By William F. Floyd, Jr.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had a glaring flaw. Although the Mississippi-born general had a son and daughter from his marriage to Caroline Godbold, he committed adultery on multiple occasions. “Let the women alone until after the war is over,” a Southern woman warned him. “I cannot do that for it is all I am fighting for,” he replied. The Southern cavalier was an amateur poet, an incorrigible romantic, and considered one of finest horsemen in the prewar U.S. Army.

Earl Van Dorn was born near Port Gibson, Mississippi, on September 17, 1820. He was the son of Peter A. Van Dorn, who served as a judge in the Claiborne County Probate Court. Van Dorn had the good fortune to be a great nephew of U.S. President Andrew Jackson. Jackson assisted the young Van Dorn in his quest to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Van Dorn, who graduated number 52 in the class of 1842, was only four rungs from the bottom of his class. During his troubled education at West Point, he was nearly dismissed for excessive demerits.

After his graduation, brevet Second Lieutenant Van Dorn served in the 7th U.S. Infantry stationed at Fort Pike, Louisiana. While serving at the federal arsenal at Fort Morgan, Alabama, he wed Godbold in 1843. He eventually was transferred with his regiment to the star-shaped Fort Texas on the north bank of the Rio Grande in what is now Brownsville, Texas. The fort was situated in contested territory that the Mexicans claimed belonged to them. He was one of the soldiers who defended the fort against an attack in May 1846 by General Mariano Arista’s Mexican Army.

He tramped with General Zachary Taylor’s army into northern Mexico in September 1846 and fought with the victorious American forces in the Battle of Monterey. The 7th U.S. Infantry was transferred to General Winfield Scott’s army for the pending expedition to the Mexican Gulf port of Veracruz in early 1847. Having received a promotion to first lieutenant, Van Dorn served as an aide-de-camp on the staff of General Persifor F. Smith, who commanded the 1st Brigade of the 2nd Division in Scott’s army. He would be in the thick of the fighting as the moved war into the Valley of Mexico.

Although he had been an unruly student, he appeared to be establishing himself as a fine soldier. He was brevetted captain for gallantry at Cerro Gordo, and again brevetted major for his bravery at Contreras and Churubusco. “No young officer came out of the Mexican War with a more enviable reputation, earning commendations for his actions at Fort Texas, Cerro Gordo, and Mexico City,” wrote Maj. Gen. Dabney H. Maury of Van Dorn’s performance during the war.

Following the war, he was transferred to various posts, winding up at one point fighting in the Third Seminole War. In March 1855, Van Dorn was promoted to captain in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and sent to serve with his unit on the Western frontier. His company was sent to Camp Cooper, Texas, which was situated on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River about 40 miles north of present-day Abilene.

In autumn 1858, Brevet Major Van Dorn led a strike by four companies of U.S. Cavalry against a Comanche village on the Washita River in Indian Territory. The cavalrymen rode north on September 30. Although they had Indian guides, they failed to reach their objective that day. On October 1, they approached the Comanche camp shortly after sunrise. The engagement became known afterward as the Battle of Wichita Village. He divided his troops into four columns and ordered the men to approach with stealth, riding in pairs with 100 yards separating each pair. When the cavalry struck the camp, the Indians organized a hasty defense. Although they were taking heavy casualties, the Comanches fought with great frenzy to protect their women and children. Eventually, the Indians withdrew. The cavalry burned the camp to the ground and rounded up 300 horses.

Late in the battle, Van Dorn engaged two Indians riding double on a horse in an effort to escape. He shot and killed their horse, but they fired on him with their bows from a kneeling position. He was struck in the wrist by an arrow that ran up through his forearm. The second was a near fatal wound that struck him in the ribs. He was so badly hurt that some of the soldiers remained at the site with him for five days and on the sixth day dragged him out on a litter. He was sent home to Mississippi where he convalesced for five weeks. “I had faced death often, but never so palpably before,” he wrote.

Van Dorn withdrew his commission from the U.S. Army on January 31, 1861. At the outset of the war, he commanded Mississippi troops. On March 16, 1861, he received a commission as a colonel in the Confederate army. He was immediately given command of the garrisons of the two forts below New Orleans on the Mississippi River. The following month, he was entrusted with the Department of Texas where he directed forces in capturing and securing various resources of the U.S. Army. For example, he supervised the capture of the Star of the West in Galveston Harbor on April 20.

The Confederate high command thought well enough of Van Dorn to order him to report for duty in Richmond, Virginia. He arrived in the capital of the Confederacy in September. In October, he was given command of the First Di vision in General Joseph Johnston’s short- lived Army of the Potomac, which eventually became the Army of Northern Virginia. Johnston commanded the division for slightly more than three months during a period of inactivity as the Federals contemplated their next step following the disaster at First Bull Run.

In mid-January 1862, Johnston was reassigned to the Trans-Mississippi Department. He took command of the department at a point in which the Confederates had withdrawn to Arkansas following their defeat at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. It fell to Van Dorn when he arrived to settle an ongoing dispute between rival Maj. Gen. Sterling Price and Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch, who commanded the Missouri State Guard and Army of the West, respectively. The two had clashed repeatedly over who should direct the forces, but when Van Dorn arrived he outranked both. It was an important occasion for Van Dorn because it marked the first time he would lead a Confederate army on a campaign.

Van Dorn’s first objective was to drive the army of Union Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis out of northwestern Arkansas. On March 4, Van Dorn’s 17,000-strong army advanced toward Curtis’s 10,500-man Army of the Southwest deployed on the high ground overlooking Little Sugar Creek. The two sides made contact two days later when the Confederate army attacked the Federal rear guard. Van Dorn had the misfortune of falling seriously ill during the battle. For that reason, he was forced to ride in an ambulance and issue orders from it.

Under cover of darkness on the night of March 6, Van Dorn split his army into two columns for a forced march to outflank the Union position on the bluffs along Little Sugar Creek. The Confederate plan called for McCulloch and Brig. Gen. Albert Pike to engage the Union right and center, while Price attacked the Union left at Elkhorn Tavern.

Price’s attack was slow in developing. His troops did not attack until late morning. The Federals repulsed two Confederate charges. The third charge, delivered with the full fury of Price’s column, drove the Union forces south past the tavern. At the opposite end of the line, the Confederates broke through the Union line but were soon pushed back.

On the morning of March 8, Curtis correctly surmised that the Confederates were running low on ammunition. He ordered two Union divisions at Elkhorn Tavern to launch a counterattack. The Federals forced back the Confederate left, which prompted Van Dorn to order a general retreat.

The Battle of Pea Ridge showed the danger of a cooperative attack. If Van Dorn had struck the Union rear with the force of his entire army, it was possible he would have achieved victory. A lack of coordination among Confederate units cobbled together from several commands contributed substantially to the Confederate defeat.

The loss of huge swaths of territory in Kentucky and Tennessee to the Union Army in the wake of the Confederate defeat at Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, created a crisis situation for the Confederacy. As a result, Van Dorn received orders to march his army from Arkansas to Mississippi. Van Dorn’s troops arrived in Corinth on April 23, and he reported to his superior, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the commander of the Army of Mississippi.

For obvious reasons, Van Dorn was anxious to restore his reputation, which had been badly damaged at Pea Ridge. As the Federals under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans advanced on Corinth, Beauregard ordered Van Dorn to hold the Confederate line east of the city. In the monthlong siege, which lasted from April 29 to May 30, Van Dorn received orders to attack Maj. Gen. John Pope’s army at Farmington, Mississippi, which lay seven miles east of Corinth. Two attempts to engage Pope failed when he withdrew. On Van Dorn’s third attempt against Pope on May 22, the general got lost. Van Dorn’s attack that day was intended as the first step in a major Confederate counterattack, but when Van Dorn failed to execute his attack properly, Beauregard called off the entire counterattack.

Van Dorn was still eager to restore his reputation, which plummeted even farther downward after the debacle in the First Battle of Corinth. On June 28, he was appointed to command the Department of Southern Mississippi and East Louisiana. At the time, Union riverine forces were converging on Vicksburg from above and below the city. He rushed to Vicksburg to direct the defenses, seeking to keep control of a three-mile stretch of the river directly under the Confederate guns on the Vicksburg bluffs.

Van Dorn arrived in Vicksburg and set about raising the morale of the city’s 4,000 garrison troops and improving the Confederate defenses. He strengthened artillery positions, ordered the construction of new fieldworks, and established strong cavalry patrols to guard the approaches to the city. The arrival of Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge’s 5,000-man division greatly strengthened the garrison. But just when everything seemed to be looking up for him, he made the

mistake of declaring martial law in some of the Mississippi counties and Lousiana parishes. Confederate citizens protested, and this brought the wrath of Richmond upon him. In October 1862, Van Dorn was replacednas department commander by Lt. Gen. John Pemberton.

Still in search of a way to redeem himself as an army commander, Van Dorn set his sights on Corinth, which was occupied by Rosecrans’s Army of the Mississippi. Van Dorn led his Amy of West Tennessee against Corinth in early October. In the two-day Second Battle of Corinth, which was fought October 3-4, the Confederates repeatedly made frontal assaults against strong Union fieldworks. On the first day, the Confederates made considerable progress. The Rebels carried some of the outer works, which forced the Yankees to fall back to their inner fortifications. The Confederates attacked these tough positions by assaulting them in small groups. But the Confederates exhausted them- selves in the hard fighting.

During the night Van Dorn issued orders for a fresh assault in the morning. Both sides fought desperately to maintain their positions. At one point, the Confederates penetrated to the streets of Corinth, but the Federals counterattacked and drove them out. The Confederates launched a heavy assault on Battery Robinette, west of Corinth. Here the Confederates desperately tried to overwhelm the Federals holding a key artillery position. The troops fought hand to hand with bayonets, clubbed muskets, and fists. Despite the desperate fighting, Van Dorn ultimately ordered a retreat. Some of the officers who served under Van Dorn during the battle blamed him for the defeat. One of them, Brig. Gen. John Bowen, brought charges against Van Dorn, but a court of inquiry dismissed them.

On December 12, 1862, Pemberton assigned Van Dorn to serve as his cavalry commander. Five days later, Van Dorn embarked on a cavalry raid against the Union depot at Holly Springs, Mississippi. Van Dorn’s raiders destroyed a number of large caches of Union supplies and also disrupted the Federal overland advance against Vicksburg. The Holly Springs Raid was one of the great cavalry raids of the Civil War, and it proved beyond a doubt that Van Dorn was suited for cavalry command.

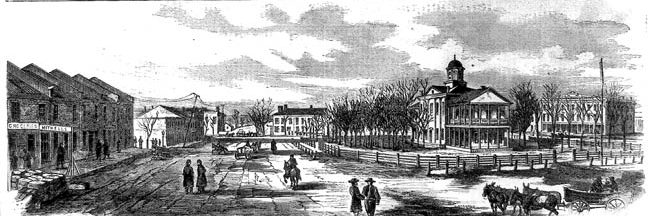

In early 1863, Van Dorn and his cavalry command were transferred to Middle Tennessee. Van Dorn established his headquarters at Spring Hill. His job was to protect the left flank of Bragg’s Army of the Tennessee and operate against the Federal line of communications stretching north to Nashville. The Federal forces in the area were surprised at Van Dorn’s constant attacks and repeatedly sallied forth from their strongholds in captured towns in an attempt to bring him to bay.

At Thompson’s Station on March 5, Van Dorn defeated Union Colonel John Coburn’s 2,800 troops. On March 25, Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who served under Van Dorn at the time, smashed a Union column at Brentwood, Tennessee, capturing men and matérial. Out of this affair came a heated altercation between Van Dorn and Forrest. At one point, the two hotheads drew their swords against each other.

Van Dorn’s demise began shortly after his arrival in Spring Hill, when he met Mrs. Jessie McKissack Peters. Mrs. Peters was the much younger third wife of a wealthy landowner and retired doctor, George Peters. While her husband was away at the Tennessee State Legislature, his wife could be seen at Van Dorn’s headquarters, which left little doubt about the nature of her visits. These unsupervised visits and their carriage rides were soon the talk of the town.

It did not take long before Peters became aware of what was occurring. He was determined to catch Van Dorn in the act. The doctor left on one of his routine trips, but he doubled back in an effort to observe his wife and her lover. On the morning of May 7, 1863, Peters arrived at Van Dorn’s headquarters.

“I came upon the creature at about 2:30 AM, where I expected to find him,” Peters told the Nashville police. Peters said that Van Dorn begged for his life. A number of officers noticed Peter’s arrival at the general’s headquarters but thought nothing of it. The officers would later find Van Dorn slumped over his writing desk, a bullet in the back of his head. Peters was never prosecuted for the crime.

A great deal of mystery surrounded the murder of Van Dorn. Peters contended that Van Dorn had violated the sanctity of his marriage; however, there were others who said that the doctor had political reasons involving his support of the Federal forces in Tennessee. The mystery was further compounded by conflicting reports concerning the circumstances of Van Dorn’s murder and the activities of the doctor and his wife after the murder. The couple soon divorced but later reunited in Arkansas where Peters had mysteriously received a land grant. Van Dorn’s sister, in her personal memoir published in 1902, offered a strong argument that the doctor had more sinister reasons. She asserted that Peters was disloyal to the Confederate cause he had originally supported.

Despite Van Dorn’s personal failings and his repeated poor performances as an army commander at the Battle of Pea Ridge and the two battles at Corinth in 1862, after the war he would be regarded as one of the South’s top cavalry commanders. It was a fitting epitaph for a U.S. Army soldier who almost died from a Comanche arrow.

Article says newly commissioned Lt Van Dorn began service with the “7th US Cavalry” before the Mexican War. Except there was no such unit, until post ACW.

6th Cavalry wasn’t formed til 1860.

Who writes this stuff?

Thanks for the correction. Lt. Van Dorn was assigned to the 7th US INFANTRY and later transferred to the 2nd US Cavalry. You’ll find the byline at the top of the story.