By Glenn Birdwell

Where is the prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defense, as that ten thousand men descending from the clouds might not, in many places, do an infinite deal of mischief before a force could be brought together to repel them?” When Benjamin Franklin asked this question, he could not have envisioned modern air-assault concepts and weapons. It would be 200 years before Hamilton Hawkins Howze combined cavalry and paratrooper tactics, coupled them with a new “horse” (the helicopter), and produced a totally new product—airmobile. Many of the details were ironed out under fire, and the first field manuals were written in blood in Vietnam.

The United States Army Tactical Air Mobility Requirements Board was established in 1962 under a directive from Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who asked the Army to “take a bold new look at land warfare mobility.” General Hamilton Howze was recognized as the officer with the necessary insight and experience to lead the effort. However, no innovative idea develops in a vacuum; existing or new concepts, tactics, and equipment are necessary components. Airmobile was no exception; some of the components were horse cavalry tactics, parachute infantry tactics, and the helicopter. Howze supplied the vision: battlefield mobility with a speed far superior to that of infantry, cavalry, or mechanized armor, although airmobile would be a mixture of all three.

Son of a Cavalryman

Howze was born into a military family in 1908. His father, cavalryman Robert L. Howze, had been awarded the Medal of Honor for action against the Sioux. His grandfather had been an infantry officer in the Confederate Army, and members of his family had served with Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in Cuba. His maternal great-grandfather and namesake, Hamilton S. Hawkins, had died in battle at Vera Cruz in the war with Mexico. With a warrior pedigree, Howze graduated from West Point in 1930 and was assigned to the 6th Cavalry at Fort Bliss, Texas. During World War II, Major Howze was operations officer for an armored division in North Africa and Italy.

Howze received a Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Legion of Merit during his career, and at various times he commanded infantry and airborne divisions, corps, and armies. He was not, however, primarily a combat commander. Instead, Howze was a superb organizer and administrator. No obstinate bureaucratic pencil-pusher type of administrator, he was instead a problem-solver and innovator. He was not a by-the-book officer who knew only the Army way. Rather, he had fresh ideas and was willing to try them.

General Billy Mitchell, one of the best-known “air-power” rebels of all time, was a Howze family friend. Mitchell had often visited the home of Robert Howze when Hamilton was a boy. General Robert Howze had later been the presiding officer at Mitchell’s courts-martial. Support for airpower fell with Mitchell, and Hamilton Howse learned to work within the system and advocated his initiatives in a nimble, agile, soft-spoken but ardent fashion. Airmobile was in many ways a revolutionary concept, but Howze used his personality and skills of persuasion to convince others of the utility and effectiveness of his approach.

“Aviation, the Cavalry of the Future”

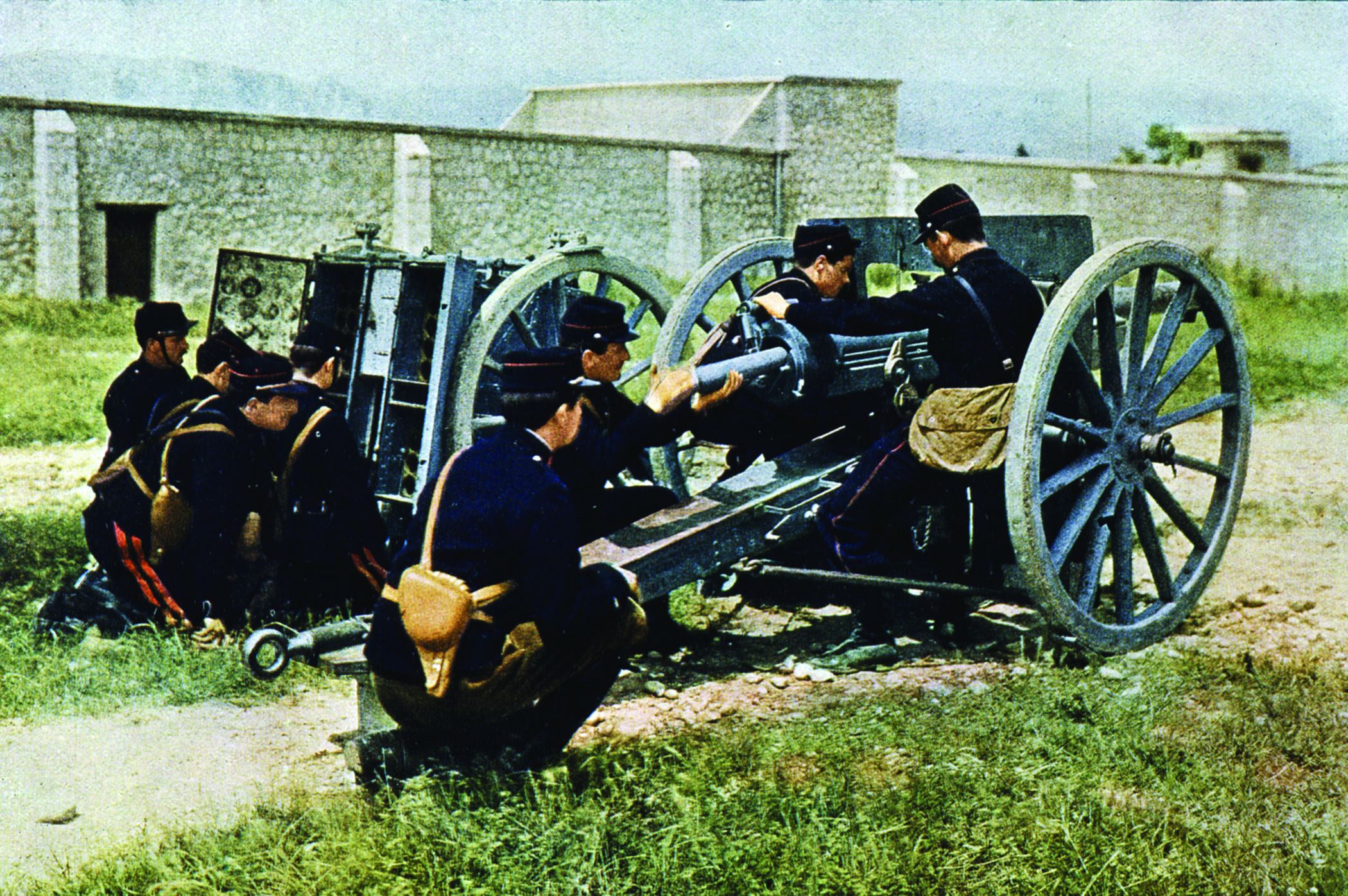

Along the way, Howze was quick to adapt the ideas of others. Three examples were A.A. Vandergrift, Roy S. Geiger, and James Gavin. Vandergrift, a future Marine Corps commandant, had in 1909 written a thesis entitled “Aviation, the Cavalry of the Future.” It was deemed unsatisfactory. Roy S. Geiger, another Marine Corps general, witnessed the nuclear bomb test on Bikini Atoll in 1946 and recognized the need for something new to replace old-style amphibious landings. Possibly the most significant air-cavalry philosopher was General James Gavin. He commanded the 82nd Airborne during World War II and wrote an article for Harper’s in 1954 entitled “Cavalry, and I Don’t Mean Horses.” In it, Gavin lamented the lack of units able to fulfill a cavalry function and stated the philosophical foundation for airmobile. “Cavalry is the arm of mobility,” wrote Gavin. “It serves a useful purpose because of mobility differential—the contrast between its mobility and other land forces.”

Gavin’s article suggested that mobile forces be used to screen the infantry, scout enemy positions, exploit breakthroughs, and fight delaying actions. He also recommended that the new units be “lifted by helicopters or light aircraft armed with automatic and antitank weapons.” Without the new units, Gavin warned, road-bound mechanized units would be exposed to ambush similar to the Chinese surprise attacks in Korea in 1950. Gavin’s article provided a rough outline for the airmobile concept. When Gavin went looking for someone to appoint as the first director of Army Aviation in 1955, he found a man whose airmobile vision was coupled with an ability to implement and execute—Hamilton Howze.

As director, Howze pushed hard for aircraft procurement, both helicopters and fixed-wing support aircraft. He also authorized unorthodox tests of helicopter capabilities. Howze saw to it that every weapon imaginable was strapped onto a UH-1 (Huey). In these efforts, Howze had the assistance of another helicopter visionary, Jay D. Vanderpool, who worked nights and weekends to prove that the helicopter was a superior weapons platform. Vanderpool pioneered the “nap-of-the-earth” flying technique. In writing the first airmobile field manuals, he borrowed language from an old 1936 cavalry manual. Using cavalry tactics and helicopters was a vision that was rapidly becoming reality.

Bureaucratic Limitations to Innovation

As early as 1957, Howze had a clear view of airmobile, as evidenced by a Pentagon briefing he delivered that year. In it, he presented a plan of defense against a hypothetical Soviet attack in Bavaria. Howze presented two scenarios. In the first, three Soviet divisions attacked one U.S. armored division. In the second scenario, Howze put the same three Soviet divisions against just one super-mobile U.S. Air Cavalry Brigade supported by combat engineers and artillery. Of course, such an air cavalry brigade did not yet exist. The U.S. armored division had hundreds of tanks and vehicles dependent on roads and intact bridges. The air cavalry brigade did not need roads or bridges. In fact, roads, bridges, and culverts could be destroyed or mined to frustrate the enemy. The Howze airmobile solution accomplished the delaying mission at a lower cost and with fewer casualties. In 1957 this was a unique, even revolutionary solution.

Howze left the Pentagon to command the 82nd Airborne from 1958 through 1961. In 1962, he was appointed to head the Army Tactical Mobility Requirements Board. The evolution from the 1957 map solution to leadership of the group that would create airmobile was fairly rapid for the hurry-up-and-wait Army. The deficiencies and limitations of existing units were apparent to all. Parachute infantry was airmobile of a sort, but once out of the plane, the “air” part was gone, and once on the ground, the “mobile” part was gone as well. Resupply and reinforcement depended on subsequent air drops tied to the vagaries of weather and enemy resistance. Armored units were confined to roads or open ground; infantry units were either road-bound or too slow in cross-country movement. What was needed was some type of highly mobile air cavalry unit that could dismount quickly, fight, remount, attack from a different direction, create enemy confusion, cut off enemy retreat, and provide an element of hard-hitting surprise.

By 1960, the Army was beginning to see that a new approach might be necessary and created the Rodgers Board to review Army aircraft requirements. Howze was a member of the board and tried to have some airmobile tactics, doctrines, and units included in the final report. However, the more radical Howze proposals were rejected and more modest proposals were made. The conservative-minded Rodgers Board recommended the procurement of more observation helicopters and suggested that further studies be undertaken.

New Administration, New Opportunities

In 1961, a new administration took over and the focus changed. At issue were the limitations of conventional units and the concept of massive nuclear retaliation. Conventional and nuclear forces were to be reevaluated. The new administration of President John F. Kennedy sought solutions presenting the possibility of a more flexible response. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara produced two memoranda in April 1962 addressing these issues. The first ordered the Secretary of the Army to review Army aviation requirements to “consider fresh, new concepts and give unorthodox ideas a hearing.” The second memorandum contained a short list of people whom McNamara suggested serve on the committee. The first name on the list was Hamilton Howze.

Howze convened the Army Tactical Mobility Requirements Board in May 1962. The Howze Board was composed of 294 individuals: 200 officers, 41 enlisted men (all Army), and 53 civilians. There was one Air Force general included as an observer only. There were seven working committees and eight working groups. The deadline was August 20. One copy of the report, addendums included, was to fit in a standard Army footlocker. Howze instructed the board to “undertake a review of the application of army aircraft and the traditional cavalry role of mounted combat, reconnaissance, and security. Special attention was to be given to determine to what extent conventional surface vehicles could be replaced by aircraft, both tactical and support.”

The Howze Board effort was no half measure. Suggestions were solicited from every corner. Questionnaires were sent to 400 officers and 300 letters went to aircraft industry employees. Tests were scheduled for Fort Bragg to simulate conditions similar to those encountered at Pusan in 1950. Further testing was scheduled for the Georgia swamps to simulate the conditions of Indochina. The pace was frantic. One group recorded 11,000 flying hours in six weeks. Forty-six different tests were done in May alone. One test compared the capabilities of conventional and airmobile infantry. With a helicopter lift capacity of one platoon at a time, the airmobile company initiated an attack over hilly, wooded terrain in just one hour, while the conventional infantry company took 24 hours to achieve the same objective. The tests were only experimental, but as Howze noted, they showed what was possible and what could be accomplished with speed, precision, maneuver, and firepower.

War Game Experiments: “That’s What We Mean by Air-Mobility”

The board also conducted war game experiments. One scenario scripted a Soviet invasion of Iran opposed by airmobile forces. The scenario had Soviet forces invading through passes in the Zagros Mountains. The airmobile units were able to engage Soviet forces more quickly and therefore much closer to points of entry. If the Soviet forces remained on the roads, they were severely degraded. If, on the other hand, the Soviet forces turned against the airmobile bases, U.S. armored units had time to move into line. At least in the game scenario, airmobile was able to execute maneuvers and tactics best described by the phrase “float like a butterfly—sting like a bee.”

Tests, war games, experiments, and reports were completed in a few months, and airmobile was scheduled for a full field demonstration in front of Secretary McNamara and other esteemed delegates. Howze narrated the action to the assembled grandstands as an enemy ridge was attacked 1,100 yards away. Howze explained that facing an enemy entrenched on high ground was the toughest field problem any army could confront. He explained that a conventional infantry attack, supported by armor, would take hours to mount and suffer many casualties. If the new airmobile units could do this, said Howze, they could do anything.

In the test, 105mm howitzers fired three rounds apiece in eight seconds, followed by four Mohawk aircraft dropping one 1,000-pound delayed-fuse bomb apiece. The fuse-delay bombs were designed to bounce over the ridge before exploding on the reverse slope. Air Force dive-bombers were to be included at this point, but low clouds deleted this element. That made this purely an Army show, which suited Howze just fine. After the Mohawks, four helicopter gunships attacked the fortifications with machine guns and 2.75-inch rockets. Then came the climax—flying low, from behind the grandstands, at 110 miles per hour roared 30 Hueys loaded with infantry. Flying straight into the dust and smoke, they dismounted and attacked. Howze turned to McNamara and said, “Sir, from the moment the enemy could have known an attack was coming to the time our infantry was dismounted and on top of him was exactly 120 seconds. That’s what we mean by air-mobility.”

Stiff Opposition from the Air Force

The final report of the Howze Board was submitted in August 1962. Written by Howze himself, it contained some radical recommendations. Five air assault divisions were to replace three infantry and two airborne divisions. Each of the new divisions would have 459 aircraft and 1,000 vehicles. By contrast, a regulation 1962 division had 100 aircraft and 3,452 vehicles. Everything in the new air assault division was to have airlift capability, thereby eliminating the need for numerous vehicles. Similarly, division artillery was limited to 105s; 155s and 8-inch howitzers were eliminated. The heavier guns were to be replaced by 24 Mohawk (fixed-wing) bombers and 36 Huey gunships.

Everything revolved around the use of Army air assets—primarily helicopters, but also experimental fixed-wing aircraft like the Mohawk. The report was far reaching and cutting edge. It even included a description of areas where airmobile would be most effective. Prophetically, Southeast Asia was seen as a place where the new unconventional airmobile might excel.

Although Howze’s radical creation was later compared to the revolutionary formation of the first armored units, negative reaction, especially from the Air Force, was swift and abundant. General Curtis LeMay said the Army was creating its own air force and convened an Air Force Board to refute the Howze Board findings and recommendations. The Air Force board, besides charging the Howze Board with ignorance of Air Force capabilities, flatly stated that the U.S. Army was not competent to judge air warfare.

Testing the 11th Air Assault Division

McNamara favored adoption of the Howze proposals, but his report to Congress contained this statement: “The Howze recommendations are so revolutionary in character they need to be tested before implementation.” In February 1963, the 11th Air Assault Division was activated at Fort Benning, Georgia, to begin conducting 18 months of new tests and exercises. The tests and exercises yielded a positive recommendation by the Army chief of staff that was then forwarded to the Joint Chiefs. With only one dissenting vote—Air Force General John McConnell—the Joint Chiefs endorsed the Army findings.

In June 1965, McNamara authorized the organization of the 1st Air Cavalry Division. It combined the test division resources with those of the 2nd Infantry Division to produce a unit with 15,787 men, 428 helicopters, and 1,600 vehicles. Of the 428 helicopters, most were troop transports, but 39 were Huey gunships. The fixed-wing Mohawks were no longer part of the equation, having been sacrificed to the animus of the Air Force. With the activation of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), Howze’s vision had become reality. Now it had to be tested in combat. The 1st Cavalry shipped out to Vietnam in August 1965.

From Vietnam to the Gulf War: Airmobile in Action

Airmobile subsequently would win many victories in Vietnam, but the eventual U.S. strategic defeat left the airmobile concept bruised and bloodied as well. Helicopter warfare became associated with defeat. The helicopter was seen “an excellent carrier for the transportation and disposition of troops that could be modified into an excellent, if not indispensable support weapon. It permitted American forces to penetrate deeply into enemy-held territory [and it] provided rapid transport as well as combat readiness.” However, it could not win the war by itself. Many believed that in Vietnam the U.S. Army was locked into an attrition/body-count mentality, and to accomplish these goals, they had substituted a tactic—airmobile—for an overarching strategy.

Association with the Vietnam experience made helicopter warfare fall out of favor for a time. Slowly, however, the wisdom of the Howze vision became more apparent. By 1990, almost all of his recommendations had been implemented. The airmobile ideas of 1962 reemerged with a vengeance using 1990s technology and were used to great effect in the 1991 Gulf War. In it, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) was engaged for 60 of the 100 hours of ground combat. In the early hours of February 24, 1991, the 1st Brigade of the 101st, flying in 60 Blackhawks, seized a forward operations base 120 kilometers inside Iraq. The sudden appearance of the American troopers so completely surprised and unnerved the Iraqi defenders that they quickly surrendered. This unit was the first to supply the pictures of Iraqi soldiers trying to surrender to helicopters in flight. Certainly, even the imaginative Howze could not have envisioned such an eventuality.

The next day, the 3rd Brigade, lifted by 63 Blackhawks, moved 155 miles behind the retreating Iraqi Army and cut off its escape route out of Kuwait. Iraqi forces were trapped on a section of Highway 8—the Basra to Baghdad road—and totally annihilated. The extent of the destruction compared favorably to that of the German Army in the Falaise Gap in 1944. The air-cavalry had been responsible for closing the back door and shortening the war.

The maneuvers of the 101st Airborne in the Gulf War were textbook examples of air-cavalry as envisioned by Hamilton Howze. Speed and maneuver had achieved surprise and tactical superiority, and a flawlessly executed blocking maneuver had ensured the total destruction of enemy forces—cavalry tactics perfected by Nathan Bedford Forrest almost 150 years earlier and resurrected by Howze in 1962. In doing so, Howze produced a totally new concept of 20th-century battlefield mobility that continues to flourish in the 21st century.

As a practitioner of the Airmobile concept, 2 tours in Vietnam as a pilot in the UH-1 and OH-6, I doubt that it will ever go away.

This is an excellent article.

Thank you.

This is a good article.

Some of the interim history has been passed over. Much of the early use of helos was pioneered by the Marines.

The first Marine helo squadron was formed at Quantico shortly after WW2. It was, and still is, known as HMX-1, “X” for Experimental.. Today it is best known for transporting the US President. It also supports all of the training at Quantico.

Based on various trials by HMX-1, the first use of helicopters in combat was by the Marines in the Pusan Perimeter in Korea during July-Sept 1950.

Later the Marines used helos for resupply and troop movements.

As the capabilities of helos became better known, they were in wide use everywhere by the end of the Korean War. They are perhaps best known for evacuation of wounded to the MASH units. They made a huge difference. About 93% of the wounded who made it to the MASH survived.