By Arnold Blumberg

A stark dichotomy was evident among the Americans defending Breed’s Hill on June 17, 1775. One type of provincial soldier stood ready to give his life in defense of liberty that day. These men manned the rail fences, stone walls, and the redoubt on Breed’s Hill awaiting the British attack. They listened intently to the orders of their officers. They were determined to endure the fiery test of battle once the British began their advance.

The other type of provincial soldier was the shameless coward who did everything in his power to avoid the fight that was brewing that day. These shirkers hid behind trees, rocks, and haystacks. Even as the storm of battle was about to break, they were seen in full retreat from the battlefield. They said the battle was lost before it started and blamed their bad fortune on the lack of artillery, shortage of good officers, and other excuses.

But the story of the Battle of Bunker Hill is about the deeds of the former rather than the failings of the latter. The Americans were well entrenched by the time the British were ready to advance at mid-afternoon on June 17. On the American right, Massachusetts farmer Colonel William Prescott spoke words of encouragement to his inexperienced troops. He told them that the redcoats would never reach the redoubt if they followed his directions. He ordered them to hold their fire until he gave the order.

As for the troops on the American left, New Hampshire native Colonel John Stark advised them to make every shot count. Each man had only 15 rounds and scant gunpowder. Stark told the men not to fire until the redcoats had passed a stake that he had planted 35 yards in front of their position. Furthermore, he advised that they should hold their fire until they “could see the enemy’s half-gaiters.”

As both sides waited anxiously for the battle to begin, the town of Charleston on the British left flank erupted in flames. British Admiral Samuel Graves had not only ordered incendiaries fired into the town from British warships, but also ordered a detachment of sailors to go ashore and make sure that the town burned to the ground. The gunfire from the warships sent a Patriot detachment in the town scurrying west toward the main American line.

While the flames licked skyward, Maj. Gen. William Howe addressed his troops just before he ordered a general advance. “I shall not desire one of you to go a step farther than where I go myself at your head,” he said. Howe thought that his men would be able to cover the distance from Morton’s Hill to Breed’s Hill quickly, but he had not reconnoitered the ground over which he would be attacking. The undulating ground was studded with rocks and laced with gulleys that would disrupt the alignment of the British lines. Furthermore, the British would have to climb over several stone walls. The British stepped off at 3 pm. They initially were unaware that the Americans were behind breastworks, but as they drew closer they saw that the Americans held a strong position.

Howe marched smartly at the head of his imposing grenadiers toward the American left. To his right marched Lt. Col. George Clark’s Light Battalion. Howe’s staff, as well as a servant carrying a bottle of wine, accompanied him. The British guns fell silent so as not to injure their own soldiers.

As Clark’s troops passed Stark’s stakes, they lowered their 17-inch-long bayonets and charged. “Fire!” Stark shouted. A sheet of flame erupted from behind the stone wall. The British line staggered under the well-aimed volley. The front rank of the Light Company of the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers crumpled to the ground. In the second line, the Light Company of the 4th King’s Own Regiment of Foot was decimated as it struggled to push forward. Many men belonging to the 10th and 52nd Regiments fell dead and dying on the beach on the Americans’ extreme left flank. Minutes after being struck by the American fire, the English light forces turned and fled. They left behind 96 dead and dying men. Howe’s attempt to turn the enemy’s weakest point had failed.

As the light infantry decamped for the rear, the British grenadier companies approached a rail fence. By that point, their well-aligned formation had deteriorated. They had become a disordered mass. They fired one volley and then charged with their bayonets. The lead from their volley flew harmlessly over the heads of the crouching Patriots.

Prescott’s troops opened fire on the British at 50 yards. The volley devastated the unprotected British line, cutting deep furrows in the grenadiers’ ranks. Howe pulled his shocked and battered men back to regroup. He had no intention of giving up or altering his basic plan of attack.

Following the disastrous British raid on American arms and powder supplies at Concord on April 19, 1775, the British withdrew to Boston to plot their next move. It fell to Maj. Gen. Artemas Ward, who was the senior general present at Boston, to organize the provincial militia of Massachusetts and adjacent colonies and keep the British bottled up in Boston until Continental Army Commander in Chief General George Washington arrived.

Ward, who suffered from extremely poor health that often forced him to rest in bed, had the formidable task of organizing upward of 10,000 volunteers who were present for duty at Cambridge and would become the Army of Observation. A Massachusetts native, Ward initially had no power to enlist, pay, or arm the troops, but on April 24 the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized the regular enlistment of an army to be composed of regiments of 10 companies each. Enlistments were to run until the end of the year.

While Massachusetts went about organizing a force to defend its cities, towns, villages, and farms, the other New England colonies raised their own forces. The New Hampshire General Assembly voted on May 18 to form the New Hampshire Volunteers under Colonel John Stark, a veteran of the French and Indian War and a member of the famed Roger’s Rangers. As for Rhode Island, its assembly had established three regiments and an artillery company under the newly promoted Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Greene. The Connecticut Assembly on April 26 raised six infantry regiments, a total of 6,000 men, to serve until December 10, 1775. Two of these formations were sent to Cambridge where they were commanded by Brig. Gen. Israel Putnam of the Connecticut militia.

By early June 1775, the Patriots had assembled a sizable force outside Boston. The Patriot army effectively blockaded the city and its British garrison. The British at Boston were led by Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, the commander in chief of the British Army in North America.

Gage had extensive experience in North America dating back to the French and Indian War. He later served as commander in chief of the British forces in North America from 1763 to 1775. While serving as military governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, he had earned the animosity of the colonists for his role in applying the Intolerable Acts.

Gage’s attempt to seize military stores of Patriot militias in April 1775 touched off the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Of medium height and slender build, Gage had a sober nature. He was a nondescript battlefield commander. He exhibited more ability as a politician than a general.

Keenly aware of the growing opposing force surrounding him, Gage, exhibiting a cautious trait he had been criticized for during some of his past military dealings, believed his 3,000 troops at Boston were insufficient to make any offensive move against the mounting Patriot threat. Another 1,500 reinforcements were expected in May, so Gage decided to await their arrival. The result was a stalemate.

On the American side, the Rebel leaders became aggressive as their forces grew. On May 9, Ward ordered the fortification of Dorchester Heights. Maj. Gen. John Thomas blocked Ward’s sound military idea. Thomas, who was trained as a surgeon, had served as a militia colonel during the French and Indian War. In February 1775 he had been appointed a brigadier of the Massachusetts militia. Thomas had taken command of all troops stationed at Roxbury, which was situated southwest of Boston, following the clash at Lexington. Although nominally under Ward, Thomas acted as if his force was an independent army. For this reason, he refused to obey any of Ward’s directives.

The two opposing armies engaged in a series of raids on the tightly packed islands in Boston Harbor in May in an attempt to grab as much of the food stores and livestock as possible. On May 21 Gage sent four British sloops-of-war to harvest the hay from Grape Island. Responding to the enemy move, the Weymouth Minutemen and three companies from Thomas’s force at Roxbury chased off the sailors and marines landed by the British warships.

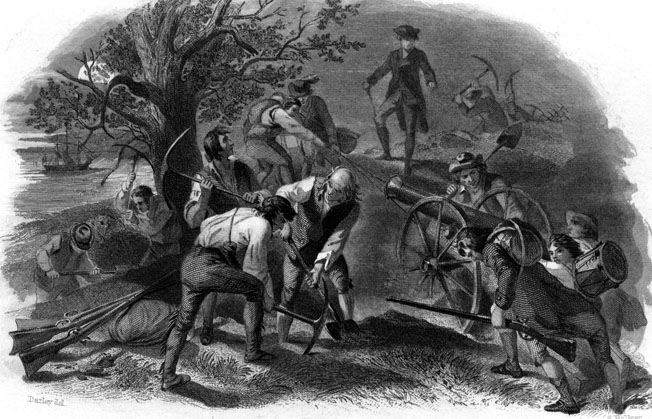

The most significant skirmish of this period occurred on May 27. Stark, who commanded the 1st New Hampshire Regiment, and Colonel John Nixon, commander of the 6th Massachusetts Regiment, led 600 men to Hog Island and Noddle’s Island, which were situated next to each other directly northeast of Boston. Their mission was to remove livestock from farms on the two islands.

Graves issued orders for a force of 400 Royal Marines to land and engage the Americans on Noddle’s Island. Fired upon by the British, the Americans fell back to Hog Island. Putnam had arrived on Hog Island with 300 men, and the two forces joined together to defend a makeshift entrenched position built in a marshy ditch. The Patriots, who were supported by several 3-pounder guns, fought the British to a stalemate over the course of seven hours. The heavy guns of the British warships failed to dislodge the Americans.

During the fighting the British schooner Diana ran aground, and the Americans fired upon it with their artillery. Unable to dislodge the Diana, the British abandoned it. Having found the American position too strong to carry, the marines withdrew. The Battle of Chelsea Creek, as the affair was called, ended in an American victory.

The British attempted another raid on May 28 against Hog Island near the Winnisimmet Ferry crossing. The Americans were waiting, though, and repulsed the Royal Marines. When American artillery demolished a British barge, the battle came to a speedy conclusion. The British withdrew to Boston, and the Americans retained control of the islands.

American casualties from the island skirmishes amounted to one killed and three wounded, while the British suffered 20 killed and 50 wounded in addition to the loss of a schooner and two barges. Further American raids on Noddle’s and Paddocks Islands on May 30 and May 31, respectively, netted additional livestock. By keeping the island livestock out of British hands, the Americans denied their foe desperately needed sustenance.

The island skirmishes also revealed important traits of some of the opposing combat leaders. Stark proved to be a formidable leader of men. He handled his troops well on both attack and defense. As for Putnam, he showed that he still had fire in his belly when it came to a pitched fight. On the British side, Graves exercised too much caution with the ships he commanded. He was reluctant to expose his warships to the hazards of combat. The head of the British Navy in North America since mid-1774, he did not get along with Gage. The admiral, who was known for his incompetence and corruption, failed to use his overwhelming naval superiority to protect the Boston Harbor islands and the vital supplies they held during the spring of 1776.

In early May, the remaining companies of the British Army’s 65th Regiment of Foot and a second battalion of Royal Marines arrived from Halifax. Then, more reinforcements arrived in late May from Ireland. These troops were the 35th, 49th, and 63rd Regiments of Foot and the 17th Light Dragoon Regiment. With the substantial reinforcements he received, Gage’s army of occupation in Boston swelled to 6,500 men.

On May 25 three British major generals—Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton disembarked from the Cerberusat Boston Harbor to assist Gage. Tall, handsome, and well mannered, Howe had served in North America during the French and Indian War, participating in the Louisburg expedition and the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. A gifted tactician with a commanding presence on the battlefield, he had championed the use of light infantry as an essential element of the British Army. As for the assertive and self-promoting Clinton, he had served on the European continent during the Seven Years War. Burgoyne, the most junior and least experienced of the generals sent to Gage, had served in Portugal during the Seven Years War.

Both Clinton and Burgoyne were bothered by the inactivity of the British Army at Boston. Encouraged by the two aggressive newcomers, Gage held a council of war on June 12. As an outgrowth of the council of war, Gage decided to extend a final offer of general pardon to all rebels provided they agreed to immediately lay down their arms. Because he did not expect the rebels to accept their proposal, Gage ordered his generals to draw up plans to seize Dorchester Heights and Charleston Neck in a operation set to begin June 18.

The Americans learned of Gage’s plan through their robust spy network. They had about 10,000 troops in the Boston area by mid-June. To counter the British operation, on June 16 Ward ordered Colonel William Prescott of Massachusetts to take 1,000 men and supporting artillery to entrench on Dorchester Heights and Bunker Hill. Prescott, a veteran of the French and Indian War, was known for his unhurried movements and coolness in times of danger, was one of the more aggressive of Ward’s subordinates. Captain Thomas Knowlton, who commanded the 5th Connecticut Regiment, reinforced Prescott with 200 Connecticut soldiers. Although they asked General Thomas if he desired to participate in the operation, he declined the offer.

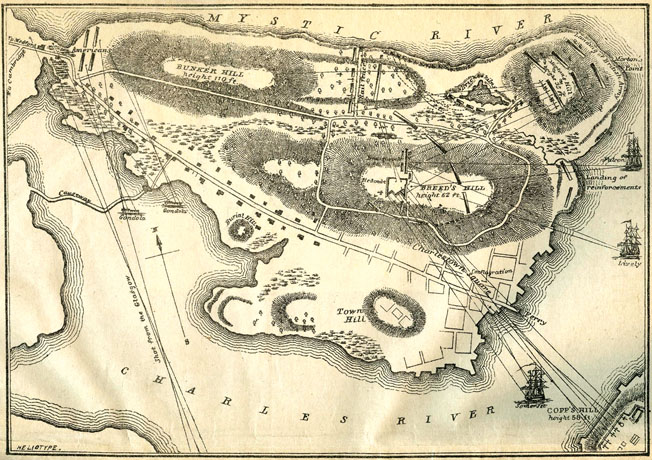

Charlestown Peninsula, which was situated across the Charles River from Boston, was a mile long and a half mile wide. Bunker Hill is located on the northern end of the peninsula, Breed’s Hill in the center, and Morton’s Hill on the southeastern corner. Bunker Hill is slightly higher than Breed’s Hill. A narrow point in the northeastern sector known as the Neck, connects Charlestown Peninsula with the mainland. Most of the peninsula was open ground, except for the buildings of Charlestown.

After crossing the Neck, Prescott deviated from his original orders. Instead of occupying and fortifying Dorchester Heights and Bunker Hill, he took control of Breed’s Hill. Since it was closer to Boston, he reasoned that the rebel cannons stationed atop it would pose a greater threat to British shipping in Boston Harbor.

With the help of Chief Engineer Captain Richard Gridley, Prescott’s troops constructed a roofless, quadrangular fort on Breed’s Hill. Rather than refer to it as a fort, they called it a redoubt. Using pickaxes and shovels, the Patriots in the space of four hours constructed six-foot-high earthen walls that they reinforced with fascines, gabions, and empty barrels to absorb British shells. Inside the redoubt was a wooden platform the soldiers could stand on to fire over the walls. A single entrance was located in the rear of the redoubt.

The British reacted quickly to the Patriots’ bold gambit. Gage had planned to send an amphibious force to seize the position, but the Patriots had beaten him to it. Therefore, Gage decided to attack Charlestown Neck before the enemy strength increased around Breed’s Hill. Clinton proffered a plan by which he would take a brigade by boat up the Mystic River and land near Charlestown Neck. Such a move would seal off the peninsula, thereby trapping the entire rebel force. But Gage rejected Clinton’s plan on the grounds that the British lacked sufficient shallow-draft transport craft for such an operation. Furthermore, Graves refused to implement Clinton’s idea. He feared that his ships would run aground on the Mystic’s mudflats.

Howe suggested the plan that eventually was adopted. Howe would land a force at Morton’s Point where the danger of running aground was considerably less. The invasion force would then march around the northern flank of the enemy position and take the rebel redoubt from the rear. Howe was confident of success. Breed’s Hill was “open and of easy ascent and in short order would be easily carried,” wrote Howe. Howe’s plan was fraught with risk. He would be undertaking a direct assault on a fortified locale of unknown strength defended by an unknown number of the enemy.

Gage accepted Howe’s risky plan. Howe would lead the light, grenadier, and line companies of the 5th and 38th Regiments, which would debark from Boston’s Long Wharf. The remaining flank companies and the 43rd, 57th, and a portion of the 47th Regiments would embark from the Boston’s North Battery under the command of Brig. Gen. Robert Pigot. Howe would have overall command of the 2,200 British troops participating in the amphibious operation, and Pigot would serve as his second in command. Pigot’s troops would land on Morton’s Point in the early afternoon during high tide. Twenty-eight flat-bottomed barges would ferry the amphibious force. The two barges at the front of the flotilla would be armed with 3-pounder brass field guns to cover the landings. Clinton would command the reserve, which consisted of two battalions of Royal Marines. Once ashore, Clinton and Howe’s columns would chase the Patriots to Cambridge.

As Gage and his officers spent the morning debating how to get at the Americans ensconced on Breed’s Hill, the British warship Lively, on her captain’s initiative, shelled the American fortification. Graves, who was not yet convinced that war with the Americans was a certainty, ordered the Lively’s guns silenced.

Prescott attempted to use the unexpected ceasefire to erect a 150-foot-long earthen breastwork to cover the redoubt’s vulnerable left side. The Americans had barely begun the new construction when the British cannonade resumed in earnest. Gage had countermanded Graves’ order. British 24-pounders stationed on Copps Hill at the north end of Boston also joined in the bombardment. They were soon joined by all of the British warships in Boston Harbor, as well as those stationed in waters around the Charlestown Peninsula. In addition, the shallow-draft Symmetry was positioned to interdict Charlestown Neck. Fortunately for the Americans, the redoubt was strong enough to withstand the long-range bombardment.

The British plan was aggressive, bold, and ambitious, but it failed to take into account the capabilities of an entrenched enemy. While viewing the Patriot position on Breed’s Hill, Gage asked Loyalist Abijah Willard, who was standing with him, if he could identify the officer standing atop the redoubt. Willard said that it was his brother-in-law Prescott. “Will he fight?” asked Gage. “I can’t answer for his men, but Prescott will fight you to the gates of Hell,” replied Willard. Perhaps if a lesser man than Prescott had commanded the defenders on Breed’s Hill and no American reinforcements reached him between the time of the British council of war and high tide, Howe’s plan might have succeeded.

The American forces on Charlestown Peninsula vowed not to remain passive in the face of the British advance. Prescott desperately wanted to strike back. One of the guns in the redoubt began to shell the British atop Copps Hill. The Americans lacked powder, so the cannonading was largely for show.

With the redoubt completed, Prescott put Knowlton’s Connecticut regiment to work fortifying Bunker Hill to guard the American left flank. They deployed 200 yards back from the redoubt behind a tall fence with a stone base and rails for the upper section. Under Knowlton’s direction, the Connecticut men added additional rails to strengthen the barrier, referred to as the rail fence. Prescott, who deployed some of his force along a fence to his right in case the enemy tried to turn his flank, sent word to Ward that he needed reinforcements.

As Knowlton completed his rail fence, Prescott discovered his force was still vulnerable to attack on his left. He ordered his men to construct another earthen wall to the east. The wall would extend to an impassable swamp. This fortified line became known during the battle as the breastwork.

Unknown to Prescott, Ward had already detached men to come to his aid. Stark, with two regiments, had crossed Charlestown Neck earlier in the day. Viewing a gap of 300 yards on the rebel’s left between the breastwork and the rail fence as the weak point in their line, Stark joined Knowlton’s regiment at the rail fence and covered the gap in the line with three V-shaped defensive structures called fleches made of rails and dirt fronting some swampy ground. He also had his men make a stone barricade across the Mystic River beach to the water’s edge. Stark remained in this area. His decision to protect this sector proved critical to the strength of the Americans’ defensive position during the battle.

At 1 pmthe alarm was sounded in the American camp near Cambridge that the British were preparing a landing at Morton’s Point. Ward immediately directed 10 regiments to Bunker Hill. Two more were sent to Prospect Hill to protect the left flank, and another two were sent to defend Lechmere Point. In addition, Thomas’s men at Roxbury were put on alert.

Unfortunately, many of the American soldiers did not go where they were ordered. Some were caught in a bottleneck approaching Charlestown Neck, and others were delayed or turned back when they encountered the British bombardment of Boston Neck. Nevertheless, 1,000 Americans did reach Bunker Hill, and portions of five regiments went on to join Prescott.

The lack of any overall commander on the scene to direct operations was a serious flaw in the American defense. Problems arose controlling the large number of stragglers among the American army. Dr. Joseph Warren and Seth Pomeroy, both of whom were major generals of the Massachusetts militia, agreed to serve as volunteers; however, both declined to take command of the army.

With the leadership vacuum threatening to derail the American defense, Putnam assumed command and ordered troops to march immediately to Prescott’s aid. But the American troops milling about had received conflicting orders. Ward had told them to go to Bunker Hill, and now Putnam was telling them to do otherwise. Since Putnam had no authority over the Massachusetts troops, the rank and file ignored his entreaties. Still, he managed to persuade a small number of them into relocating the rail fence. What is more, some of them even went to join Prescott.

Captain John Callender’s Artillery Company had been forced to abandon its artillery pieces due to the intense bombardment of their battery by British warships and British guns deployed atop Copps Hill. Putnam ordered the small detachment of Connecticut troops to defend the rail fence. Most importantly, he rounded up volunteers to serve Callender’s guns. As the British attack loomed, Colonel Prescott would lead the 1,400 Americans that were positioned to receive the brunt of the assault.

As the Patriot army was arraying itself for battle, Howe landed on Morton’s Point at 2 pm. The presence of the Patriot army allowed him no opportunity to reconnoiter the ground. Howe therefore formed his men for the attack in three columns: Clark’s light infantry, Lt. Col. James Abercrombie’s grenadiers, and Brig. Gen. Robert Pigot’s foot soldiers. The light infantry advanced on the British right, the grenadiers in the center, and the foot soldiers on the left. Their preliminary objective was the rail fence. As for Pigot, his troops would demonstrate against the redoubt.

Sensing he was in for a hard fight, Howe called forward additional troops from Clinton’s reserves. When Howe’s artillerymen tried to drag their field guns to the top of Morton’s Hill, the heavy guns quickly became mired in the soft ground. When they eventually deployed their 10 cannons, his gunners discovered that they had the wrong size ammunition.

But that alone would not stop the attack. Howe gave the signal and the advance began. While the British light infantry was able to advance without difficulty, the lines of the tightly packed grenadiers soon became disordered. Undaunted by these unforeseen problems, the redcoats pressed on.

After pulling his men back to regroup following their initial assault, Howe led them forward in a second attack 15 minutes later. He directed Pigot’s men, reinforced by part of the reserve, to assail the redoubt. At the same time, Howe ordered the light troops and grenadiers to again attack the Patriots manning the rail fence.

This time they swung left and attacked the Patriots manning the fleches. The result was much the same, though. The Patriots poured a withering fire into the light troops and grenadiers. The British fell back leaving their path of attack strewn with dead and dying redcoats. In the space of just 10 minutes the grenadiers of the 4th King’s Own Regiment had suffered the loss of all but four of their men, the grenadiers of the 52nd Regiment lost all but eight men, and the 10th Regiment grenadiers all but nine men. Coming up to join the fight, the light troops of the 38th Regiment retired with just five enlisted survivors. Their commander had received a mortal wound.

With his men repulsed and every member of his staff either dead or wounded, Howe feared he was on the verge of a humiliating defeat. At that point, Pigot’s regulars and the Royal Marines began their advance against the Americans. They got close enough to trade fire with Prescott’s men, but they did not press their attack for they believed that Howe might be able to turn the American position by getting behind the Patriots. But when Pigot saw Howe’s column fall back, he realized that it was up to his troops to dislodge the Americans from their strong position. Pigot ordered the 38th and 43rd Regiments to assault the Americans from the east while the 47th regiment, the Royal Marines, and six light and grenadier companies attacked south.

The British closed within 60 yards of the redoubt before Prescott ordered his men to fire; however, they fired too soon and failed to inflict any damage on their target. Prescott ordered his men to hold their fire. The British interpreted the lack of Patriot fire as a sign the rebels were going to retreat. At that point, the redcoats charged. When they were within 20 yards of the American line, Prescott gave the order to fire. The British troops recoiled, falling back 150 yards. The British senior commanders observing the retrograde movement were shocked. Once again the British suffered staggering losses.

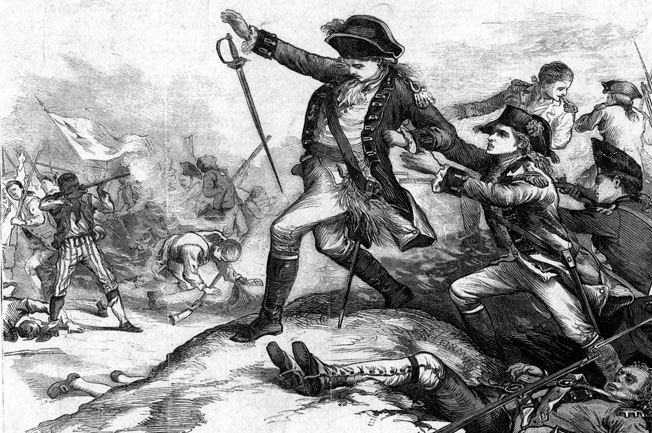

Burgoyne, who was out of favor with Gage and therefore had been relegated to being an observer of the battle from Copps Hill, had a radical take on the situation. He believed that the British might not have lost just the battle but perhaps the entire war. By that point, the Patriots on Breed’s Hill felt victory within their grasp. They cheered loudly as the British fled down the hill a second time. Despite their losses, the British were not done yet. As Howe reformed his men, Clinton crossed to the peninsula from Copps Hill and prepared to make another attack with the last of the British reserves.

Despite two failed assaults, Howe was determined to make one more attack. Howe carefully reformed his force into columns for a massed bayonet attack. The British soldiers were not to fire their weapons. No British musket fire during the assault by columns as they stormed the enemy lines.

The target of the third attack was not the rail fence. This time the objective was the redoubt and breastwork. Howe once again would lead the assault. He issued orders to the artillery to fire grapeshot. While some of the guns would pin Stark’s men in place and prevent them from firing on the attackers from behind, other guns would rake the breastworks with the intention of forcing Prescott’s men into the redoubt.

Inside the redoubt, Prescott began to doubt whether the Americans could win the battle. He had only 150 men remaining, and they were down to their last musket balls. Prescott could see Americans on Bunker Hill but did not understand why they uselessly remained there instead of coming to help him and his men. But he did not give up. “The best soldiers in the world cannot take the losses we have given them,” he told his men to instill confidence in them. The men cheered in response. “Lick them once more boys, and they’ll never come back,” Warren added.

Howe’s final attack was patterned much like his second one. A few men supported the artillery screening the rail fence, while the light troops of the 5th and 52nd Regiments and the remaining grenadiers feinted toward the fence. Following the feint, they wheeled south and struck the northern end of the redoubt. Pigot’s main force was to attack the eastern face of the redoubt, while Maj. Gen. Thomas Pitcairn again led the Marines and the 47th Regiment against the southern flank.

Prescott’s men held their fire until the enemy was within 20 yards, then unleashed their last rounds. Pitcairn fell mortally wounded, which slowed the British advance. But as the Patriots began to run out of ammunition, the redcoats climbed the rampart and thrust their long bayonets at the enemy. The Patriots, who were at a decisive disadvantage since they lacked bayonets, had no other choice than to swing their muskets as clubs and throw rocks at the attacking enemy. But clubbed muskets were simply no match for the bayonet thrusts of the determined redcoats.

At that point, Prescott ordered a general retreat. During the retrograde movement Warren was mortally wounded as he tried to form a rear guard. Prescott, as one of the last Americans to leave the redoubt, was nearly captured by the British, but miraculously avoided being bayoneted.

The Patriots fell back in good order toward Charlestown Neck. Stark’s men prevented Prescott’s group from being encircled. Putnam tried desperately to organize a stand on Bunker Hill but was unsuccessful.

Burgoyne, who was observing the Patriot army’s movements from Copps Hill, admired the resolve of the enemy. The withdrawal “was covered with bravery and military skill,” he said. Once they were back on the mainland, the Americans entrenched on Winter Hill to defend the approaches to Cambridge.

As the Americans escaped, Howe and Clinton met at the redoubt. Exhausted and demoralized, Howe had no interest in pursuing the enemy. Clinton did not argue the point; instead, he undertook to clear the peninsula of any remaining enemy forces.

The British won a tactical victory at Bunker Hill given that they controlled the battlefield at the conclusion of the action. But from a strategic standpoint, nothing had changed. The opposing armies held the same positions they had at the start of April. The British suffered a severe loss of manpower, while the Americans had depleted their stores of gunpowder. Because of their respective resource shortages, neither side would undertake any significant operations until the following year.

The British paid a high price for their victory. They suffered 226 killed and 900 wounded, which amounted to nearly half of their forces engaged. The loss of British officers in the battle was staggering. Of the British officers participating in the battle, 19 died and 70 were wounded. The officer losses constituted a quarter of the entire British officer casualties suffered over the course of the entire war. In contrast, the Americans had 140 killed, 271 wounded, and 30 captured. The bulk of the American losses were incurred during the retreat.

But the true import of the battle has to be seen through a political lens. Before the fight the dominant view in the American colonies was that they could reach an accommodation of some sort with Great Britain that would circumvent a costly war. That notion was shattered by Lexington and Concord and reinforced by Bunker Hill.

Even though the Americans fought from a fortified position, they had stood up to highly disciplined British regulars. Howe had underestimated his foe, and his decision to attack with the bayonet in the opening stages had cost the British army at Bunker Hill dearly. General Clinton made a trenchant observation when he stated that the battle “was a dear bought victory; another such would have ruined us.”

A superb review of the action at Breed’s Hill, with one note of correction: Pitcairn, the mortally wounded commander of the Royal Marines detachment, was a major, not a major general. Pitcairn Island in the South Pacific, of “Mutiny on the Bounty” fame, was named for him. Pitcairn was also well known to the Minutemen; he was the British officer identified as shouting, “Disperse, ye rebels! Lay down your arms and disperse” at Lexington shortly before the opening shots of the Revolutionary War were fired.