By J.D. Haines

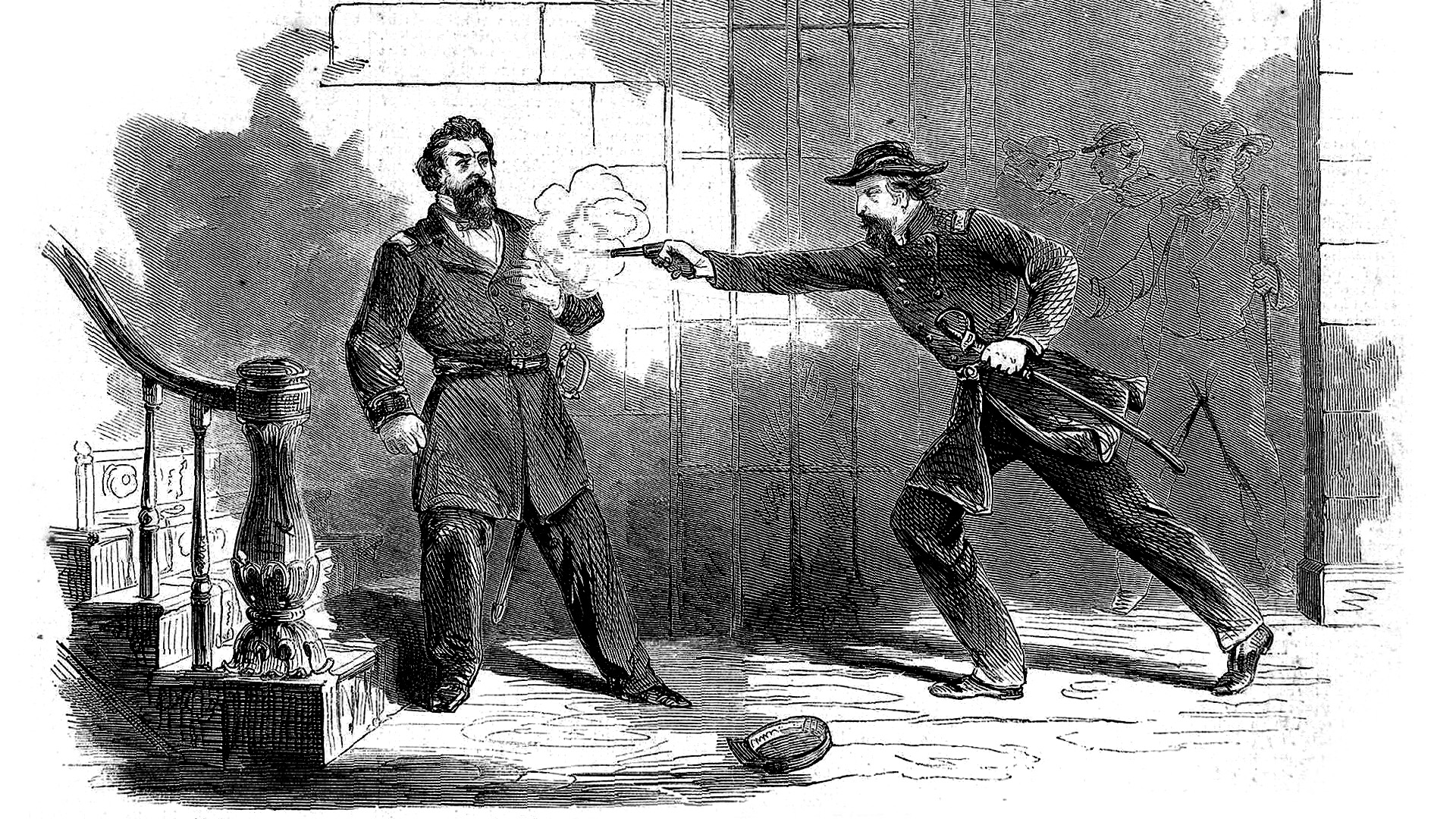

Following his greatest victory, at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was scouting ahead of the lines with members of his staff when tragedy struck. In the pitch blackness of the early-spring evening, Jackson and his men were mistaken for Union cavalry and fired upon by their own side. Jackson sustained a severe wound to his upper left arm, necessitating amputation. Upon hearing the news, victorious General Robert E. Lee remarked, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.” Lee’s words proved prophetic. Eight days after the amputation, Jackson was dead.

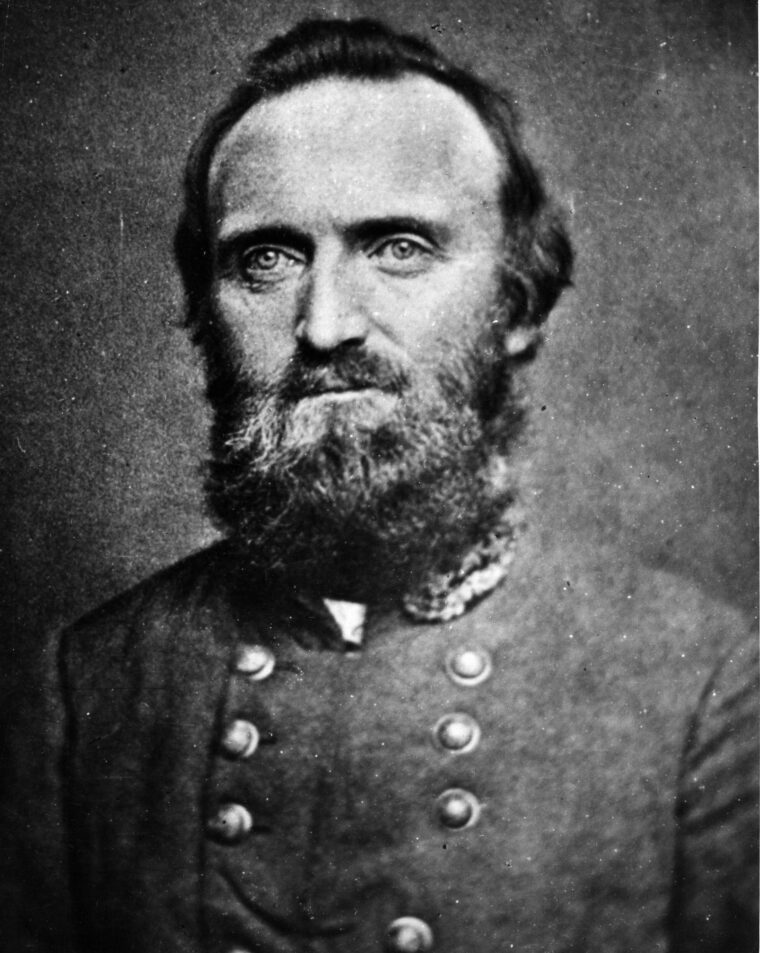

It was a loss the Confederacy could ill afford. Before Chancellorsville, Jackson had enjoyed the fortuitous combination of personal skill as a commander, the ineptitude of his opponents, and the good luck that often follows such a combination. He had begun the Civil War as an unknown professor at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, after having distinguished himself during the Mexican War 15 years earlier. Fresh out of the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he had graduated a hard-won 17th in a class of 59, Jackson had earned two brevets for gallantry as an artillery officer during the Mexican War. By the end of the war, he had become a brevet major at the age of 24. He resigned his commission in 1852 to take the position of professor of artillery tactics and natural philosophy at VMI.

Jackson Volunteers for War

Jackson was commissioned a colonel of volunteers in April 1861 and promoted to brigadier general two months later. He won fame at the Battle of First Manassas on July 21, 1861, where his staunch defense of Henry Hill earned him the memorable nickname “Stonewall.” He was promoted to major general in October and appointed commander of all Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley the following month.

In the subsequent Shenandoah Valley campaign, Jackson fought a masterful series of battles against a greatly superior Union force. In doing so, his men prevented the reinforcement of Maj. Gen. George McClellan during McClellan’s drive on Richmond, probably saving the Confederate capital. After being repulsed at Kernstown, Jackson outmaneuvered and defeated enemy forces at Front Royal, Cross Keys, and Port Republic between May 23 and June 9, 1862. His campaign, long regarded by military historians as a tactical masterpiece, proved him to be a fearless and aggressive commander, a brilliant tactician, and a master of rapid maneuver. He summarized his approach to generalship as “always mystify, mislead and surprise the enemy.” This strategy also applied to his own subordinates, who were rarely informed of Jackson’s plans beforehand. Jackson consulted only with Robert E. Lee.

Jackson rejoined Lee in driving McClellan from the peninsula during the Seven Days’ Battles between June 26 and July 2. Jackson next destroyed Maj. Gen. John Pope’s supply depot at Manassas Junction on August 27 and repulsed Pope’s counterattack at Groveton the next day. He contributed substantially to Lee’s crushing victory over Pope at Second Manassas on August 29-30. During the invasion of Maryland, Jackson won added distinction at the Battle of Antietam. Despite the Confederate defeat, he was promoted to lieutenant general the following month. At the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Jackson commanded the right flank in another devastating defeat of Union forces, this time led by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside.

A Grievous Wound

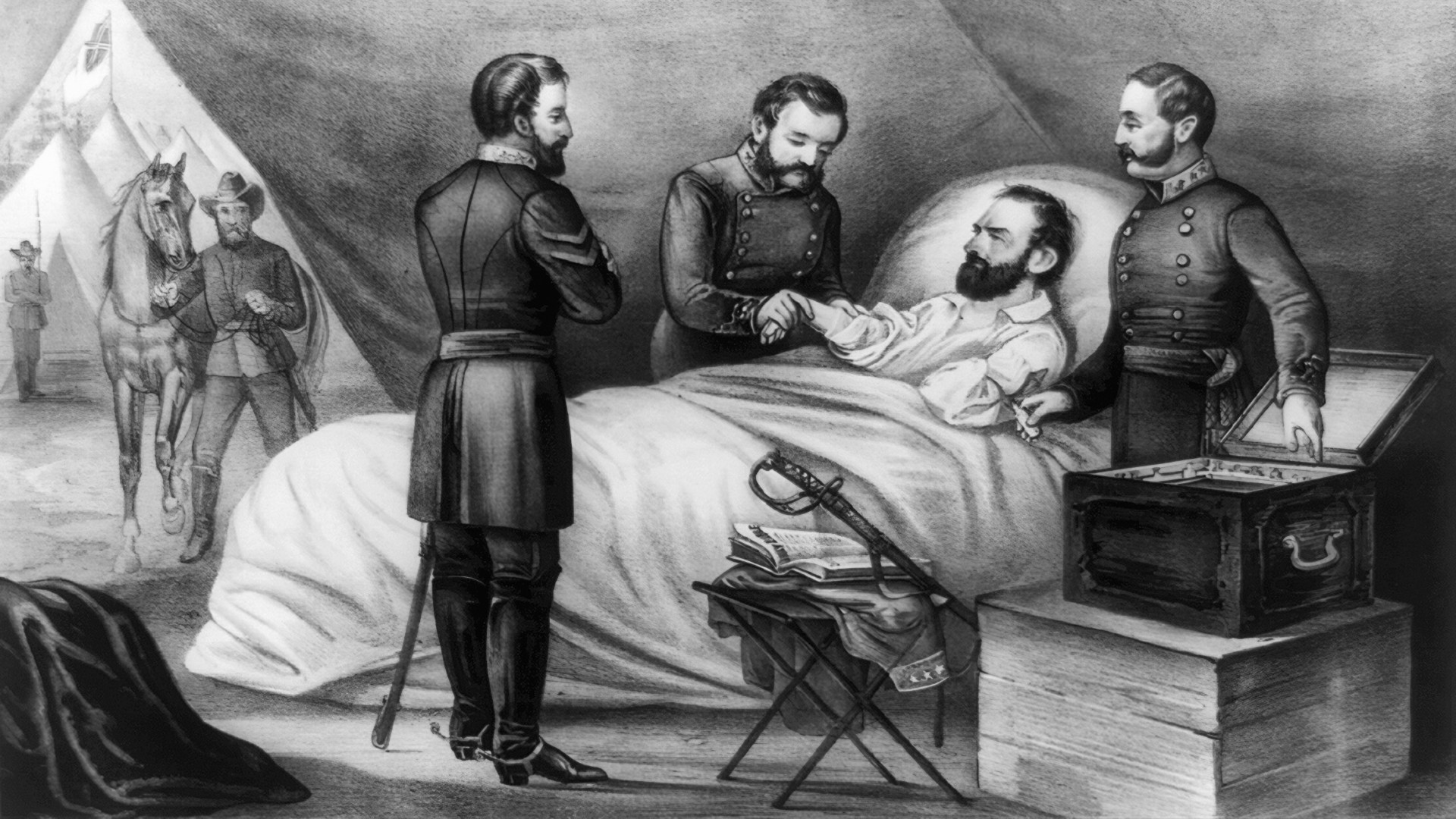

Jackson’s brilliant flanking move at Chancellorsville helped Lee reverse the tide of seeming Union victory and shatter the forces of the new enemy commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. It would be Jackson’s last hurrah. After sustaining a gunshot wound to his upper left arm and a minor wound to his right hand, Jackson left the battlefield supported by two aides. He was then placed on a litter. One of the litter-bearers was shot, causing the general to be thrown painfully to the ground. Jackson was lifted back onto the litter and carried a few hundred yards to the rear, where the 27-year-old medical director of the II Corps, Dr. Hunter McGuire, examined his wounds. “I hope you are not badly hurt, General,” he said. “I am badly injured,” Jackson responded forthrightly. “I fear I am dying. I am glad you have come. I think the wound in my shoulder is still bleeding.”

McGuire observed that Jackson’s clothes were saturated with blood and saw that the wound to the left arm indeed was still bleeding. He applied compression to an artery and called for a light to examine the wound more closely. He found that the bandage had slipped and adjusted it to stop the hemorrhage. McGuire also found that Jackson’s hands were cold, his skin was clammy, and his face and lips were pale—all classic signs of hemorrhagic shock. Jackson, however, admitted no discomfort. He was given morphine and whiskey nonetheless—despite being a lifelong teetotaler—and was removed to a nearby field hospital.

Immediate Surgery

At the hospital, McGuire determined that immediate surgery was necessary. When he informed Jackson, the general replied, “Yes, certainly, Dr. McGuire, do for me whatever you think best.” Chloroform was administered and Jackson murmured, “What an infinite blessing,” as he slipped into unconsciousness. McGuire first extracted a round ball that had lodged under the skin at the back of Jackson’s right hand. It had entered the palm and fractured two bones. Next, McGuire wrote, “The left arm was then amputated, about two inches below the shoulder, very rapidly, and with slight loss of blood, the ordinary circular operation having been made.”

Amputations accounted for approximately 75 percent of all operations during the Civil War. Antiseptic techniques were not yet in practice, and contaminated instruments and non-sterile conditions resulted in many wound infections. Nevertheless, prompt amputations undoubtedly saved many lives by converting traumatic wounds into surgical procedures to improve patient survivability. During the war, surgeons found that amputations performed within 48 hours of an injury were twice as likely to be successful as those performed later. Union records reveal a total of 5,540 upper-arm amputations, from which 1,273 amputees died from complications—a fatality rate of 23 percent.

Jackson tolerated the surgery well despite his earlier significant blood loss. At 3:30 the following morning, Major Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton arrived at the hospital to obtain orders for Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Jackson’s replacement as corps commander. Jackson attempted unsuccessfully to respond. “He tried to think,” reported Pendleton. “He contracted his brow, set his mouth, and for some moments appeared to exert every effort to concentrate his thoughts. For a moment we thought he had succeeded, for his nostril dilated, his eye flashed its own fire, and his thin lip quivered again, but it was just for a moment. Presently he relaxed again, and very feebly, and oh so sadly, he answered, ‘I don’t know. I can’t tell. Say to General Stuart that he must do what he thinks best.”

An Uneven Recovery

Jackson then slept for several hours and appeared to be free of pain when he awoke. At 10 am, however, he experienced a severe and sudden episode of pain in his right side and called for McGuire. Jackson assumed that he had injured his side when he struck a stone or stump during his fall from the litter the night before. McGuire made a careful examination and concluded, “No evidence of injury could be discovered by examination; the skin was not broken or bruised, and the lung performed, as far as I could tell, its proper function.” The pain soon abated.

By 8 pm, the pain had disappeared and Jackson seemed to be doing well. The following day, fearing Jackson’s capture by nearby Federals, Lee ordered McGuire to remove his patient to Guiney Station, 27 miles away. Early the next morning the ambulance set out, and Jackson seemed to tolerate the transfer well. Later in the day he became nauseated and asked that a wet towel be placed on his abdomen. Upon arrival, he felt well enough to take bread and tea.

The house where Jackson was to convalesce already contained several other wounded soldiers, including several with cases of highly contagious erysipelas, a skin infection caused by the bacteria streptococcus. McGuire would not allow Jackson to be exposed to the infection and found him a small building on the grounds that had been used as an office. The general slept well that night and awoke to eat a hearty breakfast.

McGuire dressed Jackson’s wounds and found them to be healing well without signs of infection. Jackson seemed satisfied with his progress and inquired how long it would be before he could return to the field. At 1 am, however, he suffered another bout of nausea and asked a servant to reapply a wet towel to his abdomen.

Jackson did not want to disturb the exhausted McGuire, who awoke to find his patient complaining again of pain in his right side. After examination, McGuire reluctantly concluded that Jackson had “pleuro-pneumonia of the right chest,” presumably secondary to the fall from the litter. The doctor speculated, “Contusion of the lung, with extravasion of blood in the chest, was probably produced by the fall referred to, and the loss of blood prevented any ill effects until reaction had been well established, and then inflammation ensued.”

Making a Diagnosis

On Thursday, May 7, Jackson’s wife, Anna, arrived with their five-month-old daughter, Julia. The sight of her husband’s mangled body and his difficulty breathing alarmed Anna, who said Jackson’s condition “wrung my soul with such grief and anguish as it had never before experienced. He looked like a dying man.” Upon seeing Anna, Jackson smiled and said, “I am very glad to see you looking so bright,” before falling back asleep. When he awoke and saw the look of concern on her face, he said, “My darling, you must cheer up and not wear a long face. I love cheerfulness and brightness in a sickroom.” For his sake, Anna tried to display a happy countenance, but her despair continued to grow.

McGuire had requested the assistance of Dr. Samuel B. Morrison, who arrived late that afternoon. Morrison was a medical school classmate of McGuire’s and a relative of Anna’s. He had treated Jackson before the war and was recognized by the general when he arrived. “There is an old familiar face,” said Jackson, although Morrison was actually five years younger. Morrison was unconvinced that Jackson’s labored breathing and pain in the side were due to pneumonia. He favored a diagnosis of prostration, or complete physical collapse.

Some accounts maintain that Jackson had been ill with a respiratory tract infection prior to the Battle of Chancellorsville, pointing to the fact that he was wearing his raincoat on a warm day owing to chills. However, none of the eight physicians who attended him in the last week of his life mentioned this history or described any sign or symptoms suggesting a preexisting infection. McGuire and Morrison conferred and decided to send to Richmond for Dr. David Tucker, a leading authority on pneumonia. In the meantime, McGuire requested that two other surgeons, Robert J. Breckinridge and John Phillip Smith, join the medical team.

Jackson was restless throughout Thursday night, calling out various orders to his men. “A.P. Hill, prepare for action!” he shouted on one occasion. “Pass the infantry to the front!” he commanded, as well as “Tell Major Hawks to send forward provisions for the troops!”

The four physicians carefully examined Jackson the next morning. The wounds were suppurating, but seemed to be healing normally. There was little they could do, however, to relieve Jackson’s persistent shortness of breath and chest pain. He seemed to be growing weaker by the hour. After another restless night, Tucker arrived from Richmond on the morning of May 9 and confirmed McGuire’s original diagnosis of pneumonia. He recommended cupping. Hot glasses were applied to the afflicted area to “draw the blood.”

“I am not Afraid to Die”

Jackson continued to decline, fading in and out of consciousness. When he awoke in the afternoon and saw several surgeons standing around his bed, he said, “I see from the number of physicians that you think my condition dangerous, but I thank God, if it is His will, that I am ready to go. I am not afraid to die.” Following another difficult night, the general awoke on Sunday, May 10, completely exhausted. It was apparent to everyone that he could not last the day. Anna broke down sobbing and told Jackson that there was no hope for his recovery. Jackson called for McGuire and said, “Doctor, Anna informs me that you have told her I am to die today. Is it so?” McGuire replied that there was nothing further the doctors could do. Jackson paused, then responded, “Very good, very good. It is all right.”

After brief visits from little Julia and Major Pendleton, Jackson lapsed into a coma. He awoke shortly before 3:15 pm and spoke his final, enigmatic words: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The Diagnosis in Retrospect

While McGuire and the other attending physicians all agreed that pneumonia was the cause of Jackson’s death, modern-day analysis raised the more likely possibility of pulmonary embolism. The source of the so-called pleuro-pneumonia was presumed to be a lung contusion incurred during Jackson’s fall from the litter. However, from the distance of a few feet at most, the ribs would have absorbed most of the force of the fall, protecting the underlying lung. There would also have been external evidence of trauma such as bruising in an injury serious enough to result in a lung contusion. Neither McGuire nor the other physicians found any evidence of such trauma.

Pleuro-pneumonia is a medical term that is rarely used today. Pleurisy occurs when inflammation involves the pleura, or outer surface, of the lung. Pleuritic chest pain often accompanies pneumonia, thus the term pleuro-pneumonia. Sir William Osler’s 1892 edition of his classic textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, states: “Pneumonia is a self-limited disease, and runs its course uninfluenced in any way by medicine. It can neither be aborted nor cut short by any means at our command.” Osler went on to say that “the first distressing system is usually pain in the side, which may be relieved by local depletion—by cupping or leeching.” Such treatment was used unsuccessfully on Jackson.

According to the thinking of the day, Jackson’s clinical presentation fit with pneumonia. His physicians cannot be faulted for their diagnosis or treatment, although it should be noted that 19th-century physicians were adept at eliciting the subtle physical signs of pneumonia, such as hearing a cracking sound in the lungs with a stethoscope or finding dullness to percussion of the chest. Neither of these classic signs of pneumonia was found by any of Jackson’s doctors.

In terminal pneumonia, the clinical course typically goes from bad to worse. But in Jackson’s illness, there were two distinct, sudden episodes of deterioration. These occurred on May 3 and May 6, and both were described as being associated with the onset of acute chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and perhaps fever. These symptoms are consistent with pulmonary emboli, which are blood clots traveling to the lungs. Among the numerous complications following amputation of an extremity are nonhealing of the stump, infection, and thromboembolism, or the formation of a blood clot within a large vein. According to McGuire, Jackson’s wound appeared to be healing properly and infection did not seem significant.

It is known today that an amputee is at significant risk for venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism. Immobilization of the patient following surgery can allow the blood to pool and clot within the veins. More dangerous is the formation of clots in the large veins that are tied off during amputation. The tying off of the veins, or ligation, leads to stagnation of blood in the veins, which leads in turn to a thrombus, or clot, which can then travel to the lungs and kill the patient.

Even with today’s advanced technology, it is estimated that as many as half of all pulmonary emboli go undetected by physicians. The current treatment and prevention of thromboembolism is accomplished by the use of blood-thinning agents such as Heparin and Lovenox. Although Stonewall Jackson’s death was unpreventable, given the state of medicine at the time, it is more likely that he died from thromboembolism as a direct consequence of his wound and amputation, than from the indirect cause of pneumonia.

I’m a mostly retired pharmacist and I think you nailed it ! It rings true to me. Excellent article, thank you very much !

The USA is lucky this man died from these wounds. Jackson might have helped the rebels win, if not lengthening the war and causing thousands more to die with his brilliant battlefield command. Don’t forget he was fighting to preserve slavery (state’s rights).