By Lawrence Weber

Sunday morning, March 23, 1862, was sunny and warm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, a devout Christian, did not like to fight on the Lord’s Day. “The enemy could be destroyed tomorrow,” he reasoned. “The peace of the Lord would not be violated.” Still, the sun and warmth were a welcome relief for Jackson and his vaunted “foot cavalry,” who for several days had been braving high winds, cold temperatures, and hard rain in endurance-draining marches northward through the Shenandoah Valley. Some days they covered as many as 21 miles.

The destination of their exhausting marches was Winchester, Virginia, where soldiers from the Union Army of the Potomac’s V Corps were located, but Jackson and his men did not make it there. Instead, Jackson halted his men at Kernstown, a few miles south of Winchester. He wanted to rest his men, continue the march the next morning, and engage the enemy on Monday instead of Sunday. Unfortunately for Jackson, things did not work out quite the way he planned.

“Jackson’s Gone! Jackson’s Gone!”

During the previous few weeks, tensions had been high between Union and Confederate soldiers stationed in the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson’s forces, which previously had been camped in Winchester, had been forced to move around a great deal. Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks had been following orders from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, to disrupt and remove Jackson’s forces and secure the Shenandoah Valley for the North. When Banks and the men of V Corps approached Winchester in early March, Jackson had intended to fight to maintain his position there. After all, this was familiar ground for Jackson, and he felt confident that he could be successful there.

Unfortunately for Jackson and his men, badly needed supply wagons with rations and muskets for the soldiers had been taken to the wrong location in Newtown, roughly eight miles south of Winchester, just as Banks’s V Corps was closing in on the town. The grim news and poor timing forced Jackson to make a difficult decision. With the arrival of Banks’s men, without supplies and rations, and seriously outnumbered, Jackson felt that he had to withdraw from Winchester without a fight. He was distraught at the decision, telling a local clergyman: “This I grieve to do. I must fight,” he said, drawing his sword halfway out of its scabbard for emphasis. But he surrendered to the inevitable. “No, it will cost the lives of too many brave men,” he said. “I must retreat. Nothing but necessity and the conviction that it will be for the best induces me to leave.” Under cover of darkness, Jackson and his men began their retreat from Winchester. A small boy accompanied them part of the way, crying out: “Jackson’s gone! Jackson’s gone!”

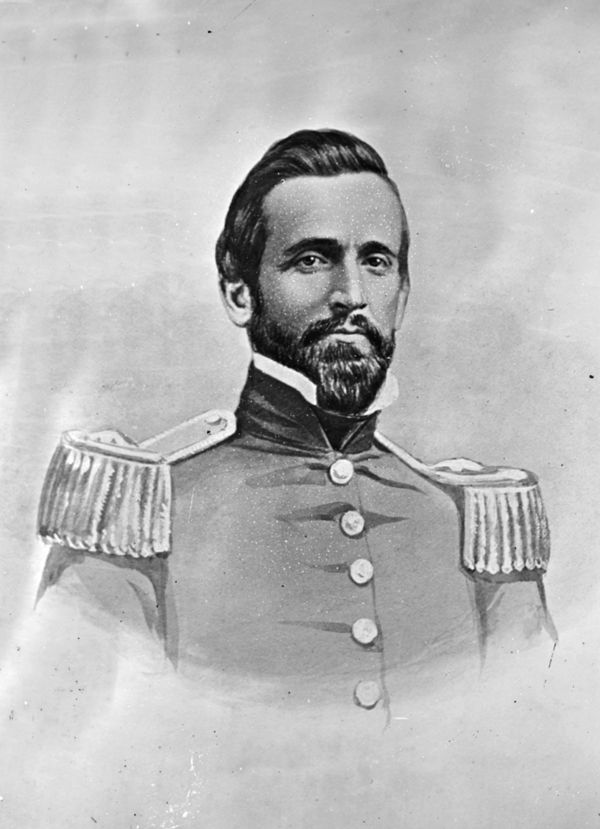

Jackson marched from Winchester to Strasburg, 18 miles away. There, the men set up camp for several days and were able to resupply themselves with a limited amount of essential items. Unfortunately for them, the equipment was poor and the men remained fatigued. At any rate, their stay in Strasburg was short. While Jackson was deciding on his next move, Banks was ordered to detach a division of 9,500 men under the command of Brig. Gen. James Shields to pursue Jackson southward through the valley. As Shields and his men closed in, Jackson recognized the same type of threat he had faced at Winchester and came to the same conclusion. On March 15, Jackson and his men left Strasburg and continued to search for a more strategically situated piece of ground.

Jackson found a new location at Rude’s Hill, three miles south of Mt. Jackson. Rude’s Hill was an excellent defensive location, and it was there that he established camp. On March 19, he set up his headquarters near the settlement of Hawkinstown, three miles north of Mt. Jackson. Utilizing the geography allowed Jackson to assess the situation in the valley, which provided him with an opportunity to figure out what to do next. At Rude’s Hill, he began to get word of a larger plan that was unfolding regarding the movements of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan was poised for a major assault on the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Jackson’s Decision to Intercept Banks

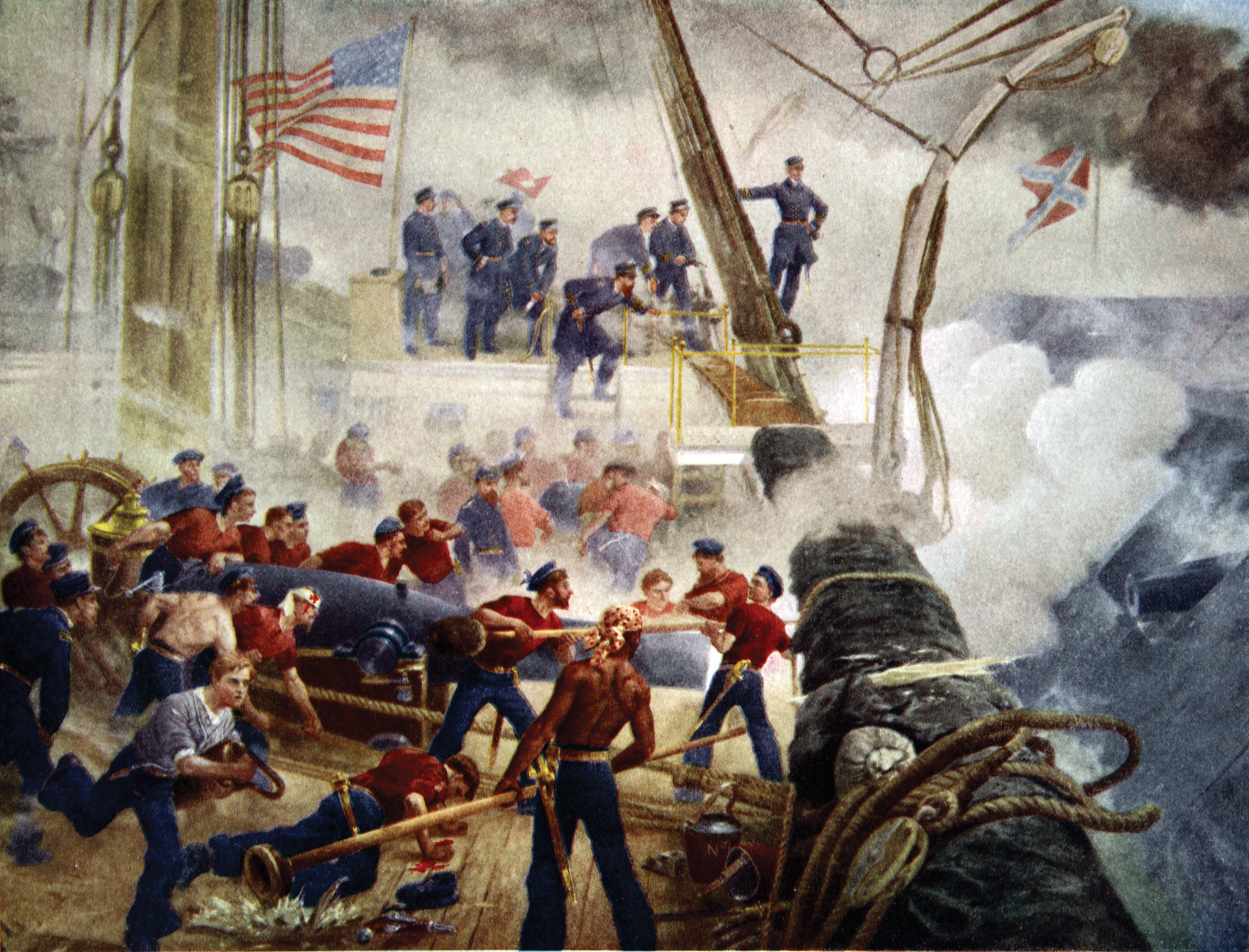

McClellan’s plan was a sound one. Using the United States Navy in tandem with the Army, McClellan wanted to land on the Virginia Peninsula and march west toward Richmond, with the Navy providing protection of the Army’s flanks along the York and James Rivers. If his plan was successful, McClellan would be hailed as the savior of the Union. “The moment for action has arrived, and I know that I can trust in you to save our country,” McClellan informed his men.

McClellan felt that Banks and his men had done an excellent job of dislodging the Confederates from the Shenandoah, specifically from the Winchester and the Manassas Gap Railroad areas. Believing that these areas were secure, McClellan instructed Banks to begin moving eastward across the Blue Ridge Mountains to join forces for an all-out assault on Richmond. McClellan ordered Banks to leave several regiments behind to guard the railroad bridge and to provide protection to V Corps. Banks ordered Shields to remain in the valley with several divisions.

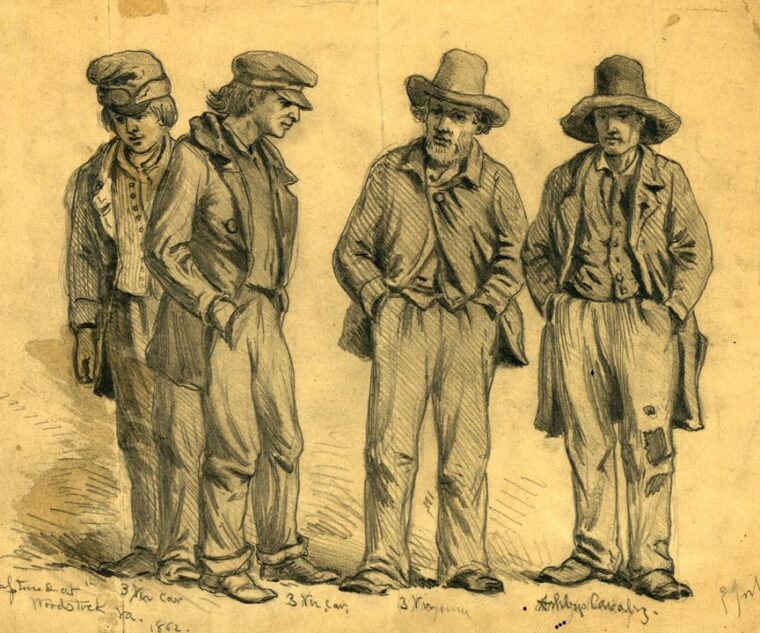

According to reports from Jackson’s cavalry chief, Colonel Turner Ashby, Banks’s entire army was leaving the Valley to join forces with McClellan on the Virginia Peninsula. On Saturday evening, March 22, Ashby and his men began to skirmish with Union forces in the Winchester and Kernstown areas in an attempt to disrupt the movements of V Corps. After receiving the report from Ashby, Jackson felt that together they could attack the reduced Union forces stationed around Winchester and possibly disrupt Banks’s march toward McClellan on the peninsula. Unfortunately for Jackson, Ashby’s information was incorrect. What Ashby reported as a limited Union force was actually a full division of 9,500 men, intent on securing the Shenandoah and providing cover for Banks’s men.

If Banks was successful in linking up with McClellan, they might launch an assault on Richmond that could end the war. Jackson felt that his only options were to either intercept Banks before he could join forces with McClellan or else cause a major disruption in the Shenandoah Valley that would pull forces away from McClellan, threaten Washington, and stall the campaign on the Virginia Peninsula. For Jackson, it was time to march back to Winchester and fight.

“I Determined to Advance at Once”

Early in the morning of March 23, Jackson and his men began their march toward the Winchester area. Covering roughly 15 miles through the valley, Jackson halted the advance around 2 pm, one mile outside of Kernstown and three miles south of Winchester. He ordered his men to set up tents. All the regiments except for Colonel John A. Campbell’s 48th Virginia, which was the rear guard, arrived within a mile or two of Kernstown that afternoon. Jackson originally had no intention of engaging the enemy on the 23rd, but additional information presented to him during the morning march caused him to reconsider. Ashby passed along word from usually reliable Winchester sources that the Federals had only four regiments left inside the town and that even those forces were planning to withdraw shortly to Harpers Ferry.

Even so, Jackson felt that attacking the enemy immediately was not the most prudent decision; early Monday morning would be better. But when Jackson and his men arrived outside Kernstown, he noticed that their positions were visible to the Union soldiers on the opposite heights and therefore they were already compromised and vulnerable. “I concluded that it would be dangerous to postpone it until the next day, as re-enforcements might be brought up during the night,” Jackson reported afterward. “I determined to advance at once.”

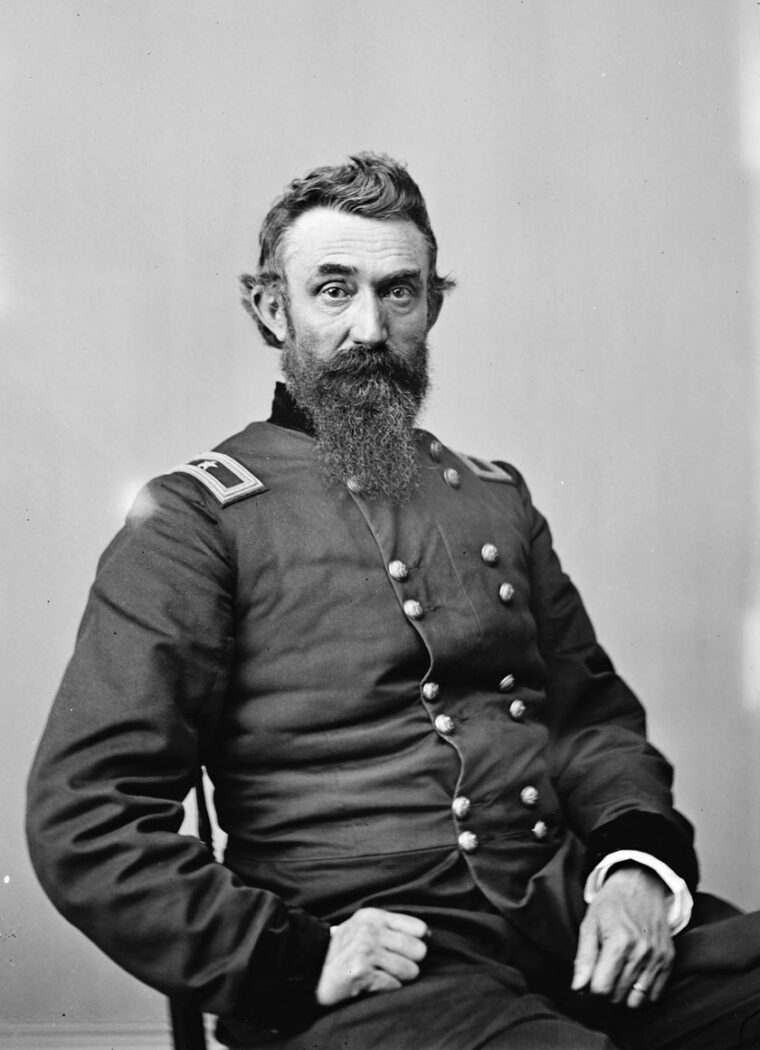

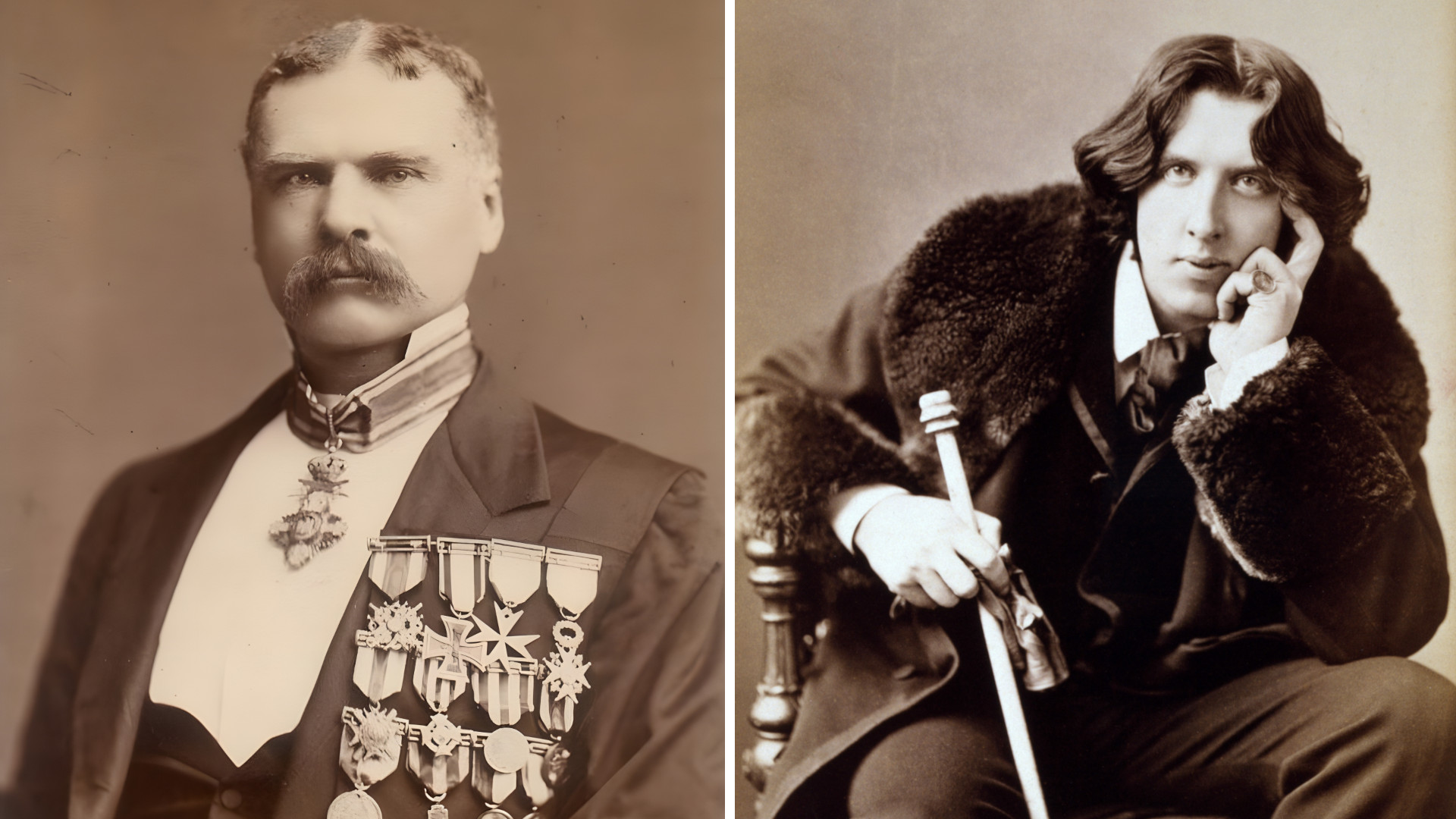

The Union side of the battle would not, in fact, be commanded by Shields. The day before, Shields had been severely wounded in a skirmish with Ashby’s men when an artillery shell exploded nearby and a fragment struck Shields in the upper arm, breaking the bone. The wound was severe enough to cause Shields to leave the field. Senior regimental officer Colonel Nathan Kimball, an Indiana physician, took command of the division. Kimball, like Shields, was an experienced Mexican War veteran, a hero of the Battle of Buena Vista, but he would be the third divisional commander in three weeks. (The original commander, Brig. Gen. Frederick Lander, had died of illness on March 2.) It was unclear whether he could handle his men competently.

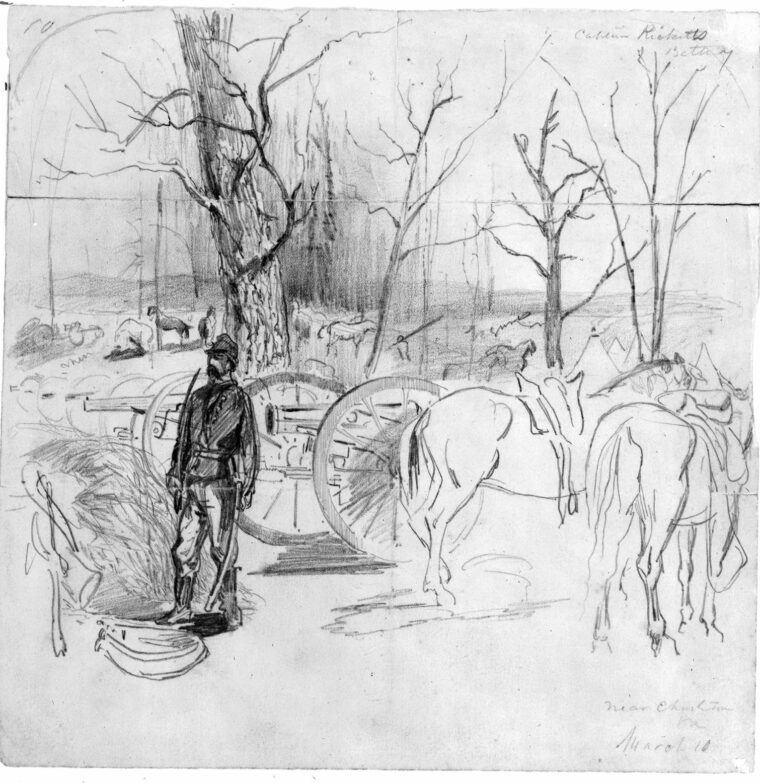

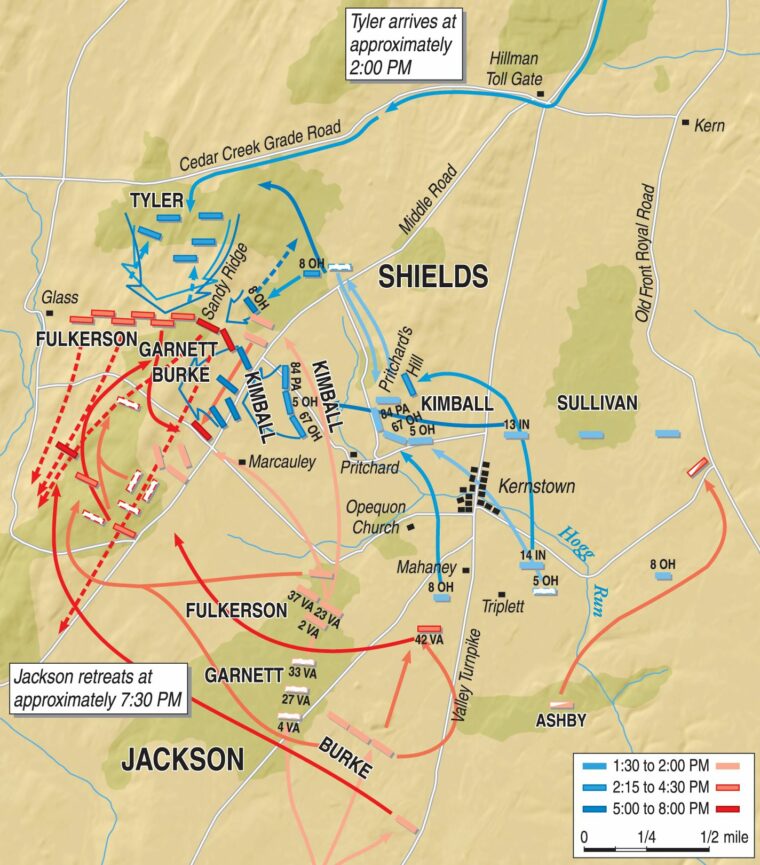

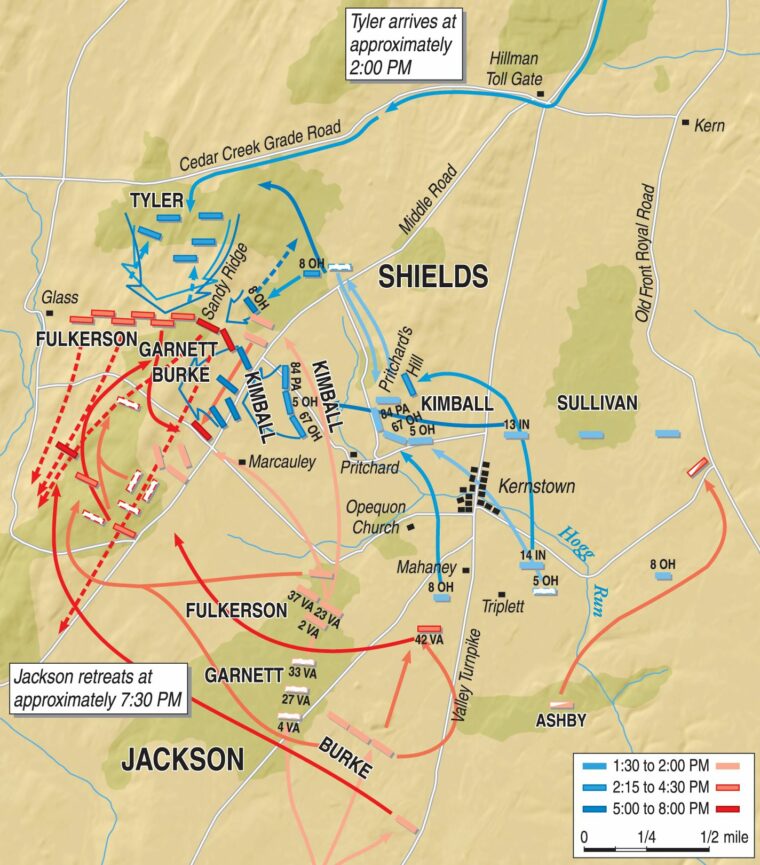

Early in the morning of the 23rd, Ashby’s forces renewed the attack, advancing from Kernstown and occupying a position with their artillery batteries on the heights to the right of the Valley Turnpike leading into Winchester. Ashby attempted to turn the Union flank, but Kimball proved up to the task of command, directing the 8th and 67th Ohio Regiments to meet the Confederates head-on. His men held strong, driving the Southern forces back through Kernstown and uncovering the only high ground in the area, a small knoll called Pritchard’s Hill. Immediately realizing the hill’s importance, Kimball stationed the 1st Brigade and two batteries of artillery on the crest and moved another brigade to the left of the hill. A third brigade was held in reserve in the rear, out of sight of the approaching Southerners.

Confusion at Pritchard’s Hill

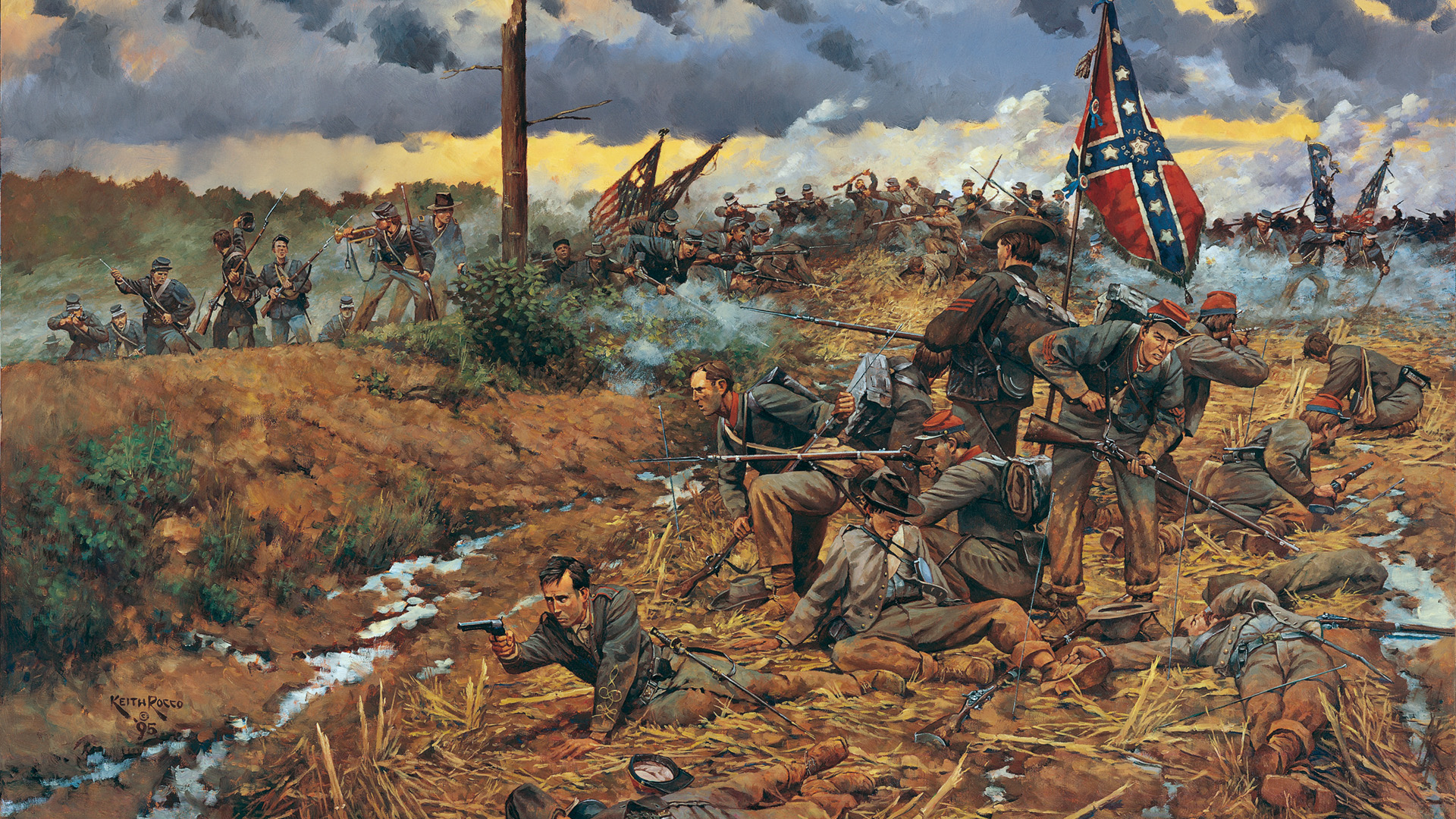

Jackson arrived at Kernstown in mid-afternoon and conferred with Ashby, who continued to assure him that only a small Union force held Pritchard’s Hill. Breaking one of his own rules, Jackson did not personally reconnoiter the field but accepted Ashby’s report at face value. It was a crucial mistake. Around 4 pm, Jackson unleashed an attack on the Union left, whose commanding feature, the six-mile-long Sandy Ridge, was covered by dense forest and fronted by a shallow stream, Hogg Run. Jackson sent some of Ashby’s men forward to skirmish along the stream while the rest of the cavalry and Jackson’s three infantry brigades wheeled left and headed for the woods flanking Pritchard’s Hill.

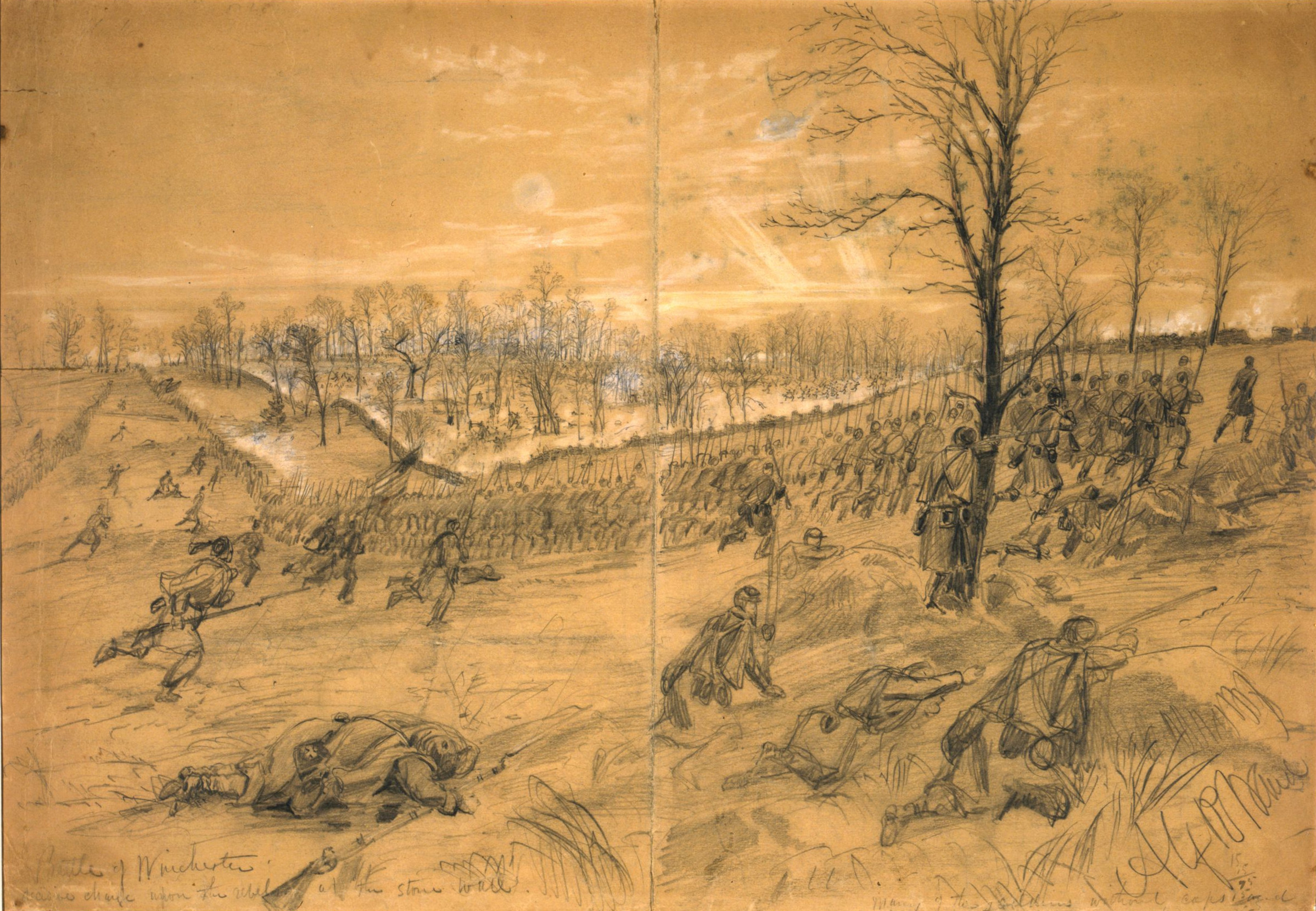

The Confederate attack began to unravel from the start. Jackson’s lead brigade, commanded by Colonel Samuel V. Fulkerson, ran into heavy Union artillery fire and took shelter—ironically—behind a stone wall. There, Jackson reported, his men “opened a destructive fire which drove back the Northern forces in great disorder after sustaining a heavy loss, and leaving the colors of one of their regiments upon the field.” It should have been enough to drive away a Union brigade. The only problem was that there were three Union brigades in the vicinity, and one of them, commanded by Ohio-born Colonel Erastus B. Tyler, moved up to support their embattled comrades.

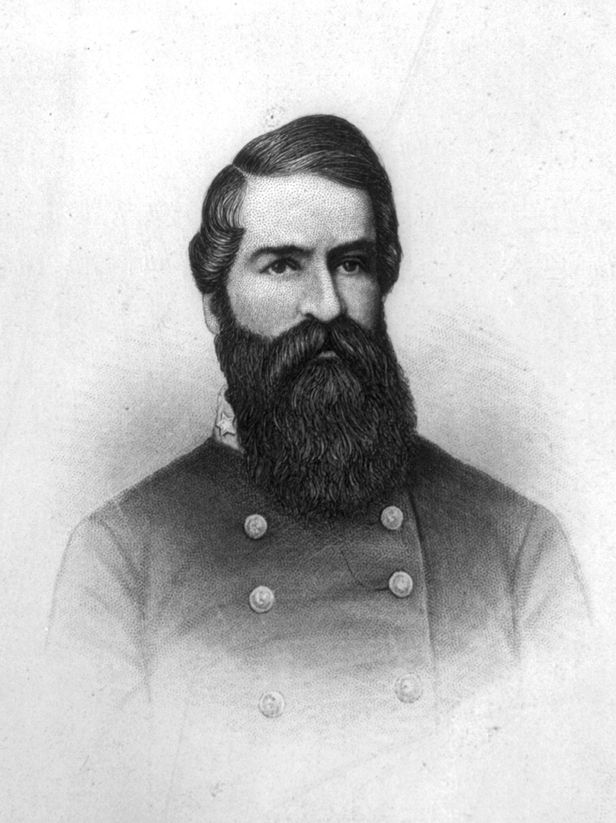

In the meantime, confusion reigned on the Confederate side. Jackson’s second in command, Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett, was commanding the famed Stonewall Brigade, which was supposed to be kept in reserve while Fulkerson cleared out the supposedly small enemy force. Jackson had not bothered to brief Garnett on his overall battle plan, perhaps expecting to make short work of the Federals, and Garnett accordingly was holding to a slower pace in the rear of the assault. Frustrated by what he considered the tardy progress of his namesake brigade, Jackson ordered one of the regiments to hurry to Fulkerson’s support. While Garnett went to make the dispositions, Jackson abruptly ordered the entire brigade forward.

Subordinate officers, unsure of whether to obey Jackson or Garnett, dawdled. Men wandered about desultorily while their officers sent back aides to clarify their instructions. During the interval, Jackson thought that his men were actually breaking through the Union lines and carrying the field. Suddenly, a massive explosion occurred to Jackson’s left, and Federal artillery came pounding into the center and left of Jackson’s lines. Jackson knew that he was in trouble. Attempting to assess the trouble, he sent a member of his staff, Sandie Pendleton, to find out where the extra Union artillery was coming from. Pendleton reported back to Jackson that the enemy did not have four regiments on hand, but at least three times that number. Jackson responded, “Say nothing about it, but we are in for it.”

Kimball described the surprise artillery attack from the Union point of view: “At this juncture I ordered the Third Brigade, Colonel E.B. Tyler, Seventh Ohio, commanding, composed of the Seventh and Twenty-ninth Ohio, First Virginia, Seventh Indiana, and One hundred and tenth Pennsylvania, to move to the right to gain the flank of the enemy, and charge them through the wood to their batteries posted on the hill. They moved forward steadily and gallantly, opening a galling fire on the enemy’s infantry. The right wing of the Eighth Ohio, the Fourteenth and Thirteenth Indiana Regiments, Sixty-seventh Ohio, Eighty-fourth Pennsylvania, and Fifth Ohio, were sent forward to support Tyler’s brigade, each one in its turn moving gallantly forward, sustaining a heavy fire from both the enemy’s batteries and musketry. Soon all of the regiments above named were pouring forth a well-directed fire, which was promptly answered by the enemy, and after a hotly contested action of two hours, just as night closed in, the enemy gave way and were soon completely routed, leaving their dead and wounded on the field, together with two pieces of artillery and four caissons.”

“Beat the Rally!”

In the center of the storm, the men of the Stonewall Brigade found themselves literally engaged in the fight of their lives. Taking positions to the right of Fulkerson’s men at the stone wall, Garnett’s brigade helped turn back repeated Union attacks—only to run out of ammunition as the afternoon waned. Confederates began drifting rearward in a growing stream. Jackson, furious, stopped one soldier and demanded to know why he was falling back. When the soldier replied that he had run out of ammunition, the general shouted, “Then go back and give them the bayonet!” Garnett, closer to the action at the front, gave the order to fall back. “Had I not done so,” he said later, “we would have run imminent risk of being routed by superiority of numbers, which would have resulted probably in the loss of part of our artillery and also endangered our transportation.” At 6:30 pm, he ordered the brigade to withdraw. Fulkerson’s men soon followed suit.

Jackson angrily made his way to the front, where he encountered Garnett shouting at his men to make an orderly retreat. “Why have you not rallied your men?” Jackson demanded. “Halt and rally!” Garnett tried to explain the situation, but Jackson turned away and grabbed a frightened drummer boy by the shoulder. “Beat the rally!” he screamed. “Beat the rally!”

Jackson surveyed the field and felt that it was not time yet to fall back into safer positions. “Though our troops were fighting under great disadvantages,” he said later, “I regret that General Garnett should have given the order to fall back, as otherwise the enemy’s advance would at least have been retarded, and the remaining part of my infantry reserve have had a better opportunity for coming up and taking part in the engagement if the enemy continued to press forward.”

Garnett finally located Colonel William Harman of the 5th Virginia and directed him to place the regiment in a defensive position on the crest of a small hill while the rest of the Confederates withdrew. Thanks in large part to the disarray of the on-charging Union troops and the approaching darkness, Harman’s men, joined by elements of the 42nd Virginia, managed to stabilize the line. As night fell, the infantry fell back behind the screening cavalry and headed south along the Valley Turnpike toward Bartonsville.

The Faulty Intelligence of Colonel Ashby

By 8 pm, the Battle of Kernstown was over. Of the 12,300 men engaged in the struggle, 1,308 were casualties. On the Union side there were 590 casualties, while the Confederates suffered 718 losses, including 263 captured. Among the latter was one of Jackson’s own kinsmen: Lieutenant George G. Junkin, a cousin of the general’s first wife, Ellie. Jackson, dismounting beside a campfire alongside the road, stood looking morosely into the flames. A Southern cavalryman, with ill-advised humor, remarked to the general that “the Yankees don’t seem willing to quit Winchester, sir. It was reported that they were retreating, but I guess they’re retreating after us.” Jackson’s eyes flashed. “I think I may say I am satisfied, sir,” he snapped.

In the cold light of day, Jackson would find himself a good deal less satisfied.

Clearly, Ashby’s faulty report on the enemy strength at Winchester was a major contributing factor in the defeat. Jackson’s major mistake in sending in his reserves during the midpoint of the battle was based in large part on Ashby’s badly underestimated numbers. For his part, Ashby admitted his erroneous intelligence in his official report. “Having followed the enemy in his hasty retreat from Strasburg on Saturday evening,” he wrote, “I came upon the forces remaining in Winchester within a mile of that place and became satisfied that he had but four regiments, and learned that they had orders to march in the direction of Harpers Ferry.”

Although the bad information may have caused Jackson’s defeat, he was initially magnanimous, praising Ashby in his official report of the battle: “During the engagement Colonel Ashby, with a portion of his command, including Chew’s battery, which rendered valuable service, remained on our right, and not only protected our rear in the vicinity of the Valley turnpike, but also served to threaten the enemy’s front and left. Colonel Ashby fully sustained his deservedly high reputation by the able manner in which he discharged the important trust confided to him.” Jackson also praised the ladies of Winchester, who tended to the injured and sick, and the men of Winchester who buried the dead.

General Garnett’s Court Martial

The general was not so accommodating to Garnett. Two weeks after the battle, Jackson relieved Garnett of command and placed him under arrest pending a court-martial for his unauthorized retreat at Kernstown. “I regard Gen. Garnett as so incompetent a brigade commander,” Jackson wrote, “that, instead of building up a brigade, a good one, if turned over to him, would actually deteriorate under his command.”

Garnett, furious and embarrassed, demanded an immediate trial. The five regimental colonels in the Stonewall Brigade rallied to his defense, saying Garnett’s actions had been justified. Jackson’s loyal aide, Sandie Pendleton, noted in a letter home to his mother that “the brigade is in a very loud humor at [Garnett’s arrest] for he was a pleasant man and exceedingly popular.” But Pendleton defended Jackson’s decision, adding, “The arrest, however, was necessary, and I now see why Napoleon considered a blunder worse than a fault. Genl. G’s fault was a blunder.”

In the end, the court-martial was delayed, then adjourned without a verdict. Garnett returned to the army as a brigadier in Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps and was later killed commanding his brigade during Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. Too sick to walk that day, Garnett had ridden a horse directly up to the Union lines before being fatally wounded. Many felt that his actions at Gettysburg were a pointed attempt to regain the reputation he had lost at Kernstown.

A Strategic Victory for Stonewall Jackson

Kernstown remained Stonewall Jackson’s only major tactical defeat during the war. But while the Union succeeded in forcing Jackson’s men off the field and into retreat the following day, Jackson in the end accomplished most of his original objectives, albeit inadvertently. Abraham Lincoln, upon learning of the surprising battle in the Shenandoah, became overly concerned about the potential threat to Washington. He ordered two full divisions from Banks’s corps back into the valley and recalled Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s I Corps to Washington as well, drawing at least 50,000 valuable men away from McClellan’s upcoming Peninsula Campaign. The absence of these men may well have been a determining factor in McClellan’s eventual defeat. In this way, at least, Kernstown could be considered a strategic victory for Jackson and the Confederates, despite the fact they had been driven from the field.

That was the position Jackson took as well. In an after-action report filed during the second week of April, he maintained: “Though Winchester was not recovered, yet the more important object, for the present, that of calling back troops that were leaving the valley, and thus preventing a junction of Banks’ command with other forces was accomplished, in addition to his heavy loss in killed and wounded.” A few days later, Jackson wrote to his wife, Anna: “I am well satisfied with the result. Time has shown that while the field is in possession of the enemy, the most essential fruits of the battle are ours. For this and all our Heavenly Father’s blessings, I wish I could be ten thousand times more thankful.”

Jackson spent the remaining months of spring engaged in his Valley Campaign constantly disrupting Union forces and preventing them from reinforcing McClellan. The Battles of McDowell, Front Royal, First Winchester, Cross Keys, and Port Republic were all victories for Jackson. By the time the Battle of Port Republic was over in early June 1862, Jackson was able to join General Robert E. Lee for the Seven Days’ Battles, where Lee successfully defeated McClellan and forced him to retreat back to the Virginia Peninsula, thus ending the Peninsula Campaign. As one modern historian has noted: “Had Jackson won the Battle of Kernstown, he could scarcely have achieved a more favorable result. History can provide few examples of a defeat that so favored the defeated. Jackson’s lucky star had begun its ascendancy.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments