by Adam Lynch

A few moments after his stricken Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber tore apart, co-pilot Ralph Patton hurriedly put his bail-out plan into action. ; [text_ad]

He had carefully thought it over many times since going into combat. Get out of the seat on the flight deck. Drop down into the well between the pilot and co-pilot seats onto the floor below. From there, reach under the seat for the chute, securing it to the harness with the correct clips and rings. He saw that at least the bombardier and navigator of the 10-man crew had already gone out.

Heavy flak over the target and vicious attacks by German fighters had combined to destroy the big ship. Their B-17, weakened and vibrating badly, had been unable to keep up with the group. Power had to be reduced, and as it slowly dropped behind, alone, German Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters came at it repeatedly. The uneven running battle ended dramatically when the entire tail section ripped away at 12,000 feet above the French countryside.

“I’m Going to Survive This War!”

Fortunately, the Flying Fortress, after briefly nosing up, stalled out straight and dropped into a flat spin before plunging down, giving Patton enough time to drop through the open nose. He learned later that the tail gunner, one waist gunner, and the ball turret gunner had been killed, but somehow seven men were able to bail out of the now uncontrollable and doomed bomber. Patton’s previous eight missions had taught him how quickly a B-17 could explode in flames and roll over, trapping the crew inside. He bailed out, quickly pulling the ripcord at about 10,000 feet, and years later described the opening of his chute as “the greatest sensation in the world.”

After a very long drop, he landed on French soil and repeated to himself, “I’m going to survive this war!”

The 23-year-old second lieutenant from Pittsburgh, Penn., had come down in the province of Brittany in the northwest section of France, not far from the English Channel. He knew the country was occupied by German forces and that his chances of avoiding a prisoner of war camp were slim, but he was determined to try.

Earlier that morning, January 5, 1943, his 94th Bomb Group of 23 B-17s had left their Bury St. Edmunds base in England and headed for the target, a Luftwaffe airfield at Merignac, just west of Bordeaux. Two bombers aborted, but 21 of the group’s Fortresses reached Merignac and were among the 112 B-17s that bombed the target that day. German defenses were formidable, and four B-17s of the 94th Bomber Group were lost among the 11 bombers shot down. Patton’s plane was first smashed hard with flak right after “bombs away.” The horizontal stabilizer was in shreds. For about a half-hour the crew fought for control, then the Focke Wulfs came in three separate, devastating attacks. For Patton and his crew, mission nine in the air ended when their plane broke apart. The fight to escape capture on the ground was about to begin.

The hedgerow Patton landed in was in the section of France where they spoke a Breton or Celtic tongue, but it mattered little since Patton spoke no French of any kind. Soon after the short co-pilot got out of his chute, Glenn Johnson his tall, 6’4” pilot, appeared. Johnson had bailed out right after Patton. Then, bombardier Jack McGough, who had also come down nearby, walked up. The trio stood in an open field, in enemy-occupied territory, trying to figure out what to do next.

After cautiously watching a nearby stone farmhouse for a half-hour, they approached the door and knocked. Despite the very serious risk involved, farmer Desire Gerone took them in, offering wine, hot soup and a welcome, roaring fireplace. It was the kind of bravery and compassion the men would see often in the months to come.

Unsure of what to do with the Americans, and unable to communicate, Gerone led them to yet another farmhouse some 200 yards away, owned by a Monsieur Denmat. Denmat did not know anyone to contact either, but he allowed the weary men to stay there for the night on welcome feather beds. After offering a breakfast of coffee and bread, Denmat produced a map, and the three Americans struck out in the vague hope of reaching Spain.

With no clear plan, walking mostly on the roads by night and hiding in fields by day, Patton, Johnson, and McGough pressed on. The second night the trio hollowed out a sleeping spot in a huge haystack, but the repeated barking by a farm dog revealed their presence. The dog’s owner arrived and peered in. “American … American,” said the flyers. The Frenchman smiled, departed, and then returned with a bottle of very strong, home- brewed apple schnapps.

“We Stayed Together and Got Away With It”

Unknown to Patton and his companions, waist gunner Isadore Viola and Norm King, the navigator from another B-17 crew that had bailed out, were not far away. The next day those two heard voices coming closer and dropped down into a ditch to hide. Suddenly, they realized who was approaching. With a cry, Viola leaped up and threw his arms around Patton, exclaiming, “I thought you were dead!”

The five men knew that the rules of evasion dictated not bunching up, but Patton says, “We didn’t have the heart or the courage to be alone. We stayed together and got away with it.” At one point, a French gendarme who saw them shook his head in disbelief, but ignored them.

Another Frenchman who spotted them standing dangerously out in the open near the town of Plouray uttered the French version of, “You gotta be out of your mind!” and hustled them into the basement of a nearby bistro where huge wine barrels filled the room. The five were fed cabbage soup and sardines and drank copious amounts of wine. After a few hours, Patton said their fatigue and fears melted away in a haze.

Upon leaving the bistro, they were taken into a nearby field to hide. They did not know it, but they had been spotted earlier by a fascinated 12-year-old schoolboy named Lucien Quillo. It was a vital sighting. The disorganized wandering by the five Americans was about to become planned and orchestrated. The youth knew instantly that he had seen American flyers, and he hurried to tell his teacher, an attractive and sophisticated 31 year old woman named Marie Antoinette Piriou. Mademoiselle Piriou was a small but important spoke in the escape and evasion wheel known as “Shelbourne,” and she knew how to get that wheel turning.

The Shelbourne freedom line hid and moved Allied flyers through France to the English Channel, where they could be met by fast British gunboats. Shelbourne, along with the “Pat” line, working in France and Spain, and the “Comet” line, primarily in Belgium, helped close to 3,000 American airmen evade capture and eventually return to England during the war.

In 1944, Shelbourne alone accounted for 135 agents and airmen of that total, sent out in eight separate missions. The complex and daring system was created by MI-9, the escape and evasion section of British Military Intelligence, which worked closely with its American Military Intelligence Section counterpart, MIS-X. It was a system born of necessity, for by the beginning of 1944, the air war waged by the British Royal Air Force and the American Eighth Air Force had grown into a massive effort.

Brave Citizens Hid the Men From the Germans

Thousands of Allied aircraft were now regularly committed night and day to smashing Nazi industrial and military strength. As a result, the number of British and American flyers who bailed out successfully over German-occupied European countries was growing.The brave citizens on the ground who wanted to hide these men from the Germans could not do it alone, so this behind-the-lines network was launched.

Highly trained, skilled Allied agents who dropped into Europe to establish sophisticated escape and evasion routes depended on brave French, Belgian, and Dutch civilians to make it all work. Every day, those men and women risked execution or being thrown into concentration camps if they were caught. An unknown number of selfless, dedicated patriots paid that supreme sacrifice.

The German military worked day and night to discover, infiltrate, and destroy the freedom lines and the people who operated them. German soldiers who spoke English were dressed in American Eighth Air Force uniforms taken from dead airmen and sent into the countryside posing as bailed-out American flyers. They would then ask for help, hoping to be taken in by the escape and evasion network. If successful, they moved along the line collecting names of those involved in the operation.Punishment was quick, and at least part of the line would disappear.

Warnings threatening execution to those who protected Allied flyers were posted everywhere. In France, 10,000 francs were offered to anyone who revealed the names of men and women who sheltered an American flier. Unfortunately, a few did just that. On the other hand, the “helpers,” as they were called, had only the satisfaction of knowing they were playing a role in finally driving the hated Boche from their land. Patton’s little band of bewildered Americans was about to be adopted into the Shelbourne evasion network, but it would not be fast, nor would it be easy.

Marie Antoinette Piriou, better known as “Toni,” had a “Parisienne” style with a commanding presence and she spoke English. Some in the village of Plouray thought she was a bit haughty, but when Toni spoke, people listened. Now, up the hill and into the field where Patton’s group was hiding, striding purposefully, came this woman of France dedicated to defending freedom. Toni had quickly turned her class over to another teacher the moment she heard from young Lucienne about the nearby Americans.

When she and her friend Josephine arrived, surprisingly, their first question was, “Do any of you know Frank Greene?” Greene, a ball turret gunner with the 303rd Bomb Group, had been shot down a year earlier and had been aided by these women in his successful return to England. Incredibly, bombardier Jack McGough did know Greene. It was a one in a million coincidence. After a few moments, Toni spoke quietly and with purpose, “You men stay here. We’ll be back tonight!” At last someone who knew what she was doing was taking charge.

A Very High Risk of Being Discovered

That night, Toni returned with Josephine’s fiancé, Marcel Pasco, and four other men. They, and the Americans began walking the two miles back to her schoolhouse, but by now waist gunner Isadore Viola had developed terrible blisters on his feet. He had lost his boots when bailing out, and a French priest had given him a pair of shoes that were too small, so walking had become terribly painful. The Frenchmen literally carried him all the way back to the schoolhouse.

The Americans spent the next five weeks hiding there while the Shelbourne high command planned its next move. A large number of citizens knew they were there, but no one talked. However, despite the presence of German troops throughout the area, the Americans and their helpers were becoming careless. At one point, Patton actually accompanied Toni into town just so he could see a German soldier.

Incredibly, one night they all went off to a party at the mayor’s house, singing as they walked through town. The Americans, who were by now dressed as French civilians, knew no French but they faked the lyrics and were in high spirits. For these Eighth Air Force flyers, the war had indeed taken a curious, almost surreal turn. They were popular guests as families competed for the right to have an American stay at their house. Finally, the Shelbourne leaders decided things were getting too dangerous and ordered the men divided.

Patton and navigator Norm King were sent to a bistro about three miles from the schoolhouse, while the three others were scattered in various safe places. In two weeks, another move was ordered as the underground was calling the shots and accelerating the process.

Patton and King now found themselves hidden in the rear of an upper floor of the Hotel Tournebride near the town of Langonnet. By now the Gestapo was snooping. The town’s telephone operator was questioned, but the integrity of the evasion operation was not compromised. Neither reward nor fear of reprisal led to a break in the mantle of secrecy.

Patton says that for weeks they had been aware that someone was organizing their movements, but the Americans had no knowledge of the complexity and size of the escape and evasion network in Europe nor its connection to British Intelligence. Briefings in England had not included that kind of information, and discussion among the operators in Europe was carefully guarded.

Patton and King moved again to a remote spot to meet a nighttime contact on a country road. Patton remembers, “It was pitch black and the only way we could stay on the road was by hearing the sounds our shoes made on the hard surface.” That contact led them to the rural home of Louis and Baptiste LeNaour, a designated stop in the Shelbourne underground railroad, where, for the next four days, the two lived in the loft of the LeNaour home.

Go, Fast! Go, Fast!

The process of moving them toward the coast was speeding up as Isadore Viola and Glenn Johnson were now also brought to the LeNaour home. Then, a snag developed. One night, two Frenchmen burst into the LeNaour house shouting, “Allez, vite! Allez, vite!” (Go, fast! Go, fast!). A man named Lacren had come for the men with a truck, but when he appeared he was late and frustrated. As instructed, he had earlier picked up one American, bombardier McGough, who was already in the back of the truck. But Lacren had been driving around trying to find the remote LeNaour farm and the other four Americans and was running out of time. He was supposed to drive them all to the train station at Gourin that night, but the half-hour he lost upset the timetable and the train they were to meet had already pulled out.

So, in another of those bizarre moments of so many in the entire adventure, Lacren, who was the town barber, took the men to his home for the night and gave all the Americans a badly needed haircut. It had now been two months of hiding, watching, and moving. Patton and his group went with the flow, and they knew enough not to ask questions. Still, it was a tense and unsettling aspect of the war for which they were not really prepared.

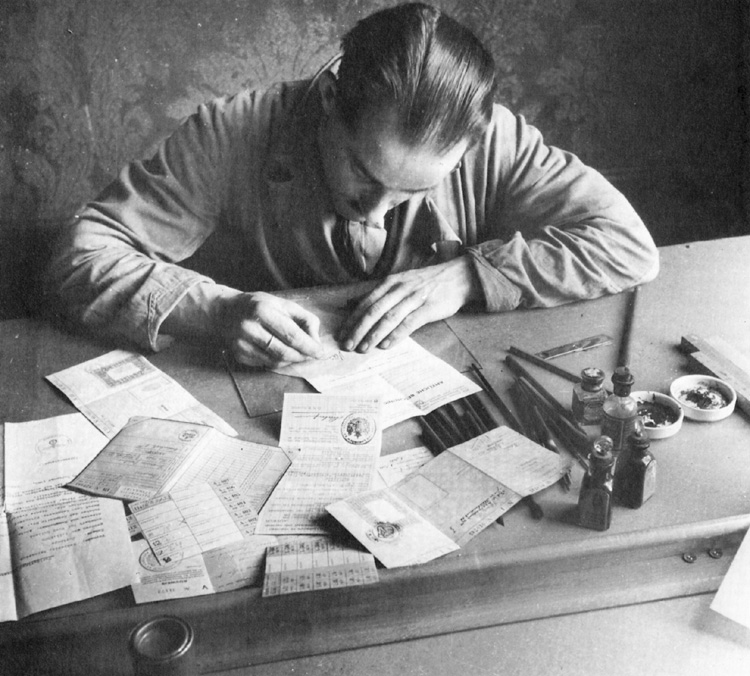

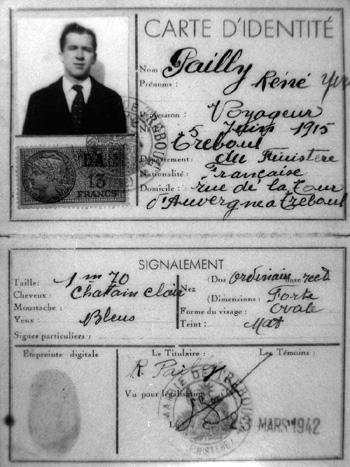

The next day, Lacren directed the five to the railroad station in Gourin where their orders were to look for a good-looking French youth carrying a rolled-up newspaper under his arm who would lead them to the correct train. The Shelbourne organizers had given the men French papers and identity cards bearing a picture taken in civilian clothes. Ralph Patton had become “René Pailly,” a mute identified as a “voyageur,” and the others had similar fake identification papers to go with their legitimate French outfits. There would be no singing or goofing off now. The adventure with the train would take their evasion skills to a new level.

The German Army was moving troops up to the northern coast of Brittany, and the first five cars of the six-car train were filled with Wehrmacht soldiers. Late in the afternoon, Patton and the others joined the unsuspecting French civilians in the last car. They avoided conversation, pretending to sleep and hoping they would not be challenged.

The train was agonizingly slow, stopping every few miles at stations along the way. Their destination of Guingamp was only 50 miles away, but the trip took four hours. At each stop, French men and women, who had been shopping for available food in the country, got on as German soldiers got out to stretch their legs. The tension-filled hours dragged by, but in the end the lengthy trip proved to be a blessing. German guards, who would normally have been inspecting passengers’ papers before anyone was allowed to pass out of the station, were now off duty. Patton and the others never had to produce their manufactured identity papers.

In Guingamp, they were split up again. Patton and McGough received yet another set of cloak-and-dagger instructions to follow a second man with a newspaper rolled up under his arm. The two were led to the Rue de l’Etang du Prieur and to the home of M. & Mme. Desire Laurent, the next stop in the Shelbourne freedom trail. During the war more than 30 men were hidden in that home even though the quarters for a German machine-gun company was just up the street and each day those soldiers would march past the house with their equipment.

Understandably, at those moments Patton would instinctively pull back from the window for fear of being seen, but Madame Laurant, with a smile, would say to him, “ It does not read, ‘I am an American’ on your forehead.” By now, Shelbourne was ready to make a big delivery. A large number of American flyers who had been moved along toward the coast were about to make their last rendezvous.

The “House of Alphonse”

The leader of the French Resistance group in the Guingamp area, Mathurin Branchoux, gave the go-ahead and on the second night at Rue de l’Etang du Prieur, Patton, McGough, and the Laurents had a visitor. François Kerambrun, owner of a garage in the town of Guingamp, delivered material for the Germans by day, in his large truck.

The Germans did not know that Kerambrun also ferried human cargo—American flyers—on some nights in a smaller truck. Kerambrun’s visit was not casual. He had been alerted to listen for a certain message broadcast on BBC radio that would be the signal to move another group of Americans to the coast. Patton and McGough were scheduled to be in that group. Conversation in the house was suspended as the announcer in England read a series of messages. Kerambrun listened intently.

Then it came—the coded phrase, “Bonjour, tout le monde a la maison D’Alphonse (Good day to everyone at the house of Alphonse).” To most, it would sound like an innocent greeting, but to those in the network it meant a British gunboat had departed Dartmouth on the southern English coast and was now headed across the Channel for the Brittany coast of France.

The “House of Alphonse” was in fact the home of Jean and Marie Gicquel. Located about two miles back from the beach on a high spot overlooking a cove on the coast. Kerambrun said quietly, “We go.” What the Shelbourne line called Operation Bonaparte was approaching its climax. If successful, escape from occupied Europe for another group of men of the Eighth Air Force was only hours away.

Kerambrun piled Patton and McGough into the back of his truck and, after making several stops at small villages along the way to pick up more evaders, headed for the little town of Plouha just east of the home of Jean and Marie Gicquel. By now, at least 10 men were jammed together. They stood most of the time, and the conversation was animated as the airmen asked each other, “What’s your name? … What group were you in? … When did you get shot down?”

Aware of the risk Kerambrun was taking if he were to be discovered, Patton asked their driver, “Aren’t you worried about transporting so many men in your truck at one time?” The reply was classic. “The penalty is the same for 10 as it is for one.”

On this night, March 18, 1944, the Gicquel home was filling up. Several Shelbourne helpers, 26 Americans, one French colonel, and a Canadian sergeant major in the British Army were there. The Canadian was Lucien Dumais, the commanding officer of Shelbourne. Dumais had been captured in the disastrous raid on Dieppe. He had escaped, returned to England, and was later parachuted back into France along with radio operator Sergeant Ray LaBrosse to help organize the Shelbourne line. It was Dumais, now going by the alias of “Captain Harrison,” who noticed something wrong.

Name, Rank, and Serial Number…

There were two too many men in the group. In a slip-up, Patton and McGough had been picked up one day early. Dumais asked, “How come we have 26 men not 24?”

Aware that the Germans constantly tried to infiltrate the escape lines, Dumais began asking pointed questions. From the back of the room, an impatient American flier called out, “You don’t have to give him anything but your name, rank, and serial number.”

Dumais took out his .45-caliber automatic and said in a commanding voice, “Shut up. I am Captain Harrison of the British Intelligence Service and these two [Patton and McGough] are going back to England with or without holes in their stomachs depending on what they tell me.”

The questions came quickly. “When do you wear epaulets? Do you wear anklets? What was your last stopping point when you left the USA?” Patton and McGough stumbled a bit in their answers, which may have helped convince “Harrison” they were not trained German plants, but in fact just two nervous and tired American airmen. The crisis passed as the “captain” quietly announced, “You are about to face the most difficult part of your journey. Do exactly as you are told!”

About midnight, the men were led from the house to a spot about two kilometers away, close to the top of a 200-foot cliff above the beach. This part of the French coast was studded with German gun emplacements, so the group was warned to stay on the narrow path and keep quiet as they moved along. Before starting down, they were told to dig their heels in to avoid falling in the darkness. Halfway down, Dumais directed the quick flashlight to signal the letter “B” out over the water to the waiting boat.

Was it really going to happen? Was this little band of evaders finally going to get out of occupied Europe and back to England? Well, not right away. After successfully reaching what the French called Bonaparte Beach, the group of evaders, agents, and Shelbourne helpers, now numbering 35 people altogether, sat on large rocks at the foot of the cliff in the cold and waited … and waited. With each passing wave the little band of flyers imagined they could see an approaching boat. Suddenly, the sky turned bright as day, followed a second later by the thundering roar of big guns. The German coastal batteries were firing into the night. Patton says, “ It scared the daylights out us.” The group feared the guns were shooting at the British gunboat now holding about a mile off shore, but apparently it was only practice firing.

Patton’s Worst Moment

Finally, an hour and a half after reaching the beach, as quiet and the black of night returned, five plywood rowboats appeared out of the dark. It was about 3 AM, and each boat was manned by a British seaman. After being turned away from several boats because they were full, Patton feared he was losing his chance to get away. He called it his worst moment. But moving quickly from one to another, he was finally able to find a boat that would take him in.

After the boats had gone, the French patriots began their slow climb back up the cliff to prepare for the next mission the following night. Almost three months had elapsed since Ralph Patton’s crew had bailed out of their broken B-17. Pilot Glenn Johnson, waist gunner Isadore Viola, and navigator Norm King would be included in the next night’s departure on March 19. Flight engineer Ralph Hall, who narrowly avoided capture during an earlier failed pickup at another location, did not manage to leave France until the area in which he was hiding was liberated.

Unknown to Patton and McGough, their radio operator, Ken Blye, and navigator, Milt Church, had gone out from Bonaparte Beach one month earlier. None of the six men who bailed out along with Patton ever became a prisoner of war. In July, the Germans, unsure of what was actually happening, but suspecting the “House of Alphonse” was being used for anti-war activities, burned the modest farm home of M. & Mme Gicquel.

After a short ride, the rowboats reached Motor Gunboat (MGB) 503, and the men were taken below. As if to remind the evaders that the war was still on, a report reached the gunboat that a group of German E-boats had been spotted between them and the English coast.

Patton says at no time during his adventure on the Continent was he ever truly frightened, but the news of the E-boats did trigger some serious concern. However, no contact was made as MGB 503 sped along at 30 knots. Patton says, “I truly felt now we were going to make it.” Early the next morning, the Americans watched gratefully as Dartmouth, England, slowly came into view. Interrogation and debriefing would follow as the men began to unwind from their unexpected European adventure. Tragically, MGB 503 hit a mine in the North Sea the day after VE-Day and all but two of the crew were lost.

As for Patton and the other fliers, their combat days were over. The high command believed it was too dangerous to risk having successful evaders shot down and captured in the future. By early 1945, as the American and British armies liberated one country after another, Allied flyers who had been hiding out were found, POW camps were opened up, and French, Belgian, and Dutch civilians celebrated. Those who had risked their lives in Shelbourne, Pat, and Comet again enjoyed the peace of their farms, schools, and shops. They remained relatively anonymous for years, and then, a few at a time, the Americans began to come back.

Men started seeking out their wartime benefactors, wanting to say thank you. Over the years, farmhouse meetings and formal reunions in both Europe and the United States have been filled with predictable emotion. Those who offered and lost their lives are toasted, incredible stories are told and retold, and the grateful members of the Escape and Evasion Society repeat their pledge to their now aging helpers: “We will never forget.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments