By Victor Kamenir

After crushing the first-line Soviet armies in brutal three-week cauldron battles at the border, the steamroller of German Army Group Center continued deeper into Soviet territory during the opening days of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, which began on June 22, 1941.

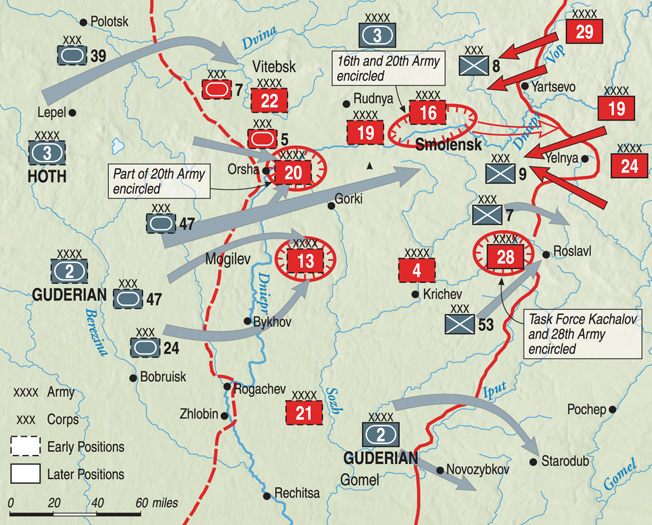

The twin armored spearheads of Army Group Center were Panzer Group 2 under the command of General Heinz Guderian and Panzer Group 3 under extremely capable tank general Hermann Hoth. Their coordinated offensive on July 10, 1941, unleashed the Battle of Smolensk, a bloody struggle around the ancient Russian city that was to last two long months.

The Smolensk Gate: Land Bridge to Moscow

The city of Smolensk, long famous for its multitude of churches, occupied a strategically valuable “land bridge” on the way to Moscow. Known as the “Smolensk Gates” in Russia, the 45-mile wide neck of land between the headwaters of the Dvina and Dniepr Rivers was the traditional invasion route from central Europe into the heart of Russia. This road had been taken in the 17th century by the Polish Army, resulting in the capture of Moscow. In 1812, Napoleon fought a battle at Smolensk, burning the city to the ground.

Now, this region of fertile agricultural land was once again the stage for a titanic struggle. Still reeling from its earlier unexpected defeats, the Soviet high command hurriedly deployed a string of armies to protect this vital sector of the front. It was imperative to hold Smolensk at all costs, buying the Soviet leadership time to mobilize and deploy new armies for the defense of Moscow.

To stem the tide of disasters, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin instituted draconian measures. On June 30, General Dmitriy M. Pavlov, whose Western Army Front was crushed by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center, was recalled to Moscow. Served up by Stalin as a convenient senior scapegoat for the series of disastrous defeats, Pavlov was relieved of command, court-martialed along with several of his senior deputies, and executed, according to various sources, sometime between July and September 1941.

In his stead, on July 2, Stalin dispatched the top Red Army commander, Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko, to take charge of the Western Front. Timoshenko’s reconstituted Western Front was created from second-echelon armies belonging to reserves of the high command. Spread out along almost 400 miles of front, from Idritsa in the north to Rechitsa in the south, were the Twenty-Second, Twentieth, Thirteenth, and Twenty-First Armies. Survivors of the Fourth Army, which had conducted a fighting retreat from the border, were being rallied and reorganized behind the Thirteenth Army in the area of Krichev.

Another two armies allocated to Timoshenko’s command, the Sixteenth and Nineteenth, were moving up from the Ukraine by train and were disembarking at various railroad stations around Smolensk just as the Germans launched their offensive. However, the move from the Ukraine was a difficult one, conducted in a chaotic atmosphere of poor coordination, gigantic traffic snarls at railroad stations, and punishing German air attacks. As a result, many trainloads of troops and equipment arrived in the wrong locations, some rerouted far to the east owing to damaged railroad tracks. Some units disembarked without their leadership and equipment, and some headquarters arrived without troops to command.

Conflicting Strategies in the German Camp

Both sides were racing against the clock. The Soviet command was rushing forward newly created units as soon as they were mobilized, very often practically untrained and poorly armed and equipped. Lacking reserves and having an extensive front to cover, the Soviet armies were deployed in one echelon, without any significant defenses in depth. Most Soviet rifle divisions held front lines of up to 15 miles, more than double what was called for in prewar planning.

The majority of Timoshenko’s forward rifle divisions were desperately short of specialized equipment such as radio and telephone sets, antitank artillery, transportation, and rear support services units. The drubbing that the Red Air Force received in the opening stages of the campaign and the lack of sufficient air defense artillery allowed the Luftwaffe to operate above the battlefield with virtual impunity. Most of the Red Army’s mechanized assets were destroyed in earlier fighting, and tanks were in short supply to contain breakthroughs or to follow up counterattacks.

At the same time, a struggle over the character of ongoing operations was taking place within the German high command. Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler was preoccupied with the idea of not allowing the surrounded Red Army forces close to the border in the Byelostok and Minsk pockets to escape. He was demanding that the hard-charging panzer generals like Guderian and Hoth slow down, allowing infantry units to catch up and form a tight double ring around the surrounded Soviet troops. Further, during the first week of July Hitler began talking about halting the eastward advance once the vicinity of Smolensk had been reached and turning the panzers of Army Group Center north toward Leningrad and south into the Ukraine.

Another faction was strongly advocating continuing the rapid push to Moscow. Colonel General Franz Halder, chief of the German General Staff, while overtly paying lip service to Hitler’s plans, tacitly encouraged carrying on the offensive. In his war diary, Halder wrote on June 29: “Let us hope that commanding generals of corps and armies will do the right thing even without express order, which we are not allowed to issue because of the Führer’s instructions to Army High Command.”

Guderian, in his turn, clearly saw that speed was of the essence: “It would be some 14 days before our infantry could arrive on the scene. By that time the Russian defenses would be considerably stronger. Whether the infantry would then be able to smash a well-organized river defensive line so that mobile warfare might once again be possible seemed doubtful.… I was so convinced of the vital importance and of the feasibility of the task assigned me, and at the same time so sure of the proved ability and attacking strength of my panzer corps, that I ordered an immediate attack across the Dniepr and a continuation of the advance toward Smolensk.” General Hoth was also in support of continuing the drive on Smolensk.

Stretched Supply Lines

Planning his attack against Smolensk, Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, in overall command of both panzer groups, intended to fracture the Soviet Western Front and annihilate the bulk of its forces in familiar cauldron battles. The northern sector of von Kluge’s area of operations was characterized by extensive marshlands, small rivers, and wooded terrain not favorable for panzer operations; therefore, the emphasis would be toward the south, where more open terrain was well suited for far-ranging panzer maneuvers. The epicenter of the German attack was concentrated against the area of the Vitebsk–Orsha–Mogilev line.

The capture of Smolensk called for a typical pincer movement, skirting the city from north and south and linking up east of it, in the Yartsevo–Yelnya area. The XXXIX Motorized Corps, belonging to Hoth’s Panzer Group 3, was to strike from Vitebsk to Demidov and, from there to Yartsevo. The XLVII Motorized Corps from Guderian’s Panzer Group 2 was to attack from Tolochin, where Napoleon had his headquarters in 1812, to Orsha and then to Yelnya. Advancing on the right flank of Guderian’s group, his XLVI and XXIV Motorized Corps were to form a smaller pocket around Mogilev and then push southeast to Roslaval.

The weakness of the German plans lay in the fact that supply lines were getting seriously overstretched and the supporting infantry armies marching on foot, the Ninth Field Army for Hoth and Second Field Army for Guderian, were over 60 miles behind their fast-moving mechanized brethren. This would soon play a significant role, allowing many of the Soviet units bypassed by German motorized corps to slip away to the east.

Controlling the Soviet Panic

German plans were slightly delayed when on July 6 Timoshenko launched a determined attack against Panzer Group 3 from the Vitebsk area toward Lepel, utilizing the V and VII Mechanized Corps. However, the poorly coordinated Soviet attack went in with virtually no reconnaissance and ran into prepared German antitank positions. During the grinding three-day battle, the two Red Army mechanized corps were savaged in large part by a combination of vicious Luftwaffe air attacks and the direct fire of antitank artillery. Counterattacking the reeling Soviet formations on July 9, Hoth’s 7th and 18th Panzer Divisions punched a hole between the Soviet Twentieth and Twenty-Second Armies and captured Vitbesk.

Timoshenko, lacking ready reserves to plug the gap between the two armies, was forced to commit the closest units of the 19th Army, without their having a chance to reorganize after a difficult move from the Ukraine. On July 10, Lt. Gen. Ivan Konev, commander of the Nineteenth Army, counterattacked with two available divisions, the 220th Motorized Rifle and 162nd Rifle. The 220th, despite being composed largely of barely trained recruits, conducted itself well and even fought to the east side of Vitebsk. However, it sustained prohibitive losses on its first day of combat, with one of its regimental commanders killed.

The 162nd Rifle Division fared much worse, initially making some progress, but falling back very soon. Maj. Gen. Aleksandr V. Gorbatov, deputy commander of the XXV Rifle Corps, approached Vitebsk and encountered groups of Red Army soldiers streaming eastward in disorder. Gorbatov and his staff officers were able to halt groups of retreating men and begin digging astride the Vitebsk–Smolensk road. Leaving behind several of his officers to continue rounding up and reorganizing stragglers, General Gorbatov rushed to the original positions of the retreating 501st Rifle Regiment, less than two miles to the west. To his horror, Gorbatov found the positions completely abandoned, save for three men. One of them was the regimental commander, a Colonel Kostevich, accompanied by his chief of staff and a corporal serving as a radio operator.

Gorbatov later wrote, “When I asked the regimental commander: ‘How did you manage to get to this situation?’—he, helplessly motioning with his arms, replied: ‘I understand the gravity of what happened, but could not do anything; therefore, we decided to die here, but not to retreat without orders.’ There were two Orders of the Red Banner on his chest. But, recently called up from reserve, he spent many years out of the army and, apparently, completely lost leadership skills. True, he was quite capable of dying without abandoning his post. But who would benefit from that? It was embarrassing to look at his pathetic appearance.

While realizing that returning the regiment to its previous positions was out of the question, I invited the officers to come with me, loaded them up in [my] car and took [them] to the regiment. I pointed out to Kostevich a position for his observation post, advised him how to best deploy his battalions and fire support assets … In the woods, to the right of the highway, I found the corps’ artillery regiment and discovered that its guns did not have prepared firing positions and commanders of the regiment and [its battalions] did not have observation posts.”

Unfortunately, the panic was beginning to spread through many units of the Twentieth and Twenty-Second Armies. Lt. Gen. Konev discovered complete chaos near Rudnya, a small town between Vitebsk and Smolensk: “A disorganized stream was moving toward us—vehicles, wagons, horses, columns of refugees with many soldiers among them. Everyone was in a hurry toward Smolensk. It was absolutely impossible for us to drive to Vitebsk. The road was completely choked. I decided to [use my] staff officers to put the things on the road in order, gave instructions to stop all military personnel, form up infantry units, separate artillerymen, tankers and send everybody back to Vitebsk. To my surprise, even tanks were moving from Vitebsk to Rudnya—several heavy KVs and several T-26s. Especially strange was to see the retreating new tanks. Three KV tanks were moving to Rudnya, allegedly for repairs. Literally threatening them with guns, sticking revolvers into drivers’ hatches, we stopped these tanks, which, by the way, turned out to be operational; we took them under control. In this manner we managed to collect by evening almost a battalion of infantry, a battery of 85mm air defense guns, and a battery of 122mm guns.”

Orsha and Mogilev Encircled

Despite the best efforts of senior Soviet officers, during the next several days, Hoth’s divisions steadily pushed the Nineteenth Army east and encircled the right flank of the Sixteenth and Twentieth Armies north and west of Smolensk. On the same day, Guderian’s XLVII Motorized Corps, skirting the city to the south, came close to linking up with the northern pincer and completely surrounding the two Soviet armies. The beleaguered Nineteenth Army and survivors of V and VII Mechanized Corps barely managed to hang on to one Dniepr River crossing near Solovyevo village, approximately 10 miles south of Yartsevo, holding open a lifeline to their comrades at Smolensk.

Launching his attack across the Dniepr River on July 10, General Guderian established several vital bridgeheads on the east bank, striking at the junction of the Soviet Twentieth and Thirteenth Armies south of Orsha and prying apart the flanks of both armies.

A bitter fight flared up for Orsha, defended by units from the Soviet Twentieth Army. Especially distinguishing themselves were the 73rd Rifle Division under Colonel A.I. Akimov and 1st Proletarian Motorized Rifle Division under Colonel Yakov G. Kreitzer. This latter division initially belonged to the VII Mechanized Corps but was diverted south prior to VII Corps’ ill-fated attack and was spared destruction along with its parent unit. The 1st Proletarian Division, stationed in one of Moscow’s suburbs, was the Red Army’s showpiece and experimental unit. It was constantly kept at near full strength and was usually given new equipment and tactics to test. Colonel Kreitzer served almost his entire career in this unit, progressing from platoon leader to division commander and, unlike many of his fellow officers, enjoying the complete trust and confidence of his men.

As a curious side note, many well-known Moscow athletes were sent to this division upon mobilization. In addition, Lieutenant Rueben Ibarruri, son of exiled Spanish Communist leader Dolores Ibarruri, served in this unit until being wounded in subsequent fighting.

On July 11, as Colonel Kreitzer was preparing his division for a counterattack the next day, he was seriously wounded in his right arm during an air attack and taken to the rear. The next day, before Kreitzer’s division had a chance to attack, its neighboring LXIX Rifle Corps was hit hard by combined German air and panzer attacks and withdrew, jeopardizing the flank of the Moscow division. Despite the best efforts of its defenders, Orsha was completely surrounded on July 14.

After holding the defenses of Orsha for several days, the units trapped within the small pocket, spearheaded by the 1st Proletarian Motorized Division, fought their way clear before the German ring had a chance to solidify. Unable to retreat east, survivors of the division, now numbering only 1,500 men plus some from the LXIX Rifle Corps, turned south and joined the defenders of Mogilev, also surrounded.

Mogilev, encircled since July 12, was held by parts of the Soviet Thirteenth Army, in particular the LXI Rifle Corps under Maj. Gen. F.A. Bakunin. Attempting to relieve pressure on Mogilev, the Twenty-First Army launched an attack on July 13 led by its LXIII Rifle Corps under Lt. Gen. Leonid G. Petrovskiy. In a spirited advance, Petrovskiy’s men crossed to the west side of the Dniepr River, recaptured Rogachev and Zhlobin, which had been lost on July 9, and continued moving to Bobruisk. The German command had to shift valuable reserves to slow the Soviet offensive. Even though much pressure was taken off Mogilev’s defenders, the LXI and LXIII Corps could not link up and Bakunin’s command remained trapped inside Mogilev.

On July 27, survivors of the LXI Rifle Corps and the 1st Proletarian Division fought their way out of the encirclement and linked up with the main Soviet forces. Not all the Red Army men were able to make it out of Mogilev. Some stragglers became stranded in the city when the last bridge was destroyed by their retreating comrades. Surrounded Soviet soldiers fought for another day before being hunted down among the ruins, killed or taken prisoner. Colonel Yakov Kreitzer soon rejoined his men, and the 1st Proletarian Division was rebuilt with new soldiers and proud traditions. Colonel Kreitzer himself survived the war and rose to high rank in the Red Army.

When Guderian struck at the junction of the Soviet Twentieth and Thirteenth Armies on July 10, his attack was so determined that it pushed the bulk of Lt. Gen. P.A. Kurochkin’s Twentieth Army to the northeast of Orsha and to the north side of the Dniepr River. While the panzers bypassed Smolensk on the way to Yartsevo, elements of the 29th Motorized Division broke into Smolensk from the south and began digging out the stubborn defenders block by block. The German attack was executed with such speed that Soviet commanders did not have a chance to organize proper defenses of the city.

Capturing Smolensk and Stalin’s Son

The city of Smolensk is divided roughly in half by the Dniepr River, which flows east to west in this area. By nightfall on July 15, the Germans were in possession of the southern part of the city. As the bulk of the city’s defenders, mainly from the Sixteenth Army, retreated to the north side of the river, the commander of Smolensk garrison, Colonel P.F. Malyshev, ordered the inter-city bridges blown up.

The commander of the Sixteenth Army, Lt. Gen. Mikhail F. Lukin, began frantically organizing defenses on the north side of the river. With the war less than four weeks old, Lukin had already distinguished himself as a skilled commander. When the war started, Lukin’s army was in the process of being transferred by train to the Ukraine from a Siberian military district. As his first trainloads began unloading at Shepetovka, Lukin, like Konev, received orders to divert his army north into Belarus, where the Soviet forces of the Western Front were being crushed.

However, an unexpected breakthrough by German Army Group South at Ostrog threatened Shepetovka, a vital railroad center and site of a major Red Army supply and ammunition depot. As the senior commander on the scene, Lukin hurriedly put together a scratch force consisting of parts of two of his divisions and whatever other units he could find. He held the line for several desperately needed days until a rifle corps relieved him.

Now, as Smolensk burned around him, Lukin ordered his men to occupy positions at the water’s edge to discourage German attempts to cross the river during the night and establish beachheads. Lukin’s attempts to shift his troops from the northern edge of the city to the river were hampered by having to navigate the city streets amid burning buildings and German shelling. It was too late. On the morning of July 16, the Germans renewed the attack, and even though Lukin’s men fought tenaciously the German 29th Motorized Division was in complete possession of Smolensk by that evening.

Also on this day, Senior Lieutenant Yakov Dzhugashvili, commander of an artillery battery in the VII Mechanized Corps, was captured east of Vitebsk. Yakov was Stalin’s son by his first wife, Ekaterina Svanidze, who died in 1907 from tuberculosis. Yakov and Stalin did not get along well, with Yakov often bearing the brunt of Stalin’s insults and angry tirades. Later in the war the Germans proposed to exchange Yakov for Field Marshal Freidrich Paulus, captured at Stalingrad in 1943. Stalin turned down the offer, allegedly stating: “I do not trade lieutenants for field marshals.” Shortly thereafter, Yakov committed suicide in a POW camp by charging the wire. He was shot dead by a German guard.

The Counterattack at Smolensk

Hearing of the loss of Smolensk, Stalin flew into a rage, accusing Marshal Timoshenko and his staff of cowardice and defeatist spirit. The specter of the fate of Col. Gen. Pavlov was fresh in Timoshenko’s mind.

Without giving them pause, on July 17 the Soviet Marshal ordered Lt. Gen. Konev and his Nineteenth Army to retake Smolensk. At the same time, orders were transmitted to the two armies in the Smolensk pocket to continue their attacks. While the Twentieth Army fought northwest of the city, Lukin’s Sixteenth Army attacked east toward the Nineteenth Army. As the fighting raged across Smolensk, the majority of the ancient city was turned to ruins. On July 19, Lukin’s men managed to capture a toehold in the northwest part of the city. In bitter house-to-house fighting amid the rubble of destroyed buildings, a precursor of things to come at Stalingrad, the Germans were completely pushed out of the northern part of Smolensk by the end of July 25.

In addition to Konev’s army, Timoshenko and the Soviet high command organized five task forces to take control of units that retreated to the line of the Dniepr and Vop Rivers, as well as some reserve units arriving at the front. After a short preparation, four of these combat groups, each numbering several infantry and tank divisions, were committed to the fight directly east of Smolensk, while another one, under the command of Lt. Gen. V.Y. Kachalov, formed around his Twenty-Eighth Army and operated farther south, west of Roslavl. A separate task force of three cavalry divisions was formed under Lt. Gen. Oka I. Ogorodnikov, a hero of the Russian Civil War, in order to conduct a deep raid into German rear areas.

The experiences of Maj. Gen. Konstantin K. Rokossovsky characterized the desperation with which the Soviets attempted to restore the situation at Smolensk. Arriving in Moscow on July 17 fresh from fighting in the Ukraine, Rokossovsky was placed in charge of one of the task forces, a group of two or three tank divisions and one rifle division. He was to proceed with all haste to take charge of the allocated formations in addition to being given permission to round up and take control of all units he encountered on the road from Moscow to Yartsevo.

However, he left the capital with only a handful of people: “The General Staff gave me two trucks mounting quad air defense machine guns with crews, a radio truck and a small group of officers,” he remembered. Several days later, his combat group absorbed the survivors of the VII Mechanized Corps, with the command element of the destroyed corps becoming Rokossovsky’s headquarters staff.

The newly created combat groups jumped off on July 23, and they immediately ran into determined German opposition with the furthest progress being roughly 12 miles. The intensity of the fighting is illustrated by the experience of the 101st Tank Division in Task Force Rokossovsky, which lost 140 of its roughly 170 tanks during the four days of fighting on July 18-21. Gorodovikov’s cavalry fought its way to the area of Bobruisk by July 24 at tremendous cost.

Characteristically, the Germans counterattacked. On July 29, the German panzers from two groups linked up at the Solovyevo crossing. They destroyed the pontoon bridge and captured the west side of the river. The Soviets doggedly fought on, however, and retained control of the eastern end of the river crossing, preventing the Germans from gaining a foothold on the east bank.

A Hasty Rout

Farther to the south, Kachalov’s task force, built around the bulk of his Twenty-Eighth Army, was almost completely surrounded on July 26 by several German formations, including the 2nd SS Division Das Reich and the Infantry Regiment Grossdeutschland. In a desperate attempt to fight clear of the encirclement, Lt. Gen. Kachalov was killed. Following on the heels of the retreating Russians, the Germans captured Roslavl on August 3.

The fight in the small area between Smolensk and Yartsevo turned into a slugfest, with both sides suffering horrendous casualties in the process. On July 30, after paying a high toll in men and equipment, Rokossovsky’s task force broke through to the two beleaguered armies at Smolensk. By this time, divisions of Sixteenth and Twentieth Armies were down to less than 2,000 men each. In addition to the Solovyevo crossing, Rokossovsky’s troops established another crossing farther north, near Golovino village, and the units from the 16th and 20th Armies began pouring through.

Instead of an organized Soviet withdrawal, the scene turned into a chaotic rout, with people desperate to escape literally storming the bridges. The first to escape were the rear support units, often abandoning valuable equipment and vehicles. Over the next several days, however, relative order was restored and the bulk of the survivors from the Sixteenth and Twentieth Armies crossed to the east bank of the Dniepr, abandoning the smoking ruins of Smolensk.

The retreat was accomplished under continuous German shelling and bombing. When the pontoon bridge at Golovino was destroyed, heavy equipment was routed to the Solovyevo crossing, while infantry and some horse-drawn artillery continued fording the Dniepr River, which was fortunately only two to three feet deep in this area.

Despite the majority of their men fighting bravely, the Soviet commanders had to constantly contend with breaks in morale. Rokossovsky later wrote, “To my great sorrow, about some things I do not have the right to remain silent; there were many instances of cowardice by the soldiers, panicking, desertion and self-mutilation to avoid having to fight. At first, the so-called ‘left-handers’ appeared, those who would shoot through the palm of their left hand or shoot off the thumb, or several fingers. When this came to light, the ‘right-handers’ appeared, doing similar things, but on the right hand. Sometimes mutilation was mutual: two men would shoot each other’s hands. A law was soon passed, allowing the use of the highest measure of punishment (the firing squad) for desertion, avoidance of battle, self-mutilation and insubordination in combat situations.”

The Germans Capture Yartsevo and Yelnya

As the fighting at Smolensk raged, the Soviets were making the best use of the time bought at such a high price. Two more defensive lines were established east of Smolensk on the road to Moscow, manned by four newly created armies, the Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Ninth, Thirtieth, and Thirty-First, plus the Twenty-Eighth and Thirty-Second Armies united into the Reserve Front under General Georgy Zhukov.

More than 300,000 civilians were put to work digging extensive earthworks, which consisted of tank traps, trenches, ditches, and other obstacles. Among those sent to work on fortifications was 18-year-old Moscow student Yevgeniy Bessonov. He recalled hard work under difficult conditions, often being strafed and bombed by German aircraft: “We worked 12 hours a day and, unaccustomed to physical labor, would become very exhausted. We would fall asleep as soon as we touched our ‘bed’ made from hay or straw, prepared mainly in barns. We dug antitank ditches, trenches along river banks, foxholes, and set up wire obstacles. In some instances we would repair railroad tracks after bombing and clear them of destroyed boxcars. But our main occupation was digging antitank ditches.”

Despite the Soviet propaganda claims about the widespread and enthusiastic support of the civilian population toward the war effort, Bessonov and his friends often experienced a lukewarm response from the locals. He remembered, “Food was poor and insufficient, and the village population was not distinguished by kindness. Our foreman, who arrived with us from Moscow, had to conduct talks with residents … about helping us at least with potatoes. Sometimes it helped.” One woman told Bessonov, justifying her refusal, “What am I going to feed the Germans when they get here soon?”

As more units arrived at the front, Zhukov began committing reserve armies into the fight east of Smolensk. Heavy fighting flared up at Yelnya, which was captured by the Germans on July 19. A salient penetrating eastward into the Soviet lines presented a convenient jump-off position for further German offensive efforts to the north, northeast, or southeast. The Soviet Twenty-Fourth Army contained the salient and with constant attacks did not allow it to expand, although the German position could not be eliminated by the Twenty-Fourth Army alone.

By this time, German infantry formations were beginning to catch up to their mechanized units, taking over the duties of containing Soviet counterattacks and reducing the Smolensk pocket. This freed panzer and motorized divisions to conduct more effective maneuvers. As a result, the 7th Panzer Division captured Yartsevo on July 22.

Clearing Yelnya

On August 29, following up on the successes of the Twenty-Fourth Army, Timoshenko ordered the newly arrived cavalry group of Colonel Lev M. Dovator into the gap. This two-division task force was to conduct a raid into the rear areas of German forces around Yartsevo. Leaving behind all of his artillery and support elements, Dovator launched his raid with the two cavalry divisions numbering 3,000 riders and 24 machine guns. After raising hell behind German lines for 10 days and covering almost 200 miles in extremely difficult roadless terrain, Dovator’s group fought its way clear and rejoined the main body of the Western Front.

Commander of the Twenty-Fourth Army, Maj. Gen. K.I. Rakutin, was allowed to call off his attack at the end of the third week of August and was given reinforcements to prepare for a more substantial attack. Rakutin’s plan called for a two-pincer offensive to link up west of Yelnya. Even though he gathered 60,000 men in seven divisions for the offensive, Rakutin’s force included only 35 tanks. Having less than a week to prepare and lacking sufficient armor, General Rakutin was short of the means to rapidly exploit any breakthroughs. In addition, the Twenty-Fourth Army lacked communications assets, air support was minimal, and many replacement soldiers had not finished even basic training. Only the artillery was plentiful and well supplied.

Rakutin’s attack began at 7 am on August 30, preceded by a massive artillery barrage. The central sector had only a supporting role, while the north and south wings executed the main offensive. Despite massive artillery fire and the heroic efforts of the infantry, the Soviet forces initially did not make any headway north of Yelnya and achieved only some local successes on the southern face of the salient. Rakutin relentlessly drove his men forward, however, and on September 5 the Twenty-Fourth Army fought its way into Yelnya. During two days of street fighting, the town was cleared. The entire Yelnya salient was cleared of Germans by September 9.

The German Offensive Slackens, the Soviets Regroup

The fighting around Yelnya marked an important date in the history of the Red Army. Since the beginning of the war, Stalin had wisely chosen to portray the fight against Hitler not as a struggle of two political systems, but as a battle for the survival of the Russian people. He revived the images of famous Russian commanders from centuries past, such as Suvorov, Kutuzov, Nakhimov, and others. Yelnya saw the rebirth of Russian Guard formations, elite units disbanded after the communist takeover in 1917. Two divisions of the Twenty-Fourth Army were the first to be renumbered into Guards divisions, the 100th and 127th into, respectively, the 1st and 2nd. By the end of September, two more divisions of the Twenty-Fourth Army were retitled into Guards.

The Soviet forces received help from an unexpected quarter when Hitler became concerned with the overall progress of the campaign. The success of Army Group Center was not matched by Army Groups North and South, which were beginning to fall behind schedule in the face of determined Soviet resistance. Especially bothersome for the Germans was the Soviet Fifth Army under Maj. Gen. Mikhail I. Potapov of the Southwestern Front. This army established itself at the easternmost edges of the extensive wooded and swampy area known as the Pripyat Marshes. Its location and active operations threatened both the right flank of Army Group Center and the left flank of Army Group South.

To stabilize the situation on the far-flung wings of the invasion, Hitler effectively ordered Army Group Center to go on the defensive on July 31, while turning Hoth’s panzer group north and Guderian’s south. But first the German high command called for a two-week halt in order to refit and reinforce its frontline formations, particularly panzer and motorized divisions. Without their panzer support, the infantry of Army Group Center conducted mainly local operations of tactical scope. Still, with very minor panzer participation, the German Ninth Field Army successfully trapped and largely destroyed the Soviet Twenty-First Army in the area of Gomel and the Twenty-Eighth Army in the area of Roslavl in early August.

This diversion of German resources was instrumental in allowing Zhukov and Rokossovsky to liquidate the Yelnya salient and bought the Soviets time to stage resources and prepare defenses for the struggle for Moscow. However, the significance of the Battle of Smolensk lies in the fact that it forced the Germans to modify Operation Barbarossa, signaling the end of the rapid German advance.

600,000 Casualties

The price the Soviet people paid for this respite was prohibitively high. While German losses were approximately 80,000 men, the Red Army suffered over 600,000 casualties, including almost 400,000 men taken prisoner. The fighting strength of five Soviet armies was destroyed, and they had to be reformed practically from scratch. A month after the Battle of Smolensk, seriously wounded Maj. Gen. Mikhail Lukin was taken prisoner during the disastrous campaign at Vyazma. With his right arm partially paralyzed and his right leg amputated at the knee, the tenacious general survived the war in Nazi captivity. He returned to the Soviet Union after the war and was briefly reinstated in the army before medically retiring in 1947.

Three bloody years later, Zhukov, Konev, and Rokossovsky came through this area again, this time pushing the German Army westward. In a reversal of fortune, they were instrumental in the destruction of their old nemesis, German Army Group Center.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments