By Eric Niderost

On March 12, 1689, James II, recently deposed king of England, landed in Ireland in a last-ditch attempt to regain his throne. His arrival at Kinsdale was greeted with a fair amount of enthusiasm, and he was accompanied by an impressive array of French officers and shiploads of military stores. Catholic Ireland had suffered political repression under Protestant English rule, and many Irishmen hoped that James, as a fellow Catholic, would be the means of throwing off the English yoke once and for all.

James had been deposed in 1688, in what the English were calling “the Glorious Revolution,” after a reign of only three years. The trouble began when James, brother of the late Charles II, attempted to assert his absolute authority under the widely discredited divine right of kings. This assertion of religious and political autonomy quickly caused James to run afoul of Parliament, which had already deposed and executed one king—his grandfather, Charles I—for just such prideful effrontery. To make matters worse, the king began appointing Catholics to various positions of power in the government and the army—actions which were in violation of the Test Act. When Parliament demanded that the Test Act be enforced and Catholics dismissed from their new posts, James abruptly disbanded the lawmakers, leaving him to rule in the absolute manner to which he believed himself entitled.

For many Englishmen, the last straw came when Queen Mary gave birth to a son. This prince, later known as the “Old Pretender,” would be raised in the Catholic faith, and many of the nation’s Protestants feared that Stuart absolutism would continue indefinitely into the future. English political leaders privately invited James’s Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch consort, William of Orange, to come over from the Continent and depose the king. The treasonous invitation was accepted with alacrity.

William and Mary Take the Crown

William of Orange, the Stadtholder of the United Provinces, commonly known as Holland, had strong claims to the English throne—at least from the Protestant point of view. William’s mother had been a Stuart; in fact, James was William’s uncle, and his wife was his own first cousin. On November 5, 1688, William landed in Torbay in Devon. James, abandoned by all but his loyal Catholic retainers, fled into exile in France.

The Glorious Revolution had been successfully accomplished, and William and Mary accepted the crown of England as joint monarchs. There were, however, certain strings attached. The royal couple had to agree to a Bill of Rights mandating, among other things, that Parliament be summoned regularly and that taxes not be levied without its prior consent. The Bill of Rights limited kingly power and, in effect, established parliamentary rule.

King Louis XIV of France, as the most powerful Catholic monarch in the world, welcomed James with open arms. Every courtesy was extended. The deposed monarch was given a handsome allowance of 200,000 francs a month and granted the Palace of St.-Germain-en-Laye, 11 miles northwest of Paris, as his permanent residence. James, for his part, seemed tired of the political fray and eager to accept the delights of a well-deserved—if forced—retirement. But the king of France had other things in mind.

Le Roi Soleil and James II Plan for War

Louis XIV was le roi soleil, the Sun King, whose power and magnificence was admired as well as hated throughout the Continent. France was at the height of her power, both politically and culturally. French fashion, architecture, and art were slavishly copied. The French language was the lingua franca, the language of diplomacy, of Europe, the language of diplomacy. But Louis XIV was not content with mere cultural dominance—he also desired French political hegemony. The Sun King wanted France to expand to the Rhine, its “natural borders,” and also to bring the Netherlands into the Gallic orbit. The Dutch, with characteristic hardheadedness, were playing David to the French Goliath, at one point opening the dikes and flooding their own homeland in an effort to prevent the passage of rampaging French armies.

It was against this backdrop of European rivalries and power politics that Louis suggested to James that he go to Ireland and win back his throne. Conditions there seemed favorable for an armed revolt, and Ireland was the traditional “back door” to Britain. Gradually, James warmed to the idea. Ireland could be a stepping stone to an eventual return to Scotland and, ultimately, to England. The more he thought of it, the more he was convinced that the plan could succeed.

James had a major ally in Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnel, who still controlled the recently disbanded English army in Ireland. Tyrconnel, James’s former viceroy in Ireland, began sending a stream of letters to James urging immediate military action. Tyrconnel felt that if an attempt was made soon, all Ireland—even Protestant Ulster—would fall into the king’s hands like a ripe plum. Louis XIV, in turn, promised to be generous, and proved true to his word. James’s Irish expedition consisted of 10 ships laden with arms, ammunition, and equipment for 20,000 men. At this point, no French troops were requested, only the tools to create an indigenous army. Tyrconnel promised James that thousands of Irish-Catholic gentry and peasants would provide the raw material for such a force.

James was provided with a war chest of 200,000 livres a month to pay for his troops, as well as a personal allowance of nearly 2 million livres. Louis XIV, playing the role of le grand monarch to perfection, magnanimously gave James his own personal cuirass and weapons so that he would “appear on the field as a king should appear.” He bade James a fond farewell, telling him, “I am deeply grieved at parting with you, but I hope never to see you again.” In other words, Louis hoped that James would not return to France as a failure.

James was accompanied by a hundred or so French military officers, including engineers and artillerymen. They would form the professional foundation upon which James—at least in theory—would build an Irish army. It is significant that Louis made no effort to assign his top generals to the Irish enterprise. To him, Ireland was a sideshow to his greater continental ambitions. The French king knew that his recent aggression against Germany was bound to create an alliance against him and that William of Orange would more than likely be the architect of such an alliance. Trouble in Ireland might well distract and divert William from intervention on the Continent. How could William concentrate on France when there was a threat in his rear from his own father-in-law, the previous king of England?

Invasion of the Isles

James landed on the southeast coast of Ireland with no opposition and was greeted warmly by Tyrconnel and forces loyal to the Stuart king called Jacobites, after the Latin form of “James”. In the early weeks after James’s arrival, Protestant opposition collapsed like a house of cards, although there were pockets of stubborn resistance. James moved north to Dublin, where he was greeted with wild acclaim as the first English monarch to visit the Emerald Isle since the ill-fated Richard II some 300 years earlier.

Almost immediately, there were differences of opinion over how James should best proceed. The king was a man in a hurry, eager to reclaim the English crown as quickly as possible. He wanted to press on and secure Ulster, the largely Protestant part of Northern Ireland, then send troops over the Irish Sea to Scotland. Once in Scotland, he could count on support from the fierce Highland clansmen. James then intended to ask for French troops to invade England from the south. Acting in concert with his Gallic allies, James would move into England and cause a rising of English Jacobites. Caught between two fires, the Williamite cause would soon be immolated—or so James hoped. Tyrconnel took an opposing view. He felt that Ireland should be firmly secured first. Above all, the Irish Jacobites needed a trained army, and that would take time. James balked at Tyrconnel’s suggestions, and plans went forward for an immediate advance on Ulster. James’s inherent vacillation—first hasty and bold, then slow and overly cautious—would prove to be his ultimate undoing.

The port of Londonderry (now Derry) was the main center of Protestant and Williamite resistance. When James appeared in all his regal majesty, the city refused to open its gates to him, even after promises of pardon and religious freedom. A prolonged siege began, one that quickly became part of a powerful Protestant folklore that still resonates to this day. Besieged by land and blockaded by sea, Londonderry began to starve. Soon, residents were reduced to eating dogs and cats, but their will to resist was stiffened by the fiery exhortations of Protestant cleric George Walker, who coined the timeless catchphrase, “No Surrender!”

After a four-month siege, three Williamite supply ships managed to break the blockade and bring food to the beleaguered city. The relief of Londonderry boosted the Protestant cause and handed James his first major setback. Not long after the siege was lifted, William dispatched a 10,000-man army to Ireland under the command of 75-year-old Marshal Friedrich Herman Schomberg, a veteran campaigner who had seen service in the Thirty Years’ War half a century earlier. Schomberg had been a marshal of France until he was exiled during the recent pogrom against French Huguenots (Protestants). He was a competent if not overly energetic general, but seemed reluctant to come to grips with the enemy, at least with the troops at hand, whom he found to be ill-trained, badly armed, and poorly led. “The lions in Africa are not more barbarous,” he said of his new officers. Soon winter descended, effectively shutting down all military operations until the coming of spring, and both sides retired into their disease-ridden winter quarters.

Determination in the Jacobite Ranks

The two armies rested and tried to build up their forces for the looming contest. On the whole, James frittered away his precious time. The Jacobite army only had around 4,000 trained soldiers in its ranks. The rest were raw recruits, scarcely better than a rabble in arms. The Jacobites were strong, sturdy peasants, inured to hardship and brave as lions, but they sorely needed training, discipline, and proper equipment. Most of the equipment came from France and not all of it was good. François Michel, Marquis de Louvois, was the French minister of war, directly responsible for supplying arms to the Jacobites. Wanting to reserve the best weapons for French troops, Louvois sent shiploads of pikes and matchlock guns to Ireland. By 1690, matchlocks were slowly being replaced by flintlocks, which had a more reliable method of igniting a gun’s powder charge. Pikes were also becoming obsolete, replaced first by plug, then later, socket bayonets. Even then, some of the Jacobite soldiers were forced to arm themselves with farmer’s scythes and wooden stakes instead of pikes.

Captain John Stevens, an English Jacobite serving in Ireland, was puzzled at the army’s lack of discipline. Speaking of the Irish recruits, Stevens commented: “They will follow none but their own leaders, many of them as rude, as ignorant and as far from understanding any rule of discipline as themselves. This [will be] the utter ruin of the army.” National jealousy and ethnic prejudice tore at the fabric of the Jacobite force. The Irish and English nursed deep prejudices against the French, which all too often came to the surface and caused friction. James made things worse by appointing far too many English Catholics to the best civil and military positions to suit Irish taste. French officers were pushed into the background, lest they gain distinction over their Irish and English colleagues.

Nevertheless, in the winter of 1689-1690 the Jacobite cause in Ireland seemed bright. Jean Antoine de Mesmes, Comte d’Avaux, was Louis XIV’s representative at James’s court. At first, D’Avaux was pessimistic, noting the king’s lethargy and the periods when, mesmerized by his own dreams of regaining the English throne, he seemed out of touch with reality. But D’Avaux still saw how valuable James could be to the overall French cause against William. He urged Louis to continue his support, and acting on D’Avaux’s advice, the king dispatched five regiments of crack French troops to Ireland. (Actually, only three regiments were French; the others were mainly—and ironically—Protestant Walloons from Belgium. Nevertheless, they were welcome additions to the Jacobite army, providing much-needed backbone to the green and unwieldy force.)

William’s Arrival in Ireland

From the French point of view, things were going particularly well. William’s campaign plans against the French had been put on hold, much to the new monarch’s frustration and chagrin. James was a threat that had to be dealt with first, whatever the cost. William could not attend to affairs in Europe when James might invade England in his absence. William admitted as much when he wrote to an old friend, the prince of Waldeck, one of the few people in whom he confided. “I am in despair,” the English king wrote, “when I think I can be of no use to the common cause [the Grand Alliance] while I am in Ireland.” William professed himself deeply dissatisfied with Schomberg’s performance thus far. The old man was competent and loyal, but reluctant to give battle. He was always complaining, William said. The king would have to go to Ireland himself. He hoped that his physical presence would serve as a talisman of victory and give new life to the Protestant cause.

Events soon proved William correct. He landed at Carrickfergus on June 14, 1690, with an armada of some 300 ships carrying 15,000 troops, 1,000 horses, and 40 pieces of artillery. William also had a war chest of some 200,000 pounds to finance the expedition. The new troops, when added to the ones already serving under Schomberg, boosted the Protestant forces to 36,000 men. Included among the reinforcements were 6,000 mercenaries from Denmark, led by the German-born Duke of Wurttemberg-Neustadt. In another irony, many of the mercenaries were Catholics, and some were even Irish.

Immediately after his arrival, William hurried north to Belfast, where he was greeted with wild acclaim. As word spread, bonfires were lit throughout Antrim and Down. The dour Dutchman William was transformed into a rallying point and symbol of the Protestant cause in Ireland.

“If You Escape Me Now, the Fault Will be Mine”

James, of course, realized that William’s arrival constituted a grave threat, but he was typically unsure how to deal with the situation. One of his new advisers, General Antonin Nompar de Caumont, Comte d’Lauzun, counseled caution and retreat. Tyrconnel, usually more aggressive, also advised caution. They suggested that James follow a long-standing Irish policy of trading space for time. If the Jacobites retreated to the south, they could leave fortified towns and castles in their wake. William would have to besiege each town in turn, wasting precious time and resources.

But James was an inveterate gambler who liked to chance everything on one throw of the dice. He decided not to retreat, but to give battle as soon as possible. The Jacobite army would meet William in defensive positions along the south bank of the Boyne River, the last major natural obstacle barring William’s progress to the southern part of Ireland. The river, running east to west, was influenced by tides from the Irish Sea, making some points fordable at low tide. Nevertheless, the Boyne would serve as a “moat” to protect the Jacobite army and prevent William from capturing Dublin, 30 miles to the south.

James positioned his army along a loop of the Boyne, about four miles west of Drogheda. The Jacobite center rested in the village of Oldbridge, in the uppermost top of the loop. River lines are not always so secure, and positioning the army behind the river’s concave arc left it exposed to enemy enfilade fire. Moreover, Oldbridge was not the only ford in the area—something James was about to discover to his chagrin. The Jacobite army’s greatest disadvantage was James himself. In his youth he had been a competent soldier, having served with both the French and Spanish armies, but as a general he was weak-willed and indecisive, more willing to respond to events than to force them. This indecisiveness and passivity was a sure prescription for failure.

The Protestant army arrived at the north bank on June 29. William and his staff reconnoitered the position and trained their glasses on the Jacobite host just across the river. When one officer dismissed the Jacobites as a “petite army,” William replied that there were dips and folds in the surrounding countryside—James no doubt had more men than was readily apparent with the naked eye. Nevertheless, William was happy to bring James to bay at last. “I am glad to see you, gentlemen,” he said, half to himself, speaking to the enemy across the way. “If you escape me now, the fault will be mine.”

William Nearly Killed

The fighting began with an artillery duel between the opposing forces. Cannon were relatively crude, cumbersome pieces in the 17th century, massive bulks of iron and bronze that were difficult to transport. Williamite six-pounder cannon began firing at Oldbridge, the rain of solid shot damaging several buildings in the village. Jacobite artillery flamed in counterbattery. During a lull in the cannonade an incident occurred that nearly altered the course of European history. William and his staff decided to have lunch along the river bank, even though the enemy was just across the Boyne. William, usually clear-headed and not one to take undue risks, may have consented to the picnic as an act of bravado and defiance to set an example for his men.

On the other side of the river, near rubble-strewn Oldbridge, the Jacobites had two 6-pounder cannon concealed behind a hedge. When the artillery officers trained their glasses across the river, William’s entourage could be plainly seen. In the middle of the cluster of men they spied a stooped figure wearing an elaborate wig that fell in great curls to his shoulders. Looking closer, they caught the sparkle of a metal star on the man’s coat, the Order of the Garter. They could scarcely believe their eyes or trust their luck—this was William himself, within easy range of their guns.

The two cannon fired a salvo of solid shot just as William and his entourage mounted their horses. The first cannonball struck the horse of Prince George of Hesse, while the other grazed William’s right shoulder, ripping the sleeve as it hurtled past. The king, surprised and momentarily shaken, slumped over the neck of his horse. His courtiers were transfixed with horror—had the king been mortally wounded?

Word spread rapidly that William was dead, but the monarch had been only slightly wounded. Once he recovered from the shock, he made light of the incident. “No nearer,” he joked as his wound was dressed and his injured arm put into a sling. Had the cannonball passed a few inches to the left, William would have been killed and the entire history of Ireland, Britain, and perhaps all of Europe would have been profoundly altered.

The Battle of the Boyne

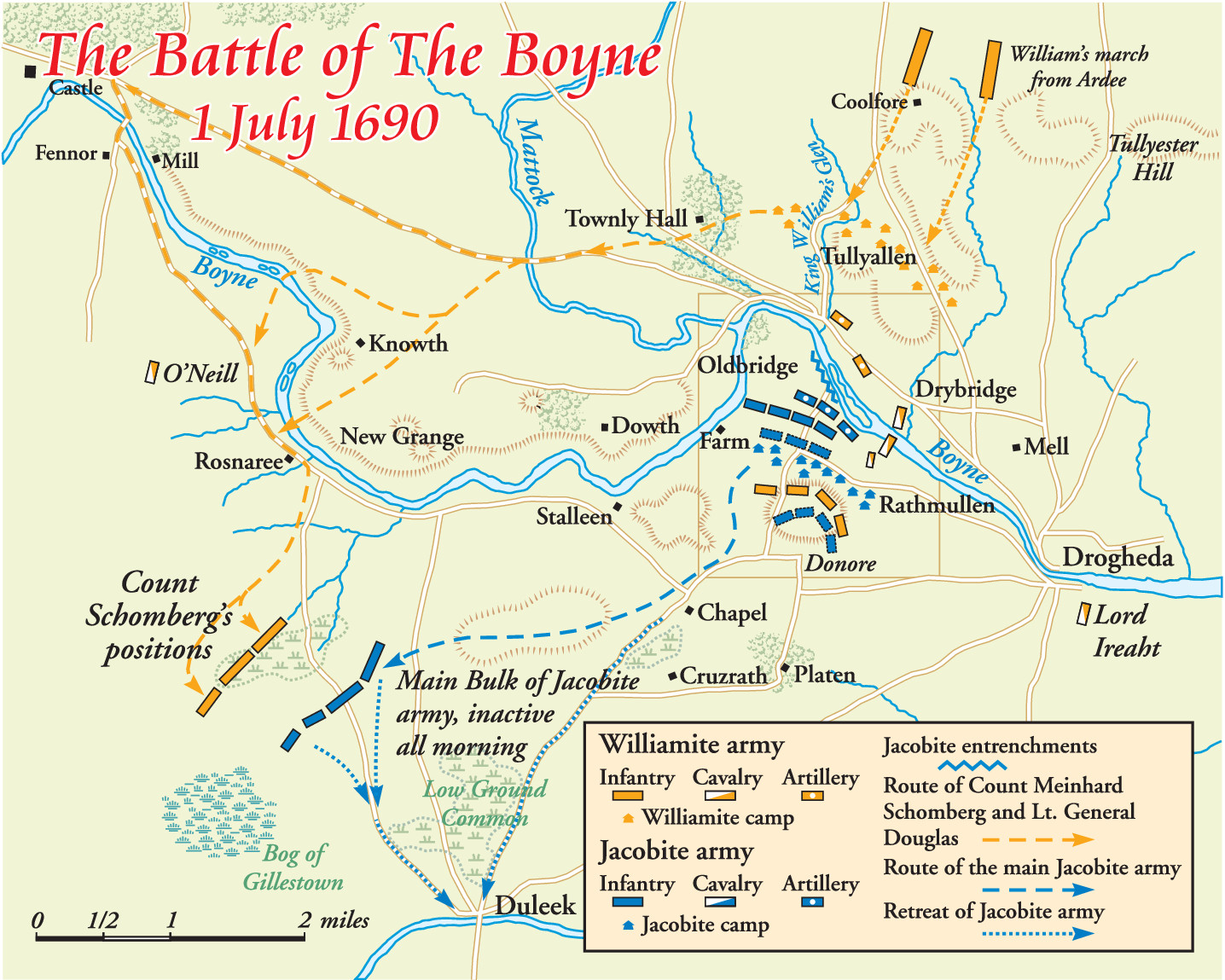

Following his close call, William convened a council of war to discuss the battle plans for the next day. After much wrangling, a simple plan was decided upon. The main Williamite attack would be on the enemy positions at Oldbridge. Meanwhile, a strong diversionary attack would take place at Rosnaree, on the Jacobite left, in an effort to distract James from the main effort. With any luck, the Stuart monarch would split his force and weaken his center.

The Battle of the Boyne began in earnest in the early morning hours of Tuesday, July 1. A spectral mist clung to the green earth, but soon burned off to reveal a pleasantly warm summer’s day. Count Meinhard Schomberg, the 49-year-old son of the old marshal, was dispatched with 3,000 men to make a diversionary attack on the Jacobite left at Rosnaree ford. Rosnaree was held by only one regiment of Jacobite dragoons under Sir Neil O’ Neil. The dragoons were dismounted, standard practice for the period. Dragoons were mounted infantry, not cavalry, and the men used their horses primarily for mobility. Meinhard’s advance guard of grenadiers came under fire as they deployed and attempted to cross the ford. The younger Schomberg followed up by sending a company of dragoons and a regiment of Huguenot horse to support the grenadiers. Seeing the rival horsemen, O’Neil remounted his men and ordered a full-blown charge.

It was a brave but futile gesture. O’Neil’s dragoons were quickly overwhelmed, their formations broken by the sheer weigh of enemy numbers. Over 50 Jacobite troopers were dumped from their saddles, including the mortally wounded Sir Neil. The Jacobite dragoons were destroyed, but they had gained some time—about an hour—for James to react to the threat. Unfortunately, the king overreacted to the threat on the left. It was James’s only direct contribution to the battle, and it proved a fatal decision. Worried that the Rosnaree attack was William’s main effort, James sent the entire French Brigade, troops under Colonel Patrick Sarsfield, and six guns to plug the perceived break in his lines. About two-thirds of James’s army was dispatched to Rosnaree, including some of his best fighting units. Eventually, James rode over to the left himself, in effect abandoning the remaining third of his army to its fate.

Meinhard Schomberg, his diversionary task succeeding beyond his wildest dreams, sat tight for the rest of the day, guarding the southern bridgehead over the Boyne but doing little else. The ground at Rosnaree was too marshy for any major action, but James was too obtuse and befuddled by the sudden weight of military responsibilities to realize this obvious fact. To all intents and purposes, James and the bulk of his army had taken themselves out of the strategic picture. While James waited for something to happen on the left, the battle was going to be decided at Oldbridge.

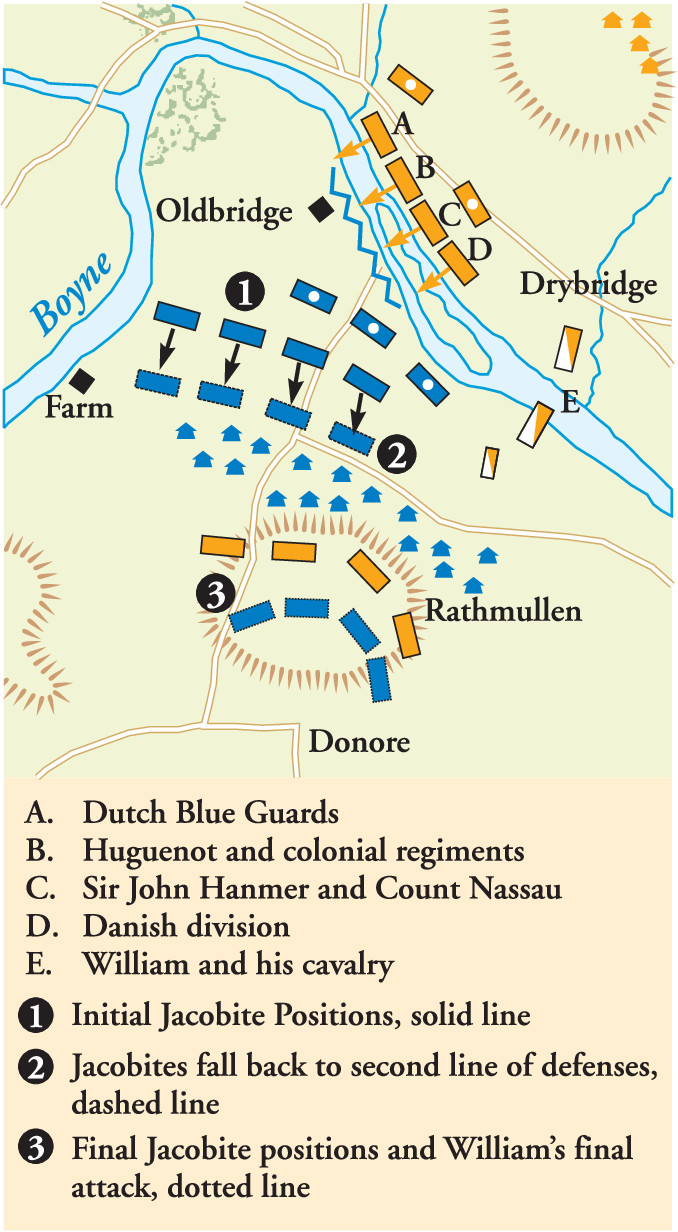

“Lilibulero”: The Crossing of the Boyne

At 10 am, William launched the main attack across the Boyne at Oldbridge. The assault was spearheaded by the elite Dutch Blue Guards. They moved forward, drums throbbing and fifes squealing a rousing tune. Many recognized the music as “Lilibulero,” the signature tune from William’s 1688 invasion of England. The Blue Guards were a magnificent sight, dressed in blue coats with wide orange cuffs, orange breeches, and bright orange stockings—the color, both literally and figuratively, of William’s House of Orange-Nassau. The Blue Guards were armed with the latest flintlock muskets, topped by socket bayonets. They were all tall men, but as they waded into the Boyne, the deepening water and swift currents forced them to raise their muskets above their heads. Eight to ten abreast, they thrashed across the waist-high river and reformed on the south bank. Two French Huguenot regiments followed them across.

Inside the village of Oldbridge, the Jacobite regiments dug in behind the houses, hedges, and low walls of the battered hamlet. The Duke of Tyrconnel, left in charge of the center in James’s absence, sent the Royal Regiment and Foot Guards to Oldbridge in support. The Catholic defenders opened a heavy but ineffectual fire. Part of the problem lay in the fact that most of the Jacobite defenders were armed with matchlocks, inaccurate even by 17th-century standards. The matchlock’s rate of fire was slower than the flintlock, and the coils of match cords were cumbersome and confusing to men ill-trained in their use.

The Blue Guards, having emerged from the water, quickly got into formation to charge. When all was ready, they leveled their flintlocks and delivered a powerful volley into the Catholic ranks. Muskets gouted smoke and flame, and before the acrid cloud could dissipate, the Guards launched a bayonet change against the Oldbridge defenders. The front ranks were held by pikemen, but their long, unwieldy weapons were not designed for close-quarter combat. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued, with little quarter asked or given. The Blue Guards found themselves grappling with the Jacobite Foot Guards. At one point, Jacobite Major Thomas Arthur seized a pike from one of his men and plunged the weapon into the body of a Dutch officer. As the Dutchman crumpled to the ground, impaled and bleeding profusely, a Blue Guardsman avenged his officer by firing point-blank into Arthur’s chest.

“Oh, My Poor Guards!”

After a hard and bloody fight, the Jacobites gave away and were forced to fall back. The Blue Guards secured Oldbridge, then moved onto the fields just beyond. Additional Williamite units forded the Boyne in the footsteps of the Blue Guards. One English regiment crossing that day, Herbert’s Regiment, won its first battle honor on the Boyne. Later, this regiment would become the famous Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

The Duke of Tyrconnel saw what was happening and ordered the Jacobite cavalry forward to stem the Williamite tide. Leading the charge was 19-year-old James FitzJames, the duke of Berwick, who was the illegitimate son of James II. The young man would distinguish himself at the Boyne and go on to carve out a successful career in the French army. The Dutch Guards reacted coolly to the cavalry assault, unleashing a series of disciplined volleys into the oncoming horsemen, then forming squares that bristled with bayonets. The Blue Guards fired by platoons, a rolling wave of lead that emptied many saddles. For a time the Guard squares were blue-and-orange islands in a seething Jacobite sea, prompting William to exclaim, “Oh, my poor Guards! My poor Guards!”

It may have look bad from across the Boyne, but the danger was more apparent than real. The Blue Guards sent the Jacobite horsemen packing with heavy losses, and more and more Williamite regiments continued to cross the Boyne every minute. Richard Hamilton, one of the Jacobite commanders, led a squadron of 60 men forward, the sheer gallantry of the effort seeming to augur success. The Jacobite troopers briefly disordered a couple of Dutch line regiments, but soon fell prey to enfilade fire. Hamilton withdrew to his own lines, returning with only 12 of the original 60 men.

“Do You Not Know Your Own Friends?”

The Jacobite cavalry refused to give up, and more squadrons rode into the fray. They enjoyed a few local successes; at one point the aged Marshal Schomberg was unhorsed and fell heavily to the ground, badly wounded by several saber cuts. A young Jacobite officer rode up and discharged his pistol into the back of the old general’s head, killing him instantly. Hearing of Schomberg’s death, William decided to commit the Danish Division, 7,000 well-equipped troops, procured from King Christian V of Denmark. The addition of these splendid soldiers was sure to tip the scales in William’s favor. William also decided to cross the river himself, an act that almost cost him his life.

The multinational nature of the conflict produced much confusion within the acrid clouds of dirty-white powder smoke. The Danes wore green coats, the Dutch wore gray and blue coats, and the English wore red coats. This was bad enough, but the Jacobites were clothed in similar fashion. The kaleidoscope of colors produced many casualties from friendly fire, despite the fact that both sides wore special “field signs” that day—green sprigs for the Protestant forces, white slips of paper for the Catholics. William himself was almost a victim. At one point, a battle-crazed trooper approached the king of England, aiming a pistol directly at his head. William coolly knocked the weapon aside, exclaiming, “What! Do you not know your own friends?”

For all its dangers, the battle was a tonic for William, making him seem like an entirely different person. The normally taciturn monarch grew animated and loquacious, exhorting and inspiring his men with his presence. After three hours of hard and bloody fighting, the Jacobite army around Oldbridge could take no more. Outgunned and outgeneraled, they began to give way. About 2 pm, James, still near Rosnaree, received a message that his soldiers at Oldbridge had been defeated. His advisers urged him to withdraw before his own avenue of escape was cut off. He heeded their warning, galloping ahead to Dublin with an escort of 200 men. The unbroken Jacobite left soon followed, retreating toward Duleek in good order. Casualties were relatively light for such a major battle. The Jacobites lost around 1,500 dead and wounded, the Williamites around 1,000. Some regiments, particularly those heavily engaged at Oldbridge village, were decimated, while others did not lose a single man.

The Pacification of Limerick

James arrived in Dublin and made his way to Dublin Castle to spend the night. Lady Tyrconnel met the deposed king and asked him what he would like for supper. James briefly filled her in on the battle, then added something to the effect that what he had received for breakfast—a catastrophic defeat—had left him with little appetite for supper.

When he went on to criticize the Irish troops, the doughty Lady Tryconnel gave him a piece of her mind. James complained that the Irish had run away from the battlefield, adding caustically, “Your countrymen, Madame, can run well!” Lady Tyrconnel replied, tongue firmly in cheek, “But not so well as Your Majesty, for I see you have won the race!”

Realizing that his cause was dead, James urged his followers not to continue the struggle, but to surrender and get the best terms they could. He urged that Dublin be spared pillaging and burning—he wanted no scorched-earth policy to mar his departure. He traveled to Waterford, then boarded a frigate at Kinsdale and sailed for France. William entered Dublin in triumph a few days later. Ignoring their departed leader, Irish Jacobites continued the fight, more for Irish nationalism than for the Stuart cause. Colonel Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan, reorganized Jacobite resistance and continued the struggle. Lucan, a strong and charismatic leader, managed to hold out for another year. In the meantime, William left Ireland, absorbed in his continuing campaign to curb the growing power of Louis XIV on the European continent.

The ensuing Pacification of Limerick, signed on October 13, 1691, was a just peace, guaranteeing the rights and property of Irish Catholics in return for a pledge of loyalty to William and Mary. Unfortunately, the liberal terms were altered by Irish Protestants, who enacted a rabidly anti-Catholic penal code. The Catholic gentry were dispossessed, stripped of all rights and rendered politically impotent. The mass of the Irish peasantry, poor and Catholic, sank into utter destitution, oppressed by high taxes and absentee British landlords. To the Catholic Irish, the defeat at the Boyne meant continuing exploitation and alien Protestant rule. Thousands fled their homeland and became soldiers in foreign armies, particularly in France. As the famed “Wild Geese,” these exiled Irishmen built a formidable reputation as soldiers in far-flung battlefields across Europe.

The Legendary “King Billy”

The Protestant Irish and Anglo-Irish of Ulster saw things quite differently. To them the Battle of the Boyne was their salvation, a miraculous liberation from a tyrant king and the false “popish” religion. Over the years Boyne legends grew, and the event entered the realm of mythology. The real William III of England, a hard-headed Dutch statesman and implacable enemy of Louis XIV’s France, became transformed into the legendary “King Billy,” champion of Protestant rights and bulwark against the perceived evils of the Catholic Church. William, who was a Protestant but also a tolerant man, would have been surprised at his mythic alter-ego.

The myth resonates to this day. In Northern Ireland, thousands of self-proclaimed Orangemen parade in orange sashes and full regalia, honoring the “glorious and immortal memory” of their beloved King Billy. Each July 12, under the new calendar, scores of painted banners and murals appear, all showing a heroic “Billy,” curled peruke and all, eternally crossing the Boyne on a noble white charger, his famous victory forever looming before him in the white smoke beneath a smudged blue sky.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments