By Robert Barr Smith

They came out of the sea, out of the darkness, and they brought death, terror, and destruction with them. Leaving behind towering pyres of oily smoke, they were gone before their foe could react. Every German soldier would hear about these raiders and remember them. They would fear the name Commando.

The Special Service Brigade, formal designation of the Commando forces, attracted quite a collection of daring, aggressive officers, a few of them a bit on the eccentric side, but all ready to take on any job that would get them into the war. An example was Second Lt. Peter Young, a young officer of the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment.

Young rode a motorcycle through vile weather to appear at an interview for the brigade, and by the time he arrived, he “was in a desperate mood and ready to volunteer for anything, particularly if it did not involve motor-bicycles. I was an hour late. The interviewing officer, happily, was two hours late. Eventually, I was ushered into the presence of a captain who bore, I thought, a superficial resemblance to Mr. Pickwick and certainly looked benevolent. This, I said to myself, will be some staff officer from the War Office…. He asked next if I knew anything about small boats; much experience of canoeing on the River Isis justified me in assuring him that my knowledge was extensive. I was in.”

Only later would the youngster realize that the benevolent captain was his commander, Lt. Col. John Durnford-Slater.

Special Service Brigade was a different sort of outfit. Each of its Commandos was stationed in some small town. There was a headquarters, but individual soldiers lived and ate in private homes and received an allowance to cover expenses. In such an elite outfit, there was little need for conventional disciplinary measures: the ultimate, dreaded punishment was RTU, “returned to unit,” banishing a soldier from the Commandos. Once the ranks were filled in 3 Commando, new men entered at the lowest officer or enlisted grade and competed with their comrades for promotion.

“Men of Character Beyond the Normal.”

A good many first-class NCOs gave up their precious stripes to serve as Commandos and won them back by demonstrated excellence in the unit. Among them were characters like Corporal Lofty King of the Rifle Brigade, tall and hard-nosed, very tough on his men. “It’s good for them, Colonel,” he told Durnford-Slater. “It won’t do them any harm.” Lofty King was one of those happy warriors who actually love combat; in action he was a lion, but he was kind to his men. He and his fellows were Durnford-Slater’s kind of men: in the colonel’s words, “men of character beyond the normal.”

Combat training was very tough indeed, almost brutal, with much use of live ammunition. Physical training was equally tough; when the Commandos were not running cross-country with full gear, they were bashing each other on the rugby field. Three Commando was stationed at Largs, on the River Clyde in Scotland. There its men trained in the rocky hills and barren uplands above the river and practiced landing operations on the beaches along the Clyde itself.

Durnford-Slater drove his men hard: Every morning they did 20 to 30 landings, pouring out of landing craft, sprinting for cover with all their gear and weapons. Before they were through, 30 men could exit a landing craft, reach cover 25 yards away, and do it all in 10 seconds. The days began early and did not end until dark; on top of that, the Commandos were out on night operations at least three nights a week.

Billeted in and around the town, the young soldiers of the Commando seem to have gotten on well with most of the local population, a happy relationship that produced more than a few marriages. Occasionally, however, high spirits and too much beer required the intervention of the Commando’s own police force, led by an ex-boxer and ex-cop, Sergeant Bill Chitty. Chitty’s hardcases normally took care of minor disciplinary situations themselves, with what their commanding officer called “a good handling,” to the satisfaction of both their commander and the local police. On one occasion, in fact, Chitty’s heroes took on a whole camp of troublesome imported Irish laborers and whipped the lot, to the intense satisfaction of the local constabulary.

Still, in spite of hard training and simple off-duty pleasures, the men of 3 Commando ached for a chance at the enemy. They were about to get their chance, for in November 1941, 3 Commando’s commanding officer, John Durnford-Slater, was called to London to report to Lord Louis Mountbatten, chief of Combined Operations. Mountbatten asked his young commander a straightforward question: Could 3 Commando successfully raid a town in central Norway defended by a garrison and a battery of guns covering the approaches to the town? They could, said Durnford-Slater, if escorting warships could close in and hammer the battery. “You can rely on our men to look after the German garrison.” Mountbatten nodded, and the show was on.

Adolf Hitler set great store by the German occupation of Norway. He had therefore been furious when the Commandos struck the Norwegian Lofoten Islands in March 1941, inflicting a humiliating defeat on the master race. The Lofotens squatted in the frigid gloom of the North Sea off the Norwegian coast, about due west of Narvik, and on these islands factories produced about 50 percent of Norway’s enormous output of fish oil. This product was used by Germany in vitamin tablets for the Army and to make glycerine, a critical ingredient in the manufacture of explosives. The Lofoten operation—dubbed “Claymore”—aimed to destroy these factories and to hurt the occupying Germans in any other way that seemed good to the raiders.

A Dominating Victory for the Commandos

The darkness of mid-winter was the perfect time for the Lofoten raid, in spite of the bitter cold. Most German aircraft were grounded on the north Norwegian airfields—without ski-landing gear. No plane could take off to interfere with the raid. Armed German trawlers worked the area, but no heavier naval units were reported. And so, when the Commandos appeared out of a murky dawn, they were unopposed. A single German armed trawler was quickly battered into surrender by the destroyer HMS Somali. Most of the German crew died or were wounded. The only British casualty in the whole operation was an embarrassed officer who managed to shoot himself in the leg with his own pistol.

The raiders fired the oil factories, destroyed 11 ships and some 800,000 gallons of oil, and returned to Britain unchallenged, taking with them more than 300 volunteers for the forces of Free Norway. They also took home more than 200 German prisoners, including the head of the local Gestapo, some 60 Quislings (Nazi collaborators), and a captured trawler. And before they left, Durnford-Slater addressed another group of suspected Quislings with some terse and ominous advice for the future: “Yeah, well, I don’t want to hear any more of this bloody Quisling business. It’s no bloody good, I’m telling you. If I hear there’s been any more of it, I’ll be back again and next time I’ll take the whole bloody lot of you. Now clear off!”

To add further insult to the injury inflicted on the Germans, one Lieutenant Wills found the local post office and sent a wire addressed to “A. Hitler, Berlin.” It is worth quoting: “You said your last speech German troops would meet the English wherever they landed stop where are your troops? Wills 2-lieut.”

In September, a British-Canadian force struck isolated Spitzbergen, some 350 icy miles north of the tip of Norway. Again the raiders hit without warning and got away clean. Behind them they left towering fires consuming almost half a million tons of coal and some 275,000 gallons of petroleum products, vital resources Germany would never see. More loyalist Norwegians went home with the raiders. For the master race, there was still more trouble to come.

Operation Archery

For toward the end of October, leadership of British Combined Operations had been taken over by Lord Mountbatten, cousin to the king, a dashing Royal Navy officer of daring, keen intelligence, and great energy. Within two months of assuming command, Mountbatten staged the most damaging raid yet, and mightily got Hitler’s goat in the process.

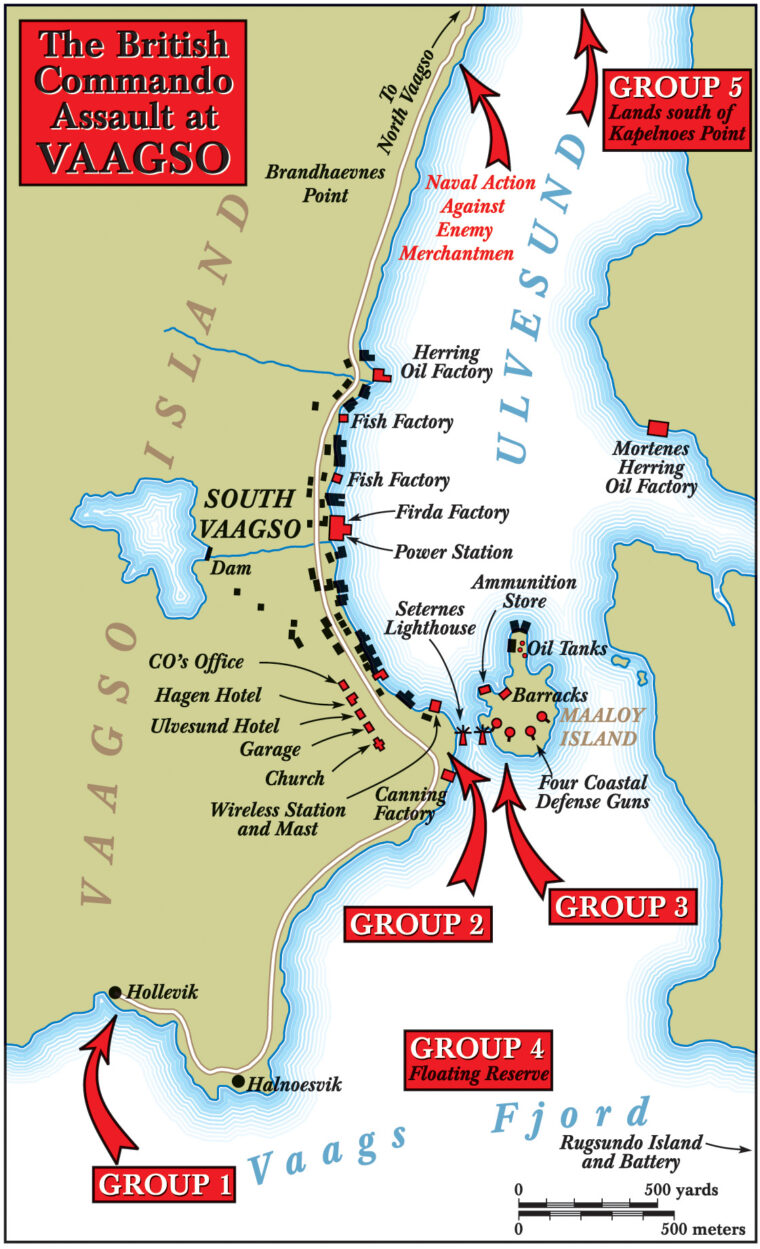

As Durnford-Slater learned to his delight, the target was again Norwegian: the little port of South Vaagso, some 350 miles north of Norway’s southern tip and about halfway between Bergen and Trondheim. Like the Lofotens, this area also produced substantial quantities of vital fish oil for the German war machine. The sheltered waters around the town provided a staging area for German coastal convoys traveling up and down the Indreled, the Inner Passage, sheltered by Norway’s hundreds of offshore islands. Vaagso lies on spectacular Nordfjord, stretching 70 miles deep into the hinterland of Norway. It is ice-free throughout the year, thanks to the waters of the Gulf Stream.

The operation was called “Archery,” and planning and preparation for the raid were painstaking. Combined Operations specialists in London built a detailed model of the Vaagso area, which Durnford-Slater carried back to Scotland in a packing case, in a passenger compartment on the train. Briefings were made from this model, although nobody but the raid’s leaders knew the actual name of the place they were to attack. Successful dress rehearsals were run at the Royal Navy anchorage of Scapa Flow in the far north of Scotland.

Mounting a Small But Elite Strike Force

After the walk-over raids on the Lofotens and Spitzbergen, the Commandos were spoiling for a real fight. This time it appeared they might get one. There were perhaps 240 German troops in and around the town, plus a tank and about 50 sailors. On Maaloy Island, near the town, a four-gun battery of French 125mm guns protected Vaags Fjord, on which the town lay; the Maaloy garrison also manned an anti-aircraft gun, a searchlight, and a couple of machine guns.

There were two more cannon—liberated 130mm Russian field pieces—on the nearby island of Rugsundo, and a battery of mobile 105mm guns protected Ulvesund, the anchorage where German convoys formed up for voyages down the coast. Two torpedo tubes were trained on the entrance to the fjord. Three Luftwaffe bases were within flying distance of Vaagso—Trondheim, Herdla, and Stavanger—capable of launching about four squadrons of fighters and bombers. However, British planners hoped that the perennial dirty weather of the far northern winter might give some measure of cover against German aircraft. In addition, the RAF would do what it could to interdict German aircraft before they could reach the Vaagso area.

The British strike force would number fewer than 600 men, a neat package of 3 Commando, a troop and a half of 2 Commando, Royal Engineers from 6 Commando, medics from 4 Commando, some War Office Intelligence officers, and interpreters of the Royal Norwegian Army. By this time in the war a Commando troop was composed of three officers and, in British terminology, about 60 “other ranks,” soldiers and NCOs. Six of these troops, plus a small headquarters, made up a Commando, the equivalent of a very small battalion.

In overall charge of the operation was Brigadier Charles Haydon, an Irish Guards officer given to careful planning of the most minute details of any operation. The better you planned, Haydon believed and preached, the better the operation went and the fewer casualties you took. He was the sort of commander junior officers adored, careful of his men but willing to let them do their jobs without micro-management. Haydon customarily gave great responsibility to his young leaders, issuing mission-type orders, standing by to help, but otherwise letting his officers get on with the war on their own.

Churchill Carried a Claymore Broadsword and Bagpipes Into Combat

On shore, the landing party would be led by Colonel John Durnford-Slater, still commanding officer of 3 Commando. Durnford-Slater, a gunner, was a 30-year-old captain at the beginning of the war, a veteran of years of service in India. He had volunteered for the Commandos when the force was first raised. Like the other volunteers, he did not know what he was joining, but was eager to leave his adjutant’s job at an artillery training post and get into the war. He was both delighted and startled when his orders arrived, promoting him to lieutenant colonel and directing him to forthwith “raise and command number 3 commando.” Suddenly he was part of the war in a big way.

His executive officer was one of the legitimate characters of an army that abounded in them, Major J.M.T.F. Churchill, MC, known to his friends as Jack. Churchill was a born leader, a ferocious officer who carried a claymore broadsword in combat and roused his own Scots blood by playing on his own bagpipes, a sound not everyone found edifying. Churchill had survived Dunkirk, arriving at the port by bicycle, carrying a longbow with which, legend tells us, he had dispatched at least one German. He would later win the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for the singlehanded capture of some 30 Germans, apparently by appearing suddenly out of the night with a great warlike shout and brandished claymore.

The rest of Durnford-Slater’s officers were unique characters in their own right. Captain John Giles, commanding 3 Troop, was a huge man, a heavyweight boxing champion, worshipped by his men. On one occasion, during training at Largs, he marched his troop off the end of a pier carrying full equipment, then ordered “column right,” swam them back to shore, and marched off. His counterpart in 6 Troop was the inventive Peter Young, now a captain. Mustachioed Captain Algy Forrester commanded 4 Troop. A newspaperman by trade, he had trained as an artilleryman. With no idea of infantry tactics, he had volunteered for the Commandos and learned to be an expert foot soldier in a hurry. One Troop followed Captain Bill Bradley, described as a “tall and rather wild northern Irishman.”

Tip of the Spear

This collection of free spirits, eager for action, included three Irish officers who actually hatched a plan to plant explosives at the German Embassy in Dublin, an effort authorized by Durnford-Slater himself. The officers were sure the embassy was a clearinghouse for information about British convoys, and they felt the building could first be emptied of innocent Irish employees by the judicious offer of good whiskey “and other rewards.” The unit doctor, Irish Captain Sam Corry, had arranged leave to Dublin to check out the target, and supply officer Charley Head was collecting the requisite explosives when the word came down. A new operation had been laid on, and Durnford-Slater’s men were its spearhead.

Rear Admiral Harold Burrough commanded the Royal Navy units involved in the raid. Burrough, an Oxford-educated veteran of the great World War I fight at Jutland, was a career Royal Navy man, a calm, thoughtful officer of great experience. Naval support for the raiders came from HMS Kenya, a 31-knot, 6-inch gun cruiser that would also serve as the headquarters vessel. With Kenya sailed Hunt-class destroyer HMS Chiddingfold and three O-class destroyers, Oribi, Onslow, and Offa. All carried 4-inch armament: two guns for Offa, four for each of the rest. The troops were embarked in infantry assault ships Prince Charles and Prince Leopold, in civilian life excursion ships in the Channel trade. Finally, the submarine HMS Tuna would serve as a navigational beacon, a sure point of reference in the gloom outside the mouth of the fjord.

The RAF, operating at very long range, would furnish such support as it could. Its bases were a long way from the target: Wick, far to the north of Scotland, and Sumburgh in the Shetlands. The nearest base to Vaagso—Sumburgh—was some 250 nautical miles from the target; Wick was about 400 nautical miles away. The Bristol Beaufighters and fighter-model Blenheims of the cover force, and the Hampden and Blenheim bombers would have a long way to fly, a limited time above the objective, and a very long flight home, especially for a damaged aircraft.

29 Prisoners, No Casualties

The infantry attack ships, covered by destroyers, sailed on Christmas Eve, headed into a Force 8 gale for Sollum Voe in the Shetland Islands. Just before they left Scapa Flow, Mountbatten spoke to the raiders. He told the men how proud and confident he was of them and their effort, and he reminded them that when his destroyer, Kelly, had been sunk off Crete, the Luftwaffe had machine-gunned the survivors in the water. “There is,” he said, “no need to treat them gently on my account.”

After a very difficult passage through heavy seas, the little flotilla reached Sollum Voe, and stayed there a day while the storm diminished a little. Prince Charles, helped by Chiddingfold, pumped more than a hundred tons of seawater out of her vitals. Meanwhile, on December 26, Boxing Day, a diversionary force, 12 Commando, was going ashore in the Lofotens to distract the German command from the real objective. During the diversion, 12 Commando would stay on shore two days destroying German installations without suffering casualties and return with 29 prisoners and about 200 eager recruits for the forces of Free Norway.

In the late afternoon of December 26, the main force sailed for Vaagso from Sollum Voe, making a perfect landfall in the deep cold of the early-morning darkness. The captain of Kenya had done a spectacular job of navigation in the night, and he had gotten the flotilla to Vaagso precisely on schedule, even though in these latitudes the winter sun does not rise until about 10 o’clock and the morning sky was clear and spotted with stars. It was 0700, and HMS Tuna was precisely where she was supposed to be, her steady signal heard on Kenya’s asdic before her conning tower came into view in the gloom.

On board the transports, the landing force was ready. They had been called to breakfast at 0500, checked their gear and weapons, and now stood by, ready to board the landing craft that would take them ashore.

Graffiti, Lectures, and Waiting

The task force moved into the mouth of the fjord, cruising slowly, the ships keeping their interval by using the ancient device of the “towing spar,” a white-painted float towed behind each ship. The float left a visible wake behind it, and following vessels had only to keep the float in sight to stay on station.

On shore, the Norwegian inhabitants were up and about the day’s business. Daily life went on, although, with few exceptions, the citizens had no love for their conquerors. Some of the younger men had already fled to England to join the forces of Free Norway, and those who remained behind dreamed of the day when the hated invader was driven out. Patriotic graffiti appeared magically on building walls in Vaagso and other Norwegian towns. When the Germans threatened reprisals against any property on which the slogans appeared, the graffiti began to appear only on the walls of structures owned by collaborators.

This chilly morning, yawning German soldiers were turning out to go to their duty stations. Over on Maaloy Island the crews of the four coastal defense guns were having breakfast; the business of the morning for them was the dreary monthly lecture on military courtesy, doubtless as boring to these men as such lectures are to soldiers the world over.

As the invasion fleet moved into the tight waters of the fjord, sailing in darkness between steep, snow-covered hills on either side, the Royal Navy broke out its battle ensigns, enormous flags much larger than the normal White Ensign. Watertight doors were dogged shut, and buckets appeared in compartments thereby cut off from the latrines. It was pitch dark, for the first faint light would not come until a little before 9. The attack ships dropped anchor in a little bay out of the line of fire of the Maaloy Island batteries. The landing craft, American Higgins boats, would move from there down the coast and around a projecting point of land before running in for the landing beaches.

The German garrison was both ready and unready. By coincidence, troops in South Vaagso were engaged in working on their positions, and thus already almost in a defensive posture. However, when a sentry manning a German observation post reported what appeared to be warships moving down the fjord, he was told it was probably a German convoy. When he insisted, the man on the other end of the telephone suggested the observer might have been celebrating Christmas a little too enthusiastically. The OP soldier persisted, however, and alerted the German Navy command of his sighting. Instead of telling the nearest Army officer of the report, the man on the other end of the telephone, a sailor, found a boat and rowed off to tell his naval superior.

Attack on the Oil Factory

Even then German reactions were slow: they were only finally alerted when shells from Kenya’s 12 6-inch guns began to scream into the German barracks area on Maaloy, some 400 or 500 shells in less than 10 minutes. Offa and Onslow’s 4-inchers joined in, and the German troops dove into their trenches and bunkers. Out in the fjord the British landing craft headed for shore.

Just before 9 am, RAF Hampdens roared in from the sea. Hampdens, twin-engine bombers with long, skinny, tubelike fuselages, were surely among the most peculiar looking aircraft of any war, but they bored in to carry out their mission, to dump smoke bombs on the selected landing sites covering the landing of Durnford-Slater’s men. At Maaloy Island, standing in the bow of his boat, Major Jack Churchill played his Group 3 ashore with the “March of the Cameron Men” on his bagpipes. Churchill led 105 men, 5 and 6 Troops, against Maaloy Island. Their objective was the big Mortense herring oil factory, the shore batteries, an antiaircraft position, and any German troops they might encounter.

Lieutenant R. Clement’s Group 1 had the mission to carry the village of Hollevik, then form the onshore reserve. Durnford-Slater would lead Group 2, about 200 men of 1, 2, 3, and 4 Troops, against Vaagso itself, while Captain D. Birney’s 30 men of Group 5 blocked the road south into Vaagso from Rodberg. Group 4, Captain R.H. Hooper’s 65 troopers, would remain as a floating reserve in Kenya. Clement carried out the first part of his mission easily, then moved north up the edge of the fjord toward Vaagso.

A Tragically Errant Bomb

Durnford-Slater was in the lead Higgins boat, 10 Verey pistols laid out beside him. Ten flares were the signal for the Navy to cease its bombardment, and Durnford-Slater had made the intelligent decision to avoid the delay caused by reloading a single pistol. In the event, he got no further than his third Verey light before Kenya and the destroyers ceased fire. The main force closed the shoreline as planned, at the foot of a sheer rocky cliff, so unlikely a landing place that it was not covered by German defenses.

However, Durnford-Slater’s men encountered tragedy even before they stepped on shore: not German fire, but an RAF phosphorus smoke bomb from a Hampden hit by flak from the German armed trawler Foehn. At least half a Commando troop was either killed or burned by the bomb. Lieutenant Arthur Komrower, trapped against a flaming landing craft, was pulled from the frigid water by Captain Martin Linge, a tough Norwegian intelligence officer who had been a well-known actor before the war.

A line of Commandos quickly offloaded the landing craft of much of its ammunition and pushed it away from shore, out into the current to sink. Doctor Corry turned to treating the terribly burned survivors of the blazing Higgins boat.

The rest of Durnford-Slater’s men surged ashore and went straight into action against German infantry in the town. Vaagso was a long, skinny settlement, about three quarters of a mile of unpainted wooden buildings stretched out along the shoreline road, with the cliffs not far behind them. Clearing the town meant fighting house to house for much of the length of the village.

German resistance was determined, especially from one large building they had made into a strongpoint. And it was ferocious. It developed that some 50 men of a first-class German regiment had spent Christmas in the town and were still there. Captain Johnny Giles led a wild charge to carry the strongpoint, crashing through the front door, tossing grenades into each of the rooms, and chasing the German survivors through the back door. Giles was mortally wounded at that door, shot down by a wounded German, but the strongpoint remained British. His brother down and dying, Lieutenant Bruce Giles took command.

The Decimation of Commando Leadership and a Resourceful Comeback

Along the waterfront, Captain Algy Forester led what was left of the troop decimated by the errant bomb, firing his Thompson submachine gun from the hip and throwing grenades into the houses as he passed. Komrower was in the thick of the fighting as well, even though he was hobbling badly, helping himself along with a stick used as a cane.

The Germans fell back into the Ulvesund Hotel, and the British twice attempted to storm the building under heavy fire. Forester got as far as the hotel door, an armed grenade in his hand. A German bullet slammed into his chest, and he fell on his own grenade as it detonated. Norwegian Captain Linge took command when all the British officers were down, led another charge, and in his turn died at the hotel door.

Other officers were dead or wounded, depriving the Commandos of many of their leaders. A veteran corporal called Knocker White took charge of the handful of men around him, and the Commandos prepared again to storm the Ulvesund Hotel, packed with German defenders. At this juncture, Captain Bill Bradley appeared with a 3-inch mortar. The weapon was not official. Bradley had obtained it and its ammunition on his own. Such were the tough and resourceful characters who wore the Commando flash.

Now his Sergeant Ramsey got the weapon into action. The tube was pointed almost straight up to fire at minimum range, and his amateur gunners put their first round down the hotel chimney, causing many casualties and setting the place afire. As the mortar continued to drop shells on the blazing hotel, Knocker White, a handful of Commandos, and a few Norwegian soldiers carried the place with grenades and gunfire. White would earn a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his leadership and courage this day.

The fighting in the streets was confused and vicious. A Reuters correspondent accompanying the Commandos wrote afterward: “Many Germans were roasted to death in homes they made strongpoints and from which they doggedly refused to emerge, even when grenades or a fusillade of shots had set the rooms about them on fire … Norwegian men, women and children, anxious to go to England, were running back to our barges, some in tears, some laughing, all rather scared…. Heavy gunfire reverberated down the fjord to add to the clamour of explosions and the heat of battle.”

During the battle for the hotel, two Commandos, Trooper Dowling and Sergeant Cork, went hunting for the solitary tank known to be part of the German defense force. It was still in its garage next to the hotel. Apparently the crew had been caught in the first attack and killed or scattered. Sergeant Cork laid plenty of demolition charges to make sure of his quarry, then lit his fuses as Dowling crawled out the garage door. The ensuing thunderous explosion destroyed the tank, but a piece of debris struck and killed Sergeant Cork before he could get clear.

”They Appeared to be Enjoying Themselves…”

As the fighting in Vaagso got heavier and heavier, Durnford-Slater called for help. Brigadier Haydon immediately committed the floating reserve under Captain R.H. Hooper. He also called on Mad Jack Churchill, who had by now finished most of his task on the island of Maaloy. Sword in hand, Major Churchill had led his men across the island, overrunning the four guns of the German shore battery and capturing most of the garrison … along with a pair of resident “comfort women,” one Norwegian, the other Belgian.

There had been no substantial organized resistance to Churchill’s rapid advance. The German commander was captured along with some 15 of his men, and other prisoners were collected in ones and twos; those men of the island garrison who tried to fight, died quickly. One tried to disarm Peter Young. Young lived on; the German did not. One horribly wounded German soldier, writhing in agony, was put out of his misery by a British bullet. With German resistance destroyed, one of Churchill’s officers blew up the German coastal defense guns and a dump of mines, while a second officer crossed the sound to set fire to the Mortense herring oil factory.

Churchill sent Captain Young over to help out the main force in Vaagso. Young and 18 men joined up with fiery Lieutenant Denis O’Flaherty, who was leading his men in point-blank fighting through the town. One of Young’s men wrote later: “Our Captain [Young] led the attack here, and although it was slow as we had to go from house to house, we were able to spot and shoot the snipers who were doing the damage…. One of our sergeants received three shots in the back from a sniper who had let us pass. We opened fire on this sniper’s window and settled him. We dashed to the next house…. We threw in petrol, set fire to it and went on our way, leaving one man to deal with the Hun when he eventually appeared.”

Durnford-Slater watched Young and Sergeant George Herbert grenading their way down the main street of Vaagso. “They appeared,” the colonel wrote later, “to be enjoying themselves.”

Now, reinforced by Hooper’s men of the floating reserve, Durnford-Slater’s force began to clear the rest of the town. The fighting was especially fierce for the building the British called the Red Warehouse. O’Flaherty, Peter Young, and a soldier named Sherington rushed the building, where both Sherington and O’Flaherty were badly wounded. The British finally set fire to the warehouse, flushing the remaining defenders out into the fire of a Bren gun. Peter Young led his men on deeper into the town.

Discovering a Valuable German Artifact

Meanwhile, Luftwaffe fighters swept in to attack, and the RAF aircraft and the antiaircraft guns of the Royal Navy struck back. The hills sent back the booming echo of heavy fire from the guns of Kenya and her destroyers, the hammer of AA from the ships, and the roar of automatic weapons, rifles, and grenades from Vaagso itself. As the Navy fought off German air attacks, the warships were also dealing with German shipping. The armed trawler Foehn, battered by the destroyers’ guns, ran aground, as did two small cargo ships. Another merchantman was sunk by Onslow.

The British boarded Foehn to find that her crew had abandoned her and that her captain, Leutnant zur See Lohr, had been killed by shellfire before he could throw overboard his ship’s lead-weighted code books. The books, taken off by Lt. Cmdr. de Costabadie, DSC, one of Mountbatten’s staff, turned out to be a gold mine. They contained a wealth of signs, countersigns, and code words, and the radio call-signs of every German vessel in northern Europe. At about 10 am, Oribi and Onslow destroyed the armed tug Rechtenfleth and freighter Anita L.J. Russ, both of which sailed down Ulvesund unsuspecting. A little after noon, Chiddingfold and Offa sank an armed trawler and the merchantman Anhalt near the mouth of the sound.

German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters shot down several Blenheims but were unable to interfere decisively with the British landing. Onslow disintegrated one German aircraft with a single round from an ancient 4-inch gun fitted on the destroyer more on hope than faith as additional antiaircraft armament. Toward the end of the action, three Heinkel He-111 bombers and two Me-109s appeared over the fjord. RAF Beaufighters promptly knocked two of the Heinkels down, and the survivors left in haste.

The Luftwaffe was less strong than it might have been, for around noon a flight of Blenheims had attacked Herdla airstrip with 250-pound bombs. The RAF lost two aircraft to flak, but their bombs cratered the wooden runway so badly that no aircraft could take off or land. The damage to the strip also took Stavanger airfield’s aircraft out of the action, for they could not fly to Vaagso and return without refueling at Herdla on the way.

Rejection of Surrender

Beyond the cleared Red Warehouse in the streets of Vaagso, the British went on, methodically grenading their way from building to building. Enthusiastic Norwegian civilians carried sacks of grenades from the waterfront to the Commando attack parties in the flaming streets. Leading from the front, Durnford-Slater narrowly escaped death when a German sailor threw a stick grenade at him. The colonel dove for cover, but both soldiers with him were badly wounded.

The German attempted to surrender at that point, but Sergeant Mills, an enormous boxer who guarded the colonel, was having none of it. While the British took prisoners and treated them well, even the tolerant British soldier could not stomach an enemy who tried to kill and then instantly surrendered. Mills advanced toward the German with his rifle raised, and the sailor cried out “Nein, nein!”

“Ja, ja,” replied the sergeant, and squeezed his trigger. Durnford-Slater only mildly reprimanded his pugnacious NCO. “Yeah, well, Mills, you shouldn’t have done that.” And both men went on with the war.

By noon the fighting came to an end with the destruction of a fiercely defended building by Sergeant Ramsey’s deadly mortar, and the firing died away to a spiteful popping of scattered shots. A little before 2 o’clock, as the arctic winter night settled like a shroud over Vaagso and the fjord, Durnford-Slater ordered his men back to the boats. The mission had been accomplished, and it was high time to go. The wounded were carefully loaded aboard, and before 3 pm the raiding party was back on board and headed for the open sea.

On the way to the boats the British commander was profoundly impressed by the action of a dying German, whom several Commandos were trying vainly to help. As Durnford-Slater passed, the German beckoned to him, and the two enemies shook hands in the midst of the smoke and turmoil of war.

Meager Losses; Massive Damage

Behind the British boats, heading back to re-embark, great towering pillars of smoke fouled the sky. Around them, falling like snow from the sky, fluttered thousands of sardine can labels from a destroyed warehouse. The Navy had sunk 10 vessels, 18,000 tons of shipping, and the Commandos had burned or blown up four oil factories and a number of warehouses, fuel tanks, vehicles, the Seternes lighthouse, the telephone exchanges, the steamship wharf, and the German barracks. The Commandos had used 300 pounds of plastic explosive, 150 incendiary bombs, 1,100 pounds of gun cotton, and 150 pounds of ammonal. The results were spectacular.

The Maaloy coastal defense batteries were destroyed along with the garrison’s only tank, and much of the garrison had been killed, wounded, or captured. Between 110 and 130 Germans were dead, without counting the crews of the eight ships destroyed. Another 98 were prisoners of war. Of the Norwegian population, one was killed and five wounded; 70 more happily returned to England to volunteer for the forces of Free Norway. The two comfort women were held on board Kenya under the guard of two delighted British sailors. “Jerry floozies,” explained one of the guards. “Yer can’t keep ’em down.” Apparently you could, however, for the story goes that at a later time the only sign of the two sailor sentries was their rifles leaning outside the ladies’ cabin door … but that is another tale.

The raiders had lost 20 dead, 53 wounded, and no prisoners at all. Three of the dead, including Captain Linge, were Norwegian. The death toll included four mortally wounded men who had died after they had been carried back aboard ship. They were buried at sea, and with them the gallant Captain Giles, whose devoted men would not leave his body behind in the flaming town. Kenya had been hit by a single shell from one of the shore batteries; Oribi had several minor casualties; and the RAF had lost eight aircraft with their crews.

On December 30, the Germans staged a military funeral for the 11 dead of the landing force whose bodies had been left behind. Four days later, the Germans also formally interred the remains of Captain Linge, found in the wreckage of the building he had tried to storm, and those of a British sailor recovered from the landing craft set afire by the errant British smoke bomb.

At first, the Germans were going to burn the house of any Norwegian who had fled to England, but a local Norwegian official intervened and got the burning order rescinded.

A Mighty Blow to the Confidence of the Nazi War Machine

For what amounted to negligible losses, the British had struck a startling blow at a confident Nazi Germany, a blow to German arrogance and self-assurance far out of proportion to the actual losses inflicted on the Germans. Close to the sea, at least, no German soldier would sleep as well after Vaagso as he had before. And the consequences ran far deeper than that. For reasons best recognized by his own twisted view of the world, Hitler considered Norway “the zone of destiny in this war.” News of the Vaagso raid both infuriated and alarmed him, and the consequences were enormous. “If the British go about things properly,” the Führer said, “they will attack northern Norway at several points. By means of an all-out attack by their fleet and ground troops they will try to displace us there, take Narvik if possible, and thus exert pressure on Sweden and Finland. This might be of decisive importance for the outcome of the war.”

Now, Sweden was the vital source of iron ore for the Nazi war machine, and Finland was an ally in the war against Russia. Moreover, Finland and northern Norway provided bases from which to strike at British convoys hauling north through the murderous cold of the Barents Sea to the Russian ports of Murmansk and Archangel. Hitler could not know that the British had no intention of indulging in any fanciful scheme that involved putting ground troops ashore for a long-term expedition in northern Norway. As is common with tyrants, what he did not understand, he feared.

At Hitler’s command the German Navy moved its major fleet units north into Norwegian waters: super-battleship Tirpitz, battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gniesenau, pocket battleship Luetzow, heavy cruisers Hipper and Prinz Eugen, all were sent north, and most of them stayed there. If in their Norwegian bases they posed a major threat to the convoys to Russia, they were at least where the Royal Navy could watch them and stand a better chance of keeping them out of the North Atlantic sea lanes.

Pulling the Wool Over Hitler’s Eyes

In February, Hitler sent Generalfeldmarschall Siegmund List to Norway to size up the defensive situation. List returned with a series of recommendations, and Col. Gen. Rainer von Falkenhorst, commanding in Norway, fell heir to an enormous influx of resources. He not only received 12,000 reinforcements he had earlier requested, but he got another 18,000 men organized into “fortress battalions.” Also forthcoming were new German coastal defense guns to replace the Russian and Belgian ordnance used before the Vaagso raid. By early 1942, three more divisional commands were set up in Norway, and more coastal artillery was delivered. By the time of D-day in 1944, the German garrison in Norway had swollen to an astonishing size, almost 400,000 men.

When the Allies struck in France, these 400,000, with all their weaponry, were far away from the point of decision, unable to influence in any way the outcome of the critical battle for Normandy.

They might as well have been on the moon.

Do you know the names of those who were buried at sea as one of the could be a relative of mine, Gunner Bernard William Wharton 909229?