By John Brown

In September 1942, two patrols of armed jeeps and trucks of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) raided the German airfield at Barce. Between Benghazi and Derna in Libya, Barce was 550 miles behind the El Alamein line where German General Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Army Afrika was shaping up for a battle with British General Bernard Law Montgomery’s Eighth Army.

German and Italian planes were assisting Rommel and bombing the island bastion of Malta in the Mediterranean. In the sharp, short raid, the LRDG patrols set 24 planes on fire, damaged another 12 with bombs and machine-gun fire, and destroyed 10 trucks and a fuel tanker and trailer. An unknown number of German and Italian soldiers and airmen were killed or wounded.

It was just a pinprick for the Axis forces, but with other raids by the LRDG and SAS (Special Air Service) deep in Axis-held territory it forced the Germans and Italians to beef up their rear-area security when Rommel needed all the troops he could find for the Alamein front.

With the raiders at Barce was an observer and guide, Major Vladimir Peniakoff. In the raid he had a finger smashed by a bullet; the finger was amputated next day in the desert and at the same time some shell splinters were taken from one of his legs. However, he said, he “enjoyed himself thoroughly” and was determined to have his own independent unit operating along the lines of the LRDG and SAS.

The Oldest 2nd Lieutenant in the British Army

Vladimir Peniakoff was born in Belgium in 1897 of wealthy émigré Russian parents. He was a brilliant student and began studying engineering, physics, and mathematics at the University of Brussels at age 15. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, he was sent to England where he continued his studies at Cambridge University, but not for long. He went to France and worked in a factory until accepted for the French Army in which he saw some action with the artillery and was wounded. When World War I ended, he returned to Belgium to manage his father’s chemical factory for research and production of aluminum.

In 1924, unhappy with life in Belgium, Vladimir took a job as an engineer with a large, French-owned sugar company in Egypt, and for the next 15 years he filled various posts within the company in Cairo and in Upper Egypt. In his spare time and on holidays he made expeditions into the desert in a Model A Ford, where he made friends with Arabs he met, learned to navigate in the wilderness, and learned something of desert lore. In 1928 he married a Belgian woman, Josette Ceysens; they had two daughters and divorced in 1942.

When World War II began in 1939, Peniakoff was 42 years old, a square, powerfully built man of complex character, moody, explosive, intolerant, loyal, a man of many contrasts. He was, one LRDG officer said, “often muddle-headed” and “had become very Arab in his ways, particularly in relation to time.” He was a great admirer of the British way of life and immediately volunteered for the British Army. As Belgium was still neutral and he was Belgian, he was not accepted. But when Belgium was invaded, he was accepted and commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the general list, probably the oldest 2nd lieutenant in the British Army.

The Making of Popski’s Private Army

By a mix of bluff, persistence, and some lies, he got himself appointed a company commander in the Libyan Arab Force. With it he saw some action around Tobruk, and in May 1942 he was given command, as a major, of a detachment to be known as the Libyan Arab Force Commando.

It was a small unit of 22 Senussi Arabs, a British sergeant, and an Arab officer—an independent command—and it had no transport. For that and his supplies, he had to rely on the LRDG. For five months he operated behind the Axis lines in the Jebel Akhdar, the lushly forested and mountainous area between Benghazi and Derna in Libya, keeping a road watch and reporting Axis traffic along the coast, rescuing shot-down airmen, and ambushing when he could.

In one action, Peniakoff destroyed a large, 450,000-gallon fuel dump. Then, with Rommel nearing the gates of Alexandria, the LRDG was pulled back from its forward base at Siwa and with it Peniakoff and his Commando. The Commando was disbanded in a reorganization of the Libyan Arab Force, and Peniakoff went to see Colonel Shan Hackett in Cairo.

Hackett controlled all special forces in the Middle East. He had read a report on irregular warfare that Peniakoff had written and knew of his work in the Jebel Akhdar—and he was a very perceptive man. He suggested that as Peniakoff knew the area very well he should accompany an LRDG raid scheduled on the airfield at Barce, and while Peniakoff was away he would think of something for him to do.

After the raid on Barce and after a few days in the hospital, Peniakoff went to see Hackett. Hackett authorized him to set up a small, motorized unit to go behind enemy lines to find and destroy fuel dumps, aircraft, and transport. The unit would have an establishment of one major—Peniakoff—a captain, three lieutenants, and 18 other ranks. It would have six vehicles and would be called No. 1 Demolition Squadron; it would be the smallest independent unit in the British Army.

Peniakoff was not satisfied with the title of the unit, and Hackett suggested “Popski’s Private Army (PPA).” Popski was the name given to Peniakoff by the LRDG New Zealanders when they found Peniakoff too much of a problem in radio transmission. Peniakoff agreed, had some “PPA” shoulder flashes made and some cap badges in the form of a 16th-century Italian astrolabe, and went off to find recruits, vehicles, weapons, and equipment.

Raiding Behind the Mareth Line

Popski’s first recruits were old comrades from the Libyan Arab Force: a Scot, Captain Bob Park Yunnie, and a French lieutenant, Jean Caneri, who would be released from his duties with the force when possible. He filched a Sergeant Major Waterson from the King’s Dragoon Guards (an armored car regiment), a ferocious looking one-eyed Corporal Locke from the LRDG, a young surveyor named Petrie from a survey unit, and several drivers from the Royal Army Service Corps.

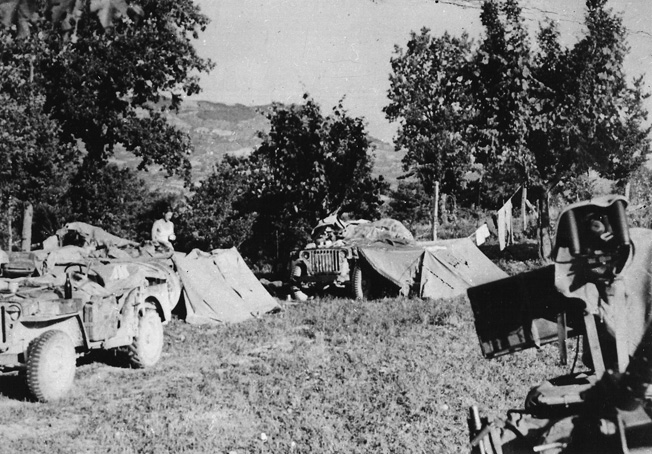

When it left Cairo in October 1943, Popski’s Private Army consisted of Popski, Captain Bob Yunnie, 12 other ranks, and three Arab soldiers from the Libyan Arab Force. They drove out in four jeeps armed with twin Vickers .303 machine guns and two three-ton trucks loaded with 11 days’ rations, more than a ton of explosives, and fuel for 1,500 miles. They headed for the LRDG’s base at Kufra.

After the inevitable breakdowns and other delays normal in desert travel and getting lost in the Great Sand Sea, when PPA reached Kufra they found that Montgomery’s Eighth Army had already pushed Rommel back to Tripolitania (i.e., western Libya, out of Cyrenaica and the Jebel Akhdar in eastern Libya). Popski decided he must move to Tunisia to get behind Rommel’s lines.

He knew, however, that Tunisia would be a very different battleground from the Jebel Akhdar. Travel without being spotted would be much more difficult, and enemy airfields, fuel dumps, and convoys would be much better protected. Popski’s men needed more training, and for this he took them to the LRDG’s base at Zella. At Zella, Lieutenant Jean Caneri joined him. Caneri, a lawyer before the war, took charge of PPA’s administrative affairs and proved a great asset.

Training with the LRDG was “on the job.” On one occasion Popski took his men out with a patrol of the LRDG to find a route by which Montgomery’s armor could outflank the Mareth Line. They did find a route, but while Popski and three jeeps were away from his base camp on reconnaissance, the camp was betrayed by Bedouin and attacked by German Messerschmitt fighters. All vehicles and stores were destroyed, and two New Zealanders of the LRDG were badly wounded.

The only transport vehicles left were the three jeeps that had been away from the camp. Popski rushed them off with the wounded to Tozeur, 200 miles away through enemy territory, while the others walked. They had almost reached Tozeur when they were picked up by Henry’s Patrol of the LRDG and taken to Tozeur.

From there, Popski took his men to Tebessa, Algeria, where he persuaded the American II Corps to issue them rations and clothing. While they were at Tebessa, publicity was given to their journey through the dangerous gap between the German and American armies, and Popski seized the opportunity to get PPA transferred from the British Eighth Army to the British First Army.

From the American area, he led his men on raids against the Axis forces north and west of the Mareth Line. In jeeps, each armed with a .30-caliber and .50-caliber Browning machine gun, they raided airfields and shot up aircraft, ambushed convoys, and did as much damage as they could until the war in North Africa ended. They accounted for many vehicles, aircraft, and supplies and sundry other items including 600 Italian prisoners. Of more importance was the confusion the tiny force caused the Germans and Italians.

The PPA in the Invasion of Italy

During the four months prior to the invasion of Italy, Popski recruited more men from various units. He had everyone undergo training with the SAS. His standards were exacting. While discipline within PPA was loose—officers and men lived together and shared everything, saluting was optional, the word “sir” was rarely heard, the men wore whatever pieces of uniform or civilian clothing they preferred, provided they didn’t include any items of enemy uniform, and Peniakoff was “Popski” to everyone—he demanded resourceful, fighting men. Any man who did not come up to, or fell below, his standards was sent back to the unit he came from. Not that there were many; Popski had an uncanny ability to pick the right kind of man for his kind of war.

The majority of volunteers for PPA were rejected at interview. Popski picked men who were well trained in all the basic military skills, were good cross-country drivers, and above all were resourceful and showed initiative. Once accepted, a recruit underwent a grueling training program that included navigation, signals, and demolition.

For the invasion of Italy, PPA was attached to the British 1st Airborne Division, and Popski had his men trained to take their jeeps and equipment in by gliders. But then the 1st Airborne Division was sent in by sea to the port of Taranto on the heel of the boot of Italy, and Popski and a patrol of five jeeps landed with the advance elements of the division on September 9, 1943.

Italy had signed an armistice with the Allies two days before the landing, and although the landing was unopposed the military and political situation ashore was very confused. The Germans, considering the Italians traitors, were occupying more Italian territory, and information on German strength and activity in the Taranto area was urgently needed. While the 1st Airborne set up a defense perimeter around the port, Popski took his jeeps off to find answers and locate possible landing grounds for the Royal Air Force between Taranto and Brindisi.

Popski was back 30 hours later to report that the Italian armed forces in the area were either friendly or apathetic, and although they would not take up arms against their former German comrades, they would do nothing to hamper Allied forces. He had all the information the RAF needed about landing areas, which he had obtained from Italian Air Force officers. He had not seen any Germans and could get no information on them.

Popski’s Reconnaissance Coup

The task of the 1st Airborne at Taranto was to ease pressure on the American Fifth Army at Salerno, but before leaving Taranto the lightly armed airborne troops, without air, armor, or artillery support, needed to know enemy positions and strength.

Popski drove to Bari where he found a very jittery Italian corps commander worrying about how he would deploy his three divisions should the Germans attack the town. Reassuring the general as best he could, he left for the Gravina-Altamura-Gioia del Colle area where, he was told, he would find the elite German 1st Parachute Division.

During the night, they crossed the main supply route between Spinazzola and Gravina and almost blundered into a German convoy on the road. They drove on into the hill country of the Murge. Here the patrol split up to watch the roads and report all movements to 1st Airborne headquarters. While this was going on, Popski pulled off a coup.

He spoke adequate Italian, and in a friendly chat with an Italian farmer he learned that the farmer provided foodstuffs for the officers mess of the German garrison at Gravina. From a workable telephone at a railway station, he called the German quartermaster, a Major Schulz, and, posing as a loyal quartermaster of an Italian garrison that was being evacuated, asked the major if he would like to buy eight cases of good cognac for the mess. They haggled over the price and came to an agreement and, at Popski’s request, the major gave orders to the guards to admit two people in a captured American vehicle that night.

At 11 pm, in a jeep from which all military fittings had been removed, Popski and his driver, Jock Cameron, arrived at the major’s office carrying boxes of stones. Popski slugged the major with a cosh, and then they went through his papers. They found a copy of the complete strength, dated the previous day, of the 1st Parachute Division and all other troops in the area who were supplied by the Gravina distribution center. It included the locations of all units. He radioed the information to 1st Airborne.

The road watch figures and other intelligence PPA had supplied during the past few days made it clear the Germans did not have a large number of troops in the area. They deduced that when 1st Airborne, which was now being reinforced, advanced from the Taranto area, the Germans would fall back. This proved to be the case.

Holding the Ford Across the River Fortore

Considering his work with 1st Airborne now finished, Popski led his jeeps north behind the German lines looking for whatever damage he could do. During the next few weeks in the Foggia-Bovino area, PPA could do little more than keep a watch on roads, count traffic, try to identify the units the vehicles came from, and blow wheels off German trucks and tracks off armored vehicles with explosive gadgets invented and supplied by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). But their presence alone caused some confusion.

One day, while they were hiding in a grove of trees awaiting dark, two shabbily dressed men approached. They were obviously not Italian peasants, and when Popski stopped them he found they were Russian soldiers captured at Smolensk and sent to work in the Todt Organization, Germany’s labor establishment, in northern Italy. From there they had escaped and made their way south. Popski enrolled them in PPA, and they served with distinction for the rest of the war.

At the end of September, the remainder of PPA arrived with the buildup of Allied forces. Popski sent Captain Bob Yunnie with 10 men and four jeeps to reconnoiter the hills and valleys of the Gargano Peninsula, where it was thought there might be a large number of Germans. On the peninsula, Yunnie learned from villagers that the Germans had just left. He transmitted the information to the 4th Armored Brigade and pursued the Germans, across the mountains and down to the coast where, in late afternoon, they caught up with German sappers laying mines in a ford across the River Fortore. They attacked immediately, driving the sappers into the hills, then crossed the ford. But across the river they ran into heavy opposition and barely escaped destruction by mortars as they retired.

They spent the next three days keeping the ford open, chasing away any Germans who came close; nights were spent at the Castle Ripalta whose chatelaine was a lovely English girl married into the Parlato family. When British armor arrived in the area, they led the tanks and armored vehicles across the ford and into Serracapriola.

Halted by the German Line

Meanwhile, Popski and the rest of PPA were on reconnaissance 125 miles behind the front line in the Alban Hills southeast of Rome. They had traveled via Cassino and north along Route 6 to reach the hills but found no Germans there. They drove around the outskirts of Rome and then returned to base. Except for bringing back information on the whereabouts of the 16th Panzer Division and disabling a few of its vehicles, the reconnaissance had accomplished little.

By the end of November, the German line was stabilizing across the breadth of Italy, and Popski and Yunnie were unable to find gaps through which they could pass their jeeps. But they carried out some sorties and had a few brushes with German units. During one of these, near the town of Alberona, they found the South African General Hendrik Klopper wandering about; he had been captured at Tobruk and had recently escaped.

Back at base at Lucera and worried about the effect inactivity was having on his men and that there was no future for PPA, Popski went to see the chief of staff at Eighth Army headquarters. He was reassured about the future and told to rest his men farther back at Bisceglie while a new, more orthodox role and larger establishment was worked out for him.

The new establishment allowed for six officers (one major, two captains, and three lieutenants) and 74 other ranks, including wireless operators, armorers, and mechanics. Sufficient armed jeeps and trucks would be provided. With his expanded establishment, Popski planned three operational patrols of six jeeps, each patrol to comprise an officer, a sergeant, two corporals, a mechanic, wireless operator, and six driver-gunners. There would also be a small headquarters patrol, a workshop and wireless section, and an administrative section under Jean Caneri.

Popski went off recruiting, looking for men who were, or would soon be with training, expert in navigation; as drivers, machine gunners, mechanics; and in demolitions. Time was short for training, for Popski had been warned that PPA would take part in the landing at Anzio, so the newcomers were kept at it day and night in the snow-covered mountains. But at the last minute PPA’s participation in the Anzio landing was cancelled. It was a bitter blow.

Aborted Operation Astrolabe

Soon afterward, Popski was asked to send a patrol to destroy a bridge over the River Capa d’Acqua in front of a position held by a Guards brigade on the Garigliano Front. Popski sent part of Bob Yunnie’s patrol. Near the river the patrol ran into an uncharted minefield. One man was killed and two seriously wounded by the mines, and the patrol came under heavy German mortar fire in which another man was wounded. Yunnie managed to get the patrol out, but the bridge was not blown.

Popski moved his base to Besceglie at the foot of the Matese mountains and put the men to hard training while he worked on a plan to operate behind the German lines. The operation was to be named Astrolabe.

On June 12, Yunnie and a small advance party including two Royal Navy officers sailed in a Navy P-boat for the mouth of the River Tenna, 60 miles behind the front line. Here Yunnie met agents of “A” Force (M19), who were engaged in rescuing Allied airmen shot down in enemy territory; the agents brought the airmen to the coast and commandos took them out. Yunnie confirmed with the agents and the two Navy officers that an LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) would be able to get in with PPA’s jeeps, and he advised Popski of this by radio.

Three nights later, Popski arrived in an LCT with 30 members of PPA, 12 jeeps, and a detachment of 73 commandos of No. 9 Commando who would hold the beachhead while PPA landed and then return with the LCT.

The commandos immediately went ashore and took up positions to cover PPA’s landing. Popski went in with them and met Yunnie on the beach. Yunnie reported that, because his message confirming the landing point reconnaissance inland had shown heavy German traffic everywhere, the German Army was now in retreat. He said he did not think PPA had any chance of survival in the crowded enemy situation.

It was a blow for Popski. He did the only thing possible; he cancelled the operation. The commandos were called in, but when the LCT tried to move it was found she was fast aground. The Navy motor launch came to her assistance, but the LCT could not be moved. Then the motor launch, too, ran aground. Luckily the motor launch got off a sandbar, but there was no moving the LCT.

Popski ordered Yunnie and four of his men to stay ashore to report on the situation by radio, ordered all the rest onto the motor launch and the LCT, and then blew up the jeeps.

Joining With Italian Partisans

As soon as he was able to get replacement jeeps, Popski made his way to the mountain village of Sarnano, 40 miles southwest of Fermo, where Yunnie and his four men met him. They set off in 10 jeeps to the River Chienti, hoping to cross it and get behind the German lines.

When they started to ford the river, Corporal Cameron, Popski’s driver and friend, was killed, and Lieutenant Rickwood, in command of a patrol, was accidentally shot in the stomach after the action, by one of his own men carelessly cleaning his gun. Unable to cross the river because of the large number of Germans in the area, Popski pulled back to Sarnano, then crossed a 4,000-foot mountain range to the small town of Bolognola, where he came upon a band of 300 partisans. They were under the dual command of a Major Ferri and his brother Giuseppe, a history professor at the University of Pisa.

Though inexperienced, the partisans were achieving some success with captured German weapons and were delighted to combine with PPA, to exchange their knowledge of the country for PPA’s teaching in ambushing and other guerrilla tactics. For Popski, Bolognola was a good base. It overlooked the upper reaches of the River Chienti and beyond to the walled town of Camerino, which was the headquarters of a German mountain division.

The bridge across the Chienti had been destroyed, and German troops were in strength along the road on the other side. Most nights PPA and the partisans would drive down to the river and shoot up German convoys on the other bank. Soon the Germans pulled back from the river area. PPA crossed the river and drove on to the Potenza River, seven miles beyond Camerino, and blew the bridge over that river.

Strong, well-separated attacks and deception tactics convinced the German commander that large forces were operating all around him, and he withdrew his division across the Potenza. PPA and the partisans marched triumphantly into Camerino.

Popski was by now in command of both the partisans and PPA. He appointed Giuseppi Ferri, the university professor, to be civilian governor of Camerino and his brother, the major, commander of partisans, and stayed in Camerino for several days helping to set up a civilian administration until the arrival of the official Allied Military Government of Occupied Territory (AMGOT). He then led PPA north across the Potenza looking for more action.

For the next three months they raided German outposts, destroyed fuel and ammunition dumps, ambushed convoys, and liberated villages. With no more than 50 men at any time, they killed over 300 Germans with the loss of one man killed and three wounded and cleared 1,600 square miles of mountains.

Raiding With the Garibaldi Brigade

In the middle of September 1944, the Allies broke through the German Gothic Line stretching across Italy from Pesaro on the Adriatic to La Spezia on the Tyrrhenian Sea, but the German divisions commanded by Field Marshal Albert Kesselring retreated very slowly, fighting stubbornly for every river and canal crossing and defensive feature.

In the tangle of waterways along the coast of the Adriatic, Popski found that his jeeps were not able to operate effectively. Somewhere he heard that amphibious DUKW vehicles had arrived in the country, and he quickly acquired some and began training with them at Ancona. He allowed seven DUKWs to a patrol, six to carry armed jeeps and the seventh supplies and a chain-lift crane.

On November 1, he took his DUKWs across the River Savio and met a band of partisans of the Garibaldi Brigade led by Ateo Minghelli. The Garibaldi Brigade was communist, under the command of Arrigo Boldrini, but ready to cooperate with anyone fighting the Germans. Popski attached members of Minghelli’s band to each of his patrols.

The arrangement worked well. Throughout the bitter winter they harried the Germans from forest hideouts as part of the 27th Lancers’ “Porterforce” and pushed them back whenever the opportunity arose. The DUKWs enabled PPA to negotiate the many waterways of northern Italy, to outflank German positions and, on occasion, to be driven onto LCTs and driven off on beaches behind German positions.

The six armed jeeps of a patrol had tremendous firepower. Each jeep was armed with a .50-caliber and .30-caliber machine gun and each patrol carried two .303 Bren guns, a bazooka, and a 2-inch mortar. A smoke generator was fixed to the rear of each jeep. A broadside from six jeeps in line was devastating. Personal weapons included Thompson submachine guns, rifles, pistols, and grenades.

Although the risks were great, casualties were few. Replacements were quickly found. One replacement was a Lieutenant John Campbell, of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who took command of “S” patrol and distinguished himself in two daring and spectacular raids, earning himself two Military Crosses and promotion to captain.

The PPA’s Last Battle

In early December, PPA and its partisans were the first to enter Ravenna. Hearing that two troops of the 27th Lancers in a position along a road out of Ravenna were surrounded by Germans and needed help, Popski took a patrol to the scene. Under the covering fire of some tanks, he led his patrol to within 30 yards of two companies of Germans who were dug in on the bank of a canal from where they had the Lancers covered. The jeeps kept up a concentrated fire on the German position, allowing the Lancers to get away. Popski lost his left hand in the action. He was hospitalized, sent to England, and awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

In his absence, Jean Caneri took command of PPA and led it on operations until snow bogged down the jeeps. He then organized training for everyone in parachuting, skiing, and mountain climbing.

In April, Bob Yunnie obtained a compassionate home posting upon the death of his only son, and a recently recruited young lieutenant from the 27th Lancers named McCallum took his place as patrol leader. Patrol leaders were now McCallum, Captain John Campbell, and Lieutenant Steve Wallbridge.

On April 21, Caneri led all PPA, with his headquarters organized as a fighting patrol, into the watery maze around Lake Comacchio where, with the partisans of the Garibaldi Brigade and units of the 27th Lancers, they fought Germans for seven days. McCallum and his gunner were killed when a Panzerfaust anti-tank weapon destroyed their jeep as McCallum was leading his patrol into a village on the lake.

PPA crossed the rivers Po and Adige and ran into a large force of Germans at Chioggia. Using bluff, as Popski would have done, Caneri laughed off the fact that he had only nine men in three jeeps, saying there were large forces behind him, and persuaded the German commander that to continue fighting was hopeless. The commander surrendered his 700 men.

Two days later, Campbell’s patrol charged a battery of 88mm guns and captured it together with 300 troops. Two other patrols sailed across the Gulf of Venice and helped clear the Germans out of Iesolo. In 10 days, while killing and wounding many Germans, they had taken 1,335 prisoners and captured 16 field guns and many other weapons. It was a good haul, and it was PPA’s last battle.

Popski rejoined his army at Chioggia wearing a fearsome hook in place of his hand. On some shallow-draft Ramp Cargo Lighters (RCLs) manned by seven Royal Engineers known as “Popski’s Private Navy” he took his jeeps up the lagoon to Venice where, “for the sheer pleasure of it,” he led his jeeps around and around the Piazza San Marco. He then drove up into the Alps, heading for Austria. Near the border town of Tarvisio, he received a radio message telling him that Germany had surrendered. They drove into Austria.

Disbanded in Austria

In the 36 months of its existence, 20 of them spent on operations, PPA had been more of a brotherhood than a military unit, a brotherhood created and led by Popski. Though at its peak it numbered no more than about 120 men, its contribution to the war effort was impressive.

In Austria, PPA was disbanded and its members returned to their former units. Popski stayed in Austria, working as the liaison officer between the British and the Russians for that sector until 1946, when he was demobilized. He settled in England and married his second wife Pamela. Popski died in London in May 1951 of a brain tumor—famous from his writing, radio broadcasts, and best-selling book about PPA.

Postscript: On September 14, 2005, the 60th anniversary of the disbandment of PPA, Captain John Campbell CVO CBE MC and Bar led a commemorative visit of 30 PPA veterans, relatives, and friends, including both of Popski’s daughters, back to Italy to hold ceremonies of remembrance at PPA graves near Ravenna, with the group generously honored and hosted by the mayors of Ravenna and Venice and joined by many Italian Partisans.

On Sunday, March 30, 2008, Popski’s birthday, the PPA Memorial was unveiled by Sir Robert Crawford CBE, director-general of the British Imperial War Museum, assisted by Captain Campbell, and dedicated in the presence of nearly 250 PPA, LRDG, SAS, and Partisan veterans, relatives, and friends. It sits in the center of the Allied Special Forces Association’s Memorial Grove within the British National Memorial Arboretum (inspired by the USA’s Arlington Cemetery) in Staffordshire, in the very center of the United Kingdom.

My dad was Andy Walker gunner in the ops he is dead now at the age of 92 in Liverpool Uk,He told me lots of stories that aren’t in the book he was with Popskie when he had both his finger and hand taken off