By John D. Gresham

When one thinks back to the weapons of mass destruction that emerged in the 20th century, usually the atomic bomb or poison gas come to mind. But when you tally up the deaths from the world’s wars over the past hundred years, the simple fact is that atomic and chemical weapons created only a handful of casualties compared to more conventional means, such as disease or artillery. Discount these, however, when you take a hard look at mass-casualty generation in the 20th century. The weapon of greatest lethalness is one we often take for granted: the machine gun.

The emergence of rapid-fire weapons in the early 1900s, along with barbed wire and barrage artillery, became one of the dominant reasons for the stalemate in World War I. Mass infantry charges across open ground became a virtual impossibility when faced by dug-in machine guns with supporting troops. Such defensive arrangements almost eliminated battlefield mobility between 1914 and 1918. In fact, it was this kind of defensive arrangement that led to the development of protected vehicles (tanks and armored personnel carriers), air mobility (airborne and helicopter assaults), and even such mundane items as personal body armor. All were designed to counter the military stagnation brought on by machine guns.

Respected and Feared for Over 100 Years

Today the machine guns of the early 20th century still have a role, though very few look like they did a hundred years ago. Improved materials, lighter designs, better ammunition, and other factors mean that most machine guns look like something from the distant future, not the era of the Model T. Note the word “most.” There is, in fact, one machine gun that has been in continuous production and service for almost a hundred years, and is still as respected and feared as it was when first introduced. It arose from the fertile mind of an American designer who became the most respected gunsmith of his age: John M. Browning. His weapon was the M2 .50-caliber, heavy-barreled machine gun.

The development of rifled firearms in the mid-1800s started a race among gunmakers to see who could build weapons that would lay more and accurate fire down on a battlefield. The trend was accelerated during the Crimean War in the 1850s and the American Civil War in the 1860s. Despite the significant improvements brought on by rifled muskets and the massed-formation tactics of the era, soldiers and gunmakers continued trying to find new ways of putting more fire down to break enemy lines in battle. This led to breech-loading and multishot rifles and carbines, such as those from Henry and Spencer. Nevertheless, there was a desire to field a weapon that would have the range, accuracy, and hitting power of a rifled musket, but fire at a rate that would give a single gun the firepower of a whole regiment of soldiers. It was clearly understood that such a device would be a hybrid, firing infantry projectiles but probably having to sit on a carriage like a light artillery piece.

The American Civil War produced a number of such weapons, ranging from so-called “volley” guns that sprayed a number of rifle bullets all at once like a shotgun, to multishot, semi-automatic weapons like the Agar machine gun, which was nicknamed the “coffee grinder” for the way it fed its ammunition. Best known was the famous Gatling gun, which used a rotating series of hand-cranked barrels to spit out around 120 rounds a minute. All of these mid-century guns had limitations, though, ranging from the reload time for the volley guns, low cyclic (firing) rates, and the need for a man to hand-crank the Gatling and Agar weapons. Clearly what was needed was something fully automatic, which might use some form of mechanical energy or power to feed the rounds into the chamber, fire them, then eject the spent cartridges.

10,000 Rounds in 27 Minutes

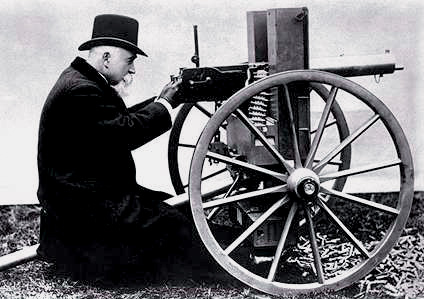

By the end of the 19th century, there were several machine guns that did just that. In 1880 the British Army adopted the Gardner machine gun, which could fire 10,000 rounds in 27 minutes (over 370 rounds a minute). However, it took an American inventor working in Europe, Hiram Maxim, to produce the first machine gun to gain wide service. In 1885, he introduced his machine gun, which used the firing recoil force to eject the spent cartridge, feed the next, then fire another. Maxim’s design was fairly portable, could fire almost five hundred rounds a minute, and had the equivalent firepower of a hundred soldiers with bolt-action rifles. The German and Russian armies bought Maxim’s machine gun. But the United States was skeptical of European-made weapons, even if designed by an expatriate American. It would take an American working in the States to bring America to the age of automatic weapons, and the designer was John M. Browning.

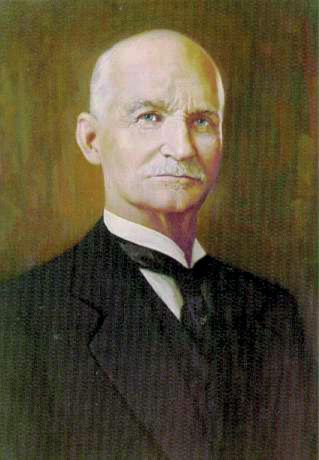

John Moses Browning was born in 1855, grew up in Ogden, Utah, and began working in the family gun business at a young age. Starting with single-shot, lever-action rifles, his designs began to get the notice of the famous Winchester Firearms Company. They bought the rights to his early rifle design and many more in the decades to come. Later he would have similar relationships with Colt Manufacturing and Fabrique National (FN) of Belgium. He enjoyed the designer/manufacturer relationship, knowing that he was much better at designing weapons than manufacturing and selling them. This also left him time to concentrate on new and more advanced designs for firearms, many of which were the envy of the world. These included pump-action shotguns, early .22-caliber rifles, and the immortal M1911 Colt .45-caliber automatic pistol.

In 1895, Browning introduced his first machine gun, which made use of the hot gas from a fired cartridge to drive a piston, which supplied the motive power to eject and load from and to the firing chamber. He had earlier developed this idea while designing an automatic shotgun, and continued to perfect it over several different weapons designs. Built by Colt and adopted by the U.S. Navy, it was in service during the Spanish-American War where it was used extensively in Cuba. It also was adopted by the British and Canadian armies, who used it in various “brushfire” wars during the late colonial era.

Improving the Successful Machine Gun

By the early 1900s, Browning was thinking about ways to improve his 1895 machine gun, especially with regard to weight, portability, cyclic firing rate, penetration, and hitting power. The years before World War I were fairly “lean” from a weapons procurement standpoint, and many of his efforts failed to deliver substantial orders. Nevertheless, by the start of the Great War, he fully understood what he wanted to create: a family of automatic weapons ranging from a personal machine gun (the famous Browning Automatic Rifle, BAR) to an improved version of his 1895 machine gun tooled to fire rifle-caliber (7.62mm/.30 caliber) ammunition, the M1917A1. Both were immediate successes, with improved versions of both serving until they were retired in the 1960s.

The requirement for an even heavier U.S. machine gun was issued in April 1918, apparently at the personal behest of General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing. Based upon U.S. experiences during World War I and the Spanish-American and Mexican interventions, Pershing and the army saw a need for a heavy weapon not only capable of plowing down infantry but also of hitting and destroying new kinds of targets such as aircraft and tanks. It was this thinking that led directly to the development of the M2 .50-caliber heavy machine gun and its family of ammunition. The idea was to throw a .50 inch/12.7mm diameter solid slug from a weapon only slightly larger and heavier than the M1917A1, an impressive challenge and one that John Browning would make into his masterpiece.

What became known as the M2 started on John Browning’s drawing board (working with Colt) as a scaled-up M1917A1. In fact, the two looked almost identical except for the larger size and different firing grips of the .50-caliber weapon. Otherwise, the two weapons shared many common features, including their water-cooled barrels and feed mechanisms. Both were also very heavy, with a water-cooled M2 tipping the scales at over 220 pounds with its tripod and condensation can. To help reduce this to a more manageable weight, Browning adopted an air-cooled barrel (weighing 81 pounds by itself) to get rid of the water jacket and can. Still, the air-cooled M2 still weighed in at a hefty 128 pounds, with the standard tripod adding another 44 pounds. Clearly, the M2 was never intended to be a man-portable weapon, rather being destined for mounting on vehicles, aircraft, ships, and other heavy platforms. Nevertheless, the M2 or, as it was often called, “Ma Duce” (pronounced “Ma Doose,” and combining both the M and 2—“duce,” or two—as well as the thought of “Mother,” or loved one), was a heavy machine gun for the ages, from the start the finest such weapon ever designed.

A ‘Special’ Kind of Ammunition

What made the M2 such an impressive weapon was the bullets it fired. From the very beginning, the .50-caliber rounds designed for the M2 were something special. The term “caliber” in the context of small arms means the diameter of the bore, measured in decimal fractions of an inch. So, in metric terms the M2 is designated as a 12.7mm weapon. Initially, the specifications for the M2 “ball” round were for a simple solid shot, little different in makeup from the .30-caliber round of the M1917A1. For the development of the ball round, the army contracted to Winchester, which began by working from their existing 16-gauge brass shotgun shells. Eventually, work on the .50-caliber round was transferred to the Frankford Arsenal where a number of different designs were tried. Eventually, a modified .30-caliber 30-06 design became the M1924/M2 machine- gun cartridge.

The basic shape of the M2 ball round is almost aerodynamically perfect (“ball” here does not mean spherical but solid, that is, not having a cavity into which chemicals are placed for tracer or explosive use). The form of the .50-caliber round has a slight taper at the bottom, which has the effect of reducing drag and maintaining stability. So perfect is the shape, in fact, that a generation later, when engineers at Bell Aircraft were deciding on the shape for the X-1 supersonic research aircraft that would break Mach 1, they based it on the .50-caliber round of the M2. As an added bonus, the .50- caliber round had enough volume and weight that it could support fillers like a base tracer or an incendiary core, and could be made of various materials including tungsten for armor piercing. Even today, ordnance engineers look in awe and wonder at the vision and genius of the .50-caliber round, designed at a time when slide rules, adding machines, and blackboards were the high-tech tools of the gunmaking trade.

“Ma Duce” first entered service with the U.S. Army in 1919, too late for service in World War I. Nevertheless, the M2 became an instant hit wherever it was installed or deployed, for both its amazing hitting power and range and its genuine simplicity of operation. Much of this derived from the simple recoil operation of the weapon, a signature John Browning design feature. “Recoil operated” means that it uses an ingenious arrangement of levers, cams, and springs to capture part of the powerful recoil energy of the fired cartridge, uses it to extract and eject the spent cartridge case, then to feed the next round, load and fire it.

An Accurate Weapon That Can Hit Targets Over a Mile Away

This cycle repeats as long as the gunner holds down the “V”-shaped trigger located between the two handgrips at the rear of the gun. Release the trigger and a latch secures the mechanism in the “open bolt” position, ready to fire again. In fact, when firing the M2 on full automatic (there are also single-shot and semiautomatic modes), the sensation to the gunner is a lot like riding a classic Harley-Davidson “Hog” motorcycle: The power is something you feel as much as hear and see!

Nevertheless, the M2 is not always an “easy” weapon to possess and maintain. While rugged and well built, it requires a fair amount of maintenance and cleaning, especially in the adjustment of the “headspace” between the rear of the cartridge and the bolt. In addition, the weight and fairly high recoil of the M2 require a sturdy and stiff mount for effective shooting, mandating either the previously mentioned heavy tripod or a secure “pintle” mount tied to the structure of a ship, aircraft, or vehicle.

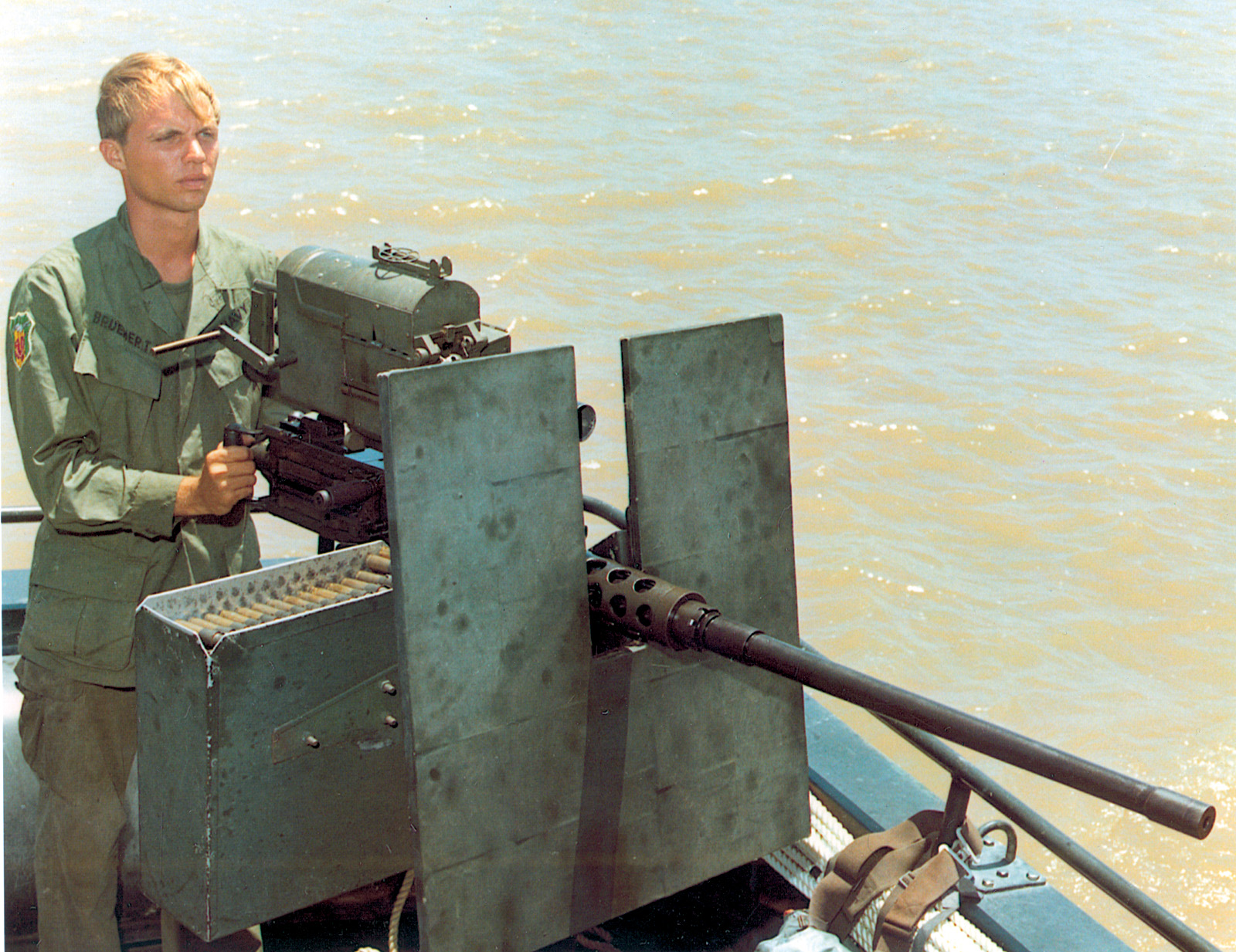

The payoff, though, is a weapon that can hit targets with ease over a mile away, with an accuracy that is often surprising. During the Vietnam War, the legendary Marine sniper Sergeant Carlos Hathcock obtained many of his 93 “kills” at ranges up to 2,500 yards with standard M2 machine guns and a special telescopic sight he carried in his gear. So effective was the combination that, 20 years later, a Tennessee gun designer named Ronnie Barrett would design a lightweight .50-caliber sniper rifle firing the M2 ball round that would become a standard weapon for the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps.

The 1920s and 1930s saw the gradual acceptance of the M2 into every service in the U.S. military, including the Coast Guard. By the start of World War II, the M2 was the standard weapon for U.S. fighter and bomber aircraft, tanks and scout cars, and the primary antiaircraft weapon for naval vessels. As might be imagined, though, the needs of a two-ocean war made for a voracious demand for the M2, which only grew as the conflict went on. For example, B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers each had a dozen M2s as their defensive armament, while six of the .50-caliber weapons became standard for the F-6F Hellcat, F-4U Corsair, and P-51 Mustang fighters. Millions of the .50-caliber weapons were produced and used in every theater of the war. By the end of the conflict, the M2 had become the most produced machine gun of all time, with millions in service around the world.

Even more impressive were the myriad rounds produced for the M2, numbering into the billions. By the start of World War II, the basic M2 ball round (later improved into the M33 configuration) had grown into an entire family of ammunition (see Sidebar).

Nine Decades of Continuous Service

A “normal” mix of rounds for most applications would include two rounds of TP/ball, two of API, and one of tracer in five-round groups, providing a good range of end effects. The ammunition is assembled into belts with reusable spring clips called “disintegrating links” because they are stripped off by the gun’s feeder mechanism. Using the ammunition shown in the sidebar, the theoretical maximum range for the M2 is 4.2 miles, and has actually been used for indirect fire at high angles of elevation to create a “fire beaten zone” on the far side of a hill. The practical maximum range for aimed direct fire is about one mile.

At shorter ranges, the effects are truly amazing. With a rate of fire of between 400 and 550 rounds a minute, .50-caliber rounds from the M2 can literally shred drywall or wooden buildings, or even unarmored vehicles. At favorable angles and ranges it can penetrate the top, side, or rear plating of armored vehicles and aircraft like personnel carriers, infantry fighting vehicles, or attack/scout helicopters. This makes the M2 a very dangerous thing to have in your bag of military tricks, and is why the .50-caliber has remained the love of soldiers, sailors, and Marines in every military force that fields it.

As the M2 enters its ninth decade of continuous service and production, one might think that it is ready for a well-deserved retirement and replacement. However, that assumption is wrong. The basic virtues of the M2 still make it the choice of military professionals all over the world more than 80 years after its introduction to service. The threat of naval terrorism has meant that every U.S. naval vessel now has pintel mounts for a pair of M2s. The guns are still found in heavy weapons units of every Army and Marine Corps formation in service. Long after some guided missiles and nuclear weapons have gone to the boneyard, “Ma Duce” continues to soldier on into a new century, made relevant again by a new era of conventional warfare.

Although the gun never wears out, the United States continues to maintain the tooling and industrial base to produce it. New-production M2s still are being delivered today, the current contractor for the U.S. military being Saco Defense, Inc. (recently acquired by General Dynamics of Maine). Its unit cost is $14,400, cost-effective considering its range, lethality, durability, and simplicity.

As the M2 soldiers on, the fact is that the last M2 gunner has probably not yet been born. This is an almost ageless weapon, whose utility has gone through more wars, engagements, and incidents than historians could probably tally. Nevertheless, “Ma Duce” is still out there, with the kind of reputation and affection usually associated with a new sports car or bass boat by the gunners who man them. It is fitting that she will probably outlive them, too.

My Grandfather Dominic Giglia a .50 caliber machine gun instructer/operater in the WW2 Pacific Front–

me wish to know more about him and fighting group

Dominic passed away:

— 5/10/1980–

My Dad commanded a quad-fifty halftrack in the Korean War.

All the rest of his days, he had nothing but high praise for the sheer firepower of that configuration. I wish I could see it live just once.