By Bernd Horn

In the hut no one spoke, no one joked. The assembled British and Canadian paratroop commanders awaited the briefing from their brigade commander on their next major operation. When it came, they were not disappointed. “Gentlemen,” bellowed Brig. Gen. James Hill, the well-respected commander of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, “the artillery support is fantastic! And if you are worried about the kind of reception you’ll get, just put yourself in the place of the enemy. What would you think,” he posited to the troops, “if you saw a horde of ferocious, bloodthirsty paratroopers, bristling with weapons, cascading down upon you from the skies?”

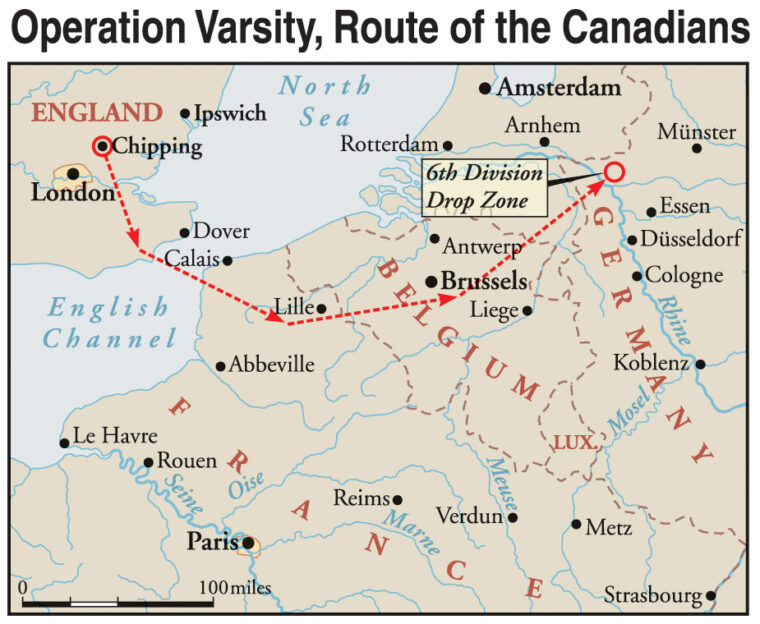

The image set all at ease. Among those assembled for the briefing on Operation Varsity, the airborne assault that would breach the Rhine into the heart of the Reich, was a small group of Canadians who belonged to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

The Canadian unit itself was a dark horse. During the early years of the war, Canadian commanders and politicians dismissed the idea of airborne forces as a luxury the Canadian Army could not afford, and for which it had no use. But the continuing American and British development of these forces and subsequent belief that paratroopers were a defining element of a modern army led the Canadians in July 1942 to organize paratrooper units, though on a much smaller scale than their American and British counterparts. Unsure of what to do with their paratrooper commands, the Canadian government attached them to the British 6th Airborne Division in the summer of 1943. The 6th subsequently distinguished itself during the Normandy invasion and breakout campaign in June-August 1944. They quickly demonstrated themselves to be preeminent combat troops.

The battalion had just returned to England from its emergency deployment to the Ardennes where it assisted stemming the surprise German Christmas offensive. The Canadian paratroopers now prepared for their next mission where they would once again be thrust into the forefront of battle.

Hitler’s failed gamble in the Ardennes in December 1944 exhausted what little reserves the Germans had been able to cobble together. Conversely, the Allies had, by mid-January 1945, not only beaten off the desperate German counterattack but also, despite the heavy losses sustained in the Battle of the Bulge, amassed almost four million men under arms in northwest Europe. Consequently, the Allied steamroller once again began its relentless advance. By March 10, 1945, the Germans were forced to withdraw to the east bank of the Rhine River in a last effort to defend the German frontier itself.

Planning for the crossing of the Rhine River had begun as early as October 1944. At this time, Allied brass targeted the Emmerich-Wesel area as a crossing point because of its strategic location close to the vital industrial Ruhr region, as well as the suitability of its terrain for a rapid breakout by mechanized forces once a bridgehead was gained. In addition, the ground lent itself to the possibility of large airborne operations in support of the complex river crossing. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and his 21st Army Group were charged with conducting the portentous assault into Germany, which was given the code-name Operation Plunder.

Lt. General Dempsey was Given the Task of Seizing Wesel

“My intention,” recalled Montgomery, “was to secure a bridgehead prior to developing operations to isolate the Ruhr and to thrust into the Northern plains of Germany.” He planned to cross the Rhine on a front of two armies between Rheinberg and Rees with the Ninth U.S. Army on the right and the Second British Army on the left. He wanted the bridgehead to be sufficiently large to cover Wesel in the south from enemy and ground action, and to encompass bridge sites to the north in Emmerich. Equally important, the bridgehead had to provide enough space to form up large formations for the drive that would culminate in the complete collapse of German resistance.

Montgomery assigned to Lt. Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey’s Second Army the task of thrusting across the Rhine and seizing Wesel. To assist Dempsey, Montgomery was given use of the First Allied Airborne Army (FAAA), which was responsible for dropping the American XVIII Airborne Corps in support of the operation. The XVIII Airborne Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, consisted of the U.S. 17th and British 6th Airborne Divisions. Its mission was to “disrupt the hostile defense of the Rhine in the Wesel Sector by the seizure of key terrain by airborne attack, in order to rapidly deepen the bridgehead to be seized in an assault crossing of the Rhine by British ground forces.” The airborne component of the assault into Germany was designated Operation Varsity.

The final XVIII Airborne Corps plan centered on dropping the two divisions abreast. They were to seize the Diersfordter Wald and high ground three to five miles east of the Rhine and north of Wesel up to the Issel River. Allied commanders felt this was critical to the success of the assault river crossing because it would bottle up potential reinforcements, and more significantly, deny enemy artillery observers the ability to call down accurate and devastating fire from the ridge that dominated the Rhine. Equally important was the necessity to seize control of the five-by-six mile tract of woods covering the high ground that could mask camouflaged, well-entrenched enemy infantry and gun positions. These were thought capable of inflicting punishing casualties and significant delay to the crossing and subsequent breakout operations.

As a result, the 17th U.S. Airborne Division was ordered to seize, clear, and secure the high ground east of Diersfordt plus a number of bridges over the Issel River to protect the southern flank of the airborne corps and to establish contact with 1st Commando Brigade in Wesel to its right, 6th British Airborne Division to its left, and 12th British Corps to its rear. The 6th British Airborne Division was ordered to seize the high ground east of Bergen in the northwest part of the Diersfordter Wald, the town of Hamminkeln, and a number of bridges over the Issel River. It was also responsible for protecting the northern flank of the airborne corps and for establishing contact with both the 12th British Corps moving up from its rear and the 17th U.S. Airborne Division on its right.

In turn, the mission assigned to 3rd Parachute Brigade, to which the Canadian paratroopers belonged, was to secure the drop zone and then clear the northern part of the Diersfordter Wald. More important, it was given the daunting mission of seizing the 150-foot-high Schnappenburg feature that was defended by the well-bloodied 7th German Parachute Division. The brigade had to silence all enemy artillery positions and infantry entrenchments in the woods and surrounding farms and villages.

The brigade’s 8th Battalion was ordered to seize the northern part of its allocated section of the Wald, while the 9th Battalion was assigned responsibility for the southern part, including the Schnappenburg feature. The Canadian paratroopers were responsible for the central part, specifically the western part of the woods, a number of buildings, and a section of the main road that ran north from Wesel to Emmerich.

Overwhelming force available to smother German resistance was not the only component of the plan. Airborne operations had markedly matured since the beginning of the war, and commanders considered some dramatic departures from established practice. Most significant was the decision to drop the airborne troops after the actual crossing of the Rhine River by ground forces. FAAA commanders and planners quickly noted that an airborne operation before the crossing would “hamstring artillery for the assault crossing.” Moreover, they argued that the river crossing was not the most difficult part of the operation, but rather the real challenge lay in “the subsequent expansion of the bridgehead and in particular the capture of the Diersfordter wood” to ensure that the assaulting division would not be hemmed in on the far bank.

The Allied Troops Planned a Risky Daytime Paratroop Assault

Montgomery endorsed this plan. Both he and his airborne commanders were convinced that a daylight drop would avoid problems experienced in previous airborne operations, such as missing drop zones, scattering of troops, assembling paratroopers in a timely fashion once on the ground, navigating to the objective, and providing troops with adequate protective fire. In addition, both divisions were to be dropped directly on their objectives within range of their supporting guns on the west side of the river. This available fire support would not only provide immediate assistance to the paratroopers but it would also facilitate linkup with ground forces on the first day, thus overcoming two fundamental problems experienced on earlier airborne missions.

The hazards of a daytime drop, however, particularly into an area that was easily recognized by the enemy as ideal for an airborne assault and known by the Allies to be inundated with flak positions and machine-gun nests, was well understood by airborne commanders. Nonetheless, they felt that the risk of a daylight drop directly on the objective would be mitigated by concurrent actions of the ground force, as well as the preparation of the battlefield by the Allied Air Force. They believed that by conducting the river crossing first, the German commanders would react accordingly and be preoccupied with the hordes of Allied forces flowing across the Rhine.

“Well, gentlemen, you’ll be glad to know,” announced Maj. Gen. Eric Bols, commander, 6th Airborne Division, “that this time we’re not going to be dropped down as a carrot held out for the ground forces.” He explained that the “Army and the Navy are going to storm across the Rhine, and just when they’ve gained Jerry’s attention in front—bingo! we drop down behind him.”

The airborne commanders also placed faith in the bombing campaign which, compounded by artillery support from the friendly bank, would theoretically disorient and destroy German infantry, artillery, and antiaircraft positions. They also felt that by landing directly on their targets, the paratroopers would avoid a long, drawn-out fight to their objectives and be able to simply overwhelm any enemy force that survived the aerial and artillery bombardment.

To that end, it was decided that the airborne force be “put down in the shortest possible time” into a concentrated area. In addition, the glider element of the parachute brigades was increased above the normal allocation to enable the carriage of heavy weapons, jeeps, stores, and reserve ammunition. This also allowed for a margin of safety should attrition en route to and on the objective be excessively high. Finally, of equal importance, as already noted, landing on the objective enabled the airborne force the ability to link up with ground forces on the first day, alleviating the lightly armed paratroopers from a lengthy defense such as that experienced at Arnhem, in Holland, six months earlier.

The overall plan was carefully knit together and the necessary coordination completed. On March 14 a firm decision was made to conduct both Operation Plunder and Operation Varsity on March 24. Despite the overwhelming force that was amassed to crush German resistance, further steps were taken to guarantee success. During the three days before the operation the Allies waged a massive bombing campaign designed to suppress German preparations, communications, and capacity to fight.

The Germans Suffered Massive Damage Before Allied Soldiers Even Crossed the River

In the initial phase, Allied bombers flew over 16,000 sorties and dropped nearly 50,000 tons of bombs. These strikes not only hampered the movement of vital economic traffic from the Ruhr industrial region, but also denied the enemy the ability to communicate and move large-scale reinforcements of men and materiel to the targeted Rhine area. In addition, 14 bridges and viaducts were made impassable, enemy headquarters complexes and hutted camps were demolished, 160 enemy aircraft were destroyed, and 23 known flak positions in the area of the parachute dropping zones (DZ) and glider landing zones (LZ) were neutralized. All told, the Germans suffered colossal damage before the first Allied soldier crossed the river.

Although initial planning for Operation Varsity had begun in October 1944, ongoing operations and the crisis in the Ardennes pushed the planning process to the back burner. When it was resurrected in February and March 1945, there was little time to mount the large preparations attendant to the Normandy invasion. On the other hand, there was neither the same interest, nor the same sense of significance—everyone was tired of the war. Moreover, it was apparent that the German Army was rapidly crumbling. “There was also some feeling,” acknowledged veteran paratrooper Sergeant Andy Anderson, “that the success of the mission perhaps did in fact mean a rapid end to the war.”

And so, when the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion returned on March 7 from seven days of leave awarded after its return from the Ardennes campaign, there was little time for much worry or preparation. The battalion was brought up to full strength. All personnel were once again tested on their weapon drills and then conducted field-firing exercises and a review of battle drill. But the need to pre-position and prepare equipment, as well as the necessity of not injuring soldiers before the operation, meant that no large-scale exercise or practice parachute drops were made.

This state of affairs did not sit well with the Canadian paratroop commanders. Their men had not jumped since November 1944. And now, they were expected to jump onto the objective, into waiting enemy guns, without the ability to rehearse their parachuting drills.

Nevertheless, anxiety was put aside so that all could get on with the realities of a complex operation. On March 19 follow-on equipment in the form of large packs was submitted

for transit overseas.

The next day the battalion was confined to Hill Hall Transit Camp in East Anglia in England. For the next three days the paratroopers were briefed on plasticine models and enlarged maps. Weapons were repeatedly cleaned and checked. Personal equipment was nervously prepared and in many cases, final letters written for loved ones back home. The waiting was always the worst. Nonetheless, the battalion was set. “If ever a fighting unit was ready for anything,” extolled one veteran paratrooper, “this had to be it.”

On March 23 the guns suddenly lifted their bombardment. Under cover of darkness British Commandos commenced their attack on Wesel. An hour later, the Second British and Ninth U.S. Armies began a series of assaults across the Rhine that were to continue throughout the night. By first light, they had secured nine small bridgeheads between Emmerich and Wesel.

As the Allied ground troops swarmed across the Rhine in the eerie darkness, the airborne forces were just beginning to form up in bases in England and France. The aerial armada, numbering 1,696 troop transports and 1,050 tug aircraft towing 1,348 gliders departing from 26 airfields, headed for the crowded airspace over Belgium. In their cramped fuselages were crammed approximately 14,000 American and British airborne soldiers. In support were 889 escorting fighters to ensure the air fleet was not molested by German fighter aircraft. In addition, another 2,153 fighter aircraft maintained an umbrella over the target area or ranged far over Germany hunting for any enemy plane that would dare to take off.

For their part, the Canadians had wakened at two in the morning and enplaned aboard 35 C-47 Dakota aircraft. By 7:30 am they had departed from Chipping Ongar airfield in Essex for their two-hour flight to Germany. The aircraft were crewed by airmen of the American IX Troop Carrier Command.

“They were the scruffiest looking guys, with baseball hats and cigars,” recalled Major Richard Hilborn, “but they were awfully good.” Another veteran said, “The Yanks radiated matter-of-fact confidence, well suited to the fleeting but vital relationship between parachutists and aircrews.” In fact, their skill was one of the primary reasons that Brigadier Hill based his plan on dropping 2,200 fighting men into a comparatively restricted area that measured approximately 800 by 1,000 yards in six minutes.

“Whole Towns and Villages Burning in an Utter Holocaust.”

The flight across the English Channel and France was uneventful. The weather was perfect—a clear, blue sky and negligible winds. “It was a gorgeous morning,” recalled Dan Hartigan, “one of the most beautiful days I’ve ever experienced.” Joe King agreed. “Going across the Channel,” he said, “seeing all those aircraft in the beautiful morning sky was fantastic.” Moreover, not a single German aircraft penetrated the Allied fighter shield. “We met no opposition until we were right over the dropping zone,” boasted one airborne commander. “The air cover was wonderful.”

The tranquility, however, was deceiving. On the ground was a different story. “Pilots who flew east of the Rhine and north of the Ruhr,” reported one journalist, “had never seen anything like it—whole towns and villages burning in an utter holocaust.” The Canadian paratroopers would soon find themselves dropping into this furnace.

“Looking out the window briefly before ‘Stand Up’ my impression is of a very wide lake,” wrote Sergeant Anderson. “I have no idea what I expected, but the river was massive, cold and uninviting … within seconds someone hollered the customary, ‘stand up and hook up.’”

But Anderson’s attention, as with so many others, was soon focused on the battle for survival. The transport planes, flying in nines, held true to their course and maintained a steady formation despite the heavy flak that now spit up from the ground. “We went out in a tight formation,” confirmed Private Jan de Vries, “the pilots took no evasive action.”

Private Morris Zakaluk recalled that “it was a ride to enjoy.” But as they neared their objective, “I could see puffs of smoke in the air between hundreds of planes,” he recalled, “anti-aircraft shells exploding and tracers arcing their way into the sky,” mixed with “balls of fire”—aircraft hit and cascading to earth.

“Lying on the ground, looking up taking off my chute,” remembered Lieutenant William Jenkins, “I could see these things [C-47s] blasted all over the sky.” He added, “I couldn’t help but admire those guys.” The deputy commanding officer during the jump, Major Fraser Eadie, noted, “They came in a little higher than we wanted—we wanted 450 feet.” Nonetheless, “the Yank aircraft did a hell of a job for us. I have never been on a better drop, not training or operational.”

Major Hilborn wrote that his “pilot put us down approximately 100 yards from where I wanted to be within a minute of the time I had to be there.”

The descent was not quite as accommodating. Neither the aerial bombing nor the artillery bombardment was as effective as the airborne soldiers had been praying for. Zakaluk was relieved to feel his parachute open and find himself descending to earth. But his relief soon dissipated. “Buzzing all around me!” he recalled, “I can’t see them, but I can hear them.” Then it dawned on him: “Hey! These guys are shooting at me!”

He was not the only one. “I heard bullets going by and looked up to see bullet holes in my chute,” remembered Private de Vries, “it sounds just like being in the rifle butts!” His thoughts, he admitted, “were to get down fast.” Major Eadie too became the target of some well-aimed shots that cracked about his ears. He quickly went limp in his harness, feigning death in hopes this would fool the Germans. It seemed to work, although his landing left a lot to be desired.

On the ground the airborne forces met with varying resistance. In some areas opposition was negligible, but elsewhere troops dropped directly on entrenched enemy positions, including dug-in artillery and air defense guns. From Eadie’s vantage point, “It was hot!”

One paratrooper recalled that he landed “like a rock,” and found himself stretched out on the ground, somewhat amazed to find nothing broken, and his kit bag still intact. Like others, he unpacked his gear and started for the rendezvous point (RV) at the edge of the woods about 200 yards away. “Crouched low, running like hell,” he recalled, “[I was] conscious of fire coming from somewhere, and several men lying motionless on the DZ.” A paratroop officer later acknowledged, “It was real flat-out fighting until about noon.” Another simply said it was “two hours of real killing.”

German Soldiers Fought Back “Like Tigers”

James Hill, the commander of 3rd Parachute Brigade, had counseled his NCOs before the operation that “if by chance you should happen to meet one of these Huns in person, you will treat him, gentlemen, with extreme disfavour.” But evidently the enemy was given the same type of briefing. Although the Third Reich was crumbling, its soldiers were still proving to be formidable foes.

The Germans we were up against on this operation put up a pretty good fight,” said Company Sergeant-Major (CSM) Johnny Kemp, “they were as good as us.” Even the 6th Airborne Division intelligence staff had to begrudgingly agree. Although they reported that the German First Parachute Army was severely mauled in the preceding month on the west side of the Rhine, the “Estimate of the Enemy Situation” before Operation Varsity warned that the enemy’s fanaticism and level of skill was still such that they would be able to provide fearsome opposition.

And they did. Every farm was turned into a stronghold. “Morale was fairly high and this was especially true in the Fallschirm divisions,” said Lt. Gen. Gustav Hoehne, commander of the German 2nd Parachute Division in a postwar interrogation. But many of the Canadian paratroopers already knew this—the contested areas of the drop zone were murderous. “They were young and full of fight,” reminisced Dick Creelman. Another paratrooper remembered that “they fought like tigers.”

German tenacity did not bode well for the paratroopers. As the first Allied parachute formations appeared over the target at 9:52, an unexplained eight minutes early, enemy reaction began slowly but quickly gained momentum. The Canadians jumped three minutes later. Dug in on the edge of the woods, the German machine guns and light flak cannons now wreaked havoc on the DZ. It was chaos. “We were getting pretty badly hammered from some houses on the edge of the field we landed in,” recollected CSM Kemp. “We knew we had to attack them right away.” Most of the battalion faced heavy machine-gun and sniper fire, which accounted for most of the unit’s casualties.

“We were fighting right on the dropping zone immediately as we landed,” said Lieutenant Bob Firlotte. “It was pretty bad.”

Quigley Inspired the Soldiers to Follow Him into a Hail of Bullets

But this was not totally unexpected. “Listen clear now! Pay attention!” senior NCOs had bellowed in the different aircraft. “As soon as you hit the bloody deck, and you’re out of your parachutes, fix bayonets and go for the goddamn woods!” Most followed this advice. The DZ became a hive of activity with small groups of men shedding their parachute harnesses and rushing the wood line, firing from the hip. Officers and NCOs attempted to rally men to form organized assaults wherever possible. Where they were lacking, privates took the initiative. Private James Quigley gathered a number of men who were milling around him on the DZ, but were uncertain of the direction to the rendezvous point. Despite the intense fire, “by his dash and contempt for the hail of bullets he inspired them to follow him” and destroy a company objective.

The battalion quickly gained the upper hand despite the variance in the quality of the enemy and the subsequent level of resistance encountered. “It was individual fighting in the first stages until we got organized,” recalled Hilborn, “and the boys did a terrific job.” Then, organized, there was no stopping them. “C” Company, just as in Normandy, was once again the first Canadian subunit to jump. They raced off the DZ to their RV points from where platoons quickly assaulted their objectives—a series of road junctions, wood lines, and the Hingendahlshof farm. Within 30 minutes they had achieved all of their tasks.

This they accomplished without their senior leadership. The company commander, Major John Hanson, broke his shoulder on landing. The second-in-command, Captain John Clancy, and a platoon commander, Lieutenant Ken Spicer, failed to reach the DZ—their plane was hit by flak on the approach and set ablaze. Fortunately for them, the aircrew struggled to keep the airplane aloft and the paratroopers managed to bail out. All were dispersed, however, and Clancy was captured. Nonetheless, Sergeants Miles Saunders and Bill Murray quickly organized the available troops and accomplished the company’s mission. With their objectives secure, they then dug in on the north side of the battalion perimeter. But for them the pressure remained. For the next 16 hours they held off German probing attacks and exchanged direct and indirect fire with an enemy that would not quit.

Concurrently, “A” Company landed on the eastern end of the DZ. They had an accurate drop, and within 30 minutes were organized in their RV with approximately 70 percent of their men. The officer commanding, Major Peter Griffin, decided to mount an immediate attack on a group of buildings that were designated for use by battalion headquarters. Initially they met fierce enemy resistance, and the attack seemed to falter. Without hesitation, and under heavy fire, CSM George Green organized covering fire and then led a PIAT antitank weapon detachment up to the first house. Using the weight of fire to his benefit, he then personally led the assault into the building. After vicious close-quarter combat, the structure was rid of Germans. Green then went on to clear the remainder of the houses in a similar manner. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his “contempt of danger” and “inspiration to the men.”

The unit reported its objective clear by 11:30 and subsequently took up a position at the southern end of the village of Bergerfürth. Later in the day the Germans attempted to recapture the lost territory, but “A” Company held them back.

“B” Company’s reception, much like that of “C” Company, was heavily contested. The company second-in-command described the DZ as a “holocaust. Everyone running in all directions, but finally following NCOs and officers to the RV.” The company formed up in the rendezvous point “with the usual confusion that is attached to a reorganization.” The commanding officer, Captain Sam McGowan, showed up late, bleeding heavily and sporting a bullet hole in his helmet that miraculously entered the front, traveled around the inside rim and then exited through the back. He immediately directed the platoons to assault their objectives.

These were a group of farm buildings and a wooded area. Under a heavy covering fire from their Bren guns, “B” Company quickly “overran the bunkers and buildings, driving the Germans out with grenades and gunfire.” The Bren-gun coverage kept the enemy’s heads down, explained one veteran, who added, “We ran in right after the explosion and shot up anyone still there.” It was controlled chaos. “We are off and running,” wrote Sergeant Anderson in his diary, “firing wildly from the hip covered by Bren fire. We overrun bunkers, toss grenades into the houses and barns, generally raise hell and take a few prisoners.” In less than 30 minutes they too had secured their objectives.

Having established “B” Company in a defensive position to his satisfaction, the company commander ordered a patrol under the command of Sergeant A. Page to clear the woods in the vicinity of its perimeter. Soon Page and his six-man patrol returned with 98 prisoners. Throughout the day the company engaged enemy soldiers attempting to flee the battle.

By noon, the battalion was firmly in control of its area of responsibility. In fact, this was the case for the entire formation. Within 35 minutes of the drop, 85 percent of the brigade had reported in, and objectives began to fall. Throughout the day, as the battalion settled into its defensive position, stragglers—many wounded—continued to report in to their respective organizations. By 2 o’clock in the afternoon it seemed as though direct enemy resistance in the immediate area had ceased. Consequently, patrols were dispatched to ensure the DZ and surrounding woods were clear of enemy. In addition, the patrols searched for missing, wounded, or injured paratroopers. They also attempted to bring in much needed supplies from the damaged gliders that lay strewn around the landing zone.

109 Tons of Ammunition, 695 Vehicles, and 113 Artillery Pieces had been Landed by Gliders

Throughout the night the Germans made attempts to infiltrate the position or simply to escape the Rhine bridgehead. The alert paratroopers, with the aid of their Vickers medium machine guns (MMG) and mortars, ably responded to the enemy movements. However, at first light a number of self-propelled (SP) guns began to fire at the battalion positions from 400 yards. The SP guns specifically targeted the Vickers MMGs and mortars owing to their effectiveness. German infantry then began an assault but quickly withdrew as a result of the withering fire that poured into their ranks. One SP gun was destroyed and another pulled back when four PIAT antitank weapons and mortars fired on them. The defeat of the latest attack marked the end of the Germans’ counter moves. Although the enemy had now largely disappeared, they still maintained harassing mortar and artillery fire—but these became more of a nuisance than an actual threat.

The battle was brief but exceptionally bloody. Two-and-a-half hours after the airborne assault, all Allied paratroops had been dropped and were in possession of their designated objectives. Moreover, 109 tons of ammunition, 695 vehicles, and 113 artillery pieces had been landed by gliders. The cost was high, however. Within the 6th Airborne Division approximately 45 percent of the vehicles, 29 percent of the 75mm Pack Howitzers, 50 percent of the 25-pounder artillery pieces, and 56 percent of the 17-pounder antitank guns delivered by gliders were damaged or destroyed. The casualty count for the division was 1,297 killed, wounded, or missing.

The battalion lost 67 of approximately 475 soldiers, including its commanding officer, Lt. Col. Jeff Nicklin. When he failed to show up at the RV, Fraser Eadie immediately took command. However, as time went on, concern began to mount. A clearance patrol found Nicklin approximately 36 hours after the attack. He was hanging from a tree still in his parachute, his body riddled with bullets. He had dropped into the trees directly above German entrenchments and never had a chance. The news was a shock to many. He was “one who almost seemed indestructible,” remarked Anderson, “6’3’’ tall, football hero back home, a stern disciplinarian, physical fitness his specialty.”

Ironically, Nicklin normally jumped in the middle of the stick so that he could have half of his headquarters on either side of him upon landing. But for this operation he wanted to be the first jumper so that he could lead his troops into battle. That decision cost him his life and the battalion their commanding officer.

As the members of the battalion reflected on their accomplishments, as well as their lost comrades, a fatigue and quiet personal rejoicing seeped over them. Harrowing tales of close calls and stories of individual gallantry and heroism now surfaced. One such account revolved around Corporal Frederick Topham, who earned the only Victoria Cross to be awarded in the 6th Airborne Division during World War II. The 27-year-old Toronto native was the 11th Canadian to win the British Empire’s highest award for bravery in the war.

During the initial battle, while treating casualties on the drop zone, Corporal Topham and several other medical orderlies heard a cry for help emanating from the fire-swept DZ. Two medics moved forward to rescue the wounded soldier. But they were themselves perfunctorily shot and killed. On his own initiative and without hesitation Topham braved the intense fire to assist the wounded paratrooper, even though he saw the other two orderlies killed before his eyes. “I only did,” he later modestly stated, “what every last man in my outfit would do.” As he treated the wounded soldier he was shot through the nose. Bleeding profusely and in great pain he completed first aid and then carried the wounded man slowly and steadily through the hail of fire to protective cover in the woods.

For the next two hours Topham refused medical attention for his own wound, and continued to evacuate casualties from the drop zone with complete disregard for the heavy and accurate enemy fire. “I didn’t have time to think about it,” he later explained. “I was too busy.” It was not until all the wounded paratroopers had been evacuated that he allowed his wound to be treated. By now his face had swollen up enormously and the medical officer ordered his evacuation. He interceded with such vigor that he was allowed to return to duty. On his way back to his company, he came across a Bren-gun carrier that had just received a direct hit. It lay burning fiercely, amid falling enemy artillery shells and its own exploding mortar ammunition. Despite the direction of an experienced officer on the spot who warned everyone not to approach the carrier, Topham immediately went out alone, rescued the three occupants, and arranged for their evacuation. Topham’s valor was unrivaled. “For six hours,” read his commendation, “most of the time in great pain, he performed a series of acts of outstanding bravery, and his magnificent and selfless courage inspired all those who witnessed it.”

“The Very Concentrated Drop Gave an Impression of Irresistible Might.”

Bravery and courage by all belligerents aside, it became clear early on that the airborne assault had been a success. “The sight of the massive drop,” wrote one Canadian veteran, “descending in an area about ten by ten kilometers square, floored the enemy.” The show of force could not but impress even the Allied soldiers. “The very concentrated drop,” wrote a medic, “gave an impression of irresistible might.”

A British infantry captain, voicing the opinion of many, questioned, “How on earth can they go on in face of this?” Indeed, German prisoners attested to the hopelessness they felt once they witnessed the overwhelming number of paratroopers who seemed to flow from an endless stream of aircraft. Major-General Fiebig, commander of the German 84th Infantry Division, confessed he “had been badly surprised by the sudden advent of two complete divisions in his area,” and throughout his interrogation reiterated “the shattering effect of such immensely superior forces on [his] already badly depleted troops.”

The effect on the enemy quickly translated itself to events on the ground. By 3 o’clock in the afternoon reconnaissance elements of the 15th Scottish Division linked up with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. By 4:30 in the morning the first armored columns of tanks and Bren-gun carriers of the 15th Scottish Division began to pass through the unit’s position. The paratroopers welcomed them warmly. They had achieved linkup with the ground force in less than 24 hours. But there was little time to celebrate. The final push was now commencing.

The following day, March 26, almost 48 hours after the battalion’s drop into Germany, the Canadians were ordered into a brigade assembly area for a hot meal and some rest. “The battalion,” boasted Hill, “really put up a most tremendous performance on D-day and as a result of their dash and enthusiasm they overcame their objectives, which were very sticky ones, with considerable ease, killing a very large number of Germans and capturing many others.”

Overall, Allied commanders declared that Operation Varsity was an enormous success. “The airborne drop in depth,” explained Maj. Gen. Ridgway, “destroyed enemy gun and rear defensive positions in one day—positions it might have taken many days to reduce by ground attack.” He added that “the impact of the airborne divisions at one blow shattered hostile defense and permitted the prompt link-up with ground troops. The increased bridgehead materially assisted the build-up essential for subsequent success.” The drive eastward and “rapid seizure of key terrain,” he concluded, “were decisive to subsequent developments, permitting Allied armor to debouch into the North German plain at full strength and momentum.”

The Canadian paratroopers played an integral part in this success. They accomplished all of their missions, one of their own earning the Victoria Cross in the process. Now, despite their fatigue and the realization that casualties were once again heavy, they were buoyed by the thought that the war was coming to a rapid conclusion and that they had done much to bring this about.

My father in law was in Andy Anderson’s platoon, how do I get details on the platoons history and exploits?