By Eric Niderost

Shortly after midnight on the morning of Monday, August 18, 1862, an uneasy group of Santee Sioux warriors arrived at the simple frame home of Taoyateduta, known to the whites as Little Crow. The day before, four Santee warriors had killed five white people, including two women, while hunting near Acton, Minnesota, 40 miles north of the Lower Sioux Agency on the Minnesota River. They might not have known it at the time, but the incident sparked the Dakota War of 1862.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, a council of elders decided to seek the chief’s advice. Little Crow was asleep on the ground floor of his house when they arrived, but he quickly rose and came outside to confront the assembled crowd of 100 chiefs and warriors.

For years, Little Crow had been the principal spokesman and negotiator for his people, but recently he had been accused of becoming a pliant tool of the whites, counseling peace and acquiescence to the ceaseless demands for more Indian land. As tensions mounted, the Mdewakanton—his branch of the Santee Sioux—showed their anger by removing Little Crow from his speakership. This was a serious blow to his honor and prestige, and Little Crow took the demotion bitterly. Now it seemed as though he was needed again. His prestige, however tarnished, would be an asset in an all-out war with the whites, which many now feared was coming soon. (Read more about the fighting and conflicts in the American West by subscribing to Military Heritage magazine.)

“Taoyateduta is a Coward”

The Sioux knew that there were few white soldiers left in Minnesota, most regulars having been withdrawn to fight the Confederates in the Civil War. One strong push, some said, and the whites would be expelled from the Minnesota Valley forever. Little Crow knew better. He had traveled east to Washington D.C., a few years earlier and had seen with his own eyes how numerous white people were. Indian grievances, however just, would not be remedied by war, and might well lead to his people’s extinction. “The white men are like locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm,” he warned his visitors. “You may kill one, two ten, yes, as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them. Kill one, two ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you. Count your fingers all day long and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count.”

One or two of his listeners whispered the fatal phrase: “Taoyateduta is a coward.” No Indian could stand being called a coward, and Little Crow saw that this was his last chance to reclaim his honor and prestige. If he refused to go to war, his reputation would sink even lower. Against his better judgment, the chief decided to fight. “You will die like rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the Hard Moon,” he warned, but added: “Taoyateduta is not a coward. He will die with you.” With that simple statement, the Dakota War of 1862 began.

Financial Pressures on the Sioux

The origins of the uprising could be traced to a series of ill-advised treaties the Indians had signed in the 1850s. The first pacts were signed at Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851. Collectively, the Sioux ceded almost 24 million acres of prime agricultural land, which was legally opened to white settlers three years later. The tribe agreed to part with the priceless territory in exchange for comparatively insubstantial amounts of cash and annuities. The treaties left the Sioux—some 7,000 strong—on two reservations, each 20 miles wide and 70 miles long, hugging the Minnesota River. As was customary, the federal government established administrative agencies on each reservation. The Upper Sioux Reservation was served by the Yellow Medicine Agency, while the Lower Sioux Reservation had the Redwood Agency. White merchants established stores at both agencies where the Sioux could spend their annuity money or trade furs for food and other goods.

By 1857, white settlers, rapacious as ever for new land, started to pressure the government to open the Dakota Territory for settlement. In the spring of 1858, a Sioux delegation led by Little Crow and Indian agent Joseph R. Brown traveled to Washington to negotiate a new series of treaties. The treaties of 1858 further reduced the Santee reservations, ceding the strip that was north of the Minnesota River for an amount to be determined by the U.S. Senate. It would take two more years for the senators to decide on payment, a laughable 30 cents per acre—well below the going rate for prime real estate. Meanwhile, almost a million additional acres of Sioux homeland were lost at the stroke of a pen. Returning home, Little Crow was hard put to cast the treaty in a favorable light.

White traders were the greatest source of conflict and controversy in the years leading up to the 1862 uprising. As early as 1851, traders had laid claim to a substantial portion of the Indian annuities. For the 1851 pact, the figure was approximately $400,000. Traders also insisted that they be given the annuity money directly. In theory, they would then subtract what the Indians owed them and distribute what was left. In practice, many unscrupulous traders presented fraudulent claims that left little, if any, cash for the Sioux. Intratribal friction rose between those who sought to take on white ways, called “cut hairs,” and those who clung to traditional tribal beliefs, called “blanket Indians.”

The novel specter of financial debt haunted the free-living Sioux, many of whom found themselves owing huge sums of money for blankets and food. It was a vicious cycle, especially when wild game became scarce. The Santees in the north became increasingly dependent on white men for food and other goods. The traders’ greed was doubly resented, since virtually all of them had married Indian women. Social relationships and kinship were the cornerstones of Indian society. In the Santees’ eyes, the traders should have had the decency to simply wait patiently until their customers, who were often their relatives, were able to pay their bills.

A delay in annuity payments caused by the worsening war between the Union and the Confederacy sparked the Dakota War of 1862. Hungry tribesmen, desperate for food, broke into a government agency storehouse at Upper Agency to take flour and other items. Indian agent Thomas Galbraith was reluctant to depart from the norm—distributing food only after the annuity money arrived—and the white traders adamantly refused to extend credit. Army Lieutenant Timothy J. Sheehan, commanding the 5th Minnesota Regiment, had his men train a loaded howitzer on the angry crowd.

“When Men are Hungry, They Help Themselves”

Little Crow and other Indian leaders at the Lower Agency convened a council to discuss the crisis. Among those present were Little Crow, Galbraith, and several white traders. John P. Williamson, a missionary, handled the translating chores. Little Crow asked that the Indians be given the food that was rightfully theirs. They were starving, he warned, adding, “When men are hungry, they help themselves.” Andrew J. Myrick, one of the leading traders, discounted the warning. “So far as I am concerned,” he said, “if they are hungry they can eat grass.” After Williamson translated Myrick’s words into Dakota Sioux, the assembled Indians reacted with angry war whoops and threatening gestures. Myrick’s stubborn insensitivity was glossed over when Sheehan convinced Galbraith to distribute some pork and flour to the starving Indians.

That same day, four young Santees were passing the Robinson Jones homestead in Acton, three miles southwest of Grove City. They knew Jones, who ran a combination post office, inn, and store. The Indians went up to the house and demanded whiskey, becoming angry when Jones refused. One thing led to another, and the Indians killed Jones, his wife, and neighbors Viranus Webster and Howard Baker. Fifteen-year-old Clara Wilson, whom Jones had adopted, was also shot and killed. Once their fury had abated, the four warriors realized that they were in serious trouble. They returned to their village, explaining what had happened and urging an all-out war to drive the whites from the Minnesota River Valley. The late-night meeting with Little Crow followed.

Massacre at Redwood Post

Once he had decided on war, Little Crow directed that the Lower Sioux Agency’s Redwood post be attacked at dawn. The agency post was a small cluster of log cabins, frame houses, and brick buildings perched atop a bluff. Some 60 white men and women lived there, including cooks, clerks, teachers, missionaries, and government laborers who tilled the fields. The traders’ stores were located a quarter of a mile from the government buildings.

The merchants, clerks, and others had just sat down for breakfast when a large party of Indians arrived, ominously painted for battle. Before the whites could react, or even fully comprehend, the meaning of the war paint, the Indians began killing them. Dakota warriors broke into small groups, shooting down all they encountered. Taken by surprise, the victims were probably unaware of why they were being murdered. Myrick’s store was a special target. One warrior was heard to mutter, “Now I will kill the dog who wouldn’t give me credit.”

Myrick’s clerk and cook were shot down, but at first the merchant himself could not be found. He was discovered trying to flee from a second-story window in his store and shot down without mercy. It was said Myrick had fathered three children by a Sioux woman, then abandoned her for a younger woman. The jilted woman’s brother was the first to pump a bullet into the businessman’s body. As was customary in Sioux culture, Myrick’s body suffered post-mortem indignities. Arrows were shot in his corpse and an old scythe driven through his rib cage. Remembering his insulting words, warriors stuffed Myrick’s mouth with grass. “Now Myrick eats grass himself,” one warrior exalted.

The general massacre slowed when the Indians began to loot the buildings, then put them to the torch. The distraction allowed many settlers time to escape. Not all the Indians joined in the general bloodlust. Several slipped away and warned white friends and relatives, giving them enough time to escape. The fugitives made their way to the Redwood Ferry in an attempt to cross the Minnesota River and comparative safety. Ferryman Humbert Miller heroically stayed at his post, shuttling dozens of people over to the far bank before the Sioux finally killed him.

News Reaches Fort Ridgely

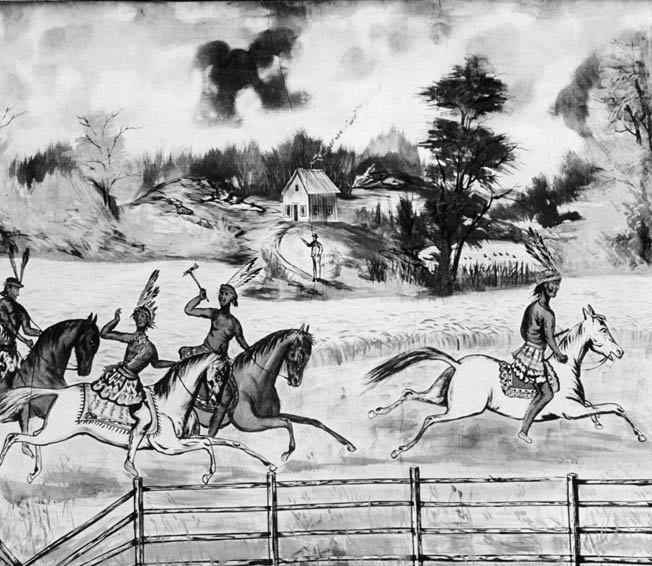

Warriors fanned out, spreading terror and death through the surrounding countryside. From August 18 to August 21, many white homesteads were wiped out. The Beaver Creek settlement, just across the Minnesota River from Redwood and Milford Township, was particularly hated, since the Sioux felt that the whites living there were squatting on stolen Indian land. In Milford alone, 50 or so whites, mostly unarmed German immigrants, were felled by bullets or chopped down by hatchets.

Most of the civilian refugees made for Fort Ridgely, situated on a spur of high prairie ground 150 feet above the Minnesota Valley floor. The site was commanding but flawed. Deep ravines to the east, north, and southwest provided ample cover for potential attackers. The post itself was unfortified, merely a hodgepodge of barracks, stables, commissary, and other military buildings. Like many forts of the period, Fort Ridgely did not have a stockade wall like the ones often depicted in Westerns.

The main buildings were a two-story stone barracks, a one-story commissary, officer’s quarters, and a combination headquarters and surgeon’s facility, all grouped around a parade ground 90 yards wide. Behind the barracks were some log houses and the post hospital. To the south was a large stable just across the road from New Ulm. The ammunition magazines were exposed, lying some 200 yards northwest of the fort.

Refugees began streaming into Fort Ridgely not long after the first attacks on the Lower Agency. Post commander Captain John S. Marsh was incredulous at first, scarcely believing that such a major uprising could be taking place under his very nose. But when the reports became too numerous to ignore, Marsh took action. Drummer boy Charles Culver beat a steady tattoo, and 76 soldiers fell into line. Lieutenant Sheehan had left for Fort Ripley, located on the Mississippi River, the day before. A messenger was quickly dispatched urging Sheehan to return immediately. “The Indians are raising hell in the Lower Agency,” Marsh’s missive explained.

Reinforcing Ridgely

Marsh took 46 soldiers and headed for the scene of the fighting at the Lower Agency. Nineteen-year-old Lieutenant Thomas B. Gere was left in command of the post. Gere, a “shavetail,” or greenhorn, had only been in the Army for eight months. To make matters worse, he was also ill, having contracted mumps a short time earlier. There were 29 men left to defend the post. In the meantime, Marsh continued on toward Lower Agency. Marsh and interpreter Peter Quinn rode mules, while the soldiers were riding in wagons. They began to encounter refugees going in the opposite direction, all with the same tale of surprise, mayhem, and abject terror.

At Redwood Ferry, Marsh and his men were ambushed by Chief White Dog, a sub-chief who was normally known to be friendly to whites. Attacked on three sides, the soldiers made their way through thick vegetation along the river bank. Marsh, attempting to swim across the river, was seized by a cramp and drowned. The surviving soldiers—half the original force—extricated themselves with difficulty and returned to Fort Ridgely. The ambush was the Indians’ first major victory, and their elation knew no bounds. One warrior boasted, “The white men can be killed like sheep!” Little Crow, who knew what they were up against, cautioned against overconfidence, but he was overruled by young hotheads who were openly contemptuous of the whites’ fighting abilities.

Little Crow wanted to attack Fort Ridgley the next morning, but several days passed before he could muster enough warriors to mount a credible assault. By then, Fort Ridgely’s most vulnerable time had passed, although the Indians did not yet know it. Sheehan had arrived at the fort after a grueling all-night march of 40 miles. He took over command from Gere and continued to prepare for the defense. Indian agent Galbraith, who had been at St. Peter, arrived at the fort with 50 members of the Renville Rangers, a mixed-blood militia unit originally recruited to fight Confederates. Including 20 or so male refugees, Sheehan now had around 180 effectives inside the fort. He sent urgent word to Minnesota governor Alexander Ramsey for more reinforcements, and Ramsey commissioned former governor Henry Hastings Sibley to lead relief troops from Fort Snelling to Fort Ridgely.

It would take time for Sibley to arrive. In the meantime, the defenders would have to fend for themselves. Breastworks were thrown together to connect the innermost buildings. Barrels of flour, salt pork and beef went into the barricades, the gaps filled in by odd pieces of cordwood. The post had four artillery pieces that had been left behind when the Regular Army troops had been withdrawn for Civil War service. In a stroke of luck, Sergeants James G. McGrew and John Jones, both skilled artillerists, had remained behind. Hastily, they trained infantry soldiers and civilians to work as effective gun crews. One 12-pounder mountain howitzer was placed in the gap between the two-story barracks and the bake house. Another howitzer was wheeled out to the northwest corner.

Driven Back by “Rotten Balls”

The Indians finally attacked on the morning of August 20. Little Crow led a diversionary attack on the west side of the post. While the defenders’ attention was fixed on Little Crow, Chiefs Mankato, Gray Bird, Shakopee, and others led an assault on the northern perimeter They managed to seize several outbuildings, and for a time it looked as if the Sioux might win. The fighting grew heavier, with the defenders’ Springfield rifle-muskets unleashing sheets of smoke and flame with each volley. Then the artillery opened up, iron monsters the natives had never seen before—at least not in action.

The warriors were particularly upset by the howitzer shells, which they called “rotten balls.” When they exploded, they sent up a lethal spray of hot metal in every direction, killing and maiming with horrifying ease. The Indians rushed the western corner of the fort, but were stopped cold when Jones and his 6-pounder crew shot their gun off at point-blank range. It was too much for flesh and blood to stand. The warriors withdrew, carrying off their dead and wounded. A thunderstorm moved in that night, soaking the ground and washing away the stains of carnage.

On August 22 the Sioux massed for a final, all-out assault on the beleaguered post. Little Crow, who had been slightly grazed by a cannonball the day before, rode to battle in style, seated in a handsome horse-drawn buggy driven by a mixed-blood named David. Some 800 Indians gathered for the effort, including many warriors who had newly joined the uprising. The Sioux sneaked close to the fort, using the tall grass for cover and camouflaging themselves with prairie grass and flowers in their headbands. They rushed several buildings, gaining a foothold in the stables and the sutler’s house. Well aimed artillery shells soon set the stables alight, the flames and smoke forcing the Indians to abandon their newly won prize. The sutler’s house was soon engulfed in flames as well.

The Indians literally tried to fight fire with fire by launching a hail of flaming arrows on building roofs, but the shingles were still damp from the previous night’s rains and failed to ignite. One or two roofs did finally catch fire, but were quickly extinguished with buckets of water. Frustrated, the Sioux launched another all-out attack on the southwest corner. It was the same story—case shot and shells broke up the attempt, leaving the natives little to show for their courage.

The Sioux withdrew, this time for good. Chief Big Eagle said later: “We thought the fort was the door to the valley as far as St. Paul, and if we got through nothing could stop us. But the defenders of the fort were very brave, and kept the door shut.” Sibley’s relief force of some 1,400 men arrived at Fort Ridgely a few days later.

Raid on New Ulm

Now the Indians’ wrath fell upon New Ulm, a community of some 900 souls and the largest white settlement near the Sioux reservation. Many of New Ulm’s men were gone, having joined the Union Army to fight the South. The town’s vulnerability made it a tempting target, full of goods—and pretty young women—that could be carried off as booty. New Ulm was built on two natural terraces of land like two giant steps that rose up from the Minnesota River Valley to the height of about 200 feet and ended in a high bluff in back of the town. The community, which was founded by Germans, boasted a fine hotel called the Dacotah House.

On August 18, a recruiting party of New Ulm men had left town to gather volunteers for the Union Army from the scattered farm homesteads in the area. Sioux warriors ambushed them at Milford Township, killing 11 and causing the survivors to fall back to New Ulm. The citizens were thrown into a near-panic by the evil tidings. There were few able-bodied men in town, perhaps 40 individuals, and even fewer arms and ammunition. Some defenders were forced to arm themselves with pitchforks and other farm implements—little use against an enemy armed with up-to-date rifles. Brown County Sheriff Charles Roos and local citizen Jacob Nix organized the defense.

Minnesota Street, the town’s principal thoroughfare, was barricaded for three blocks from Center to Third North. New Ulm’s brick buildings made good defensive positions because of their relative resistance to fire. Couriers were dispatched to neighboring towns asking for immediate help. The citizens of St. Peter, Le Sueur, and other settlements responded with alacrity, but it would be some time before reinforcements arrived. In the meantime, New Ulm had to weather its first Indian assault alone. About 3 pm on Tuesday, August 19, a force of 100 warriors dismounted and began firing into the town. Six townsfolk were killed, including a 13-year-old girl named Emilie Pauli, and five others were wounded.

The sky turned overcast, signaling the beginning of a large thunderstorm. Jagged streaks of lighting sliced through the sky, accompanied by torrential downpours of rain. The rainstorm seemed to dampen the Indians’ ardor. The citizens welcomed the reprieve, but the danger was not over. Beginning about 9 pm, much-needed reinforcements rode into town. Judge Charles E. Flandrau headed some 125 armed militiamen, a welcome addition to the defense. Other militia units also came in, many of then sporting bellicose names like the Le Sueur Tigers and the Winnebago Guards. Flandrau took overall command of the town’s 300 able-bodied defenders. After this, it was simply a matter of watching and waiting. More refugees had come to New Ulm, swelling the town’s numbers to perhaps 1,500 people.

190 Buildings Destroyed

On Saturday morning, August 23, New Ulm scouts spotted pillars of smoke rising into the sky in the direction of Fort Ridgely. If the fort had fallen, the Sioux might attack New Ulm from the north side of the Minnesota River. To guard against this possibility, Flandrau sent William Harvey and 75 men to investigate. It was a ruse, and Flandrau had risen to the bait. Harvey and his men were soon cut off and forced to retreat to St. Peter. Harvey’s departure left New Ulm with around 200 defenders, not all of them well-armed.

At about 9:30 am, the Indians finally showed themselves, coming out of the woods to assemble on the prairie just west of New Ulm. The 600 to 800 warriors were led by Mankato, Wabasha, and Big Eagle, chiefs of considerable experience and skill. Flandreau ordered his second in command, militia captain William B. Dodd, to take his men and meet the Indians beyond the barricades. It was a near-fatal error. The Sioux began fanning out until they covered the defenders’ entire front. The Indians, wearing breechcloths, arm bands, and feathered headdresses, picked up the pace. The advance culminated with the Indians sweeping down on the defenders with a cry so bloodcurdling that it unnerved the defenders, who broke and ran for the safety of the barricades and nearby houses. The Indians pressed forward and managed to occupy several dwellings before the townsfolk rallied and stopped the attack.

Flandrau later recalled that “the firing from both sides became general, sharp, and rapid. It got to be a regular Indian skirmish, in which every man did his own work after his own fashion.” About 20 men from the Le Sueur Tigers took shelter in a local windmill three blocks from the business district and made it a major stronghold. The Frederick Forester Building, a combination pottery works, post office, and private home, located outside the barricaded perimeter, was another major strongpoint.

The town’s lower terrace, near the river, was buffeted by high winds, which the Indians tried to use in their favor. They put many buildings to the torch, the thick black coils joining together to form a perfect cover for their advance. Sixty warriors, some on horse, others on foot, made their way through the acrid stench of burning wood. The fighting reached a climax around the blacksmith shop of August Kiesling, which the Indians had occupied early in the attack. When Flandrau realized the Sioux were advancing behind the smokescreen, he gathered some men to leave the relative safety of the barricades and meet the enemy head on. This time the tables were turned, and the whites’ fierce battle cry unnerved the Indians. Getting a taste of their own medicine, the Sioux warriors halted, wavered, then withdrew. The Indians also evacuated the blacksmith shop, a major thorn in the defenders’ side.

Before withdrawing into the barricades, Flandrau torched the remaining buildings in the lower parts of town. Soon, crackling flames devoured the houses and belongings of German settlers who had come to America with such hope. Once the houses and other buildings were consumed, the Indians could find little cover in the blackened ruins. There was little left of New Ulm; around 190 buildings were destroyed.

The Sioux finally broke off the attack, leaving the exhausted defenders with their lives, but little else. On Monday, August 25, it was decided to evacuate what remained of New Ulm. There was little food, and ammunitions stocks were perilously low. The smell of burnt wood hovered over the town like the remains of a funeral pyre, to which was added the sickening stench of unburied corpses decaying in the summer heat. Fear of pestilence decided the issue, and a melancholy caravan of 153 wagons, packed with women, children, and wounded men, painfully made its way to Mankato, 34 miles distant.

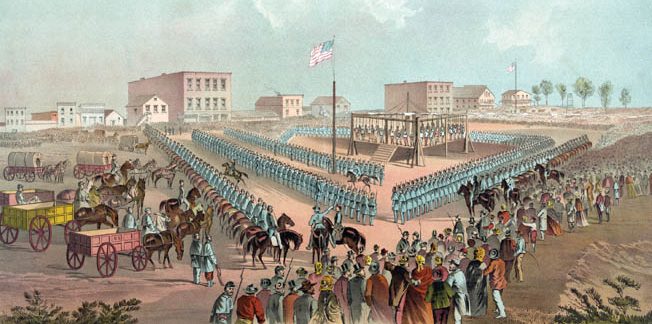

The Largest Mass Execution in American History

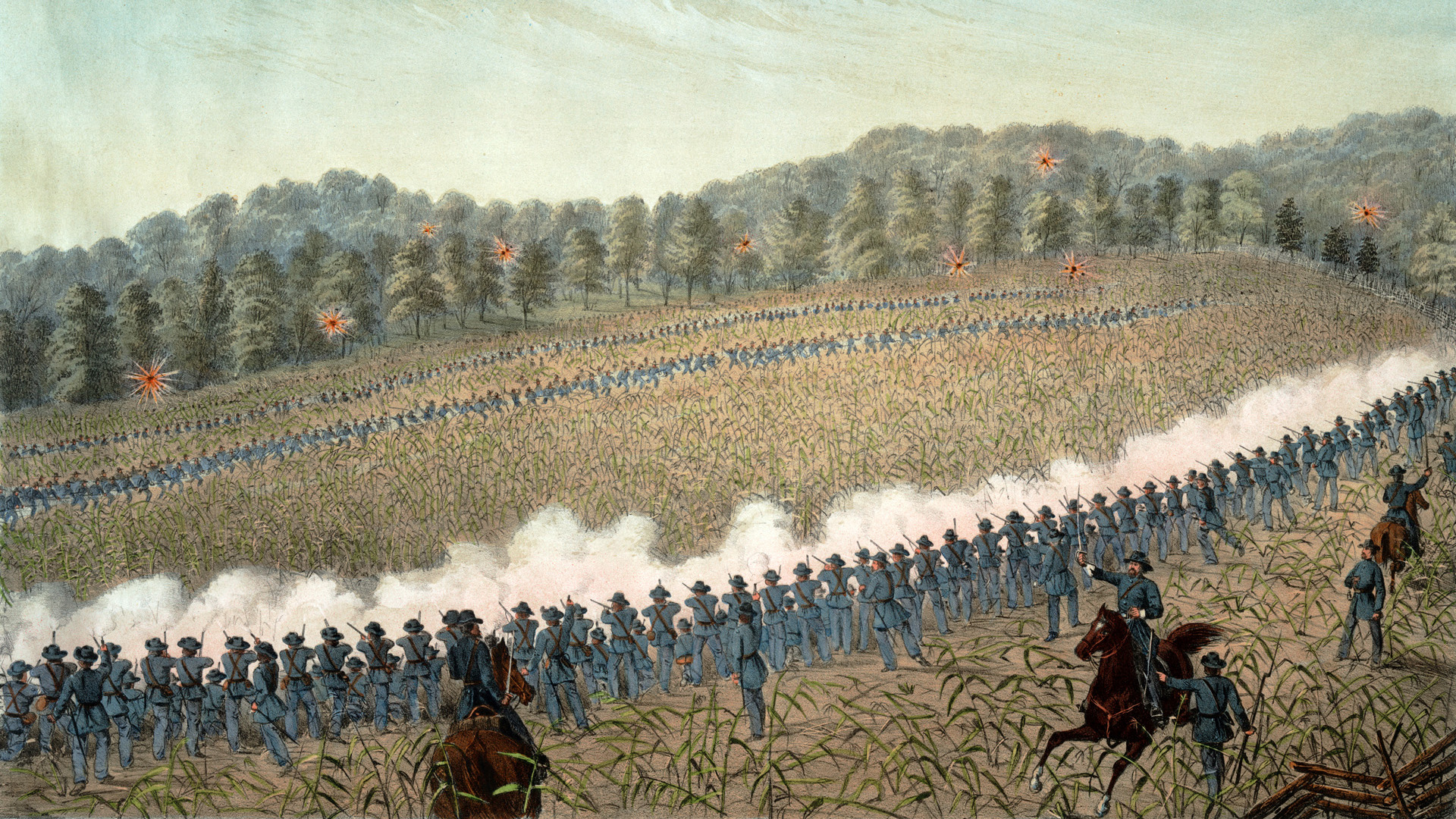

Although there was more fighting in the weeks to come, the clashes at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm ultimately decided the Dakota War of 1862. Increasingly divided and poorly led, the Sioux were planning a last large attack on Sibley’s relief force, camped near Wood Lake, on September 23. Discovered by chance when soldiers of the 3rd Minnesota Regiment, newly paroled from Civil War battlefields, left camp without orders to pick potatoes in nearby fields, the Indians attacked in piecemeal fashion, only to be driven back into a ravine. Cannon fire swept the hollow, killing Chief Mankato and breaking the back of the Sioux resistance. Most surrendered, at the same time releasing 267 prisoners, including 162 mixed bloods and 107 whites, almost all of them women and children. In all, more than 800 white settlers had died in the uprising.

Little Crow fled to Canada, and 303 Sioux warriors were tried and sentenced to death for war crimes and atrocities. The trials were a travesty of justice, given the cultural differences, the defendants’ lack of understanding, and the whites’ thirst for revenge. Some trials lasted only five minutes. President Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer himself, intervened, reviewing each case personally. After careful deliberation, only those who had raped or murdered were condemned to death. Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 defendants, allowing the execution of 39 prisoners. Last-minute evidence gave a reprieve to one of the condemned; the rest were hanged on December 26, 1862. It was the largest mass execution in American history.

Little Crow drifted back to the United States and was killed a few months later while picking berries in a farmer’s field. The settler, a man named Nathan Lamson, didn’t even know at first that he had killed the infamous Little Crow. When the chief’s body was taken into town, it was recognized, and the chief’s remains were dragged through the street and thrown ingloriously onto a garbage heap. More than a century later, in 1971, in a gesture of reconciliation, the Minnesota Historical Society released Little Crow’s bones to his descendants. He was buried with honor in a small ceremony attended only by family members.

Join The Conversation

Comments