By Eric Niderost

On March 17, 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte closeted himself in his study at the Tuileries Palace in Paris and ordered his private secretary, Louis Fauvelet de Bourrienne, to unroll a large map of Italy and lay it on the floor. Bonaparte was First Consul of the French Republic, head of a new government that had been installed the previous November, but he was still only 30 and didn’t stand on ceremony. Once the map was on the floor Bonaparte lay on top of it; Italy was not only at his feet, it was under his knees.

The First Consul was a short man, only five-foot-six in height, but he acted with the sure authority of a man born to command. Thin, almost wiry, his uniform fit him well, and the corpulence of his later career was still in the distant future. The aquiline nose and high forehead gave his face an almost Roman cast and his long locks had been recently cut short, earning him the nickname “Le Tondu” (the shorn one).

But above all it was his eyes, blue-gray and commanding, that set him apart from ordinary mortals; a mere glance of displeasure could reduce subordinates to abject terror, a look of approval was better than the highest honor. Right now Bonaparte’s eyes were fixed on the map of Italy that was spread before him. After a moment’s deliberation he stuck pins in the map. The pins with black wax tips were enemy formations, and red wax pins marked where Bonaparte hoped to place his own troops.

France had been convulsed by a decade of revolution, a period of turmoil and bloodshed, idealism and reform. By 1800 the revolutionary “fever” had broken, leaving the country drained and weakened by its long ordeal. The French economy was in chaos, its ports blockaded, and its roads infested with brigands. The treasury was empty, and its legal system cried out for reform.

But before Bonaparte could even begin to consider rebuilding France he had to deal with the overriding issues of war and peace. The country was war-weary and looked to Bonaparte to secure a lasting peace with its neighbors. In 1800 France was fighting a powerful Second Coalition composed of Great Britain, Austria and Russia. Russia had effectively withdrawn from the fighting late in 1799, but Austria—backed by Britain’s powerful Royal Navy and British gold—was still a formidable land adversary. French peace overtures were soundly rebuffed; even Bonaparte’s personal appeals to Britain’s King George III and Austria’s Emperor Francis II fell on deaf ears.

The Austrians in particular were in no mood to be conciliatory. They had overrun Italy in 1799 and destroyed the French-backed Cisalpine Republic in the northern part of that country. Dealing from what they thought was a position of strength, the Austrians spurned Bonaparte’s proffered olive branch. Great Britain, too, was in no mood for peace. The First Consul had no choice but to turn his thoughts to war.

Poring over his map, Bonaparte could see possibilities in an apparently hopeless situation. In southern Germany a large Austrian army of over a hundred thousand men under General Kray confronted Gen. Jean Victor Marie Moreau’s Army of the Rhine. In northern Italy, Austrian Gen. Michael Melas opposed a weak French Army of Italy under Gen. Andre Massena. In fact, thanks to Massena’s earlier victory at Zurich, the French still held most of Switzerland, and in Bonaparte’s eyes that country was the key to victory.

Switzerland occupied a central position between Germany and Italy, in essence connecting two seemingly disparate fronts. Bonaparte’s ultimate objective was the destruction of the Austrians in a great battle: Either Kray’s or Melas’s armies would suit his plans. As events unfolded, Melas and Italy were to be the main French target, with Moreau’s Army of the Rhine in a secondary role as a buffer protecting the French left against Kray’s possible intervention.

It was all incomprehensible to his secretary Bourrienne, so Bonaparte motioned him down to the floor to explain. “Where do you think I shall beat Melas?” Bonaparte queried his puzzled scribe.

Bourrienne responded with the honest answer, “How the devil should I know?”

Slightly exasperated, Bonaparte continued, “Melas is at Alessandria with his headquarters… Crossing the Alps here [he pointed to the Great St. Bernard pass] I shall fall on Melas, cut off his communications with Austria, and meet him here on the plains of Scrivia.” As Bonaparte explained his concepts he put a red pin at San Giuliano. Other towns and villages in the area included Villanova and Marengo.

It was a typically Napoleonic conception, simple in design, yet brilliant and audacious in the extreme. Yet, was Bonaparte’s prediction uncanny foresight, or merely wishful thinking? Only time would tell.

Napoleon’s Plan To Raise a New Army

Massena’s Army of Italy was hungry, ragged, and weak, and certainly in no condition to take on Melas alone. Its very plight would make it tempting bait, blinding Austrian eyes to French movements in their rear. Bonaparte planned to raise and equip a new formation that was to be called the Army of the Reserve. Led by Bonaparte personally, the Army of the Reserve would cross the Alps and fall upon Melas before he knew what was happening.

There were some problems in this budding plan of campaign, but to Bonaparte obstacles were made to be overcome, not fretted over. The Constitution of the Year VIII expressly forbade the First Consul to command armies outside of France, so Bonaparte resorted to a legal fiction: His chief of staff Alexandre Berthier was made the nominal chief of the Army of the Reserve. Raising this new army was no easy task at first because few troops were available. Assembling around Dijon, the Army of the Reserve grew steadily from 30,000 to 60,000 men.

But before Bonaparte’s plans could be implemented the Austrians turned the tables by launching a major offensive in Italy on April 5, 1800. General Melas, heavily reinforced, was to sweep down and defeat Massena’s scarecrow Army of Italy, capture Genoa, then invade southern France. The ultimate objective was the great French naval base at Toulon on the Mediterranean. On paper the scheme was admirable; certainly, such a Mediterranean strategy would allow the Austrians to be supplied and supported by the ships of the British Royal Navy.

Unfortunately for the Austrians, the Auric Council—their decision-making body for war—took little serious account of the growing Army of the Reserve assembling around Dijon. In Austrian eyes the Army of the Reserve was an amorphous body, seemingly neither fish nor fowl. Since it was scratch-built and had many raw, inexperienced troops, the Austrians tended to dismiss it out of hand.

Nevertheless, in its early stages the Austrian offensive in Italy met with considerable success. General Massena was a tough and talented soldier, but his outnumbered forces were forced to fall back under heavy Austrian pressure. Eventually the Army of Italy was cut in two, with part of it under Massena besieged in Genoa and the remainder under General Suchet pushed westward beyond the Var River.

All now depended upon the doughty Massena. By the third week of April, the general and 24,000 men were holding on in Genoa, the Austrians laying siege on land and the British blockading them by sea. It was a grim situation, and the prognosis was anything but rosy. The Genoese population was restive, even hostile, and so in a sense Massena was beset with enemies inside and out. Yet the general’s continued resistance delayed the projected Austrian invasion of France and, better yet, tied down a substantial number of Melas’s overall forces.

Bonaparte realized Massena could still play a crucial role in the campaign simply by holding out as long as humanly possible. In fact Massena’s resistance was more vital than ever, because he distracted Austrian attention from the Army of the Reserve. The First Consul was going to move his army through the Alps and fall on Melas’s rear, just as he told Bourrienne. But plans, however brilliant on paper, can fail in execution. Everything depended upon timing.

The First Consul needed a victory, not just to end the war but to secure his hold on power. Bonaparte was unproven as a ruler, his government embryonic. One false step might prove abortive and his regime could be swept away. A decisive victory would be the bedrock that would help to stabilize his government and assure the continuation of his power.

General Moreau resented Bonaparte’s sudden rise to prominence, and it’s likely he saw himself as better suited for the role of France’s ruler. The First Consul wanted him to attack Kray, but Moreau found plenty of excuses to delay action. The Army of the Rhine belatedly took the offensive on April 25, and by May 3 Moreau had defeated the Austrians at Stockach. With Moreau’s victory, Bonaparte’s left flank was secure from any unexpected Austrian intervention from Germany. Plans to cross the Alps could now proceed apace.

The Alps were a formidable barrier any time of year, but in May the passes were still clogged with ice and snow, rending them well-nigh impassible. Some of these mountain tracks might just be barely passable by infantry or even cavalry, but certainly not artillery. Yet that is exactly what Bonaparte proposed to do—bring his entire army over the jagged snow-capped peaks and on to the fertile plains of Piedmont and Lombardy.

Quite apart from the sheer physical exertion it would take to climb the mountains, there was the ever-present danger of avalanche. General Marescot, the army’s chief engineer, reported, “It is vital to take precautions against avalanches which can bury several battalions in a flash.”

Bonaparte had to choose a pass to cross the Alps, and he had several options: From east to west, the St. Gotthard, the Simplon, the Great St. Bernard, and the Little St. Bernard. The St. Gotthard was the most attractive, at least on paper, being wide enough to accommodate an entire army, but it was the farthest east. In the end Bonaparte chose the Great St. Bernard because it was closest to his forward base at Villeneuve on Lake Geneva.

It was a matter of sheer logistics; supplies would be ferried from Geneva to Villeneuve via the lake. Yet the Great St. Bernard seemed the worst of choices—a narrow, steep, and snow-clogged artery that was impassible for regular artillery or wheeled traffic.

The French army was used to living off the land, but there was little in the Alps but ice and snow. It was, therefore, imperative that the Army of the Reserve cross the mountains as quickly as possible. Bonaparte estimated the Alpine trek could be completed in eight days; the soldiers carried nine days’ rations in their knapsacks.

To avoid excessive crowding, and also to throw a smokescreen into enemy eyes, some French detachments took routes other than the Great St. Bernard. General Chabran’s division, for example, was to use the Little St. Bernard, linking up with the main body at Aosta. But the bulk of the Army of the Reserve would pass through the Great St. Bernard.

Gen. Jean Lannes led the way with an advance guard of 8,500 men. The pass was every bit as formidable as anticipated; sometimes it was only 18 inches wide. And so the Army of the Reserve began its celebrated passage through the Alps. The soldiers marched single file along the rough track, a thin blue ribbon against a looming backdrop of granite peaks. At times the defile was scarcely more than a goat trail—rocky, precipitous, and choked with snow and ice. Yet in spite of the difficulties the sweating, hard-breathing troops made good progress. Higher the soldiers climbed, the massive white-mantled mountains growing ever larger, until their pinnacles seemed to spike the sky. The granite behemoths were awesome to behold, but survival, not contemplation, was paramount in the French soldiers’ minds.

In some places the track grew so steep its sides fell away into deep gorges. The infantry gingerly picked its way over the rocky defile, and the cavalry led its frightened mounts on foot. But the toughest job was reserved for those infantry who were selected to carry the artillery over the mountains. There were two methods of transporting artillery. First, the gun carriages were disassembled, and then the eight-pounder cannons themselves were put in hollowed-out tree trunks in the form of troughs. Mules were scarce, and according to some accounts the local peasantry took to their heels, so there was nothing to do but enlist the soldiers as beasts of burden.

Pvt. Jean-Roche Coignet of the 96th Demi-Brigade was a young soldier just starting out on a distinguished military career. In his memoirs he recalls what it was like to drag cannon through the Alps. There were “forty grenadiers to each gun; twenty to drag the piece, and twenty others who carried the others muskets and the wheels and caissons of the piece.” Each drag-team of soldiers was commanded by a cannoneer. It was a grim and back-breaking journey, and Coignet was on the edge of a deep cliff, “next to the precipice.”

“They Were Discovered, Almost Dead with Cold, by the Dogs”

The army snaked its way up to the Col, some 8,120 feet above sea level, then continued on the downward slopes. Their fatiguing journey was refreshed by a brief stop at the Monastery/Hospice of St. Bernard. The monks set up tables laden with cheese and wine, which were gratefully consumed by the French troops as they trudged past. The good monks were famous for their alpine rescues via their celebrated St. Bernard dogs. According to the memoirs of Constant, Bonaparte’s valet, some young soldiers strayed from the main trail and floundered in the snow, where “they were discovered, almost dead with cold, by the dogs … transported to the Hospice … and speedily returned to life.”

The French were making excellent progress, but then their descent into the valley of Aosta was blocked by Austrians at Fort Bard. Bard was virtually impregnable to direct assault. Commanded by an officer named Bernkoff and manned by four hundred grenadiers of the Kinsky Regiment, this tiny garrison held up ten times its number of Frenchmen and effectively corked the narrow “bottleneck” of the valley.

Lannes bypassed Fort Bard by blazing a trail that climbed around the brooding bulk of Mount Albaredo. It was a tough trek, but the advance guard infantry and cavalry managed to clamber up and around the slopes and skirt the fort. Once past Bard, Lannes pushed on, but some forces remained to besiege the stubborn Austrian garrison. The fort had to be reduced, the “cork” removed from the “bottle,” or Bonaparte’s timetable was in serious trouble. The bulk of the Army of the Reserve was held up, stalled in the mountains and forced to consume its precious rations. There was a real danger that the army, as Bonaparte put it, would be “exposed to dying of starvation in the valley of Aosta.”

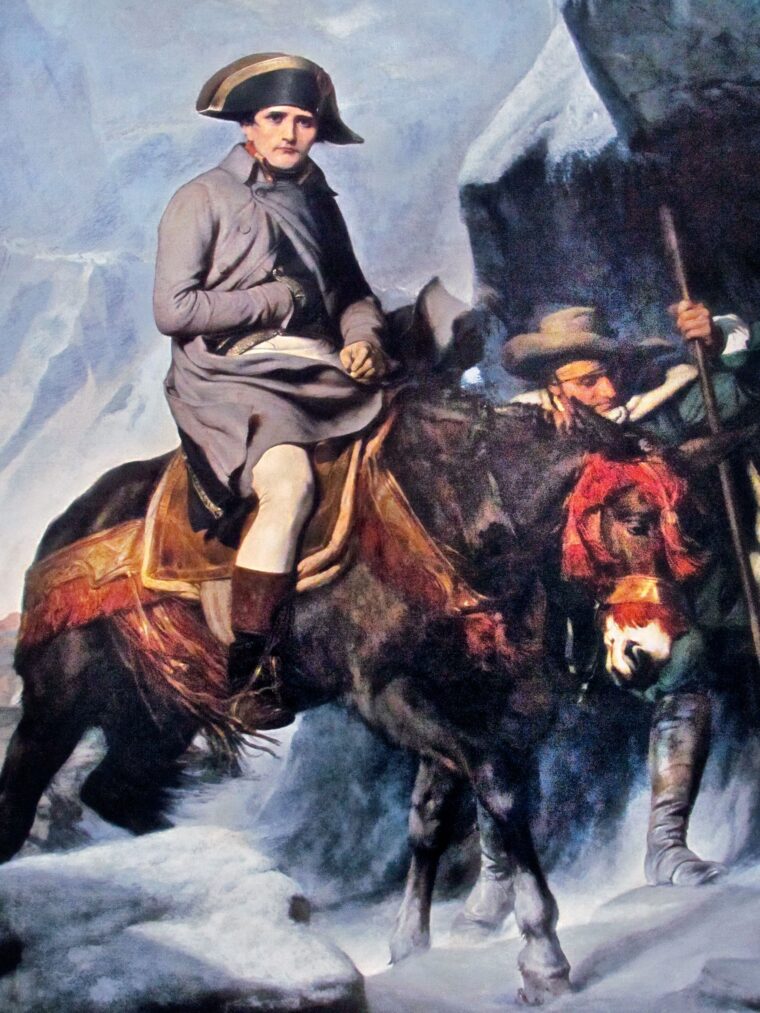

Meanwhile Bonaparte and his entourage had started up the Great St. Bernard pass on May 20, a few days behind the advance guard. The First Consul crossed the Alps on a sure-footed mule, not the painter David’s romantically rearing charger. At tim

es he went on foot, gray greatcoat buttoned against the cold. Once or twice the French soldiers had to slide down snowy slopes like children, and Bonaparte was no exception. Rolling, tumbling, sliding from side to side, the First Consul of the French Republic careened down the icy slopes like a human toboggan, his suite following suit. Far from being embarrassed by the episode, Bonaparte wrote an account of it in his official dispatches.

Lannes reached Ivrea by May 22, so the advance elements of the Army of the Reserve were through the Alps and spreading through the plains of Piedmont. Although French infantry and cavalry were just managing to squeeze past Fort Bard, the artillery and ammunition wagons were effectively blocked. During the night of May 26-27 six cannon sneaked past Bard, the hoofs of the gun team horses wrapped in straw to muffle sound. But the bulk of the artillery was still held up.

Bonaparte pushed on, and he proudly wrote his brother Joseph, “We have fallen like a thunderbolt.” The First Consul had every right to be pleased: The 40,000-man Army of the Reserve, though very weak in artillery, was safely in Italy. But there was not a second to lose, because Massena’s heroic defense of Genoa could not last much longer. Rations were so scanty they barely sustained human life. The garrison and townspeople ate horseflesh and a nauseating “bread made from sawdust, bran, straw, and a tiny trace of flour.”

Eating Horses, Dogs, Rats, and Grass

When there were no more rations, horses, pigeons, cats, and dogs were consumed—anything to assuage the terrible hunger pangs. Rats became a staple, and even grass. Only Massena’s iron will kept the French going, yet it is said that the strain of those terrible weeks of famine left its mark on the general, and his hair turned gray. Starving citizens threatened to revolt; only harsh martial law kept them in check.

Massena was doing his job. He was distracting the Austrians from the approaching Army of the Reserve, and in the process also tying up a good portion of Melas’s troops. Melas began to sense that something was afoot, and by May 19 realized the Army of the Reserve really did exist. But where was it? There seemed to be French activity along a broad front, from the Var River to the St. Gotthard Pass. On May 24 Melas received a dispatch from Fort Bard that thousands of French troops were on the march through the Great St. Bernard. But the intelligence was too late, because the Army of the Reserve was already well ensconced in Italy.

Melas had lost a great opportunity. If he had not been so preoccupied with the Genoa siege and his own projected invasion of southern France, he could have easily blocked all the Alpine passes with heavy concentrations of troops. Bonaparte’s great plans would have been neutralized, his army stuck in the mountainous valleys of the Alps. Once Massena was forced to capitulate, the Austrian invasion of France might continue with little opposition. It was a frightening scenario for the French, but luckily it did not come to pass.

Bonaparte now ordered his forces to Milan, the great metropolis on the Lombardy plain and the former capital of the Cisalpine Republic. Milan was astride Melas’s line of communications as well as a major Austrian base bursting with stores. There were also political advantages to consider; the capture of Milan would be a bloodless victory that would not go unnoticed in Paris. The First Consul’s political stock would rise and his fledgling rule given a boost that it really needed.

When Bonaparte entered Milan on June 2, the populace thronged the streets and acclaimed him with tumultuous cheers. There was more good news when word reached Milan that Fort Bard finally fell on June 1. Artillery and supplies could now flow through the St. Bernard unimpeded. During his six-day sojourn in Milan, Bonaparte the general seemed replaced by Bonaparte the First Consul and consummate politician. He addressed the catholic clergy and even attended an opera at the famed La Scala. But beneath the surface Bonaparte was acutely aware of his military responsibilities. The great Po River was between him and Melas; it was essential that the French establish a bridgehead across the river.

On June 4 Genoa finally capitulated, but Massena managed to procure very favorable terms. The French garrison was not to be taken prisoner, but instead would be allowed to withdraw beyond the Var, there to reunite with their Army of Italy comrades under General Suchet. Once beyond the Var, Massena would be free to resume operations again.

In the meantime Melas was busy concentrating his forces at Alessandria, a movement that had begun as early as May 31. Bonaparte’s anxiety was increasing, but on June 7 Gen. Joachim Murat crossed the Po and seized Piacenza on its southern bank. Once Piacenza was secured the French lost no time in building a pontoon bridge over the river. Soon other bridges were completed, and by June 10 long columns of blue-clad Frenchmen were trudging across the Po. Lannes, in the forefront as always, encountered a force of 18,000 Austrians under General Ott at Montebello and defeated them.

Lannes had gained a notable victory, but the clash was only the curtain-raiser of the unfolding drama. By nightfall of June 11, around 28,000 men had gathered at the concentration point at Stradella, but the French columns were finding it slow going due to heavy rains. A campaign that had begun with such promise was literally bogging down, diluted by the incessant downpour. Even the First Consul was “under the weather,” complaining to his wife Josephine, “I have a wretched cold.”

But Bonaparte’s spirits were lifted when Gen. Louis Desaix joined the Army of the Reserve. Desaix had been in Egypt and had been recently repatriated to France. Bonaparte’s joy in seeing him was real, not feigned; he looked on Desaix as a true friend, not a rival for power. The First Consul at once created a Corps d’ Armee (Army Corps) for Desaix composed of Boudet’s and Monnier’s divisions.

But satisfaction was soon replaced by new anxiety: Where was Melas? So far, apart from one or two isolated clashes such as Montebello, the Austrians seemed to be playing will-o’-the- wisp. The whole object of the campaign was to gain a decisive victory—but how could that victory be achieved if there were no enemy to fight?

Determined to come to grips with his elusive foe, Bonaparte ordered Lannes, Victor, and Murat across the Scrivia river and to head east in the direction of Alessandria. The Austrians seemed to be withdrawing, deliberately avoiding contact. Melas was probably around Alessandria, but Bonaparte reckoned the Austrian had no more than 22,000 men under his command. Melas was indeed in Alessandria, but with 33-35,000 men. It was a miscalculation that would lead to a series of near-fatal errors.

The First Consul became convinced the Austrians were trying to give the French the slip. If so, there were two possible escape routes: Melas could fall back on Genoa, which could be supplied by the British Royal Navy, or he could try and slip northward and cross the Po. Once over the river, he could march home or even resume the offensive with a thrust at Milan and French communications.

Bonaparte was certainly human and capable of mistakes, even self-delusion. He now knew Melas was in Alessandria, but Austrian units still were falling back. Melas was abandoning the plain of Scrivia (sometimes called the plain of Marengo). This seemingly trivial fact seemed very significant, since the plain was almost the only one in Italy where masses of cavalry could charge at full speed. The Austrians had superior cavalry forces; if Melas had wanted to fight, why give up this ground?

The Austrian quarry was escaping, or so it seemed to a worried Bonaparte. Melas had to be trapped, cornered, and forced to fight. The First Consul had posted units along the banks of the Po, at Piacenza, Crema, Milan, and Turin, in an effort to “cover all bases” against Austrian moves. Now, he weakened his field army further by dispatching General Desaix toward Rivalta and Novi, with a thought of eventually cutting the road to Genoa. Bonaparte still felt Melas would try to bolt toward the Mediterranean port. Thanks to this delusion, the First Consul violated one of his own precepts of war: Concentrate your forces for a decision in the field.

It continued to rain throughout the 13th, the deluge punctuated by thin veins of lightning and booming claps of thunder. Bonaparte visited the village of Marengo, climbed a tower, and anxiously scanned the western horizon. There, in the distance just beyond the Bormida River, lay Alessandria and the Austrian army. He couldn’t shake his firm conviction that Melas was about to slip the net.

Evening came, and the French settled down to a thoroughly wet, cold, and miserable night. Rations were as sodden as the men’s spirits; Private Coignet of the 96th Demi-Brigade recalled years later how they had to choke down damp and moldy bread. Even the elite Consular Guard was having a rough time of it, the grenadiers soaked to the skin and their feet ankle-deep in glutinous muck.

Bonaparte still thought he had the initiative, but he was living in a dream world, a dream world aided and abetted by sloppy staff work. It was reported that the Austrians had retired beyond the Bormida River, destroying the bridge behind them. This was not true. Bonaparte dispatched a staff officer who not only confirmed the earlier report, but failed to notice the Austrians had built a second pontoon bridge over the waterway. The night had been dark and rainy, but this was a serious lapse.

In fact Melas was going to attack, not retreat. At 71 the old “fox” was not about to be cornered by the French “hounds.” If he retreated to Genoa and the British fleet, he might be trapped by Bonaparte on the one hand and Massena on the other and not reach his destination. A northward escape also held little interest. No, the prey was going to the predator, and Melas was determined to attack.

The Austrian offensive began in the early-morning hours of June 14, 1800. The Battle of Marengo was about to begin, a contest that would not only decide the outcome of the Italian campaign, but also determine Napoleon Bonaparte’s future as ruler of France.

In Marengo, French Awakened by a “Reveille of Gunfire”

The French center rested on Marengo, variously described as a farmstead or village, but generally a cluster of rural stone buildings. The area was generally flat, but on closer inspection some variety was provided by pockets of willow, chestnut, and poplar trees. Other farms dotted the landscape, which favored the defense. Fontanone Creek fronted Marengo, but what was normally a little vein of water was now an engorged artery choked by the recent rains, its banks steep and slippery with mud. Generals Gardanne and Chambarlhac of Victor’s corps held Marengo supported by only five guns.

The sleeping French were rudely awakened by a “reveille of gunfire” and taken by almost complete surprise. Melas marched his army across the Bormida bridges in three columns. General O’Reilly was the first over the river and turned south to form the Austrian right wing. General Melas and his chief of staff General Zack were in the second column of some 18,000 men; they were to form the main attack at Marengo. A third column under General Ott wheeled north to form the Austrian left.

Melas, too, was capable of making mistakes, and made some major errors at Marengo. The third column was particularly strong because Melas thought the French had the bulk of their forces at Castel Ceriolo, an erroneous assumption. He also did not add Alessandria’s large garrison to his field army, which could have boosted his advantage even further. Finally, Melas detached about a third of his cavalry from the center and sent them south because there was information General Suchet’s cavalry was at Acqui. The report was false.

Bonaparte spent the night at Torre di Garofoli, a splendid castle crowned by a campanile, or bell tower. For several hours he refused to believe the Austrian attack was anything but a feint, a smokescreen thrown up to cover their withdrawal. It was at about 10 am that Bonaparte realized his error. Couriers were dispatched to call back scattered units, most particularly to General Desaix.

In the meantime the Battle of Marengo was evolving into a series of seesaw attacks and counterattacks. Momentarily the Austrians would gain the upper hand then the French would counter with a reposte. Bonaparte had about 22–23,000 men under his immediate command, Melas about 33,000. Marengo and the Fontanone stream became a firestorm of shot and shell, with Austrian regiments advancing with bands playing and flags flying. French officers barked commands over the din; musket volleys crashed out in sheets of smoke, flame, and lead; and cannonballs plowed bloody lanes into the packed ranks.

Melas had one hundred guns, the French—depending on what authority you consult—had about 23. Austrian artillery created a terrible havoc; cannonballs were bad enough, but shells spun and sputtered within ranks. When a burning fuse reached the charge, the resulting explosion did terrible execution. Private Coignet, whose 96th Demi-Brigade was part of Victor’s corps engaged at Marengo village, says “a shell burst in the first company, and killed seven men.”

The shot and shell grew so heavy it apparently unnerved Gen. Jacques Chambarlhac. When an orderly was killed nearby, Chambarlhac dug in his spurs and galloped off in panic. Coignet records he disappeared for the rest of the day. When Chambarlhac did show his face after the battle, one of his soldiers fired a shot at him. They could forgive almost anything but cowardice.

Lannes and Murat came up in Victor’s support but the French were still very hard pressed. Bonaparte arrived on the battlefield and saw the right was in extreme danger: If Ott took Castel Ceriolo unopposed, the French flank might be turned and disaster would ensue. He called up his remaining reserves, including the Consular Guard and Monnier’s division. In particular Monnier was to deny Castel Ceriolo to the enemy.

In the center Victor’s division was nearing the end of its rope. Bloodied and exhausted, it had held for the better part of five or six hours. They had begun the battle somewhat bedraggled; now they were muddy and sweat-stained, their lower lips and faces powder-blackened from biting cartridges. By around noon ammunition was almost gone—soon there would be nothing left to fight with but bayonets and clubbed muskets. Luckily there was a pause around noon when the Austrians regrouped for the final push.

The Consular Guard came forward, nine hundred grenadiers and chasseurs with bristling mustaches and tall bearskin caps marching in perfect order. They had left Torre di Garofoli at about 11:30 am, covering the approximately three miles to the battlefield in about an hour and a half. Their first task was to act as couriers, bringing up ammunition to Victor’s decimated corps. Coignet was one of the recipients of these cartridges, and he gratefully recalled that this act “saved our lives.”

Victor’s men doggedly blazed away, but the heavy fighting produced another problem. Coignet remembered “those cursed cartridges could no longer go into our fouled and heated musket barrels.” The muskets were hot from frequent use, and black powder residue was clogging the barrels. The soldiers cooled the barrels and washed away the fowling by the only method they had on hand. Coignet unblushingly reports that “we had to piss into them.”

In the meantime the Consular Guard marched to the French right in support of Lannes’s corps. When Austrian cavalry appeared, officers shouted the command “Cavaliers! Formez la carre!” (Horsemen! Form square!) The four-sided formation was usually proof against cavalry, and once in place the guard coolly poured a hail of musket balls into their attackers.

The Austrian Lobkowitz dragoons were shredded by the musket fire and broke off the attack.

“Courage, Soldiers! The Reserves Are Coming!”

But the guard was in a vulnerable position, and General Ott now ordered artillery and infantry fire to be directed at their square. Cannonballs smashed into the guard and Austrian musket fire peppered the ranks. Within a half hour 260 of the nine hundred men were dead or wounded.

Bonaparte himself was in the thick of the fighting, conspicuous in his gold-braided dark- blue uniform, gray greatcoat, and the black cocked hat that was soon to be his distinctive trademark. At one point he stood on the bank of a ditch, his horse’s bridle in one hand, a riding crop in the other. Suddenly mounting, and disregarding the scores of cannonballs that flew all around, Bonaparte galloped over to nearby troops and shouted “Courage, soldats!! [Courage, soldiers!] The reserves are coming! Stand firm!” The bloodied survivors responded with a hearty “Vive Bonaparte!”

By about 2:30 it was clear the French had lost the Battle of Marengo. The Army of the Reserve was giving way, falling back before superior enemy numbers and a grueling artillery barrage. Flesh and blood could stand no more; in Coignet’s unit, only 14 grenadiers of the original 170 were still standing, the rest being dead or wounded. Coignet himself was badly shaken up when he received a heavy Austrian saber slash that cut off his queue and an epaulet. Stunned by the blow, he fell headlong into a ditch, only to be ridden over by cavalry. When he came to his senses he saved himself by grabbing the tail of a dragoon’s horse as the trooper retreated. Even Coignet freely admitted that the French were “quite ready to give up, but for the encouragement of the officers.”

General Melas was so certain he had achieved a major victory over Bonaparte he assigned the pursuit and “mop-up” duties to a column under his chief of staff General Zack. Melas had had a long, exhausting day, and had been slightly wounded. The Austrian commander in chief felt justified in leaving the field; the French were plainly crushed.

But had he achieved a victory? An exultant shout arose from the battered French ranks, “Here they are! Here they are!” Desaix had arrived in the proverbial nick of time with some five thousand troops. There are several versions of how he managed to come to the rescue. Some hours earlier Bonaparte had sent him an urgent message of recall, the text of which supposedly ran, “I had thought to attack Melas. He attacked me first. For God’s sake come up if you can.” Some say Desaix was within reach because he had been held up by flood waters, others that he was already marching “to the sound of the guns” when Bonaparte’s frantic missive reached him.

Whatever the case, Desaix was there—but was he in time? He galloped up to Bonaparte, his uniform muddy and his horse lathered in sweat, for a quick consultation. Cool as ever, Bonaparte asked, “Well, what do you think of it?” According to most sources Desaix replied, “This battle is completely lost, but it is only two o’clock [some sources say three]; there is time to win another.”

Desaix was as good as his word, leading his men and the shattered remnants of Victor’s corps over to the attack. Victory or defeat hung in the balance as the French smashed into General Zack’s column. Many of these Austrians were grenadiers, men picked for their toughness and resolve, and conquering them would be no small matter. As the French went forward, General Marmont brought up four guns that poured salvo after salvo of case shot into the Austrians, tearing bloody lanes into their ranks with every discharge.

An ammunition wagon exploded, momentarily stunning the Austrians. It was at this precise moment that Gen. François Kellermann led a charge against the Austrian flank. He had only four hundred troopers, but had no hesitation in ordering “Au galop! Chargez!” (At the gallop! Charge!) The French cavalry plunged into the Austrian grenadiers like furies, sabering left and right. Gen. Jean-Baptiste Bessieres, seeing Kellermann’s charge, moved the horse grenadiers and chausseurs of the Consular Guard forward with the command,“Escadrons … en avant … marche!” (Squadrons—forward—march!)

Kellermann’s cavalry charge, coupled with Desaix’s bold advance, proved too much for the Austrians. Defeat was turned into victory as the Austrian right wing collapsed in headlong flight back to Alessandria. General Zack and several thousand troops were taken prisoner, stunned that their apparent triumph had turned to ashes. The Austrians left under General Ott retreated in good order, but no one could deny the French had won an incredible 11th-hour victory over heavy odds. Bonaparte had lost the first Battle of Marengo, only to win a second Battle of Marengo a few hours later.

The fighting died out about 9 pm, allowing the victors to take stock of the situation. The Austrians lost 15 colors, 40 guns, and eight thousand prisoners; a further six thousand were casualties on the field. French casualties were put at some seven thousand. General Desaix was dead, shot and killed almost instantly at the head of his men near Vigna Sancta. Bonaparte was genuinely grief-stricken when he heard the news; he knew how much the fallen general had contributed to the final victory. Indeed, Bonaparte might have toppled from power had he been defeated at Marengo. The whole course of French, and even European, history was effected by Desaix’s timely return. A shocked Melas asked for an armistice, which was granted. Eventually the Second Coalition fell apart, and there was a general—if temporary—peace in Europe by 1802.

Marengo had a curious culinary epilogue, something that keeps its memory forever green. Durnand, Bonaparte’s cook, knew that the First Consul was bound to be famished after the long and hard-fought day. There was little food to be had, so foragers were sent out to scour the countryside. All that they could come up with was a scrawny chicken, four tomatoes, three eggs, a few crayfish, and a little garlic.

Durnand had to improvise, so he cut up the skinny fowl with a saber and fried it in olive oil, garlic, and a splash of cognac. The crayfish were also fried and placed on top of the chicken as a kind of garnish. When Bonaparte ate the dish, he found it so delicious he commanded it be served after every battle, or so the story goes. And thus was born Poulet á la Marengo, Chicken Marengo, an edible commemoration of a great battle.

“…fowled and heated musket barrels.”

Yet despite having “fowled” muskets, the men never chickened out!