and 13 from the field artillery, Colonel Jones had some doubt about allowing the second jump to take place. While he could have had his 2nd Battalion paratroopers flown to Mariveles on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula and brought over to Corregidor by landing craft, that action would have left the 3rd Battalion on top of The Rock all by itself—already with about 16 percent casualties. However, when communication with Mindoro could not be established the decision on whether to let the 2nd Battalion jump or not became a moot point. The paratroopers were going to jump.

“There it is!”

Back on Mindoro, the 2nd Battalion was awakened at 7:30 am and given a leisurely breakfast. After gathering up their gear, including their weapons and Mae West life vests, they loaded onto the trucks, and beginning around 9:30, were taken to Hill and Elmore airstrips. “We got to the strip about 10:30 as the planes were coming in from delivering the 3rd Battalion,” recalled 1st Lt. William T. Calhoun (Co. F). “We could see bullet holes in some of them, so we knew that they had drawn fire. Our plane, No. 23, came in, and we started getting our equipment ready. The pilot told me a lot of jumpers were blown over the cliffs….”

The men from Company E, along with six planeloads of men from 2nd Battalion Headquarters and Headquarters Company, the guns and men of Battery B, and machine guns and men from Battery D, were slated to drop on the parade ground. The men from Companies D and F along with three planeloads of men from Headquarters and Headquarters Company, were scheduled to drop on the golf course.

The 50 C-47s began taking off around 11 am. Once all of the planes were airborne, the flight, which was once again protected by squadrons of P-38 and P-47 fighters, headed toward Luzon. By 12:30 pm, Corregidor was in view.

“Suddenly [Technical Sergeant Philip] Todd [Co. F] said, ‘There it is!’” continued Lieutenant Calhoun. “I saw bare, white cliffs rising out of the sea, coming out from under our left wing. Then I could see Topside and chutes strung all the way from the sea, up the cliffs and on ‘A’ and ‘B’ Fields. We could hear small arms fire, both rifles and machine guns. I first thought it was all fights on the ground then a bullet crashed through the plane and I said, ‘Oh! Oh!’”

Major Lawson Caskey, the 2nd Battalion commander, was the first man from the second lift to jump, leaving his C-47 over the parade ground at 12:40 pm, 25 minutes behind schedule. By now, all of the C-47 pilots knew that they had to stay at about 400 feet altitude, and the jumpmasters knew that there was a 25 mile per hour wind blowing to the east. At the same time, the Japanese were more alert when the second lift arrived, opening fire with antiaircraft guns, especially from Battery Wheeler in the direct flight path of the parade ground planes and from Battery Cheney a little farther north along the west coast.

Edward Gulsvick’s Bravery on the Parade Grounds

The commander of Company E, Captain Hudson C. Hill, was the first man out of his plane at 12:44 pm. After the plane passed over the parade ground, he waited the recommended seven seconds and then jumped. “I landed in the ruins of a concrete building,” he remembered. “The building was three floors high. Upon hitting the top of the building my parachute collapsed and I tumbled through the ruins to the ground floor. The only serious result of the fall was to have seven teeth knocked out or broken off. The loss of the seven teeth was a fair exchange for possible death had I landed outside the building. The ground outside the building was being swept with intense enemy machine-gun fire from pillboxes….”

With blood streaming from his mouth, Captain Hill discarded his parachute and harness and surveyed the situation. Eventually, about 50 men from Company E landed in or around the ruined building he was in and became trapped by machine-gun crossfire coming from Batteries Wheeler and Cheney. At both batteries, the Japanese had managed to retrieve a couple of .50-caliber American machine guns and ammunition that had been misdropped by the first lift and were now firing them at the invading paratroopers of the second lift.

“Several men could be [seen] attempting to free themselves from their parachute harnesses and avoid the heavy enemy fire,” Hill continued. “Several of the men in the area did not move, they were still in their harnesses, and very evidently would never know what hit them.”

While floating down into the area south and west of the parade ground, Staff Sergeant Edward Gulsvick, the platoon sergeant for Company E’s 60mm mortar platoon, was hit and severely wounded by Japanese fire. Upon landing, he saw that several Japanese were attempting to “spear the jumpers on their bayonets as they landed.”

Although already wounded and in an exposed position, Gulsvick opened up with his Thompson submachine gun and killed 14 Japanese soldiers singlehandedly. Ignoring his severe wounds, Sergeant Gulsvick attempted to drag a fellow paratrooper to safety but was hit and killed by simultaneous bursts from Japanese machine guns near Batteries Wheeler and Cheney. For his unselfish act of heroism, Sergeant Gulsvick received a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

Another Round of Paratroopers at the Golf Course

The men from Company F jumped over the golf course and caught as much enemy fire as the men jumping onto the parade ground. Lieutenant Edward T. Flash, commander of F Company’s 2nd Platoon, recalled, “Our aircraft made three passes, extremely low, dropping approximately three troopers each pass. Each time we passed over the golf course the floor of the aircraft was riddled with bullets, splinters flying everywhere. Three men were wounded in the legs on the first pass. Two men insisted on jumping, but the third man was bleeding profusely and had to return with the aircraft to Mindoro.”

After hitting the ground, 20-year-old Private Lloyd G. McCarter caught sight of a Japanese machine-gun nest that was spraying his Company F comrades as they touched down on the golf course. Disregarding his own safety, he raced across 30 yards of open ground under intense enemy fire, emptying his Thompson submachine gun and tossing hand grenades toward the nest. When only a few yards away, a well thrown grenade landed in the midst of the Japanese position and silenced the gun forever.

Private First Class Richard A. Lampman was in another Company F plane. “I remember being four or five in the stick,” he wrote, “and when I landed helped a trooper that had one of those sharp pointed trees in his leg all the way through. He could not stand or lay [sic] down. I managed to break it so he could lay flat on the ground. I also helped one of the ‘old timers’ who had broken his ankle. This was Acting Sergeant James Wright…. The wind was blowing their chutes and I was afraid they would become more seriously wounded or killed.”

“Each artillery battery dropped six 75mm pack howitzers as we did not know what our losses would be,” commented Captain Henry W. Gibson, commanding officer of Battery B, 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. “My men recovered all six of our howitzers plus two of A Battery’s. I headed for battalion headquarters in the old barracks to report to the battalion commanding officer. When I got there, I found Major [Arlis] Kline [the commanding officer] on a stretcher with his head all bandaged and his arms in slings.” Kline had been wounded in the arm while descending and had sustained further injury when he landed in a tree.

Lieutenant Calhoun, who jumped over the golf course, recalled, “The wind was strong. I sure did want to get this landing over, and I did in a hurry. From the low altitude jump we were not in the air long. I went down into a large crater, slammed into its rocky side with my right side splintering the stock of my M1 rifle. It knocked the breath out of me and I thought broke some ribs. I did not breathe easy for days…. Although shaken I was very glad to be down on the ground safely and without injury.”

Around 1:20 pm, while some of the 2nd Battalion paratroopers were still landing, there was a steady increase in sniper and heavy machine-gun fire from the east. West of the golf course, Captain Hill and the 50 men from Company F still trapped inside one of the Mile-Long Barracks buildings finally managed to contact their executive officer and call in an artillery strike on the enemy gun emplacements that had them pinned down since landing.

Remembered Captain Hill, “When the welcome sound of the 75mm pack howitzer was heard … the fire from the pillboxes abruptly ceased.”

By 1:30 pm, about an hour after the 2nd Battalion began its combat parachute drop, everybody was on the ground. Although numerous medical bundles had been lost or remained unclaimed, the battalion and regimental aid stations had been set up and the uninjured doctors were doing all that they could for the injured and wounded. At 2:00, Colonel Erickson directed naval gunfire against some pesky Japanese pillboxes that were holding up the advance of his 3rd Battalion troopers.

The Flag Flies High Over The Rock

By 3 pm, the Americans were firmly in possession of the high ground of Topside. Both the 2nd Battalion and RCT Headquarters had their command centers set up in the barracks buildings just north of the parade ground, while 3rd Battalion Headquarters was set up in a lighthouse just north of the golf course. The 2nd Battalion had relieved 3rd Battalion of the job of holding the drop zones and had established a perimeter with Company E to the north and northeast, including the hospital and more barracks buildings. Company D held a position along the east and southeast flank while Company F established a line to the west. The 1st Platoon of Company I, although part of the 3rd Battalion, was kept in place on the southwest side of the perimeter, facing dangerous Battery Wheeler and a steep ravine, where 24 Japanese soldiers had already been killed.

Once relieved, the 3rd Battalion had headed northeast on Topside, hoping to grab positions to aid the infantrymen of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment and establish contact with the men on Malinta Hill. Company G traveled the farthest east and held a spot overlooking San Jose and the landing beaches, controlling the route leading down to Bottomside. Company H went northeast and established a perimeter behind an antiaircraft emplacement known as Battery Chicago, which they had captured from behind, and the last two platoons of Company I held the high ground overlooking Ramsey Ravine, just southwest of San Jose.

At 3:10 pm, as if to punctuate the fact that the 503rd PRCT was there to stay, T/5 Frank Guy Arrigo and Pfc. Clyde Bates shinnied up the tall Corregidor flagpole at the parade ground under sniper fire and raised the American flag over The Rock for the first time in almost three years. The singular sight of that flag helped boost the morale of everyone who saw it.

Assessing Casualties

Near nightfall, Companies G, H, and I were pulled back from their outside positions and into a tighter perimeter. Although sporadic fire continued throughout the night, most of the fighting on February 16 was over. The second jump onto Topside had been less destructive than the first, mainly because the pilots and jumpmasters had learned from the mistakes of the first drop. The total jump injuries sustained during the second drop was somewhere around 50. Combined with the 161 injuries of the first drop and several listed as “Later Reported,” the combined total for both jumps was 222 injuries. Since 2,050 men from the 503rd jumped on Corregidor on February 16, jump casualties amounted to a loss of 10.8 percent, much less than the 20-50 percent that had been feared.

In addition to the 222 jump casualties, the 503rd PRCT also had 50 men wounded in their parachutes while descending or shot on the ground while still in their chutes. However, the entire regimental combat team suffered only 21 deaths. Three men had parachute malfunctions, with one man landing in the bottom of the empty Topside swimming pool. Another two were killed when they slammed into concrete buildings as they landed. Fifteen were killed by Japanese fire after becoming entangled in their chutes. The cause of death for the last man is not stipulated. In all, by the end of February 16, 1945, the 503rd PRCT had been deprived of the services of 293 men from all units, a total loss of 14.2 percent.

At 8:30 am on February 17, another 44 C-47 transport planes carrying Major Robert H. Woods’s 1st Battalion paratroopers from the Mindoro airstrips passed over Corregidor. Lieutenant Calhoun, already on Topside, wrote, “Expecting to welcome the arrival of the 1st Battalion, many of the 2d and 3d Battalion men on the ground were surprised when the only parachutes to fall from the aircraft were those of the equipment bundles. Word had not filtered down to all ranks that it had been decided that Topside was sufficiently secure that there was no need to suffer unnecessary jump casualties on the dangerous and undersized landing zones.”

During the night, after studying the available information, and still working under the assumption that Corregidor was inhabited by no more than 900 Japanese soldiers, Colonel Jones had made the decision to bring the 1st Battalion in by landing craft.

“A Large Scale Mop-Up”

While the planes were passing over the island and the air crews were shoving out the equipment bundles, the Japanese opened up with a heavy barrage of antiaircraft fire. Noted Lieutenant Calhoun, “It is just as well [that the third jump was not made], for whilst Topside may have been considered by Rock Force HQ to be secure, the ravines surrounding it were most definitely not. It was from the ravines that numerous streams of small arms fire arced upwards towards the fully-laden aircraft as they slowed overhead to drop their bundles. Sixteen of the aircraft received fresh holes from hits. Several men, principally airmen, were wounded by this ground fire.”

Flown to San Marcelino Airfield above the Bataan Peninsula, the 1st Battalion paratroopers were eventually placed aboard landing craft and brought to Corregidor’s Black Beach at 4:35 pm.

“Once Rock Force was ashore,” wrote historian Smith, “operations on Corregidor evolved into a large scale mop-up.” Rock Force developed a pattern to eliminate the Japanese.

Noted Colonel Jones, “During the period from 16 February to 23 February our systematic destruction of the enemy fell into a familiar and an extremely effective pattern; direct fire of artillery used as assault weapons on enemy emplacements, naval and/or air bombardment followed by immediate ground attack…. In proportion, enemy casualties far exceeded ours.”

Private Lloyd McCarter’s Medal of Honor

On the afternoon of February 18, while the paratroopers were still consolidating their positions, Private Lloyd McCarter, who had singlehandedly attacked a Japanese machine-gun position five minutes after landing on The Rock, killed six Japanese snipers that had been firing at members of his Company F. In order to figure out where the deadly fire was coming from, McCarter had stood up, drawn the snipers’ fire, and then in turn calmly shot down each man.

During the predawn hours of February 19, the Japanese launched a banzai attack, costing them more than 400 men. Private McCarter was instrumental in throwing back this attack. On the evening of February 18, McCarter had spotted Japanese troops trying to outflank the Company F perimeter and had voluntarily moved into an exposed position so that he could better see the enemy and pick them off with his Thompson submachine gun.

Throughout the night, the Japanese continued to attack his position, but McCarter never wavered, killing each man that came close to his spot. By 2 am on February 19, all of the other paratroopers close to McCarter had been wounded, but the plucky private carried on. When McCarter ran out of ammunition, he crawled back to the Company F perimeter, loaded himself up, and went out again. When his Thompson submachine gun grew so hot that it would no longer fire, he discarded the useless weapon and grabbed a BAR from the hands of a dead paratrooper. When that weapon also overheated, he threw that aside and snatched up an M1 rifle from another dead trooper.

At 6 am, when the Japanese staged their banzai charge, the pile of dead Japanese bodies was so high in front of Private McCarter’s forward position that he had to stand up to see the enemy and get off clean shots. While standing erect behind this mountain of dead Japanese, McCarter was shot squarely in the chest, which finally knocked him to the ground. When a medic crawled forward to pull McCarter to safety, the young private refused, insisting that he had to stay put to warn his companions of the approaching enemy. A few minutes later, however, he collapsed from loss of blood and the medic finally pulled him inside the Company F perimeter.

Although seriously wounded, McCarter did not die. By himself, McCarter had killed more than 30 Japanese soldiers and had helped his company in killing dozens more. Eventually taken off of Corregidor and sent to an Army hospital, he was still recovering from his chest wound several months later when was asked to come to the White House so that President Harry S. Truman could personally present him with the Medal of Honor. It was the only Medal of Honor given to any American fighting man on Corregidor.

Blowing Up the Arsenals

Over the next few days following the banzai charge, the Japanese committed destructive suicide by blowing up underground ammunition and fuel dumps, usually after being cornered by American troops, who were also injured by the explosions. On the night of February 21-22, the Japanese exploded the vast amount of ammunition and explosives stored inside Malinta Tunnel. By 6 pm on February 23, Colonel Jones was able to declare that Topside was secure.

On February 24, the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 503rd PRCT began attacking eastward along the tail of Corregidor while the 2nd Battalion stayed atop Topside and the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment dug out the last Japanese defenders on Malinta Hill. Although the paratroopers faced a few banzai charges, they kept advancing and by February 26 were near Monkey Point, only 2,000 yards from the tip of Corregidor’s pointed tail.

Shortly after 11 am on February 26, the Japanese exploded an underground arsenal near Monkey Point in what historian Smith called a “suicidal tour de force.” The tremendous explosion caused 196 American casualties, including 52 killed. A Sherman tank, which had stopped near the vicinity of the main charge, was blown end over end for hundreds of feet. Debris from the explosion hit a destroyer 2,000 yards offshore, and a man standing on Topside, almost a mile away, was hit by flying rocks. Many of the men killed and injured in the explosion were paratroopers belonging to the 1st Battalion, 503rd PRCT.

“Sir, I Present to You Fortress Corregidor.”

By 4 pm on February 26, the paratroopers reached the far eastern tip of Corregidor. Except for a little mopping up, the battle was over. On March 2, General MacArthur returned to The Rock and replaced the battletorn flag of the 503rd PRCT with a brand new American flag. During the flag-raising ceremony, Colonel Jones stepped forward, saluted General MacArthur, and said, “Sir, I present to you Fortress Corregidor.”

The 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team had 17 officers and 148 enlisted men killed on Corregidor. It also had 17 officers and 267 enlisted men wounded, 64 sick paratroopers evacuated, and 331 troopers listed as injured for a total of 844 casualties. Out of a total force of 2,962 paratroopers, engineers, artillerymen, and other personnel, the 503rd PRCT suffered casualties of 28.5 percent.

The reinforced 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division had 264 casualties out of 1,598 men. Overall, Rock Force suffered 1,105 casualties out of 4,560 men, a loss of 24.3 percent. The Japanese, who fought to the bitter end, had almost 100 percent casualties. Only 20 Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner. Among the men killed were 200 soldiers that tried to swim to the Bataan Peninsula but were intercepted by the surrounding U.S. Navy ships.

In 1942, it had taken the Japanese five months to conquer the 1,300 American defenders on Corregidor. In 1945, it took Rock Force 15 days against 6,000 defenders to take it back.

A family friend, A.T. Taylor of Texas, served in Co H, 3rd Battalion and made the jump on Corregidor February 16th, 1945. He injured his ankle on landing and was later evacuated. We first met A.T. Taylor and wife Tis shortly after the War, in Houston, Texas…when they rented an adjacent apartment. The Taylor’s later moved to Quitman, Texas and started a farm. My parents kept in contact with the Taylor’s for many years and visited them on several occasions. I visited A.T. Taylor in 1986, and he gave me an autographed copy of “Three Winds of Death” by Bennett M. Guthrie. It is a praised possession in my library. They have all passed into history now….part of the “Greatest Generation”.

My dad, William T. (Bill) Calhoun was a proud 503rd paratrooper. He felt such pride that the 503rd had been chosen to retake The Rock. I have heard him say SO many times: “that was our island fortress”. He could not believe they had been chosen for such a noble fight! Bill Calhoun, F Company, 2nd Battalion

Great article these guys are great heroes

An extraordinary story, very well told.

Thank you.

Not sure of his first name. But a man named COUNTS who retired in Center, TX was on this jump. At 88 Mr. Counts could still wear his uniform.

Thank for a wonderful story. You mentioned my uncle Major Arlis Kline who was severely wounded. He survived his injuries and after the war become a doctor himself. A veterinarian. For many year, he ran his own pet hospital in Huntington Beach California. Then he retired to New Zealand. He passed away in 2012 at the age of 93.

Excellent article. Many authors use the term “won” in relation to medals. It’s not a competition, they are awarded medals. Had a chat with a MOH holder and he hated the term “medal winner”.

Great article. My dad was a signalman on the USS Crosby, APD 17. He was on one of the landing boats that got pinned down when they brought the 1st Battalion in. A paratrooper was hit and, as he gave him first aid, he strung the troopers field glasses and carbine over his neck. They eventually had to get up and run for the LCI’s that were beached and, as he ran, my dad thought he was getting hit. I turned out the glasses and carbine were bouncing off his chest. I still have the field glasses.

The article needs to be corrected. 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry landed on Corregidor and replaced 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment (they had to report back to the 24th Inf Div for another operation) on February 24th and completed mop up operations with the 503rd. Once those operations were completed, 151st took over the island until they were sent to capture other islands in the area. The 151st Inf suffered several casualties on Corregidor and it should be recognized.