By Jacqueline Vautrain Collins

Spring had finally arrived in the mountainous area of the Austrian Waldviertel, land of long winters and short summers. Timid clumps of grass were showing up here and there in the meadows, at one time verdant, but now barren surfaces. In the distance, light green growth softened the dark green of the dense woods of pines surrounding the camp. Inside the camp, taking advantage of the welcomed warmth, the men laid out their clothes and all kinds of articles to air and dry out the mustiness of months of winter rain and snow.

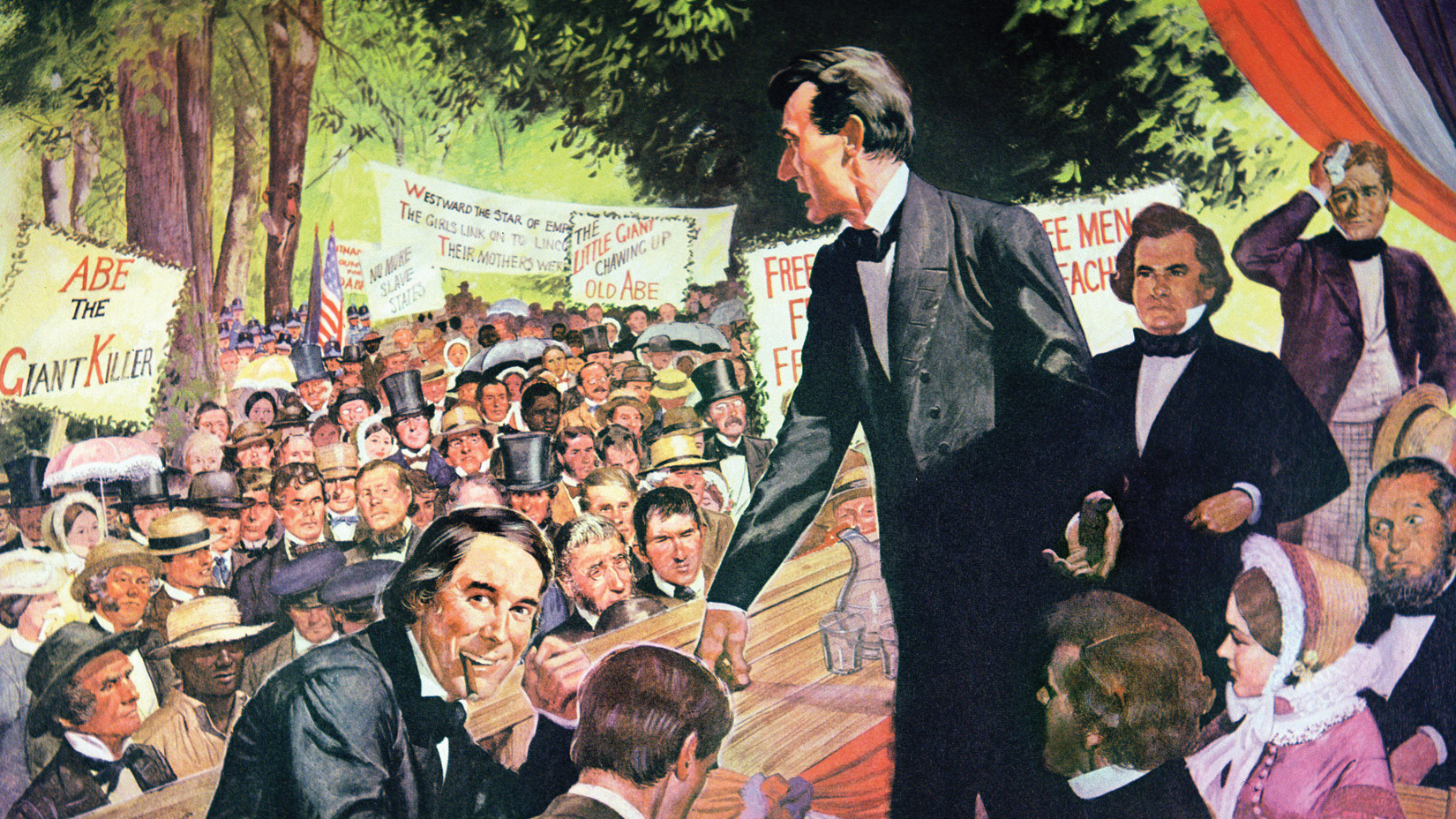

In one of the prairies behind a barracks, half a dozen men were busy with shovels and wheelbarrows moving clumps of earth around what was known as the open-air theater, in reality a gentle slope with a makeshift stage at the bottom, a place where the men could sit on the ground to watch plays, shows, and other entertainment. They were digging a trench. A few feet from the edge of the theater and parallel to the slope a double row of barbed wire stretched from one watchtower to the other. Rumor had it that the trench would serve to channel the water from the frequent downpours to prevent flooding of the hill. The men digging the trench were prisoners of war in Oflag XVIIA, one of 17 German prisoner of war (POW) camps predominantly holding French officers during World War II. Located on a remote plateau some 60 miles northwest of Vienna, close to the Czechoslovakian frontier, Oflag XVIIA housed 5,000 officers, captives since June 1940. Twenty-eight low-lying wooden barracks—each 5,400 square feet and occupied by 220 men—bordered a central alley. In the back of the barracks were the meadows. The entire complex was enclosed by a double row of barbed wire. And in the months to follow, it would provide the setting for one of the more daring POW escapes in the entire war.

As soon as they arrived, the officers organized their own command, and in the intervening three years created the feel of a small French town, adding landscaping to the barren alley, transforming a vacant spot off the alley into a central square with a gazebo, and erecting a bell tower for the barracks designated as a church. They established institutions such as a library and a university that held regular classes, entertained with a number of theater troupes and an orchestra, and formed sports teams. They clandestinely acquired 23 radios and formed a fully functioning news service, which redacted a daily communiqué to be read in each barracks every evening, keeping the prisoners abreast of the progress of the war.

Over the years, individual prisoners attempted 32 escapes using a variety of means. Some would hide in boxes in the middle of trucks leaving the camp, or under the truck, or cut the barbed wire and pass under it. Two or three men would build tunnels, starting usually under a barracks. No one succeeded in making good their escape. The Germans probed the ground around the barracks and examined their flooring most every day. Sometimes telltale signs, an imprudent remark, or occasionally a stool pigeon caused the unfortunate discoveries. Three men lost their lives.

In November 1942, following the Allied landings in North Africa, many of the prisoners and particularly the young active duty officers were anxious to join their comrades of the French Forces who had joined the Allies, armed with equipment supplied by the Americans. They agitated for planning a big escape. By 1943, the 5,000 men had coalesced into a community with such unwavering solidarity that a large escape was considered.

Choosing the Location of the Tunnel

Aware that previous tunnels originating in the barracks had been discovered, the prisoners looked for other ways to escape. After surveying the entire camp, two of the POWs, a captain who had served in an engineering regiment and an infantryman, decided that the best place was at the upper corner of the open-air theater. It was the closest area to the outside barbed wire enclosure, requiring a tunnel half the length of one originating from under a barracks. It also had the advantage of being near the only road, which opened the possibility of access to a train station. The major hazards, however, were the theater’s proximity to a watchtower and constant patrolling by guards inside the camp.

To conceal the underground activities, the prisoners needed to justify some work on the grounds. To that end, the two officers sketched out a proposal that they said would improve the open-air theater. They showed it to the ranking POW officer, who immediately approved it to be presented to the German prison administration. For that purpose, a prisoner who was a professional architect drew an elaborate plan. It included cosmetic improvements and emphasized that drainage of the water was essential to prevent the flooding of the hill. To correct the potential problem, it was proposed that a ditch should be dug around the theater.

When the German commandant noticed that the plan included building a few bridges over the ditch to facilitate access to the theater, he was impressed and said, “You thought of everything!” The Germans always believed that prisoners who were occupied with some type of project would not be thinking of escape. The commandant agreed to distribute shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows. The tools were given in the morning and taken back in the evening. One shovel and one pick, however, ended up in the hands of the prisoners for good.

Rain Delays and the Discovery of the Blower

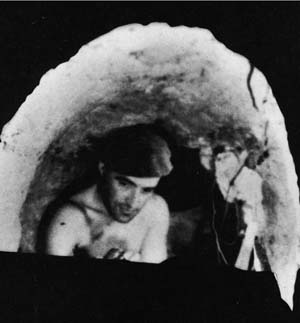

Work started on May 26, 1943, with two teams, one underground and the other above ground. It took the underground team one day to complete the entry shaft, a 60-inch hole almost 10 feet deep, mixing the excavated earth with some of the earth from the ditch. Next, they fitted a casing, which had been prepared in a barracks, and dug a storage room for handling the bagging of excavated earth. Then they were ready to begin digging the tunnel. Meanwhile, the above-ground team worked as slowly as possible digging the ditch, building mounds on both sides and a bridge over the shaft.

With the location of the shaft in plain view of a watchtower, even though covered by the bridge, the underground team had difficulty entering and leaving the tunnel without being discovered. To help hide the movements of the team, physical education classes were moved to the theater. In the morning, the exercising prisoners would do forward rolls and somersaults and group movements of attack and defense, during which the workers would disappear into the shaft, leaving the class short a few men. In the evening, with the same routine, the class would add a few more men. To guard against German patrols inside the camp, they recruited a watch team that signaled the proximity of oncoming patrols. On the ground, a large team milled around, removing earth from the ditch.

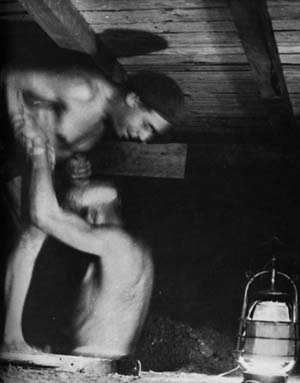

The tunnel was to be 23 inches wide and 31 inches high with a vaulted ceiling. The planned length was 276 feet. For leveling, the engineer directing the digging of the tunnel used a flashlight and his own artillery sito-goniometer, vintage 1911, which had been undetected during searches. The proper direction was obtained with a fixed plumb line in the tunnel, set behind the working face, with each team checking by sight every day.

Within days, the tunneling prisoners met a major obstacle, an eight-inch layer of kneiss rocks. When they began breaking up the rock, it made such a booming sound that they needed to find a way to drown the noise. The choir came to the rescue, its members rehearsing at the top of their voices. To light the tunnel, the diggers used tin cans filled with margarine and a tightly woven piece of cloth serving as a wick. A two-man crew worked at the end of the tunnel, one man digging while the other filled the bags, which he passed to the above-ground team. In early July, the Germans, suspicious, came with long poles to poke around the theater. They found nothing unusual.

Rain and a few raging storms delayed the work. The tunnel advanced very slowly. As summer began, it was just 40 feet long. Still, it was too long to be without ventilation. One of the POWs set out to build a machine that would serve as a blower and was almost finished when the Germans arrived at his barracks for a routine search before the watch team could send a warning. They found the blower. They did not know, however, who was building it. Nevertheless, the excavation had to stop.

The prisoner working on the blower went right back to work building a new machine. Using a dentist’s drill and tin cans, he worked out a pulley system powered by a hand crank. Set inside a wood casing mounted on two crossbars, it was capable of 1,200 turns per minute, blowing 2,825 cubic feet of air per hour. Named “Typhoon II,” it was installed by the end of July.

The prisoners resumed work on July 27, but the above-ground team, which had worked on the ditch as slowly as possible, had completed its work. The prisoners needed some plausible reason to continue working around the theater. The leader of the excavation went to the German commandant, told him that his comrades were worried about the more frequent Allied bombings, and suggested that they enlarge the ditch so that it could be used as a shelter in case of an attack. The additional excavated earth would serve as flat surfaces at the edge of the theater to be used as a solarium. The Germans agreed.

With all the delays, time was now of the essence. A date of mid-September set for the escape was the latest the prisoners could make their move before the onset of winter. To catch up, they organized an underground team of five men. Two labored at the working face. One dug while the other shoveled the excavated earth into a cart, now with wheels moving on tracks. When the cart was full, he signaled to a comrade at the entrance to pull the cart. This third worker emptied its content into bags, signaled to his comrades at the end of the tunnel to pull the empty cart back, and then passed the bags to the above-ground team. Two other men activated the blower, a particularly excruciating task. The teams were regularly replaced.

The excavation began moving at a good pace. The above-ground team mixed the earth from below with the earth of the enlarged trench and spread it and packed it down to create what looked like flat couches for the so-called solarium. The entire enterprise was supported by many other prisoners in the camp. The tailors sewed all kinds of civilian clothes. At least one man was disguised as a woman. Some compasses had been hidden in packages, and others were made in the camp. They made false identity papers, taking pictures with a clandestine camera. They copied maps, train schedules, and permits obtained from young Frenchmen who had been forced to work in Germany. They also provided the would-be escapees with German money.

On September 14, the underground team found a note from the engineer, who had inspected the tunnel the previous evening, informing them that the tunnel had reached its planned length and instructing the team to build the exit shaft. The team broke through the ground and installed a trap, which would be lifted when the first wave of escapees departed and replaced for the second wave and a potential third wave. After 31/2 months of hard work, the men at the exit portal looked up at a pure blue sky, a free strip of grass about 65 feet beyond the barbed wire enclosure, and the open road about six feet away. The tunnel ended exactly where it had been planned.

Two hundred men had signed up to leave. The selection of who would escape and in what order was rigorously handled. The men who had directly worked on building the tunnel were selected for the first wave. The order in which they left was decided by drawing lots. The second wave included those who had supported the whole effort or had made previous attempts to escape.

Finally, a possible third wave was for those who had contributed marginally to the effort. Those who escaped had stringent instructions to follow a specific itinerary and in case of capture to be silent for at least 24 hours. The first escape wave of was set for the following Saturday. Sunday’s roll calls were more relaxed, as many guards were allowed to go to Vienna for the weekend. With a new moon, Saturday night would be extremely dark.

The logistics of the entry into the tunnel required an intricate choreography. The theater was in plain view of the watchtower, and the access to the prairies, strictly prohibited after 6 pm, was enforced by beams of searchlights. The leaders of the escape again enlisted the help of the physical education trainers, who in the morning performed aerobic exercises that made use of blankets or the big capes of prisoners belonging to alpine regiments, spreading these out on the ground. By planning precise movements, rolling over or somersaulting with the blankets or capes, all the backpacks disappeared into the shaft. They were then lined up in the order of the escapees’ numbers.

Diversions Above-Ground

The prisoners devised an intricate stratagem for the entrance of the men into the tunnel. As a diversion, they scheduled some competitions in the stadium, far from the theater. Starting at noon, small groups of three or four walkers began crisscrossing from all directions. When they reached the theater, they engaged in an animated discussion with three other men sitting at the edge of the ditch near the shaft, forming a group that provided a screen for one man to disappear into the shaft. Once in the tunnel, the men lay down on their backs with their bags on their chests and with the next man’s head on their stomachs. It was a long wait, from afternoon to after nightfall. It proved to be too arduous for two of the men, who fainted despite the full force of the blower. They had to be evacuated.

At 8:30 pm, the officer in the lead, the prisoner who had directed the excavation, pushed the trap up and hoisted himself onto the side of the road. Behind him the searchlights crisscrossed fully on the barbed wire, creating the impression of broad daylight. By 9:30 pm, only a single escapee remained in the tunnel. The engineer stayed behind to place the trap back over the hole and lead the next batch of escapees the following day. With no roll calls on Sunday and no one caught so far, the German administration did not suspect anything. Saturday’s procedure was repeated on Sunday. Altogether, 131 men escaped.

Foiling the Roll-Call

The next morning, roll call took place in the barracks. The men had devised a system for some to be counted twice, using traps in the ceiling. The roll call came out exactly right. By mid-morning, however, a call from the Viennese police alerted the camp commandant that they had picked up a few prisoners. Another roll call was held. In the new count, 42 men were missing. After an extended search, the entry shaft was located by midafternoon. Then, a rigorous, painstaking roll call by numbers, checking each prisoner’s tag, showed that 120 men had disappeared. The Germans were so incredulous that they thought it was a joke and asked the prisoners to come out of hiding.

However, as more prisoners were brought back to the camp, the Germans had to admit that a large number of POWs had escaped. Most were picked up within days. A rumor had spread that a paratrooper unit had landed, sending the local police, military units, Gestapo, and the local population on the hunt. The nearby borders with Hungary and Czechoslovakia were closed.

Benefiting from being the first large escape and with the German high command anxious to conceal it as much as possible, the escapees were brought back to the camp and subjected to only some minor retaliation. Two were killed during their recapture. Eleven reached Hungary, where they were put under house arrest in Budapest. Over time, they escaped to join the resistance groups in Slovakia and Yugoslavia and some French partisans. One of them went through Turkey to North Africa and joined the French Army, which landed in southern France in August 1944. He was killed during the liberation of Alsace, fighting with the French First Army led by General Jean De Lattre de Tassigny. One escapee reached France some months later.

The escapees told many stories of their adventures, but the most colorful was the odyssey of a young lieutenant, who had created the role of an ingénue on the stage of the theater. His getaway clothes were a gorgeous lady’s outfit. He walked for about nine miles, changed his clothes, and was able to quietly take a seat in a train departing for Vienna. Unfortunately, a young woman accompanied by her beau on leave from the Wehrmacht took a seat across from him. The soldier immediately showed great interest in the disguised POW officer, who tried to be ignored. When the train arrived at the station in Vienna, everyone stood up to get off. A sudden jolt thrust the disguised POW into the real young woman, who exclaimed, “They are made of cardboard! Her breasts!”

Shoving people aside, the POW leaped onto the platform and managed to get out of the station, but running was in vain. He wound up in the station of the security forces, where for hours and still in the same outfit he endured interrogation by the Gestapo. A few days later on a train from Vienna, passengers saw a charming young woman flanked by guards, her cheeks bristling with the beard of a tramp.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments