By Mike Phifer

“Where the hell have you been?”

Major Bert Kennedy, acting commander of Canada’s Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade, asked Lieutenant Farley Mowat of the intelligence section. It was December 5, 1943, and Kennedy was in a foul mood. He had been ordered to launch a diversionary attack across the Moro River without artillery support and establish a stronghold on the north ridgeline. This would be the right flank of Maj. Gen. Christopher Vokes’ 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s attempt to cross the river in its drive for Ortona three miles to the north. “We’re to cross the Moro River right away,” said Kennedy. “No preparation. No support. What’ve you found?”

Mowat, who had been scouting the terrain with an intelligence officer of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, told Kennedy that there was nothing to be seen from the vantage point of the Canadian position on the south bank of the Moro. This did not improve Kennedy’s mood. Kennedy ordered Mowat to take a few scouts and search for a usable crossing. He also ordered Mowat to report back in an hour.

Slipping down to the river with three men under the cover of darkness, Mowat and his scouts waded along the flooded banks of the Moro and eventually found a crossing. They quickly headed back to their lines where they discovered Company A of the Hasty Ps, as the regiment was known, preparing for action. While Mowat reported to Kennedy, scout leader Lieutenant George Langstaff guided the company down to the ford. Once Company A had established a foothold across the river, it would be reinforced with the rest of the battalion.

“Stitching the Darkness” With Tracers

Shortly after 10 pm, Mowat, who was with Kennedy at the time, saw six or seven German machine-gun positions begin, in Mowat’s words, “stitching the darkness with vicious needles of tracers.” Green and white flares burst overhead and soon mortar rounds came crashing down on Company A. Both soldiers “were appalled by the ferocity of the German reaction,” wrote Mowat. Kennedy requested a situation report by radio.

The men of Company A did not get the message. Caught in a wicked crossfire, the company and platoon commanders knew they had to withdraw from a potential death trap. When Kennedy received a report from the company commander the following day, he ordered artillery support to silence the German machine guns covering the ford. Meanwhile, at two points farther upriver more Canadians were attempting to cross the Moro in preparation for an attack on Ortona. They were having a better go of it at one of the points. A bloody December lay ahead for the Canucks.

The Allied advance up the Italian boot toward Rome had begun in early September 1943. The Germans had brought an abrupt halt to the Allied advance at the Gustav and Bernhard fortified lines roughly 90 miles south of the Allied objective. The advance of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army up the western coast of Italy had stalled due to bad weather, fierce German resistance, and heavy casualties.

To get things moving, Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery was to attack with his Eighth Army in eastern Italy. The Eighth Army would cross the Sangro River and advance on the coastal town of Pescara. From there it would swing west to Avezzano. The Allied leadership believed this would threaten Rome and force the Germans to shift troops facing Clark to meet them. At that point, Clark would break through the Gustav Line and link up with Allied units landing at Anzio about 30 miles southwest of Rome. The Italian capital would then fall.

Heavy Rains Slow Montgomery’s Advance

It was a bold plan with the Eighth Army planning to push west to Avezzano by December 25. “I must have fine weather,” said Montgomery, but he would not get it. By mid-November, heavy rains began to fall. Nevertheless, the Eighth Army’s V Corps under Lt. Gen. Charles Allfrey managed to cross the Sangro River in late November.

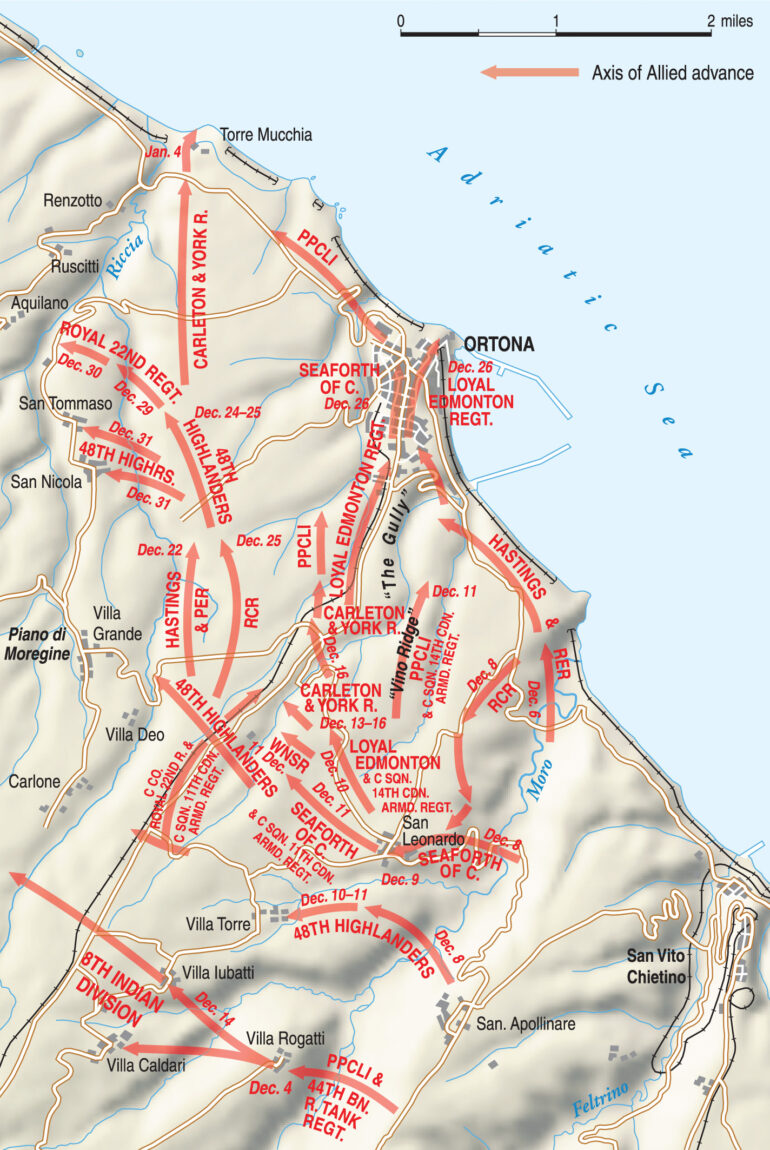

At that point, the Germans counterattacked, which blunted Montgomery’s advance. A bloody engagement ensued in which the V Corps managed to force the Germans back across the Moro River. German engineers began fortifying the ridge on the north side of the river valley. On December 1, the 1st Canadian Division was ordered to take over for the battle-weary British 78th Division on the south side of the river.

Vokes quickly got his troops moving toward the Moro River. By December 3, the majority of the 1st Canadian Division was assembling south of the the 78th Division’s position. A day later the Canadians began taking over for the 78th Division. That same day the Sangro River rose more than six feet. The rising waters washed away the vital pontoon bridge across the waterway. The men of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade, which had not yet reached the 1st Division’s position, found themselves stranded on the south side of the Sangro.

With heavy rains falling and a sea of mud expanding, it became clear to Montgomery that Rome would not be captured anytime soon. Instead, he focused on taking Pescara, which lay 25 miles to the north. At the same time, he had his eyes on Ortona, which was a key deepwater port with a rail line. The Germans had destroyed Ortona’s harbor and railway tracks, but they could be repaired. With the Eighth Army’s supply line stretched to the breaking point, the capture of Ortona became of strategic importance to Montgomery.

Vokes wanted to get all of his units across the flooded Moro as soon as possible, but this would not be easy with the constant rain. On the ridgeline behind the Moro River, General-leutnant Karl Hans Lungershausen’s 90th Panzer Grenadier Division had dug in on the reverse slopes of gullies and ravines dotted with olive groves and vineyards. The Germans had sewed mines in the fields and set up machinegun positions to check the Canadian advance.

Canadian patrols found three potential spots across the river where bridges could be built. One was on a new coast road on the right flank, another was on the old highway that wound through the Moro valley toward the village of the San Leonardo on the German side of the river valley, and a third was a couple of miles upriver from San Leonardo at the small village of Villa Rogatti located on a ridge. Vokes decided he would cross the river at all three points. His troops would attack at night without artillery support, relying primarily on surprise.

Company D Finally Penetrates

With Company A of the Hasty Ps being driven back across the river after its failed attempt at crossing, things were not going well farther upriver at San Leonardo either. At midnight, Company B of the 2nd Brigade’s Seaforth Highlanders set off to cross the river for the village. It would be followed shortly afterward by Companies A and C in preparation for the main attack. The Royal Canadian Engineers stood nearby, waiting to construct a crossing of steel cribs to allow the 17-pounder antitank guns to get across the river to help repulse German counterattacks. Once the Seaforths had established a bridgehead, the engineers planned to construct a Bailey bridge to allow tanks to get across the river.

Companies A and C soon found themselves under heavy German machine-gun fire, which forced Company A back across the river while Company C held on to a small piece of real estate 100 yards from the edge of the Moro. Meanwhile, Company B managed to reach its objective and waited for dawn to arrive.

On the left flank, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Regiment (PPCLI), also of the 2nd Brigade, had better luck when three companies slipped across the Moro and captured Villa Rogatti. Although driven out of the town, the Germans still held fortified positions on the outskirts of Rogatti.

At 9 am, the 200th Regiment of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division counterattacked. Incoming mortar rounds and machine-gun fire hammered the Canadians. The Canucks hung on to Villa Rogatti in expectation of armored support from the British 44th Tank Regiment. German panzer grenadiers charged through olive groves backed by Panzer Mark IV tanks and attacked the village. The Canadians managed to hold on until British tanks arrived to help them repulse the German attack. A second German attack in the afternoon was halted after two hours of hard fighting.

On the Canadian right flank, the Hasty Ps attacked again across the Moro. This time a 20-minute barrage hammered the German positions before Company C crossed the river at 2 pm, followed by Company D. The two companies soon found themselves pinned down by heavy enemy fire. Kennedy ordered the withdrawal of the two companies at 3:40 pm, but Company D was unable to break off.

Unable to make radio contact with Company D, Kennedy figured they had been overrun. Smoke and fog, which had obscured the battlefield, eventually cleared enough for Kennedy to see that Company D had managed to penetrate the German position. He sent Companies A and B to their aid, as well as a platoon of infantry from the Bren gun carriers, who were ordered to dismount and attack on foot.

The Canadians managed to capture the ridge on the north side of the river and quickly dug in on the reverse slope. This gave them a toehold on the German side of the Moro. They braced themselves for the expected German counterattack. Meanwhile, near San Leonardo, the Seaforth Highlanders were unable to capture the village despite the aggressiveness of Company B holding out on the German side of the river. A plan to capture the village was cancelled when British tanks, unable to cross the river, found themselves in a duel with German tanks on the other side of the Moro.

At the division’s headquarters, Vokes was informed by his engineers on the night of December 6 that a bridge could not be built at Villa Rogatti due to terrain factors. By default, San Leonardo was the only place one could be built. While Vokes prepared for a new assault, the Hasty Ps continued to strengthen their toehold. Despite heavy rains and German shelling, the troops managed to manhandle two antitank guns and ammunition across the river and up the muddy ridge. The German counterattack the night of December 7 fell on the Hasty Ps, who managed to repulse the enemy.

The Highlanders Splash Across the Moro River

On December 8, Canadian, British, and Indian batteries hammered the German positions starting at 3:30 pm. Their direct fire was supplemented with aerial bombardment and naval gun fire. When the guns fell silent an hour later, the Canucks attacked. Vokes’ plan called for the 48th Highlanders of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade to attack the 361st Regiment of 90th Panzer Division west of San Leonardo on the escarpment. At the same time, the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR), also of the 1st Brigade, would pass through the Hasty Ps’ bridgehead and attack the village from the right.

The men of the 48th Highlanders splashed across the Moro River and quickly secured their objectives. The rest of the Highlanders came up, dug in, and awaited the German counterattack. But the RCR, which went into action on the right of the 48th Highlanders, was having a tough time. The infantry managed to get about halfway to San Leonardo when heavy German shelling and an armored counterattack stopped them cold. Lt. Col. Daniel Spry, commander of the RCR, ordered his men to dig in and called down artillery fire around the perimeter of his position. The German tanks pulled back, and the Canadians shifted to a place they dubbed Slaughterhouse Hill.

At 10 pm the engineers began building a floating bridge across the river at San Leonardo so tanks could reach the far bank. Enduring enemy fire, the engineers had the bridge completed by 6 am on December 9. Originally, Vokes had planned for the Seaforth Highlanders and the 14th Armoured Regiment, better known as the Calgary Tanks, to jump off from San Leonardo and attack toward the Orsogna-Ortona road. With the RCR unable to reach San Leonardo, the Seaforths and Calgary Tanks would have to take it first.

Major Ned Amy, commander of Squadron A of the Calgary Tanks, set out with 12 tanks to take the village. The men of Company D of the Seaforths rode into battle atop the tanks. Two tanks were lost when they failed to make a sharp turn on the road down to the Moro and rolled over a 30-foot cliff. Once across the river, the infantry dismounted as they came under German machine-gun fire.

A platoon led by Lieutenant John McLean rushed into the village and began to root out the Germans in house-to-house fighting. McLean killed or captured 26 German infantrymen in the process of neutralizing 10 enemy machine guns. The Germans counterattacked with 12 tanks and infantry through the olive groves but were thrown back by Squadron A of the Calgary Tanks, which by then was down to four tanks. San Leonardo was finally in Canadian hands.

Holding “Sterlin Castle”

Besides attacking San Leonardo, the Germans attacked the Hasty Ps and the RCR. The latter held a two-story stone house, which its men had nicknamed “Sterlin Castle” after Lieutenant Mitch Sterlin, who commanded Number 16 Platoon of Company D. In anticipation of the German counterattack, Spry ordered Company A and Sterlin’s platoon to fall back from Slaughterhouse Hill, but neither Lieutenant Jimmy Quayle’s Number 8 Platoon or Sterlin’s platoon received the message.

Quayle, who was positioned to the right of the stone house with his men, soon discovered that the rest of the company had fallen back. He tried to warn Sterlin. Believing that Sterlin’s platoon had been wiped out, Quayle withdrew. But Sterlin and his men were still alive, albeit cut off.

Panzer grenadiers assaulted Sterlin’s position. Through the rifle and machine-gun fire, a small number of German soldiers managed to reach the building and attempted to fire through its windows and doors. They were all killed. When the panzer grenadiers eventually retreated, they left a large number of dead and wounded sprawled around Sterlin Castle.

After the German counterattacks failed to dislodge the Canadian bridgehead, elements of the badly battered German 90th Division realized their defenses at the Moro River had been breached. As a result, they withdrew during the night of December 9 to a strong position less than a mile south of Ortona in front of the Orsogna-Ortona road. There the Germans dug gun pits and shelters in the side of a 200-foot gully that ran for about three miles to the Adriatic Sea. The Canadians respectfully called the strong position “The Gully” during and after the battle. The same night, the 3rd Regiment of General-leutnant Richard Heidrich’s 1st Parachute Division headed south from the Adriatic Line to replace them. More elements of this tough division would follow. The Germans were determined to deny Ortona to the Canadians.

By that time in firm control of the north bank of the Moro River, the Canadians continued their advance toward the Orsogna-Ortona road. At 9 am on December 10, the Loyal Edmonton Regiment of the 2nd Canadian Brigade, backed by the Calgary Tanks, set out to capture a crossroads where old Highway 16 intersected with the Orsogna-Ortona road. The Canadians had codenamed the crossroads Cider. Once Cider was captured, the PPCLI could secure the vine-covered south side of The Gully known as Vino Ridge.

Assault on the Gully

Things started off well enough. The Loyal Edmontons sent word at 1:30 pm that three companies had reached Cider. The problem was that the Loyal Edmontons were not near their objective, a fact recognized by Lt. Col. Cam Ware, the PPCLI’s commander. Despite his protests that his men would be shot to pieces by the enemy holding the high ground around Cider, he was ordered to attack Vino Ridge. As predicted, the PPCLI was hit hard by the Germans in a vicious heavy barrage and counterattack. Ware called off the attack but not before the Germans had wounded three of the regiment’s company commanders.

The tactical significance of The Gully in blocking his approach to Ortona was now clear to Vokes. He ordered his 2nd Brigade to continue their frontal attacks on December 11. The Edmontons kicked off the attack by first attempting to fight their way to Cider. Murderous machine-gun and mortar fire halted the attack. The PPCLI struggled through the vineyards and olive groves of Vino Ridge, which was laced with mines and booby traps. By mid-afternoon the troops had managed to fight their way to the edge of The Gully where the two sides flung grenades at one another. The Seaforths were unable to reach their objective, which was a key ridge overlooking The Gully and Casa Berardi, a three-story house located about three quarters of a mile southwest of Cider.

Despite the efforts of the 2nd Brigade, The Gully was still firmly in German hands. Vokes ordered in his reserves, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade, which had been stranded on the south of the Sangro River. With the river again bridged, the West Nova Scotia Regiment of the 3rd Brigade was ordered to pass through the Seaforths, cross The Gully, and take Casa Berardi.

At 6 pm the West Novas attacked. They took a severe pounding from German artillery and mortar fire as they pushed forward in the mud and darkness. When they approached the edge of The Gully, the Canadians came under heavy small arms fire and could do nothing but dig in and wait until morning. Lt. Col. Pat Bogert, commander of the West Novas, requested artillery support for his morning attack since tanks were unable to traverse the mud. At 7:30 am a reference-coordination barrage mistakenly fell on the West Novas’ position, causing many casualties. This was followed by German artillery fire and an attack by German panzer grenadiers. The Germans were repulsed, and two companies of the West Novas climbed out of their slit trenches and pursued them into The Gully where they were forced to halt by enemy machine-gun and tank fire. The survivors retreated back to their slit trenches. Bogert was among the wounded.

Vokes ordered another assault on The Gully. The Carleton and York Regiment of the 3rd Brigade was to conduct the attack with the support of the Calgary Tanks. At 6 am on December 13, the Canadians attacked in the wake of an artillery barrage. The Canadians captured three machine-gun nests and more than 21 prisoners. Heavy German fire stalled the attack, forcing the Canadians backwith heavy casualties.

Although the main assault failed, probing attacks by the West Novas, Seaforths, and Ontario Tanks fared better. The Canadians found the Germans vulnerable at Casa Berardi, which was at that point seen as the key to capturing The Gully. Vokes ordered the Royal 22nd Regiment of the 3rd Brigade to attack in the morning. Unbeknown to the Canadians, the tired and decimated 90th Panzer Division was being pulled out of the line and replaced with the 1st Parachute Division.

“There Is Only One Safe Place—That Is On the Objective”

At 6:30 am on December 14, a heavy Canadian artillery barrage began pounding the Germans. The Royal 22nd Regiment was ordered to launch an attack on a two-company front. Captain Paul Triquet’s Company C of the regiment was to lead the attack on the left, and Captain Ovila Garceau’s Company D of the regiment was to lead the attack on the right. Major Herschell Smith’s C Squadron of the Ontario Tanks, which had seven tanks, was to support Triquet, whose company was expected to experience greater resistance. At 7:10 am, the two companies advanced into the teeth of German machine-gun, mortar, and tank fire.

A Panzer Mark IV, which had been concealed behind a house, rolled into the open and blasted the Canadians. With Smith’s tanks mired in the mud, the Canadian infantry had to take immediate action to knock out the German tank. Sergeant J.P. Rousseau rushed forward and fired a PIAT antitank weapon at point-blank range. The round struck the Mark IV’s turret, and the turret exploded.

Smith finally caught up with Triquet after losing a Sherman to a German tank that subsequently was silenced. As they advanced, the Canadian tanks knocked out three more German tanks that were shelling Triquet’s company. The German tank crews also racked up their own kills, putting two more of Smith’s tanks out of action. But the surviving Canadian tanks knocked out three more German tanks.

“There are enemy in front of us, behind us, and on our flanks,” Triquet shouted to his men. “There is only one safe place—that is on the objective.” Triquet was down to 14 men, but it was enough to drive out the German paratroopers and capture Casa Berardi. After knocking out another German tank, Smith brought up his four remaining tanks and the small band of Canadians held onto their objective. By nightfall on December 14 the rest of the Royal 22nd Regiment arrived, strengthening Triquet’s hold on his objective. Triquet later received the Victoria Cross for his actions.

Other Canadian attacks that day made little headway. Vokes worked on another plan as it was crucial that help reach the Royal 22nd Regiment. On December 15, the Carleton and York Regiment was ordered to attempt another breakthrough of The Gully. The new attack failed.

Vokes decided on a more indirect attack on Cider. His three-stage plan was to have the 48th Highlanders attack north with the aim of cutting the Villa Grande road about 2,000 yards from Cider. The RCR was given the task of capturing Cider. After that objective was achieved, the 2nd Brigade would launch an attack designed to capture Ortona.

Operation Morning Glory, as the first phase of the attack was called, began at 8 am on December 18. Canadian artillery batteries lay down a creeping barrage that advanced 100 yards every five minutes. Twenty minutes after the opening barrage, the 48th Highlanders advanced behind the shell curtain. They were supported by Squadron B of the 12th Canadian Armoured Regiment. The advance went well and the Highlanders quickly silenced enemy resistance. By 10:30 am they had captured their objective.

Phase II: Operation Orange Blossom

Operation Orange Blossom, the second phase of Vokes’ plan, began at 11:45 am. The attack faltered immediately. While the artillery was able to register targets before Morning Glory began, the same did not hold true for Orange Blossom. Gunners had no choice but to rely on inaccurate maps, which resulted in shells landing on positions held by Canadian troops. The gunners quickly changed this by advancing the barrage 400 yards ahead of the RCR and also by laying protective fire on its right flank. The difficulty with the artillery permitted the German paratroopers to return to their guns and lay down a deadly fire on the RCR that stopped its advance.

The RCR regrouped and continued its attack the next day. With a more accurate creeping barrage beginning at 2:15 pm, two companies set out with tank support. They captured the Cider crossroads two hours later. After nine days of hard fighting, the Canadians had at last taken The Gully. On the evening of December 18, the Germans fell back to Ortona.

While the Canadians had struggled to reach Cider, the Germans had been hard at work transforming the coastal town of Ortona into a death trap. The Germans systematically blew up buildings in an effort to block the narrow cobblestone streets and to channel the attackers into the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the town’s main thoroughfare. The Corso Vittorio Emanuele led to Piazza Municipale, the town square, where the German paratroopers had placed machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns in the surrounding buildings in an effort to capture the attackers in a murderous crossfire.

At noon on December 20, the Loyal Edmontons, supported by Squadron C of the Three Rivers Regiment, advanced on Ortona following a creeping barrage. Their objective was to reach a handful of buildings at the southwestern outskirts of the town. After a sharp encounter with the enemy, they reached the objective at 2:26 pm. The Loyal Edmontons dug in and waited for a company of the Seaforth Highlanders, which was to capture a church on the edge of the town. The soldiers of Company C of the Seaforths crawled through a minefield and then scrambled up a cliff. German paratroopers hurled grenades at the Seaforths as they scrambled up the slope. During the fighting, the Canadians knocked out three machine-gun nests.

Four hundred yards away lay the church. One platoon headed for the church, while another platoon cleared out Germans from nearby huts. Enduring small arms and mortar fire, the platoon attacked the church but was driven back by an enemy counterattack. The paratroopers, in turn, were beaten back by Company C. At nightfall the Canadians were still 300 yards short of the church.

The Loyal Edmontons attacked on a two-company front the next morning. Company B advanced through cultivated fields to capture a handful of buildings on the edge of the town. The 100 soldiers of Company D advanced over open ground under machine-gun and sniper fire, which inflicted heavy casualties and forced them back. After a second attack failed, Company D was down to 17 men. Company commander Major Jim Stone divided the survivors into three groups. He wanted to follow Company B into Ortona but was ordered by his regimental commander, Lt. Col. Jim Jefferson, to continue attacking from his position because it was crucial to have troops on both sides of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele to protect the tanks.

Ortona Dubbed “Little Stalingrad”

Lieutenant John Dougan, in charge of six men in Stone’s depleted company, had the tough task of leading the attack. Spotting a narrow ditch that led to an apartment building on the edge of the town, Dougan decided to use it as his route of attack. “We’re all going to die anyway, so we might as well give it a go,” he told his men. The squad crawled up the ditch using smoke grenades for cover. They hoped the Germans did not have a machine gun at the other end.

Fortunately, the Germans did not have a machine gun posted at the other end of the ditch. Dougan and his men were followed by Stone and the remains of Company D. The men seized a large house and fired down on enemy troops in slit trenches. Sherman tanks rumbled forward, penetrating 200 yards into Ortona. They found the streets clogged with rubble from destroyed buildings and sewn with mines. The Loyal Edmontons pushed into the town and made it as far as the Piazza Vittoria by nightfall. This put them a quarter of a mile from the Piazza Municipale.

While the Loyal Edmontons battled their way into town, the Seaforths captured the church and began to advance up a street called Via Costantinopoli, in the eastern part of Ortona. They and their tank support met stiff German resistance. Outflanking the Germans was problematic because of 15-foot-high rubble piles. Brig. Gen. Bert Hoffmeister, the commander of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade, ordered the rest of the Loyal Edmontons and Seaforth companies into the town. The PPCLI was held in reserve. The bloody battle, which war correspondents dubbed “Little Stalingrad,” was under way.

With reports that the Corso Vittorio Emanuele was clear of roadblocks for 300 yards, Stone devised a bold plan to catch the Germans by surprise on December 22. His plan called for the tanks of C Squadron to drive in low gear with sirens wailing and guns firing. The infantry would go along beside the tanks.

“We started off and the noise was absolutely deafening,” Stone said afterward. “We got a hundred yards without a shot being fired at us.” The lead tank stopped 25 yards from a large rubble pile.

Knowing every minute was crucial, Stone quickly climbed up on the tank. “What the hell’s the matter?” he asked the tank commander. The commander pointed at a piece of sheet metal lying on the road ahead of him and said he thought it might be covering a mine. Stone was angry. The tank advance had ground to a halt, and his plan was unraveling.

Urban Fighting Continues Along Piazza Municipale

Suddenly, a German 57mm antitank gun opened up on the lead tank. Stone ordered a soldier to fire his antitank gun in response, but he missed. Throwing a smoke grenade at the antitank gun, Stone charged the gun and flung a grenade over the armor shield, killing the crew.

The Canadians then began fighting house-to-house toward the Piazza Municipale. In the bloody street fighting that followed, objectives were broken down to company, platoon, and section level. A strict system was set up in which commanders reported when each building had been cleared before starting on a new one. The buildings themselves were death traps with the Germans booby trapping empty ones or leaving delayed demolition charges in them. The fronts of some buildings were blown off by the Germans, leaving the interior exposed to machine-gun fire. Machineguns also covered the heaps of rubble blocking the streets.

Upon reaching the entrance of Piazza Municipale, Stone’s men found a killing zone with at least five German machine guns pouring death into the square from nearby buildings. One of these was the municipal hall. The paratroopers had removed the town clock from the tower atop the hall so that they could use it as a firing position.

Private C.G. Rattray and two other soldiers rushed into a building and cleared the ground floor. Then Rattray headed up the stairs and single-handedly took out three enemy machine guns and captured five paratroopers. With night approaching, the fighting died down. Canadian tanks withdrew from the town under cover of darkness to avoid to being attacked in the narrow streets.

The following morning the Canadian advance continued building by building. The Loyal Edmontons cleared Piazza Municipale and started toward the Aragonese castle and an adjacent cemetery. They met stiff resistance. The Seaforths were given the task of clearing the western half of the town.

With tanks finding it hard to move through heaps of rubble on the streets, the Canadians manhandled 6and 17-pounder antitank guns into Ortona. The guns proved extremely useful. The Canadians used an armor-piercing round to punch a hole in the wall of a German-held building; after that, they fired multiple rounds of high-explosive shells into the building until its occupants were dead. The guns also proved useful not only in clearing the crest of rubble piles so tanks could get over them, but also in killing German snipers on the rooftops.

To avoid exposing themselves to fire on the streets, Canadians began “mouse-holing” from one building to the next. Battalion pioneers would place a demolition charge against the intervening wall on the top floor, and while the attacking troops waited on the ground floor, the pioneers would set the charge off. The troops would then race upstairs, toss a couple of grenades through the gap, and burst into the next building with Tommy guns blazing.

Vokes’ Final Phase

While the 2nd Brigade advanced house to house to the center of Ortona, Vokes ordered the 1st Brigade to advance northeast and cut the roads running north of the embattled town to Rollo and Pescara. This would cut the German paratroopers’ supply line and trap them in Ortona.

Following a creeping barrage, two companies of the Hasty Ps supported by Shermans from Squadron A of the Ontario Tanks, pushed off at 9:30 am for their objective, a bulging ridgeline 1,000 yards north of the Tollo road. The tanks quickly bogged down in the mud, but the infantry continued on, almost reaching their objective an hour later. Then the artillery barrage lifted leaving the Canucks exposed to enemy fire. The two companies went to ground with heavy casualties. Another company was brought forward and the Hasty Ps captured the ridge. The remaining company was brought up and dug into the Hasty Ps’ tenuous position. The Hasty Ps would spend a tense night beating back paratroopers armed with automatic weapons from the 3rd Battalion of the 3rd Parachute Regiment, who tried to infiltrate their position and attack them from the rear.

With the ridgeline captured, the second phase of Vokes’s plan was launched. The 48th Highlanders quietly slogged past the Hasty Ps position single file in the rain at 4 pm, headed for their objective of high ground overlooking the small villages of San Nicola and San Tommaso. The boldness of the night attack without artillery or tank support paid off as the Highlanders surprised and captured two houses filled with Germans. They then pushed on and seized their objective at 7:40 pm.

The final phase of Vokes’ plan kicked off on the morning of December 24 with the RCR intending to pass through both the Hasty Ps and the Highlanders to capture the main highway north of Ortona. There would be no creeping barrage to cover them for fear of hitting the Highlanders. Instead, four artillery forward observation officers went with them to call down artillery strikes where needed.

But the attack did not go well in the daylight as German paratroopers were still in the area and mortar and artillery fire broke up any chance of reaching the isolated Highlanders. Major Storme Galloway, commander of the RCR, called off further daylight attacks and waited for darkness before sending a company forward to reach the Highlanders. Fierce machinegun fire drove them back. A fresh attempt would have to wait for Christmas Day.

But the attack did not go well in the daylight as German paratroopers were still in the area and mortar and artillery fire broke up any chance of reaching the isolated Highlanders. Major Storme Galloway, commander of the RCR, called off further daylight attacks and waited for darkness before sending a company forward to reach the Highlanders. Fierce machinegun fire drove them back. A fresh attempt would have to wait for Christmas Day.

Christmas Eve in Ortona saw continued street fighting and casualties mounting on both sides. The Germans received much needed reinforcements when the 2nd Battalion of the 4th Parachute Regiment reinforced the embattled 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Parachute Regiment. The two Canadian battalions, meanwhile, were receiving replacements, but with the horrific casualty rate many rifle companies were down to 30 men. Despite all this, the Canadians slowly pushed back and rooted out the paratroopers. By that point, half of the town was in Canadian hands.

“This Is Ortona, A West Canadian Town”

Fighting continued through Christmas. But for the Canadian troops in Ortona there was a break in the action as Seaforth Highlander companies were rotated back to enjoy a Christmas dinner served in the captured Church of Santa Maria di Constantinopoli. Many soldiers in the Loyal Edmontons were not as fortunate, although attempts were made to get the roast pork dinner up to them.

German paratroopers surrounded the 48th Highlanders and hammered the Canadians with mortar and artillery fire. The RCR was ordered to abandon its original plan of cutting the highway and instead establish a corridor to the 48th Highlanders. Sixty men of the Saskatoon Light Infantry started out at dusk. They made contact with the beleaguered Highlanders, giving them much needed supplies and extracting their wounded.

It was none too soon as at 10 AM on December 26, the German paratroopers launched a major counterattack. The surrounded Canadians fought desperately, throwing back a total of three German assaults. Three Sherman tanks eventually broke through and came to their aid. The 48th Highlanders were not long in striking back at the paratroopers. Their attack forced the Germans to withdraw to San Nicola and San Tommaso.

Fighting continued in Ortona with the paratroopers’ control of the town dwindling to a small section of the old quarter in front of the castle. The elite paratroopers fought fiercely using flamethrowers, machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns. On December 27, an officer in the Loyal Edmontons and 23 men were in a two-story building distributing ammo when preset explosives left behind by the Germans blew it up. Only three men survived. The Canadians quickly retaliated when their engineers set explosives under a building held by the Germans and detonated the charges, killing about 50 Germans in the blast.

Believing that one more hard push would clear the town, Hoffmeister ordered the PPCLI into the fight. Patrols sent out the morning of December 28 found that the German paratroopers were gone. They had been ordered to withdraw the night before. Ortona was in Canadian hands.

Fighting still raged northwest of Ortona where the 48th Highlanders captured San Nicola and San Tommaso on December 29. Two battalions of the 3rd Infantry Brigade were then inserted back into the fight with orders to push the paratroopers across the Riccio by early January.

December had been a bloody month for the 1st Canadian Division, costing it 2,339 casualties, of which 502 were killed. German losses are harder to determine, although they were likely heavy, particularly for the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division.

The Allies would not capture Rome for another six months. But the 1st Canadian Division owned Ortona. This was reflected by a hand-painted sign that the Edmontons and Seaforths placed in front of the battered town that read, “This is Ortona, a West Canadian Town.”

Excellent presentation of event!

Both my father (1st Medium Artillery) and Father in Law (Calgary Tanks) were at Ortona. Both said it was by far the fiercest battle of the war from their perspective. My father came home on a hospital ship and a wallet of my father in law’s is in the Stavely museum, badly burnt as he escaped a burning tank. I tell our children and grandchildren how very fortunate they are to be here. And how proud they should be of the role played by their ancestors.

Lest we forget! Proud to say I’m the nephew of James Quayle, son of Lt. Jimmy Quayle.

May the citizens of earth never forget the service these men did!! To allow us the freedom we enjoy today!

My father is 48th Highlander, even in death you’re still a 48th.

He was in Ortona and spoke of the battle with me, hell on earth was what he called it.

These “D Day Dodgers” in sunny Italy beat some of the best the Germans could field.

I’m very proud of my father and his regiment, the 48th Highlanders.

Well Trevor, the Canadians liberated the area in Belgium I live in, they were a bunch of hard men who did all volunteer.

A few years ago I met Norm Cromie, who fought in WW2 in the 48th highlander regt. A very kind man, maybe your father knows him?

I met your uncle on two occasions … he mentioned me in his book. Lovely man.