By Kevin M. Hymel

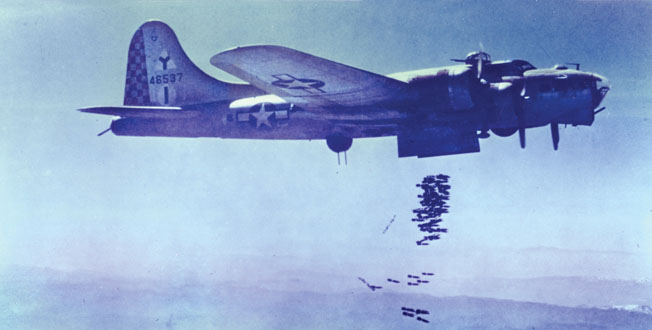

“Bombs away!”called out the bombardier of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber Great Speckled Bird, signaling the release of a full bombload over an enemy target. He was wrong. Two stubborn bombs refused to fall, remaining in their bomb bay racks.

The bomber’s radioman, Technical Sergeant Thomas Fitzpatrick, opened the bulkhead door to the bomb bay and saw the two remaining bombs. He reported it to the crew then took off his headphones and grabbed a screwdriver before entering the open bay as the bomber cruised at 250 miles per hour. Fitzpatrick wore no parachute, and no rope kept him from falling out. The only thing connecting him was the tube attached to his oxygen mask.

Walking gingerly along the eight-inch-wide catwalk down the center of the bomb bay, Fitzpatrick grasped onto handholds to keep his balance. “You could see the farmer with the pitchfork waiting for you,” he later mused. When he reached the bombs, he pushed the screwdriver into the holes in the upright bomb racks until the bombs dropped out. “It was a pretty hairy thing,” he said. With the bomb racks now empty, he worked his way back to his radio station and returned to duty. The task had only taken about a minute.

Fitzpatrick and his crew were part of the Fifteenth Air Force, 2nd Bombardment Group, 96th Bomb Squadron—the “Red Devils”—one of just six B-17 groups flying out of Italy, dropping bombs on German targets across southern Europe and dueling with the depleted Luftwaffe.

As the radioman, Fitzpatrick sat at a desk on the left side of the fuselage between the bomb bay and the ball turret and waist gunners. To his left was a small window and above him large one. He sat facing forward, using the shoeboxsized radio on his work desk to send after-action reports in Morse code or receive new targets if the primary target had changed. He was also the bomber’s designated first aid man. His other duties included visually confirming a successful bomb drop and, of course, prying unreleased bombs from the bomb bay.

Fitzpatrick hailed from Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania, where he lived with his parents and older sister. He grew up in a Catholic household and enjoyed cane-pole fishing with his father in Wissahickon Creek and playing the bugle for his Boy Scout troop and the American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps. He learned about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor over the radio at the local drugstore, where he served sodas to customers. As a 17-year-old senior at Philadelphia’s Northeast Catholic High School, his first thought was, “I don’t know if I’m old enough [to serve].”

Once he finished school, Fitzpatrick landed a job as a lab assistant at a local U.S Department of Agriculture lab, where he worked on projects like acrylic rubber, a bulletproof material that would not disintegrate in oil or gasoline. When the Army Air Forces began accepting non-college graduates, he took the aviation cadet examination. After scoring a 99, he went to Keesler Army Airfield in Mississippi for infantry training. He was soon detached to Moorhead State Teachers College in Minnesota to learn to fly Piper J-3 Cub training planes. “It was a breathtaking experience,” he said.

Aside from flying, Fitzpatrick worked another job, one that focused on the field’s strict military training: he became the base bugler. “Every morning I played Reveille and [To the] Colors.” He played bugle for the next three months, often playing Taps at military funerals.

Next, Fitzpatrick went to Santa Ana Army Airbase, California, for his classification. He did not make pilot or bombardier, so he selected radio operator, an enlisted rank. He then traveled to Scott Field, in Illinois, for radio training. He learned to use the radio’s knob to find the correct frequency by listening through his headphones for a whistle that went down and then up again. “You wanted the null between the high and the low pitches,” he explained. Once he had the frequency, he could switch his radio from intercom to inner squadron and back to wing headquarters. Fitzpatrick could tap out 25 words a minute in Morse code, but he would never use the inner squadron option. “The pilot just used his voice,” he said.

Fitzpatrick also controlled the antenna wire, which he reeled out beneath the bomber to a length of about 100 feet. A weight at the end of the copper wire kept it steady. “When zeroing in the radio,” he explained, “I would reel out the wire until I got that oral null.”

The radio contained a small magnesium bomb inside. If his plane were going down, Fitzpatrick had to press a special button on the radio, and it would begin to burn. He would then put all his radio codes into the open back of the radio to ensure their destruction.

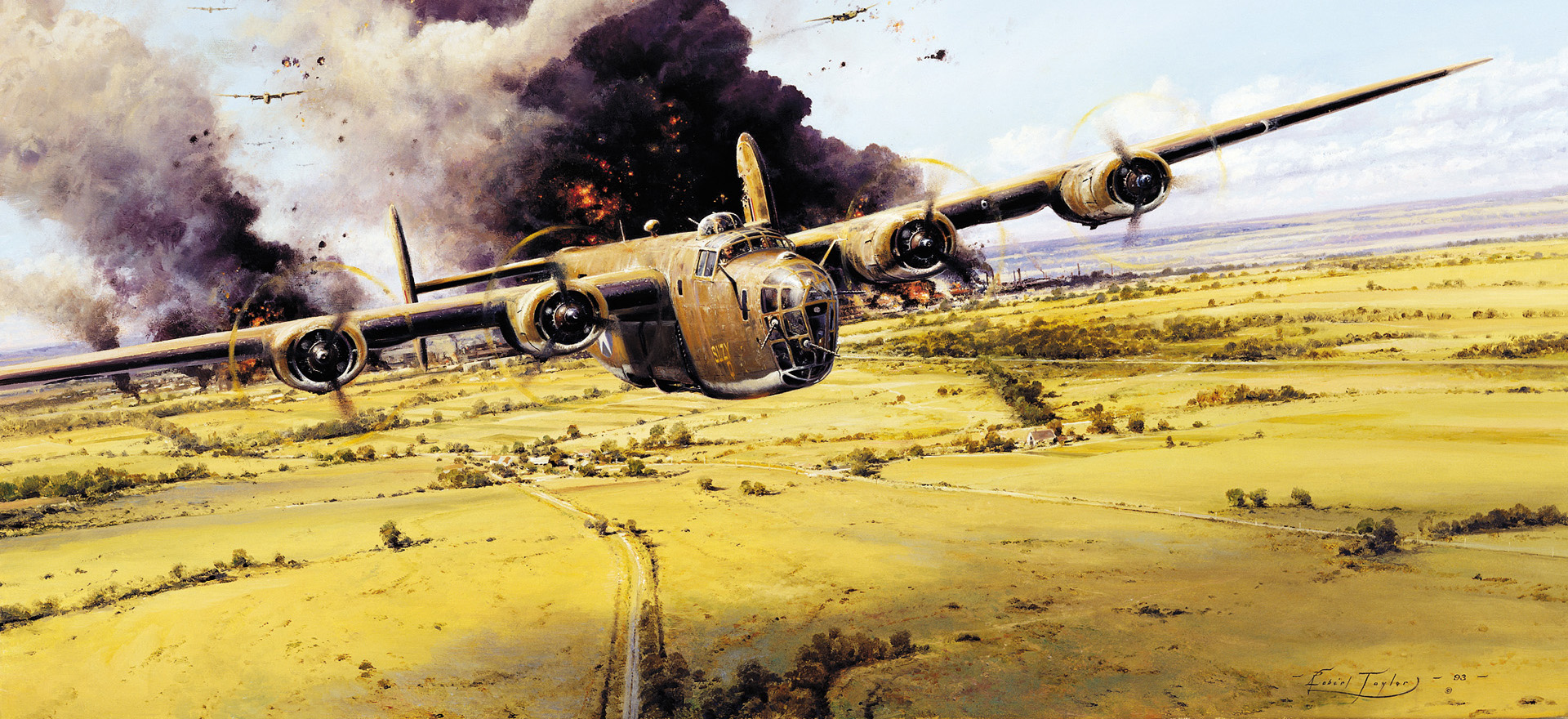

Next, Fitzpatrick headed to Yuma, Arizona, for gunnery school and B-17 training. The four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress strategic bomber carried a 10-man crew. While it could not match the wider Consolidated B-24 Liberator’s bomb load, it gained a reputation as a rugged bomber that could absorb heavy enemy fire and bring its crew home. The B-17 carried a maximum bomb load of 8,000 pounds in four racks behind the flight deck. Thirteen .50-caliber machine guns defended the bomber from nose to tail, hence the name “Flying Fortress.”

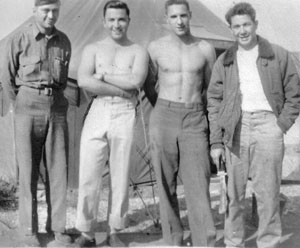

Now fully trained, Fitzpatrick went to Plant Park in Tampa, Florida, on August 10, 1944, to join a crew. His bomber crew consisted of himself, pilot Lieutenant Clifford Foos, copilot Lieutenant Robert Clarke, navigator Lieutenant Malcom Sharpe, upper turret/flight engineer Sergeant Grover Themer, ball turret gunner Corporal Joe Martin, waist gunners Corporal Bill Kontra and Corporal Bernard Sepolio, and tail gunner Corporal William Emslie. They had not yet been assigned a bombardier. “We had a great pilot who won a lot of decorations,” Fitzpatrick said of Foos, “and a pretty damn good crew.”

He was not bragging. When his team made Crew of the Week at McDill Air Force Base, Florida, they were rewarded with flying the famous Memphis Belle, the first B-17 to survive 25 missions with her crew intact, to New York City for a War Bond drive. “The plane was fairly rickety,” recalled Fitzpatrick. Unfortunately, as the bomber approached New York clouds rolled in over the city. Foos, who had not yet been trained on instruments, had to land in New Jersey, where the men spent a few days before returning to Florida.

The crew took off on November 6, 1944, for Bangor, Maine, the first leg of their journey to war. They flew in a special “Mickey” B-17, which contained a retractable H2X radar device under the nose to help bomb through heavy clouds and jam German radar. They brought a Mickey operator with them. From there, they flew to Gander Airport in Newfoundland, Canada, for the flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately, eight feet of snow fell on November 22, Thanksgiving Eve. All flights were grounded. As plows cleared the tarmac, the American airmen paraded for Thanksgiving Day. “Locals had never heard of Thanksgiving,” said Fitzpatrick. “They thought it was great.”

While they waited, mechanics installed rubber fuel tanks in the bomb bay to help complete the ocean flight. Fitzpatrick recognized them as acrylic tanks, the same material he had worked on as a civilian. “Here I am a year later and we had bulletproof gas tanks,” he recalled. Eventually, the squadron took off for the Azores, more than 850 miles west of Portugal, but Fitzpatrick’s bomber stayed behind with mechanical trouble. With reports of German raiding parties being landed by U-boats to plant bombs in the bombers, Fitzpatrick and his crew took turns sitting in the cold plane and clutching Tommy guns.

Finally, on December 2, the weather cleared and a strong tailwind blew in. With the navigator, Malcom Sharpe, hung over from a night of drinking, the men threw him into a shower, fed him coffee, and loaded him into the bomber. They took off. Fitzpatrick contacted the Azores, and the plane flew on across the ocean. Fitzpatrick had to act as both radioman and navigator while Sharpe recovered. The trip proved uneventful. “It’s awfully lonely over the Atlantic all by yourself,” Fitzpatrick admitted.

Fitzpatrick used his radio compass to navigate the bomber, contacting the Azores and a station in Iceland and giving them his latitude and longitude so they could give him a heading, which he gave to Foos. As they approached the Azores, Sharpe recovered and resumed his navigation duties. “I guess he wanted to put something into his log book,’ said Fitzpatrick. The bomber headed for Lajes Field, a clifftop base on the edge of Terceira Island. The bomber’s altitude went from a couple hundred feet to almost zero in seconds. Not realizing this, Fitzpatrick failed to reel in his antennae, which tore off as the plane touched down. “I got a few words from the major who met us,” Fitzpatrick recalled.

Portugal had leased Terceira to Great Britain, giving the pilots a safe haven in the Atlantic. Fitzpatrick was getting closer to the war. He saw battered ships pulling into the harbor with holes in their sides. Across the straits, on the island of Sao Jorge, he could see Swastika flags flapping in the wind. The crew was told to stay put lest they encounter bubonic plague-infected rats. “They had a rat patrol,” said Fitzpatrick, “and a big pit where they burned the rats every morning.”

From the Azores, the men flew to Marrakesh in French Morocco. As they taxied down the runway, a regiment of French Foreign Legionnaires (FFL) presented arms on the tarmac while a band played “La Marseillaise.” The Frenchmen cheered their American friends with “Vivé le morté! Vivé l’guerré! Vivé l’legion Etrangere!” (Hurray for death! Hurray for war! Hurray for the Foreign Legion!) That night Fitzpatrick dined on horse and camel meat.

From Marrakesh, the crew flew across North Africa to Tunis and then to southern Italy, eventually making it to Amendola Airfield between Foggia and Manfredonia on Italy’s Adriatic coast on December 9. There they joined the Fifteenth Air Force, 2nd Bombardment Group, 96th Bomb Squadron. The Fifteenth consisted of 15 B-24 Liberator groups of 72 bombers each and six B-17 groups of 96 bombers each. Anywhere from 700 to 1,000 bombers could get aloft for missions over enemy targets.

Although Italy had turned against its Nazi partner more than a year earlier, Fitzpatrick noticed that fliers still wore their sidearms. Earlier in the Italian campaign, American bombers flying out of North Africa had hit the area. Prior to the raid, they had dropped leaflets warning the civilians to take cover. Unaware of the Americans’ target, local civilians packed into the railroad yard’s underground bomb shelter, not realizing they were in the raid’s bull’s-eye. Bombs hit the yard, destroying gasoline-filled tank cars. The fuel flowed into the shelter and exploded, killing almost everyone inside. Despite the warning, the locals blamed the Americans for the heavy toll. “It was a little on the hairy side,” said Fitzpatrick of the area and its citizens.

By the time Fitzpatrick’s crew arrived at their new home in December 1944, the war had shifted decidedly in the Allies’ favor. The Western Allies had liberated most of France and entered Germany, although Adolf Hitler was about to launch his Ardennes Offensive—the Battle of the Bulge. The Soviets had driven the Germans out of their country, as well as Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Albania. The advancing Soviets had also taken huge swaths of Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. Back in August, King Michael of Romania had staged a coup against the pro-German government and surrendered to the Russians. The oil refineries of Ploesti, which had been the target of so many Allied bombing attacks, were now in Allied hands.

In Italy, Rome had fallen to the Western Allies on June 4, 1944, during an advance some 300 miles up the Italian boot. Despite the diversion of men and materials to the invasion of southern France and operations in Greece, the Allies had penetrated the German Gothic Line. There was, unfortunately, no decisive breakthrough, so they fought an offensive defense to keep the Germans from fortifying other fronts. When Fitzpatrick and his crew touched down in Italy, the Allies were still 100 miles south of the Po River, the last natural barrier into central Europe.

After deplaning, Fitzpatrick’s crew had no tent to sleep in, but when a bomber blew up on the runway, killing its crew, Fitzpatrick and his men occupied the dead crew’s tent. “That’s when we realized that we were at war,” he said. Fitzpatrick’s crew received a war-weary B-17F, the Great Speckled Bird,so named for the bomber’s numerous patched flak holes from previous missions.

Before his first sortie, Fitzpatrick got a little absolution, and a laugh. On Christmas Eve, despite a heavy downpour, he and 3,000 other airmen packed the San Lorenzo Maiorano Cathedral in Manfredonia. Airmen gave generously during the collection, creating a huge five-foot-tall pile of money in front of the altar. Then a pyrotechnic wire-guided dove model swooped down the center isle and exploded over the pile, setting the money on fire. Three airmen quickly doused the fire with their wet coats. The men in the pews cheered.

For their first mission, just before Christmas 1944, Fitzpatrick’s crew bombed the small town of Castlefranco Veneto, northwest of Venice. Only a small amount of enemy fire—all flak from antiaircraft guns—greeted them. “It was a milk run,” he explained.

Despite the milk run aspect of the mission, Fitzpatrick learned to do his job in combat. “Once we got into enemy territory we kept radio silence,” he said. The Alps, separating Italy from central Europe, stood as the marker for going quiet. After the bombs dropped, he sent his crew’s bomb report in Morse Code.

So began Fitzpatrick’s life as an air warrior. At first, bomber crews had to fly 25 missions to earn the right to rotate home. Because of high casualties, the Army Air Forces leadership increased the number to 30. The crews rotated, and as a result Fitzpatrick flew every third day. “I got 25 missions in before the end of the war,” he said. “I did most of my flying in the winter of ‘45 and the spring.”

Almost every morning, Fitzpatrick and all the other airmen awoke early and ate breakfast at 4 am, then headed over to their morning briefing. It was usually their last meal before a mission since food froze at 10,000 feet. “We could only then eat crackers,” he recalled about the K-rations they brought onboard, but the men did not mind. The missions were too tense for meals. “I never remember feeling hungry.”

The crew wore Class A uniforms, including neckties. “The Germans were conscious of rank,” explained Fitzpatrick. “We had to impress them if we were captured.” Over their uniforms they wore insulated, electrically heated suits that plugged into sockets in their seats. Heated gloves and boots snapped into plugs on the suits. Early on, the crews wore British heated boots, which were so cold they turned up the heat in their suits to the point of burning just to warm them. Finally, they were issued American-made heated boots inside their fur-lined covers. For extra protection, Fitzpatrick wore a Saint Christopher Medal—Christopher being the patron saint of travelers —and a Miraculous Medal, which would help believers obtain grace with the help of the Virgin Mary.

Before every mission the men received survival kits containing a compass, maps, $1,000 in gold notes, and other important items, which they wore in a pocket below one of their knees. The kits were strictly accounted for, and each crewman had to return his after every mission. Crews also received the names of German prison guards who could be bribed, information brought back from those who successfully escaped German prison camps.

Staff officers briefed the pilots and radiomen separately before every mission. Fitzpatrick and the other radiomen received daily codes and weather reports. The pilots, navigators, and bombardiers received targets and secondary targets. Surprisingly, the only other person who knew the wing’s destination was Axis Sally, the American-born woman employed by the Nazis to lower GI morale. Her programs mixed popular American music with propaganda and threats. “You’re coming up to Wiener Neustadt [Austria] and we’re ready for you,” Fitzpatrick remembered hearing her say over the radio. Every briefing ended with the men synchronizing their watches to keep accurate time and to ensure all elements of the mission were coordinated.

Once fully briefed, the crews were trucked out to their bombers, where they greeted the ground crews who were tasked with loading the planes with ordnance and fuel, as well as caring for their bomber and crew. “They mothered us,” Fitzpatrick said of his ground crew, who constantly patched flak holes and worked on the Great Speckled Bird’s faulty turbo supercharger. “They were the unsung heroes of the war.”

Like many planes late in the war, Great Speckled Bird was unpainted and showed its silver aluminum body. Camouflage had proved ineffective for disguising the planes on the ground, especially since the Luftwaffe rarely flew over the air base. The parasitic drag of camouflage paint also slowed the bombers. “You could get additional speed without it,” explained Fitzpatrick.

Next to every bomber stood an outhouse, which the men used before climbing into their craft. There were no bathrooms on a B-17, only a tube for urinating, particularly difficult for men wearing insulated clothing. Eventually, Great Speckled Bird’s crew learned to drink only one cup of coffee at breakfast. “That way,” recalled Fitzpatrick, “your kidneys did not have to work overtime.”

Before takeoff, Fitzpatrick would turn on his IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) signal. Earlier in the war, the Germans had repaired downed B-17s and bombed England with them. To fight the tactic the Allies developed the IFF signal. If bombers approached Allied territory without it, they would be shot down. Unable to hear the signal, Fitzpatrick would ask the tower, “How does my cockerel crow?” an inquiry as to whether his IFF switch was on or off, and the tower operator would reply, “Your cockerel crow is loud and clear.”

As the bombers lined up and headed down the runway, the squadron chaplain would stand in the back of his jeep and give absolution to the crews as their planes lumbered into the sky. Fitzpatrick liked his chaplain, but it bothered him that there were never services for lost crews.

Once the planes formed up and headed to their target, Fitzpatrick would sometimes receive messages from wing headquarters to change targets, usually because of clouds or because a target of opportunity suddenly became available. He provided the new information to the pilots and navigator, who would make the necessary course corrections. The missions usually lasted about 10 hours, yet there was almost no down time on a flight. “We were constantly on the lookout for enemy planes,” he explained.

When the bomber reached 10,000 feet, the men put on their oxygen masks. B-17s usually flew at 25,000 feet or higher, where antiaircraft gunners had a hard time targeting them. A few times they bombed from 18,000 feet, like the raid on Munich, Germany, where the bombers hit marshalling yards and rolling stock. “The antiaircraft could find you quicker,” said Fitzpatrick. “That was pretty scary.” Another low-level attack targeted an enemy airstrip. “You could see planes on landing strips at that altitude.”

The targets themselves could prove surprising. On one run over a small town at 18,000 feet, the group dropped bombs on some storage buildings. “There were huge explosions,” said Fitzpatrick. “Green and yellow clouds of smoke came from whatever they were making in the factory.” Usually, exploding buildings created white clouds, while oil refineries produced black. The men had hit a hidden chemical complex.

By this point in the war, bombers were escorted by fighter planes all the way to their targets and back. Drop tanks under the fighter planes’ wings increased their range. On the way back from one mission, Great Speckled Bird’s temperamental turbo supercharger failed, and the B-17 fell behind the group. They were flying alone over enemy territory when Fitzpatrick looked out his window and saw two North American P-51 Mustang fighter planes escorting the bomber. He immediately felt relieved. “I don’t know where they came from,” he said, “but I was very, very, very happy.”

The planes’ tails were painted red. Fitzpatrick knew that meant they were Tuskegee Airmen, the African American fighter unit, men who had to fight just to get into the war in a segregated military. “We knew they were based not far from us,” he said. “We would see them make barrel roles over the airstrip if they made a kill.” The two fighter pilots protected the Great Speckled Bird all the way back to Amendola.

Whenever a bomber was hit, Fitzpatrick and his crew counted the parachutes coming out of the stricken plane. “That happened all the time,” he said. They would report the stricken bomber’s number during their debriefings. On one mission, Fitzpatrick heard a faint radio transmission as a B-17 went down over Yugoslavia. “Going down over Yugo,” the radioman on the falling B-17 repeated in the clear, adding his longitude and latitude. Fitzpatrick radioed the information back to wing headquarters so they could steer partisans on the ground to the crash location before German soldiers reached the crew. “I was the only one who picked it up,” he said. “I never knew what happened to the crew.”

Whenever downed airmen made it back from enemy territory, the crews were debriefed. One group showed up in civilian clothes provided to them by partisans. While traveling out of the occupied area in a train, one of the crewmen rested his feet, still clad in American boots, on a small heating stove. A passing civilian told him that the letters “US” were branded on the bottom of his boots. The civilian did not report the American, but the word went out to the Fifteenth Air Force to correct it. “Everyone had to get a red-hot poker and eradicate the ‘US’ on the bottom of their boots,” said Fitzpatrick.

With Russian-occupied Hungary now on the Allied side, the town of Sopron provided the Americans an emergency airstrip. Fitzpatrick’s crew landed there once when they ran low on fuel. They found the airbase run by women and 12-year-old boys. “Kids jumped on the wing and refueled,” he said. “These old ladies would pick up two [50-pound] packs with parachutes and flight suits in them.” That night, the crew dined on cabbage and potatoes.

German planes and flak frequently hit the bombers. German Messerschmitt Me-109s would fight through the fighter escorts to shoot down B-17s. As the end of the war neared, Fitzpatrick and his crew started seeing a strange new fighter plane with a bat-shaped wing and no propeller. It was the Messerschmitt Me-262, the first operational jet of the war. “We didn’t know what the hell they were,” said Fitzpatrick. “I could see them traveling much faster than usual planes.” On a mission over Munich, rocket-firing 262s had to fly a large circle to get into a firing position behind the bombers. Emsley, the tail gunner, realized their tactic and shot one down.

While enemy planes did not show themselves on every mission, antiaircraft fire did, and there was no defense against it. “Flak was getting more intense all the time,” said Fitzpatrick. “You could get out and walk on it.” Once while sitting at his desk an antiaircraft shell exploded outside his window and a piece of flak tore through the fuselage just behind the window. Fitzpatrick instinctively jerked his head back. Just then, a second piece blasted through the hole made by the first and shot through the bomber, tearing out the other side. “That was a narrow escape,” he recalled. Although flak never wounded Fitzpatrick, the plane would sometimes touch down at Amendola with as many as 60 holes in it.

Fitzpatrick’s ball turret gunner was not so lucky. “I’m hit!” Joe Martin called out just after dropping bombs over Austria. Fitzpatrick unhooked his oxygen tube and dashed back to the ball turret. He had just opened its lid and pulled Martin up when he passed out from lack of oxygen. One of the crewmen hooked up Fitzpatrick with a walkaround oxygen bottle, and he came to. They then pulled Martin into the radio room, where a recovered Fitzpatrick tried to help.

They laid Martin on his belly, exposing a large wound in his buttocks. Although the ball turret seat was armored, Fitzpatrick knew Martin always sat high in the turret, exposing his bottom. First, Fitzpatrick cut Martin’s heated suit to access the wound, cutting off his heating circuit in the process. The men rotated their gloves and boots to Martin to help keep him warm. Once the plane passed over the Alps, Foos dropped the plane down to a warmer altitude, and Fitzpatrick went to work. He found a piece of flak the size of a fist imbedded into Martin’s left buttock and pulled it out. He then sprinkled sulfa powder into the wound. If Martin had been in pain, Fitzpatrick would have given him a morphine shot, but the gunner remained calm.

When the bomber arrived over the airfield, the flight engineer, Grover Themer, fired a red flare into the sky indicating that they had a wounded man aboard. Wing headquarters rerouted the bomber to an airstrip next to the 61st Station Hospital at Foggia. As the bomber taxied down the runway, an ambulance raced alongside. When it came to a stop, the crew helped load Martin into the ambulance for the trip to the hospital where doctors picked several personal items that he had kept in his back pocket out of his wound.

When the crew returned to their airstrip, one of the ground crewmen pried a piece of flak out of the ball turret and gave it to Fitzpatrick to give to Martin. “He didn’t fly anymore,” said Fitzpatrick. It had been Martin’s 12th mission. The crew received a new ball turret gunner.

The flak did not let up. On another mission over Austria, it hit the Number One engine. Flak cut the propeller’s drive shaft, and Foos attempted to feather it, turning the blades into the wind to reduce wind resistance. But the blades did not respond and began wind-milling at high speed, shaking the plane, as Fitzpatrick remembered it, “like a milkshake.”

Then the engine caught fire. Copilot Robert Clarke pulled the lever on a CO2 fire bottle in the wing to extinguish the flame. Fitzpatrick could still see flames and told Clarke it had failed, so Foos rang the bail out bell. Everyone put on their parachutes, knowing if Foos rang it again they would have to jump. Clarke pulled the lever on the second CO2 fire bottle. This time the flame went out. As the bomber flew over the Alps, another engine failed and had to be feathered. Foos managed to get the plane up to 18,000 feet to cross the Brenner Pass, then landed back at base. They inspected the damage to find the fire had burned through a spar between two gas tanks. Amazingly, the tanks never caught fire. Foos received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions.

There were other dangers. Coming back over the Alps after a bomb run, the bomber hit a downdraft and dropped 5,000 feet in just a few seconds. Fitzpatrick, who never wore his seatbelt at his desk, split his head on the ceiling. Blood oozed out of the wound. With great effort, Foos and Clarke leveled the plane and brought the crew home.

Once on the ground, the flight surgeon cleaned and bandaged Fitzpatrick’s wound. He then told Fitzpatrick he could thumb a ride to the hospital at Foggia where they would award him a Purple Heart, or he could go to dinner. Fitzpatrick weighed his options. He had been wounded on a nine-hour mission over enemy territory with a troubled engine that threatened to kill the entire crew. He opted for dinner. The doctor poured him a double shot of good Army whiskey and sent him on his way. “I appreciated that double shot,” he said.

With his head wrapped in bandages, Fitzpatrick sat down in the mess hall for dinner. Two new crews who had just arrived from the United States looked at him aghast. “They were probably thinking, ‘What were we getting ourselves into?’” mused Fitzpatrick.

While on the ground, Fitzpatrick witnessed a different kind of horror. The day after injuring his head he watched as one of those two new crews flew a practice mission in the rain and slammed their bomber into a hillside. “Troops had to go up there and get the bodies,” he recalled. In another incident, he watched a B-24 Liberator’s engine explode and the bomber go down. He did see parachutes pop out of the falling plane. “There must have been some kind of malfunction,” he said, “and they knew to abandon the plane before it blew up.”

British troops, who shared the base with the Americans, brought a different tone to the war. Bagpipers played every morning. One Highlander would sneak Fitzpatrick a rum ration in a silver cup and occasionally invite him to the British mess, where he enjoyed dishes like fish and chips and kidney pie. “We ate pretty good.”

The British helped defend the air base from Bed Check Charlie. “A German came over every night and tried to bomb us,” said Fitzpatrick. A British searchlight would pierce the night, followed by antiaircraft fire. “Sometimes they got him,” said Fitzpatrick. “Sometime they didn’t.” When the alarm went off, Fitzpatrick and his crew jumped out of their tents and dove into trenches, sometimes filled with freezing water. “After a while, we just forgot that,” he said.

Surprisingly, the Americans got along well with captured German airmen, whom they called their little brothers. “The common denominator was we were all fliers. If you got shot down they would take better care of you than the SS,” said Fitzpatrick. “We treated them the same way.” The POWs enjoyed the same food as the Americans and were allowed to watch the same movies. The Americans sometimes chatted through the wire with those Germans who could speak a little English, but for the most part the POWs kept to themselves and played soccer.

One person the American bomber crews did not get along with was their new commanding officer (CO). A West Point graduate who was big on ceremony, he ordered everyone to fall out in their dress uniforms for Reveille. “We hadn’t had that for a year,” said Fitzpatrick. Although the men wore dress uniforms on missions, they usually wore t-shirts and shorts—and some wore kilts—on the base as the weather warmed. For the new CO’s first Reveille only the new crews showed up. Furious, the CO ordered everyone to fall out for the next morning’s Reveille. “We got to those new crews and told them to stay in bed.” No one went out the next day. Again, the CO was furious, but he got the message and gave up on the ceremony.

During down time the men stayed at a beach house in Manfredonia, where they could take a sailboat out into the Adriatic Sea or just relax on the beach. “We would go swimming, and girls would come down there completely stripped and put on their bathing suits,” said Fitzpatrick. Unfortunately, he never had the opportunity to go fishing.

When Fitzpatrick finally earned some rest and relaxation time, he went on a Red Cross-sponsored trip to Rome. He slept at a mausoleum and toured Vatican City with an American-educated guide named Francesco Federici. They toured the Vatican Library, the Sistine Chapel, and met Pope Pius XII. A group of about 12 Americans were brought to an upstairs room in the Vatican where they waited for the pope. When His Holiness entered the room, the men cheered “Viva El Papa!” The pope then looked at each man’s rank and insignia and spoke to them in English. He then gave a prayer for each man’s family, followed by a papal blessing.

As the war wound down, the bombers went on a mission that irritated Fitzpatrick. On March 25, with only six weeks left in the war, the bombers raided a tank factory in Berlin that had already been leveled by the Eighth Air Force flying out of England. Two bombers and their crews were lost at a time when German civilians often killed downed airmen. “They just wanted to get it into the books that we bombed Berlin with 145 bombers,” he explained. Fortunately for Fitzpatrick, he had rotated out of that mission. “Sometimes the flip of a coin can make a difference,” he noted.

In the last month of the war, the bombers attacked a series of roads and bridges over which the Germans were fleeing while the British Fifth Army pursued. One of the 1,000-bomber missions committed a tragic mistake. On every mission the lead bombardier, using the Norden bombsight, would drop his bombs and the other bombardiers followed. The lead bombardier would click his Norden sight forward 45 degrees to lock onto the target, then click it back to the ground below so the plane would drop bombs automatically on target. On this particular mission, the leader clicked his sight up but forgot to click it back. “So instead of bombing at a 45-degree angle,” said Fitzpatrick, “we dropped on Brits south of the Po River.”

The next day the bombers went up on the same mission. This time the British fired their antiaircraft weapons straight up in the air, on either side of the approaching air fleet, creating a clear corridor. There were also large orange arrows on the ground pointing to the Germans. “They must have had casualties [the day before],” explained Fitzpatrick. “That pained me greatly.”

On April 25, 1945, the 2nd Bomb Group hit Linz, Austria, followed on May 1 with a mission to Salzburg. On May 6, the Fifteenth Air Force ran out of enemy targets. Three days later, Germany surrendered, and the war in Europe ended. “We went wild and drank wine,” said Fitzpatrick. The ground crews took flares out of the planes, planted them on a hill, and set them off. “We lit 1,000 red flares to celebrate,” he said, “and they burned for a long time.” The Americans opened the POW camp gates, but the Germans refused to leave. They knew their world outside had been destroyed and simply finding food would be difficult. As the days passed, the restless Americans began drinking and getting into fights. Soon their superiors confiscated their firearms.

Fitzpatrick and his crew took on a new mission, flying high-ranking officers around Europe. On a trip to Pisa, Italy, he and his flight engineer took a break at a bar. When Fitzpatrick entered, he spotted a friend from Pennsylvania. “Hiya Tom” the friend called out. “Hiya Jim,” Fitzpatrick shot back. It was as if they had not seen each other for just a few days. On a trip to Vienna, Austria, Fitzpatrick went to a hotel where he paid the bar’s piano player a dollar to play “Vienna, the City of My Dreams.” The man played the song. He then played it again, and again, and again. Fitzpatrick eventually had to pay him another dollar just to stop.

With the war in Europe over but combat still raging in the Pacific, Fitzpatrick and his fellow fliers flew British Gurka and Sikh troops out of Italy on the first leg of their trip back home. “They did everything with a big smile,” recalled Fitzpatrick. One Sikh boarded his B-17 holding a bugle. “Hey sport,” Fitzpatrick said to him, “how about you give me that bugle.” The soldier replied “No sahib, its mine.” Fitzpatrick was undeterred. “Yes, but it’s my airplane.” The soldier coughed it up. “He swapped it for a plane ride to Naples.”

When Japan surrendered on August 14, Fitzpatrick earned the right to go home. “We were happy when they dropped the bomb,” he recalled about the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. American fliers had the option of taking a plane or ship home. When Fitzpatrick heard about a plane crash soon after takeoff, he decided to go by ship. He boarded the Victory ship SS Lake Charles Victory where, as one of the highest ranking noncommissioned officers, he was responsible for feeding 500 infantrymen three times a day. He spoiled the returning veterans, giving them extra milk and anything else he could find. He treated them better than himself. “I lost about 20 pounds coming back on that ship,” he said.

After 14 days at sea, the Lake Charles Victory pulled into port at Newport News, Virginia. After mustering out of the service, Fitzpatrick and some other veterans rented a car and drove to Washington, D.C. Fitzpatrick then took a train to Philadelphia and a local train home. As he walked up his street, his sister and cousin ran to him and hugged him. When he got home his mother inspected him head to toe. “I passed muster,” he said.

Since it was too late in the year to go back to school, Fitzpatrick temporarily returned to his job at the USDA lab, receiving his replacement’s promotions. He eventually earned a degree in chemistry from Penn State University in 1950 and went on to earn a master’s degree from the University of Maryland and a Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts in 1963. He spent the rest of his career at the USDA laboratory. He bought a house in Flourtown, north of Philadelphia, and decorated his den with the bugle from India (where it hangs today). To him, it represents the end of the British Empire. He moved his parents in to take care of them. “They needed me,” said Fitzpatrick. He got engaged once but never married. “I still have girlfriends,” he muses today.

In 1990, Fitzpatrick watched the movie Memphis Belle, starring Matthew Modine. While he enjoyed it, he did not like the scene were a panicked crewman refused to go on a second bomb run. “We would have shot him,” he said. “Sometimes we had to go around the third time, and by then the enemy had our range.” But he liked the movie enough to see it twice, and said the portrayal of the radioman was accurate “even though there wasn’t much of it.”

As a biochemist, Fitzpatrick helped invent prenatal vitamins and many other things in use today. After fighting for his country and working at the USDA lab for a combined 40 years of service, he retired at age 55. “Since then,” he said, “I’ve caught a lot of fish.” At age 92 in 2017, he continued to ride horses and hunt big game.

Fitzpatrick is proud of his service and the might of America’s military strength. One day, when his crew led a 1,000-bomber mission, he looked out his side window and counted at least 100 planes. The sight inspired him. “That was the U.S.A.,” he recalled. “That was Uncle Sam.” He looks back on the experience with an appreciation of America’s modern air force. “Of course,” he said, “two bombers could do the same job today.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Air Force Chaplain Corps and author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It. He is also a tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours and leads a tour of General George S. Patton’s battlefields.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments