By Michael D. Hull

Located 58 miles south of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea, the rocky, 122-square-mile island of Malta was the hinge upon which all Allied operations in the Middle East turned during the first half of World War II.

Torpedo bombers and submarines operating from the British crown colony and naval base maintained the only effective striking force against Axis convoys to North Africa. In the summer of 1942, only 40 percent of German supply ships were reaching Tunisia to nourish Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps and his Italian allies.

Malta: Linchpin of the Mediterranean

Malta was a strategic linchpin and, therefore, a prime target of the enemy. For the bitter years of 1940-1942, German and Italian bombers bludgeoned the island in a vain effort to pound it into submission, but the defenders—British troops and the staunch Maltese islanders— fought the longest epic defense action of the war. The tiny garrison never exceeded 25,000 fighting men, a few squadrons of Royal Air Force Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane fighters, and two flotillas of Royal Navy submarines.

Almost daily, the enemy bombers and fighters bombed and strafed Malta and its installations, while antiaircraft batteries fired back and the islanders took shelter in limestone tunnels and caves. It was a desperate time. Almost every building on the island was destroyed or damaged, and the soldiers and airmen rarely left their trenches and air raid shelters, ready at any hour for the dreaded arrival of enemy parachute and glider-borne invaders.

An Island Pushed to its Limits

Malta held on defiantly as the free world watched, but the situation became increasingly critical. Failing to overwhelm its defenders, the enemy clamped a tight blockade around Malta. As the island’s resources ran low, the question of relief challenged Allied planners. In the first half of 1942, only one merchant ship in seven was able to breach the blockade. There was a slender lifeline. British minelaying submarines based in Alexandria, Egypt—HMS Cachalot, HMS Porpoise, HMS Rorqual, HMS Osiris, HMS Urge, and others—were able to steal through with modest cargoes of medical stores, kerosene, armor-piercing shells, powdered milk, gasoline, and mailbags. But it was not enough.

Hardship and shortages beset Malta’s defenders. The civilian population was subjected to tight rationing, subsisting on only 16 ounces of food a day. Fighter planes were forbidden to taxi to and from runways in order to conserve fuel. They were towed by trucks. Antiaircraft batteries were limited to 20 shells or four ammunition belts a day, according to caliber.

Malta had to be kept in the war somehow. The Germans and Italians were determined to knock it out. Between March and June 1942, no Allied ships reached the island. Each convoy making a relief effort was massacred by enemy planes and submarines. That July, with the outlook grimmer than ever, General John V. Gort, the governor of Malta, sent a signal to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: “Estimate food and petrol stocks will be exhausted by August 21 in spite of severe rationing. Hesitate to request further naval sacrifices, but cannot guarantee Malta’s safety after this date without further supplies.” The message from Gort, a much-decorated hero of World War I and the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation, was an understatement of the island’s plight.

Forming the Pedestal Convoy

Hastily, the British Admiralty planned a desperate attempt to beat Lord Gort’s deadline and save Malta—a large relief convoy code-named Operation Pedestal. It would be the most powerful convoy yet attempted, with a heavy fleet escort of battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers shepherding 13 merchant ships and a tanker. On this complex operation—the most dangerous Allied convoy yet undertaken —depended the survival of Malta and, indirectly, the fate of millions.

The heavy escort was to be provided by two venerable sister battleships, HMS Nelson and HMS Rodney, each displacing 34,000 tons and armed with nine 16-inch guns and a dozen six-inchers. Vice Admiral Sir Neville Syfret flew his flag in Nelson, as flag officer commanding what was called Force Z. With him would go a squadron of three aircraft carriers—the new HMS Indomitable, the 1939-built HMS Victorious, and the aging HMS Eagle. Commanded by Rear Admiral A.L. St. George Lyster, carrying his flag in Indomitable, the three flattops mounted 46 Hurricanes, 10 Grumman Martlets (Wildcats), and 16 Fairey Fulmars of the Fleet Air Arm to provide fighter cover.

With this main escort would be three fast antiaircraft cruisers—HMS Charybdis, HMS Phoebe, and HMS Sirius—and 14 destroyers. Providing close escort to the merchantmen were the heavy cruisers HMS Nigeria, HMS Kenya, and HMS Manchester, and the antiaircraft cruiser HMS Cairo, comprising Force X and led by Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough. The mission of this force, supported by 11 destroyers, was to cover the convoy through to Malta after Force Z had turned back to the Skerki Narrows, between Tunisia and southwestern Sicily.

In a separate operation from Pedestal, the carrier HMS Furious, with a destroyer escort, was to fly off 38 Spitfire fighters as reinforcements for Malta. Backing up the fleet were two oilers with a corvette escort, a deep-sea rescue tug, and a salvage vessel. All in all, it was the largest naval operation to be set in motion in the Mediterranean.

The fast merchant ships carrying 42,000 tons of food, flour, ammunition, and other supplies to beleaguered Malta were the Port Chalmers, in which the convoy commodore Royal Navy Commander A.G. Venables flew his pennant; Santa Elisa and Almeria Lykes, American-owned and -manned general cargo ships; Wairangi, Waimarama, and Empire Hope of the Shaw Savill Line; Brisbane Star and Melbourne Star of the Blue Star Line; Dorset of Federal Steam Navigation Co.; Rochester Castle of the Union Castle Line; Deucalion of the Blue Funnel Line; Glenorchy of the Glen Line; and Clan Ferguson of the Clan Line. The 14th cargo vessel, and arguably the most important because she was carrying desperately needed aviation fuel, was the new, 14,000-ton tanker Ohio. Owned by Texaco Oil Co., she had been loaned to the British for a special convoy. Ohio was manned by volunteer British seamen and commanded by Captain Dudley W. Mason of Eagle Oil & Shipping Co. of London. The tanker’s ordeal in the Mediterranean would be hailed as one of the maritime epics of World War II.

Although no attempt was to be made to pass a second convoy through from the eastern end of the Mediterranean as had been done before, a cover plan was devised whereby Admiral Sir Henry Harwood would mount a dummy operation from Alexandria in company with Admiral Sir Philip Vian from Haifa, Palestine. The idea was to confuse waiting German and Italian naval and air units, whose commanders knew that the British would make another attempt to relieve besieged Malta. A total of five cruisers, 15 destroyers, and five merchantmen would sail as if bound for Malta, and then, on the second night out, disperse and turn back. It was hoped that this would tie down some of the enemy forces.

Meanwhile, Air Vice Marshal Keith Park on Malta was to hold in readiness a torpedo bomber strike force in case the Italian Fleet might be tempted to leave its major base at Taranto. Park, a distinguished fighter group leader in the 1940 Battle of Britain, would keep the rest of his air strength, 130 fighters, for support of the Pedestal convoy. Six Royal Navy submarines from Malta were to patrol west of the island in case Italian warships tried to interfere in the area of Pantelleria, while two would prowl to the north of Sicily.

Even as the Pedestal ships were loaded and crews mustered in Scotland’s River Clyde, the enemy waited in the Mediterranean. German and Italian bombers, dive-bombers, and torpedo planes were lined up on the airfields of Sicily and Sardinia along with fighters and reconnaissance aircraft. About 70 planes were on alert as a reception committee for the British convoy. Eighteen Italian submarines and three German U-boats were on patrol off Malta and between Algiers and the Balearic Islands; German E-boats and Italian motor torpedo boats lay in wait off Cape Bon, Tunisia, where a new minefield had been sown, and three heavy and three light cruisers along with 10 destroyers were ready to intercept the Pedestal convoy south of Sicily.

“Secrecy is Essential”

As the convoy ships assembled in the Clyde, Captain Mason, the lithe, 40-year-old skipper of the tanker Ohio, briefed his crew in the petty officers’ mess. “We sail this afternoon,” he said quietly. “Our destination is Malta; you all know what that means…. Ohio is the only tanker. We shall have to fight with 13,000 tons of high-octane fuel aboard. Now is the time for anyone who wants to back out to say so. I must warn you that if you choose to go ashore, you will be kept in custody of the naval provost marshal until the operation is over. Secrecy is essential.”

He paused, and there was no movement from his tense crew members. Holding a letter from the Admiralty, Mason continued, “Before you start on this operation, the First Sea Lord and I are anxious that you should know how grateful the Board of Admiralty are to you for undertaking this difficult task. Malta has for some time been in great danger. It is imperative that she be kept supplied. These are her critical months, and we cannot fail her. She has stood up to the most violent attacks from the air that have ever been made. Her courage is worthy of you. We wish you God speed and good luck.”

Mason, shy but firm, and a veteran of several naval actions, left the mess to prepare for getting underway. The convoy formed up outside the Clyde on the afternoon of Sunday, August 2, 1942, and set course southward for the British bastion of Gibraltar at the western end of the Mediterranean. The ships steamed in three parallel columns, and the crews were told their destination on the first morning at sea. Additional Oerlikon and heavier antiaircraft guns had been mounted on the freighters’ decks, and the Royal Navy and Maritime Regiment crews underwent constant exercises.

Ohio was fourth in line in the starboard column. Mason paced the bridge, fearful of what lay ahead. Based on the fates of previous Malta convoys, he knew that as many as a dozen of the 14 ships would probably not reach the island. A camp bed had been set up on the bridge for Mason, but it would be seldom used in the grim days ahead.

The Pedestal ships forged southward into the Bay of Biscay, where U-boats and Focke-Wulf bombers prowled. It was feared that the convoy would have to run a deadly gauntlet, but there were only occasional skirmishes, which were swiftly dealt with by Royal Navy escorts. There was no serious threat to the convoy, yet.

The Convoy Enters the Mediterranean

At dawn on Sunday, August 9, the convoy wheeled from the Atlantic through the Gibraltar Strait and into the warm Mediterranean. Nine destroyers hugged the convoy on either beam and up ahead, while close astern three more destroyers shepherded the carriers Illustrious and Eagle. Well ahead on the horizon steamed four cruisers with attendant destroyers, while, far out on the port beam, five cruisers and six destroyers screened the carriers Indomitable and Victorious. It was an impressive display of naval might.

Tension mounted on the bridges and decks of all vessels as Admiral Harold Burrough flashed an ominous signal from his flagship, the cruiser HMS Nigeria: “All ships to action stations until further notice!”

During the convoy’s first day in the Mediterranean, the enemy kept out of sight. There were false alarms and brief bursts of gunfire from tense antiaircraft crews aboard the ships. The second day passed in the same way, with the gunners testing their weapons, eating hurried meals, and maintaining vigilance.

The First Axis Strike

Dawn on the third day, Tuesday, August 11, came calm, sunny, and deceptively serene. Then, Captain Mason of the Ohio and hundreds of other men throughout the convoy stiffened when they heard the faint rhythm of aircraft engines. As Mason trained his binoculars on tiny silver specks 20,000 feet above, the serenity was shattered rudely and swiftly. Bombs screamed down, and a merchant ship astern of the Ohio vanished behind a curtain of flame, cordite, and water splashes. A stick of bombs fell across the gap between Ohio’s bows and the stern of the ship ahead as the attack intensified.

The carriers swung into the wind to launch their fighters, and the combined guns of the convoy blasted a reply to the enemy. Two near misses to port drenched the tanker’s bridge, and Mason fought back an urge to take avoiding action. He was under strict orders to maintain course and speed unless his vessel was directly threatened.

Meanwhile, an Italian submarine made an unsuccessful attack on the carriers, and German and Italian reconnaissance planes located the convoy. The ordeal of the Pedestal convoy was underway. The 24 British destroyers and the cruiser HMS Cairo took on fuel from the three-tanker supply force, while, south of the Balearic Islands, the carrier HMS Furious flew off 37 Spitfires for Malta and was then met by the reserve destroyers Keppel, Malcolm, Venomous, Wolverine, and Wrestler for the return journey to Gibraltar.

A German U-boat, U-73, commanded by Lieutenant Helmut Rosenbaum, stalked the convoy and succeeded in diving undetected beneath the destroyer screen. Shortly after 1 pm on August 11, he loosed a salvo of four torpedoes at the carrier Eagle. All four struck, and a huge hole was blown in the port side of the gallant ship, which had dispatched 183 Spitfires to Malta during the past year. Her squadrons of fighters, ready for takeoff, cascaded overboard as Eagle toppled on her side. The aging flattop —launched in 1918 as a Chilean battleship and completed as a carrier in 1923—sank in eight minutes. Two hundred and sixty pilots and flight deck crewmen perished, and the rest of her 1,160-man complement was rescued by destroyers and the fleet tug Jaunty.

Flying at 100 feet above the water, Italian torpedo bombers swept in to attack the convoy. On the Ohio’s bridge, Captain Mason watched in horror as the leading ship in the port column disintegrated under the impact of two hits. Mason’s quartermaster struggled to keep the laden tanker steady as torpedoes straddled her, some no more than 10 feet away. The convoy’s gunners fired back tirelessly at the raiders, and the enemy’s first assault was beaten off, but not without losses. Meanwhile, the British fought back desperately. Ten RAF Bristol Beaufighters and 16 Hurricanes raided Italian air bases in Sardinia.

A Moonlit Battle

The convoy sailed on, waiting for the next attack to develop. It came in the late afternoon when 80 torpedo bombers, more than 200 Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers, and a covering force of 100 fighters came in from all directions. The ships’ gunners opened up again, and the carriers Victorious, Indomitable, and Illustrious flew off every available fighter to meet the new threat. Captain Mason watched the Stukas break formation and scream down in almost vertical dives. Bombs and torpedoes plastered the convoy, and the Ohio was the principal target. The tanker moved sluggishly as bombs fell ahead, astern, and on either side of her. Miraculously, the Ohio emerged unscathed from the inferno.

The enemy planes headed for home, and the Pedestal convoy was left in peace for half an hour. The welcome respite was all too brief, and the third attack of the day came without warning as 100 Stukas plummeted suddenly on the convoy. The ship ahead of the Ohio erupted in roaring flame, while a cloud of dive-bombers descended on an ammunition freighter opposite Ohio in the port column. She exploded with a huge flash that seared Captain Mason’s face 300 yards away. There were no survivors.

The evening of August 11 closed in. Against the glow of the setting sun, the sky was black with bursting shells interlaced with streaming tracers. The scorecard for the furious day was not encouraging. Eight enemy bombers, 12 torpedo bombers, and 26 Stukas had been shot down, but the convoy had lost a carrier, two destroyers, and three freighters. Six Fleet Air Arm fighters had failed to return.

At midnight, the raiders returned—36 German Junkers Ju-88 and Heinkel He-111 bombers. The ships’ antiaircraft crews sprang into action again, and the carriers launched their fighters without pretense at blackouts. A great moonlit air battle raged in the deep blue high above the convoy, and the raiders were driven off shortly before dawn. The scorecard showed some improvement for Pedestal. Another merchantman had been sunk, but four enemy bombers had been shot down and two U-boats claimed as destroyed. Aboard the Ohio, the chief engineer reported to Captain Mason, “Leak in port side of engine room, sir. Near miss blew in some rivets. We are shoring up now.”

The destroyer HMS Wolverine rammed and sank an Italian submarine attempting to attack the returning carrier HMS Furious, and a Short Sunderland flying boat bombed and damaged another Italian submarine.

Continuing Without the Ohio

The convoy battle resumed about an hour after dawn with the arrival of 19 Ju-88s from the north. The merchant ships dodged bombs and torpedoes while destroyers hunted U-boats and the carriers threw up a canopy of gunfire. Through it all, the Ohio butted slowly forward between near misses. Six planes were downed and the rest driven off. At midday, the convoy was again assaulted, this time by 98 Italian and German bombers and torpedo planes. The transport Deucalion was damaged and left behind with the destroyer HMS Bramham. Two Italian bombers hit the carrier HMS Victorious, but their armor-piercing bombs rebounded from her armored deck.

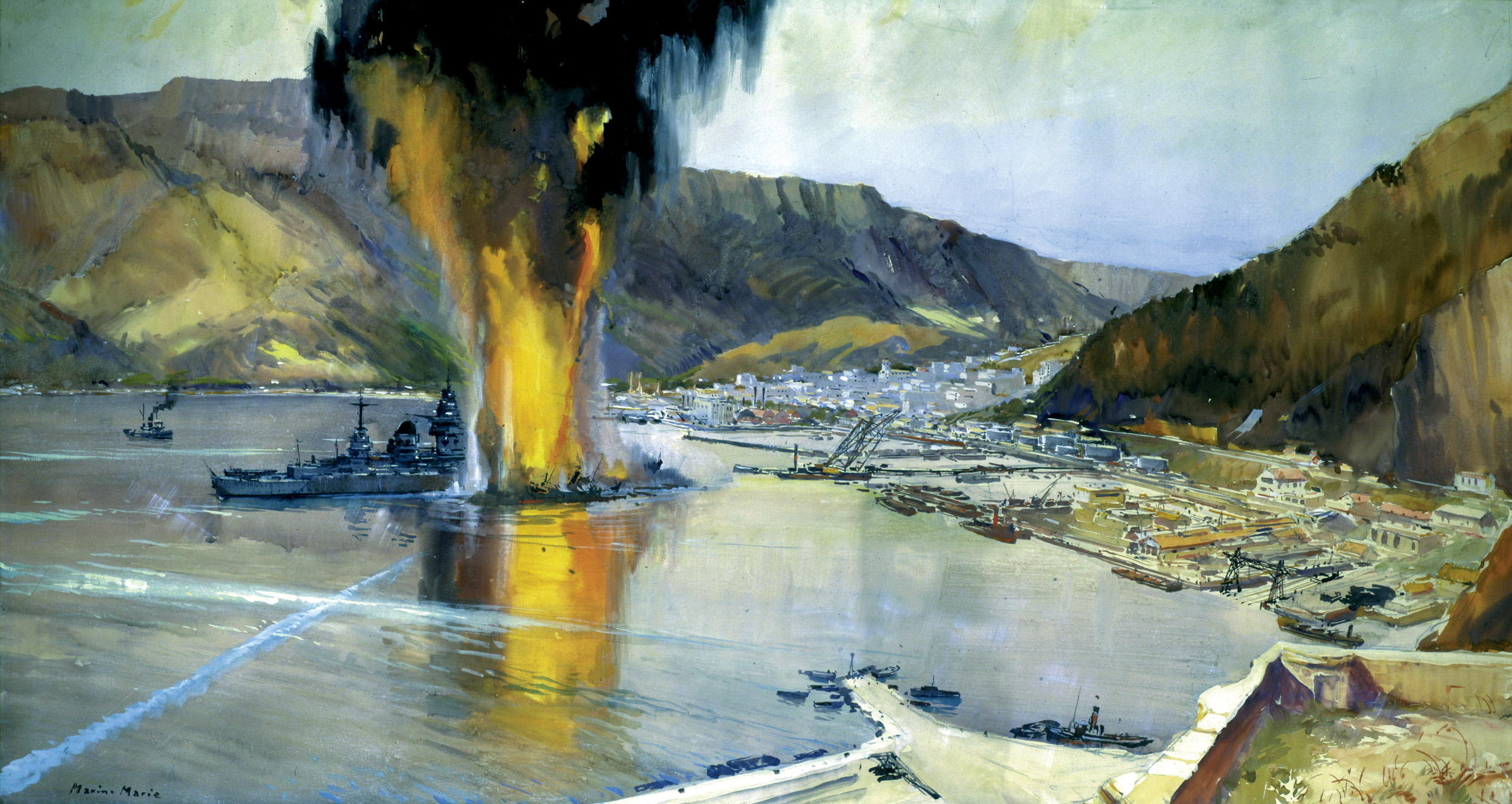

During the afternoon of August 12, enemy submarines were repeatedly repelled by the destroyers Tartar, Zetland, and Pathfinder. Later that afternoon, 29 Stukas scored three severe hits on the carrier HMS Indomitable, which was then unable to operate aircraft. Fourteen Italian torpedo bombers crippled the destroyer HMS Foresight, which later had to be sunk by HMS Tartar. After a pause at dusk, two Italian submarines sneaked in close to the convoy, scoring hits on the cruisers Cairo and Nigeria and the Ohio. Cairo had to be abandoned, and Nigeria turned back with three destroyers.

While her exhausted, sweating gunners were collapsed at their stations, two torpedoes struck the Ohio near the bow on the starboard side. She staggered under the shock as part of the main deck gave in, her steering gear broke down, and communications between the bridge and the engine room were severed. But the engines turned, and Captain Mason sighed with relief. Soon, however, even this was denied. The engine room became silent, and the wrecked generators darkened the tanker. As night fell, the enemy pursued the convoy while the Ohio, drifting helplessly further astern, was left alone. There was no time to waste on crippled ships.

At dawn on August 13, patrolling enemy planes sighted the tanker and attacked her continuously throughout the fifth morning. Shortly after noon, two destroyers raced back from the convoy. HMS Ashanti, Admiral Burrough’s flagship, ranged alongside the Ohio. Over a loudspeaker, he hailed Captain Mason, “What are your chances of rejoining the convoy?” Mason, having no loudspeaker, gave a laconic thumbs-down signal. “Sorry about this,” the admiral shouted. “We wanted you to get through most of all. Now I must get back to the convoy and report your position to the rescue ships. Good luck!” The destroyers departed at full speed, leaving Ohio alone to face whatever lay ahead.

The convoy, meanwhile, received another pasting from the air. Thirty Ju-88s bombed the transports Empire Hope and Glenorchy, and seven He-111s forced the Brisbane Star to halt. An Italian submarine torpedoed and damaged the cruiser HMS Kenya and the freighter Clan Ferguson, and another Italian submarine finished off the Empire Hope. Several hundred miles away in the eastern Mediterranean, the second half of the Pedestal attempt to relieve Malta failed. Admiral Vian’s convoy of eight merchantmen was forced to take violent evasive action to avoid the full might of the Italian Fleet. Five freighters were sunk by planes and a sixth torpedoed. The other two were so damaged that they were beached on the North African coast.

On August 13, in a desperate bid to distract enemy attention from Admiral Burrough’s battered convoy, the cruisers Arethusa and Cleopatra and the destroyers Javelin, Kelvin, Sikh, and Zulu bombarded enemy installations on the island of Rhodes. But the attacks on the convoy continued as Italian motor torpedo boats swept in 15 times in four hours. They severely damaged the cruiser Manchester, which had to be abandoned, and sank the crippled freighter Glenorchy and the Santa Elisa, Almeria Lykes, and Wairangi.

Bringing the Ohio Back to Life

Throughout the afternoon of August 13, the crew of the listing Ohio toiled to restore her power. Around 4 pm, she began to vibrate with a familiar throb, and her propellers turned. Ragged cheers broke out from the weary crewmen. The engines held, Captain Mason ordered full speed ahead, and the tanker pursued the convoy at 17 knots. That night, the cruiser Charybdis and destroyers Eskimo and Somali joined the convoy as reinforcements.

At daylight on August 14, the sixth morning of the operation, the Ohio caught up with the convoy and resumed her station in the starboard column. She was greeted by the sirens and hooters of her fellow merchantmen and escorts, but Captain Mason was stunned at the pitiful depletion of the convoy. An hour later, the enemy air attacks resumed. He-111s, Ju-88s, Ju-87s, and Italian SM-79 torpedo bombers sank the transport Waimarama and scored hits on the transports Dorset, Port Chalmers, and Rochester Castle.

The sole tanker in the tiny fleet was not spared. A crippled Stuka smashed into the Ohio and exploded on her foredeck, starting fires. Crewmen rushed to heave the burning plane over the side as a bomb hit the afterdeck, killing 10 gunners. Two more bombs straddled the tanker, lifting her out of the water. She dropped back on one side, threatening for a moment to capsize. By the time the Ohio and her blackened crew had recovered, the engines had gone silent again. Once more, she was wallowing astern of the convoy.

The tanker’s engineers went to work again, and, through some miracle of mechanical ingenuity, got the engines started after two hours’ effort. The Ohio moved forward at four knots an hour. At noon on August 14, the port boiler blew up and wrecked the main deck aft of the bridge. The Ohio stopped, and then the starboard boiler also exploded, killing a dozen engineers and six deck hands fighting the fires. The tanker was a blackened shambles by now.

Overwhelmed, Captain Mason grabbed a signal lamp and sent a message to the nearest ship for relaying to the destroyer HMS Ashanti: “Unable to proceed further. Can remain afloat for only a few hours. Can you help?”

Admiral Burrough responded by dispatching two destroyers to take the tanker in tow, and for the next six hours the three ships fought off air attacks while trying to pass towlines to each other. Dusk brought synchronized attacks by Italian motor torpedo boats and bombers. When six of the enemy boats raced toward the Ohio to finish her off, the destroyers broke off towing operations to intercept. One of them ran into a torpedo intended for the tanker, blew up, and sank in seconds. The other destroyer drove off the motor torpedo boats with her guns, picked up the survivors of her sister ship, and drew alongside the Ohio again.

Her captain shouted, “I’ll stay with you and radio for more help.” Half an hour later another destroyer arrived to circle the tanker as protection against the torpedo boats.

“They Need You to Survive”

The Ohio was in sorry shape as she limped along, low in the water. Half of the crew was dead and 10 seriously wounded. Other wounded crewmen helped to keep the few remaining batteries firing. Captain Mason, who had gone for several nights without sleep, was exhausted. If his crippled ship could make it into the Grand Harbor at Valletta, it would be a miracle, but he never gave up hope.

He was preoccupied when he suddenly heard the high-pitched whine of a falling bomb. He knew instinctively that it would hit the Ohio. A second later, it crashed through the superstructure behind the bridge, exploded in the engine room, and blew a 15-foot hole in the port side. Mercifully, it was above the water line. The attacks continued. Throughout the night of August 14, the tanker and her two attendant destroyers fought off one torpedo boat attack after another. The shattered tanker was lower in the water, but help was on the way.

After the surviving merchantmen—Melbourne Star, Port Chalmers, and Rochester Castle—had arrived safely at Malta, met by seven minesweepers, Admiral Burrough dispatched his Fleet Air Arm fighters to shield the lagging Ohio. The two destroyers on each side of the tanker passed wire hawsers to each other under her keel in order to keep her afloat.

The Ohio no longer floated; she was resting on a jury-rigged network of wires. The bizarre threesome plodded on toward Malta. When Burrough’s cruiser squadron steamed past on its way back to Gibraltar, the admiral signaled, “Only three ships got through with provisions and ammunition. They need you to survive. RAF are making final sorties with exhausted fuel today and tomorrow. All Malta awaits your arrival. God bless you. I am proud to have sailed with you.”

Arriving in Malta

The Ohio and her two shepherds were approaching Malta at last, but the enemy did not give up. German fighters swarmed overhead and clashed with the Fleet Air Arm umbrella, while bombers dived yet again. A near miss carried away the Ohio’s rudder and blew a hole in her stern. Water poured in, and she settled even lower, dragging down the destroyers under her weight.

The situation improved at 8 pm on August 14, when Malta was sighted. Tugs sailed out to assist the three ships, and Captain Mason gained the respite for which he had prayed. Confident that the Ohio was sinking rapidly, the enemy called off their attacks. That night, the tanker and destroyer crews, aided by the tugs, struggled to keep the Ohio afloat by passing more hawsers beneath her.

When dawn broke on August 15, the Ohio was only a mile outside Valletta harbor. It was the Maltese national holiday, the Feast of Santa Marija. On the island, thousands of civilians mingled with British soldiers, sailors, and airmen on the quaysides. On rooftops and both sides of the craggy harbor entrance, they silently watched the miracle of deliverance—the Ohio’s survival and their own. Fussed over by the tugs and accompanied by the destroyers Penn, Ledbury, and Bramham, the smoking, wallowing tanker took an hour to cover the last mile.

As her battered bows passed between the outer moles of the harbor, the silence ashore was broken by a faint cheer. Then the applause swelled, drowning the thunder of guns fired in salute. Union Jacks and handkerchiefs were waved, turning the quayside crowds into a mass of heaving color. A military band played “Tipperary,” the “Beer Barrel Polka,” and other wartime hymns of hope. Aboard the Ohio, Captain Mason paused from helping to keep the fires under control, gave a faint smile, and wept unashamedly. His grim prediction about the convoy’s fate had proved accurate.

While the stricken tanker was being nudged alongside the harbor’s oil wharves, signals to Mason poured in. Prime Minister Winston Churchill said, “Splendid work; well done,” and a message from the Admiralty in London read simply, “Well done, Ohio.” Lord Gort spoke for the islanders themselves: “We are all so happy to see you and your fine ship safely in harbor after such an anxious and hazardous passage. You have saved Malta.”

Recognizing the Heroism of Operation Pedestal

The Ohio, whose decks had been awash for a long time, was berthed alongside the sunken auxiliary tanker Plumleaf at the Parlatorio Wharf. As her cargo of 13,000 tons of aviation gasoline was unloaded that day, the Ohio began to settle on the bottom. It had been a close thing. On the evening of August 15, the commander of the RAF fighters in Malta reported to Lord Gort that he could now mount unlimited combat sorties for two months.

Meanwhile, a fourth crippled merchantman, the Brisbane Star, had reached the island. A total of 32,000 tons of food, ammunition, and other supplies was offloaded, enough to sustain the island bastion for about 10 more weeks. The matériel landed was not enough to release the islanders from their near-starvation rations (1,500 calories a day), but it was sufficient to keep Malta going. The Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy had saved Malta. It did not mean the end of the island’s siege, but the costly Operation Pedestal enabled strategic Malta to stay in the war. Malta’s fall would have nullified Allied plans for the invasion of North Africa in November 1942.

Admiral Syfret reported, “Tribute has been paid to the personnel of His Majesty’s ships; but both officers and men will desire to give first place to the conduct, courage, and determination of the masters, officers, and men of the merchant ships. The steadfast manner in which these ships pressed on their way to Malta through all the attacks, answering every maneuvering signal like a well-trained fleet unit, was a most inspiring sight.”

The First Sea Lord reported to Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, commander in chief of the British Mediterranean Fleet, who was then in Washington, “We paid a heavy price, but personally I think we got out of it lightly, considering the risks we had to run, and the tremendous concentration of everything … which we had to face.”

Among the decorations awarded to survivors of Operation Pedestal, Captain Mason was given the George Cross, Britain’s highest award for a noncombatant, in recognition of his heroism and seamanship. Twenty-three of his sailors and gunners were also decorated. On April 15, 1942, King George VI had awarded the George Cross to the “brave people” of Malta for their “heroism and devotion,” the only time in history that an island has been given a medal.

Malta never forgot Operation Pedestal and the Ohio. In 1946, crowds cheered and bands played as the rusty hulk of the tanker was towed out of the Grand Harbor for the last time. While a remembrance service was conducted for those who died in the convoy, she was sunk in the waters she had plied during one of the naval epics of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments