By Patrick J. Chaisson

Ensign Doran S. Weinstein, a U.S. Navy communications officer, stationed himself outside the bridge of a troop transport named SS President Coolidge as it approached the South Pacific island of Espiritu Santo on Monday morning, October 26, 1942. The sight of Espiritu Santo’s green palm trees meant Weinstein’s vessel was finally nearing the end of its 6,800-mile voyage from San Francisco.

Weinstein, however, had no time to look at trees. His job was to keep alert for friendly signal lamps, as well as for the telltale signs of an enemy submarine periscope. Around 0930 hours, he observed through his binoculars a shore-based light attempting to contact him with an urgent message.

It read: S-T-O-P.

Weinstein dashed inside to warn the ship’s captain, who immediately ordered his engines to full reverse. Meanwhile, an assistant signalman decoded the rest of the warning message. “You are standing into mines,” it said. Other watch standers reported seeing several of those deadly spheres close aboard—added proof the President Coolidge was indeed sailing through an American minefield.

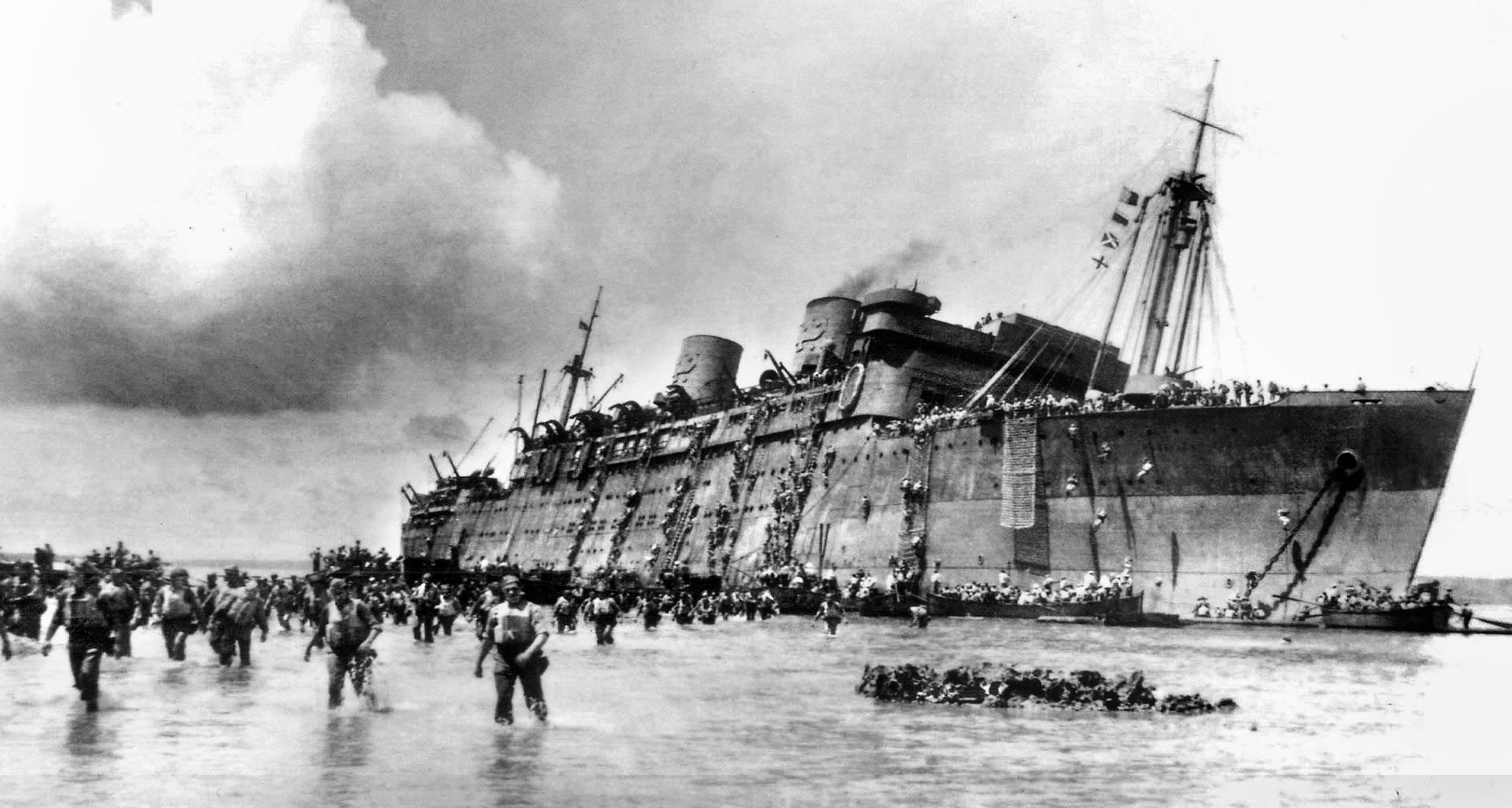

At 0935 hours, tragedy struck when the first of two sea mines detonated under Coolidge’s hull. She rolled over and sank 78 minutes later, although miraculously, only two of the 5,440 men on board were killed that fateful morning.

Weeks later, a naval court of inquiry convened to investigate the facts behind this maritime disaster. Its members also sought to identify and punish whoever was responsible for allowing the President Coolidge to proceed into a channel blocked by friendly mines.

“Someone had blundered,” the commission’s report concluded. But who? Could the ship’s captain, a 63-year-old merchant sailor, be at fault for acting irresponsibly in time of war? Or did U.S. naval officers fail to provide that man with the charts and instructions necessary to safely enter Espiritu Santo’s harbor, then try to cover up their own negligence?

The SS President Coolidge was one of two nearly identical passenger vessels (the other being SS President Hoover) ordered by the Dollar Steamship Line on October 26, 1929. Construction began April 21, 1930, at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company in Virginia, and she was launched exactly 10 months later on February 21, 1931. Former First Lady Grace Goodhue Coolidge christened the new luxury liner with a bottle of spring water from their family farm, as Prohibition laws prevented the use of champagne.

Built at a cost of $7 million, President Coolidge measured 634 feet long with a beam of 81 feet and a 34-foot draft. Displacement was 30,924 tons. Turbine-electric Westinghouse engines propelled the vessel to a cruising speed of 20 knots, while her range exceeded 19,000 nautical miles.

President Coolidge, which struck a mine in the harbor of Espiritu Santo in October 1942.

The President Coolidge accommodated 990 passengers and a ship’s company of 324 crewmen. She could carry 600,000 cubic feet of cargo in her seven holds, one of which was refrigerated. Air conditioning, then considered an engineering marvel, kept travelers comfortable in tropical climes.

Entering service on October 1, 1931, SS President Coolidge plied the Trans-Pacific route between San Francisco and ports-of-call in Hawaii, Japan, China, and the Philippines.

During this tumultuous decade, crew members witnessed firsthand the global conflict then spreading across Asia. In June 1941, while transiting the Formosa Strait, President Coolidge’s lookouts counted 100 Japanese warships out on maneuvers there.

That same month, an agency known as the United States Maritime Commission assumed operational control of the President Coolidge. She would now serve as a troop transport, delivering U.S. Army personnel and their equipment to Far East garrisons. The liner, still manned by merchant seamen, made three journeys to Hawaii and the Philippine Islands under Army orders during the autumn of 1941.

When on December 7, 1941 (8 December west of the International Date Line), Japanese forces staged their surprise attacks on Allied forces across the Pacific, President Coolidge was en route to Honolulu from Manila carrying a number of American civilians and service dependents who had been ordered out of the Philippines. Stopping at Pearl Harbor, she took on a number of badly wounded servicemen for evacuation back to the mainland. The vessel reached her home port of San Francisco on Christmas Day.

Captain Henry Nelson, age 63, served as President Coolidge’s skipper. A seasoned mariner with nearly a half-century’s experience in the U.S. Merchant Marine to his credit, Nelson accepted this dangerous assignment—as he later wrote—“because of my feeling that my country needed me in its time of crisis.” Nelson and his vessel sailed continuously over the next nine months, transporting combat troops to Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and New Caledonia.

The President Coolidge’s final trans-Pacific passage began on Tuesday, October 6, 1942. At 1030 hours, she cast off from Pier 44 in San Francisco harbor and headed out to sea. On board were 340 ship’s crew, 50 U.S. Navy sailors, and 4,800 passengers—all members of the U.S. Army. Their artillery pieces, jeeps, trucks, camp equipment, and pallets of ammunition filled her cargo spaces. She also carried 519 pounds of quinine, the entire Pacific Theater reserve supply of this anti-malaria treatment.

Most of the soldiers on her passenger manifest belonged to the 172nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 43rd Infantry Division. Commanded by Colonel James A. Lewis, this formation included the 172nd Infantry Regiment, 103rd Field Artillery Battalion, a medical company, some combat engineers, and other service-support detachments. The 172nd RCT’s final destination was Guadalcanal in the Solomons, where U.S. Marines had been locked in a desperate fight against Japanese attackers for two full months. Lewis’ men would reinforce the American defense and ultimately help win victory on this island battleground.

Also present, but kept segregated from the 172nd’s troops, were 300 African American cannoneers serving with the 2nd Battalion, 54th Coast Artillery Regiment. A World War I veteran named Colonel Dinsmore Alter led this contingent and, as the highest-ranking Army officer embarked, acted as commander of troops throughout the journey.

Finally, Lieutenant Commander Craig Hosmer of the U.S. Navy headed President Coolidge’s 45-man armed-guard contingent. These sailors manned the one 5-inch, four 3-inch, and dozen 20mm antiaircraft guns mounted throughout the ship. Hosmer (who later became a U.S. congressman) was aided in his duties by Ensign Doran Weinstein and five Navy signalmen, who performed a variety of communications tasks.

The first leg of her journey, from San Francisco to the port of Nouméa in New Caledonia, lasted 12 days. She sailed without escort, as it was believed the President Coolidge’s 20-knot cruising speed was sufficient to outrun an enemy submarine. Frequent course changes also served to spoil a sub attack, although Nelson’s watch standers always kept a wary eye out for periscope wakes.

A routine of sorts quickly established itself among the GIs crammed into her holds. “Unless you’ve lived through it,” wrote 2nd Lt. James Renton of the 172nd RCT, “life aboard a combat-loaded Army transport is impossible to describe.” Renton tried anyway, detailing how his troops slept in canvas bunks stacked four-high: “Your pack was your pillow, your rifle your bunk mate, and duffel bags stowed along the bulkhead.” There was, he suggested, “at most, two feet between bunks.”

To prepare his ship for possible enemy contact, Captain Nelson insisted all hands participate in frequent fire and lifeboat drills. Lieutenant Hosmer’s armed guards also regularly test fired their deck guns. Yet there was time for fun, too. When President Coolidge crossed the Equator on October 12, her crew held a traditional “King Neptune’s Court” initiation ceremony.

SS President Coolidge docked at Nouméa, New Caledonia, on October 20, 1942. While most of her passengers debarked on a brief shore leave, the ship’s crew readied their vessel for her next port of call, Luganville Harbor on Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides.

The U.S. Navy’s port director at Nouméa, Lieutenant Commander John D. Andrews, closely managed all maritime traffic moving through his area of responsibility. On October 23, Andrews prepared President Coolidge’s sailing orders for Espiritu Santo. These documents defined her time of departure and route there, as well as other coordinating details. A set of attached special instructions, classified Top Secret, contained comprehensive directions on how to approach Luganville harbor. No mention of friendly minefields was included in any of Andrews’ instructions.

During the early afternoon of October 24, a harried young courier named Ensign John A. DeNovo boarded the President Coolidge carrying with him a satchel full of classified information. DeNovo was pressed for time. He had to hand Captain Nelson his sailing orders and depart the troopship so she could cast off as scheduled at 1500 hours. In his rush to complete this chore, the ensign may or may not have passed along all necessary documents. Nelson, for his part, signed DeNovo’s checklist indicating receipt of the detailed harbor entry directions, even though he later claimed these papers were never delivered.

Once underway, Captain Nelson and his First Officer, Kilton I. Davis, discussed how best to approach Luganville harbor. Having never docked there before, both men felt it would be safest to wait for a pilot—someone employed by the harbormaster who could help guide them through narrow Segond Channel. But the threat of submarines remained a concern. Standing outside the channel for any length of time, Nelson and Davis agreed, would just invite a torpedo attack.

President Coolidge arrived at Espiritu Santo shortly after sunrise on Monday, October 26, 1942. Halting at a rendezvous point three miles off Tutuba Island, Captain Nelson fretted while Ensign Weinstein’s signalmen attempted to contact a small warship seen circling some distance to the south.

This was the subchaser PC-479. It had been dispatched to guard the safe channel into Luganville earlier that morning when the destroyer normally assigned to perform this duty came in for fuel. Although PC-479 carried a harbor pilot, no one aboard knew that the President Coolidge was due to arrive or that she required navigational assistance. When the subchaser’s patrol track took it behind Tutuba, Weinstein lost his last chance to communicate with anyone who could help him safely reach port.

Ship’s time read 0906 hours. SS President Coolidge had been sitting exposed to enemy attack for over an hour with no sign of an approaching pilot boat. Nelson decided he had waited long enough and made for Scorff Passage, the normal peacetime route through Segond Channel. Unbeknownst to him, Scorff Passage was seeded with two parallel double rows of anti-submarine mines.

Signalmen on shore desperately flashed warnings to stop, and PC-479 took off at flank speed in a futile attempt to catch the errant transport before it met with catastrophe. These measures came too late; at 0935 hours a contact-fused sea mine went off under Coolidge’s keel. Seconds later, another explosion rocked the already crippled vessel. The blasts ripped two gaping holes in her port side; she began to list badly as seawater flooded in and fuel oil flowed out.

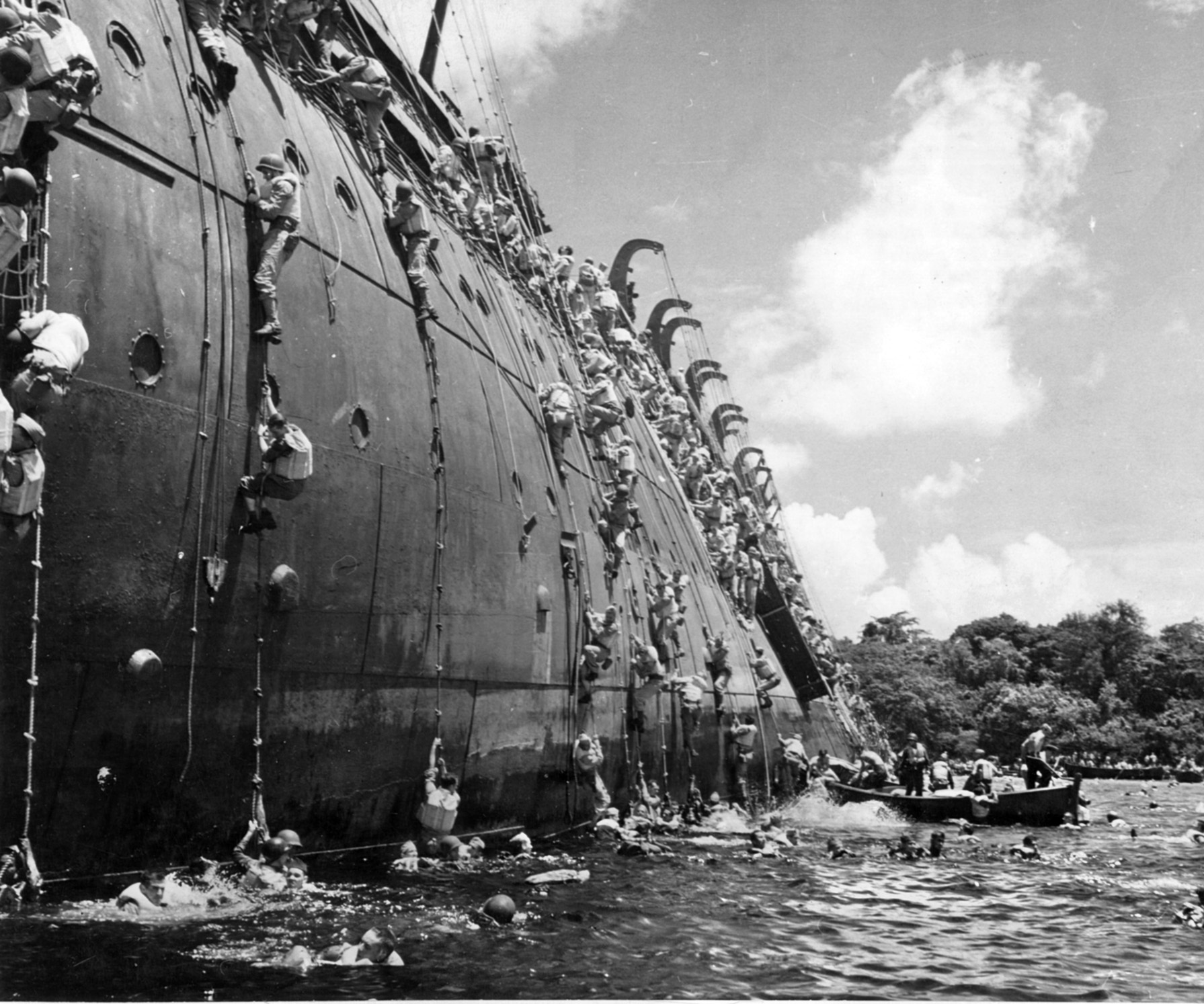

Captain Nelson immediately ordered a hard turn to starboard, attempting to beach his vessel before she sank. At 0938 hours, her bow hit a coral reef some 50 to 100 yards offshore, and the President Coolidge shuddered to a halt. Her passengers, prompted by loudspeaker announcements, donned their life jackets and prepared to abandon ship. Meanwhile, crewmen began lowering lifeboats and throwing cargo nets overboard to aid in the evacuation.

Infantryman Richard Schneider was, like many aboard, in his rack that morning. “When the ship hit the mine, I fell from the top bunk onto the floor. An alert was given, and we were told that the ship was not going to sink. We were instructed to stay in our quarters.”

Shortly thereafter, another voice informed him the transport was in fact going down. “We were instructed to leave,” Schneider recalled. “I made my way to the deck and jumped from the deck to a life boat.” He came ashore having “lost all of my equipment and personal belongings, escaping only with the clothes on my back.”

Lieutenant Renton remembered October 26 as “a beautiful, calm, and clear Monday morning.” After the explosions occurred, he heard the “call for all personnel to proceed to ‘Boat Stations’” and noticed the vessel was already “beginning to roll counter-clockwise.” Receiving orders to abandon ship, Renton and his platoon went “over the side—no panic, very orderly—all in life jackets, helmet liners, and web belt with canteen—into the warm Pacific.”

“Many boats were dispatched from shore to pick up survivors,” Staff Sergeant Parisi recollected. “It was organized chaos, but most of the soldiers stayed calm throughout the evacuation.”

At 1012 hours, Lieutenant Hosmer recorded that Coolidge’s list measured 18.5 degrees and was increasing one degree per minute. He then noticed several terrified G.I.s who refused to jump from the cargo nets and swim for shore. “Kick them in the face,” Hosmer shouted to other troops descending the nets. “She can’t stay up too much longer!”

Officers went from compartment to compartment, looking for anyone left behind. Army captains Elwood J. Euart and Warren K. Covill, together with Warrant Officer Robert H. Moshimer, struggled to locate the last groups of stray soldiers. Tying a rope around his waist, Euart crawled down a steeply sloped passageway while the other two men—bracing themselves against an outside hatch—held onto his safety line. It was now 1052 hours.

“The ship by this time had keeled over on the port side until the decks were vertical,” Moshimer wrote of that fateful moment. “At the same instant, the ship’s bow slid off the edge of the reef and sank stem first into the channel.”

Moshimer’s account continued: “Only seconds later the water came rushing up over us and in an instant we were carried down and down as the ship sank.” Moshimer could not recall how long he remained underwater, only stating that eventually “both Covill and I rose to the surface … but there was no sign of Euart.”

Captain Euart received a posthumous award of the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic sacrifice that day. Moshimer and Covill each earned the Soldiers Medal.

Although it was later learned that Fireman Robert Reid also perished in the blast, 5,438 passengers and crew did successfully escape the President Coolidge. One survivor, Private Henry Schumacher, summed up their feelings thusly: “Every man, though stripped of all belongings, felt thankful to be alive as he stumbled ashore.”

Once on dry land, however, these G.I.s faced a fresh set of difficulties. “We didn’t have a toothbrush. We didn’t have a tent. We didn’t have anything,” said the 172nd’s Sergeant Glen Goodall. “People on the island gave us what tents they could, and we lived that way for several months.”

Another castaway, Captain John H. Davin, described the motley appearance his fellow soldiers presented after a few weeks on Espiritu Santo. “Having lost most of their clothes in the sinking, the survivors had to wear whatever they could get from the various outfits ashore,” Davin wrote. “Soon, it became practically impossible to determine to which service a man belonged, for he may have had on Army, Navy, and Marine clothes at one time.”

The loss of SS President Coolidge and its cargo of war materiel demanded a thorough investigation. Within days of the incident, Vice Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, Jr., commanding the South Pacific Area, established a preliminary court of inquiry to gather information and recommend possible legal action. Beginning November 12, 1942, this court met on board the destroyer tender USS Whitney in Nouméa Harbor. Its members heard testimony for five days.

Yet the Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster. Shortly after the court rendered its recommendations, Halsey charged Nelson with gross negligence resulting in the loss of his troopship, two members of its company, and all government property aboard. Starting on December 8, 1942, a military commission convened in Nouméa to try him for dereliction of duty in wartime.

The proceedings lasted seven days and ended with Captain Nelson’s acquittal. His defense team, which included Lieutenant Hosmer, convinced the commissioners that those naval officers responsible for ensuring Coolidge’s safe passage from Nouméa to Espiritu Santo were to blame for its unfortunate demise and not the ship’s captain. Fully exonerated, Henry Nelson returned to California where in due course he received command of another large merchantman.

For months, the U.S. Navy suppressed all press coverage of SS President Coolidge’s last journey. When word of its sinking finally reached the public in December 1942, Americans reacted with shock and anger. Many people spoke out about the incompetence that led to this wholly preventable accident, as well as its impact on future military operations.

Indeed, someone had blundered.

Patrick J. Chaisson writes on a variety of historical topics from his home in Scotia, New York. He wishes to thank Lt. Col. Herman C. Brown, USMC (Retired), curator of the Vermont National Guard Library and Museum, for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments