The peripatetic Archibald Forbes had made his reputation as a war correspondent during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, when he bet rightly on the Prussians to win the war and attached himself accordingly to King Wilhelm I’s field headquarters. Strange as it now seems, given the horrifying sweep of European military history in the next 75 years, most observers at the time believed that the French, under Napoleon III, would easily win the war.

The Scottish-born Forbes, the son of an Aberdeen minister, had resigned from the Royal Dragoons after five years of service; he found the other side of the cannon’s mouth a good deal more congenial. During his first war, Forbes demonstrated a valuable knack for being in the right place at the right time. He was standing around a French barn with King Wilhelm and Chancellor Otto von Bismarck when they received news of the great Prussian victory at Gravelotte, and a few weeks later he was the only English-speaking correspondent to personally witness Napoleon’s surrender to Bismarck in a little weaver’s cottage following the French debacle at Sedan.

Shortly thereafter, Forbes adroitly switched locations, if not sides, sneaking into Paris to cover the rise of the Paris Commune and its swift decline, writing a remarkably graphic account of a communard’s death at the hands of his reactionary fellow citizens. Forbes, being a true English gentleman, had tried to rescue the man from the ravening crowd, only to have the victim’s brains splash cinematically onto his boots.

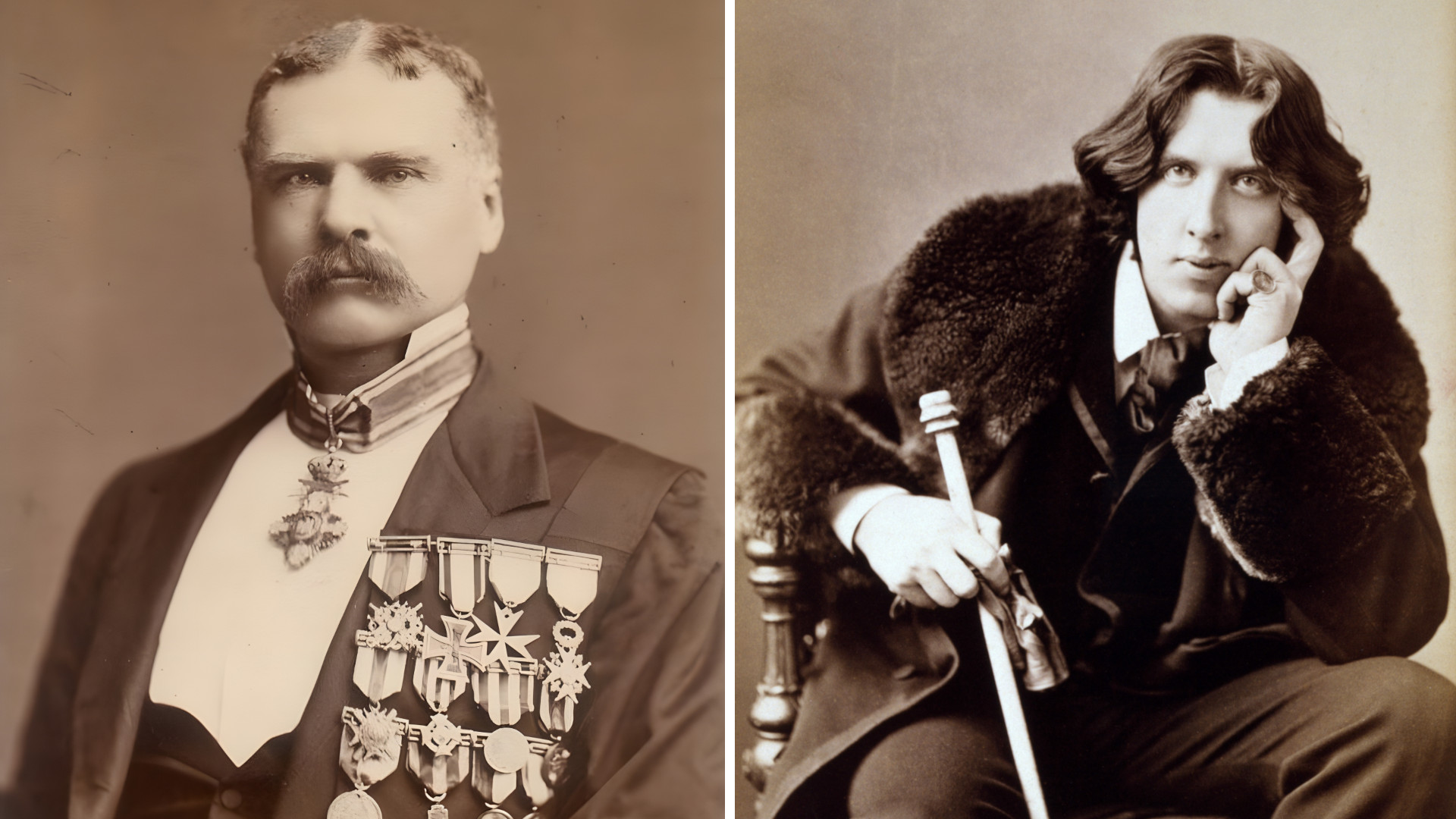

More splendid little wars followed. Forbes got another worldwide scoop during the Russian-Turkish War of 1877, when he rode non-stop for three days and nights across the Russian steppes to personally deliver to Czar Alexander II the glad tidings of a Russian victory at Shipka Pass. The czar was so delighted with the news that he bestowed on Forbes the Order of St. Stanislas, which found its place on Forbes’s chest alongside the Iron Cross, Second Class, for Noncombatants; the Pour le Merite, Civil Class; and the French Legion of Honor.

Forbes made another famous news-bearing ride two years later during the nasty British war with the Zulus that brought the empire a horrific massacre of troops at Isandhlwana. Fortunately for Forbes, he was not there that day, or he wouldn’t have lived to write about it. After the ensuing Battle of Ulundi, he dashed through Zulu territory to bring news of the British victory there. The British commander, Lord Chelmsford, proving to be more of a stickler for military protocol than continental Europeans, refused Forbes’s application for a Victoria Cross, noting that Forbes had also been carrying personal messages at the time. In Chelmsford’s way of thinking, that made the correspondent more a mailman than a hero.

Forbes capitalized on his fame as by becoming a traveling lecturer for famed theatrical producer Richard D’Oyly Carte. During one memorable tour in America in 1882, he crossed swords—almost literally—with fellow lecturer Oscar Wilde. Forbes and Wilde could not abide one another, and after Forbes made a (perhaps) joking comment about the commercial possibilities of the Aesthetic Movement, which Wilde was championing on his tour, a war of words erupted between the two flamboyant performers.

It took the personal intercession of a mutual friend to end the battle. That did the trick, at least publicly, and Forbes quit threatening to brain Wilde on sight. Behind the scenes, however, the old jingo continued to hold a grudge, repeating the false if entirely plausible rumor that American showman P.T. Barnum had offered Wilde 200 pounds to ride Jumbo the Elephant down Broadway with a sunflower and lily clutched in either hand. How Wilde was supposed to hold onto the elephant Forbes neglected to explain—making it one of the few times in his life that he was short of words.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments