By Allyn Vannoy

In the spring of 1942, the Allies were hard pressed battling German U-boats in the Atlantic as Britain was struggling to feed its people. The German subs were sinking thousands of tons of Allied shipping each week, causing American and British planners to seek any means possible to deal a blow to the German war machine.

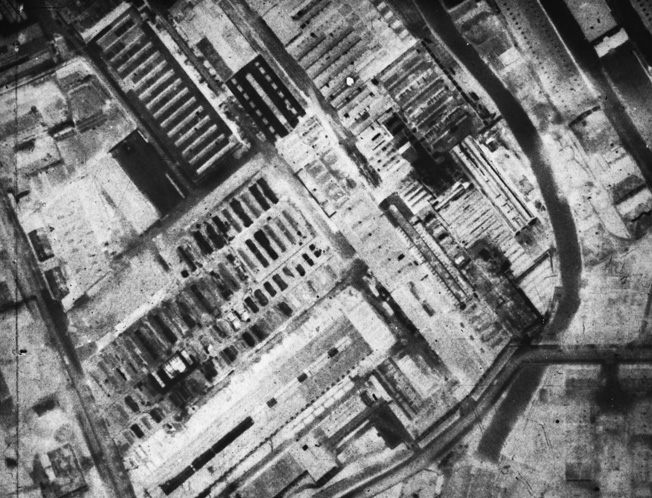

Because of the havoc being wrought by Hitler’s U-boats, the MAN (Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg) factories at Augsburg, in Bavaria, were high on the list of priority bombing targets. MAN’s diesel engine manufacturing plants produced roughly half of Germany’s U-boat engines. But reaching the target and returning involved a flight of 1,250 miles over enemy territory. With the navigation and bombing aids then available, it was determined that the chances of a night attack pinpointing and destroying such an objective, given the relatively small target area of the facilities, were remote, and a daylight precision attack, based on experience, was considered too costly.

The Avro Lancaster Changes the Equation

In early 1942, the Avro Lancaster bomber became available. The aircraft was powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, manned by a crew of seven, and outfitted with a defensive armament of 10 .303-caliber Browning machine guns. If there was a problem with the bomber it was that the range of the .303-caliber machine guns was too short to provide sufficient protection for the aircraft, though these were later upgraded, in part, with .50-caliber guns. The aircraft had a cruising speed of 210 miles per hour, a top speed of 287 miles per hour at 11,500 feet, and could carry a bombload of 14,000 pounds.

The prototype Lancaster had been delivered to the Royal Air Force for operational trials with No. 44 Squadron at Waddington in September 1941. The unit was dubbed the “Rhodesian” squadron since some 25 percent of the squadron’s ground and air crewmen were from Rhodesia.

With the aircraft’s relatively high speed and defensive armament, it was considered possible that a force of Lancasters could reach Augsburg if they went in at low level, underneath the German early warning radar. It was also felt that Lancasters flying on the deck could not be subjected to attacks on their vulnerable underbellies.

With the availability and increased capability of the Lancaster, consideration was again given to the idea of conducting a precision attack in daylight on Augsburg. But much would depend on the route used to reach the target.

The RAF had compiled a reasonably accurate picture of the disposition of enemy fighter units across Western Europe. In early 1942, half the Luftwaffe’s fighter force was deployed to the Eastern Front and a quarter to the Balkans and North Africa. Most of the remaining squadrons, if not earmarked for Germany’s defense, were stationed in Norway or the Pas de Calais area. Royal Air Force Bomber Command sought to find a weak spot along the French coast for the raiders while diversionary attacks were used to decoy the German air defensive system.

The Plan to Strike Augsburg

Bomber Command’s new chief, Air Marshal Arthur Harris, was generally opposed to small precision raids, being a strong advocate of large-scale area strikes on enemy cities. But the situation in the North Atlantic, the heavy losses of Allied shipping, compelled him to authorize the Augsburg operation. If it succeeded, it might help to reduce the number of operational U-boats while at the same time silencing critics who were clamoring for the RAF to devote more resources to hunting them.

The operation was to be carried out using six aircraft from each of No. 44 and No. 97 Squadrons, the two most experienced Lancaster units.

Starting on April 14, 1942, the squadrons carried out training operations over a three-day period, flying at low level, making 1,000-mile flights over Britain, and conducting simulated attacks on targets in northern Scotland. The work was extremely taxing, flying the heavy bombers at low altitudes in close formation while avoiding ground obstacles. But the crews were all composed of highly experienced personnel, most on their second operational tour.

Early on April 17, the crews received their mission briefing.

Speculation had been running high among the crews as to the precise nature of the target. To veteran crewmen a low-level mission signified an attack on enemy warships, a long, straight run into heavy flak. But at the briefing a map of Western Europe was marked with a long red ribbon indicating the route to Augsburg.

An Unbelievable Daylight Bombing Plan

The members of No. 44 Squadron were at first shocked and then in disbelief, while in a separate briefing the crews of No. 97 Squadron responded with a roar of laughter. No one believed that their commanders would be so stupid as to send their newest four-engine bombers all that distance inside Germany in daylight.

The six aircraft from each squadron were to proceed in two sections, each of three aircraft flying in a V-formation. The interval between each section was to be just a few seconds with visual contact to be maintained so that the sections could lend each other support if attacked by enemy fighters.

From the departure point, Selsey Bill, a headland jutting into the English Channel just east of Portsmouth, the bombers were to cross the Channel flying at approximately 50 feet, making landfall at Dives-sur-Mer on the French coast about midway between Le Havre and Caen, thus maximizing time over the Channel. While the primary group was over the Channel, a second group, under the protection of a fighter umbrella, was to make a series of diversionary attacks on Luftwaffe airfields in the Pas de Calais, Cherbourg, and Rouen areas.

After flying a short way inland, the Lancasters were to turn east and cross France and the Rhineland, reaching the Rhine River at Ludwigshafen near Mannheim, then change course southeast to make for the northern end of the Ammersee, a large lake about 20 miles south of Augsburg and just west of Munich. The planners believed that if the planes followed this route the German air defense system would think that Munich was the target. Upon reaching the Ammersee the bombers would then make a hard turn to the north toward the target.

Approaching the target the bombers were to spread out so that there was a three-mile gap between each section. The sections were to bomb from low level in formation, each Lancaster dropping four 1,000-pound bombs. The bombs were fitted with 11-second delay fuses, giving the aircraft enough time to get clear and the bombs to detonate well before the next section arrived.

With takeoff set for approximately 1500 hours and a flight time of a little over five hours, the Lancasters were to reach the target at 2015 hours, just before dusk, providing them with the protection of darkness on the homeward leg of the operation.

No. 44 Squadron Leads the Strike

The Lancasters of No. 44 Squadron were to form the first two sections of the flight. The mission leader was a 25-year-old South African, Squadron Leader John Dering Nettleton. Nettleton had joined the RAF in 1938, and in April 1942 was just completing his first operational tour, having spent much of the war to that time as an instructor.

At 1512 hours Nettleton’s Lancaster lifted off the Waddington runway, followed by six others of No. 44 Squadron. Once the formation was airborne and beginning to close up, the last Lancaster to depart, a reserve bomber, circled and returned to base. The six aircraft flew low across Lincolnshire heading south. At the front of the formation Nettleton had the aircraft of Warrant Officer G.T. Rhodes to his left and Flying Officer John Garwell to starboard. The second V, close behind, was led by Flight Lieutenant N. Sandford with Warrant Officer J. E. Beckett on the left, and Warrant Officer H.V. Crum on the right.

Ten miles to the east, at Woodhall Spa, the six Lancasters of No. 97 Squadron, led by Squadron Leader J.S. Sherwood, were also lifting off and forming up. The other five aircraft in the group were piloted by Flight Officers Hallows, R. Rodley (Wing Commander), Penman, E.A. Deverill, and Warrant Officer Mycock.

The Lancasters departed Selsey Bill on schedule. The April sky was clear, the day warm.

As the bombers hugged the waves Nettleton’s sections began to draw ahead of Sherwood’s formation, flying slightly off the intended flight path. Sherwood made no attempt to catch up; the briefing had allowed for separate attacks if circumstances decreed such, and Sherwood was highly conscious of the need to conserve fuel on such an extended sortie.

Ahead of the strike group a force of 30 Douglas Boston bombers and almost 800 fighters were busy bombing and strafing targets away from the Augsburg bombers’ planned route in the hope of drawing off Luftwaffe fighters.

No Luck for No. 44 Squadron

As the bombers approached the French shoreline the pilots lifted their planes over the coastal cliffs, roaring inland, low over the Normandy countryside. The mission planners felt that if the bombers could survive the first hour over enemy territory and if the diversionary raids could draw off German fighter units, then the Lancasters might have a good chance of reaching their target.

But maybe the planners had placed too much hope in good fortune.

The bombers were flying over wooded, hilly country near Breteuil when they encountered antiaircraft fire. Lines of tracers reached up to meet the speeding Lancasters, and black shellbursts dotted the sky around them. Shrapnel from the flak bursts ripped into two of the aircraft, but they held their course. Warrant Officer Beckett’s Lancaster was the most seriously damaged, its rear gun turret put out of action.

Whatever luck No. 44 Squadron might have had was about to run out.

As Nettleton’s six aircraft, now well ahead of the 97 Squadron formation, skirted the boundary of the Beaumont le Roger airfield, just 60 miles from the coast, they ran into trouble. As the bombers appeared a group of Messerschmitt Me-109 and Focke-Wulf FW-190 fighters of 2 Gruppe/Jagdgeschwader 2 “Richthofen,” one of the most experienced fighter units in the Luftwaffe, were returning to base after an engagement in the Cherbourg area with some of the diversionary RAF aircraft. For a moment the Lancaster crews thought they had not been spotted, but then several German fighters were seen to turn in their direction.

An Me-109 singled out Warrant Officer Crum’s Lancaster. Bullets tore through the cockpit canopy, showering Crum and his navigator, Rhodesian Alan Dedman, with razor-sharp slivers of perspex. Although blood was streaming down Crum’s face, he continued to pilot his bomber.

costly raid on the diesel engine assembly facility at Augsburg, Germany. This Lancaster was piloted

by Squadron Leader J.D. Nettleton, who led the Augsburg raid and received the Victoria Cross for heroism.

The Lancasters tightened up their formation as a swarm of Messerschmitts pounced. This was the first time that German fighters had encountered Lancasters, so they showed a certain amount of caution until they got the measure of the new bomber’s defenses. As soon as they realized that defensive armament consisted of .303-caliber machine guns, they began to press home their attacks, coming in from the port quarter and opening fire with their cannon at about 700 yards. At 400 yards, the limit of the .303’s effective range, they broke away sharply and climbed to repeat the process.

First Losses for the Lancasters

Warrant Officer Beckett was the first to go down. Near Le Tilleul-Lambert, his plane was hit by a hail of fire from Hauptmann Heine Greisert, resulting in a great ball of orange flame ballooning from a wing as cannon shells tore into a fuel tank. Seconds later the bomber was a mass of fire. Slowly, the nose went down spewing burning fragments. The shattered Lancaster then hit a clump of trees and disintegrated.

Crum’s Lancaster, its wings and fuselage already ripped and torn, came under attack by three enemy fighters. Both the mid-upper and rear gunners were wounded, and then the port wing fuel tank burst into flames. The bomber wallowed on, almost out of control, as Crum, half-blinded by the blood streaming from his face wounds, fought to hold the wings level and ordered Dedman to jettison the bombs. The 1,000-pounders dropped away, and a few moments later Crum managed to put the crippled aircraft down on her belly. The Lancaster tore across a field and came to a stop on the far side. The crew, badly shaken and bruised but otherwise unhurt, made a rapid exit from the wreckage, believing that it was about to explode into flames. But the fire in the wing went out, so, in accordance with prior instructions, Crum used an axe from the bomber’s escape kit to make holes in the fuel tanks and lit the pool of gasoline. Within minutes the aircraft was burning and reduced to a charred carcass.

Crum and his crew were eventually captured.

With Beckett and Crum gone, only Flight Lieutenant Sandford was left of No. 44’s second section. Sandford was one of the most popular officers of No. 44 Squadron. His plane was attacked by Feldwebel Bosseckert. In a desperate bid to escape, Sandford attempted to guide his bomber beneath a set of high-tension cables, but the Lancaster dug a wingtip into the ground causing it to cartwheel and then exploded, killing everyone on board.

Nettleton’s Section Escapes

The fighters now started to attack Nettleton’s section. By then they had been joined by Major Walter Oesau, a 100-victory ace who had officially been forbidden to fly more operations, but who had jumped into a fighter and taken off on first sight of the Lancasters, followed by his wing man Oberfeldwebel Edelmann. Oesau selected Rhodes’s aircraft. The Lancaster’s port engines both erupted in flames, which spread quickly to the starboard engines. Near Vieil-Evreux, Rhodes’s aircraft went into a steep climb and seemed to hang in the air on the bomber’s churning propellers for a long moment before it flipped over and dived into the ground.

There were now only two Lancasters remaining in the No. 44 Squadron formation, Nettleton and his number two, John Garwell. Both aircraft were badly shot up, and their survival seemed to be in doubt.

Then, the situation suddenly took a dramatic turn as individually or in pairs the fighters suddenly broke off and turned away, probably low on fuel or ammunition. Whatever the reason, their abrupt withdrawal meant that Nettleton and Garwell were spared, for the moment. But they still had more than 500 miles to go before they reached their target.

Flying almost wingtip to wingtip, Nettleton and Garwell swept on in their battle-scarred planes. There was no further enemy opposition, and the two pilots were free to concentrate on handling their bombers. This task grew considerably more difficult when, two hours later, they penetrated the mountainous countryside of southern Germany and the Lancasters were forced to fly through turbulent air currents.

Lancasters Reach Augsburg

In contrast to No. 44 Squadron, the flight of Squadron Leader Sherwood’s No. 97 Squadron had been generally uneventful, Frenchmen waving berets as the bombers passed overhead. Wing Commander Rodley reported that as his group proceeded south of Paris he spotted a twin-engine German Heinkel He-111 bomber. It in turn spotted the Lancasters but made a 90-degree bank and turned back toward Paris. The British bombers continued on at an altitude of 100 feet.

As the Lancasters reached the Ammersee and turned north, they climbed a few hundred feet to clear some hills and then dropped down again into the valley on the other side. There, directly ahead of them under a thin veil of haze, was Augsburg.

As they reached the outskirts of the town, a curtain of flak burst across the sky in their path. Shrapnel pummeled their wings and fuselages, but the pilots held their course. The models, photographs, and drawings they had studied at their briefing had been astonishingly accurate, and they had no difficulty locating their primary target, a T-shaped shed where the U-boat engines were manufactured.

With bomb doors open and light flak continually hitting and passing all around the Lancasters, they thundered over the last few hundred yards. The bombers jumped as their loads were released. Nettleton and Garwell were already over the northern suburbs when their bombs exploded.

The Flak Over Augsburg

In Garwell’s aircraft, a flak shell turned the interior of the fuselage into a roaring inferno. Garwell realized that this, together with the severe damage the bomber had already sustained, might cause her to break up at any moment. There was no time to gain altitude for the crew to bail out, so Garwell put the ailing aircraft down as quickly as possible. Blinded by smoke pouring into the cockpit, Garwell eased the Lancaster gently toward what he hoped was open ground. All he could do was try and hold the bomber steady as she sank.

A long, agonizing minute later the Lancaster hit the ground and skidded across a field. The plane slid to a stop, and Garwell and three members of his crew scrambled out. Two other crew members were trapped in the burning fuselage, and a third, Flight Sergeant R.J. Flux, had been thrown out on impact. Flux had wrenched open the escape hatch just before the bomber touched down, his action giving the others a few extra seconds in which to get clear, but it had cost him his life.

As Nettleton turned for home, alone now, the leading section of No. 97 Squadron bore in across the hills toward Augsburg. The target was now well marked by smoke from the initial attack, but the flak barrage was even more intense than what had greeted the two previous planes. In addition to 20mm cannon, a battery of 88mm guns, their barrels depressed to the minimum, joined in, their shells doing far more damage to the buildings of Augsburg than to the bombers. The leading three Lancasters released their loads on the target and flew on, their gunners spraying antiaircraft gun positions as they departed. The bombers were flying so low that, on occasion, they dropped below the level of the rooftops, finding some shelter from the murderous flak.

The first trio had almost made it away safely, but then Sherwood’s aircraft, probably hit by a large-caliber shell, began to stream white vapor from a fuel tank. A few moments later flames erupted from the tank. The bomber went down out of control, a mass of fire, to explode just outside the town. Sherwood alone was thrown clear and survived. The other two pilots of the section, Flying Officers Rodley and Hallows, escaped the flak and returned safely to base.

The second section, with Flight Lieutenant Penman, Flying Officer Deverill, and Warrant Officer Mycock, saw Sherwood’s plane go down as they passed over Augsburg in the gathering dusk. The sky above the town was a mass of light as the German flak gunners hurled shells into the path of the Lancasters. Mycock’s aircraft was hit and caught fire, but the pilot held doggedly on his bombing run. By the time he reached his target the Lancaster was little more than a plunging sheet of flame, but Mycock held on long enough to release his bombs. Then the Lancaster exploded, its burning wreckage cascading into the streets of the town.

Deverill’s aircraft was also badly hit, its starboard inner engine set on fire, but the crew managed to extinguish it after bombing the target and made it back to base on three engines, accompanied by Penman’s Lancaster. Both crews expected to be attacked by night fighters on the flight home, but it was uneventful. It was just as well, as every gun turret on both Lancasters was jammed.

Aftermath of the Strike on Augsburg

Nettleton eventually landed at Squire’s Gate aerodrome near Blackpool just before 0100 hours and telephoned Waddington to report on the mission and ask about survivors. On April 28, the London Gazette announced the awarding of a Victoria Cross to John Nettleton and the Distinguished Flying Cross, Distinguished Flying Medal, or Distinguished Service Order to the other survivors of the raid.

Nettleton was promoted to wing commander, and the following year he was flying his second tour of operations. On the night of July 12, 1943, he was shot down over the English Channel by a German night fighter and killed while returning from a raid on Turin.

Tragically, the sacrifice of seven Lancasters and 49 men out of the 85 crewmen that participated produced little effect. Although post-strike reconnaissance showed that the MAN assembly shop had been damaged, the full results were not known until after the war. It appeared that five of the bombs had failed to detonate. The others caused severe damage to two buildings, the forging shop and the machine tool store, but the machine tools themselves suffered only slight damage. The effect on production was negligible, especially given that MAN had five other factories building U-boat engines at the time.

Never again would the RAF send out its four-engine bombers on a daylight mission of this kind.

“An Outstanding Achievement of the Royal Air Force”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill stated: “We must plainly regard the attack of the Lancasters on the U-boat engine factory at Augsburg as an outstanding achievement of the Royal Air Force. Undeterred by heavy losses at the outset, 44 and 97 Squadrons pierced and struck a vital point with deadly precision in broad daylight. Pray convey the thanks of His Majesty’s Government to the officers and men who accomplished this memorial feat of arms in which no life was lost in vain.”

Air Marshal Harris noted: “Convey to the crews of 44 and 97 Squadrons who took part in the Augsburg raid, the following; the resounding blow which has been struck at the enemy’s submarine and tank building program will echo round the world. The full effects on his submarine campaigns cannot be immediately apparent, but nevertheless they will be enormous. The gallant adventure penetrating deep into the heart of Germany in daylight and pressed home with outstanding determination in the face of bitter and unforeseen opposition takes its place among the most courageous operations of the war. It is moreover yet another fine example of effective cooperation with the other services by striking at the very sources of the enemy effort. The officers and men who took part, those who returned and those who fell, have indeed served their country well.”

One can now only speculate on what other options the RAF might have considered for such a deadly mission.

Interestingly, Bomber Command had also taken delivery of the twin-engine De Havilland Mosquito IV Series II bomber in the spring of 1942. The first raid using the Mosquito was made with four aircraft on May 31, 1942, in a daylight attack on Cologne. The plane could outpace enemy interceptors, and, in consequence, could be sent on long flights over enemy territory to conduct pinpoint attacks with extreme accuracy. It had a maximum speed of 380 miles per hour at 17,000 feet, could carry a maximum bomb load of 4,000 pounds, and could operate at a range of 1,370 miles.

It would seem that the planners should have been aware of the Luftwaffe fighter airfields across northern France, especially along the flight path of their bombers. Rather than launching a series of diversionary attacks to draw off German fighter forces, it would have seemed prudent to send a couple of squadrons ahead of the Lancasters to sweep the point of entry and another to follow in their wake, at least as far as Paris.

The raid was notable for being the longest low-level penetration during the war as the Commonwealth pilots were brave beyond words, steady in their course, though their aircraft were badly damaged, and focused on completing their mission, whatever the cost.

Author Allyn Vannoy has written extensively on a variety of topics related to World War II. He resides in Hillsboro, Oregon.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments