By Mark N. Lardas

The Crimean War is usually considered a Black Sea conflict, but it actually took place on several frontiers of the Russian empire, including the Baltic and White Seas. In the summer of 1854, the Pacific squadrons of three nations—Russia, Great Britain, and France—fought the most unusual and anachronistic action of the war on the distant and forbidding Kamchatka Peninsula.

The ships, tactics, and commanders involved in that battle seemed more appropriate for Admiral Horatio Nelson’s world than the modern age of steamships and railroads in which the battle was fought.

Advent of the Steam-Powered Warship

In the 1850s, steam propulsion was still new. No nation, not even Great Britain, had yet established worldwide chains of coaling stations. Remote stations—and in 1854 no corner of the world was more remote from Europe than the northern Pacific—still relied on sailing warships. The squadrons were small and the ships generally elderly, relics of the period following the Napoleonic Wars. The British squadron had five such ships. Pique, the newest of the sailing ships, had been launched in 1834. The flagship President, launched in 1829, was a copy of the American-made 44-gun President, captured by the British in 1815. Two other ships, Amphitrite and Trincomalee, were completed in 1816 and 1817, respectively. Amphitrite and Trincomalee were both Leda-class frigates, a design that dated back to 1794.

Ironically, both the American class imitated by President and the British Leda class had been intended as those nations’ responses to the large frigates that France had commissioned after the American Revolution. The Americans had gone for large frigates, mounting 24-pounder main batteries. The British Leda-class frigates during the Napoleonic era were rated as 38-gun frigates, carrying a main battery of 18-pounder long guns. This design provided the backbone of the Royal Navy’s cruiser squadrons during the first two decades of the 19th century, but by the 1850s their age had long since passed. Their main batteries were lightened, and they and their sister ships were relegated to remote squadrons and training duties.

The sole English steamship, Virago, was a six-gun paddle wheeler. Launched in 1842, she was rated a first-class sloop and displaced more than the 40-gun Pique. Based on the design of the HMS Gorgon, Virago was one of 18 paddle steamers built for the Royal Navy. She was the only modern warship in either fleet, but like the rest of the squadron, she was past the leading edge of naval architecture. By the start of the Crimean War, the screw steamer was replacing the paddle steamer, with its vulnerable wheel-boxes, in the battle line of modern navies.

Comparing the Fleets

Commanding the English force was Rear Admiral David Price, 64, who came from the same era as most of his ships. He had last seen combat as a midshipman in the Napoleonic Wars and had been on half pay from 1815 to 1834. Between 1834 and the early 1850s, he had spent his time commanding shore emplacements and serving at various administrative posts. By the time he attained the dream of most naval officers—personal command of a squadron of warships—he was ready for retirement. Instead, his first seagoing command in his career saw him leading ships into battle.

The French force was in little better shape. It consisted of four ships, Forte, Eurydice, Artémise, and Obligado.. While their designs postdated the Napoleonic era, they were still traditional wooden warships, sail-powered with smoothbore cannons. Their commander, Rear Admiral Auguste Fevrier-Despointes, had more seagoing experience than Price, including time in the Pacific. A year earlier, in September 1853, he had overseen France’s annexation of New Caledonia and served as its first governor general. Although six years younger than Price, Fevrier-Despointes was unwell. He would die aboard his flagship Forte the following year.

The allied forces dwarfed their opponent. The Russians had just three warships in the Pacific, all sailing vessels: the frigates Pallas and Aurora and the transport Dwina. Aurora, launched in 1833, had spent her entire career in the Baltic. At the outbreak of the war, Pallas and Dwina were in Siberia, while Aurora was en route home from Callao, Peru. Russian land forces were carefully parceled in small garrisons along a coastline that spanned half of the Pacific, from Vladivostok in Siberia to Wrangel in Alaska.

Great Britain and France had little interest in the North Pacific, which was one reason the posting attracted such superannuated commanders—the better leaders were needed elsewhere. For Russia, however, the active frontiers of Siberia and Alaska were on the cutting edge of Russia’s economic growth. With their abundant reserves of furs, timbers, and minerals, these provinces were as rich as they were isolated, and they rewarded hard, active, and competent leaders.

Rear Admiral Evfimii Vasilevich Poutiatine was one such leader. He realized that he could not attack with the forces he commanded, and that—even worse—he could expect no reinforcements from the czar. Accordingly, he chose to guard those positions he felt would be attacked by his foes. He sent Pallas far up the Amur River, using her guns and crew to fill out the garrisons there. He also decided to hold Petropavlovsk, an outpost on the Kamchatka Peninsula. To reinforce it, he sent Dwina with 350 soldiers from a Siberian line battalion, two 68-pounder mortars, and 14 36-pounder long guns. Compared with his opponents’ resources, it was a pitifully small force, but it represented a significant fraction of Poutiatine’s total reserves.

The Port City of Petropalovsk

Established by Russian explorer Vitus Bering in 1740, Petropavlovsk was one of the world’s forgotten ports. The port was named for Saints Peter (Petro) and Paul (Pavlo), the names of the two biggest ships in Bering’s final expedition. Isolated from the Asian mainland by the mountains that form the Kamchatka Peninsula, the desolate port could be reached only by sea. Yet Petropavlovsk possessed an excellent harbor, and the same mountains that blocked land travel sheltered the town from the worst of the subarctic winter weather. Halfway between Vladivostok and Russia’s Alaskan ports, Petropavlovsk was the only way station linking Russia’s Asian and American holdings. Although the town’s early growth was slow, by the middle of the 19th century the port had grown in importance, reflecting Russia’s increased interest in both Siberia and Alaska.

In 1849, the Russian government decided to develop Petropavlovsk as a naval base and make the town its major port on its Asian shore. A lighthouse was built at the entrance of Avachinskaya Bay that year. A new governor, Colonel Major Vasily S. Zavoiko, another active leader, was appointed in February 1850. Zavoiko began a major building program, constructing a wharf, a shipyard, a foundry, and new barracks. These facilities and the capabilities they provided the Russian Navy in the western Pacific made the town an obvious target once Russia found itself at war with France and Great Britain in the spring of 1854.

Zavoiko learned of the war’s beginning that May and immediately commenced to prepare his fortifications at Petropavlovsk. His garrison then numbered fewer than 250 men, but townspeople rallied to defend their tiny piece of Mother Russia. Virtually the entire population of 1,600 people participated in constructing earthworks. In the months that passed between the beginning of the war and the first arrival of the Anglo-French forces in Avachinskaya Bay, no fewer than seven batteries were carved into the steep slopes around the harbor.

A First Repulse of the Royal Navy

The first piece of good fortune for the defenders of Petropavlosvsk came in late June. On June 19 by the Julian calendar then used by Russia (July 1 by the Gregorian calendar used by the West), Aurora slipped unmolested into the harbor. She had departed Callao on the evening of April 24-25, evaded the French and British ships hunting her, and crossed the entire span of the Pacific in less than two months, even though much of her crew was suffering from scurvy.

Seeking refuge, Aurora sailed to Petropavlovsk, anchoring where she could command the approaches to the harbor. Zavoiko had her landward battery removed and distributed among the positions prepared by the governor.

On August 5, Dwina arrived at Petropavlovsk with her soldiers and guns. These reinforcements gave Zavoiko a garrison of 988 men with which to defend his isolated command. Of these, 350 were sailors and 54 were local volunteers. The locals, hardy hunters and trappers, were all expert marksmen and would play an important role in subsequent operations. Dwina anchored alongside Aurora in the harbor, behind a sand spit on which an 11-gun battery had been placed. Aurora could safely cover that battery and the three-gun and five-gun batteries on either side of the port. As with Aurora, Dwina’s guns on the side facing the shore were removed and distributed to the batteries. Four other batteries were placed along the inland approaches to the port.

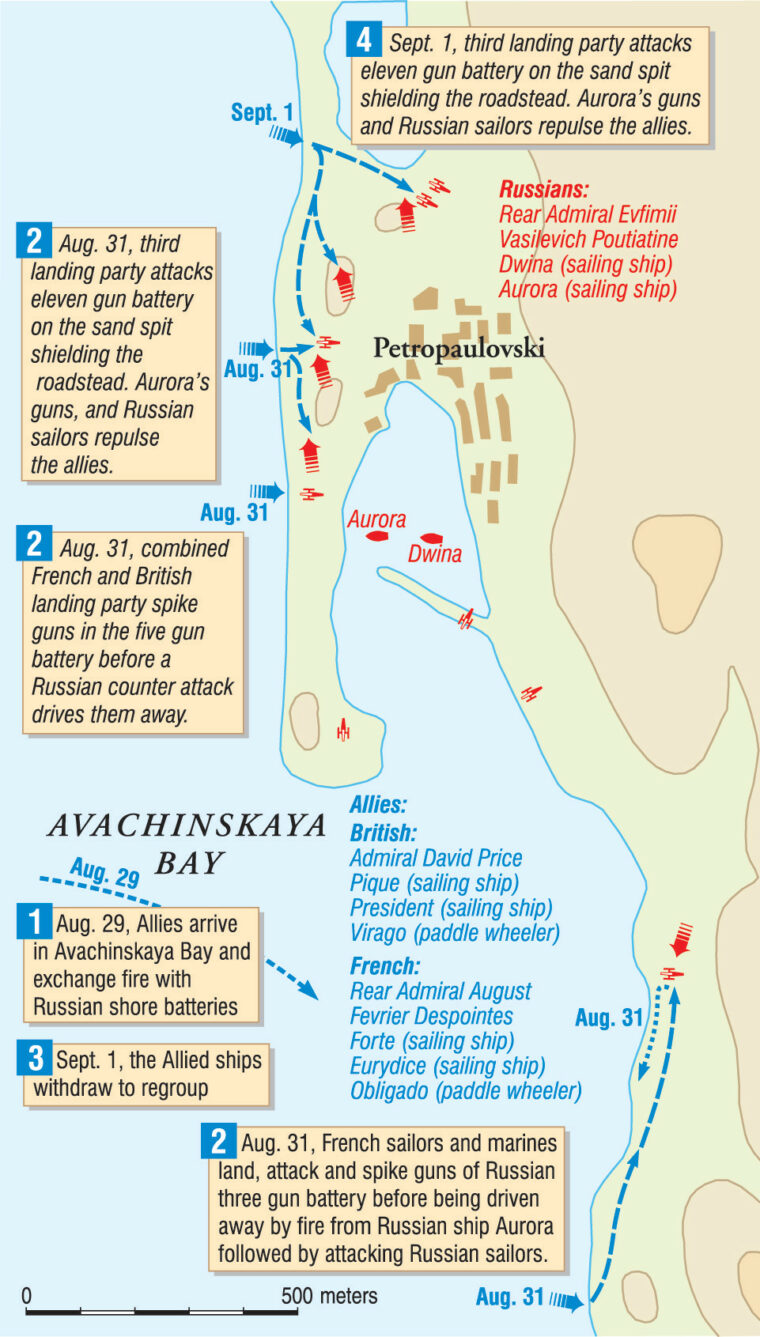

The allied commanders, Price and Fevrier-Despointes, sailed into Avachinskaya Bay on August 29. Unaware that Aurora had gone to ground at Petropavlovsk, the allies earlier had detached Amphitrite, Artémise, and Trincomalee on independent cruises off the coasts of California to show the flag and protect British and French trade from the perceived threat posed by the Russian frigate. This left the invading force with the vessels Amphitrite, Artémise, and Obligado. and their combined crews of 2,600 men.

The allies had put considerably less thought into capturing Petropavlovsk than the Russians had into defending it. Possibly they expected that the mere appearance of their fleet would simply overawe the Russians into surrender. Instead, the Russians greeted the attackers with gunfire, which the frigates returned—albeit at too great a range for either side to be effective. The allies withdrew into the bay to consider their next move..

An Apologetic Death

The next morning they renewed their attack. But as President, Pique, and Forte drew into range, Price excused himself from the quarterdeck, retired to his cabin, and put a pistol to his chest. The responsibility of leading men into battle had proved too much for him—as, apparently, had his marksmanship. Price attempted to shoot himself in the heart, but missed. The bullet instead lodged in a lung, condemning him to a painful and lingering death.

What was intended as high tragedy soon devolved into grim farce. Price’s attempt at suicide left the allies leaderless. The day’s attack was abandoned. As the warships again withdrew into the bay, Price’s officers came to see their dying commander one by one. He apologized to each in turn for his action, explaining that he could not “bear the thought of taking so many noble and gallant fellows into action.” Fevrier-Despointes, too, came aboard President to see his counterpart as he lay dying.

In agony, Price called for the ship’s surgeon to finish the job. Finally Price died, leaving Captain Sir Frederick Nicholson, commander of Pique, as the senior British officer on the scene. Because the Royal Navy had the majority of the forces committed (and because Fevrier-Despointes was ill and disinclined to lead the force), Nicholson now found himself in command of the allied assault.

A Fight for the Russian Guns

Price’s death blighted the ensuing assault. His vacillating on the 29th, followed by his suicide on the 30th, meant that Nicholson was attacking a force well aware of his presence and ready—indeed eager—to repel any invasion. The suicide had rattled British morale. Chaplain Holme of President wrote, “What all will say at home of an English Admiral deserting his post at such a moment we cannot conceive.” Yet Nicholson took the bit and renewed the attack on August 31.

At 8 am, President, Pique, and Forte, towed by Virago, took up positions to bombard the three Russian batteries guarding the approaches to the roadstead. By mid-morning they had silenced them. Led by Virago, 15 boats filled with French sailors and marines landed at the three-gun battery to the right, capturing it. Aurora began firing upon the invaders and sent a party of 200 sailors to repulse the French. The French, in turn, spiked the enemy guns and withdrew under heavy attack.

A combined British and French landing party was sent against the five-gun battery next. Once again the guns were rendered inoperable before a Russian counterattack pushed the invaders out of the battery. A third allied landing party was sent against the 11-gun battery on the sand spit shielding the roadstead. For a third time the Russians, supported by Aurora’s guns, repulsed the enemy. Ten hours of hard fighting had ensued, and both sides were exhausted. Although the batteries guarding the harbor were silenced, the allies could not follow up with an immediate assault on the harbor. Instead, the British and French drew off into the bay to renew the battle the next morning.

While the British and French slept, the Russians labored all night to restore their batteries. By dawn the batteries were again functional. Nonplussed by the renewed resistance, the allied ships withdrew to consider their alternatives. The pause lasted for three days. On September 2, Virago took Admiral Price’s body to Tarinski Bay for burial. During the trip, the steamer picked up three American sailors who had been in Petropavlovsk. The men, apparently deserters from a whaling ship, gave the attackers critical information about the defenses inside the Russian port, including the sizes of the garrison and batteries. They also volunteered knowledge of an easier way into the port than the sea route, promising to lead the allies into Petropavlovsk through a northern road.

The deserters were either fools or knaves. The “unguarded” inland route to the city was covered by three of the Russian batteries—one at the water’s edge on the northern slope of Mount Nikolayevka, a second at the southern flank of the mountain between it and Mount Signalnaya, and a third covering the inland northern road to Petropavlovsk. Ignorant of the arrangement, the British and French held a council of war and agreed to try the sailors’ route. They would attempt a landing near Mount Nikolayevka, then cross over the mountain and attack the town from the north.

Bloody Journey Inland

At 8 am on September 4, a force of 700 marines and sailors was landed near Mount Nikolayevka. The landing spot was also near two Russian batteries, but these were quickly silenced by fire from President, Forte, and Virago. Led by Captain Burridge of President and Captain Grandiér of Eurydice, the landing party moved up the hillside past the abandoned batteries.

The allies broke into three columns as they advanced. Two groups moved up Mt. Nikolayevka, while another began following the northern road to Petropavlovsk, hoping to take the town from the rear. Brush and brambles covered the slope, impeding the advance by the allied units. The garrisons of the silenced batteries had moved uphill ahead of the advancing invaders and were using the thick brambles growing on the hillside to provide cover while they sniped at the attackers. As the British and French struggled up the hillside and down the road to Petropavlovsk, they moved out of range of supporting gunfire from their fleet, losing the biggest advantage they held over the Russians.

Russian fire was heavy and deadly. The sharp-shooting Siberians translated their hunting skills into military purposes with devastating results, concentrating fire on the enemy officers. They killed Captain Charles Allen Parker, commanding the Royal Marines, and wounded no fewer than seven other officers with the landing party. The Russians, warned by the allied bombardment of their batteries, had rushed 300 defenders to oppose the advance. The allied advance faltered as the officers fell, leaving the men leaderless. In the face of stiffening Russian resistance, a retreat to the landing site was ordered. As the French and British began to withdraw, the emboldened if outnumbered Russians launched a bayonet charge, completing the allied rout.

Before the French and British regained their boats, they suffered 208 casualties, killed and wounded. By 10:45 the assault was over. The survivors were once more aboard ship, and the frigates withdrew from the range of the Russian artillery. The allies had now been repulsed on four occasions. When losses from the previous assault on the roadstead were included, the total was nearly 450 casualties, or one-sixth of the total force. Their commanding admiral was dead by his own hand; his French counterpart was ill. Completely dispirited and low on ammunition, the British and French squadrons withdrew from Avachinskaya Bay on September 7. Before quitting the Kamchatka coast, they captured a Russian transport, Stitka, and a small schooner, Avatska, both of which were loaded with stores. It was a poor trade for Petropavlovsk.

Taking the Port

The reverse, as it turned out, was temporary. The following year the Royal Navy returned to Petropavlovsk with a new and energetic British admiral, Rear Admiral Henry William Bruce, in command. In addition to the ships that had attacked the port in 1854, the British committed Trincomalee and Amphitrite, reinforced by the sailing sloops Dido, Encounter, and Barracouta, and the screw steamer Brisk. The three French warships were reinforced by another sailing frigate, Alceste, and Admiral Fourichon had replaced Fevrier-Despointes, who had finally succumbed to illness.

Instead of strengthening and consolidating the defenses of the port, the governor-general of Eastern Siberia, Muraviov-Amursky, ordered the port evacuated on March 27, 1855. The situation in Siberia had grown more desperate after Pallas wrecked in the Amur River during the previous winter. Muraviov-Amursky knew the Russian Navy could send no reinforcements, and that the allies had more ships on the scene. Petropavlovsk was doomed.

Zavoiko obeyed the order with his characteristic energy, cutting paths through the ice covering the harbor to facilitate evacuation. He buried the garrison’s guns or loaded them, along with any useful supplies, aboard Aurora and Dwina. By mid-April, with the port still icebound, the Russians were gone. The batteries were empty of guns, the military storehouses were bare, and the treasury was broke. Civilians removed to the village of Avatcha, inland on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Bruce had sent Encounter and Barracouta to watch the port, starting in early February, but bad weather forced the sailing vessels to stand well away from the harbor. Taking advantage of the snow and fog, the two Russian ships slipped past their guardians undetected and unsuspected. On May 30, the 12-ship allied squadron entered the harbor cautiously despite the lack of enemy fire. They found it almost entirely deserted, except for two Americans and their French servant.

The British and French destroyed the port’s arsenals, batteries, and magazine; burned the barracks, bakery, treasury, and other public buildings; and sank a whaler they discovered in Rakovia Harbor. They spared the civilian buildings in the town, including a warehouse claimed by the two Americans. Lacking any further incentive to remain in Kamchatka, the allies then left. They scoured the Siberian coast for the Russian forces that had evacuated Petropavlovsk and eventually found them. Aurora, Dwina, and four merchant ships were anchored well up the Amur River, positioned behind a shallow bar. Sheltered by their own guns and shore batteries, they proved too formidable an opponent to attack. The allies left them there, unmolested, until the end of the war.

Lessons from the Battle

The Battle of Petropavlovsk, forgotten in the West, is still commemorated in Russia as an outstanding naval victory. The Russians named one of their first ironclad warships Petropavlovsk, and kept a ship of that name in commission throughout the remainder of the life of czarist Russia. A later Petropavlovsk was sunk at Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War, and a third Petropavlovsk was one of the four Gangut-class dreadnoughts built by the Imperial Russian Navy before World War I.

The Russians are entitled to celebrate. Although the battle was a petty action in an ignored theater of a minor war, the Russian defenders of Petropavlovsk nevertheless fought bravely and skillfully, succeeding against a superior opponent. The Russian retreat the following spring was equally skillful, denying the allies their chance for revenge. Another factor encouraging fond Russian memories is that the Battle of Petropavlovsk was one of their rare naval victories in the 19th century—and a victory against the mighty Royal Navy, no less. Although the Russians were hardly facing a commander of Lord Nelson’s abilities during the battle, it was still a victory to be savored.

For the Royal Navy and the French Navy, Petropavlovsk was a cautionary tale about the declining effectiveness of peacetime navies. A good share of the blame for the allied loss lay in poor leadership. Both Admirals Price and Fevrier-Despointes belonged at home, in retirement, not commanding remote units of their respective navies for the first time in their lives. Price simply could not cope with the responsibilities of command. His suicide was less a cause for condemnation than for sympathy. Fevrier-Despointes was too ill to exert an active part in the activity, allowing command to devolve to a senior captain.

The British captains exercised more energy and bravery than judgment. They deferred to Price until his death. While this was to be expected in the 19th-century Royal Navy, they did not rise to the opportunity offered to them after his death. Instead of gathering intelligence and developing a plan that took advantage of Russian weaknesses, Nicholson simply charged into the port on the first day of his command, then allowed the Russians to rebuild the batteries the British and French had destroyed at the cost of more blood and ammunition. Finally, the landing on September 4 was done without adequate reconnaissance or, indeed, any planning at all beyond the point at which they landed.

After the War

The Crimean War ended in March 1856. Aurora left the Amur River that July and sailed back to Kronstadt, finally arriving after nearly a year at sea. She never saw service again, and was scrapped in April 1861. Admiral Poutiatine became the Russian envoy to Japan in 1858. Zavoiko was promoted to general by the end of the Crimean War, and he later helped found Vladivostok.

Petropavlovsk took a long time to recover from the war. Mainland ports appeared. Nickolayevsk-on-Amur became the principal Russian port on the Pacific coast before being supplanted by Vladivostok in 1871. Russia sold its Alaskan lands to the United States in 1867. Instead of being an important way station on the trade route to North America, Petropavlovsk had become the extreme eastern end of the Russian empire. By 1890, the port had shrunk from 1,600 to 506 inhabitants. Ten years later it only held 383 people. It took another Pacific war to restore the town to its former status.

Of the allied ships involved in the battle, most passed out of the battle fleet after the Crimean War. In many ways, the Battle of Petropavlovsk was the last act in the age of fighting sail. While pure sailing vessels would still see service as warships for the next 15 years, they served in supplementary roles after 1856. The wooden warship’s time was also limited, even for screw steamers. The year 1860 saw the launch of HMS Warrior, an iron-hulled, armored, steam warship. A year later, the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia/em> sounded the death knell of the sailing warship by destroying two wooden sailing frigates in Hampton Roads, Virginia. Only another ironclad, USS Monitor, prevented the destruction of rest of the United States Navy’s wooden warships in those waters.

One of the British ships in Price’s squadron, HMS Trincomalee, still exists. Used as a harbor vessel after 1871, she became a training ship in 1903. For the next 83 years, generations of boy sailors learned the ropes on her top deck. By 1983, this type of school ship had become obsolete, but because of her age (and an increasing fascination with the age of the sail), the ship was restored as a museum in Hartlepool, in northeast England, where visitors can see her today.

One odd echo of the battle remains. As with most navies, the Russian Navy reuses the names of ships that have fought illustrious actions. When the wooden frigate Aurora retired, her name was taken by another Russian warship, a light cruiser launched in 1897. The name proved as fortunate for the cruiser as for the earlier frigate. The cruiser Aurora was one of the few Russian participants that survived the Battle of Tsushima Strait. Then, in 1917, stationed in Petrograd, she fired the shots that launched the October Revolution. Surviving World War II in Leningrad, the cruiser was preserved as a monument to the Russian Revolution. Today, she is a museum ship in the Nevka River, the only surviving warship of the Imperial Russian Navy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments