By Robert F. Dorr

In the closing months of World War II, Staff Sergeant Henry E. “Red” Erwin, Sr., picked up a burning phosphorus flare inside the cramped fuselage of his Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber high over Japan.

Erwin had a quick, fleeting chance to save the lives of his fellow crewmembers by risking severe, probably fatal, burns to his body. It was the moment of truth for a self-deprecating enlisted airman who spoke of himself in modest, aw-shucks style long after his countrymen gave him the Medal of Honor.

Red Erwin came to the war zone as one of thousands of B-29 crewmembers placed in the North Pacific, on the Marianas islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian for the purpose of attacking Japan. The American taxpayer had equipped them with the largest and costliest aircraft of the war, the first large combat plane to be pressurized, enabling the crew to dispense with heated clothing and oxygen masks and to work in shirtsleeves.

The B-29 was nothing less than a technical miracle, pulled through the sky by four 2,200-horsepower Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone 18, twin-row, turbocharged radial engines. A fully loaded B-29 had a wingspan of 141 feet, 3 inches, weighed 133,500 pounds, and carried a crew of 11 men.

“It was big, heavy, and fast,” said Erwin. “It had beautiful, unbroken nose contours. For practical purposes it was divided into two halves, with part of the crew forward of the bomb bay, the other part aft, connected by a crawl tunnel above the bay. As the radio operator, I sat with my back to the bulkhead in the rear of the front half, looking forward at the flight engineer, the two pilots and, in the very front, the bombardier, who had the best view in the house.”

Erwin’s unit was the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Wing, and Erwin’s B-29 was one of the few planes in Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay’s XXI Bomber Command to have two names. The B-29, serial number 42-65302, was called Snatch Blatch and The City of Los Angeles. The first name, sinister as the night in which the B-29 often operated, came from a black witch in the writings of French Renaissance satirist François Rabelais.

The airplane commander and pilot was steady, calm, mild-mannered Captain George A. “Tony” Simeral. This was a seasoned crew, formed at Dalhart, Texas, in June 1944, and deployed overseas in January 1945.

“We were regular guys,” said Erwin. “We took pride in how we functioned as a crew.” And their talents were recognized.

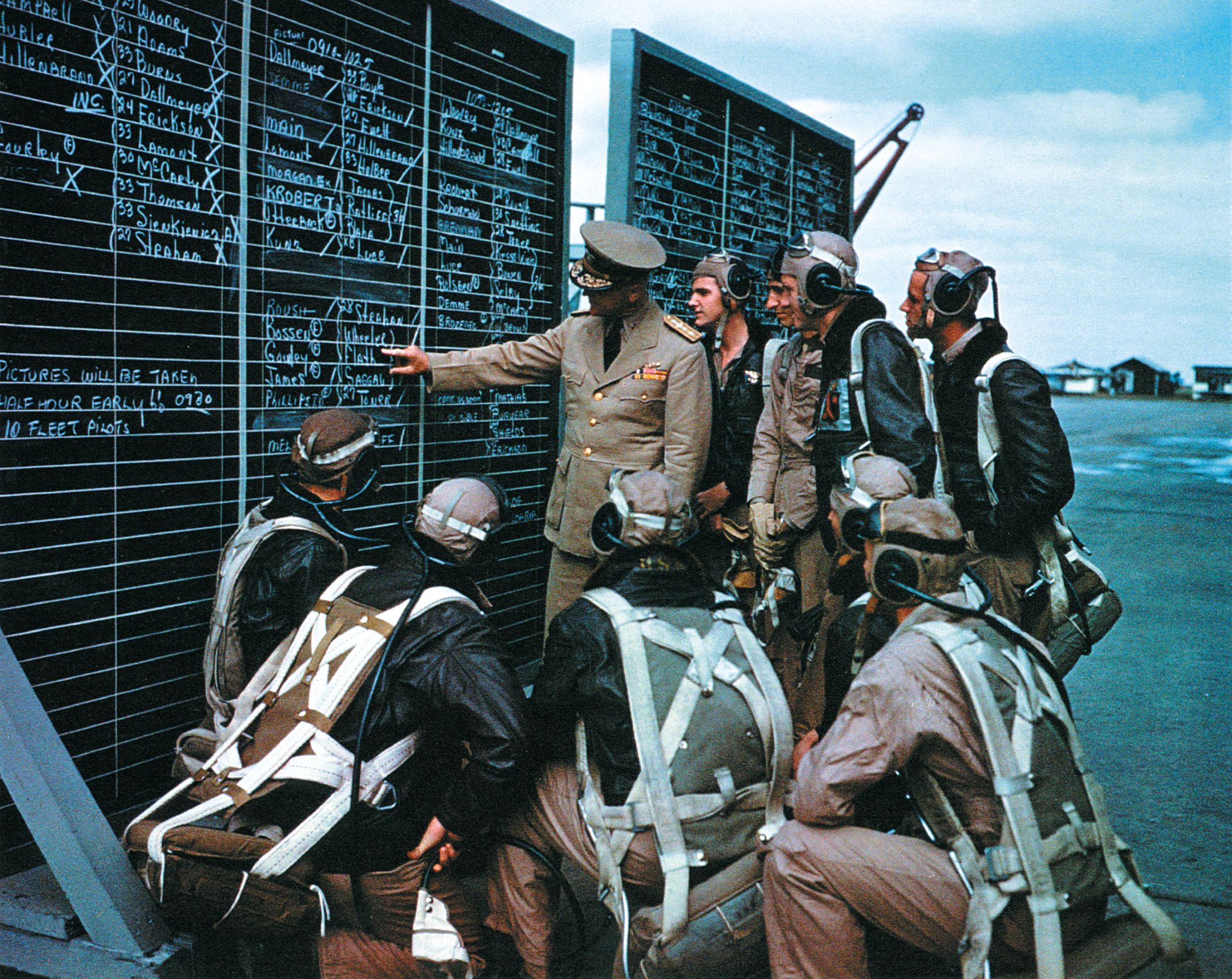

Firebombing Tokyo with General Power

Looking for a way to improve bombing results, LeMay decided to abandon high altitude, daylight precision attacks with explosive bombs. Army Air Forces boss General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold instructed LeMay to make plans to attack Japanese cities at low level at night using incendiary bombs. The target for the first and largest firebomb mission would be the Japanese capital.

The Snatch Blatch crew with Simeral in charge and Erwin on radios was selected to carry the on-scene commander.

The plan was to have LeMay aboard, but LeMay had just received a briefing on a new, secret weapon being developed by American scientists in New Mexico. Having already racked up a record for bravery—he had received the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest award for valor, for an action in Europe—LeMay, with his knowledge of the war’s greatest secret, was no longer permitted to fly over enemy territory. The on-scene commander became Brig. Gen. Thomas “Tommy” Power.

In the early morning hours of March 10, 1945, some 330 B-29 bombers arrived over Tokyo and disgorged their cargos of napalm and thermite. It was the most destructive bombing event in history, before or since, and ignited the hottest fires ever to burn on the earth. [See the author’s article in WWII Quarterly, Summer 2014.] Estimates vary, but the mission may have killed as many as 120,000 people. The fire bombs transformed 16 square miles of Tokyo into a smoldering desert.

Erwin peered ahead from his radio operator’s position and watched Power and Simeral interacting. Erwin recalled that in many ways Power was the gruff, brusque, abrupt personality LeMay was perceived as being while LeMay himself was more complicated. Japanese antiaircraft defenses were unprepared for the low-level assault, but the men in the B-29s didn’t know that.

“Power wasn’t content to fly over the target just once,” Erwin recalled. “He wanted to go over Tokyo a second time, and a third, to see how it was going.” Erwin stopped short of calling this behavior risky, let alone foolhardy, but some of the men aboard Simeral’s B-29 were very nervous.

A Dangerous 11th Combat Mission

It was a month later—on April 12, 1945—when Red Erwin faced his greatest challenge. Many Americans remember this as the date Franklin D. Roosevelt died and Harry S. Truman became president. But Erwin’s ordeal and moment of heroism took place on the far side of the International Date Line, over Japan, when it was still a day earlier in Washington.

The target that morning was a chemical plant situated in rough mountains near Koriyama, some 110 miles north of Tokyo. It was the most distant target yet to be attacked by Superfortresses based in the Marianas. It was a complex cluster of small factories, and the attack on its center would require riskier formation flying than usual. Snatch Blatch was the lead aircraft.

Simeral taxied the B-29 out of its revetment and guided the lumbering airplane toward its takeoff point. The plane, looking like an aluminum cigar with wings and bristling with remote-control guns, handled easily and rolled smoothly.

Simeral and co-pilot 2nd Lt. Leroy C. Stabler went through their checklists, put the R-3350s up to full power, and were delighted that the engines, which were sometimes trouble prone, performed smoothly. The noise level inside the aircraft made it impossible to speak except via interphone.

Strapped into his usual radio operator’s seat was Henry Erwin, a modest farm boy born in May 1921, in Adamsville, Alabama, and known to his family as Gene, although crewmates called him Red. As usual, Erwin was willing not merely to handle communications but to take on extra tasks. He was expected to drop phosphorus flares to notify the bomber formation that the lead aircraft had reached the assembly point for the bomb run. This was Erwin’s 11th combat mission.

Occupational Hazards of the B-29

Earlier that week, Erwin had witnessed a loud and fiery crash in which another B-29, limping home on two engines, had overshot its runway and was blown to bits among the coral and coconut palms. Nine men had been consumed by fire, but none of Erwin’s crewmates had been able to elicit a single comment about the incident from the young sergeant.

As Snatch Blatch droned across the water, Erwin made his final radio checks. The airwaves were filled with too much unnecessary chatter, including weather information and formation instructions. Erwin made his last call, kept his earphones on to stay connected to the interphone, and reached for a phosphorus flare.

Approaching the Japanese coast, Erwin prepared to drop the flare through the chute in the forward section of the B-29. This was another low-level mission, and Erwin was in shirtsleeves, minus helmet or cap. When Simeral cued him, Erwin pulled the pin on the pyrotechnic and positioned it in the chute.

Some crewmembers feared the flare chute was too close to the bomb bay. Snatch Blatch was carrying more than three tons of incendiary bombs in its main bay on this day, and more than one crewman had pointed out what would happen if the phosphorus device should explode too close to the incendiaries. The resulting blast would be so sudden that they might not live long enough to know that it happened, and it might even obliterate a four-plane formation of B-29s.

A Defective Fuse

Erwin was ready with the flare when he saw a blur through his side port. “Fighters!” he said.

A yellow, twin-engined Japanese fighter known as a Nick was descending off to their right. Meatball red circles were painted on its wings, and muzzle flashes appeared at its nose.

“I got ‘em,” said top turret gunner Sergeant Howard Stubstad. “There’s also four Zekes circling off to the left.”

“We’re at the assembly point—“ Erwin stammered.

“Four of them!” A voice garbled out the others. “Four Zekes closing on our left!”

As expected, Erwin released his hold on the flare to allow it to drop through the chute. But the signal bomb clattered inside the release pipe and refused to fall through the gate at the bottom of the tube.

It bounced back into Erwin’s face and exploded.

A defective fuse had ignited the flare prematurely. Upon contacting oxygen, the phosphorus lit up to its temperature of 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit.

Fire swirled around Erwin’s head. The blazing device careened around the inside of the B-29 like a meteor gone berserk.

It could not have happened at a worse instant. A crewmember said later that the Japanese fighters were like yellowjackets swarming out of a disturbed nest—and now the interior of the B-29 was being seared.

Red Erwin was now clutching a handful of hell, his eyes a mass of blisters, other crewmembers choking and vomiting around him. Smoke filled the cabin. Snatch Blatch, although not hit, went out of control. Simeral fought to prevent the bomber from hurtling earthward. Erwin struggled toward the pilots.

Co-pilot Stabler peered through the smoke in disbelief as a burning human being staggered toward him shouting, “Open the window! Open the window!” The heat could be felt from one end of the aircraft to the other, and it seemed certain the device would turn the B-29 into a blazing torch at any instant. Simeral screamed, “Get it out the window!”

Somehow copilot Stabler overcame his shock at seeing Erwin, afire, doing what no human being should be capable of accomplishing. Stabler managed to open the window and recoiled from the windblast. “Excuse me, sir,” the ever courteous Erwin said through his pain. He threw the flaming canister to the wind and collapsed to the floor in flames. Three hundred feet from the ground, Simeral pulled Snatch Blatch out of its dive to head for Iwo Jima, the nearest landing site affording medical aid.

“Go go, go. You Can Make it”

The crew turned fire extinguishers on the prostrate, burning body of Red Erwin. Stabler administered morphine to dull the pain. Through it all—the hours’ long trip back and days of surgery following—Erwin remained conscious.

At the Iwo Jima hospital, the doctors gave it their best shot: whole blood transfusions, internal surgery, and antibiotics to fight infection. For hours they labored to remove embedded white phosphorus from Erwin’s eyes. The chemical spontaneously combusts when exposed to oxygen, and as each fleck of incendiary was removed it would burst into flames, torturing the airman once again.

Through it all, Erwin has said, there was an angel by his side, saying, “Go, go, go. You can make it.” Everyone expected Red Erwin to succumb to the pain, if not the wounds. That night the officers of Erwin’s unit prepared a recommendation for the Medal of Honor.

The Only Medal of Honor for a B-29 Crew Member

At 5 the next morning they awakened General LeMay at his headquarters on Guam. LeMay took a personal interest in Erwin, sending his recommendation to Washington, D.C., and arranging to fly Red’s brother, who was with a Marine Corps unit in the Pacific, to his deathbed.

LeMay’s command transported Erwin from Iwo to Guam, where he could receive better medical care in his final hours. Eager to present Erwin his nation’s highest award before he died, LeMay canvassed the Pacific region and learned that there was only one example of the Medal of Honor anywhere—in a glass display case in Hawaii. An aircraft and men were dispatched. No one could find the key to the display case. The men smashed the case, grabbed the medal, and rushed back to Guam

There, just one week after his B-29 had nearly burned up from the inside, Erwin was rolled out in a stretcher. He was wrapped entirely in white with slits for his eyes and mouth. With his B-29 crew and Maj. Gen. Willis Hale watching, LeMay handed Erwin the medal—surely the only time an American was awarded a medal snatched from a showcase—and told him, “Your effort to save the lives of your fellow airmen is the most extraordinary kind of heroism I know.”

Through his bandages Erwin replied simply, “Thank you, sir.” LeMay had been certain the award would become posthumous. Erwin surprised everyone by refusing to die. Erwin became the only Superfortress crewmember to be awarded the Medal of Honor for action aboard a B-29 (although one of LeMay’s B-29 pilots, Michael Novosel, would receive the award 24 years later for action as a Huey helicopter pilot in Vietnam––at age 47).

Army Air Forces boss Arnold wrote a personal letter to Erwin: “I regard your act as one of the bravest in the records of the war.” Pilot Simeral later said Erwin’s was “an ordeal with the fires of hell.”

B-29s conveyed the new secret weapon to Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and Nagasaki three days later. Japan surrendered on August 15.

Erwin’s Post-War Recovery

Erwin’s war was not exactly over. He lived through more than two years in which the smells of burnt flesh and hospital disinfectant symbolized his constant, agonizing pain. In October 1947, after continuous hospitalization and 41 surgical operations—and just one month after the U.S. Air Forces separated from the Army to become an independent service branch—Erwin was medically discharged as a master sergeant.

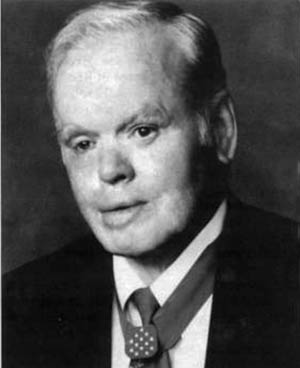

He had lost and regained his eyesight, had lost the use of one arm, and was covered with burns. He subsequently spent 37 years as a counselor at a Veterans Administration hospital in Birmingham, Alabama. Erwin died January 16, 2002, aged 80, and is interred in Birmingham, Alabama.

The Air Force has not forgotten Erwin’s dedication and presents an annual outstanding enlisted aircrew member award in his name. The radio operator position in the world’s only current airworthy B-29—Fifi, operated by the Texas-based Commemorative Air Force—bears a plaque honoring Erwin.

Respectful, religious, and ever self-effacing, Erwin would have wanted his fellow crewmembers to be remembered. In addition to those named above, the crew of Snatch Blatch included radar operator 2nd Lt. Lee Conner, bombardier 1st Lt. William T. Loesch, navigator Captain Pershing I. Youngkin, gunner Sergeant Herbert Schnipper, gunner Sergeant Vernon G. Widemeyer, and tail gunner Sergeant Kenneth E. Young.

This article is based on quotes from Henry E. “Red” Erwin, Sr., gathered in interviews conducted by the author over several decades, beginning in 1961.

What a heroic man . I researched who he was as I am currently refurbishing a hangar dedicated to him in raf Lakenheath and I’m glad I did .. I will surely pass his story on …

God bless you staff sergeant Henry Erwin

And all your family . What an honour

I wish I had known the story of this amazing American hero a few years ago when I had the privilege to ride in Fifi.

A credit to a Great State, in which I met my beloved bride of 26 years. God Bless this Great Man’s Soul and Memory.