By Eric Niderost

The sun had already set, but the western sky was still bright from its fiery departure not long before. To the east, across the broad Atlantic Ocean, sea fog was forming, a cottony mass that would soon obscure the horizon. At the moment, though, the visibility was good enough for Federal warships to subject Fort Wagner to a naval bombardment of increasing intensity.

It was the early evening of July 18, 1863, and Fort Wagner was one of a string of fortifications that guarded the approaches to Charleston, South Carolina. The fort was situated on the northern tip of Morris Island, a marshy patch of land that had immense strategic importance. The Confederacy depended on swift ships that could evade the Union’s naval blockade, which was designed to economically strangle the South. The blockade runners’ entry and exit into Charleston would be made simpler if they could enter under the protection of Fort Wagner’s guns.

For most Union soldiers, the emotional considerations were just as important as the strategic ones. Charleston was the place where the war began, the cradle of secession and rebellion. Confederate batteries had opened fire on Fort Sumter a little more than two years before, starting a fratricidal conflict with no end in sight. If the Federals took Fort Wagner, they would be one step closer toward their ultimate goal, the capture of Charleston.

The operation had been planned by Union Maj. Gen. Quincy Gillmore, the newly appointed commander of the Department of the South. Gillmore was an engineer who had earlier successfully taken the Confederacy’s Fort Pulaski. In a bold stroke he had secured the approaches to Savannah, Georgia. The general had land batteries in place but made sure that the Union fleet waiting just off the coast also would join the attack. Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, the commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was more than willing to cooperate.

The naval bombardment continued, the shells exploding in great gouts of smoke and flame. Some of the naval shells weighed 400 pounds. They were fearsome projectiles that when fired sounded like an express train as they hurled through the sky. One shell landed just offshore, and when it detonated the water where it hit erupted into a blossoming geyser of dead fish. Federal land batteries joined in the destruction, adding their weight of metal to the deadly proceedings.

But Gillmore was an experienced engineer, and he knew that barring a miracle a heavy bombardment alone would not secure the fort. It would have to be taken by a full-scale infantry assault. The Union general had 11,000 troops available, so manpower was certainly not lacking. But Gillmore had tried to take Fort Wagner a few days earlier, and the attempt proved to be an abortive and bloody fiasco. The first assault had taken place without artillery support, but Fort Wagner obviously was going to be a difficult objective to capture.

Union planners ultimately decided three infantry brigades would take part in the attack. Brig. Gen. George Strong’s brigade would be in the lead with the other two in support. But who would be in the vanguard of Strong’s effort? It was a position of honor and great risk, requiring a regiment of uncommon coolness and bravery. Strong chose the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Colored at the urging of its commander, 25-year-old Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

The 54th Massachusetts was a black regiment with white officers. Shaw, who was a scion of a prominent Boston abolitionist family, wanted to be given a chance to prove his men were just as good as other Union soldiers. His men had seen their first action only two days before and acquitted themselves well. They were tired, their clothes were damp from a previous rain, and they were hungry, but by the same token they were still determined to prove themselves.

As the shadows deepened and the bombardment abated, Shaw positioned his men for the coming assault. The black soldiers were mostly silent, a change from their usually ebullient mood when in ranks. The mood was not one of fear, but one of determination to see the task through. When a shell passed over, a few displayed some all too human nerves by shifting about, but quickly steadied after one black soldier made a joke. Referring to their Confederate foes in the fort, he said, “I guess they kind of expects we’re coming!”

The men of the 54th Massachusetts often had to deal with racism and negative stereotyping that was almost as deadly as enemy bullets. It was something of a miracle that they were in the Union Army at all. In the mid-19th-century virtually all whites considered Caucasians—especially those of Western and Northern European stock—to be biologically superior to all other races. This was a belief that was so deeply embedded in American culture it was taught in schools and even accepted by most educated people of the time.

When the American Civil War began, recruiting stations in the North firmly rejected black men who attempted to enlist. This was, after all, a white man’s war dealing mainly with secession and Southern rebellion. Northern abolitionists might see this fight as a crusade against slavery, but they were a distinct minority of the Union population.

Many white Union soldiers shared the prejudices of the time. They did not want to fight side by side with black soldiers because of their misguided belief in racial superiority. Racial bigotry aside, there were genuine doubts that the black men could do the job. In this line of reasoning even free blacks were descendants of slaves. A kind of cringing inferiority complex was deeply inbred from the centuries of servitude. It was so deeply inbred that even free blacks inherited this trait. William Channing Gannett, a teacher of former slaves, had firm opinions on the subject. “Negroes—plantation Negroes, at least—will never make soldiers in one generation. Five white men would put a regiment [of blacks] to flight,” he wrote.

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln detested slavery but was no abolitionist. As the nation’s chief executive, he had other priorities. Hs main goal was to end the rebellion and restore the union as soon as possible; everything else was secondary to these main objectives. Lincoln also harbored some doubts about how well black men could perform in battle.

Another matter to be considered was the sensitivity of border slave states. Kentucky, for example, was a slave state with strong Union and Confederate sentiments. “I hope that God is on my side, but I must have Kentucky,” Lincoln once said. The president knew that if the border states left the union, the fortunes of war would shift in the Confederacy’s favor.

This fact was underscored when Union Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont issued a draconian proclamation that, among other things, freed the slaves of all Confederate sympathizers in Missouri. Joshua Speed, Lincoln’s oldest and best friend, advised the president to proceed cautiously on the sensitive political matter. “Do not allow us by the foolish action of a military popinjay to be driven from our present active loyalty,” he told the president. Lincoln took heed, and eventually Fremont’s own arrogance forced Lincoln to relieve him of command.

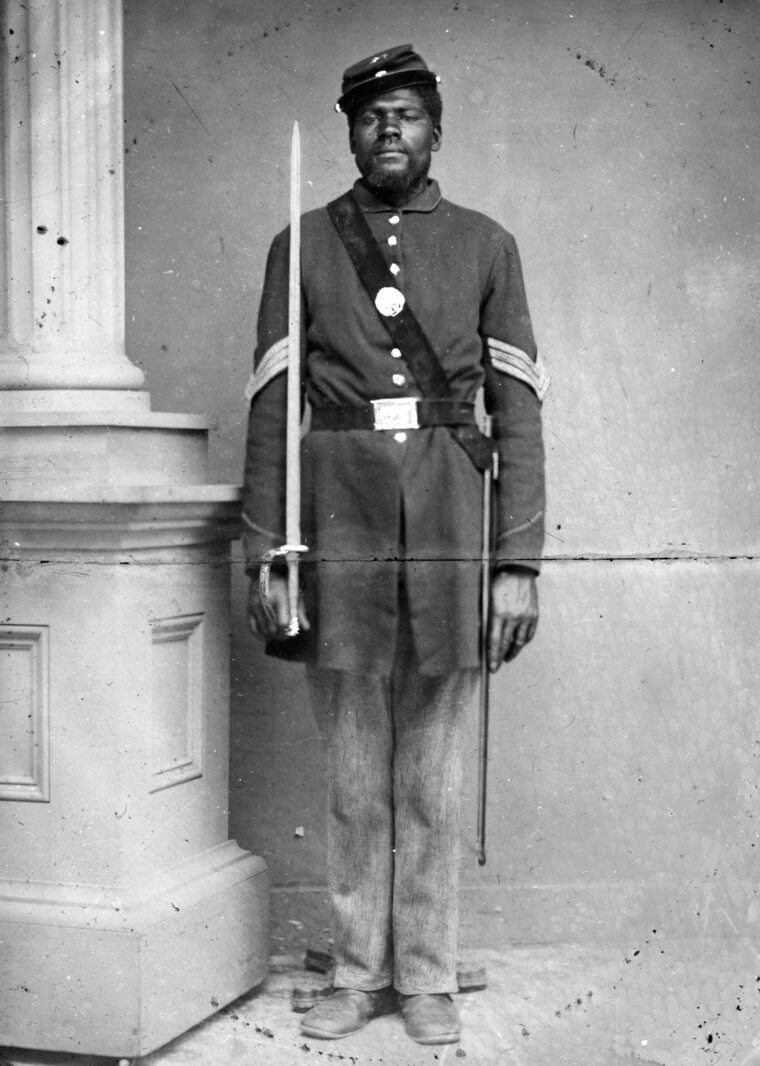

But as the war dragged on and Northern casualties mounted, there were fewer enthusiastic recruits willing to sign up. With enlistments declining, a new source of manpower had to be found. Many political and military officials in the North began to reconsider the possibility of black soldiers. In August 1862, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton authorized Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, military governor of the South Carolina Sea Islands, to raise five regiments of black soldiers.

The black soldiers proved their worth almost immediately. On November 7, 1862, the first of the five regiments, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, was mustered into Federal service. They experienced their first combat six days later when they were sent on a foraging expedition near Darien, Georgia. They ran into some Confederate troops, and though the resulting skirmish was small it loomed large in its psychological effect. The black soldiers were ex-slaves, yet they stood their ground and fought bravely.

In May 1863, two Louisiana black regiments took part in an assault on Confederate-held Port Hudson. The attack failed, but the sheer courage and tenacity displayed by the black soldiers was a source of wonder, even astonishment, to the white Federals who had also taken part. “The Negroes fought like devils, and they made five charges on a battery that there was not the slightest chance of their taking,” wrote a white Federal soldier.

The most famous black regiment of the conflict was the 54th Massachusetts, in large part because of its heroic assault on Fort Wagner. Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts conceived the idea of the regiment. A prominent abolitionist, he was certain black troops could make significant contributions to the Union war effort.

Frederick Douglass, a former slave and spokesman for the abolitionist cause, supported Andrew’s idea with unbounded enthusiasm. “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters ’U.S.’; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and there is no power on earth which can deny he has earned the right to citizenship,” wrote Douglas.

Recruitment was slow at first, mainly because Massachusetts had a small black population. But over the weeks more men enlisted, until the 54th Massachusetts could boast 1,000 effectives. Still more men signed up, enough to make a second regiment that was dubbed the 55th Massachusetts. But who would be the commander of the newly raised 54th Massachusetts?

To begin with, even the staunchest white abolitionist had little faith in the ability of black men to assume positions of leadership. By war’s end there were 7,000 officers in what was termed “United States Colored Troops.” Of this number, fewer than 100 were black, and many were eventually forced to resign due to racial bigotry. It was assumed that whites had superior intelligence and ability, although the smartest blacks might make good non-commissioned officers and become sergeants.

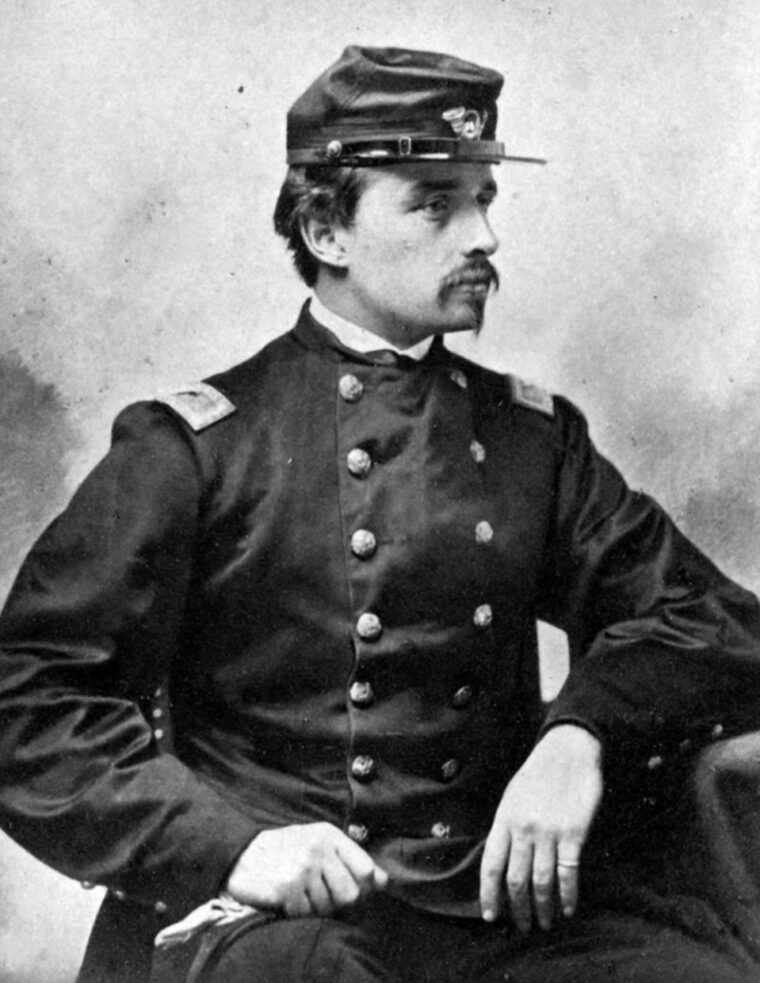

Robert Shaw Takes Command

Governor Andrew asked Shaw to take command of the 54th Massachusetts. His abolitionist credentials were impeccable. His parents were part of the abolitionist movement, and he had seen combat at Antietam the previous year. Shaw initially rejected the offer. He did not want to leave his existing unit, the 2nd Massachusetts, because he had grown attached to his men. There was also a feeling that commanding black troops might be a downgrade of prestige with a subsequent loss of face.

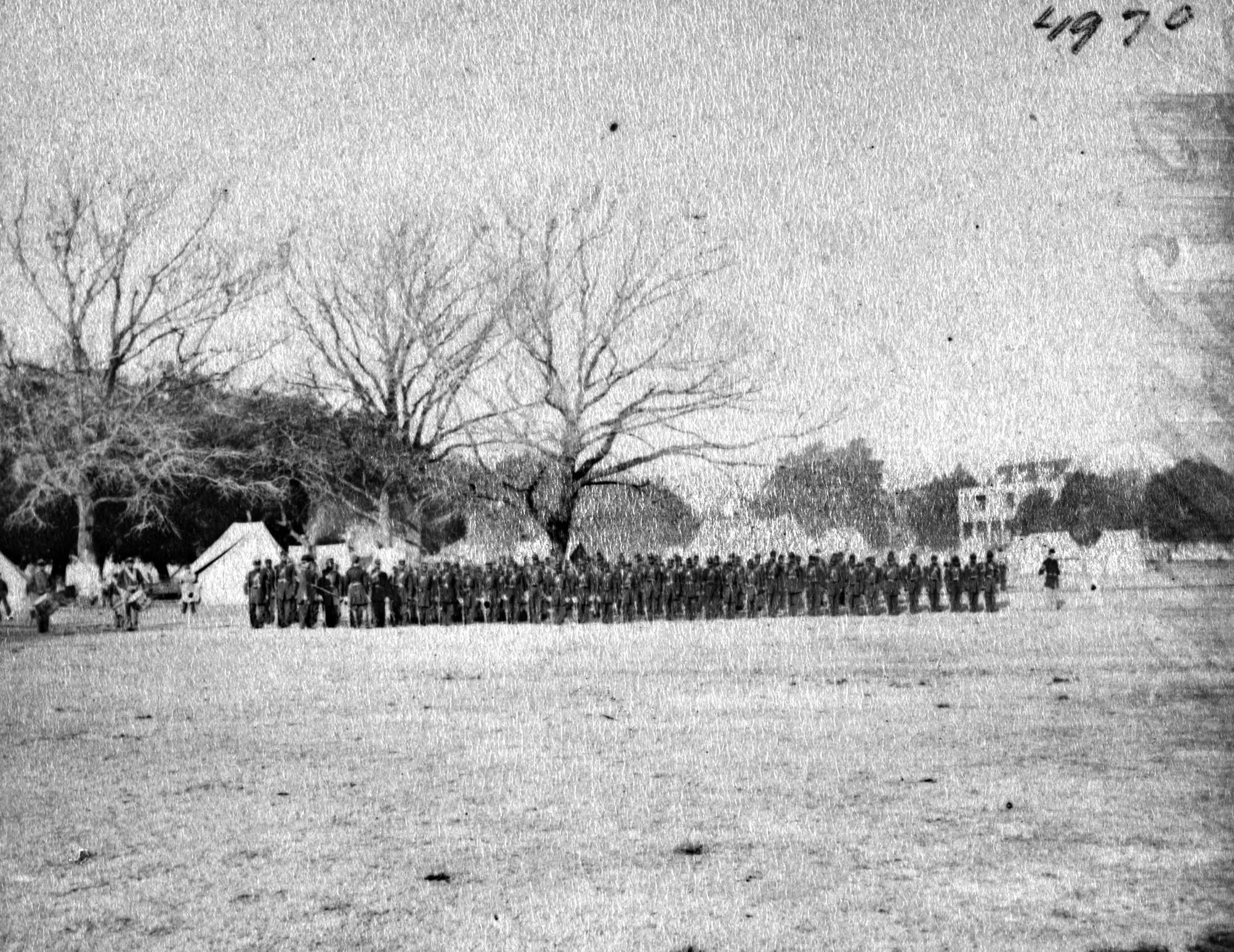

After discussions with his parents, Shaw overcame his doubts and took command with no regrets. By April 1863, Shaw and his men began drilling at Readville, Massachusetts, a town near Boston. The black soldiers encountered racism and prejudice at every turn, but these experiences made them even more determined to succeed. Shaw was determined to stand by his men no matter what difficulties might stand in their way.

The soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts were dismayed when they learned that they were to receive $10 a month pay, which was a full $3 less than their white counterparts. Shaw also was indignant and informed Governor Andrew that the entire regiment, including the white officers, would refuse pay until the rank and file got equal compensation as other Massachusetts regiments. Despite this, black soldiers would not receive equal pay until 1864.

The blacks of the 54th Massachusetts made exemplary soldiers, and this frankly surprised and amazed white visitors to their encampment. In a March 1863 letter Shaw himself expressed wonderment. “The intelligence of the men is a great surprise to me,” he wrote. ‘They learn all the details of guard duty and camp service more readily than the Irish I have had under my command.” Shaw was a white man of his time, naturally assuming that while slavery was unjust people of color were biologically inferior. After a few weeks Shaw was open-minded enough to change his views and became proud of how well the men preformed their military duties.

Massachusetts Surgeon General William Dale inspected the training camp and also came away favorably impressed. “The barracks, cook houses, and kitchens, far surpassed in cleanliness any I have ever witnessed, and were models of neatness and good order,” Dale reported. He went on to say that the cooks were outstanding because they had been employed in that capacity in civilian life. There is irony in this statement that Dale fails to understand. They may well have been fine cooks, but they probably entered the profession because racism barred them from other occupations.

Not long after the regiment was formed news was received that the Confederate Congress administered a sharp warning to potential black soldiers and their white officers. Armed black soldiers evoked nightmare images of servile rebellion in the minds of many slaveholders, and the Confederate Congress was determined to nip this effort in the bud if it could. Any black soldier caught in arms against the South risked death or enslavement if taken prisoner. White officers in command of such soldiers risked execution as malcontents inciting slave rebellion.

Lincoln immediately countered such measures, firmly declaring that for every Union soldier executed a Confederate soldier would also be shot. In similar fashion, for every federal soldier enslaved, a Confederate prisoner of war would be forced to perform hard labor. Lincoln’s decrees neutralized Confederate threats, but in several instances, for example, at Fort Pillow in 1864, enraged Confederates wantonly slaughtered black troops who were attempting to surrender.

In the meantime, the 54th Massachusetts continued to train. On May 18, 1863, Governor Andrew presented the regiment with its flags. For the most part, the Union Army followed the British tradition of having both a national color and a regimental color. Many thousands of citizens also came to witness the flag ceremony, including such prominent abolitionists as Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass.

Ten days later the 54th Massachusetts made its formal debut by proudly marching down the streets of Boston on their way to a transport that would take them south. Shaw, who was mounted on a magnificent chestnut horse, led the way. He was followed by the standard bearers and successive ranks of blue-clad black soldiers. Thousands of spectators lined Boston’s streets, cheering lustily and waving U.S. flags. Women waved handkerchiefs, which was a custom of the period, and important dignitaries watched the procession from a reviewing stand.

The regiment wound its way through the heart of historic Boston, passing through the famed Common and by the State House. In later years a heroic bronze monument dedicated to the 54th Massachusetts would be placed just opposite the State House, not far from where they made their triumphal passage. When the 54th Massachusetts passed a house on Essex Street, abolitionist Garrison was standing on its balcony next to a bust of John Brown. The symbolism was apt; if the martyr Brown had lived to see this spectacle, he would have heartily approved.

Finally the 54th Massachusetts reached the docks, where its soldiers boarded the steamer De Molay. The unit’s destination was Port Royal Island, South Carolina. Once it arrived, it would report for duty in the Union’s Department of the South. The voyage was uneventful, though it must have been interesting to the vast majority of the 54th Massachusetts men, most of whom had never seen the ocean.

Once they arrived, the regiment soon became disappointed. Its soldiers were immediately assigned work in labor details. Once again, a form of latent racism came into play, based on the notion that blacks were only fit for manual labor. Disappointment soon turned into disillusion as the weeks dragged by and they were still employed in digging, hauling, loading, and unloading. The spade and pick had replaced the rifle-musket and bayonet, and the men felt a growing frustration with this menial labor.

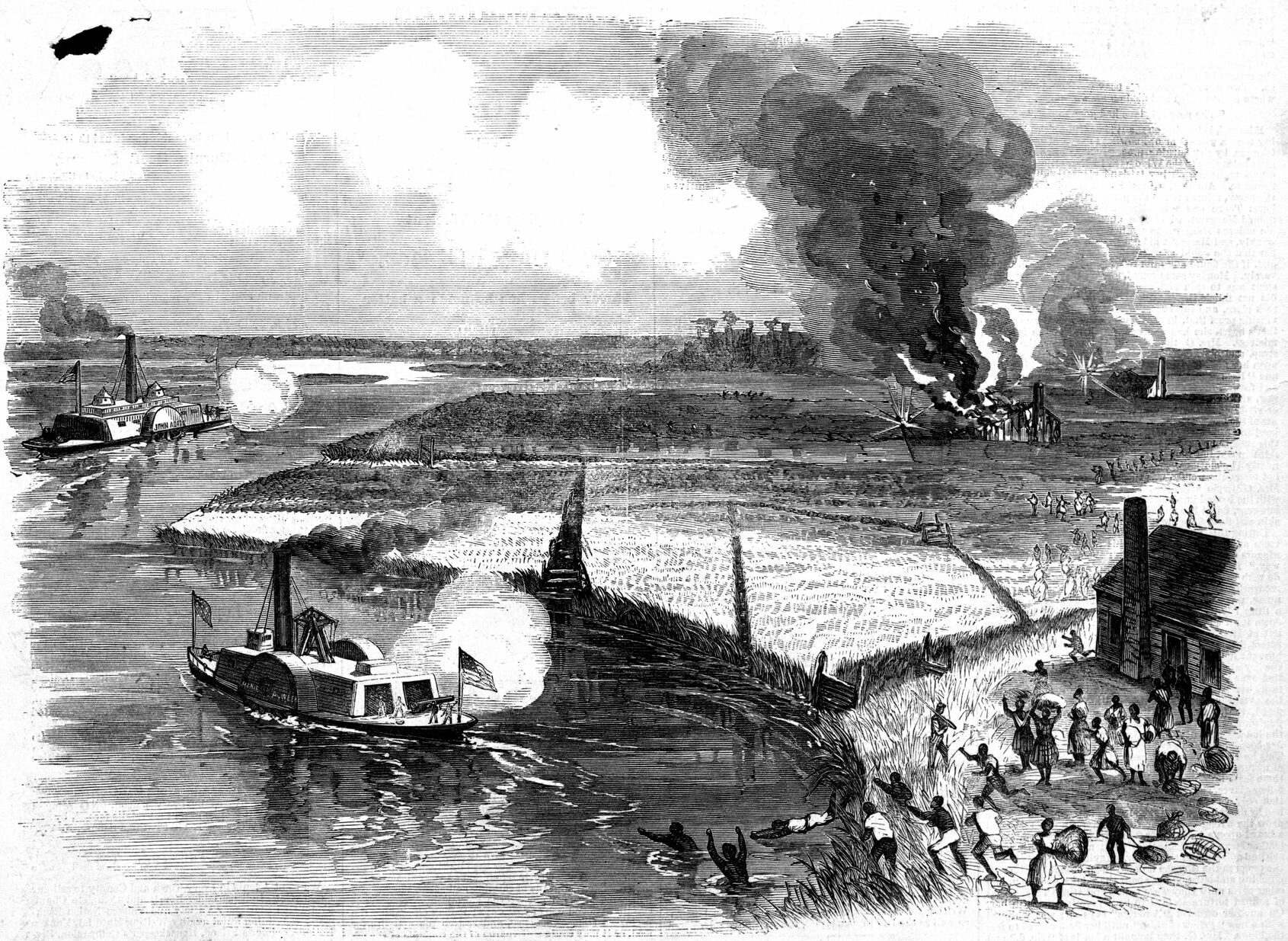

Shaw also felt frustration, but then out of the blue an opportunity came for the 54th Massachusetts to prove its worth, or so it seemed. The regiment joined Colonel James Montgomery’s 2nd South Carolina Colored Volunteers on a raid on Darien, Georgia. Maj. Gen. David Hunter, commander of the Department of the South, had ordered the expedition.

The Darien raid was an embarrassing and ultimately pointless fiasco. Darien, a small town of no particular importance, was sacked and thoroughly looted. Once the plundering was finished Montgomery ordered Shaw to put everything to the torch. Disgusted at this barbarity, Shaw reluctantly obeyed, but complained later to the acting adjutant general of the department. Later Lincoln relieved Hunter of command.

The 54th Massachusetts was then ordered with some other Union troops to take part in a feint on James Island. This feint was designed to divert Confederate attention from a new assault on Fort Wagner that was scheduled to take place in a few days. The James Island expedition was commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry, who was later to be George Armstrong Custer’s superior during the ill-fated Sioux campaign in 1876.

The Confederates rose to the bait, attacking the James Island expedition on the morning of July 16, 1863. The 54th Massachusetts was still in bivouac when the Confederates attacked, and Terry’s entire command seems to have been taken somewhat by surprise. Shaw’s men quickly formed up. They were ready for any action, but the real heroes of the skirmish were the picket Companies B, K, and H, posted about a mile in advance of the regiment.

The pickets were outnumbered but gave ground stubbornly, fighting for every foot of soil as they slowly fell back. The black soldiers fought courageously, and there were many acts of individual bravery. Sergeant Joseph Wilson of H Company killed four Confederates before a fifth shot him in the head. The Confederate artillery opened up, and rebel bullets peppered the black solders with a hail of lead.

The 10th Connecticut was poorly positioned and was threatened with complete destruction, but the 54th Massachusetts’s heroic holding action allowed the white regiment to escape at the double-quick. The Confederate attack ran out of steam, and soon the Federals heard the welcoming boom of Parrott guns from the armed transports John Adams and Mayflower. Their captains had earlier positioned the transports along a creek on the Union right flank.

The Confederates promptly withdrew. The courageous stand of the 54th Massachusetts had blunted and ultimately doomed the Confederate attack. The regiment had performed well in its baptism of fire, despite the terrifying sights and sounds of battle. The 10th Connecticut was particularly grateful and showered its black comrades in arms with praises.

Leading the Attack on Fort Wagner

When General Strong heard of the 54th Massachusetts’s performance, he asked Shaw if he would like his regiment to take the lead in the coming assault at Wagner. Shaw readily agreed because a successful attack on the Confederate work would put to rest any lingering doubts about how well blacks performed as soldiers.

The 54th Massachusetts had been bloodied in the skirmish two days before, but all knew the coming test was the regiment’s true baptism of fire. The regiment was formed in a column of wings, with the right wing resting near the sea. The men were then ordered to lie down while the final arrangements for the attack were sorted out. The 54th Massachusetts’s rifle-muskets were loaded but not capped; that is, a percussion cap would not be placed on the hammer of each weapon. The reason for this was that the initial assault was to be a bayonet charge. They waited in this position for about a half hour, adrenaline coursing through their veins, until given the signal to advance.

The 54th Massachusetts would not be alone in its endeavor. Three brigades would take part—two attacking, and the other held in reserve. The 54th Massachusetts’s immediate support was provided by the 6th Connecticut, 48th New York, 3rd New Hampshire, 9th Maine, and 76th Pennsylvania. This was going to be a supreme test, and every man in the Massachusetts regiment knew it.

Fort Wagner was going to be a hard nut to crack. The fort was named for Confederate Lt. Col. Thomas M. Wagner, a South Carolina state senator and former railroad executive before the war, who had been killed when a gun exploded during an inspection of Fort Moultrie on July 17, 1862. From a distance the fort looked like a series of irregular dunes, in essence a sand heap, but this was an illusion that hid its real strength. The work measured 250 by 100 yards and straddled an area from Cumming’s Point on the Atlantic Ocean to the east to the impassible Vincent’s Creek swamp to the west.

Wagner’s parapets were sloped and made of sand and earth, structures that rose some 30 feet high. The walls were strengthened by sandbags and palmetto logs. There were 11 guns in the fort, the largest of which was a 10-inch Columbiad that fired a 125-pound shell. Wagner also boasted a large bombproof shelter that featured a timber framework topped by 10 feet of sand.

The fort’s landward face, which was the area where an attack was feasible, was protected by a water-filled ditch measuring 10 feet wide and five feet deep. In addition to the moat, an assault force also would have to deal with a prickly array of razor-sharp palmetto stakes and deadly land mines. The approach to the fort’s landward side had its own difficulties. It consisted of a strip of beach that gradually narrowed. This strip became even narrower at low tide when the sea had somewhat retreated. Any attacking group would be trying to advance into what was in essence a bottleneck.

Brigadier General William Taliaferro commanded Fort Wagner’s determined Confederate garrison. Wearing a full beard that concealed much of his face, Taliaferro was a veteran who had long expected an all-out Union assault. The garrison consisted of approximately 1,700 men who belonged to the 51st and 31st North Carolina Infantry Regiments and an assortment of artillery companies. The most dangerous assignment during the Union bombardment was to man the shot-torn parapets. Taliaferro gave this risky duty to the Charleston Battalion, which was defending its home turf and determined to repulse the Federals come what may.

“Double Quick and Charge!”

As evening drew on the bombardment slackened, signaling a new phase of the effort: the frontal infantry assault. It was a moment of truth, and every man in the 54th Massachusetts was aware of it, but no one flinched from his duty. The 600 men were arrayed into columns of wings, five companies in each wing. Company B was assigned the right flank, near where the surf rolled onto the beach. Shaw commanded the first wave, with the national colors nearby. Lt. Col. Edward Hallowell was right behind, stationed with the regimental flag and the second wave.

General Strong appeared mounted on a spirited gray horse and accompanied by two aides and two orderlies. He decided to give the 54th Massachusetts some encouragement. “Boys, I am a Massachusetts man, and I know you will fight for the honor of the state,” he said in a booming voice. Strong acknowledged the men were tired, but Wagner’s garrison also was tired, he told them. “Don’t fire a musket on the way up, but go in and bayonet them at their guns,” he said.

At this point the general pointed to the flag bearer and asked, “If this man should fall, who will pick up the flag?” Shaw stepped forward, removed a cigar from his mouth, and quietly said, “I will.” Shaw’s response set off a round of cheers from his men. His address over, Strong galloped down the beach. Night soon arrived. It was time for the assault.

Colonel Shaw gave some last-minute instructions to the men before ordering the advance. “Move in quick time until within a hundred yards of the fort, then, double quick and charge!” he ordered. Shaw raised his sword and motioned for the men to advance. They responded at quick time, moving with bayonets fixed and muskets at the right shoulder. As the beach narrowed, the formation was funneled into a V-shape, but the men did not slow their pace.

“Forward, 54th!”

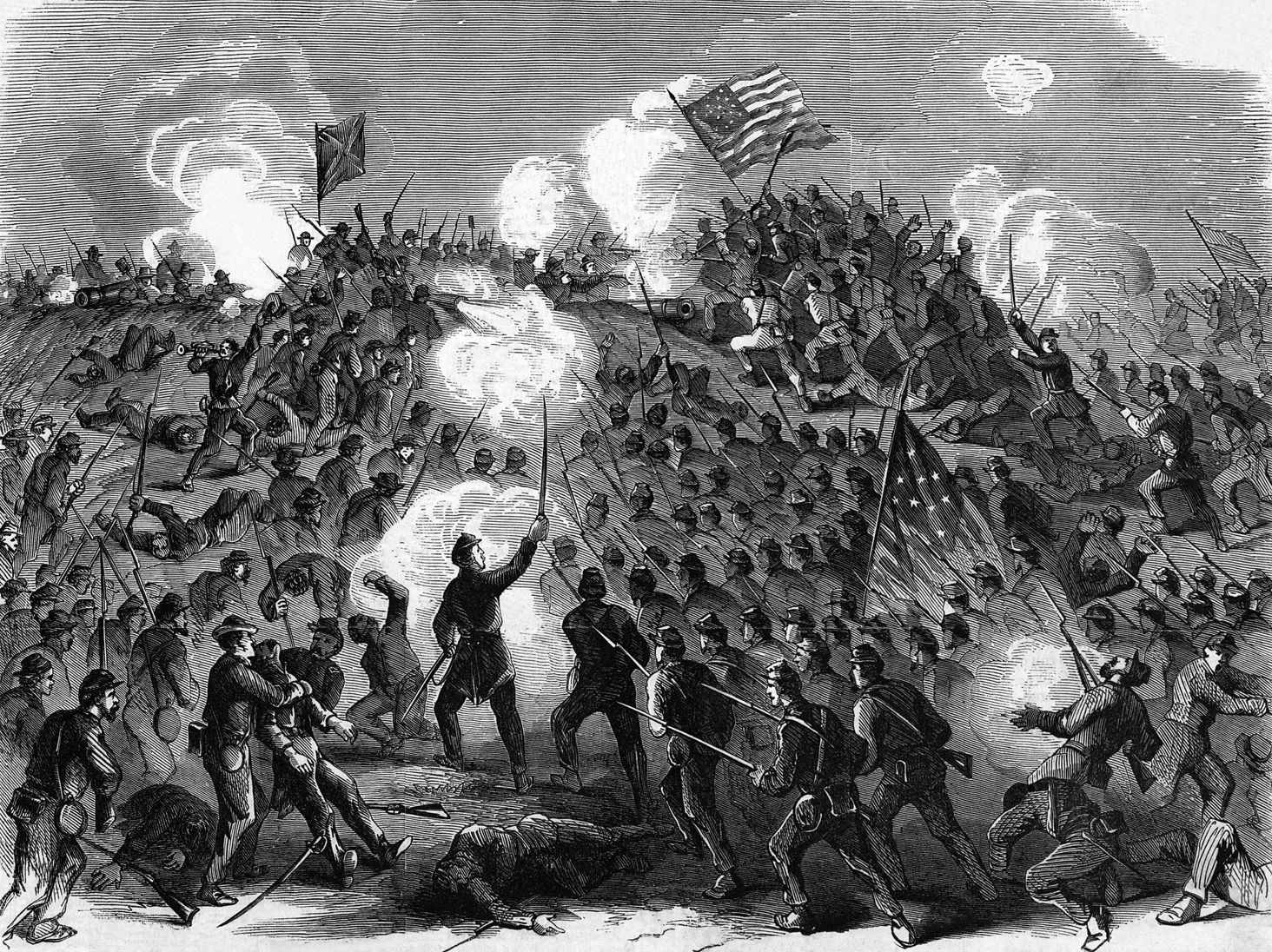

As Fort Wagner’s ramparts loomed closer, the 54th Massachusetts advanced to the double-quick; that is, a jogging pace. Then they broke into a headlong charge. The Confederates were ready. The rebel gunners rammed charges into the guns that had not been disabled by the Union bombardment. When the blue ranks were about 150 yards away, the fort’s commander gave the order to fire.

Confederate cannons roared to malevolent life, great sheets of smoke and flame pouring from their muzzles. Gray-clad infantry poured a heavy fire into the advancing Federals. It seemed as if no one could withstand this leaden storm, but somehow Shaw and his men kept advancing. Muskets balls and canister ripped into human flesh. The canister killed, maimed, and eviscerated human bodies with horrifying ease. Men screamed in agony, clutching bloody wounds that in many cases would prove lethal, but the survivors pushed on.

It was fully night now, and the assault was illuminated by bright flashes of artillery fire and smaller flickering lights of musket discharges. The 54th Massachusetts surged over the fort’s sharpened stakes and plunged headlong into its water-filled moat. The earlier bombardment had filled some sections of the moat with sand, but in other places the soldiers had to wade in water three feet deep or more.

When the Union soldiers reached the base of the ramparts, the Confederates began lobbing crudely made hand grenades at them. In some places, fighting was hand to hand with no quarter asked or given. Many Confederates were enraged that black soldiers were being used against them. Against all odds, Shaw and a handful of men managed to reach the top of the ramparts. Shaw waved his sword and shouted “Forward, 54th!” but moments later he was felled by three bullets and instantly killed.

Many acts of courage were performed that night, but perhaps the experiences of Sergeant William Carney best illustrate the regiment’s heroism. Carney was advancing when he saw a regimental banner displaying the Stars and Stripes go down. Knowing its capture would be a disgrace too terrible to contemplate, Carney flung down his musket and rushed to take the flag from the fallen bearer.

Once Carney had a firm grip on the flagstaff, he began climbing Fort Wagner’s sandy slopes. Clusters of black soldiers, encouraged by the sergeant’s heroism, followed close behind, but rebel hand grenades exploded all around them and severely decimated their ranks. Carney continued forward, knowing that he and his flag were magnets for Confederate fire.

Carney kneeled down on the parapet, the flag draped around him. Shell fragments and bullets peppered the ramparts, but he remained unscathed. When it was clear the attack had failed, the sergeant’s mission was to rescue the flag from almost certain capture. As Carney made his way back, two Confederate bullets slammed into his body, but he refused to give up his precious burden, even when crossing the water-filled moat.

Amid the chaos a soldier from the 100th New York appeared to render assistance. Carney allowed the man to help but refused to part with the flag even for a moment. In his eyes, only a member of the 54th Massachusetts should carry the regiment’s national emblem. Carney reached the Union lines still clutching the Stars and Stripes. Seeing some men of the 54th Massachusetts nearby, he proudly shouted, “The old flag never touched the ground!” The onlookers responded with loud cheers.

Sergeant Carney’s heroism did not go unrewarded. For his heroism, he became the first African American Union soldier to win the nation’s highest distinction, the Medal of Honor. Given the prejudices that most whites had against blacks, Carney’s award is all the more remarkable. He survived the war, though his wounds were so severe that he was honorably discharged before the conflict ended.

The 54th Massachusetts had been decimated, the dazed and bloodied survivors falling back as best as they could. Many were badly wounded, but they gave up ground stubbornly even as they were forced to retreat. But the regiment’s heroic advance and subsequent repulse did not end the assault. After the 54th Massachusetts assault, the five white regiments took their turn in the Fort Wagner meat grinder. Colonel John L. Chatfield’s 6th Connecticut was next, arrayed in columns of companies. Chatfield crumbled early in the assault, his leg shot from under him, but he was saved from almost certain death by Private Bernard Haffy, who shielded his stricken commander from a hail of Confederate lead.

For one fleeting moment it looked as if the 6th Connecticut would succeed where the 54th Massachusetts had failed. Color Sergeant Gustave De Bonge took the regimental flag up Fort Wagner’s sandy slopes followed by approximately 100 Yankee soldiers, all wildly cheering amid the din of battle. De Bonge reached the summit and drove the flagstaff deep into the parapet sands. It was the last thing he ever did, because moments later a Confederate bullet smashed into his skull, hitting him right between the eyes.

By chance the 6th Connecticut had hit Fort Wagner’s weakest point. Demoralized by the hours of shelling they had been forced to endure, the 31st North Carolina had failed to occupy their post in the fort’s southeast bastion. Here was a possible opening for the battered Federals to exploit. Their nerves shattered, the 31st North Carolina was unreliable at this point, so Taliaferro frantically rounded up a few steadier men to plug the gap.

The moment of possible Union victory passed, never to return. The Confederates managed to get three howitzers into action, guns that raked the Union men with blast after blast of canister. “The genius of Dante could but faintly portray the horrors of that hell of fire and sulfurous smoke,” wrote eyewitness Elbridge J. Copp of the 3rd New Hampshire, ‘the agonizing shrieks of those wounded from bayonet thrust, or pierced by the bullet of the rifle, or crushed by fragments of exploding shell, sinking to earth a mass of quivering flesh and blood in the agony of horrible death!’

Each Union regiment gave it a try, only to be ripped to pieces by salvo after salvo of bullet and shell. “It was almost impossible to pass over [Wagner’s parapet] and live five seconds,” wrote S.C. Miller, the color bearer of the 76th Pennsylvania.

General Strong himself was badly wounded, hit in the thigh by canister. Dazed and in great pain, Strong realized there was no other option left except withdrawal. “Retreat in the best order you can!” he shouted. The general later died of his wound. The Union assault had ended in a bloody if heroic fiasco.

Bravery and Bayonets Against Impossible Odds

In retrospect the attack on Fort Wagner was gallantly executed but poorly planned. The Federals placed too much confidence in the naval bombardment, which was not nearly as effective as had been hoped. The Confederate garrison was also much stronger than expected. Usually there were certain procedures to follow before attacking fortifications, but for some reason they were ignored. The 54th Massachusetts and the other Union regiments were supposed to perform a miracle by the bayonet alone.

There were no special instructions for the rank and file attackers, no line of skirmishers, no engineers as guides, and no artillerymen to serve captured guns. No soldiers were assigned as sappers to cut away obstructions or even fill in the moat. Even the company officers had little real knowledge of the fort’s plan and layout, since they had been shown no map or blueprint of the work. In this way they were as blind as the men that followed them.

The casualty figures tell a somber tale of self-sacrifice and courage. On the Union side, 1,515 men were dead, wounded, or missing out of a total attacking force of 5,000. As might be expected, the 54th Massachusetts suffered horribly in the attack. Almost half of the regiment, 272 out of 600, was dead, wounded, or missing. The Confederate casualties were lighter and numbered 181 men.

Unable to take Fort Wagner by assault, the Union Army settled down to a protracted siege in which the fort was shelled on a daily basis. The Confederates eventually abandoned the fort on the night of September 6-7, 1863.

The attack of July 18 changed the way whites perceived black soldiers. The 54th Massachusetts was not the first black regiment ever raised, but the courage displayed by its soldiers in the face of almost impossible odds made a lasting impression and erased the remaining doubts many had about the use of black men in the military.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments