By Charles W. Sasser

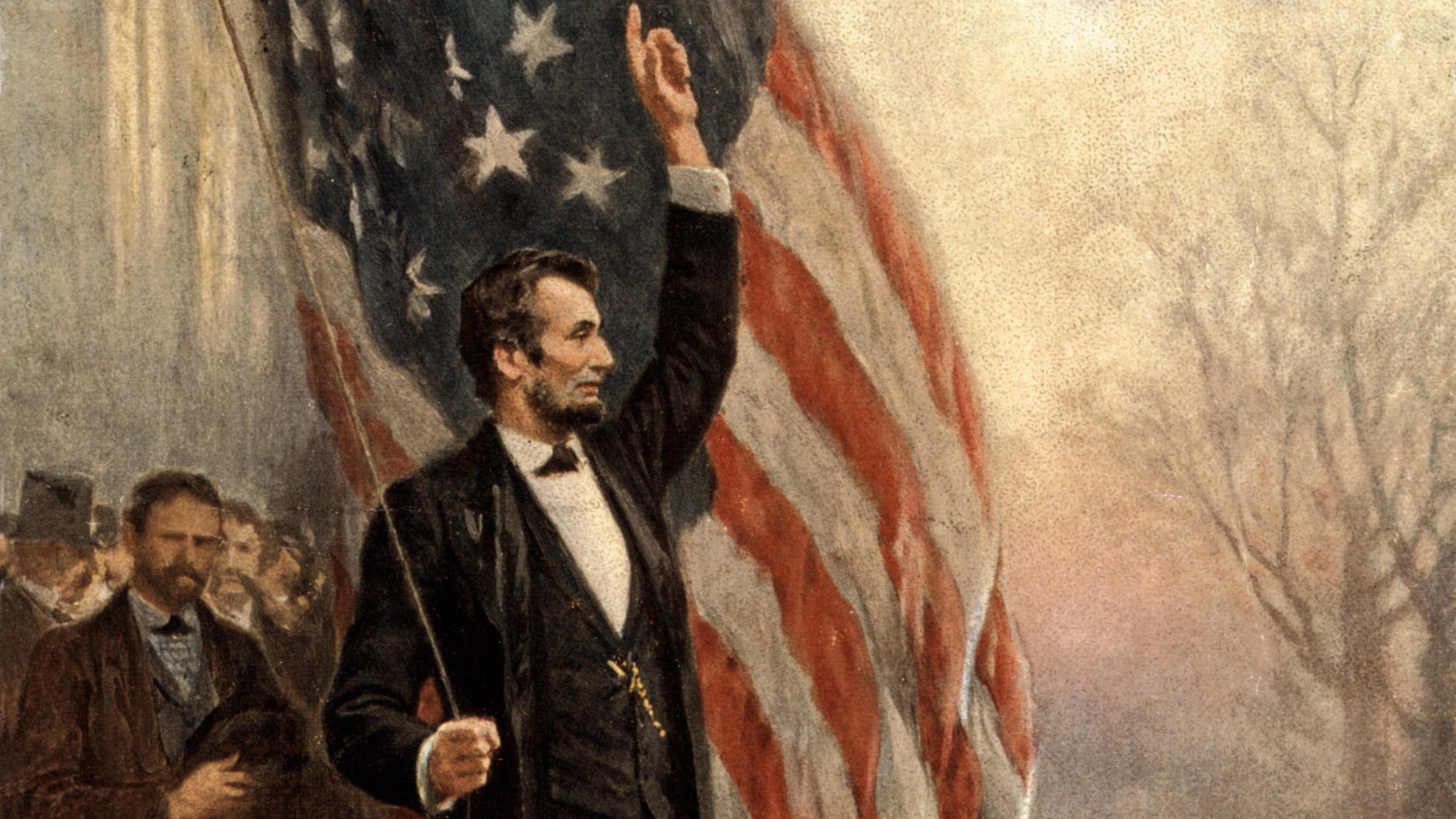

In the Academy Award-winning film Patton, the setting was all wrong when actor George C. Scott delivered General George S. Patton Jr.’s famous speech about making the “other poor dumb bastard die for his country.” The real Patton presented that speech on October 28, 1944, in France to the soldiers of the 761st Tank Battalion, nicknamed “Patton’s Panthers.” They were the first ‘Negro’ armored unit in the history of the U.S. Army to see combat.

The 761st had paused after a breathless dash most of the way across France for final checkups and repairs prior to battle when Patton’s entourage roared up. The general, wearing his notable ivory-handled pistols, vaulted to the hood of an armored car and shouted, “Men, you are the first Negro tankers to ever fight in the American army. I have nothing but the best in my army. I don’t care what color you are, so long as you go up there and kill the Kraut. Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Most of all, your race is looking forward to your success. Don’t let them down, and, damn you, don’t let me down. They say it is patriotic to die for your country. Well, let’s see how many patriots we can make out of those German SOBs.”

Desegregating the Draft: The Origin of the 761st Tank Battalion

Prior to 1940, assumptions about the inferiority of black soldiers as combat troops dominated military thinking. Blacks were segregated into support and service units to provide cooks, stevedores, truck drivers, orderlies, and other noncombat personnel. Only five black commissioned officers served in the Army in 1941, three of whom were chaplains.

“As fighting troops, the Negro must be rated as second-class material,” declared Colonel James A. Moss, commander of the 367th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division, “this primarily [due] to his inferior intelligence and lack of mental and moral qualities.”

“In future war,” said Colonel Percy L. Miles, “the main use of the Negro should be in labor organizations.”

Patton shared this view in a letter he wrote to his wife, Beatrice: “A colored soldier cannot think fast enough to fight in armor.”

Nonetheless, the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 stated, “In the selection and training of men under this act, there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race and color.” The White House immediately issued a policy statement saying that, regardless of the act, segregation in the armed forces would continue.

As war loomed on the horizon, all-black units commanded by white officers were quickly formed. Among these units were the 5th Tank Group, composed of three battalions of armor—the 761st Tank Battalion, the 758th, and the 784th. It was generally assumed that a white officer attached to a “colored” outfit was “safe” in that blacks would never be sent to war.

“Patton’s Panthers” Facing Discrimination

The 761st was activated at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, on April 1, 1942. Major Paul Bates, who had received armor training under General Patton, assumed command of the battalion in May 1943. His ambition was to lead his battalion into battle.

Major Bates became visible. He was always out in front, training with his men—in the swamps and in the mud and in the steamy Louisiana drizzle that made a man feel like he was bathing in a pot of Cajun gumbo. Morale improved. The battalion developed an esprit de corps. Black men held their heads higher and affected a cocky tanker’s walk with barracks cap tilted saucily to one side. Most still believed, however, that all the training was flash and polish toward no end.

“We ain’t gonna see nothing but rattlesnakes in Louisiana until this war be over,” said Private L.C. Byrd, whose comment was indicative of the sentiment that prevailed in the ranks of the black battalions.

Whites treated the black tankers with suspicion. The 761st tankers endured segregation down in “the swamp” where they were isolated from most facilities and had to walk a mile to the main gate and the bus station. Blacks waited until last to get on the buses when they received passes, and they always had to stand up at the back. Bus drivers wore pistols to enforce the rules and protect themselves from unruly blacks. If a black person failed to obey or committed some minor infraction, such as refusing to get up to let a white soldier take his seat, the driver stopped at the nearest MP station or law enforcement office where the offender was dragged away.

The 761st Black Panthers “Come Out Fighting”

The 761st Tank Battalion trained for over two years at Camp Claiborne and at Camp Hood, Texas, before it finally received orders for overseas movement on June 9, 1944, only three days after the Allies made the D-Day landings in Normandy. Three months later, the battalion departed New York aboard the British troop transport Esperance Bay, coming ashore in Britain on September 8. Initially assigned to the Ninth Army, it was reassigned on October 2 to General Patton’s Third Army.

According to a widely circulated story, Patton personally asked for the Black Panther Battalion, so-called because of the unit’s shoulder patch showing a black panther and the motto “Come Out Fighting.” Patton reportedly sent a message to the War Department requesting more tanks—the best available. The only tank unit left was made up of Negro troops.

“Who the … asked for color?” Patton shot back. “I asked for tankers.”

Fully armed, the 800-man 761st was equipped with 54 M4 Sherman tanks in three companies and a “mosquito fleet” company consisting of 15 smaller M5 Stuart tanks.

“Tommy Cookers” in France

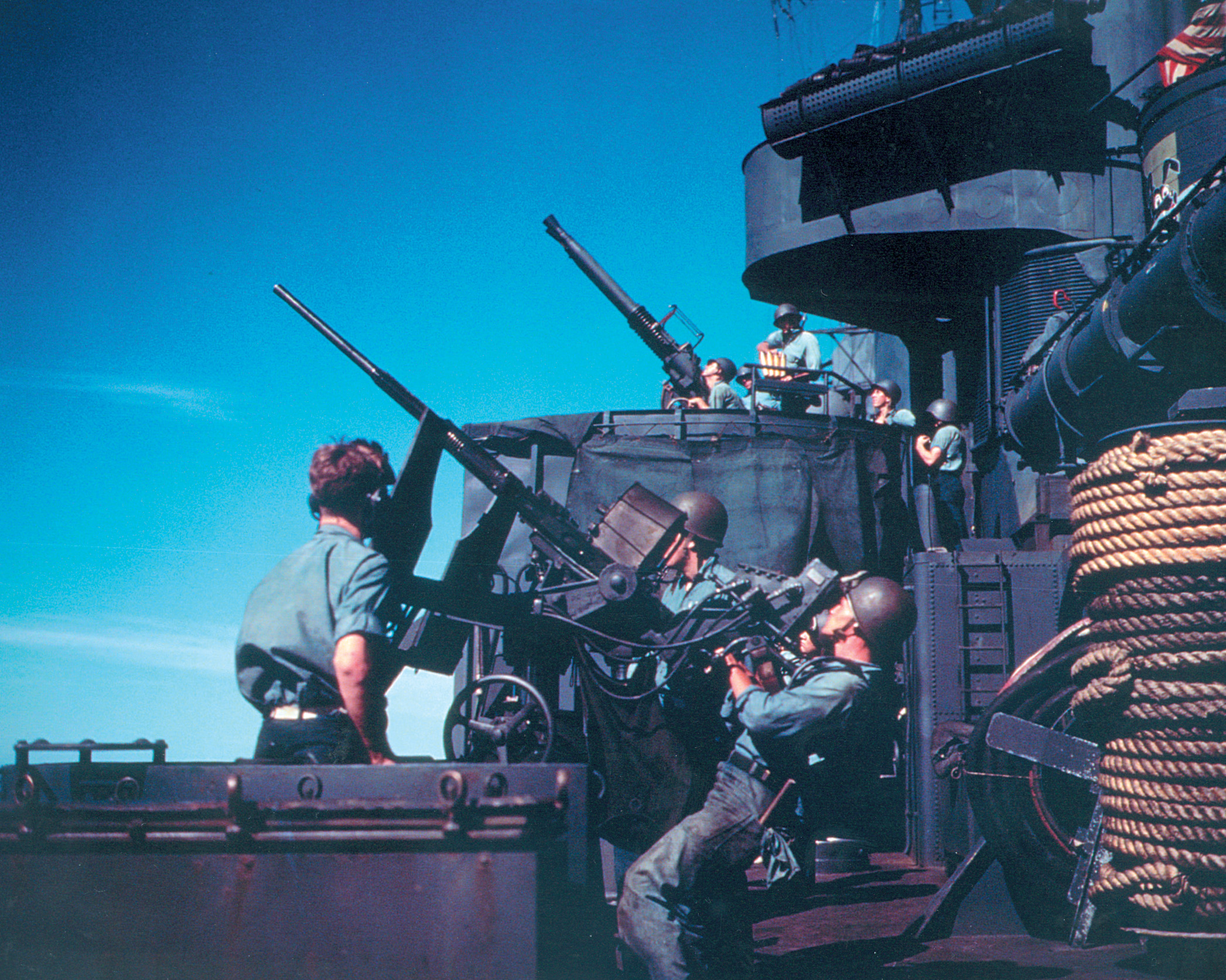

The medium Sherman main battle tank was the primary U.S. and British weapon when it came to armor. It was equipped with a 75mm main cannon plus two .30-caliber machine guns and heavy .50-caliber machine gun mounted on top of the turret. The nimble Sherman’s emphasis was on speed, mobility, and maneuverability. Powered by a 450 horsepower V-8 gasoline engine, it weighed 35 tons, including its five-man crew, and could reach speeds of nearly 30 miles per hour over a range of 100 to 150 miles.

Although the Sherman was faster, more reliable, and could fire at a faster rate than its enemy counterparts, the German Panther and Tiger tanks commanded greater accuracy and range with their main 75mm and 88mm guns. German armor was thicker, the tanks had wider tracks, and they burned diesel rather than gasoline fuel, which made these tanks less likely to explode and burn when hit. The British nicknamed the Sherman “Ronson” after the American cigarette lighter, which advertisements had claimed, “Lights the first time every time.” The Germans called the Shermans “Tommy Cookers.”

Patton’s Panthers landed in Normandy on October 20, 1944, and dashed 400 miles across France in six days to catch up with Patton at Nicolas de Port. The Black Panthers were detailed to link up with Maj. Gen. Willard S. Paul’s 26th Infantry Division as the Allies continued to squeeze an iron ring around Germany from every direction. It was a week before the attack on the fortress city of Metz that General Patton delivered his famous pep talk to his newest tankers. As he finished and climbed down from the hood of the armored car, he noticed young Corporal E.G. McConnell standing at attention.

“Listen boy,” Patton growled, “I want you to shoot every damn thing you see—church steeples, water towers, houses, old ladies, children, haystacks. Every damn thing you see. This is war. You hear me, boy?”

Corporal Howard Richardson turned to his company commander, Captain David Williams: “Sir, that old man is crazy as hell,” he said. “Did you see the way his eyes roll around when he talks? That’s no bullshit about him being a hornet. I’m more afraid of him than I be of them Krauts.”

First Casualties of the 761st

The rumored “big offensive” against entrenched German defenses kicked off at dawn on November 8. The 26th Infantry, with Patton’s Panthers attached, would fight in the same sector where it had fought in 1918—on ground south of Chateau-Salins through Moncourt Woods to a hill northwest of Chateau-Salins. Opposing it were the German 11th and 13th Panzer Divisions.

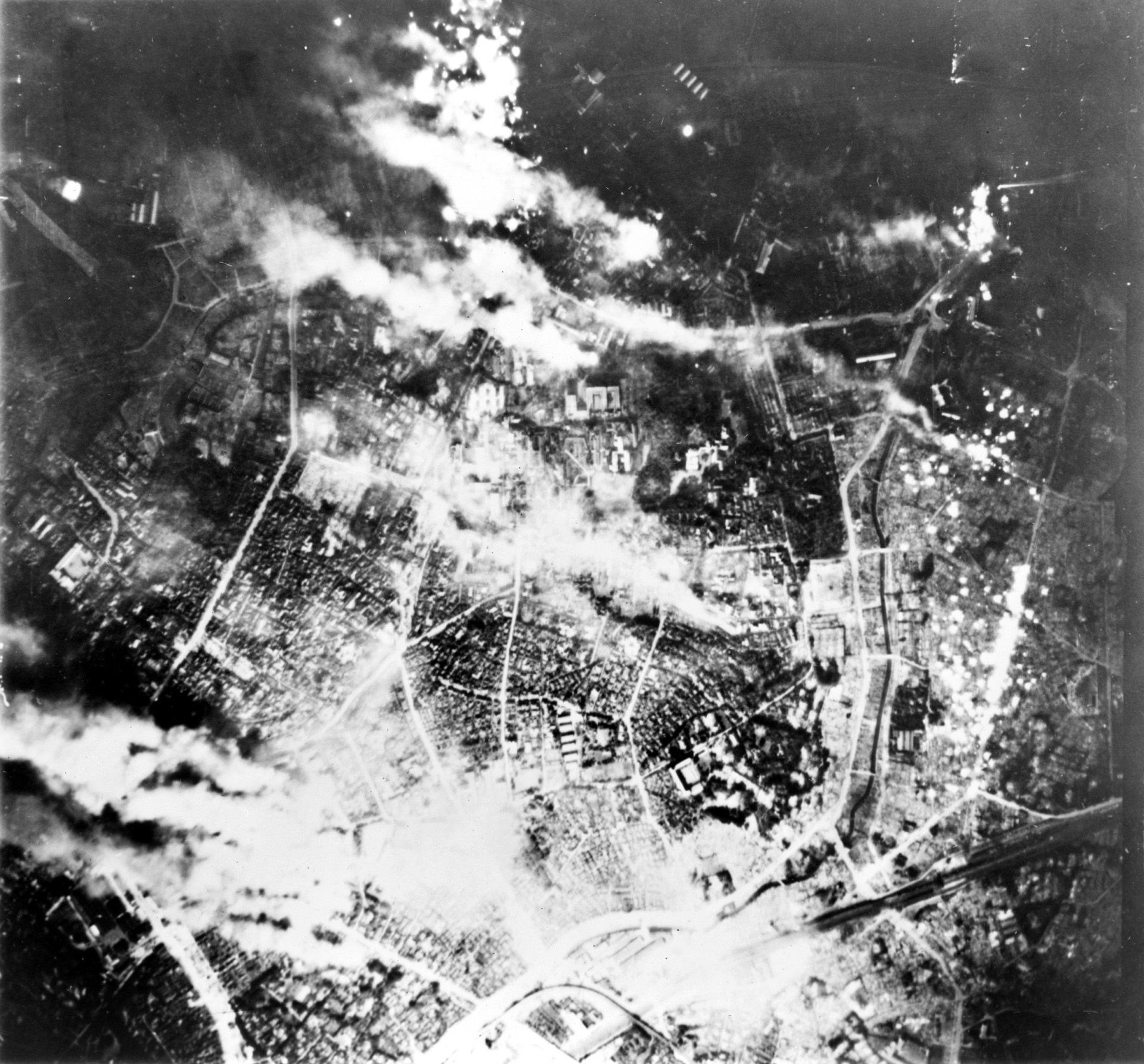

Repeated Allied bombing had cracked the Dieuze Dam, flooding the valley of the Seille River and low-lying areas. The terrain was treacherous, and the area was a thoroughly miserable place for a battle. The duel began with the ear-piercing shriek of a German 88. Artillery explosions walked mushrooms of smoke across the lowlands as the Germans attempted by sheer weight of numbers and ferocity to knock off attacking American infantry and supporting tanks.

Captain Williams’s cheery voice broke onto his company’s radio band, speaking “Harlemese” although he, like most commanding officers at this time, was white: “Now, looky here, ya cats. We gotta hit it down the main drag and hep some of them unheped cats on the other side. So let’s roll on down de Seventh Avenue and knock ‘em, Jack.”

An aid man with a medical detachment in the rear of the formation, rather than a tanker, became the battalion’s first soldier killed in action. Private Clifford Adams was rendering aid to a wounded G.I. when a shell landed almost on top of him. No one expected him to be the battalion’s first casualty.

Other events unfolding in the rear would affect the Black Panther Battalion as profoundly as anything the Germans threw at it on the assault line. While the fury of the opening battle rolled like thunder all along the length of the front line, a small enemy patrol crept through woodland thickets to where Colonel Paul Bates stood on the hood of his Jeep watching the fight. Submachine gun bullets splattered into the Jeep. A slug caught the colonel, knocking him, seriously wounded, to the ground. The commander the Panthers had trusted and depended on, who had developed their pride as a fighting unit, had fallen on the first day of battle.

A tanker called Smitty transported executive officer Major Charles Wingo to the front to assume command. Wingo did not last long. Smitty got out of his tank.

“Where’s Major Wingo?” Corporal E.G. McConnell asked. “He went nuts,” was the response. “He might not be plumb chicken, but he sure got henhouse ways. He gets out and looks down there and starts shaking all over like a stray dog passing razor blades in the rain. He took off in a Jeep to the rear.”

First, the colonel was seriously wounded. Now, the executive officer had deserted his men in combat, leaving the battalion without leadership when the men needed it the most. Although Wingo had not yet seen combat, he was evacuated for “combat fatigue” and never seen again. Lt. Col. Hollis E. Hunt transferred from another battalion to assume command..

The Heroic Sam Turley

In spite of some of the detrimental assessments of black soldiers in combat, the Black Panthers distinguished themselves almost immediately, even though they were not expected to perform as valiantly as white soldiers. During the approach to Morville, Charlie Company’s tanks got bogged down behind a cleverly concealed antitank ditch 15 feet wide, four feet deep, and studded at the bottom with steel spikes. It was snowing heavily, and devastating mortar and artillery fire rained down on the exposed assault force. Buried mines erupted in a broad, deep swath among the American tanks and soldiers. Tracers cracked and wove designs across the white field. A number of tanks were hit in the initial volley of enemy fire. Several blazed brightly.

Tankers abandoned broken mounts and headed toward the rear, helping each other, dragging or carrying wounded. Others scrambled into the freezing muddy water at the bottom of the antitank ditch, which was soon filled with marooned and wounded tankers and infantrymen.

First Sergeant Sam Turley’s tank was one of the first hit. Realizing that the soldiers trapped in the ditch were doomed unless they escaped right away, Turley ran up and down the ditch shouting for soldiers to head uphill toward higher ground where they might find cover. The last anyone saw of Turley, he had jumped out of the ditch to provide covering fire for escaping soldiers. He stood straight and tall behind the ditch, snow swirling around him, ammo belts thrown over his shoulders, a spitting .50-caliber machine gun held close to his hip to absorb its recoil.

Turley continued to shoot until German counterfire ripped into his body. As he crumpled to earth, his finger froze to the trigger, and the gun continued to bang. A direct hit from an 88mm shell killed him outright.

“We Got a Job to do”

Suffering heavy casualties, the men of the 761st drove on toward Metz, rough going against rain, mud, cold, snow, driving sleet, and a determined enemy. Sergeant Ruben Rivers, a farm boy from Oklahoma and now a tank commander, got out of his machine under heavy fire to attach a cable to a section of dragon’s teeth obstacles and pull it out of the way so his platoon could proceed. A day or so later, a mine detonated underneath Rivers’s tank and shredded the flesh of his leg. Medics cleaned and dressed the wound and attempted to administer morphine for pain. Rivers pushed them away and refused to be evacuated.

“Captain, you’re going to need me,” Rivers assured the Able Company commander, Captain David Williams. “We got a job to do.”

Wounded though he was, Rivers led an echelon of tanks that blazed its way into a small village blocking the approach to the important rail and communications center of Guebling.

“Don’t go into that town, Sergeant!” Rivers’s platoon leader radioed. “It’s too hot in there.”

“Sorry, sir,” Rivers responded. “I’m already through that town.”

Rivers lost a second tank the next day. He commandeered another tank and remained in the fight. That night, a medic warned the sergeant that his wounds were getting gangrene. Rivers still refused evacuation.

“Tomorrow’s going to be tough,” he asserted. “Another day won’t make any difference.”

Fighting continued in and around Guebling. By dawn of the third day of battle, Rivers and his crew had destroyed at least two enemy tanks and killed over 300 Germans. Mark IV panzers and several German tank destroyers rumbled out of the fog. “I see them!” Rivers radioed. “I’ll fight them!”

Outnumbered and outgunned, Rivers and Technical Sergeant Walter James darted their two Shermans from cover and fought a delaying action that allowed Americans caught in the open to withdraw and regroup. A shell finally caught Rivers’s tank and cracked it like an egg shell. A second armor-piercing shell finished the job. The tank commander who refused to withdraw was dead.

Rolling Up the Maginot Line

The enemy continued to bitterly contest every inch of ground. Third Army units spearheaded toward the Maginot Line and, beyond that, Germany’s Siegfried Line. Black Panthers learned to live with war and its constant dangers. It was more terrible than anything they could have imagined.

Combat stripped away the everyday business of skin color, religion, and social class. White soldiers and black soldiers lived together, or at least side by side, in a common condition of discomfort and danger. Only in rear areas was race an issue.

After Corporal E.G. McConnell was wounded at Honskirch, he was evacuated to a field hospital where he was the only black man. One day, a major general paid a visit to cheer up the heroic wounded. He paused when he reached McConnell and asked in an attempt at humor, “What’s wrong with you, boy? Got the claps?”

The remark, an echo of an old stereotype pertaining to supposed black promiscuity, cut McConnell like a rapier. He turned his head away and lay there in humiliation. He could hardly wait to get back to the front line. It may have been precisely because of such stereotypes and because of low expectations from white observers that Patton’s Panthers became determined to prove they were warriors equal if not superior to their white comrades in arms.

Allied forces hit the French-built Maginot Line, now garrisoned by German troops, on December 9, 1944, and pushed through the defenses. The 761st rolled onto German soil. Sergeant Willie McCall got out of his tank and looked around. “So this,” he said, spitting contemptuously, “is the home of superman?”

To Relieve Bastogne

At precisely 5:30 am on December 16, 1944, an American sentry in the quiet Ardennes Forest radioed headquarters to report innumerable “pinpoints of light” suddenly flickering all along the German line. The “pinpoints” were the muzzle flashes of hundreds of German artillery pieces. The ensuing roar and concussion of the German guns were the opening shots of Hitler’s desperate Ardennes Offensive, which resulted in the Battle of the Bulge.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, ordered Patton to break off his advance in the Saar and turn northward to relieve the besieged town of Bastogne, which was astride a key crossroads. The 761st, now commanded by Major John F. George, received orders to dash to the Ardennes with the rest of the Third Army. The 761st was assigned to support elements of the 87th Infantry Division in the recapture of the village of Tillet, which was located some 15 miles west of Bastogne and less than three miles from the Marche-Bastogne Highway, a major German supply route.

Fighting along broken roads and trails, the 761st and the 87th plowed through heavy opposition to cover the 25 miles toward Tillet during six days of combat. The Germans fought savagely to hold their ground, exacting a high price in American casualties.

The elite Begleit Brigade of the 13th Panzer Division, whom the Black Panthers had fought earlier in the Saar Basin, waged a grueling defense in the dense pine woods south and east of Tillet. Enemy fortifications were carefully planned and backed by numerous machine gun nests, self-propelled guns, mortars, and armor. Allied tanks, artillery, and infantry tried to take Tillet and end the seesaw battle to win the St. Hubert Road. All had failed, beaten back by stubborn German defenses.

“I Say We Fight it Out”

On the night of January 4, 1945, Captain David Williams of Able Company sent a runner back to Major George with a message that he feared the Germans might have surmised that his men were short of supplies and that they could launch a counterattack. He was not sure that Able Company could hold on if attacked in force. Williams was to have been reinforced by airborne units that had not yet arrived. George responded for Able Company to hold its ground and then to launch an attack of his own to capture Tillet the following morning.

Williams gathered his platoon leaders and noncommissioned officers in a house in the village of Gerimont. “I’m not going to mince words,” he said, looking as tired, ragged, filthy, and unshaved as the other men in the room. “If the Germans attack us, we can’t hold them. I guarantee you that if we resist, they’ll kill us all. I’m the company commander, but I’m going to bow out of this one. This is one decision you guys have got to make. Do you want me to wave my underwear or do you want to fight it out?”

For a long minute no sound came except the low moaning of the winter wind. Finally, Sergeant Walter Lewis slapped his coffee cup on the table and stood up. “We can’t give up, captain,” he said. “It wouldn’t be right. I say we fight it out.”

That broke the tension. Nervous laughter filled the cottage, and the vote was unanimous. “Done!” Captain Williams concluded. “If Walter wants to fight it out, then we’ll fight it out.”

Axis Sally and the “White Man’s War”

To Williams’s relief, the airborne reinforcements arrived overnight, pulling into Gerimont over snow so frozen it cracked and popped under the pressure of the vehicles. The German counterattack failed to materialize. The first action against Tillet was launched at dawn. As tankers crept through early morning fog and snow, Axis Sally jammed American radio transmissions with her propaganda.

“Good morning, Negro soldiers of the 761st,” she crooned. “I am sorry that you will die today in Tillet. Our fight is not with the Negroes in America, and your fight is not with us. Your fellow Negroes are rioting in Cleveland. Your commander, Captain Williams, is leading you to death and destruction. He is white and not one of you. Your battalion commander, Major George, is also white and not one of you. Leave your tanks now and return home to Cleveland where you are needed and you will not be killed.”

Axis Sally played Louis Armstrong’s “I Can’t Bring You Anything But Love, Baby” to accompany Patton’s Panthers into combat. During the fighting, notable for its raw savagery, it was never clear at any moment to the men of the 761st whether they were winning or losing.

“They’ve hit me three times!” tank commander Frank Cochran responded to an inquiry, “but I’m still giving ‘em hell.”

Crusty Captain Charles “Pop” Gates of the 761st personally led a successful 10-tank assault on a German-held hilltop outpost that proved to be the last obstacle to taking the town. Tillet finally fell on January 7, 1945. A German prisoner seemed stunned to see black men in uniform. “What are you doing here?” he asked Sergeant Johnny Holmes in English. “This is a white man’s war.”

Sergeant Holmes offered him a cigarette. “You ain’t got no black or white when you’re over here and the nation is in trouble,” he replied. “You only got Americans.”

Colonel Bates had promised to return after being wounded during the battalion’s first day of combat. He kept that promise and resumed command of the 761st on January 17. The battle-hardened battalion had changed considerably during his absence. Many of the old timers from the days at Camp Claiborne and Camp Hood were gone, some of them dead and many of them wounded. Over 30 percent of the outfit had been replaced since November.

Breaking the Siegfried Line

After the Battle of the Bulge, the Black Panthers received orders to proceed to Saverne, France, and temporarily attach to the Seventh Army to break through the Siegfried Line. That fight began on March 20, 1945, and was a slugfest all the way.

The Germans had placed pillboxes and camouflaged artillery and machine guns in the woods and in the fields on both sides of narrow roads leading to key towns. Sherman tanks confronted the enemy head-on, while soldiers hastily dismounted whenever the columns encountered opposition and moved up through the high ground to root out the enemy infantry.

The important town of Silz occupied a vital crossroads at the bottom of a gradual decline. Charlie and Baker Companies, led by Captain Gates and Captain Johnny Long, were assigned to support infantry in capturing it. Artillery fire touched off a German ammunition dump, which erupted in a spectacular explosion and set the town afire. Flames licked back at the darkness as tanks led the attack, sweeping in so fast that German antitank positions were caught by surprise and captured without firing a single shot.

As Americans stormed into one side of the blazing town, a German column of at least 100 trucks, horse-drawn artillery, and antitank guns fled out the other side. Hitler’s armies were abandoning the Siegfried Line and running for their lives. This was a rare opportunity to trap significant numbers of enemy troops and capture or annihilate them. Blood lust boiled through the veins of the men whose only thought was to pay back those who had been killing and wounding their comrades for months.

The tanks of the 761st caught up with the Germans where the road twisted into a series of S curves, devastating the enemy column. Debris, dead horses, shattered guns, artillery pieces, and vehicles were burning along the road, and dead enemy soldiers littered the scene. Bates ordered tank dozers forward to clear the road.

Crossing the Rhine

As part of Task Force Rhine, the 761st Tank Battalion crossed that great river in March. During the fight to the last great natural barrier on the German frontier, the tankers had destroyed 31 pillboxes, 49 machine gun emplacements, 29 antitank guns, and 11 ammunition trucks. Twenty antitank guns and seven towns had been captured, while 833 Germans had been killed and 3,210 taken prisoner. Five American tanks had been lost, and 300 tons of ammunition had been expended.

On March 30, 1945, the battalion arrived in Langenselbold, Germany. The end of the war seemed in sight. Patton’s Panthers began a drive across the Reichland, cruising the Autobahn, overrunning airfields, and firing on enemy troops hidden along the highway. Refugees were always present, and the gaunt, gray-clad prisoners trudged toward the rear.

Charlie Company of the 761st captured Vehlenstein Castle in Neuhaus, Germany, reinforcing the G.I. belief that the war was nearly over. Hitler’s Luftwaffe chief, Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, had claimed the castle when the Nazis came to power and stored in it many priceless art objects that had been looted from occupied territories.

It was inevitable that advancing American troops should also begin encountering Nazi concentration camps during their rapid push across Germany in the spring of 1945. Most of the men of the 761st did not know the camps existed until one morning when elements of the battalion drew up before a labor camp surrounded by barbed wire. Stunned tankers climbed out of their vehicles and gazed at sights of unspeakable horror.

On April 28, 1945, Radio Milan announced that Italian Fascist Dictator Benito Mussolini had been executed by communist guerrillas. Two days later, Hitler and his mistress, Eva Braun, committed suicide in their Berlin bunker. The 761st Tank Battalion reached the city of Steyr, Austria, on the banks of the Enns River, on May 5, 1945. Over 100,000 German soldiers, fleeing the advancing Soviet Red Army, surrendered to American troops, who herded them into a large field that had become a makeshift holding facility.

130,000 Axis Casualties

By the end of the war, the 761st Tank Battalion had been in combat for 183 continuous days. During this time, it participated in four major Allied campaigns in six different countries and was attached to three separate American armies and seven different divisions. The Black Panthers had inflicted more than 130,000 casualties on the enemy. Eight black enlisted men received battlefield commissions, while 391 received decorations for heroism, including one Medal of Honor awarded posthumously to Sergeant Ruben Rivers, seven Silver Stars, three of them posthumous, 56 Bronze Stars, and 246 Purple Hearts. Three officers and 31 enlisted men had been killed in action, and 22 officers and 180 enlisted men had been wounded. In 1998, the 761st Tank Battalion received a much delayed Presidential Unit Citation.

On VE Day, tanks of the 761st lined up beside a small bridge along the Enns River. General George S. Patton Jr. stood up in a Jeep, tall and straight. The soldiers of the 761st saluted smartly. The general returned the salute and drove on. The great warrior wore a quiet, satisfied look on his face. He had asked for the best tankers, and he had gotten them.

Charles W. Sasser is a veteran of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Special Forces. He resides in Chouteau, Oklahoma.

Thanks for all the research. Very interesting and informative. This “Black Panther” history is not taught in schools or in the media.

Why hasn’t anyone made a movie about the 761st black Panthers tank battalion it would be as great as or ever better than The Red Tails in my opinion ,comments yours in reply Don Jones

The screen play was Awful, the lead characters were British (They spent more time trying to “Sound like Black Americans, than actually ACTING.”). I would rather “Listen” to the Actual Tuskegee Airman, than watch to that boring, adventureless, uncaptivating, horrible, unpatriotic, unheroic movie! Their Documentaries are more Courageous and Honorable.