By Mike Haskew

As the last days of 1943 slipped away, World War II in Italy ground to a miserable stalemate. Below the eminence of Monte Sammucro, the town of San Pietro lay in ruins, its destruction so thorough that surviving civilians rebuilt their homes some distance away, leaving the heaps of rubble as mute testimony to the ravages of war. “For 17 days, we had existed on the peak,” wrote one disheartened American soldier, “in freezing weather, constant rain, icy winds and inconceivable danger. In all that time we had never washed our hands or shaved, and had managed to get our boots off three times. Lice were eating the hide off our bodies and desperation was eating out our hearts.”

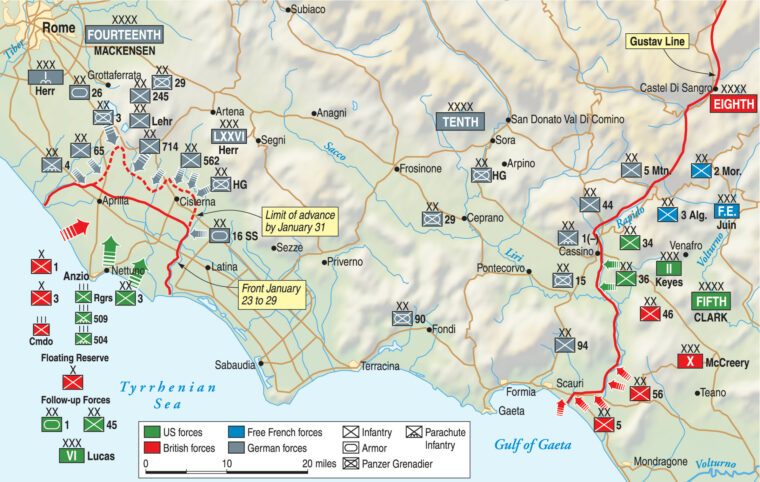

The desperation among the ranks was also being felt on a strategic scale as the agonizing Allied advance toward Rome proceeded at a snail’s pace. The majority of Allied resources had been earmarked for England and eventually the Normandy invasion, while the Italian campaign was rapidly becoming a backwater. By mid-December, the offensive of General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army had bogged down. The 36th Division had lost 150 dead, 800 wounded, and 250 missing during the fight for San Pietro, which commanded the approach to Rome along Highway 6. To the east, the British Eighth Army, under General Sir Bernard Montgomery, remained stalled before the Nazis’ Gustav Line defenses north of the Sangro River around Ortona.

Kesselring’s Winter Line

Taking full advantage of the rugged Italian terrain, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commanding German forces in the Mediterranean, had personally overseen the construction of three fortified defensive lines, which collectively came to be known as the Winter Line. The first two lines, named Barbara and Bernhard, were considered formidable enough for delaying actions only. But Kesselring, having convinced Adolf Hitler that a firm stand south of the Eternal City was preferable to a general withdrawal to the Alps and abandoning Rome to the Allies, intended to hold tight at the Gustav Line, 12 miles north of the Bernhard Line. General Hans Bessel, an engineer with great talent, had overseen the construction of bunkers, machine gun and artillery emplacements, and the location of minefields along the Gustav Line. A number of ingeniously devised mobile strongpoints, which could be occupied quickly to take on the advancing enemy and then towed to other danger points, had also been built.

Significant changes in the Allied command structure in the Mediterranean had taken place as 1943 waned. On November 18, General Geoffrey Keyes and the headquarters of the U.S. II Corps arrived from Tunisia. Keyes had taken tactical command of the 36th and 3rd Divisions, the former replacing the latter in the line. On January 8, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower formally assumed his duties as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, and departed for England to direct Operation Overlord. General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, a Briton, was elevated to Eisenhower’s former post as Mediterranean Theater commander, while General Jacob L. Devers, an American, was to serve as his deputy. Montgomery also left the Mediterranean, taking command of the 21st Army Group in England, and was succeeded by General Sir Oliver Leese as commander of Eighth Army. British General Sir Harold R.L.G. Alexander remained in command of the Allied 15th Army Group in Italy, while Clark would continue to lead the Fifth Army.

Discussions concerning an amphibious landing to outflank the German Winter Line defenses had been ongoing, and as early as November, Eisenhower had considered sending troops ashore at the resort city of Anzio, 35 miles south of Rome. English Prime Minister Winston Churchill was in favor of such an undertaking, and its prospects for success were addressed during the high-level conferences at Cairo and Tehran. Eisenhower harbored lingering misgivings about the endeavor, however, and did not actively pursue its planning. “There was a lack of decisiveness in the preparatory work for the Anzio attack,” Eisenhower wrote, “an attack which was to be executed after my own connection with the Mediterranean should be terminated. I learned that the individuals who would bear final responsibility felt some hesitancy in making decisions because my assignment had not yet been officially concluded. Therefore I instantly abandoned the plan for returning to Africa and recommended to General [George] Marshall that prompt action be taken to terminate my connection with the theater and to place all authority in the Mediterranean in the hands of General Wilson.”

“Becoming Scandalous”

The British accession to command in the Mediterranean and the continued grinding pace of offensive action against the Winter Line revived the planning for the Anzio landing, code-named Operation Shingle. Subsequently, it was scheduled for January 1944. Although it had once appeared that an amphibious operation to outflank the Gustav Line and drive for Rome had been canceled for good, the stillborn Operation Shingle was rapidly revived as a result of the restructuring of command in the Mediterranean with a distinctive British perspective. Well aware that the window of opportunity for a notable success in Italy was rapidly closing, Churchill departed the conferences at Cairo and Tehran decidedly pessimistic about the prosecution of the war on his favorite front.

Physically exhausted, the prime minister was diagnosed with pneumonia on December 11 while in Tunis to visit with Eisenhower. During a week in bed, Churchill worried that something must be done to energize the Mediterranean campaign. The solution, he reasoned, was the long-delayed amphibious operation. His sights set squarely on the capture of Rome, Churchill cabled his chiefs of staff on December 19 that “the stagnation of the whole campaign on the Italian Front is becoming scandalous.”

The availability of landing craft was essential for the execution of an amphibious operation, and twice the deadline for the removal of these scarce vessels to England had been postponed. After lengthy discussions with senior commanders, Churchill sent a telegram to President Franklin D. Roosevelt requesting that the craft be made available in the Mediterranean until February 5. Without them, he warned, “the Italian battle will stagnate and fester on for another three months. If this opportunity is not grasped, we must expect the ruin of the Mediterranean campaign of 1944.”

Roosevelt agreed to allow 56 transports to remain, partly due to the fact that Churchill admitted he had already set the plan for Anzio in motion. On Christmas Day, shortly after Churchill’s conference with his generals concluded, Alexander contacted Clark and informed him that Operation Shingle was to proceed. Roosevelt’s decision had been qualified with an insistence that other landing craft due to arrive in the Mediterranean via the Indian Ocean would instead be diverted directly to England and that a number of others should be released as scheduled. Churchill had agreed at Cairo and Tehran that nothing should be done to interfere with the timetable for the Normandy invasion and a complementary landing in southern France, and Roosevelt tersely reminded him of that agreement.

Clark reconsidered his opposition to Anzio and gave his support, while he also assumed command of Seventh Army from General George S. Patton, Jr., who was transferred to England. Clark was also responsible for the planning of the invasion of southern France, which was initially called Operation Anvil (later Operation Dragoon). The demands of planning two amphibious operations in the Mediterranean threatened once again to cause the cancellation of one or the other. However, Clark voiced no strong opposition and was willing to move ahead with both.

Planning Operation Shingle

The risks of Operation Shingle were obvious. A force of approximately two divisions was to be landed at Anzio, 35 miles south of Rome. The last natural defensive barrier before Rome, the Alban Hills, was 20 miles inland. The hills would have to be seized either by the Anzio landing force or by the Fifth Army, which would be required to breach the Gustav Line at Cassino and drive northward to link up with the force at Anzio. Compounding the concern was the fact that the advance positions of the Fifth Army were 70 miles from the beaches at Anzio. Furthermore, each offensive thrust was dependent, it seemed, on the success of the other. Failure of one was likely to result in the failure of both.

VI Corps headquarters, under General John P. Lucas, was to command Operation Shingle. The landing, scheduled for January 22, was to be undertaken by the U.S. 3rd Division, the British 1st Division, and detachments of U.S. Army Rangers, elements of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and British commandos. Altogether, the assault force would total 40,000 men. Some planners expressed concern that the force was too small to succeed in its assigned task. Clark wrote in his diary, “We are supposed to go up there, dump two divisions ashore with what corps troops we can get in, and wait for the rest of the Army to join up. I am trying to find ways to do it, not ways in which we can not do it. I am convinced that we are going to do it, and that it is going to be a success.”

The lure of Rome during the winter of 1943-1944 was intoxicating to Allied leaders, particularly Churchill and Clark. The liberation of the Eternal City might well strike a blow to Axis morale and provide a boost for the war-weary people on the home front. But at what cost? Although the Fifth Army had not reached Frosinone in the Liri Valley, the plan was ordered to proceed. Both the Rapido and the Garigliano Rivers would have to be crossed while soldiers on the heights of Monte Cassino and Sant’Ambrogio, which overlook the Liri Valley, would threaten any troops below. Still, Clark believed that his river crossings would force the Germans to send troops to the south and, at the very least, give the troops at Anzio an easier time.

When Lucas was informed that the Anzio operation was to proceed, he had immediate misgivings. “I felt like a lamb being led to the slaughter,” he confided in the pages of his diary. “This whole affair has a strong odor of Gallipoli.” He was referencing the disastrous World War I employment of Commonwealth forces against Ottoman Turkey in 1915, an operation ostensibly undertaken to relieve pressure on the faltering armed forces of czarist Russia. During months of protracted fighting along the coast of the Dardanelles, Allied troops had been cut to pieces before eventually being withdrawn. The champion of the Gallipoli offensive was none other than Winston Churchill, who at that time held the office of First Lord of the Admiralty. The debacle in the Dardanelles cost Churchill his job and eventually led to his ouster from the British government. He then spent the succeeding three decades painstakingly rehabilitating his political career with the baggage of Gallipoli ever present.

Eight days before Operation Shingle commenced, Lucas remained less than optimistic. On January 14, he wrote that the “Army has gone nuts again. The general idea seems to be that the Germans are licked and are fleeing in disorder and nothing remains but to mop up. The Hun has pulled back a bit but I haven’t seen the desperate fighting I have during the last four months without learning something. We are not (repeat not) in Rome yet. They will end up putting me ashore with inadequate forces and get me in a serious jam. Then, who will take the blame?”

Crossing the Garigliano

The Fifth Army’s December effort to force the gateway to the Liri Valley and capture Frosinone continued in January. Clark devised a plan to accomplish his dual purposes of gaining ground and drawing forces south from the Anzio area. During the first three weeks of 1944, the British X Corps was ordered to capture Cedro Hill, which stood 500 feet high, cross the Garigliano, and secure a bridgehead at Sant’Ambrogio. General Alphonse Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps replaced Lucas’s VI Corps and was to attack the Cassino area from across the mountains. Success in these efforts would secure the north and south shoulders above the Liri Valley.

II Corps was to capture the towns of Cervaro and San Vittore, as well as the high ground at Monte Trocchio, Monte Porchia, Monte Majo, and La Chiaia. When these objectives had been reached, the 36th Infantry would cross the Rapido, allowing the 1st Armored Division to pass through and speed along the valley floor to Frosinone. It was hoped that the Fifth Army would achieve success rapidly enough to link up with VI Corps at Anzio.

When the British 5th and 56th Divisions launched an assault by boat and amphibious landing craft across the Garigliano on January 17, they were confronted only by the inexperienced German 94th Division, which was thinly stretched from the river to the town of Terracina, 30 miles to the north. German planners had hoped that the natural barrier of the river itself and 24,000 thickly sown mines might provide enough assistance to repulse a crossing. At 9 pm, the attack got under way, and combat engineers worked to clear the mines and mark exits on the far bank while German artillery came down steadily. It was virtually impossible to construct bridges during the first 24 hours. Nevertheless, 10 full battalions of infantry crossed the Garigliano and moved inland.

“The Greatest Crisis Yet Encountered”

General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, commanding the XIV Panzer Corps, began to realize the gravity of the situation. Bypassing Col. Gen. Heinrich von Vietinghoff gennant Scheel, Kesselring’s deputy theater commander, Senger telephoned Kesselring, who immediately realized that a British breakthrough to the Liri Valley would outflank the defenses of Monte Cassino, unhinge the Gustav Line, and force a retreat of the entire XIV Panzer Corps toward Rome. Kesselring called Vietinghoff and barked, “I am convinced that we are now facing the greatest crisis yet encountered.”At the risk of weakening the defenses of Rome unnecessarily, the field marshal transferred the 90th and 29th Panzergrenadier Divisions along with the I Parachute Corps to the threatened Garigliano area the next day. He acknowledged that the German 10th Army was “hanging by a slender thread.”

As German reinforcements began to stream toward the threatened Garigliano area, the 5th Division had penetrated three miles beyond the river and captured the town of Minturno, while the 56th Division had consolidated a two-mile bridgehead and advanced into the nearby hills. The initial promise, however, was soon tempered by a notable failure. On the night of January 19, the 46th Division attempted to seize the Sant’Ambrogio heights, but fierce German resistance and the swift current at the confluence of the Liri and Gari Rivers doomed the assault. Cables intended to hold rafts and ferries were swept away, and only a few British soldiers managed to reach the far side of the Garigliano. They were withdrawn the next morning.

Clark described the failure as “quite a blow,” but deemed it necessary for the 36th Division crossing of the Rapido set for January 20 to go ahead as scheduled to assure that German troops were pinned down and could not disrupt the landings at Anzio two days later. The Rapido crossing, perilous due to the nature of the terrain and the certainty of heavy German resistance, was further endangered by the fact that neither of its flanks was secure. Although he had succeeded in drawing enemy troops away from Rome and Anzio, Clark was unable to fully grasp the situation. The result was tragic.

In hindsight, the disastrous attempt of the 141st and 143rd Infantry Regiments of the 36th Division to cross the Rapido appears doomed from the start. The attack began in darkness, with heavily laden troops obliged to carry unwieldy wooden boats weighing 400 pounds to the water’s edge. Accurate German artillery fire took a tremendous toll, and efforts to bridge the swift current were inadequate. By daylight on January 21, only about 1,000 men of the 141st had reached the far side of the Rapido. These were soon ordered to retire. The 1st Battalion of the 143rd took nine hours to complete its crossing. By 6 pm, it was all over. A handful of those who had crossed the river managed to escape. The operation cost the 36th Division more than 2,000 casualties, with at least 450 dead. Survivors blamed Clark and labeled him incompetent. Ultimately, a congressional investigation cleared him of any charges.

A Smooth Landing at Anzio

On the heels of the Rapido debacle came the landing at Anzio. Operation Shingle was set in motion on January 21. Three days earlier, a rehearsal had gone badly awry, with the embarrassing result that more than 40 amphibious vessels had been lost along with 28 valuable artillery pieces and antitank weapons. It was a foreshadowing of the frustration to come. In his orders to Lucas, Clark had been deliberately vague, instructing the VI Corps commander to seize and secure a beachhead in the vicinity of Anzio and advance on the Alban Hills. On January 12, General Donald Brann, a Fifth Army staff officer, visited Lucas. Brann made it clear that Lucas’s primary mission was to seize and secure a beachhead. This was the extent of Clark’s expectations. Clark did not want to force Lucas into a risky advance that might lose the corps. If conditions at Anzio warranted a move to the hills, Lucas was free to do so, but Clark and the Fifth Army staff believed this to be a slim possibility.

Apparently, Churchill and Alexander believed that Operation Shingle was to be a major offensive in itself, while Clark and Lucas considered it a diversionary tactic that would cause the Germans to eventually weaken their defenses at the Gustav Line, where the Fifth Army would make the main effort to capture Rome. Regardless of the confusion, when American and British troops splashed ashore at Anzio behind a heavy naval bombardment, they achieved notable success almost immediately. Three battalions of Rangers captured the port city with hardly a shot fired, and paratroopers moved into the town of Nettuno, two miles down the coast. By the end of the first day, Allied troops had penetrated up to three miles. Lucas bragged: “We achieved what is certainly one of the most complete surprises in history. The Biscayne [his headquarters ship] was anchored three and a half miles off shore, and I could not believe my eyes when I stood on the bridge and saw no machine gun or other fire on the beach.”

Lost Time and Hesitation

Kesselring had been caught with his pants down. His reserves had been committed to the Garigliano, and there were practically no troops left to oppose a VI Corps advance to the Alban Hills and the gates of Rome. In the face of impending disaster, however, Kesselring did not lose his nerve. Urgently, the field marshal requested that Hitler authorize the transfer of troops from the Balkans and northern Italy to Rome. The 4th Parachute and Hermann Göring Divisions were ordered to contest any advance from Anzio toward the Alban Hills, while the 715th and 114th Divisions were coming from southern France and Yugoslavia, and the 92nd Division was activated. In addition, the Fourteenth Army in northern Italy was instructed to send elements of the 65th, 362nd, and the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Divisions to Anzio. Vietinghoff also sent the headquarters of the I Parachute Corps and elements of the 3rd Panzergrenadier, Hermann Göring, 26th Panzer, and 1st Parachute Divisions northward.

During an exhausting day, Kesselring believed he had accomplished a great deal, staving off a potential disaster and even concluding that he might contain the Anzio beachhead. Kesselring turned down a request from Vietinghoff to abandon the Gustav Line defenses since he believed that his depleted forces would have great difficulty maintaining their positions. The crisis had by no means passed entirely, and a purposeful advance by VI Corps could still have made huge gains. General Siegfried Westphal, Kesselring’s chief of staff, wrote later, “On January 22 and even the following day, an audacious and enterprising formation of enemy troops could have penetrated into the city of Rome itself without having to overcome any serious opposition. But the landed enemy forces lost time and hesitated.”

During the early phase of Operation Shingle, Lucas concentrated on accumulating supplies and consolidating his beachhead, which expanded to more than 10 miles. While nothing in the way of a major offensive was undertaken, it was still necessary to secure the hills just beyond Anzio. Kesselring, meanwhile, observed his forces growing in strength. Within three days, he had transferred the Fourteenth Army headquarters from Verona to take command of eight divisions assembled at Anzio, while elements of another five were en route. For Vietinghoff to regain his diverted strength, it became of paramount importance for the new commander in the area, General Eberhard von Mackensen, to launch a counterattack and eliminate the beachhead as soon as possible.

The Allies Wait Below the Alban Hills

On the Fifth Army front, Clark renewed his effort to move into the Liri Valley after he received word that the VI Corps was firmly established at Anzio. Following the stinging reversal at the Rapido, Clark looked to the flanks of the valley entrance and decided to move the 34th Division across the Rapido north of Cassino and over the jagged peaks of the Cassino Massif. With this accomplished, Allied troops would, at long last, be in the Liri Valley nearly four miles north of Monte Cassino and the Rapido.

After nearly a month of fighting, the Allied forces achieved limited gains but were unable to continue their advance. During the January battles, Keyes’s II Corps sustained 12,000 casualties, while at the Garigliano bridgehead to the south, McCreery’s X Corps took more than 1,000 prisoners but lost 4,152 killed, wounded, and captured in an unsuccessful two-week effort to secure an avenue into the Liri Valley from the south. Some of the support companies of the 34th and 36th Divisions—cooks, clerks, and truck drivers—had been given weapons and formed into provisional combat units.

The urgency of the situation was apparent to everyone in senior command. Although the landing at Anzio had been intended to facilitate a breakthrough and rapid movement toward Rome from the Cassino area, the Anzio beachhead itself had become imperiled. The troops fighting at Cassino could not afford to rest for long and allow the Germans to strike a decisive blow to VI Corps, a few miles to the north.

When VI Corps landed against little opposition at Anzio, Lucas faced a momentous decision. Swift movement might secure the Alban Hills and the road to Rome and bring to an end the bloody stalemate to the south. Failure in such a movement might mean the loss of the entire corps. Playing it safe might ensure that the beachhead threatened the Germans continually, and that option seemed infinitely more palatable. The ambiguity of Clark’s orders was still on the commander’s mind as he weighed his choices, but the clock was ticking. Lucas fatefully decided to wait nine days before launching any significant offensive against the Alban Hills, although possession of the hills was a key to sustaining the beachhead even in a defensive posture since the Germans who occupied these heights had full view of every major movement within the Allied perimeter.

As it was, whatever opportunity may have been available was quickly extinguished by the swiftness of the German reaction to the Anzio threat. During the first three days of Operation Shingle, elements of the U.S. 3rd Division had moved to within four miles of the town of Cisterna to the northeast, while the British 1st Division captured the town of Aprilia and its cluster of abandoned collective farm buildings, which the troops had nicknamed “the Factory.” Lucas believed that his consolidated beachhead was something of an accomplishment. Still, he did not rush to the Alban Hills, nor did he urge the 1st Division on toward the towns of Campoleone or Albano, which stood at the junction of the Albano-Anzio road and Highway 7, the nearest main artery into Rome. He wrote in his diary, “I must keep my feet on the ground and my forces in hand and do nothing foolish.”

A Sluggish, Costly Advance

On January 30, Lucas finally set a coordinated offensive in motion. The British 1st Division, supported by tanks of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, quickly captured Campoleone. The armor, however, could not traverse the waterlogged ground efficiently, and the British gain was tempered by a frustrating inability to exploit it. At the same time, the 3rd Division, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and three Ranger battalions under Colonel William O. Darby were to take Cisterna and cut Highway 7. Truscott, commanding the 3rd Division, placed the Rangers at the point of his thrust, and all seemed to go well in the beginning. The Rangers crossed an arm of the Mussolini Canal at 1:30 am, and crept along, apparently undetected, in a nearly dry irrigation ditch. As daylight approached, the Rangers had reached the outskirts of Cisterna.

When they emerged from the confines of the ditch, disaster struck. Veteran German troops of the Hermann Göring and 715th Divisions were waiting, supported by armor and well entrenched in advantageous positions. A total of 767 Rangers had set out for Cisterna. Only six returned. One battalion of the 3rd Division fought for 30 hours, reached Cisterna, and nearly cut Highway 7, but it suffered 650 casualties from an original strength of 800 in the process.

The buildup of German forces at Anzio had reached nearly 100,000 men at the beginning of February, and Mackensen initiated a week-long effort to position his forces for an offensive to eradicate the beachhead. Attacking the British at Campoleone, the Germans compelled Lucas to order a withdrawal, which was executed brilliantly although the 1st Division sustained 1,500 casualties in the process. The attackers retook Aprilia and “the Factory.” Hitler railed that the “abscess” of the Anzio beachhead had to be eliminated, while Churchill was also distressed by the lack of Allied progress. “I had hoped that we were hurling a wildcat onto the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale,” he groused. Mackensen’s preliminary objectives had been achieved, but his forces had taken substantial casualties and would require reinforcements before a decisive push.

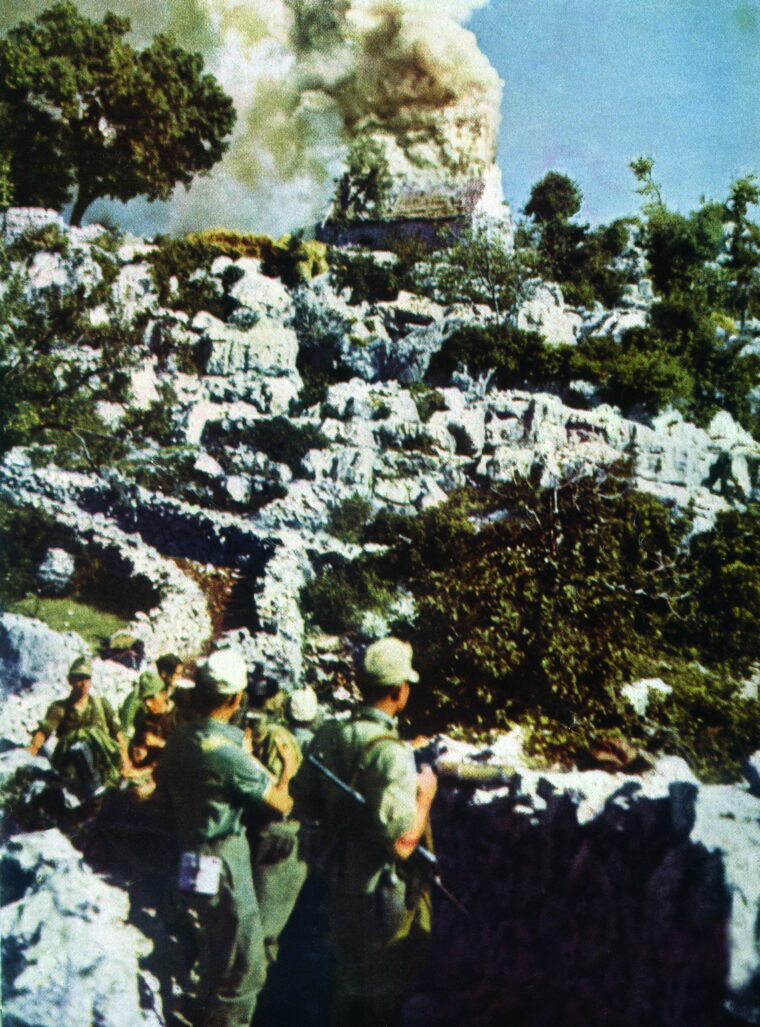

At Cassino, the Fifth Army was proceeding with plans for another attempt to breach the Liri Valley defenses. This time, the New Zealand Corps, as the 2nd New Zealand and 4th Indian Divisions were collectively designated, would lead the effort. The New Zealand Corps commander, General Sir Bernard Freyberg, a combat veteran of World War I, intended to send the 4th Indian against forbidding Monte Cassino, crowned by its ancient Benedictine abbey, while the New Zealanders were to capture the town of Cassino. As a prelude to the movement of his troops, Freyberg considered it essential that the abbey be reduced by aerial bombardment. Freyberg’s plan precipitated one of the most controversial decisions of World War II. Beginning at 9:45 am on February 15, Allied planes began dropping a total of 600 tons of bombs on the abbey, inflicting some 300 civilian casualties. Elite German airborne troops took up strong defensive positions in the rubble and fought stubbornly for days before evacuating.

The American Line Inches Back

While the drama at Monte Cassino unfolded, the Allied troops at Anzio were, as Lucas had predicted, fighting for their very lives. Both Allied forces, at Anzio and Cassino, had bogged down, and neither could offer much in the way of support for the other. Mackensen had gained favorable ground early in February to launch his major attack against the Anzio beachhead. On the 16th, he unleashed a powerful blow along the Albano-Anzio road, hitting the three regiments of the 45th Division, which had come ashore a few days earlier. The primary German thrust was to be carried out by the 3rd Panzergrenadier, the 114th, and the 715th Divisions along with the Infantry Lehr Regiment, a demonstration unit which had been used for instructional purposes in Germany but had never seen combat. A diversionary attack against the 3rd Division was stopped cold, but a second against the 56th Division penetrated the defensive line two miles before British reserves plugged the hole.

German artillery fire erupted all along the 45th Division’s six-mile front. Those who dared to lift their heads above the rims of their foxholes were greeted by an astonishing sight: scores of Mark IV and Mark VI panzers, accompanied by thousands of men from the 3rd Panzer Grenadier and 715th Infantry Divisions, rushing at them in their ankle-length overcoats, spilling across Anzio’s soggy, cratered landscape. Concentrated fire from more than 200 American and British artillery pieces joined the 45th Division infantrymen in the stand against the onrushing enemy. The German tanks were hampered, just as their Allied counterparts had been, by the seeming endless quagmire of mud. Still, the Germans pressed their attack. Some positions of the 157th Infantry were overrun, and the three regiments of German tanks and panzergrenadiers bowled into several companies of the 3rd Battalion, 179th Infantry. Casualties were staggering. Rifles, pistols, and automatic weapons added a staccato punctuation to the overall cacophony. Hand grenades exploded steadily with dull thuds, muffled by the mud. Positions were abandoned, then retaken, again and again.

For five days, combat ebbed and flowed along the 45th Division front, with the American veterans, sometimes surrounded in pockets, fighting like demons. The Allied line bent back one and one-half miles but did not crack, and the 45th Division saved the entire perimeter from collapse. Pfc. William Johnston was manning a machine gun on the 18th when about 80 Germans came straight for his position. He cut down 25 of the enemy and killed two others who crawled so close to his gun that he could not depress it to fire accurately. At dawn on the 22nd, 2nd Lt. Jack Montgomery, a Cherokee Indian from Oklahoma, knocked out several enemy machine gun nests, killed 11 Germans, and captured 32 more. Both men received the Medal of Honor for their feats.

On the first night, the untried Infantry Lehr Regiment had been chewed to pieces before fleeing the field in disarray. A number of its soldiers were among the nearly 20,000 dead and wounded the Germans had suffered in three weeks. The 45th Division had lost 400 dead, 2,000 wounded, and 1,000 missing, and another 2,500 were rendered combat ineffective due to illness or exposure.

On February 22, Clark came to VI Corps headquarters and replaced Lucas with Truscott, the former 3rd Division commander. “I thought I was winning something of a victory,” complained Lucas, refusing to be second-guessed about his decision at the beachhead, although the ranks of his detractors included Churchill, Alexander, and several American commanders. “Had I done so [advanced quickly] I would have lost my corps and nothing would have been accomplished except to raise the prestige and morale of the enemy,” he wrote. “Besides, my orders didn’t read that way.”

Contained on the Beach

The 3rd Division bore the brunt of the fighting during the last major German counterattack intended to dislodge the Anzio beachhead. On the night of February 29, from Ponte Rotto to the Fosso della Crocetta, the Germans attacked. Some of the heaviest blows overran a forward company of the 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, with only one officer and 22 men able to fall back 700 yards to the main line. The positions of the 7th and 15th Regiments were assaulted by the 362nd, 26th Panzer, and Hermann Göring Divisions, supported by Mark VI Tiger tanks. Near Ponte Rotto, the 7th Regiment withstood heavy attacks, although at several points the Germans penetrated the lines and their tanks fired directly into the American foxholes. Thirty-five men of the 7th Regiment were killed on March 1 near Ponte Rotto.

The last major offensive against the Anzio beachhead cost the Germans 3,000 casualties and more than 30 precious tanks. Kesselring intended to contain the Anzio front to the best of his ability, and his artillery and Luftwaffe bombers harassed the Allied soldiers inside the battered perimeter day after day. A pair of gigantic 280mm railway guns, dubbed “Anzio Annie” and “the Anzio Express,” were as psychologically demoralizing as they were physically damaging. Bloody February stretched into stalemated March along the wreckage-strewn beach at Anzio.

Operation Diadem: Breaking the Gustav Line

Alexander, for his part, had seen enough fighting on a relatively narrow front. When the weather improved, he intended to extend the pressure on the Germans with an offensive, code-named Operation Diadem, at four locations along the Gustav Line. With a breakthrough there, the Allied forces at Anzio would launch an effort to break out of the beachhead and trap the German forces. At 11 pm on May 11, Operation Diadem began with a thunderous artillery barrage. More than 1,600 guns of the Fifth and Eighth Armies barked. The entire offensive jumped off during the following two hours. Along the II Corps line, American gains were minimal. No significant breakthrough was achieved. Combined with the limited British gains on the Rapido, the first 24 hours of Operation Diadem appeared to have achieved little.

The French Expeditionary Corps, under General Juin, had fortuitously been tasked with the advance across the Aurunci Mountains. So confident were the Germans that the difficulty of the terrain would dissuade any assault rather easily that they had placed fewer troops in the area than other parts of the Gustav Line. The Algerian and Moroccan soldiers of Juin’s command, however, were quite familiar with such rugged country. Within hours of their initial advance, the French troops occupied Monte Majo and raised the tricolor flag on its summit. The threat to the Germans at the Gustav Line was painfully obvious. The 71st Infantry Division had been cut in two, while the left wing of the XIV Panzer Corps was now open to attack. The potential existed for continued advance across ridges running to the northwest, and the French were positioned to attack the right flank of the German positions in the Liri Valley, giving a decisive boost to the Eighth Army just beyond the Rapido. The French might also knife into the Liri Valley and trap many of the Gustav Line defenders.

While Kesselring scrambled to reinforce the 71st Division, the British managed to throw a third bridge across the Rapido and expand their bridgehead up to 2,500 yards. Renewed attacks by elements of the American 85th and 88th Divisions were held up by entrenched defenders on high ground at Hill 109 and Hill 131, but after dark, the American troops were surprised when a subsequent advance encountered only sporadic small-arms fire. The Germans were pulling out.

On May 15, the Eighth Army succeeded in breaking through the Gustav Line in the Liri Valley. The Eighth Army advance of the 15th was followed with a joint attack against Cassino by the 78th Division and the Polish II Corps to cut Highway 6 and capture Monte Cassino. Swiftly, the German positions at Cassino became untenable, and the 1st Parachute Division was pulled out of the ruined abbey.

Hesitation on the part of the German high command, including Kesselring and Hitler in far-off Berlin, contributed to the collapse of the Gustav Line. General Walter Hartmann, the acting commander of the XIV Panzer Corps, realized that substantial reinforcements would be necessary to contain the Allied breakthrough at three separate points. The failure of German intelligence to assess accurately the strength of the Allied armies confronting the Gustav Line defenses, coupled with the threat of another amphibious landing in the vicinity of Rome, kept Kesselring off balance. With such a slow response, it became increasingly unlikely that the Germans could maintain defensive positions south of Rome.

By May 20, the French Expeditionary Corps had punched a hole in the Hitler Line, a string of German fortifications 10 miles north of the Gustav Line. The advance of II Corps toward Anzio was proceeding at a reasonable pace, and on the 23rd the Canadian 1st Division breached the Hitler Line northeast of the town of Pontecorvo.

The situation in southern Italy was clear to the German commanders. II Corps was in position to advance smartly up Highway 7 to effect a junction with VI Corps at Anzio, while the Eighth Army was through the Hitler Line and well into the Liri Valley. The French Expeditionary Corps threatened to complete the encirclement of portions of two German armies, the Fourteenth and the Tenth, and its advance toward the town of Frosinone, astride Highway 6, might actually split the armies in two. Vietinghoff issued orders for a general withdrawal on the German southern front. The LI Mountain Corps vacated its positions opposite the Eighth Army, falling back to the north along several roads parallel to Highway 6. The XIV Panzer Corps withdrew to the Sacco River valley northeast of Pico.

Alexander’s Operation Buffalo

During four months of agony, the VI Corps had languished within the perimeter of the Anzio beachhead. Its strength had grown from two divisions to seven. However, the beachhead was under the constant surveillance of Germans in the Alban Hills. Any appreciable movement during daylight was certain to bring down accurate artillery fire. Some Allied soldiers remember an absolute inability to move about during the day and the necessity of feeding the men under cover of darkness. Often the identities of replacements put into the line were known only vaguely to their noncommissioned officers.

Although the high hopes with which Operation Shingle had been launched in January were only a distant memory by the spring, a good measure of the scant resources available in the Mediterranean Theater had been allocated to the beachhead in preparation for the opportune time to launch a decisive effort to break out. With the forceful Truscott in command following the relief of Lucas, Alexander expected success. Clark had ordered Truscott to prepare for any of four eventual axes of attack. The one that aligned with Alexander’s plan, Operation Buffalo, was to strike northeast through Cisterna to Valmontone, cutting Highway 6 and hopefully trapping a large number of German troops to the south. In this scenario, the capture of Rome would be a secondary consideration to the opportunity to deliver a crippling blow to enemy forces in Italy. Alexander had originally advocated a movement to the north, through the natural barrier of the Alban Hills, and on to Rome, but the prospect of cutting off large numbers of German troops appeared to be of greater benefit to the Allied cause. Since the two directions of attack were at least 20 miles apart, it appeared to Alexander that they could not be accomplished simultaneously.

The “Only Worthwhile Objective”

Clark, however, had his eyes firmly fixed on Rome. He doubted that the seizure of Highway 6 would accomplish much in the way of deterring a German withdrawal over numerous secondary roads in the area of Valmontone. Clark maintained that moving on Valmontone was designed primarily to relieve pressure on the Eighth Army in the Liri Valley. Still, if Clark could make contact with VI Corps, Truscott might move rapidly northward through the Alban Hills and on to Rome. The Fifth Army commander desperately wanted American troops, not British, to capture the Eternal City. And time was of the essence. Rome had to fall before Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, took place on June 6 and once and for all relegated the Mediterranean to a backwater.

Clark believed, not without reason, that an enemy force anchored on the Alban Hills posed a threat to any eastward movement by the Fifth Army. He stressed that the Alban Hills should be secured before a drive to Valmontone. Logically, it followed that if the Alban Hills, the last natural barrier south of Rome, could be taken, then Rome itself would follow. VI Corps would be the spearhead of Fifth Army’s drive to take the Italian capital. Clark, like other Allied commanders and the British prime minister himself, regarded the city as the great prize of the Italian campaign. He told Truscott that it was the “only worthwhile objective” for VI Corps. Clark had only an incidental interest in the military value of the Italian capital—he wanted it because of the prestige associated with capturing it and because, in Clark’s opinion, the Fifth Army had borne the brunt of the fighting and deserved the honor of capturing Rome.

On the night of May 22, the British 1st Division launched the breakout from the Anzio beachhead with a diversionary attack along the Anzio-Albano road. In the early morning hours of the 23rd, Combat Commands A and B of the U.S. 1st Armored Division launched the main attack. During the first day, the two commands crossed the railroad line to Rome and drove a mile into the defensive perimeter of the German 362nd Infantry Division. They had also reached their first primary objective, a low ridge situated north of the beachhead. The cost was 35 dead, 137 wounded, and one missing. Three soldiers, Technical Sergeant Ernest H. Dervishian, Staff Sergeant George J. Hall, and 2nd Lt. Thomas W. Fowler, received the Medal of Honor for gallantry on May 23.

Taking Cisterna

The attack on Cisterna was launched by the 3rd Infantry Division at 6:30 am. A task force led by Major Michael Paulick was assigned to cover a gap caused by necessary maneuvers between the 15th Infantry Regiment and the 1st Special Service Force. Paulick lost two tanks and a tank destroyer to German fire from a group of houses 600 yards beyond a bridge over the Cisterna canal. He directed three tanks on a wide arc into the enemy rear, and this concentrated fire routed the Germans. Moving ahead against light resistance, Paulick’s task force advanced to within half a mile of Highway 7. After dark, a three-man regimental patrol detected the movement of about 60 German soldiers into a wooded area near a road junction. The Americans retired and passed the word up the line. An ambush was prepared, and the German force was decimated, with 20 killed and 37 taken prisoner.

Two battalions of the 15th Infantry Regiment worked their way toward the town of Cisterna. The 7th Infantry encountered difficulties with mines and stiff German resistance. The 30th Infantry also had trouble with mines, and progress was sluggish. The 3rd Division had lost 107 dead, 642 wounded, and 812 missing, and 65 had been taken prisoner. Although there had been no decisive breakthrough against German positions, Clark and Truscott were encouraged that the day’s gains were significant and would lead shortly to the capture of Cisterna. Against strong opposition on the 24th, the 3rd Division surrounded Cisterna, but an attack against its north flank was unsuccessful. Supported by tanks, troops of the 7th Regiment managed to enter the town the following morning.

Near daybreak on May 25, combat engineers of the 36th Division, moving south from Anzio across the Mussolini Canal, made contact with an 85th Division task force. After 125 frustrating days, VI Corps was no longer isolated. Now, it was the left flank of the Fifth Army. On that same day, Clark issued a controversial order shifting the VI Corps axis of attack northwest toward Rome. While the 3rd Division and the 1st Special Service Force continued eastward toward Valmontone, the bulk of the Fifth Army—the 34th, 36th, 45th, 85th and 88th Divisions—was to drive for the Italian capital.

Rome Falls to the Allies

On the morning of June 3, Kesselring declared Rome an open city. A day later, elements of both II and VI Corps finally entered Rome, which became the first Axis capital city to fall to the Allies. Operation Diadem had succeeded in breaking the back of the stubborn German defenses in southern Italy. In a little more than three weeks, the Fifth and Eighth Armies had driven the Germans from the Gustav Line, linked up with the Anzio beachhead, and captured Rome. The price had been high. Allied casualties totaled nearly 44,000, while the Germans had suffered more than 38,000 plus 15,600 taken prisoner.

In a note of supreme irony, German forces were too weak to contest a drive to Valmontone by VI Corps, even by a secondary effort. Had Clark continued northeastward as Alexander had directed and cut Highway 6, his forces would probably have reached Rome more quickly than they did by hammering directly at the Caesar Line. As it was, German Army Group C had been battered and beaten, but it had not surrendered or been destroyed. The fighting in Italy would continue for several more months. However, after an initial splash of headlines celebrating the fall of Rome, the eyes of the world turned to Normandy. On June 6, the longest day of the war dawned on the coast of France, and the brutal if underpublicized campaign in Italy exited center stage for good.

My uncle Eugene A Crump was.trained in both anti aircraft artillery and Coastal and anti ship artillery at the Panama Canal before WW2; He had been given an unfit for Military duty due to his severe malaria that had cut his weight from 180 pounds to 140 pounds and sent home in Nov 1941 prior to his discharge date of 1 January 1942. He was ordered to report to Camp Edwards MA on my 14 dec birthdate and was never allowed to leave the base a free man. His task was to train the VT National Guard REgt. with the new 90 mm copy of the German 88, to also train the defense for these cannons with jeep mounted dual 50 caliber machine guns for the N African invasion where they landed in French Morocco which due to its being a neutral nation had to be passed thru in 48 hours. He then went thru the African campaigns, landed at Sicily and Salerno followed by his landing as artillery support at Anzio, was in lead group entering Rome followed by Operation Dragoon landing in Southern France and going all the way up the Rhone River to the Saar Valley and then to support the 36 Texas at Colmar where Audi Murphy called in their new proximity shells onto the Germans from his disabled tank. His group served under Patton, Truscott, Clark, Patch, Hodges and some others all the way into Germany. The railroad guns at Anzio were called Gustav guns and duds even shook the bunkers. He also told Clark how to shoot down the ME 162 that attacked the beachhead at Anzio each evening from its catapult launch site at the railroad to drop a bomb onto the beachhead. The limited flight time rocket plane was too fast for the pilot to accurately drop the bomb but was doing a lot of pyschological damage. Gene told them to have each gun point to a point in the sky and start firing when the attack warning light turned on. The rocket plane ran into a cloud of projectiles and crashed into the surf on the beach where it was immediately pulled from the surf by an LST that took it away for study. Rome could have been easily captured the second day of the invasion had the invasion troops been allowed to proceed up that highway to Rhome which was undefended until the third or fourth day. Monte Cassino had German artillery directors in it almost from the start of the invasion. The so called civilians were people the Germans were using to increase the defenses and to help run telephone lines to the German batteries around the beachhead. Any true civilians would have been forced to leave initially to save food and water supplies. Truscott, Patch, Patton, and Hodges were thought by the troops to be excellent commanders; Clark was only considered a slow plodder who always took the safest tack at the expense of taking advantage of good events to gain objective.

I joined the 36 Div., 142 Regiment, TX National Guard in 1953. Even 10 years after the fact Mark Clark was the most hated man in the Army. His ineptitude cost thousands of lives. If the families of the men lost could have gotten their hands on him it wouldn’t have been pretty.

Nice map. Good article.