By Peter Suciu

Modern military camouflage has gone high tech, with digicam or “digital camouflage” being the preferred pattern for soldiers in the field. This utilizes small micro-patterns for effective visual disruption, as opposed to large blotches of cover that could be easier to spot with the naked eye, representing a considerable advance over the first methods of camouflage, which consisted of solid patterns. Among the earliest was khaki, which has a long history as the first widespread military camouflage.

In England, gamekeepers first adopted drab colors to hide from game and poachers. By the time of the Napoleonic Wars, British rifle units such as the 95th Rifles were outfitted in green jackets, as opposed to the familiar scarlet uniforms of the day. In fact, the legendary British “red coats” dated back to Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army and were based on the traditional colors of the Yeomen of the Guard and the Yeomen Warders. While there is a common myth that red coats were favored because they did not show blood stains, it is likely pure fiction—blood does show up on red clothing as a dark, even black, stain. Red is the color of the Tudor Rose, and the earliest red coats were worn with white trousers to honor the Royal house. The original Union flag of the United Kingdom was also red and white.

British Army Uniforms: From Red Coats to Khaki

As the British Empire expanded, it soon became apparent that red or scarlet tunics were ill-suited for the tropical climate of the Indian subcontinent. Likewise, the heavy wool uniforms were simply too hot to wear. And yet for the better part of 70 years, the British Honorable East India Company, as well as regular army troops serving in India, retained their scarlet uniforms. According to author Stuart Bates in his book The Wolseley Helmet in Pictures: From Omdurman to El Alamein, Sir Harry Lumsden raised a Corps of Guides in 1848 for frontier service at Peshawar, near the Afghan border in Pakistan. These troops wore a uniform based on their own native attire rather than the British Army’s scarlet tunics. This consisted of a dust-colored smock and white pajamas.

Originally, the Guides’ uniforms were anything but uniform, but eventually the fabric was dyed with mulberry juice, giving it a yellowish drab color that closely matched the local soil. Accordingly, it was named for the color of soil, using the Persian word khaki, meaning “dust.”

Khaki was adopted by other British-Indian regiments during the Indian Mutiny of 1857, but was discontinued until 1868. What prompted the British to briefly abandon the color is not fully understood, but one theory holds that the color was not consistent. In fact, over the years numerous attempts were made to formulate a dye that would provide a khaki color that was consistent and would not fade or run. These attempts failed, with the uniforms varying greatly in color after only a few weeks or months of exposure to the weather. And while khaki uniforms made a return in India, British soldiers serving in the Zulu War (1879), the First Anglo-Boer War (1882), and the First Sudan Campaign (1882) retained their scarlet uniforms. However, by the end of the 19th century, the red coat was replaced everywhere by khaki.

It was commonplace for troops to stain their white uniforms and helmets with any appropriate substance to break up the white and therefore provide some camouflage. A variety of materials, including mud, tea, coffee, tobacco juice, and even curry powder were used. The problem was solved when a fast-acting dye was patented, one that produced a consistent yellowish-brown color that could be retained over a prolonged period. “During this period it was a grayish color drill fabric but when the British Army adopted it for the Second Boer War of 1899-1902,” explains author Nigel Thomas, “it had become a light yellowish brown, the color through the two world wars until the present day for tropical uniforms.”

The color evolved from the tan-colored dust and became darker brown. In 1924 the new shade was formally introduced; it was slightly greener than the one it replaced. “The British Army adopted khaki serge for its service uniform in 1902 and for the battledress field uniform 1939-1962,” says Thomas. “Khaki serge was a much heavier fabric than khaki drill and was intended for fighting in winter in northwest Europe. It was a darker greenish brown, the amount of green depending on regimental tradition.”

French and Italian Khakis

The use of khaki was not limited to the British Army. By the end of the 19th century, most of the nations of Europe with colonies overseas had begun to utilize similarly colored tropical uniforms. In many cases, officers and NCOs were outfitted in European-style uniforms, while colonial troops wore khaki-colored ones. Many of these colors were never officially deemed khaki, but the colors were extremely close in actual practice.

French Foreign Legion and French Marine Infantry were outfitted with a tan-colored corduroy or “moleskin,” which had a brownish color. During the interwar period, the color was lightened and officially became known as khaki, only to be replaced in the postwar era by olive-drab uniforms. France was not alone in following the British use of khaki; the Spanish and Portuguese also adopted the look. The Italians wore a similar color in their late grab for colonies in Africa and throughout World War II.

German Colonial Khaki

Germany too utilized its own take on khaki, even if it was late to adopt it. For use in Europe, the German Army adopted a field gray uniform that proved to be as unsuitable in Africa as British scarlet had been in India. The Germans turned to tan-based uniforms. “As with their colonies, the Germans were late comers to the use of khaki, mainly because they didn’t fight abroad until the 1880s” explains British militaria collector Chris Dale, who has written on the subject of German colonial uniforms. “The first use of khaki was the Wissmanntruppe in 1889 in East Africa, while in 1891 the Schutztruppe uniform regulations refer to that color as ‘Khaki Brown Drill.’”

Dale supports the theory that the Germans essentially copied the British color. He adds that the use of khaki spread to all German colonies and military outposts, including those in the Pacific, Africa and China, and was further used in the Balkans and Palestine during World War I. During the latter conflict, khaki was used on European battlefields by both sides, and in East Africa the British, South African, Portuguese, and Belgian forces faced off against the Germans in similar shades of khaki.

As with the British uniforms, the Germans made many variations of colors and shades, in part because of the complexity of the German colonial administration and the various branches of service that oversaw the colonies and their respective defense. “The Germans in South West Africa also used brown corduroy uniforms, not strictly khaki but a shade called ‘Sand Color’ in the regulations,” says Dale. “In fact, the corduroy they used varied from pale khaki to a grayish brown, and it was used from 1889 onward.”

If the Germans hadn’t copied the British color or patterns, they did rely on British fabric. Dale adds, “The first corduroy used by the Germans was made in the cotton factories of Lancashire, U.K.” He says that later the Germans made their own corduroy and adds that the German tropical uniforms may have had another use after the war. There is a common theory that the early Nazi party, the so-called Brownshirts, actually wore German military surplus and that the Nazis simply reused the Schutztruppe khaki uniforms. “I’ve never seen any proof of it,” says Dale. “And if they did it would only have been the reams of the cloth, as the cut of the two uniforms was quite different.”

It was not the last time that the German military adopted a khaki uniform; the Afrika Korps in World War II was also outfitted in tropical uniforms. As it quickly became apparent that the German Army would be involved in the Mediterranean and Middle East, the Tropical Institute of the University of Hamburg was called upon to design a new uniform. Thomas notes in his book, The German Army 1939-45: North Africa & Balkans, that these were based on the German colonial uniforms used until November 1918, and that “most items of the M1940 tropical uniform were manufactured in ribbed heavy cotton twill or cotton drill.” He describes the color as light-olive. This evolved into the sandy brown or tan M1941 pattern uniforms that were used not only in North Africa, but throughout the Mediterranean and the Balkans.

The Japanese M1904 Khaki Uniform

Halfway around the world, the Empire of Japan was outfitted in a similar shade of khaki uniform, one whose origins went back to the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The Japanese had replaced their white cotton summer uniform in 1904 with the new M1904 khaki uniform, which likely was inspired by the colors used by its then close ally Great Britain. The uniform was used throughout World War I, then modified and modernized in 1930, but retained the same color as the tropical, or summer, uniform throughout World War II.

Ironically, the British found that khaki was impractical for use in the jungles of Burma and instead dyed their uniforms green while exploring options for more suitable jungle uniforms. The result was Jungle Green (JG), which had a significant flaw in that it darkened quickly as soldiers sweated through the cotton uniforms. The French experienced a similar flaw when they replaced khaki with American Olive Drab (OD) for use in Indochina in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

U.S. Army “Chino” Style Uniforms

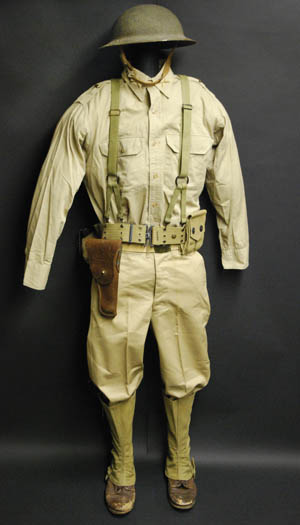

The American military first adopted khaki for use during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Until that time, the United States Army was outfitted with the M1883 fatigue blouse in blue. However, the large numbers of volunteers—and the fact that soldiers were falling prey to heat exhaustion and dehydration—forced the Army to experiment with lighter-colored and lighter-weight materials. The United States thus adopted the khaki cotton drill, and in 1903 the Army authorized it as soldiers’ official hot weather fatigue and field dress.

The American use of khaki continued after World War I in tropical climates, notably by the United States Navy and Marine Corps. The United States Army also utilized a khaki field uniform, the “chino” style, until the outset of World War II as the summer service and field dress. It was replaced by specialized combat uniforms and only briefly saw use with Army units in the Pacific. However, the khaki did have its influence on the M41 field jacket, which retained a khaki shade before being replaced with the Olive Drab M43 field jacket.

The Marine Corps has retained khaki as its training and walking out uniform, while khaki remains in use with the United States Navy for chief petty officers and officers, who are often called “khakis” by the enlisted men. While no longer practical as camouflage, khaki still has a place with other nations as a walking out uniform and also as part of a shared history of military uniforms. Few patterns or colors have been as widespread as khaki, the color of Indian dust. n

Actually Rogers Rangers in the French & Indian wars in North America was the first widespread use of camouflage. They wire green dyed buckskins. Another example of early use was the butternut uniforms worn by confederate soldiers in the American Civil War. They were unintentional and were the result of poor dyes used in making the uniforms.