By Herb Kugel

One of the most unusual baseball games ever played was a three- way game in New York City between the New York Yankees, the New York Giants, and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Each team went to bat six times in the same nine-inning game against rotating opponents. The final score was Dodgers 5, Yankees 1, and Giants 0, and the U.S. government was $56,500,000 richer in war bond sales.

Financing a World War

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the median income in the United States was about $2,000 a year. Those who were reasonably well off might be earning 85.3 cents an hour, the average hourly rate in 25 leading industries. Those who worked in a defense plant, one of many that kicked into high gear when Germany conquered France in 1940, could be making about $40.00 per week. Those who were far less fortunate could be one of the 7.5 million wage earners not covered by the legal minimum wage of 40 cents per hour, that is, $16 for a 40-hour week. In that case, these workers tried to get by on 15 cents an hour or even less.

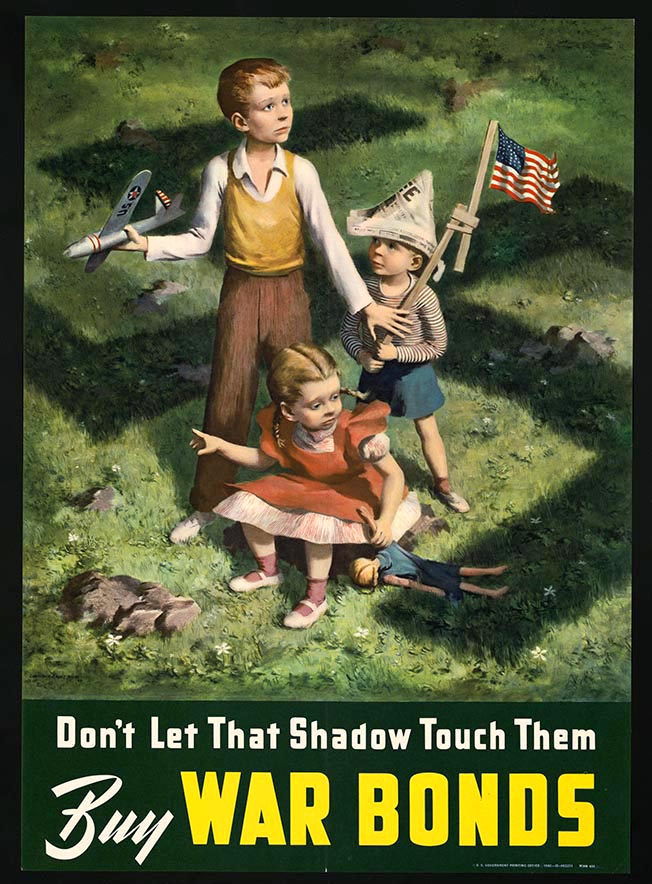

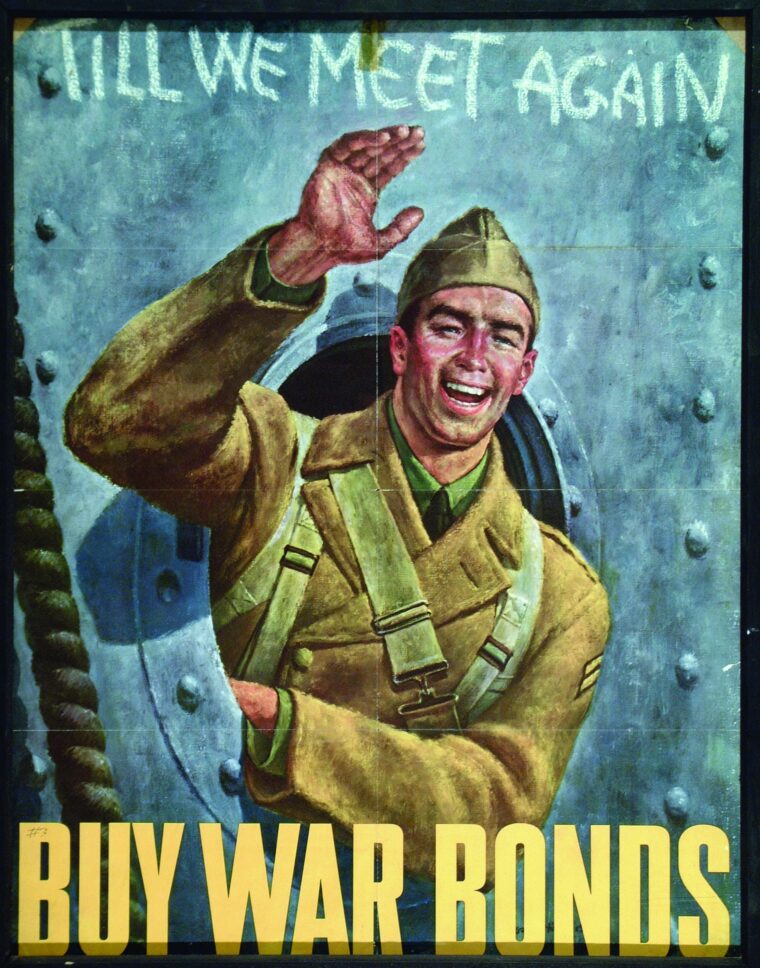

In any event, the total population of the United States, about 134 million, would be asked to help pay for the war effort during World War II by buying war bonds. Those who could not afford bonds were asked to buy stamps. These stamps, which sold from a dime up, could be saved toward the purchase of a bond. Everybody from President Franklin D. Roosevelt down through artists and movie stars to young women at makeshift stands pleaded with Americans to “buy war bonds.”

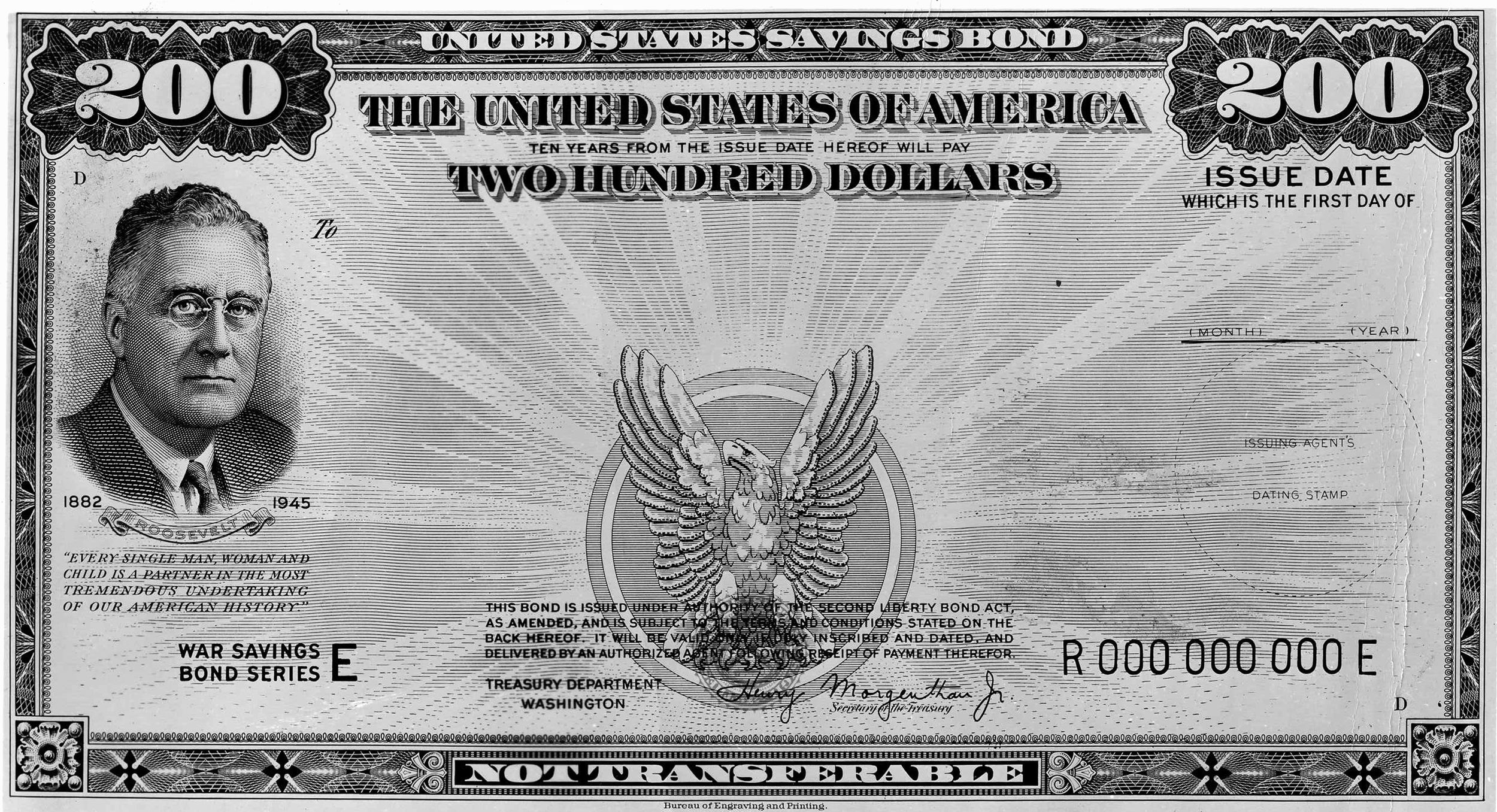

The war bonds the government wanted Americans to buy were the Series E bonds. On May 1, 1941, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau sold the first Series E bond to President Roosevelt. The bonds were accrual or zero-coupon bonds that sold at 75 percent of their face value in denominations of $10, $25, $50, $75, $100, $200, $500, $1,000, $10,000, and $100,000.

Selling the Bonds: An Advertising Feat

The War Finance Committee was given the job of supervising the sale of the bonds. The committee’s first task was to determine who would pay for the advertising campaign. Would the government pay or seek space and time contributions from newspapers and magazines or the radio networks? It was estimated that the cost of a nationwide advertising campaign could reach about $4 million a year, so the committee decided to solicit help from the media for the advertising.

The advertising campaign turned into a mammoth task. At first it focused on radio and newspapers since these appealed to a broad audience and could keep up with rapid changes in the news. However, the advertising was soon expanded to include magazines aimed at specific audiences and, since these diverse publications came out weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly, the campaign mushroomed. The magazine campaign with its varying needs proved to be far more complex than the radio-newspaper campaign.

The bond campaign was unique. Both the government and private companies created advertisements. Those who contributed advertising space felt they were doing more for the war effort since the money they would have been paid by the government could be channeled into military spending. The organizations that made up their own war bond advertising felt they could use this to show their patriotism to the public.

The campaign succeeded. Over a quarter billion dollars worth of advertising was donated during the first three years of the Defense Savings Program. To make the advertising appeal to the public, the government enlisted the help of New York’s best advertising agencies, dozens of entertainers, and even familiar comic strip characters. Bond rallies were held throughout the country, often led by entertainment personalities, usually Hollywood film stars. The advertising was effective. After one month of massive publicity, a poll revealed that over 90 percent of those questioned were aware of the War Bond Payroll Savings Plan (payroll deductions). The advertising for the bonds was often simple. Those who purchased a bond for $18.75 would get back $25.00 in 10 years. The New York Stock Exchange ran advertisements encouraging purchasers not to cash in their bonds.

The “Bond Blitz”

In September 1942, some eight months after film star Carole Lombard was killed in a plane crash while returning from a bond rally in January 1942, a rally in which she had raised some $2.5 million, Hollywood went over the top with a Stars Over America “bond blitz.” A total of 337 stars took part. They often worked 18 hours a day and were mobbed by the crowds of admiring fans that constantly engulfed them. Film stars Greer Garson, Bette Davis, and Rita Hayworth suffered varying degrees of physical and nervous exhaustion. Free movie days were often held, with the admission being a bond.

The Hollywood quota during the drive was $775 million, but more than $838 million in bonds were sold. Throughout the war, Hollywood stars made seven tours across 300 cities and towns. Glamour girl Dorothy Lamour, famous for her sarong, was credited with personally selling over $350 million in bonds. Another glamorous star, Hedy Lamarr, gave kisses to buyers of $25,000 bonds. One man became extremely excited and fainted before he could collect. Hollywood was not alone. Professional football and major league baseball did their share. Special games were held in which a war bond was the price of admission.

“Four Freedoms”

On January 6, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke of a world based on four freedoms in his message to Congress. “We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms,” he said. “The first is freedom of speech and expression everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear anywhere in the world.”

Roosevelt’s speech so inspired the artist-illustrator Norman Rockwell that he created a series of paintings based on his idea of the “Four Freedoms” theme. In his four paintings, he translated the abstract concepts of freedom into four scenes of everyday American life. Although the government initially rejected Rockwell’s offer to create the paintings, the images were publicly circulated when The Saturday Evening Post, one of the nation’s most popular magazines, reproduced them. The public loved them. After winning tremendous public approval, the paintings became a centerpiece in advertising the massive U.S. war bond drives. The Saturday Evening Post’s publishers produced copyrighted war bond posters using these paintings.

“Any Bonds Today?”

While Norman Rockwell was the war bond drives’ most notable artist, Irving Berlin was their most celebrated composer. In 1941, as his contribution to the national defense effort, Berlin, composer of “God Bless America” in 1939, wrote “Any Bonds Today?” This song became the theme song of the Department of the Treasury’s National Defense Savings Program. Many copies of the sheet music were distributed to help the government make the public aware of the savings bonds and savings stamp programs. In publishing this song, Berlin copyrighted it in the name of “Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury, Washington, D.C.” Although it was sung by many others, the famous Andrews Sisters were the primary performers known for this historic song. “The tall man with the high hat and the whiskers on his chin will soon be knocking at your door and you ought to be in. The tall man with the high hat will be coming down your way. Get your savings out when you hear him shout, ‘Any bonds today?’”

Of course, the “tall man” is Uncle Sam.

The Eight Loan Drives

The government organized a series of eight loan drives. The First War Loan began on November 30, 1942, and continued to December 23, 1942. The last drive, the Eighth or Victory Loan drive, took place October 29, 1945, through December 8, 1945. The war was over, but the last drive, like all the other drives, was a success. The quota for the Victory Loan was $11 billion. Over $21 billion was raised, an achievement of over 191 percent of the goal and the highest rate of success in any of the war loan drives.

In total, the eight war bond drives raised more than $156.4 billion, while over $180 million was donated by the private sector for advertising. A look at the Second and Third War Loan drives shows the magnitude of the task. The Second War Loan drive was completed on May 1, 1943, with over $18 billion being invested, $5.5 billion more than its goal. The Third War Loan drive, with its “Back the Attack” slogan, had a $15 billion goal. This meant that over 40 million Americans, about 30 percent of the population, would have to buy a $100 bond. President Roosevelt spoke on the radio on the evening of September 8, 1943, to start the drive, but the most successful single event by far was a 16-hour marathon radio broadcast on CBS featuring singer Kate Smith, who was already famous for her moving rendition of “God Bless America.” During her marathon, nearly $40 million in war bonds were sold. Approximately $23.4 million in advertising was donated, and the drive made sales of almost $19 billion.

Winning the War with the “Little Man’s Bond”

When President Roosevelt launched the voluntary sales program in 1941, his advisers feared there would be a resurgence of the unfair pressures that had been put upon those who did not participate in the voluntary World War I Liberty Bond program. Many who did not buy bonds at that time had their property damaged or painted yellow by people wishing to humiliate them. However, Morgenthau insisted that the World War II bond program operate on a voluntary basis to “make the country war-minded and give people an opportunity to do something.”

Every type of ballyhoo and hype was used to sell bonds, and the tireless and repeated hammering aimed at saturating every media of communication—radio, newspapers, magazines, and movies—continually carried the message with pleas and exhortations to “Buy War Bonds.” Even matchbox covers and milk bottle caps were drafted into service to carry the message. Because of the low prices at the bottom of its range, the Series E Bond was considered the “little man’s bond,” and without the little man America could not have paid for the war. Eight of every 13 Americans purchased bonds totaling over $185.7 billion.

The Series E bond was withdrawn on June 30, 1980. The Series EE Bond replaced it, and the war bond became history. Although it is now a part of American and world history, it is easy to imagine sitting in a darkened movie theater at the height of the war, perhaps a theater that was open 24 hours a day because the defense plants around it were operating continual shifts and people getting off work needed to unwind. The film is just ending; two lines suddenly fill the screen: THE END. Buy War Bonds and Stamps at This Theater.

Herb Kugel has done extensive research on the successful War Bond drives during World War II. He resides in Granville Ferry, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Hi Herb,

Your articles have helped me for some time. I appreciate you. I have some items from my dad’s service in WWll and have no idea about the values or even what some of them are. Could you suggest where I might learn about them?

I also served with the USO during Nam. I have several bracelets of missing Vets. How may I learn of they were ever found? What can I do with the old bracelets we bought and wore?

Thank you much