by Al Hemingway

In the early morning hours of May 11, 1943, the silhouettes of two subamarines silently rose to the surface in the icy cold waters off the coast of Attu, an island in the Aleutian chain. The vessels were the USS Narwhal and the USS Nautilus, and they were carrying nearly 250 men from the Provisional Scout Battalion of the 7th Infantry Division.

Captain William H. Willoughby, leader of the group, gathered his soldiers at the rear of the sub, and they quietly inflated their rubber boats for the ride to the shore. As the subs descended, the water rose, freeing the rafts. When the pair of vessels slipped away, the infantrymen started paddling toward their objective. The Battle for Attu was about to commence.

“The Aleutians theater of the Pacific war might well be called the Theater of Military Frustration,” wrote noted military historian Samuel Eliot Morison in his now classic work History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 7. “Sailors, soldiers and aviators alike regarded the assignment to this region of almost perpetual mist and snow as little better than penal servitude.”

No truer words were spoken. The Aleutians, protruding from the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula for more than 1,000 miles, were a steppingstone to the western United States. Considered by most to be nothing more than barren, desolate countryside, their strategic value was nonexistent.

“While spared the arctic climate of the Alaskan mainland to the north, the Aleutians are constantly swept by cold winds and often engulfed in dense fog,” wrote George L. MacGarrigle in Aleutian Islands: The U.S. Army Campaign of World War II. “The weather becomes progressively worse in the western part of the chain, but all the islands are marked by craggy mountains and scant vegetation.”

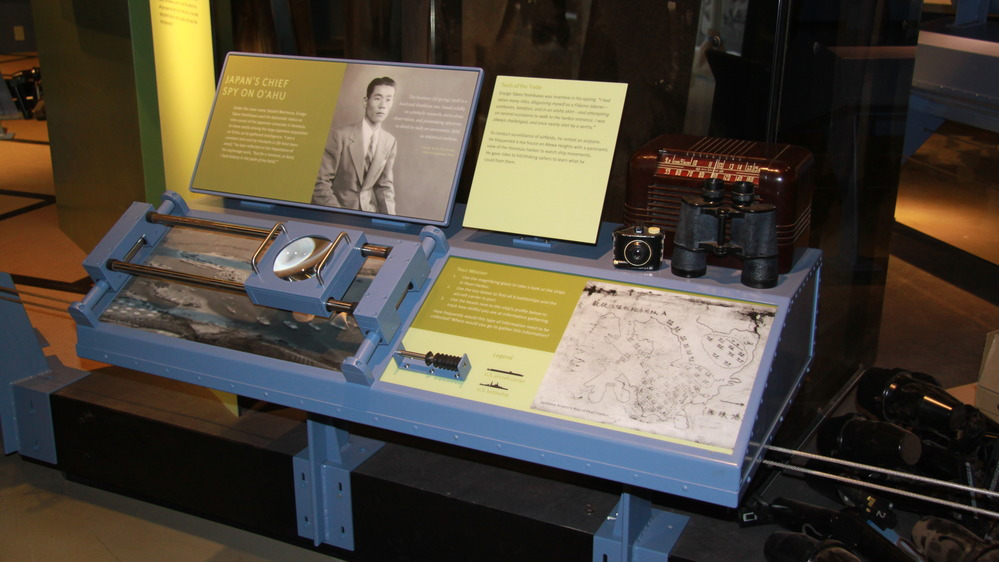

This all changed when Japan sent bombers to raid Dutch Harbor, located on Unalaska Island, in June 1942. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese fleet, decided to attack Dutch Harbor to convince the United States that the Japanese main thrust would be against America’s West Coast. He wanted to lure U.S. ships from Pearl Harbor. Then, the wily leader would strike at Midway in the Central Pacific, his real objective. Yamamoto figured the Americans would rush to defend the Aleutians. Realizing it was a feint, the U.S. Fleet would steam back to defend Pearl Harbor. Then Yamamoto would spring his trap and intercept the U.S. armada at Midway and annihilate it.

All of this elaborate planning might have succeeded if it were not for one major flaw. U.S. Naval Intelligence had broken the Japanese naval code, and the American defenders were ready to defend Midway.

U.S. Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, commander-in-chief in the Pacific, had received word of Yamamoto’s ruse in late May. Nimitz knew that Yamamoto had ordered Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya’s task force, consisting of two small aircraft carriers, five cruisers, 12 destroyers, six submarines, four troop transports, and numerous support vessels, to the Aleutians.

After the air raid on Dutch Harbor, Hosogaya was to put a force ashore on Adak Island, about 500 miles to the west. After razing the U.S. base there (the Japanese would later discover there was no military installation located there), his soldiers would come ashore on Kiska, 240 miles west of Adak, and seize the island. Additional troops would then assault Attu, almost 200 miles away, the westernmost island in the Aleutian chain.

Opting to face both Yamamoto and Hosogaya, Nimitz split his force, dispatching Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald to command Task Force 8. With his five cruisers, he was told to defend Dutch Harbor “at all costs” and stop the Japanese from moving on Alaska itself.

Yamamoto, however, had no intentions of striking at Alaska. His plan was to maintain a military presence on Attu and Kiska and keep the Americans from invading the Japanese homeland.

Likewise, the U.S. planners decided against the Aleutians as an invasion route as well. Nimitz wanted to oust the enemy from the islands and prevent any additional reinforcements from reaching Hosogaya.

Both sides, unfortunately, were saddled with the same problem: Most of the manpower and materiel was being diverted to the ongoing New Guinea and Solomon Islands campaigns.

Hosogaya’s dilemma was even worse. His supply base at Paramushiro in the Kuriles was situated 1,200 miles north of Tokyo and another 650 miles west of Attu. In addition, supplies reaching Kiska had to go nearly 400 miles farther and navigate through pea soup fog and treacherous reef-infested waters. Nevertheless, the Japanese had occupied Attu and Kiska and were in the Aleutians to stay. And it was Theobald’s job to get rid of them.

Major General Simon B. Buckner, Jr., headed the Alaskan Defense Command. He had 45,000 men at his disposal, with approximately 13,000 at Fort Randall, located at Cold Bay on the Alaskan Peninsula itself. The remainder of his troops were dispersed at Dutch Harbor and also at a newly constructed U.S. Army installation, dubbed Fort Glenn, 70 miles west of Umnak Island. Despite the seemingly large contingent of soldiers, Buckner’s command, in reality, only numbered slightly over 2,000, and some of these were engineer units sent to the Aleutians to build the new bases.

Also under Theobald’s charge was the 11th Air Force. Led by Brig. Gen. William C. Butler, it was a divided command as well. The force of 44 heavy and medium bombers and nearly 100 fighter aircraft was split between Elmendorf Airfield in Anchorage, Alaska, and other airstrips at Cold Bay and Umnak.

Although Buckner and Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, in charge of the Western Defense Command, did make a case for invading Japan utilizing the Aleutians, their real purpose was purely psychological: driving out the Japanese occupying American soil, even if that soil was as desolate as Kiska and Attu.

After Yamamoto’s disastrous defeat at Midway in early June 1942, attention shifted to the Aleutians. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) were disturbed about reports of Japanese warships operating between the Pribilof and St. Lawrence Islands. Their main concern was an invasion of Alaska itself. As a result, the Joint Chiefs recommended that Theobald and DeWitt begin planning for an amphibious assault against Kiska and Attu.

By mid-September of 1942, Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers were launched from the newly constructed airfield at Adak to attack Kiska. These repeated air assaults persuaded the Japanese that the Americans were planning to retake the islands. Troop transports began landing reinforcements at the two bases. They knew that with winter setting in the Americans would not be able to initiate a full-scale invasion until the following spring. The intolerable Aleutian weather had, once again, played a role in the strategy. And before the battle was over, it would be a decisive factor for all of those involved in the operation.

On January 11, 1943, U.S. troops slipped ashore on Amchitka Island, just 50 miles from Kiska. Although no enemy troops were stationed on Amchitka, the soldiers did do battle with the harsh elements. A willowaw, an Aleutian word for violent squall, struck the very first night. The swirling winds destroyed numerous landing craft and caused a transport vessel to run aground. If that were not enough, a blizzard started the next day and lasted for two weeks. Its howling winds, massive snowdrifts, and biting sleet lashed out at the invading force.

At the end of January, Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid presented a plan to invade Kiska, and the scheme was quickly approved by Admiral Nimitz and General DeWitt. DeWitt wanted to use the 35th Infantry Division as the assault troops commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett and Brig. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum, the assistant division commander. DeWitt felt comfortable with the unit because both Corlett and Landrum had previous service in the Aleutians, a huge plus DeWitt felt.

Kinkaid Had No Idea That His Sources Had the Enemy Troop Strength All Wrong.

The War Department, however, ignored DeWitt’s advice and tapped the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen.l Albert E. Brown, for the job. Although highly trained and motivated, the unit had been practicing maneuvers in the California desert and was being sent to North Africa to fight against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. Althoug, DeWitt and Buckner argued, their pleas fell on deaf ears. The decision of the War Department was final.

To prepare for the amphibious assault, Buckner, Nimitz, and Kinkaid sent for individuals knowledgeable in that field—people like U.S. Marine Maj. Gen.l Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith and Army Colonel William O. Eareckson. Vice Admiral Francis W. “Skinny” Rockwell would have over all command of the Kiska operation.

By the end of February, however, Kinkaid had second thoughts about invading Kiska and, instead, eyed Attu. He had intelligence that said the Japanese had only 500 defenders on the island. By hitting Attu, Kinkaid “hoped to leave Kiska high and dry surrounded by American forces.” The War Department quickly gave thumbs up to Kinkaid’s revised plan to strike at Attu instead of Kiska with the 7th Infantry Division still slated to be the assault force. The operation was dubbed Landcrab, and the invasion date was set for May 7.

What Kinkaid did not realize was that his sources had the enemy troop strength all wrong. The Japanese had approximately 2,650 men on the island equipped with mortars, automatic weapons, and some artillery. The force was commanded by Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki, who had only arrived a month earlier to take command of the garrison. The officer had no illusions. The Japanese had been badly beaten on Guadalcanal, and he was informed to expect no reinforcements, at least until the end of May. But deep inside, he knew these troops would probably never arrive either. It would be a fight to the death.

The top American planners and commanders met in San Diego to finalize the upcoming operation, and the meetings soon erupted into shouting matches between the various individuals there. DeWitt insisted that a regiment could seize Attu. Brown, meanwhile, asserted that the unforgiving environment would impede his men from moving across the island. The relationship between Brown and DeWitt was severely strained because of this disagreement. This dispute would have repercussions during the upcoming campaign.

Brown had no prior Alaska experience. He even refused Colonel Lawrence V. Castner’s recommendation to view the western Aleutians himself by air to see the layout of the islands. Another mistake was in the choice of clothing for the soldiers. The wrong boots and equipment were ordered, and these would not withstand Attu’s bone-chilling cold and wet ground. Because of the shortage of shipping, Buckner’s soldiers of the 4th Infantry Regiment had to remain on Adak. In the event Brown needed them, they would set sail for Attu within 24 hours.

By the beginning of May, the three regiments of infantry, four battalions of artillery, plus combat engineers, medical companies, and other supporting units were put aboard ships for Attu. In addition to the complement of cruisers and destroyers and the light aircraft carrier Nassau, the battleships Nevada, Idaho, and Pennsylvania were called upon to give the naval bombardment additional punch.

After much wrangling, it was decided that the Northern Attack Force, the 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment, with a battery of field artillery, would land on Red Beach a few miles north of Holtz Bay. The unit’s assignment was to drive the enemy from the western portion of Holtz Bay, take the high ground, later named Moore Ridge, and link up with the Southern Attack Force.

The larger Southern Attack Force was to go ashore on Blue and Yellow Beaches. It comprised the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 17th Infantry; the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Infantry; three batteries of 105mm howitzers; and attached support troops. The troops were to disembark at Massacre Bay and move on Jarmin Pass and Clevesy Pass (Massacre-Sarana Pass). After joining forces with the Northern Attack Force, the combined units were to drive the Japanese out of the Chichagof Harbor region, completing the seizure of Attu.

While the main landing parties were making their way inland, Captain William Willoughby’s Provisional Scout Battalion, made up of members of the 7th Scout Company and 7th Reconnaissance Troop, would land at Scarlett Beach in the Austin Cove area. Their task was to attack eastward as the main group struck at the enemy in a westward movement.

As with all things in the Aleutians, however, weather was to play a deciding factor. The morning of D-day saw a thick fog develop. Visibility was near zero. Tired of his men being cramped aboard the small transports, Colonel Frank L. Culin, commanding officer of the 32nd Infantry Regiment, commandeered several landing craft with the Aleut scouts to reconnoiter the approach to the beach. Led to shore with the assistance of the USS Phelps, a radar-equipped destroyer, the group jumped aboard several plastic dories they had towed behind them and managed to make it safely to the landing beach.

Red Beach turned out to be not much of a beach at all. It was a mere 100 yards long and encompassed by sheer 250-foot cliffs. Realizing the Japanese could ambush his soldiers with a small force, Culin told the scouts to patrol the cliffs for any signs of the enemy. Despite the concern over the possibility of a Japanese ambush, Culin ordered the assault troops to disembark. By 3 pm, he had 1,500 infantrymen ashore with no enemy activity.

The Southern Attack Force, under General Brown himself, was also hampered by the dense fog. Finally, by early afternoon, Brown decided to go ahead with the landing. At 4:20 pm, the first soldiers stepped on Massacre Beach and headed inland. The infantry quickly seized Artillery Hill where they discovered two Japanese 20mm guns. For some strange reason, the enemy troops manning the cannon had fled.

Willoughby, meanwhile, had gotten his initial group ashore, and the remainder soon followed. By late that afternoon, moving through blowing snow, the battalion had successfully made it to a crest where the soldiers could see Holtz Bay below them. Movement was kept to a snail’s pace because of the muskeg, a layer of thick, decayed vegetable matter that covered much of Attu. The slimy substance made walking slippery and treacherous at times. Setting up camp at dusk, the men ate cold rations and waited for daylight.

As with the scout battalion, muskeg was making movement miserable for the rest of the units. Brig. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold, the assistant landing force commander and the chief of artillery, soon found out that the heavy-duty sleds he had constructed for his 105mm field pieces were of no use. The guns of Battery C, 48th Field Artillery Battalion were soon mired in the unforgiving slime. Despite this, the artillerymen let loose rounds against suspected enemy mortar positions.

“During the Next Five Grueling Days, These Men Would Batter the High Ground with Constant Frontal Attacks—and Gain No Ground,”

The infantrymen of the southern attack group were also damning the terrible terrain of Attu. To make matters worse, Japanese riflemen had sprung to life and begun harassing the soldiers as they attempted to move ahead and capture the all-important Massacre-Holtz and Jarmin Passes. By evening, however, the men of the 17th Infantry had moved only a mile and a half from the beachhead. Japanese snipers situated on the high ground on the unit’s right flank forced the soldiers to scurry for cover. Colonel Edward P. Earle, leading the 17th Infantry, ordered his troops to attack straight ahead to seize the pass. Unfortunately, the enemy laid down a heavy volume of mortar and automatic weapons fire, and Earle’s inexperienced soldiers withdrew. After another unsuccessful attempt at a frontal assault, Earle pulled his forces back and established a perimeter.

This inaction would prove costly. “During the next five grueling days, these men would batter the high ground with constant frontal attacks—and gain no ground,” wrote military historian Brian Garfield in his book The Thousand Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians. “Japanese entrenchments dominated all approaches; the Americans had to cross open slopes with no cover at all. The Japanese guns were linked along the summits, at the military crest a few feet below the skyline. Fog hid the Japanese, while it revealed the American lines; and even when the fog thinned, the Japanese used smokeless powder which couldn’t be seen.”

In spite of the delay and confusion in the landing, Massacre Bay was in American hands with 1,500 soldiers ashore near Holtz Bay and another 400 of Willoughby’s scout battalion encamped in the snow-covered mountains. The impossible and erratic weather of the Aleutians would play a huge part in the upcoming battle, not only in compounding the difficulty for the Americans in securing their objectives on the island but also in making it extremely difficult to get supplies to the advancing infantry.

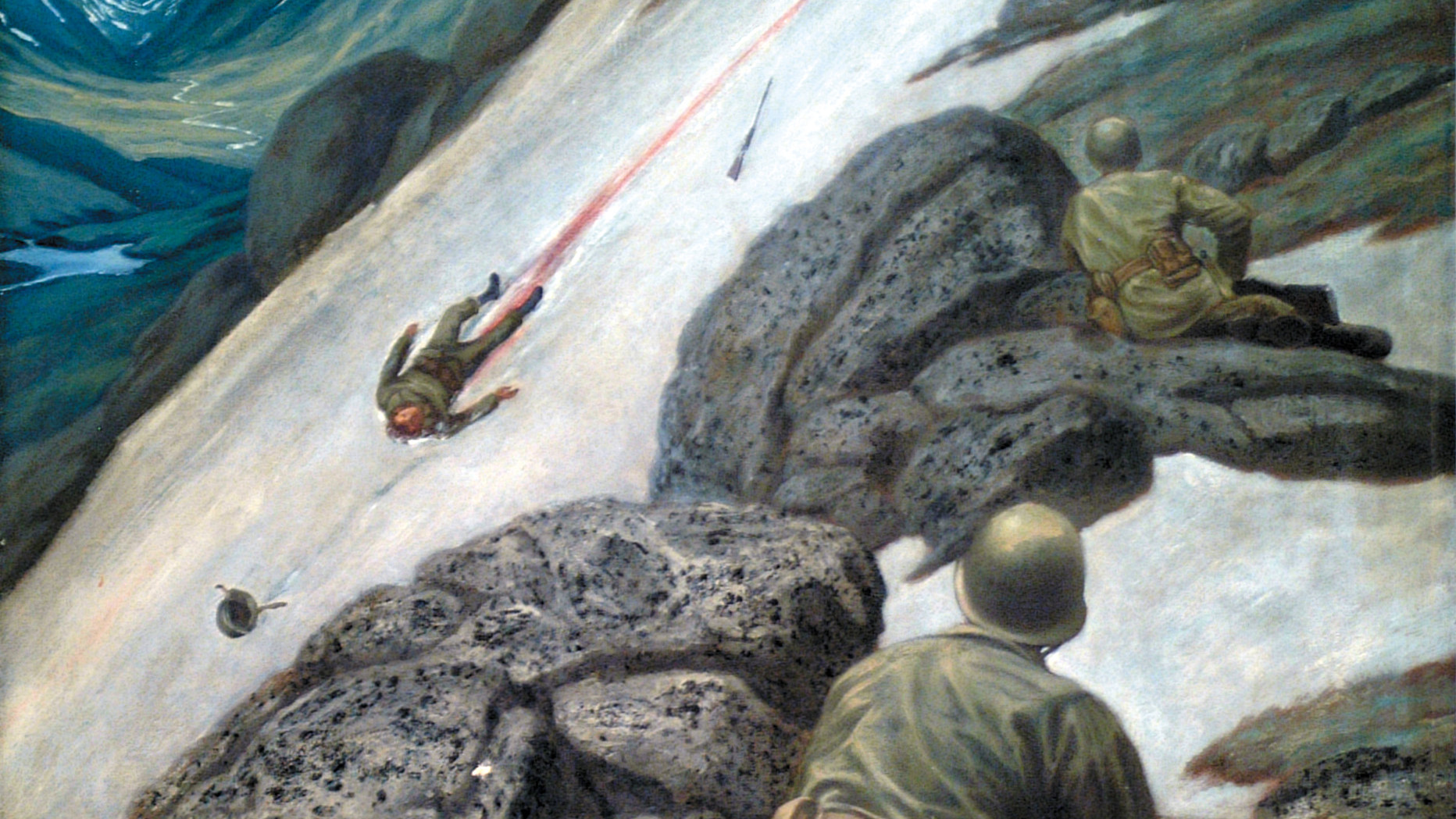

The following day, D+1, saw Earle’s Southern Force still bogged down. When his radio malfunctioned, he decided to do a personal reconnaissance of his lines. Some time later, Earle’s lifeless body was discovered, the apparent target of a Japanese sniper. Next to him was the wounded Alaskan scout who had gone with him. Colonel Wayne C. Zimmerman took charge of the 17th Infantry. Willoughby’s men continued their advance in the morning toward the Japanese rear. Movement was not easy as the soldiers were forced to slide down the sheer, icy slopes “like human toboggans.” Soon, they were embroiled in a hot firefight, but the battalion’s 81mm mortar crews halted the enemy attack. Willoughby’s troops kept up the pressure on the Japanese while the Northern Force attacked the Holtz Bay area.

By early evening, the 17th Infantry had pushed the enemy back, only to be hit with a savage counterassault. Grenades were tossed at close range, and Japanese soldiers rushed the American positions. Men were bayoneted and shot before they could signal for help. One soldier was thrown in the air from the concussion of a grenade blast, losing his boots in the process.

Sergeant Frank J. Gonzales of Company B, 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry became engaged in a bayonet duel with a charging enemy soldier. Gonzales killed him with a thrust to his midsection. As he tried to retrieve his bayonet, however, he could not remove the blade from the body. Gonzales twisted and turned and even discharged his weapon into the motionless Japanese soldier but was still unsuccessful in getting it out. Disgusted, he finally unsnapped the bayonet and left it in the body as he ran to rejoin his unit.

The infantrymen managed to hold their ground and moved over the crest of a ridge. “We counted between forty to fifty dead Japs, two of them officers, and captured seven machine guns,” Gonzales later recounted in The Capture of Attu: As Told by the Men Who Fought There by Liutenant. Robert J. Mitchell, a wounded veteran of the battle. “One Jap gunner was slumped over his gun and his blood was running down and dripping off the end of the barrel. It made me feel good to see him.”

The next day, Colonel Eareckson bravely flew into Attu’s soupy fog to try and reconnoiter Japanese positions so his bombers could assist the infantry. The unforgiving weather of the Aleutians, unfortunately, did not help, and Eareckson could not see anything below.

Colonel Zimmerman, meanwhile, sent his men into Jarmin Pass to seize it. A murderous crossfire prevented them from accomplishing their mission. The enemy troops had cleverly concealed themselves on Black Mountain, a hill that divided Jarmin Pass from Zwinge Pass. The wily Japanese had fighting holes dotted throughout the area on Robinson Ridge and Cold Mountain on the right flank and Henderson Ridge on the left flank.

For the next five days, Zimmerman’s men clawed their way forward. Elements of the 32nd Infantry and the 4th Infantry arrived to bolster Zimmerman’s forces. The fighting was close and bloody as the soldiers slowly inched their way into Jarmin Pass to cries of “You Die American Dog!” as their Japanese counterparts harassed them every step of the way.

The Northern Force, trying to link up with Zimmerman’s southern troops, was moving rapidly through Holtz Bay. The infantrymen soon captured the Japanese positions in the valley above Holtz Bay. It appeared that the enemy had retreated to another ridge across from the bay and abandoned ammunition, food, and weapons to the advancing Americans. Colonel Frank Culin, commanding officer of the force, opted to push ahead to oust the Japanese from the ridge and move toward Chichagof Bay. This “wedge” would take the pressure off the enemy units above Jarmin Pass and perhaps they would pull back toward Chichagof Harbor where they would be surrounded as the Americans wanted from the start.

Willoughby’s beleaguered force, meanwhile, had battled the Japanese in continuous firefights. The bitter weather had taken its toll; nearly half of the unit had succumbed to frozen feet and frostbite. The Scout Battalion had to keep moving forward, Willoughby realized, because there was no retreat. Attack was his only recourse. Even the enemy grudgingly respected the American fortitude, as evidenced by one Japanese officer’s diary entry: “Enemy strength must be a division.”

General Brown was Shocked to Discover That He was to be Relieved of Command

Miraculously, the Scout Battalion held and performed magnificently. Later, Captain Willoughby would write, “Since we couldn’t sleep at night, we weren’t about to let the enemy sleep. We kept up a din around the clock so that they wouldn’t divert any forces away from us against Culin. Finally, when the time looked right, I told Colonel Culin by radio that we were moving down, and we headed down towards Holtz Bay. The enemy was pulling out fast.”

General DeWitt, meanwhile, was extremely dissatisfied with General Brown’s conduct ashore. He continuously requested additional supplies and reinforcements, which irritated DeWitt who had not liked Brown since their initial meetings at the planning stage of the operation. In all fairness to Brown, DeWitt had gone out on a limb and promised the Joint Chiefs that Attu’s defenses would crumble in just three days. The lack of communication also was a disadvantage to Brown. DeWitt, Buckner, and Kinkaid were all on Adak, hundreds of miles away, and did not possess firsthand knowledge of what was transpiring on Attu.

Despite this, DeWitt requested that Brown be relieved of command. DeWitt and Buckner met with Kinkaid, the overall commander of the operation. After listening to both of them, he acquiesced. He sent a telegram to Brown informing him that recently promoted Maj. Gen. Eugene Landrum was taking over. Shocked, Brown nonetheless followed orders and turned his unit over to Landrum. For years, he felt he had been made the scapegoat because of DeWitt’s assurance of a quick victory.

On May 17, Culin’s men readied themselves for an all-out assault on the ridge overlooking Holtz Bay. Just past noon, the infantrymen charged up the slope. Preceding their advance was the artillery. As the rounds impacted to their front, the soldiers made their way to the summit. They soon discovered the enemy had fled, and they seized the position without a fight. The following day, Lieutenant Morris C. Wiberg and three soldiers of Company K, 3rd Battalion, 17th Infantry met up with a patrol from the 7th Reconnaissance Troop. The two forces were finally joined together.

With the seizure of Jarmin Pass and the Holtz Bay area, all attention now turned to Chichagof Bay. On May 21, the 3rd Battalion, 17th Infantry moved on Sarana Nose. Although badly dazed and shaken, the Japanese put up a fight but were quickly overrun, and the objective was secured.

The attack resumed as a light snow fell on Sunday, May 23. Several companies from the 4th Infantry soon became trapped by enemy machine guns as they tried to push forward. Disgusted by the delay, Private Fred M. Barnett grabbed some grenades and his M-1 Garand and proceeded uphill toward the Japanese positions. Soon, the distinct sound of explosions, machine-gun bursts, and rifle fire permeated the air. Then, as quickly as it started, it suddenly ended and there was an eerie silence. Then through the thick fog, Barnett emerged and motioned everyone to move forward. As they approached the enemy machine-gun emplacements, they saw that Barnett had successfully eliminated all nine of them without being wounded.

At 10 the following morning, American troops attacked Fish Hook Ridge to isolate the remainder of Yamasaki’s force. The going was arduous as the men had to endure terrible terrain and a fanatical enemy. Every crevice and cave had to be searched. Soldiers lobbed in grenades before entering any opening. The orders were simple and direct: “If they don’t stink, stick ’em.”

Soldiers on the front lines had to withstand bitter cold temperatures without the benefit of any shelter. The sick and missing soon began to multiply. To support the infantry, Landrum had every available howitzer manhandled from the beach to a crest overlooking the Fish Hook; even the artillery rounds had to be carried up the ridge by the artillerymen.

Once again, the weary troopers of the 4th Infantry struck at the Fish Hook on May 25. Hidden behind snowdrifts and boulders, the enemy opened fire, trapping the soldiers in a vicious crossfire. By nightfall, the exhausted men had managed to clear the Japanese from their trenches and even secured the base of the ridge.

A miracle occurred the next day—the sun appeared through the fog that had enveloped Attu for the past two weeks. With the weather improving, dozens of Army Air Corps planes bombed and strafed the main enemy installation at Chichagof Harbor. One Japanese officer penned in his dairy, “Am suffering from diarrhea and feel dizzy … It felt like the barracks blew up, things shook up and rocks and mud flew all around and fell down; strafing planes hit the next room; my room looks like an awful mess from the sand and pebbles that come down from the roof. Consciousness becomes insane. There is no hope of reinforcement. Will die for the cause of the Imperial Edict.”

“He Stood There it Seemed Like an Hour Exposed Wide Open and Loaded and Fired Until the Magazine was Empty.”

With a break in the weather, the battle-hardened soldiers struck at the Fish Hook again. When K Company, 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry was delayed by Japanese machine gunners, Pfc. Joe P. Martinez began advancing at the enemy positions firing his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), killing five Japanese defenders.

“He stood there it seemed like an hour,” recalled one eyewitness, “exposed wide open and loaded and fired until the magazine was empty. He loaded two or three times and then we heard it, a kind of crack and thoomp! Martinez fell backwards towards us.” The New Mexico native had sustained a serious head wound that would prove fatal. For his extraordinary bravery, Martinez would be Attu’s sole Medal of Honor recipient.

By May 27 most of the Fish Hook was in U.S. hands. The infantry now could see Buffalo Ridge—the last remaining Japanese stronghold on Attu. It was a matter of several hundred yards, and the enemy resistance on the island would be broken and the battle over. Yamasaki had only 800 troops left from his original contingent of 2,650. He knew no additional troops were coming. Surrender was out of the question; the Bushido Code of the Japanese soldier forbade such an action. He had two options, as he saw it: wait for the inevitable assault and kill as many Americans as possible—or attack. He chose the latter.

Yamasaki prepared his men for the final Banzai. He would strike the Americans at the weakest part of their perimeter—the point between the Buffalo and the Fish Hook. He would hit them at night when they would be most vulnerable. His men would charge up Engineer Hill, where the Americans stored their artillery, ammunition, and food, and capture it. He would then take as much of the captured supplies with him as possible, destroying the rest, and turn the enemy’s own 105mm cannon on them as well.

In the predawn hours of May 29, Yamasaki gathered his men and quietly marched up the valley floor. After killing several American guards, he moved through the perimeter without being detected.

At 3:30 am, the terrifying cry of “Banzai!” filled the cold night air as Yamasaki’s band surged ahead, running into Company B, 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry, which was coming off the front lines for a much deserved hot breakfast. The soldiers ran as the enemy pushed ahead to their objective. Yamasaki’s men slashed and bayoneted their way through the thinly held line. Wounded men were killed where they lay. Others faked death and survived the onslaught.

The noise soon alerted the units defending Engineer Hill. Calmly, Brig. Gen. Archibald V. Arnold organized a provisional force from the 13th and 50th Engineers, the 7th Medical Battalion, the 20th Field Headquarters, and a few frostbitten soldiers from the 4th Infantry being treated there.

Creating a defensive perimeter, Arnold had his men toss hand grenades at the charging mass of Japanese moving up the hill. A 37mm gun was swung into action. The combination of the small arms fire, hand grenades, and 37mm shells tore into the enemy’s ranks. When the Japanese survivors managed to climb to the crest, they encountered bayonets and rifles. Bloody fighting ensued, and the assault petered out as the enemy left the hill and melted into the night.

Several additional attempts were made to seize Engineer Hill by Yamasaki’s men, but they resulted in failure. Hundreds of enemy troops committed suicide after the attack was beaten back. Later that morning, Colonel Yamasaki was also killed leading a futile charge against the American perimeter.

With the exception of mopping-up action, the fight for Attu was finished. The Americans sustained 3,829 casualties: 549 killed, 1,148 wounded, 1,200 frostbite victims, 614 from sickness and exposure to the cold weather, and 318 as a result of suicide, combat fatigue, and accidents. The Japanese were virtually annihilated, with only 28 surrendering to U.S. forces.

Attu would prove to be beneficial for future planners. U.S. Army troops had successfully completed their first amphibious assault. Also, cold weather combat was closely studied. Medical personnel examined veterans of the fighting to avoid future errors. Clothing and supplies received top priority for upcoming cold weather operations.

The movement of Japanese forces from Truk in the Caroline Islands in an attempt to evacuate Attu and Kiska’s defenders siphoned ships and troops away from other Pacific fighting. This left Rendova, in the Central Solomons, largely undefended, and the island was taken with ease in June. Clearly, the capture of Attu reaped huge benefits for the United States.

Despite these rewards, the Attu campaign received scant attention in the U.S. newspapers. One veteran remarked sarcastically, “No Marines—-otherwise it would have been world history.”

The Army and Navy were humiliated by the costly mistakes committed during the campaign and did not want to face public scrutiny. The sacrifices made by the brave soldiers were “played down by the ministries of war propaganda.”

The combat on Attu was unforgiving and brutal. As historian Brian Garfield wrote: “The price of weatherbeaten Attu had been high. In proportion to the number of troops engaged, it would rank as the second most costly American battle in the Pacific Theater—second only to Iwo Jima.”

Al Hemingway is a Marine Corps veteran of the war in Vietnam. He has written extensively on World War II in both the the Pacific and European Theaters.

My father fought on Attu,& this narritive could’ve been written by him. That is how closely this is to what i could get out of him on his experiences in the Alutians. He is gone now,but as much as i miss him,i realize his & his commerades contributions to the war effort,though ignored by media,did aid the U.S. in their war against tyrany.

In the last years there have been more and more articles and books written about the Forgotten War in Attu and the Aleutians. This article with map and photos is one of the best, most concise and understandable reads.

My father would never tell us what his role in this part of the war entailed, so I have been trying to research into what really happened.

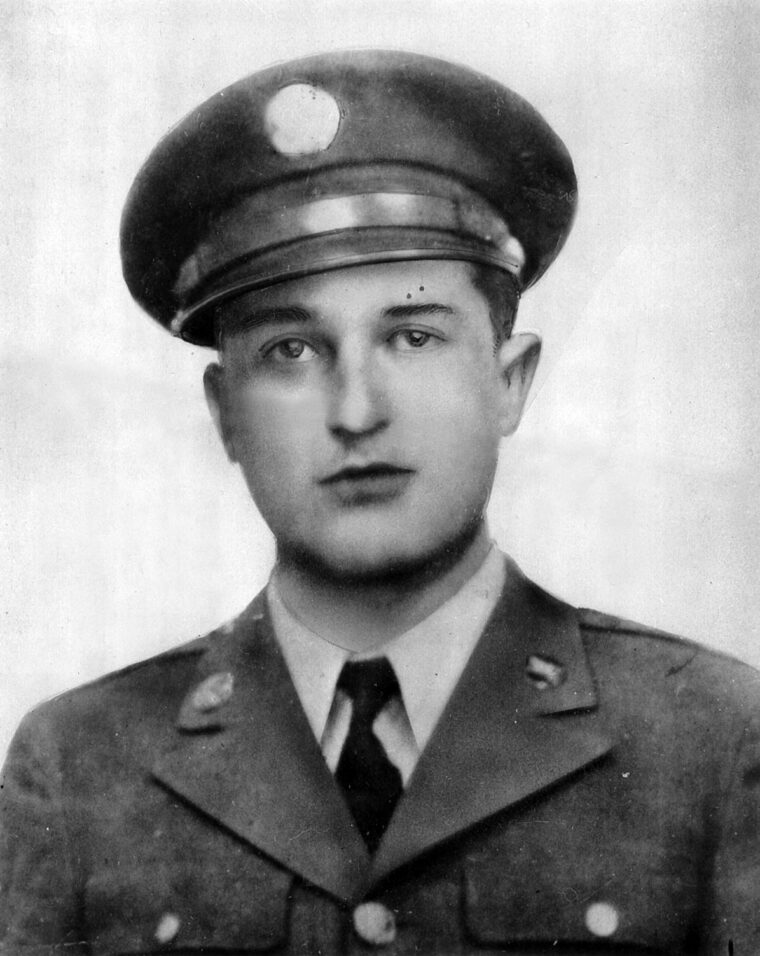

Albert Leon Levorson, was an active member of Castner’s Cutthroats (Alaska Scouts). He won a long-delayed Bronze Star for his heroic efforts there (awarded in 1951). For me, the role of the Scouts was the only element missing in this article, but then I’m a bit prejudiced?

Thank you Mr Hemingway and Warfare History Network!