By Blaine Taylor

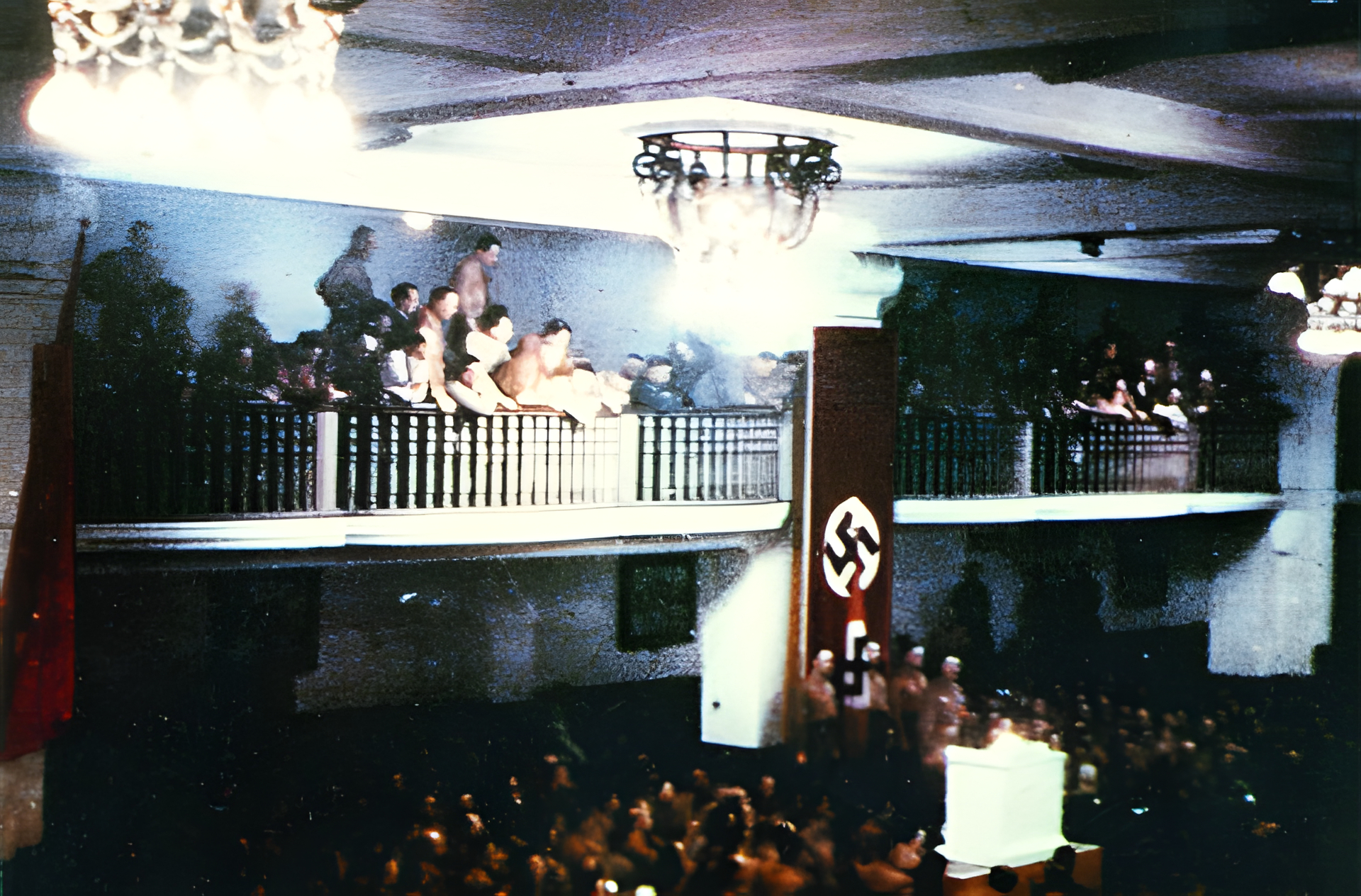

At exactly 8 PM on November 8, 1939, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler strode briskly into Munich’s Burgerbraukeller beer hall at the head of his glowering entourage, brushing past a forest of hands raised in the Nazi salute. As a band struck up the party anthem, the “Horst Wessel Song” (named after a dead SA storm trooper killed in a brawl with a Communist), Hitler and the other party leaders, including Josef Goebbels, Rudolf Hess, Martin Bormann, and Heinrich Himmler, took their seats at the plain wooden tables where so many Nazis had quaffed good Bavarian brews in years gone by.

The evening marked the 16th anniversary of Hitler’s abortive 1923 attempt to take over the German state by force. That would-be coup had ended in bloodshed and disaster, but since Hitler’s appointment as chancellor a decade later, the event had taken on a semireligious atmosphere in the Nazi pantheon of solemn holidays, commemorating those killed by police bullets when the future Nazi Führer was still an unknown street agitator. Now he commanded the mightiest nation in Europe.

Because of the just-begun war with Great Britain, France, and their allies, Hitler had not been expected to address the present gathering of Nazi “Old Fighters” and had in fact named Hess to be his stand-in. At the last minute, however, Hitler decided to come himself. At 8:10 pm, he took his place at the usual lectern, with a Nazi swastika flag covering the pillar directly behind him, six feet away. He immediately launched into a furious speech attacking the British, which had his supporters clapping and cheering. As he spoke, however, Hitler’s adjutant, Julius Schaub, passed him cue cards reminding him of the time—he had a train to catch. “Ten minutes. Five minutes. Stop!” read the cards.

Abruptly, Hitler ended his speech after 57 minutes, not the usual 90 minutes he devoted to listening to himself rant. He left his followers with the injunction: “Party members, comrades of our National Socialist movement, our German people, and above all our victorious Wehrmacht, Sieg Heil!” and stepped down from the podium. Normally, Hitler would have stayed behind to shake hands, but Schaub managed to hustle him out of the hall at 9:12 pm, closely followed by all the top members of the Nazi government. The group was in a limousine heading for the Munich train station when a muffled explosion was heard in the distance. What did it mean?

At exactly 9:20—a mere eight minutes after Hitler left the hall—waitress Maria Strobel was busy clearing Hitler’s table of empty steins and full ashtrays, fretting that the Führer had neglected to pay his bill. Suddenly, the ceiling exploded, and she was flung down the entire length of the hall and out through the doors. The smell of cordite lingered in the air, along with the thick choking dust of collapsed brick. Groans from the dying and wounded could be heard in the confusion. Among those emerging from the rubble covered with chalk dust was the father of Eva Braun, the Führer’s mistress. In all, seven people were killed and another 63 injured.

Climbing aboard his train, Hitler was blissfully unaware that he and his top men had narrowly avoided death. At Nuremberg, Goebbels, his face deathly pale, brought Hitler the news in the form of a telegram from Munich. Later, reflecting upon his miraculous luck, Hitler told photographer Heinrich Hoffmann: “I had a most extraordinary feeling, and I don’t myself know how or why, but I felt compelled to leave the cellar just as quickly as I could. The fact that I left the Burgerbraukeller earlier than usual is a corroboration of Providence’s intention to let me reach my goal.” Earlier that day, Hitler recalled, Gerdy Troost, the widow of his favorite architect, had warned him of a possible assassination, and he had been uneasy upon his arrival in Munich.

Immediately after the news, Himmler announced that the bombing had been “a foreign plot,” posted a reward for the culprits, and ordered the German frontiers sealed. In his diary, Goebbels claimed that the bombing had been the work of “Black Front” leader Otto Strasser, exiled in Paris since 1934, the year that Hitler had murdered Strasser’s older brother, Gregor, in the famed “Blood Purge” of June 30. Strasser denied any involvement in the attempt. Within the ranks of the secret anti-Hitler German Army resistance movement, there was talk that the number-two Nazi, Luftwaffe Field Marshal Hermann Göring, was behind it all and, indeed, Göring had been mysteriously absent from the annual ceremony. In truth, however, the portly Göring had not taken part in the attempt and had missed the occasion because of legitimate illness.

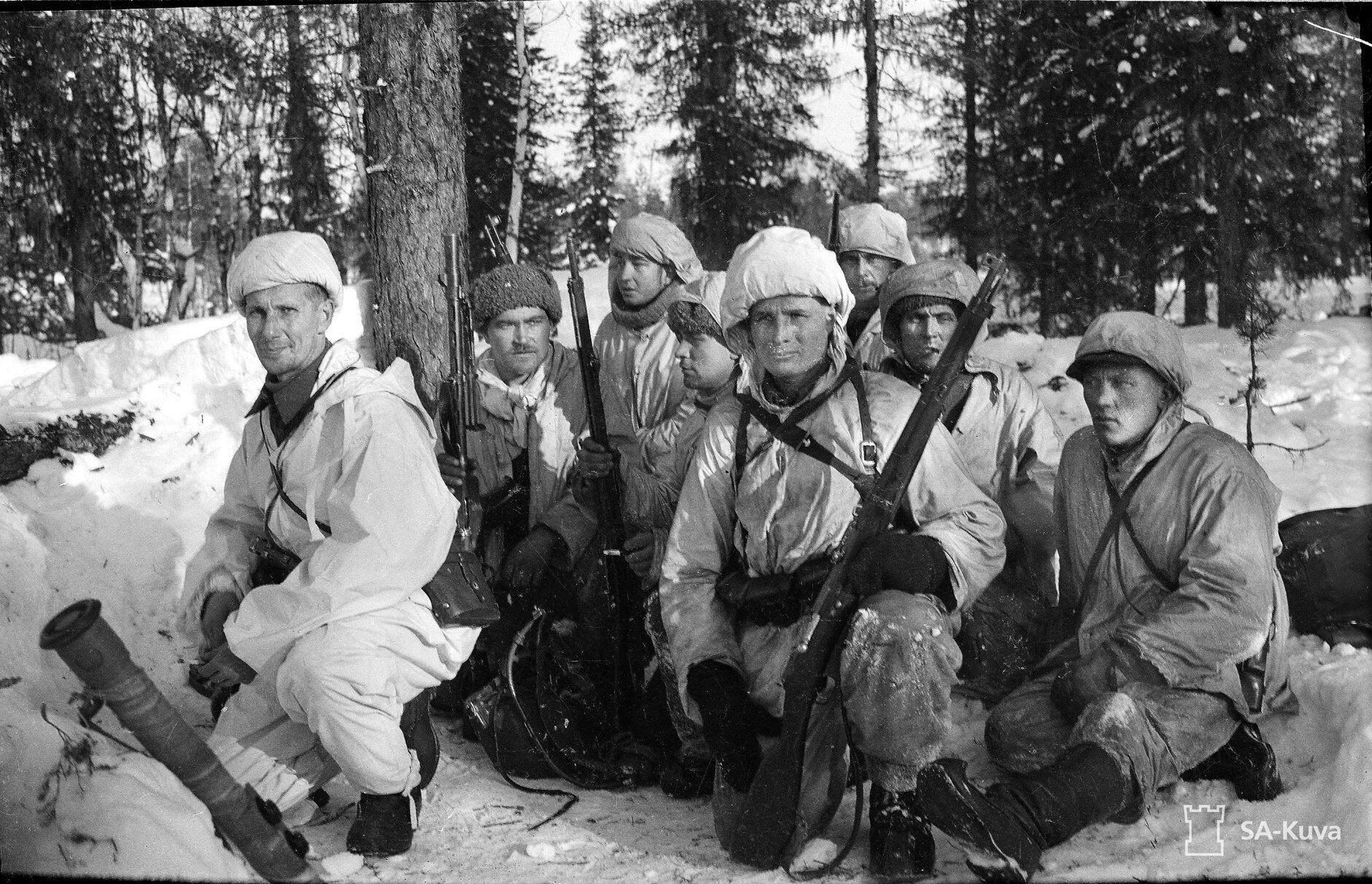

Who, then, was responsible? Within the resistance, there was consternation, as the monocled Prussian generals had been debating how best to depose Hitler and head off his planned assault on the West ever since the victorious conquest of Poland a few weeks earlier. Indeed, on November 5, Hitler had had a furious argument with General Walther von Brauchitsch at the Chancellery, during which time the general had claimed that there was talk of mutiny in certain German Army units, reminiscent of 1918, and a refusal to fight the British and French. Enraged, Hitler shouted: “What action has been taken by the Army commander? How many death sentences have been carried out?” He stormed out, slamming the door behind him.

Himmler had long suspected that there was a putsch in the offing, an event feared by the Nazis since they had taken office in 1933. He and the head of the Nazi Party secret police, SS General Reinhard Heydrich, had instructed Colonel Walter Schellenberg to open contacts with the British Secret Service in Holland. The trim, dapper Schellenberg passed himself off to the unsuspecting British as a representative of the German underground movement. At 2 am on November 9, Schellenberg was awakened by a telephone call from Himmler, who told him of the attempt on the Führer’s life. Hitler, he said, believed that it was a British plot, and over Schellenberg’s strong objections to the contrary Himmler ordered him to abduct the two British agents later that same day.

At 3 pm, a black Buick drove up to Venlo, on the Dutch side of the frontier; inside were British Major S. Payne Stevens and Captain R.H. Best, along with a Dutch officer. Suddenly, a car carrying several pistol-brandishing SS men roared across the border, and a five-minute gunfight ensued in which the Dutch officer was mortally wounded and Schellenberg himself missed by inches being struck by an SS bullet. Stevens and Best were hustled into Germany. Hitler wanted to place them on trial, but the evidence simply wasn’t there to incriminate the pair. In a rage, the Führer blamed the lax security measures of the SS at the Burgerbraukeller.

Another viewpoint was expressed by Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, Benito Mussolini’s son-in-law, in his secret diary entry of November 8, 1939. “The attempt on Hitler’s life at Munich leaves everybody quite skeptical, and Mussolini is more skeptical than anyone else,” he wrote. “In reality, many of the aspects of the affair do not altogether convince us of the accuracy of the account given in the papers. Either it is a master plot on the part of the police—with the overdone purpose of creating anti-British sentiment in the German people who are quite indifferent—or, if the murder attempt is real, it is a family brawl of people belonging to the inner circle of the Nazi Party; perhaps a carry-over of what took place on the 30th of June [1934] which cannot have been forgotten in Munich.”

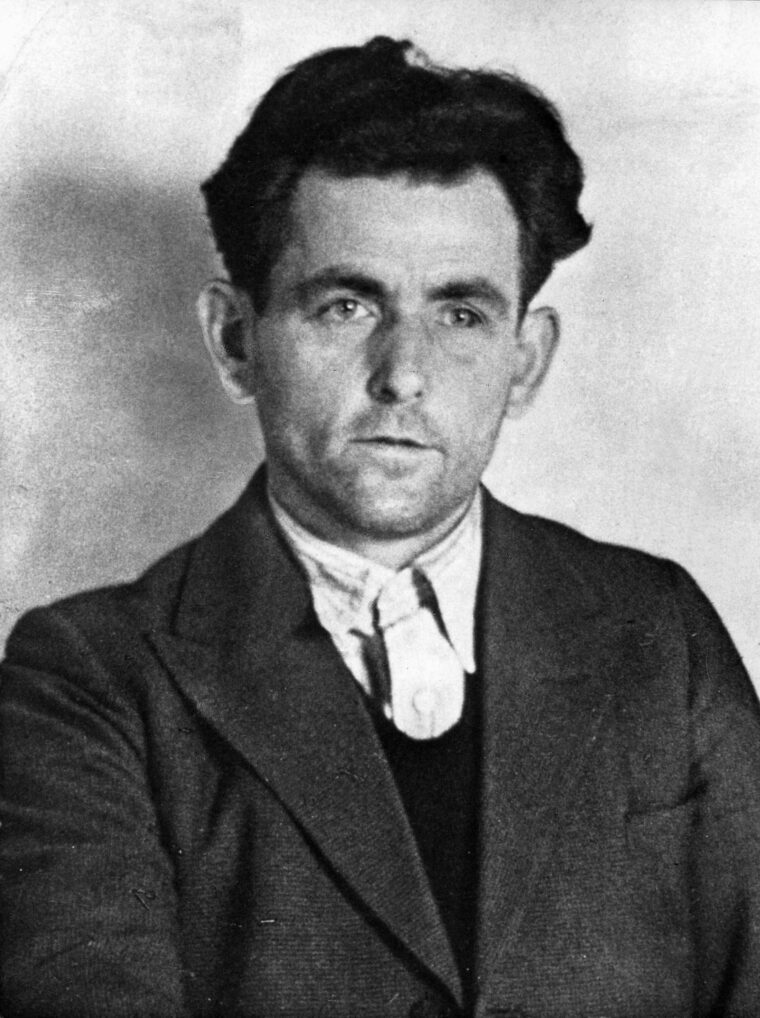

The real culprit was much more prosaic. Rather than being an aristocratic, high-ranking German officer or a pair of suave British spies, he was an unassuming 36-year-old Swabian cabinetmaker, Johann Georg Elser, whose only previous political activity was to become a member of the local woodworkers’ union. Elser was angry at Hitler for failing to cure unemployment and for leading Germany into a war that Elser felt was a lost cause from the start. Noting that Hitler was always surrounded by heavily armed guards and rarely appeared or traveled at set times, Elser decided to strike at the one moment and place where the Führer almost never failed to appear—the Burgerbraukeller in Munich on November 8.

On that day a year earlier, Elser had stalked Hitler at the same beer hall, watching him and other Nazi leaders stride down the boulevard in their annual commemorative march for the dead of 1923. Ironically, at that same moment another would-be assassin, Swiss waiter and ex-seminarian Maurice Bavaud, was in the same crowd, trying unsuccessfully to use a pistol to shoot Hitler from a distance. Bavaud was caught and later beheaded for his troubles.

Elser was more careful and diligent. He worked in a mine quarry and had access to explosives. Beginning in August 1939, Elser smuggled himself into the Burgerbraukeller every night for 35 days, working on the pillar undetected and silently in the dark with a flashlight, installing his time bomb, complete with a hidden compartment and a hinged door. On November 6, 63 hours and 20 minutes before the actual explosion, Elser set the timing device on the mechanism and left. He returned to check it on the 7th at 9 pm, and then headed for the Swiss frontier, where he was arrested at Constance, Germany, on suspicion of smuggling just before the actual Munich detonation. A search of his knapsack revealed pliers, suspicious metal parts, handwritten notes on explosives making, and a postcard of the Burgerbraukeller.

Brought to Berlin, Elser was brutally interrogated, kicked in the ribs several times by Himmler himself. Bloodied, Elser denied all knowledge of a wider plot, although he reportedly admitted that two mysterious men had supplied him with the explosives. He did not know who they were, Elser claimed. That same day, November 9, Hitler decided not to march in the Beer Hall Putsch commemoration as in years past. On the 10th, still fearful of army reaction to his western assault plans, he postponed the jump-off date of November 15 for the first of 29 times. (It finally took place on May 10, 1940.) On November 11, Hitler attended the public funeral in Munich for victims of the blast.

Meanwhile, Elser was sent to Dachau concentration camp, where he later smuggled a note to Best and Stevens claiming that he had been brought before the commandant at Dachau in October 1939 and given the bomb by the two unknown men—SS agents?—who had persuaded him to plant the device to kill “traitors against the Führer.” According to Elser’s alleged account, the explosion was intentionally delayed until after Hitler left the building.

Was any of this true? Was Schellenberg, in fact, a double agent for the British? He survived the war, escaped being tried as a war criminal at Nuremberg, and died peacefully in 1948 of natural causes. Was the explosion caused by a dissident Nazi anti-Hitler movement angry over the Nazi-Soviet Pact of the previous August? Was the blast calculated by Hitler himself to whip up German enthusiasm for the war, as American radio correspondent William Shirer believed? Or was there actually an SS plot to take over the Third Reich in 1939? We will never know for sure. Heydrich was assassinated in 1942, and Himmler died a suicide in 1945, taking his secrets with him to the grave. He had, however, seen to it that Georg Elser lived an almost privileged existence at Dachau, and even provided him with tools and wood to make cabinets.

Whatever the case, on April 5, 1945, with Allied troops drawing ever closer, Himmler ordered his henchmen at Dachau: “During the next air raid, see to it that Elser is mortally wounded. Destroy this order when the deed has been executed.” Four days later, as American bombers flew overhead, the little cabinetmaker was led from his cell at Dachau and shot, the last victim of the audacious bombing that very nearly had saved the world from the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust.

In 2003, the German government honored Georg Elser with a postage stamp bearing his stated reasons for the bombing: “I wanted to prevent the war.” It was a fitting if simple epitaph for a still largely unknown hero.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments