By William R. Hawkins

Following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 (and roughly four years prior to the construction of the HMS Cornwall), cruisers became a focus of the interwar naval arms race, no less keenly felt by the British, whose survival depended on the sea-lane. The treaty placed a cap on the total tonnage of battleships each major power could maintain, setting the 5:5:3 ratio between the United States, England, and Japan that became the basis for all subsequent negotiations (Germany at the time was meant to be disarmed; France and Italy’s limits were both set at 1.67 with respect to the above). It also banned new battleship construction for 10 years, a restriction later extended to 1936. These limits terminated World War I construction programs and even required the scrapping of some existing battleships, thus the renewed interest in cruisers.

The treaty was not silent about cruisers. It allowed for their construction, but set an upward bound on their size and armament at 10,000-tons displacement with guns no larger than 8-inch. Thus the Washington system limited naval arms, but did nothing to eliminate underlying national rivalries. The major powers all proceeded to design ships as close to the limit as possible, searching for the optimum mix of firepower, speed, armor, and endurance.

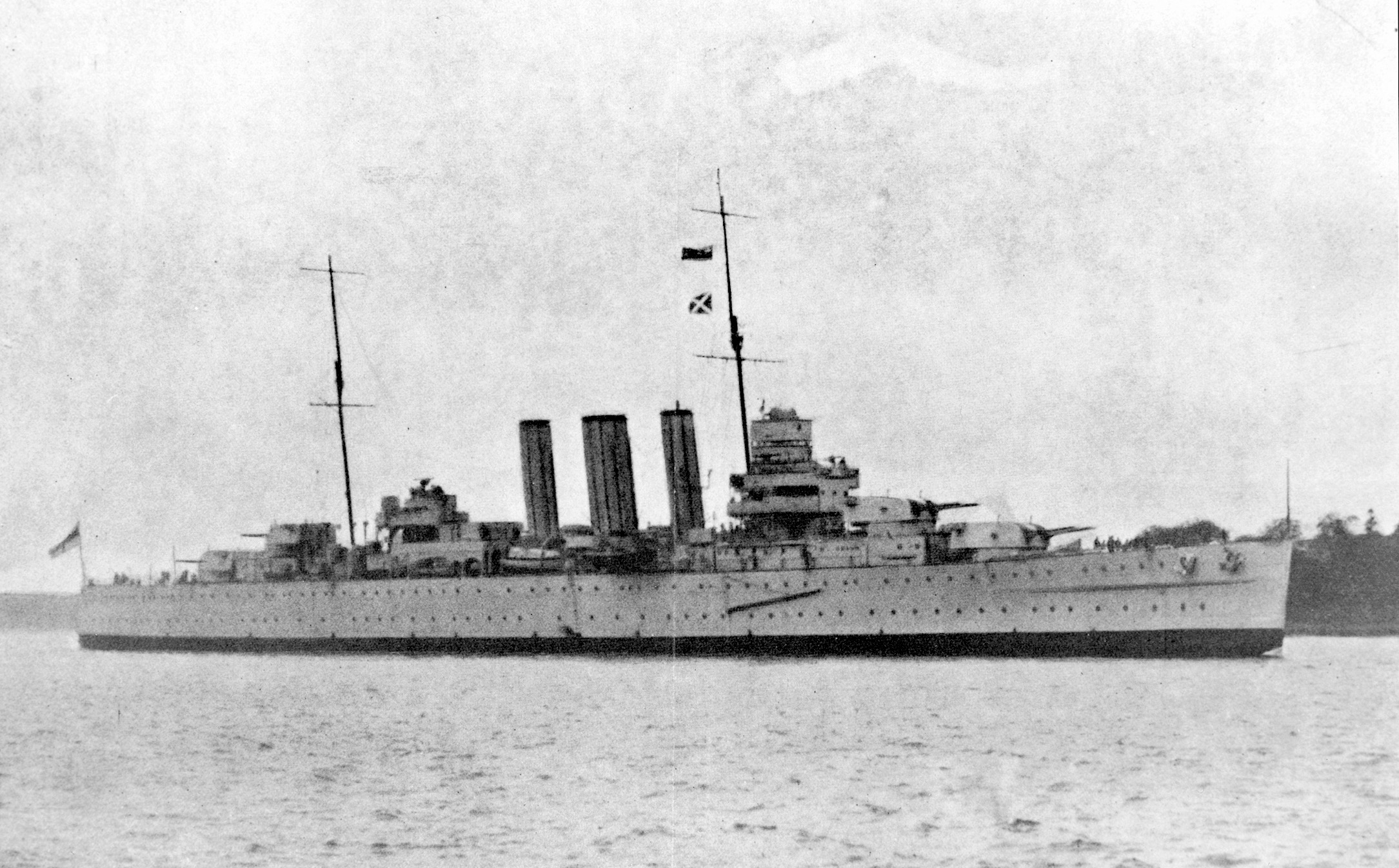

The British had the edge in experience, having already built the Improved Birmingham-class (1917-21); ships of 9,550 tons, with seven 7.5-inch guns, and a speed of 30.5 knots. These ships had introduced the modern cruiser concept, superior in endurance and speed but inferior in armor and gun-caliber to the armored cruisers of the Great War. HMS Cornwall was the first “treaty cruiser” of the County (or Kent) class when launched on March 11, 1926. The original plan had been to build eight of these heavy cruisers, but the Labour government of Ramsey MacDonald elected in 1924 reduced the number to five. The cut was partially offset, however, by Australia’s decision to acquire two of this class for itself.

What Made the HMS Cornwall A Swift and Powerful New Cruiser

The HMS Cornwall displaced 9,750 tons and carried a crew of 679. It mounted eight 8-inch guns in four twin turrets, four 4-inch AA guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes. Maximum sustained speed was 31.5 knots with a range of 7,000 nautical miles at 10 knots on 2,800 tons of fuel oil. Its mission was to guard the global sea-lanes upon which England’s commerce and survival depended. Protection against the 8-inch shells of other heavy cruisers was nil. To stay within the 10,000-ton limit, defense was sacrificed for offense. Some protection for the magazines (3 inches of armor) and engines (1 to 2 inches) was provided against the lighter guns carried by destroyers and armed merchant raiders. Yet even this light armor meant that British cruisers were generally better protected than those of other navies, though somewhat slower as a result.

On a cruise to South America in 1928, Cornwall’s captain reported that the “ship has shown herself excellent on this long voyage, we have experienced rough weather and heavy seas, but only a small amount of damage.… The ship is steady and dry, the only weak part … appears in the stern. The bumping and shaking of the stern in heavy weather shakes the whole ship. The ship is comfortable, both in tropical heat and in severe cold.”

Because scouting and reconnaissance were vital in operations against raiders, it was decided in 1933 to add aircraft to all cruisers. Two were normally carried. Antiaircraft guns were increased before the war by installing dual mounts in place of the single mounts for the 4-inch guns and by the addition of two quad 2-pounder (40mm) “pom pom” guns.

The last of the prewar British heavy cruisers was launched in 1929. The London Naval Treaty of 1930 limited the British Commonwealth to 15 8-inch cruisers against 18 for the United States and 12 for Japan (Tokyo dropped out of the London system in 1936 and had built 18 heavy cruisers by 1939). In compensation for a limit lower than that of the United States, the Royal Navy was allowed a greater tonnage of light cruisers armed with 6-inch guns. The British needed more ships to deploy across the great expanse of ocean covered by the Empire and Commonwealth.

Throughout the arms control negotiations of the interwar period, the United States made a strong effort to reduce the overall size of the world’s navies. This was particularly true under President Herbert Hoover who, in his meetings with Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald in October 1929, made disarmament proposals that even the Labour leader found extreme. The British Empire became the main victim of these American efforts.

A Heavy Workload for a Light Ship

Even before the 1930 treaty, London had decided it could not afford large numbers of heavy cruisers and had shifted in 1928 to the construction of the smaller ships of the Leander and Arethusa classes. Plans to build eight more heavy cruisers during the years 1927-29 were canceled. Even the last two 8-inch cruisers, York and Exeter, were smaller than the preceding heavies, displacing only 8,250 tons with six 8-inch guns instead of eight.

While Admiralty spokesmen continued in public to express confidence in the ability of British sailors to outfight ships of superior firepower, in private there was growing concern that the Navy’s new light cruisers could not stand up to the larger ships being built by potential enemies. It was not that British light cruisers were inferior for their class; they were generally larger and better armed than Italian, Japanese, or German light cruisers. The problem was that British light cruisers were being built to perform duties that should have been assigned to heavy cruisers.

The 1934-36 programs tried to deal with this by building the eight Southampton-class cruisers. These marked a return to the 10,000-ton limit, but were still armed with 6-inch guns—12 of them in four newly designed triple turrets. But like the earlier heavy cruisers, these were considered too expensive by the Exchequer. Thus the British continued to place their faith in arms control. Having won in the 1930 London Naval Treaty a moratorium on 8-inch cruiser construction, an 8,000-ton limit on cruiser displacement was agreed to in the second London Naval conference of 1935.

However, because Germany had not participated in the conference and Italy and Japan had walked out of the talks, the 1935 agreement ended up being a self-limiting agreement among the three Western democracies: England, France, and the United States. Thus the Axis powers were free for a time to build larger and more heavily armed warships than their future opponents. In 1937, both America and England discarded the treaty limits and began rearmament programs.

Starvation Number: 50

The British Admiralty had determined that 70 modern cruisers were needed, 45 for trade protection and 25 for the battle fleet. This was a considerable reduction from the 114 cruisers available in 1914. When war broke out in 1939 the Royal Navy (including Commonwealth ships) numbered 67 cruisers, but only 42 were modern ships launched during the preceding 15 years. This was an even lower number than the minimum of 50 modern cruisers that had been set by the Labour government in 1930 in the name of peace and fiscal restraint.

The First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Charles Madden, had termed 50 cruisers a “starvation number” in 1929. In a 1931 memorandum drawn up in preparation for the League of Nations World Disarmament Conference (held without result in Geneva during 1932-34), Madden’s successor, Admiral Sir Frederick Field, stated that the Commonwealth “has accepted a naval strength which, in certain circumstances, is definitely below that required to keep our sea communications open in the event of our being drawn into a war.”

Although the Admiralty won reacceptance of the 70-cruiser goal when the Conservatives returned to office in 1931, the tight budgets of the 1930s prevented that goal from being attained. For the six years before becoming the prime minister best known for appeasement, Neville Chamberlain had served as Chancellor of the Exchequer. There he had fought successfully to minimize military spending in the name of low taxes and balanced budgets. A more fundamental problem was the decline in the naval shipbuilding industry as a result of curtailed procurement. Of the 12 major firms involved in naval construction in 1914, five were out of business by 1933 and five others were down to skeleton staffs. The merger of Vickers and Armstrong created the only firm capable of fulfilling large orders across the spectrum of military needs. This downsizing of the industrial base made rapid rearmament impossible.

The HMS Cornwall Sinks the First German Raider

In order to boost the number of ships in the fleet within the treaty and fiscal limits, 11 of the small (5,450 tons) Dido-class ships armed with 10 5.25-inch, dual-purpose guns were ordered in the 1936-38 programs. Thus in 1939 the only heavy cruisers afloat were those built in the 1920s.

The HMS Cornwall was assigned to the 5th Cruiser squadron on the China station (Hong Kong) when the Germans invaded Poland. That may have seemed safe, but it was soon apparent that at least on the naval side it was going to be another global conflict.

Cornwall, along with the heavy cruiser Dorsetshire and the small aircraft carrier Eagle, were formed as Force I at Colombo, Ceylon, one of eight hunting groups created to corner the German pocket-battleship Admiral Graf Spee. The Graf Spee turned toward South America, however, and the Cornwall did not participate in its destruction.

Cornwall, however, did have the honor of being the first to sink one of the dangerous German armed merchant raiders, the Pinguin under Kaptain Ernst-Felix Kruder. A sister ship to the famous Atlantis (sunk by HMS Devonshire on November 23, 1941), Pinguin was a converted 7,600-ton cargo liner built in 1936. It mounted six 5.9-inch (150mm) guns, one 75- mm gun, and four 21-inch torpedo tubes in two above-water twin launchers as well as 37mm and 20mm AA guns. She also went to sea carrying several hundred mines. For reconnaissance, she had one Arado Ar 196 seaplane.

Pinguin made its first kill July 31, 1940 off the coast of West Africa, then laid mines off the coast of Australia. With a range of 60,000 miles at 10 knots, Pinguin was designed for long-distance operations and, except for an attack on the Norwegian whaling fleet in Antarctica in January 1941, plied the Indian Ocean from August 1940 into May 1941.

Cornwall, under the command of Captain P.C.W. Manwaring, often operated in the western Indian Ocean despite still being assigned to the South Atlantic Command. On April 29, the 7,266-ton liner Clan Buchanan got a message off before being boarded and scuttled by Kruder’s raider. Force V, consisting of Cornwall, the old cruiser Hawkins, and the carrier Eagle, was ordered to respond, as was the New Zealand-manned 6-inch cruiser Leander. Kruder headed west toward Africa rather than south to open sea where the British were looking. On May 7, however, 300 miles southeast of Socotra, Pinguin tried to capture the small 3,600-ton tanker British Emperor. The victim did not cooperate and raised an alarm heard both by Cornwall sailing from Mombassa and by British authorities in Colombo. Captain Manwaring increased speed to 25 knots (Pinguin’s top speed was 16 knots) to intercept the raider that was then 500 miles north of his position. Kruder obliged by turning southwest so that the two ships spent the day and night closing the distance between them.

Only 60 Men Survived

At 7 in the morning on May 8 one of Cornwall’s Walrus seaplanes spotted Pinguin 65 miles off the port side and the chase was on. The cruiser increased speed to 28 knots. Unable to escape, Kruder tried to brazen out his disguise as the Norwegian merchantman Tamerlane, even sending out a false raider report over a captured British radio. Manwaring twice challenged and twice fired warning shots after pulling within visual range at 4 pm. As the cruiser closed to 10,500 yards, the German turned to port, hoisted its true colors, and opened accurate fire with its 5.9-inch guns. A hit disabled Cornwall’s steering for several minutes and the forward A and B turrets had to be shifted to manual control owing to a circuit failure.

Cornwall moved to open the range as near misses showered the ship with splinters. Pinguin also fired two torpedoes that missed. Once the cruiser was able to bring all its 8-inch guns into action, the battle ended quickly. At 5:26 a four-gun salvo hit the raider. One shell hit forward, another under the bridge, a third in the engine room, and a fourth detonated some of the 130 mines still on board, causing a massive explosion that sent the raider under in seconds.

Only 60 out of the Pinguin’s crew of 342 and 22 out of 225 Allied prisoners held on the raider survived. Kaptain Kruder was not among them. Rescue operations were hampered by the failure of electrical power in the Cornwall’s engine room, causing so much heat to build up that the engineering spaces had to be temporarily abandoned and one officer died of heat stroke.

Uneven Contest or Fair Fight?

While a battle between a heavy cruiser and a raider may seem an uneven contest, it must be remembered that raiders packed considerable firepower at close range. This is where most engagements were fought owing to the need for British captains to make a positive identification of suspected ships before opening fire.

While the Royal Navy guarded against German raiders in the Indian Ocean, it also had to keep an eye on Japan. Tokyo had proclaimed its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere on July 27, 1940. Less than four weeks before the Pinguin was sunk, Japan had signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union. This protected Tokyo’s back as it prepared an attack to the south.

The blow fell on the British as well as the Americans on December 7, 1941 when Japanese troops landed on the Malayan peninsula. Three days later the battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse (Force Z) were sunk by air attack. By the end of January 1942 the Japanese Army was at the gates of Singapore, which surrendered on February 15.

The oil-rich Dutch East Indies were the next Japanese target. On February 27 and 28, a mixed American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) force of five cruisers and nine destroyers attempted to intercept a Japanese invasion force. In the resulting Battle of the Java Sea, all the ABDA cruisers were lost including the British heavy cruiser Exeter which had won fame for its duel with the Graf Spee in the River Plate.

By April the Japanese had digested their Pacific conquests and were prepared to mount a major raid into the Indian Ocean. Vice Admiral Nagumo had five of the six large aircraft carriers he had used at Pearl Harbor with a covering force of four battleships, one light carrier, three cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

The British fleet was under Admiral Sir James Somerville who had only recently become C-in-C of the Eastern Fleet. He had distinguished himself in the pursuit and destruction of the German battleship Bismarck and as commander of Force H in the Mediterranean. Somerville divided his fleet into two groups: Force A (two fleet carriers, one battleship, four cruisers, and six destroyers) and Force B (four battleships, one light carrier, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers). The battleships and cruisers of Force B were too old and slow to face the cream of the Japanese fleet. Somerville hoped to surprise the enemy with the more modern ships of Force A, to which Cornwall was assigned.

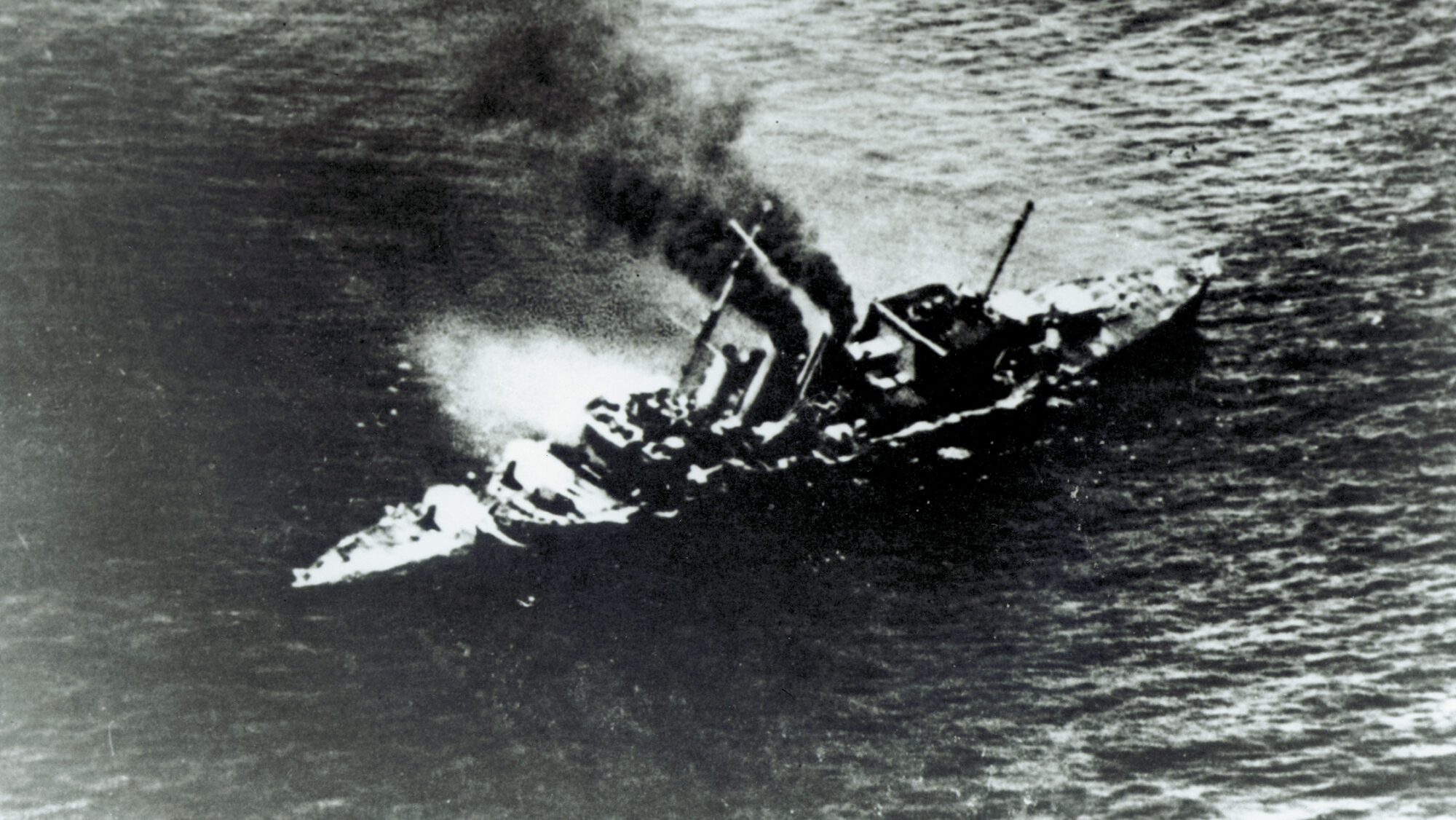

When Nagumo was sighted headed for Ceylon on April 4, Force A was divided. Cornwall and Somerville’s only other heavy cruiser, Dorsetshire, were at Colombo while the rest of the fleet was refueling 600 miles to the southeast at the secret British base of Abbu Atoll in the Maldives. The cruisers were ordered to rendezvous with Somerville and were thus away from Colombo when the Japanese air strike hit the base on April 5, Easter Sunday. Their luck changed for the worse when a reconnaissance floatplane from the Japanese cruiser Tone spotted the two British warships just as the Colombo attack was ending. Both cruisers were in need of a refit and could only make 27.5 knots in their attempt to put distance between themselves and the enemy.

”Abandon Ship!”

At 11:30 Nagumo ordered his remaining dive-bombers to attack the cruisers. Nearly 80 “Vals” dove out of the sun at 1:40 pm. Cornwall took a hit and two near misses on the first pass, then Dorsetshire took a hit that jammed her steering gear, sending the ship in an uncontrollable circle. Four minutes later, another bomb found one of her magazines. Shattered by the explosion, the ship lost speed and took on a list. Then four more bombs hit. Captain Augustus Agar, a holder of the Victoria Cross, ordered the ship abandoned. Eight minutes after the attack started, Dorsetshire sank by the stern.

Cornwall did not last much longer. The cruiser took at least seven hits and numerous near misses that also did considerable damage. The after engine room and both boiler rooms were flooded and electrical power was disrupted. The forward engine room took a direct hit as did the sick bay. With a list to port and fires raging out of control, Captain Manwaring ordered “abandon ship” at 1:58 pm. Cornwall capsized four minutes later. Only one “Val” had been shot down.

With the Cornwall were lost 10 officers and 181 men, and with the Dorsetshire 19 officers and 214 men. Among the dead were many of the South African volunteers who had done so much to make up for manpower shortages in the Royal Navy. There had been 104 such volunteers on Cornwall and 84 on Dorsetshire. Yet, 22 officers, including both captains, and 1,100 men were rescued the following evening by the light cruiser Enterprise and two destroyers after enduring 30 hours in shark-infested waters.

Admiral Somerville had detected the Japanese dive-bombers on the radar of his flagship, the battleship Warspite, and immediately turned away from the threat. Admiral Nagumo, having revealed his position by his attacks on Colombo and on the cruisers, also turned away. Vice-Admiral Ozawa’s cruisers and destroyer spent the next two days raiding Allied shipping. Three days after sinking Cornwall and Dorsetshire, Nagumo’s planes found and sank the light British carrier Hermes and its two escorting destroyers outside Trincomalee. The next day, Somerville abandoned the seas east of India; Force B heading for safety at Kenya and Force A heading for Bombay.

The HMS Cornwall’s Legacy

Four of the five heavy cruisers lost by the Commonwealth during the war were sunk by the Japanese. British 8-inch cruisers on distant stations, though few in number, performed well against the surface raiders sent out by Germany, a country that was not a great naval power. But the interwar emphasis on arms control and economical defense budgets had left the Royal Navy without the means to confront a first-rate seapower like Japan in a clash of battle fleets. The problem was not, of course, just an inadequate cruiser force. The same interwar policy had left the Royal Navy with a primitive Fleet Air Arm, a destroyer shortage, and an over-reliance on obsolete capital ships.

It was the Royal Navy’s ability to project power into distant seas on a regular basis that had transformed England from a minor island nation into a global empire and arbiter of world events. For 16 years the heavy cruiser HMS Cornwall was a symbol of that British power; yet at the same time it was a symbol of Britain’s decline. The first cruiser designed under the terms of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, when the world seemed at peace, the Cornwall became the victim of Japan’s rising power 20 years later. The Cornwall’s eventful service on distant stations traced the loss of that pre-eminence at sea that the Royal Navy had held for two centuries. (Read more about the naval advancements and strategies that defined the Second World War inside WWII History magazine.)

my father was on the Cornwall as a royal Marine

My father, at the time, Colour Sergeant Ian Armstrong Marsh, was also on the Cornwall as a Royal Marine. He was trapped below decks when the hatches were all closed during ‘battle stations’. He was saved by an officer whose name I forget, who came back and let some of the men out as she was sinking. He spent many hours clinging to a table top before transferring to a lifeboat and then being rescued and taken to Trincomelee. He died in March 2013 aged 93. He was extremely proud of his years with HMS Cornwall and had many a tale – of “being chased round the far east by the Japanese” – to tell till the very end!

Hi Tony my dad was,a survivor from HMS Cornwall in 1942.Do you have any photos of your dad or the ship I can put on my remembrance page. Plus any stories

Thank you

David Malcolm