by Roy Morris, Jr.

Living in Chattanooga is a little like living inside a museum. American Civil War reminders are all around: many of us remember going as students on field trips to Point Park and Chickamauga Battlefield and spending long Sunday afternoons driving with our families along the winding, monument-strewn Crest Road on Missionary Ridge. My own father, a combat infantryman in World War II, once told my brother and me that the gray-green moss growing on the boulders of the side of Lookout Mountain was gunpowder left over from the Battle Above the Clouds. It seemed plausible to us. After all, Dad had been in a war himself.

[text_ad]

Looking at photographs of Chattanooga during the Civil War, you can recognize many of the same landmarks that are still here today. Lookout Mountain, of course, still looms over the city, and Moccasin Bend still traces its serpentine route around the base of the mountain. The Crutchfield House, now the Read House, where Jefferson Davis almost fought a duel with local unionist Thomas Crutchfield on the eve of the war, remains at the corner of Broad Street and the old Ninth Street, now renamed Martin Luther King Boulevard. Union Station is gone, but Chattanooga’s other historic railway depot, Terminal Station, was restored several years ago as the Chattanooga Choo-Choo. It’s only right that it was. Railroads, after all, were what drew the Union and Confederate armies to Chattanooga in the first place. They didn’t go there for the view.

Squarely in the Crosshairs

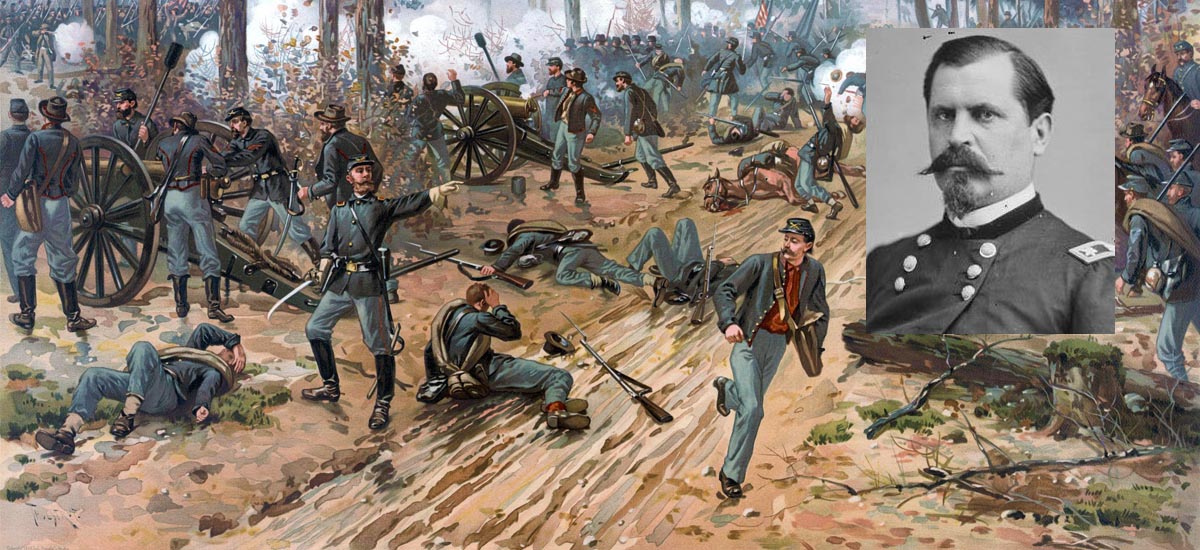

For nearly three months, from early September to late November 1863, Chattanooga was the central focus of the war. There had already been a brief shelling of the city a year earlier by Union artillery, but no concentrated efforts were made to capture the city until the late summer of 1863. Then the war arrived with a vengeance, and the little river town, which had been established only 25 years earlier as a trading post for white settlers and Cherokee Indians, found itself squarely in the crosshairs of two contending armies.

Ultimately, Chattanooga paid a huge price for its brief moment in the sun. By the time Union forces under their new commander, Ulysses S. Grant, broke the Confederate siege at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, there were scarcely any homes or trees left standing in the city. Federal troops had torn them all down for firewood during the chilly autumn nights. By then, many of Chattanooga’s pioneer citizens had left town as refugees, never to return. It is one of many ironies of the war that a number of former Union soldiers, including future mayor John T. Wilder, resettled in Chattanooga after the war. Victors’ memories are always fonder.

“Whose Side Were We On?”

A common question we asked as children growing up in Chattanooga was, “Whose side were we on?” It was a question without an easy answer. We lived in the South, but we also lived in the United States. We pledged allegiance to the Stars and Stripes, but we waved the Confederate Stars and Bars at football games. There was the Rebel Drive-in, the Dixie Theater, and Confederama, a popular tourist stop that featured a large-scale paper-maché diorama of the city during the Civil War, complete with flashing lights and tinny sound effects dramatizing cannon fire. A popular bumper sticker showed an old coot in a Confederate kepi vowing, “Forget, hell!” As the dozens of plaques and monuments scattered about our lovely little city ensure, that’s not likely to happen. We’re at 150 years and counting. Gunpowder still dusts the boulders on Lookout Mountain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments